A comprehensive guide to L1 regularization (LASSO) in machine learning, covering mathematical foundations, optimization theory, practical implementation, and real-world applications. Learn how LASSO performs automatic feature selection through sparsity.

This article is part of the free-to-read Machine Learning from Scratch

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

L1 Regularization (LASSO)

Regularization in Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) is a technique used to prevent overfitting by adding a penalty term to the loss function. In standard MLR, the model tries to minimize the sum of squared errors between the predicted and actual values. However, when the model is too complex or when there are many correlated features, it can fit the training data too closely, capturing noise rather than the underlying pattern.

Regularization addresses this by adding a penalty for large coefficient values, effectively constraining the model. This encourages simpler models that generalize better to new data. Common types include LASSO (L1) and Ridge (L2), which differ in how they penalize coefficients. We cover Ridge in the next section.

LASSO, or Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator, is known as L1 regularization because it adds a penalty proportional to the L1 norm of the coefficients (the sum of their absolute values).

In simple terms, LASSO helps a regression model avoid overfitting by keeping coefficients small and can drive some to zero, which means the model ignores those features. This helps the model focus on the most useful information and makes it simpler and easier to interpret.

Advantages

L1 regularization (LASSO) offers several advantages. One of its main strengths is that it can automatically perform feature selection by shrinking some coefficients to zero. This means the model becomes simpler and more interpretable, as it focuses on the most important features. L1 regularization is also effective at preventing overfitting, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data where the number of features may be large compared to the number of observations. By encouraging sparsity, LASSO helps create models that typically generalize better to new data.

Unless noted otherwise, the intercept is not penalized, and it is good practice to standardize features so the penalty treats them comparably.

Disadvantages

However, L1 regularization also has some drawbacks. When features are highly correlated, LASSO may arbitrarily select one feature and ignore the others, which can make the model unstable and less reliable for interpretation. Additionally, if all features are actually important for predicting the target, L1 regularization might shrink some useful coefficients to zero, potentially reducing the model's predictive performance.

Unlike ordinary least squares or ridge regression, LASSO does not have a simple closed-form solution and requires iterative optimization, which can be computationally more intensive. The effectiveness of L1 regularization depends on the choice of the regularization parameter (), which should be carefully tuned to achieve good results.

Formula

LASSO regularization is formulated as a minimization optimization problem. The goal is to find the set of coefficients that not only fit the data well (by minimizing the sum of squared errors), but also keep the model simple by penalizing large coefficients. In other words, LASSO seeks to minimize a loss function that combines the usual error term with an additional penalty based on the absolute values of the coefficients. The formula for this optimization problem is:

where:

- : regularization parameter (controls the strength of the penalty)

- : number of features in the model

- : coefficient for the -th feature (where )

- : absolute value of the -th coefficient (ensures non-negative penalty)

- : sum of squared errors between predicted and actual values

The regularization parameter controls the strength of the regularization. A larger results in more shrinkage of the coefficients, and a smaller results in less shrinkage.

Written as a minimization problem, it is:

This is read as: "minimize the sum of squared errors plus the regularization penalty, with respect to the coefficients". The fully written-out formula is:

where:

- : number of observations in the dataset

- : actual target value for observation

- : intercept term (typically not penalized)

- : value of feature for observation

- : regularization parameter

- : number of features

The left side of the equations, the sum of squared errors (SSE), should look familiar from the previous section on ordinary least squares (OLS). The right side is the regularization penalty. However, unlike OLS, LASSO requires us to minimize the SSE plus the regularization penalty. OLS allows us to directly compute the optimal coefficients using a closed-form solution and vector algebra, but LASSO does not have this property.

This means we need to use optimization techniques to find the best coefficients, rather than relying on a simple formula. In other words, we are using iterative optimization methods to find the coefficients that minimize the combined objective function.

We're about to dive deep and cover several important concepts at once, including partial derivatives, the chain rule, and function minimization. While this may seem like a lot to take in, mastering these ideas here will make understanding future topics much easier. I've taken the time to explain everything in detail to help you build a strong, intuitive understanding. Take as much time as you need to understand this section. It'll be worth it.

Math and Optimality Conditions

Let's look at how LASSO finds the optimal coefficients, starting with the optimization process. LASSO solves the following optimization problem, here defined in summation form:

To find the minimum, we set the partial derivatives (where they exist) to zero. The absolute value term is not differentiable at , so we use subgradients there. We'll use the chain rule for the differentiable part. The main reason why there is no closed-form solution for LASSO is because the absolute value term is not differentiable at .

For : The partial derivative with respect to is:

Step 1: Differentiate the SSE term

The first term is the SSE. When we take the partial derivative with respect to , we use the chain rule:

Step 2: Differentiate the inner expression

The derivative of the inner expression with respect to is:

This is because:

- and are constants with respect to (derivative = 0)

- becomes when differentiated with respect to (all other terms become 0)

Step 3: Differentiate the penalty term

Let's solve for the partial derivative step by step when . Start with what we need to differentiate:

Apply the constant multiple rule

Since is a constant, we can pull it out:

Focus on the relevant term. When taking the derivative with respect to , only the -th term in the sum matters:

Handle the absolute value. When , we have (the absolute value doesn't change positive numbers):

Take the derivative

The derivative of with respect to itself is 1:

Final result for :

For : The partial derivative becomes:

We have when , so:

This gives us the negative sign in front of in the final equation.

Step 4: Combine the results

Putting it all together:

Step 5: Simplify

At , the derivative of is not defined, but its subgradient is the interval . The optimality condition becomes:

- The first term, , is the gradient of the sum of squared errors (SSE) with respect to . This measures how much the loss would decrease (or increase) if we changed a little bit.

- The second term, , comes from the L1 penalty. Here, is not a regular derivative, but a subgradient of the absolute value function at zero.

What is a subgradient?

For most values of , the derivative of is either (if ) or (if ). However, at , the absolute value function has a "kink" and is not differentiable there. In this case, instead of a single derivative, we use the concept of a subgradient, which is any value between and . That is, when , can be any number in the interval .

Why does this matter for LASSO?

This subgradient condition is what allows LASSO to set coefficients exactly to zero. If the (unpenalized) gradient, the first term above, is not large enough in magnitude to "overcome" the regularization strength , then the optimal solution is to set . In this case, the equation can still be satisfied by choosing an appropriate in .

In other words:

- If the data "wants" to pull away from zero (the gradient is large), but not enough to overcome the penalty, then the best solution is to keep .

- If the gradient is strong enough (in magnitude) to overcome , then will be nonzero, and the solution will be found where the gradient and penalty exactly balance.

This is the mathematical reason why LASSO can produce sparse solutions: the subgradient at zero allows the optimality condition to be satisfied with for some features, effectively removing them from the model.

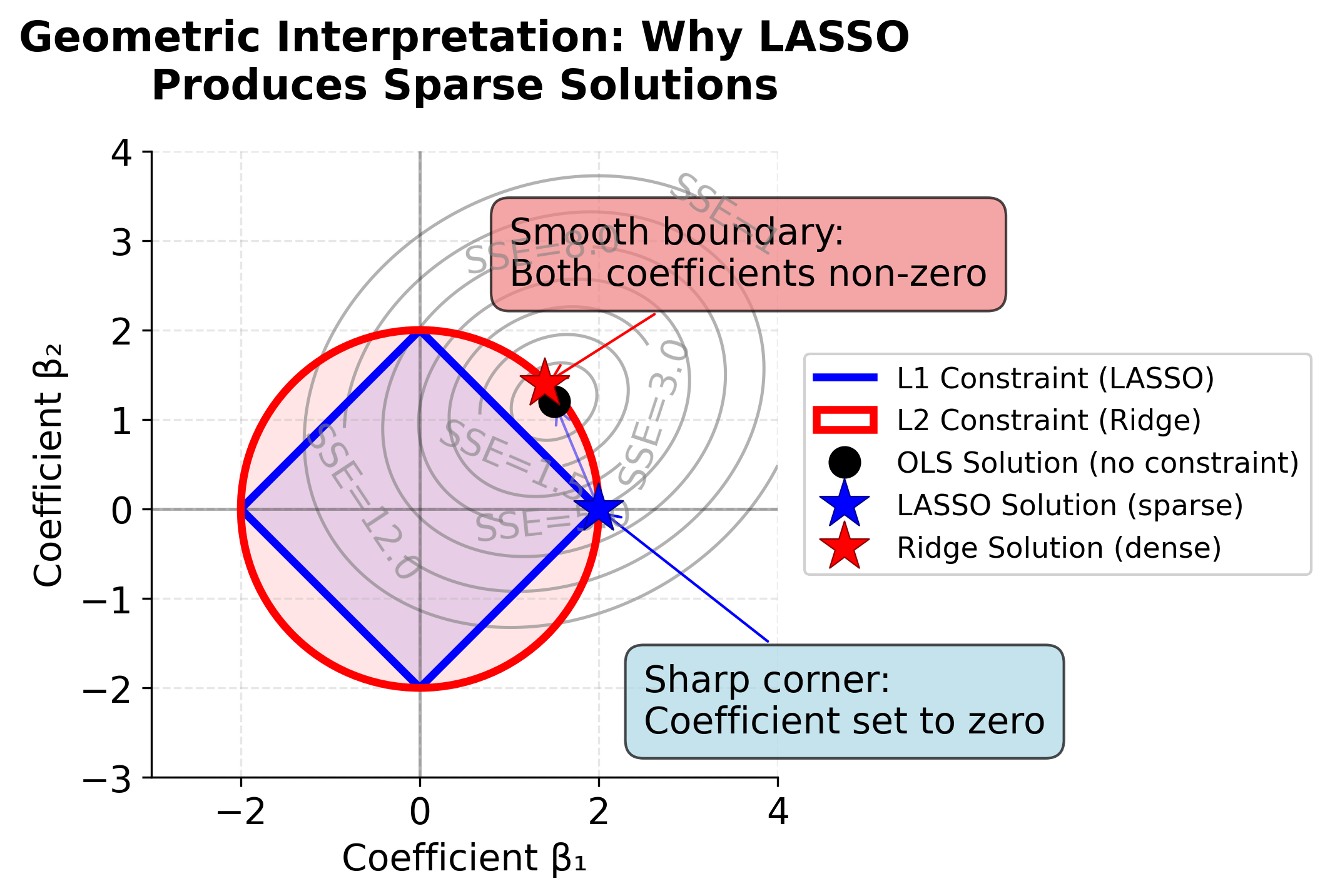

Geometric Interpretation: Why LASSO Produces Sparse Solutions

To understand why LASSO sets coefficients exactly to zero while Ridge regression does not, we can visualize the geometry of the optimization problem. The following plot shows how the constraint regions differ between L1 (LASSO) and L2 (Ridge) regularization.

The key insight from this visualization is that the L1 constraint region (diamond) has sharp corners at the coordinate axes. When the SSE contours expand outward from the OLS solution, they are much more likely to first touch the constraint region at one of these corners, where at least one coefficient is exactly zero. This is why LASSO naturally performs feature selection.

In contrast, the L2 constraint region (circle) is smooth everywhere, so the SSE contours typically touch it at a point where both coefficients are non-zero. Ridge regression therefore shrinks coefficients toward zero but rarely sets them exactly to zero.

This geometric property holds in higher dimensions as well: the L1 constraint in p-dimensional space has 2p corners on the coordinate axes, giving LASSO many opportunities to set coefficients to zero. The L2 constraint, being a hypersphere, remains smooth in all dimensions.

Matrix Notation

We can rewrite the LASSO optimization problem in matrix notation, which provides a more compact and mathematically elegant representation. This notation is particularly useful for understanding the relationship between LASSO and other optimization problems, and it's the form commonly used in machine learning libraries like scikit-learn.

From Summation to Matrix Form

Let's start with our familiar summation form and transform it step by step:

Step 1: Define the matrices and vectors

First, let's define our data in matrix form:

- : An vector containing all target values:

- : An matrix containing all features (including a column of ones for the intercept):

- : A vector containing all coefficients (including intercept):

Step 2: Express predictions in matrix form

The predicted values for all observations can be written as:

This single matrix multiplication computes all predictions simultaneously. Row of multiplied by gives:

This is exactly the prediction for observation :

Step 3: Express residuals in matrix form

The residuals (errors) for all observations are:

Step 4: Express the sum of squared errors in matrix form

The sum of squared errors becomes:

Let's verify this step by step:

Since , we have , thus:

Step 5: Express the L1 penalty in matrix form

The L1 penalty term can be written using the L1 norm:

where is the L1 norm of the coefficient vector. This means that the L1 penalty is the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients, or otherwise known as the "Manhattan distance" between the coefficients and the origin. It is the same as summing up all the features:

Final matrix form:

What we have now is a compact way of writing the LASSO optimization problem using matrix notation.

The Scikit-learn Formulation

Scikit-learn uses a slightly different but equivalent formulation that includes a normalization factor:

where:

- : regularization parameter in scikit-learn, related to traditional by

- : number of observations in the dataset

- : squared L2 (Euclidean) norm of residuals, equivalent to (the SSE)

- : L1 (Manhattan) norm of coefficients, equal to (sum of absolute values, intercept not penalized)

The expression uses the L2 norm (also called the Euclidean norm):

where:

- : L2 norm of the residual vector (Euclidean distance)

- : actual target value for observation

- : predicted value for observation , equal to

- : number of observations

When we square the L2 norm, we get:

This is exactly our sum of squared errors (SSE)! The L2 norm squared gives us the same quantity as our matrix form . The L2 or Euclidean norm is simply the square root of the sum of the squares of the elements of the vector.

We use the L2 norm notation because it is mathematically equivalent to the matrix form , but more concise and widely recognized. The L2 norm is standard in optimization and statistics, making formulas easier to read and interpret. This notation also highlights the connection to Euclidean distance, which helps build intuition about how the loss function measures the overall error.

We now got the left side of the equation, let's look at the right side. The expression is the L1 norm of the coefficient vector:

where:

- : L1 norm (Manhattan distance) of the coefficient vector

- : absolute value of the -th coefficient

- : number of features (excluding intercept)

This is exactly our L1 penalty term! The L1 norm is simply the sum of the absolute values of the elements of the vector.

Note: The intercept is typically not included in the L1 penalty, so the sum runs from to , not from to .

We know that the L1 norm offers several important advantages: it encourages sparsity by driving some coefficients exactly to zero, which enables automatic feature selection. Further, it has a clear geometric interpretation: it measures the "Manhattan distance" (the sum of absolute values) from the origin in coefficient space, and is a convex function, which ensures that the optimization problem remains tractable and that efficient algorithms can find a global minimum.

The Normalization Factor:

Let's take a closer look at the normalization factor that appears in front of the L2 norm in the scikit-learn formulation. In scikit-learn, the regularization strength is controlled by the parameter alpha (), which is related to the traditional parameter by .

This means that the scikit-learn objective function is normalized by both the number of samples and a factor of 2, making the loss function consistent with the mean squared error and simplifying gradient calculations.

This formulation is sometimes referred to as the "normalized" or "scaled" LASSO objective, and is the standard approach used in most modern machine learning libraries.

The factor serves several important purposes:

-

Sample size normalization: Dividing by makes the loss function independent of sample size. Without this, larger datasets would have larger loss values simply because they have more observations.

-

Gradient scaling: The factor simplifies the gradient calculation. Let's take the derivative of with respect to . To see how we arrive at this gradient, let's rewrite the squared L2 norm and take the derivative step by step:

Let's see how we can rewrite the term in a more manageable form. The term is a quadratic form that represents the sum of squared errors in matrix notation. To make it easier to take derivatives and understand the structure, we can rewrite it using the distributive property of matrix multiplication:

Notice that is a scalar and is equal to its transpose , so the two middle terms combine to . The last term, , can be rewritten as . Putting it all together, we get:

Taking the derivative with respect to :

- The derivative of with respect to is 0 (since it does not depend on )

- The derivative of with respect to is

- The derivative of with respect to is

So, the derivative is:

where:

- : transpose of the feature matrix

- : target vector

- : coefficient vector

Including the factor:

Or, equivalently (by factoring out the negative sign):

where:

- : normalization factor (average over all observations)

- : gradient of the squared error term with respect to

The gradient points in the direction of steepest ascent of the loss function. In gradient descent for minimization, we move in the opposite direction by subtracting this gradient from the current . Without the factor, we would have an extra factor of 2 in the gradient.

-

Consistency with statistical literature: This normalization makes the objective function consistent with the mean squared error (MSE), since is exactly the MSE.

The Regularization Parameter:

In scikit-learn, the regularization parameter is called alpha () instead of lambda (). The relationship between the two formulations is:

where:

- : scikit-learn regularization parameter

- : traditional LASSO regularization parameter

- : number of observations in the dataset

This means:

- Small : Less regularization, coefficients closer to OLS solution

- Large : More regularization, more coefficients driven to zero

Complete Mathematical Breakdown

Let's put it all together with a concrete example. Suppose we have:

- observations

- features (plus intercept)

The scikit-learn objective function becomes:

where:

- : normalization factor ( where )

- : regularization parameter

- : squared L2 norm of residuals

- : L1 norm of coefficients

Expanding this:

where:

- : index over observations

- : index over features

- : actual target value for observation

- : predicted value for observation

- : coefficient for feature

This is equivalent to:

where:

- : intercept term (not penalized)

- : value of feature for observation

- : absolute value of coefficient

Why This Formulation Matters

Matrix notation has several important practical benefits. First, matrix operations are highly optimized in modern numerical libraries, making computations much more efficient. Second, expressing the objective in terms of norms directly connects LASSO to the broader field of convex optimization, providing a solid theoretical foundation. Third, this standardized form is what most machine learning libraries, such as scikit-learn, use in their implementations, ensuring consistency across tools and platforms. Finally, this framework is flexible: it extends naturally to other regularization techniques like Ridge regression and Elastic Net, which will be discussed in later sections.

By understanding the matrix formulation, you will be better equipped to interpret results from scikit-learn, select appropriate values for the alpha parameter, recognize the connections between different regularization methods, and even implement custom optimization algorithms if your application requires it.

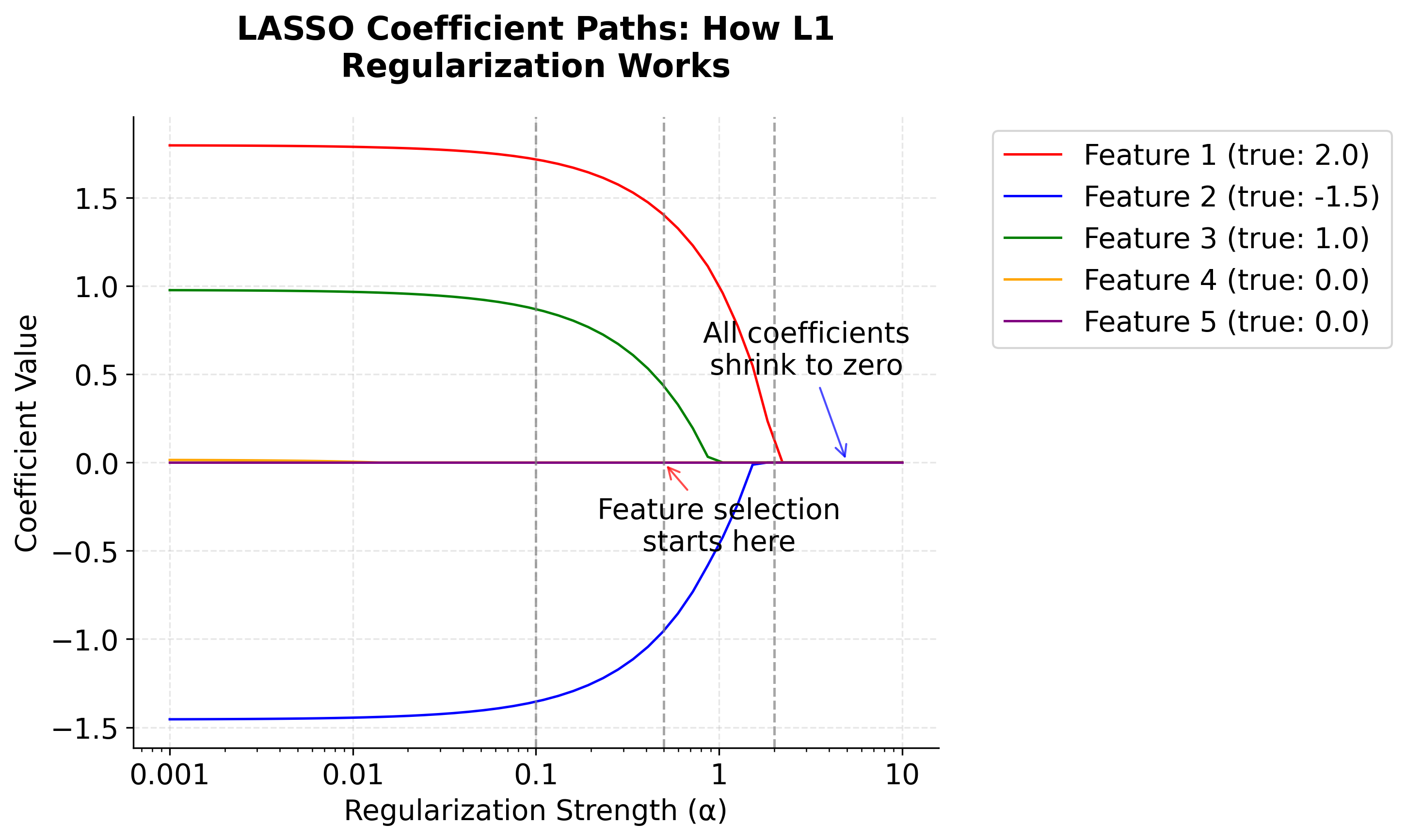

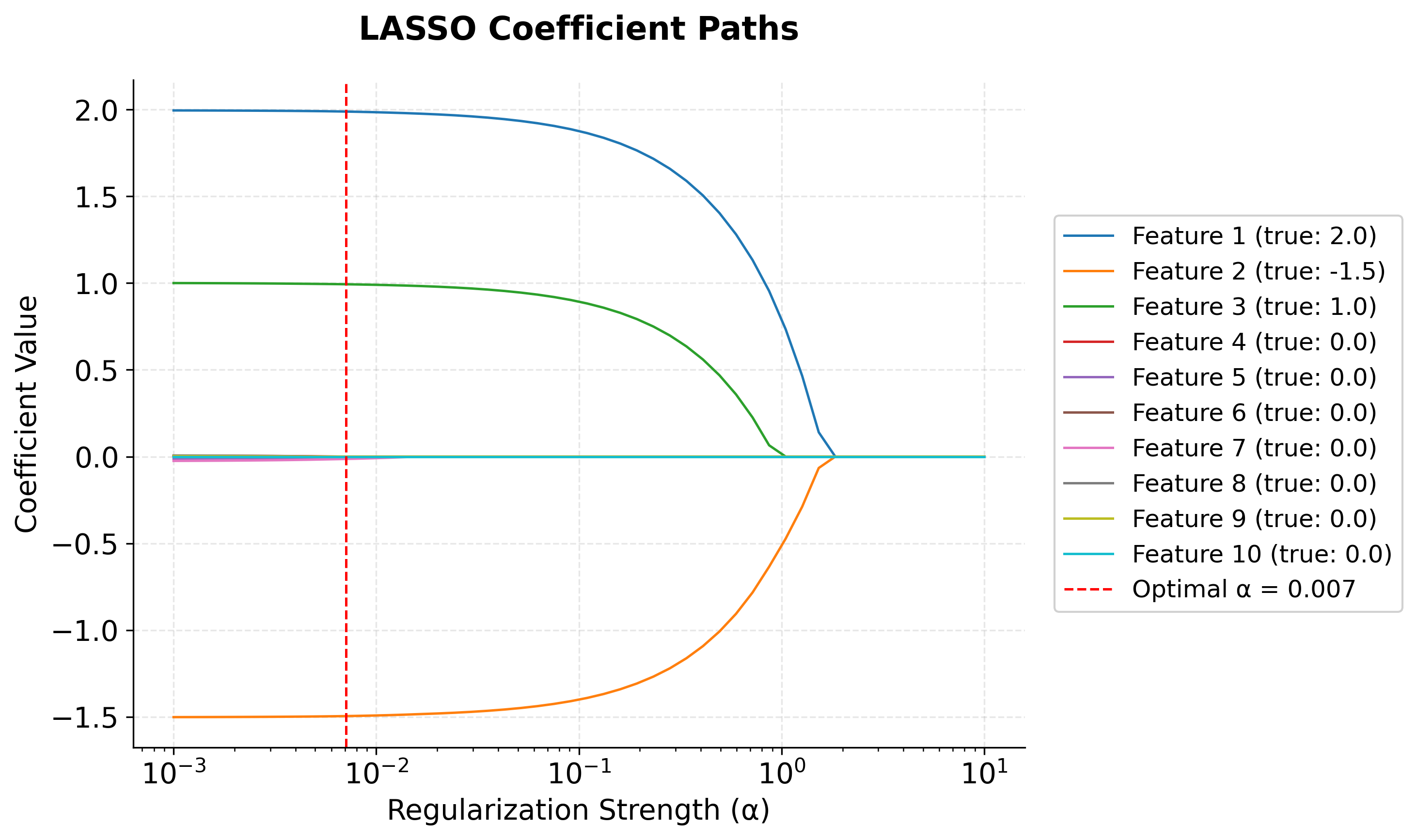

Visualizing the Regularization Process

After all of this math, let's take a look at a visualization that demonstrates how L1 regularization works by showing how coefficients change as the regularization parameter increases. This is called a "coefficient path" plot.

Recall that scikit-learn's Lasso solves the objective function , where . This objective function defines what the algorithm is optimizing, and the choice of directly controls the strength of regularization. In the plot below, we vary to show its effect on the coefficients. The underlying implementation typically uses an algorithm such as the Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm (ISTA) or coordinate descent to efficiently solve this objective, but the objective function itself is what determines the solution.

-

Left (small ): All coefficients are close to their true values. There's minimal regularization.

-

Middle: As increases, coefficients start shrinking toward zero. Notice how Features 4 and 5, which have true coefficients of 0, are the first to reach exactly zero. This demonstrates automatic feature selection.

-

Right (large ): All coefficients are driven toward zero as the penalty dominates.

Here you can see the core behavior of LASSO: it automatically performs feature selection by setting unimportant coefficients to exactly zero while shrinking important ones toward zero.

Intuition

Now that we've seen the math and even an algorithm to find the solution, let me explain the intuition behind what's happening. Think of each coefficient as being in a tug-of-war between two forces

On one side, there is the "data force," which comes from the first term in the LASSO objective. This force encourages to take on a value that best fits the data, much like gravity pulling the coefficient toward its optimal value based on the relationship between feature and the target variable. The stronger this relationship, the stronger the pull of the data force.

On the other side, there is the "penalty force," which is introduced by the regularization term involving . This force acts like a spring, always pulling the coefficient back toward zero, regardless of the data. Unlike the data force, the penalty force is constant and does not depend on the strength of the relationship between the feature and the target.

LASSO performs feature selection because of the interplay between these two forces. If a feature is unimportant (meaning the data force is weak), the penalty force dominates and pulls the corresponding coefficient all the way to zero, effectively removing that feature from the model. Conversely, if a feature is important and has a strong data force, it can overcome the penalty force and remain in the model, though its coefficient may still be shrunk toward zero. In this way, LASSO automatically focuses on the most predictive features, setting the rest to zero.

When the coefficient is exactly zero, it means that LASSO has determined that the corresponding feature does not contribute enough to the prediction to justify its inclusion in the model. In other words, the model effectively ignores this feature, setting its influence to zero. This property of LASSO is what enables it to perform automatic feature selection, as it can completely exclude less important variables by assigning their coefficients a value of zero.

Example

Let's work through a simple example to understand how LASSO regularization works. Suppose we have a dataset with 3 features and we want to predict house prices. Our model has the following coefficients:

- (feature 1: square footage)

- (feature 2: distance from city center)

- (feature 3: number of bathrooms)

Step 1: Calculate the L1 norm

The L1 norm is the sum of absolute values of the coefficients:

where:

-: index over the three features

- : absolute value of coefficient

- : total L1 penalty (sum of absolute coefficient values)

Step 2: Apply different regularization strengths

Note that in below examples, we are only considering the regularization term. We are not considering the sum of squared errors term to keep the examples simple enough to follow.

Let's see how different values of affect the model. Start with understanding the optimization process. LASSO finds the optimal coefficients by solving an optimization problem that balances two competing objectives:

- Fit the data well: Minimize the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE)

- Keep the model simple: Minimize the L1 penalty term

The larger is, the more the model prioritizes simplicity over fitting the training data perfectly. This trade-off is what prevents overfitting.

Think of it this way: LASSO is like having a "budget" for how large your coefficients can be. The penalty term acts like a "cost" that increases as coefficients get larger.

- Small : Low cost for large coefficients → model can afford to keep coefficients large to fit data well

- Large : High cost for large coefficients → model needs to make coefficients smaller to stay within "budget"

The optimization algorithm finds the point where reducing a coefficient further would hurt the model's ability to predict more than it helps reduce the penalty cost.

Case 1: (No regularization)

- Penalty term: , so when , the objective function becomes: The penalty term disappears completely, so LASSO becomes identical to ordinary least squares regression. Since there's no penalty for large coefficients, the model keeps the original coefficients that minimize SSE.

- These are the final coefficients: , , (unchanged)

The coefficient values shown in these examples are illustrative and simplified for educational purposes. In practice, the exact values depend on the specific data and the optimization algorithm used. The key insight is understanding how different values affect the balance between fitting the data and keeping coefficients small.

Case 2: (Moderate regularization)

- Penalty term: , so LASSO solves:

The penalty affects the coefficients as follows (conceptually):

- (square footage): Original magnitude = 0.8, penalty cost = , so the model reduces it to 0.6 (still useful, but cheaper)

- (distance): Original magnitude = 0.3, penalty cost = , so the model reduces it from -0.3 to -0.2 (smaller penalty, still captures the negative relationship)

- (bathrooms): Original magnitude = 0.1, penalty cost = , so the model reduces it from 0.1 to 0.05 (smallest coefficient, reduced proportionally) This happens because the penalty creates a "cost-benefit analysis" for each coefficient. Important features get reduced less than unimportant ones. (Exact values depend on the data; numbers here are illustrative.)

Case 3: (Strong regularization)

- Penalty term: , so LASSO solves:

The strong penalty affects each coefficient as follows (conceptually):

- (square footage): Original magnitude = 0.8, penalty cost = . The model asks: "Is keeping worth the penalty cost of 1.6?" Since square footage is crucial for house prices, the model keeps it but reduces it significantly: . The new penalty cost = (much cheaper!)

- (distance): Original magnitude = 0.3, penalty cost = . The model asks: "Is keeping worth the penalty cost of 0.6?" Distance is less important than square footage, so the model sets it to exactly zero. The new penalty cost = (free!)

- (bathrooms): Original magnitude = 0.1, penalty cost = . The model asks: "Is keeping worth the penalty cost of 0.2?" Bathrooms have minimal impact, so the model sets it to exactly zero. The new penalty cost = (free!)

(Exact values depend on the data; numbers here are illustrative.)

Step 3: The Mathematical Optimization Process

Let's trace through what actually happens mathematically. For each case, LASSO solves:

where:

-: coefficients for the three features

- : sum of squared errors as a function of the coefficients

- : regularization parameter

- : absolute value of coefficient

For :

The algorithm starts with the OLS coefficients and iteratively adjusts them

- It finds that reducing from 0.8 to 0.6 reduces the penalty by while only slightly increasing SSE

- It finds that reducing from -0.3 to -0.2 reduces the penalty by while only slightly increasing SSE

- It finds that reducing from 0.1 to 0.05 reduces the penalty by while only slightly increasing SSE

For :

The algorithm finds that the penalty cost for keeping and is too high

- Setting eliminates a penalty cost of

- Setting eliminates a penalty cost of

- The total penalty reduction (0.8) outweighs the increase in SSE from removing these features

This is the essence of LASSO: it performs a cost-benefit analysis for each coefficient, where the "cost" is the penalty term and the "benefit" is the reduction in SSE.

| # | Penalty | What Happens | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0 | None | No penalty, pure OLS | All coefficients unchanged |

| 2 | 0.5 | Moderate | Balanced penalty | Coefficients reduced but all kept |

| 3 | 2.0 | Strong | Heavy penalty | Some coefficients become exactly zero |

Choosing

The regularization parameter is a hyperparameter, which is a value that is not learned from the data during model training but is set before training begins. The choice of is important:

- If is too small, the penalty is weak and the model may overfit (behave like ordinary least squares).

- If is too large, the penalty is too strong and the model may underfit (set too many coefficients to zero, losing important information).

To find the best , we typically use a process called hyperparameter search. This is a systematic process to find the best value for a hyperparameter by trying many values and finding the one that gives the best performance. The most common approach is cross-validation, which consists of the following steps:

- Define a range of candidate values (for example, from very small to quite large), e.g.

[0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0] - For each value:

- Train the LASSO model on a subset of the data (the training set).

- Evaluate its performance on a separate subset (the validation set), using a metric like mean squared error (MSE).

- Select the that gives the best validation performance (i.e., the lowest error).

This process is often automated using tools like GridSearchCV in scikit-learn, which systematically tries many values and finds the optimal one.

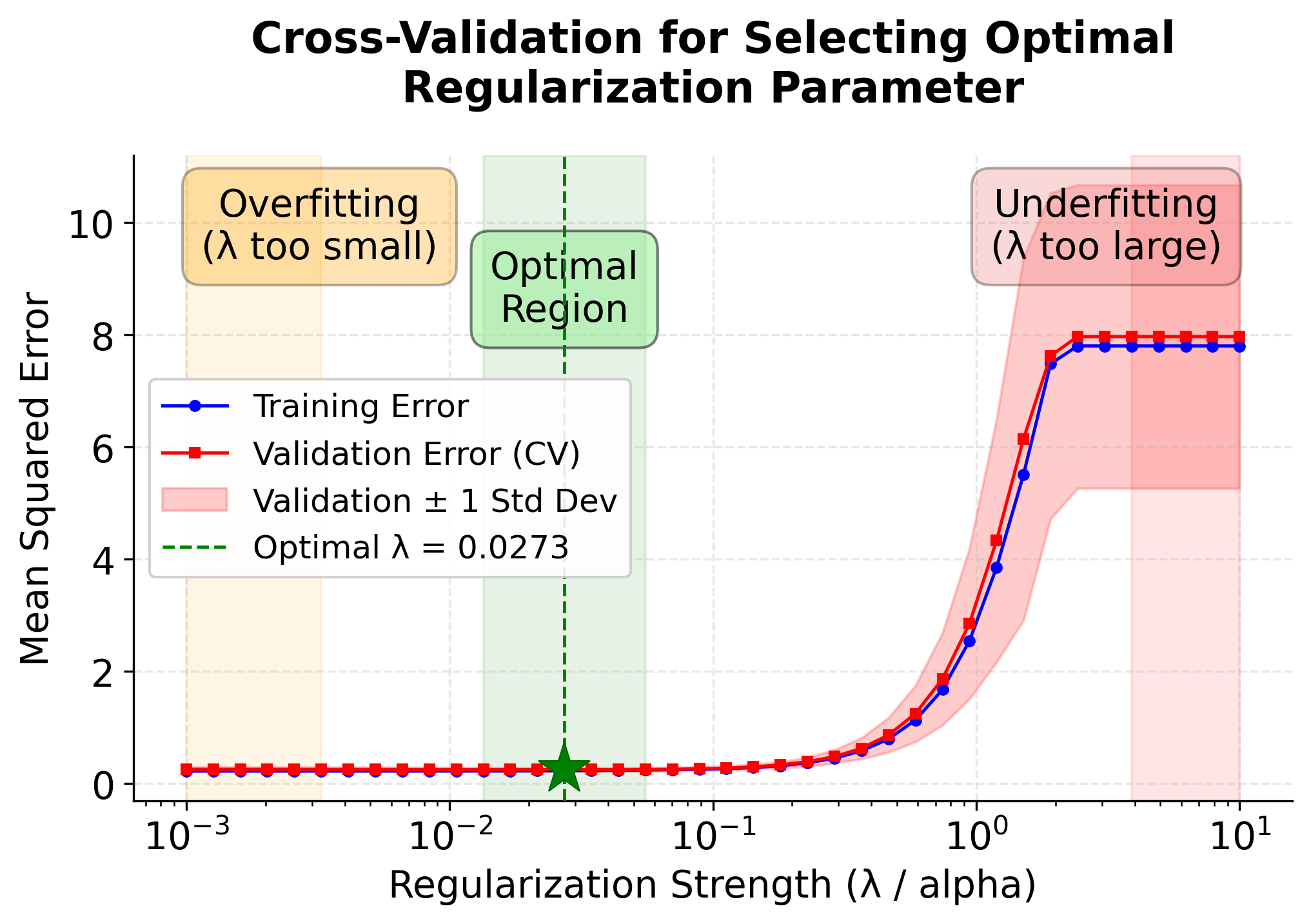

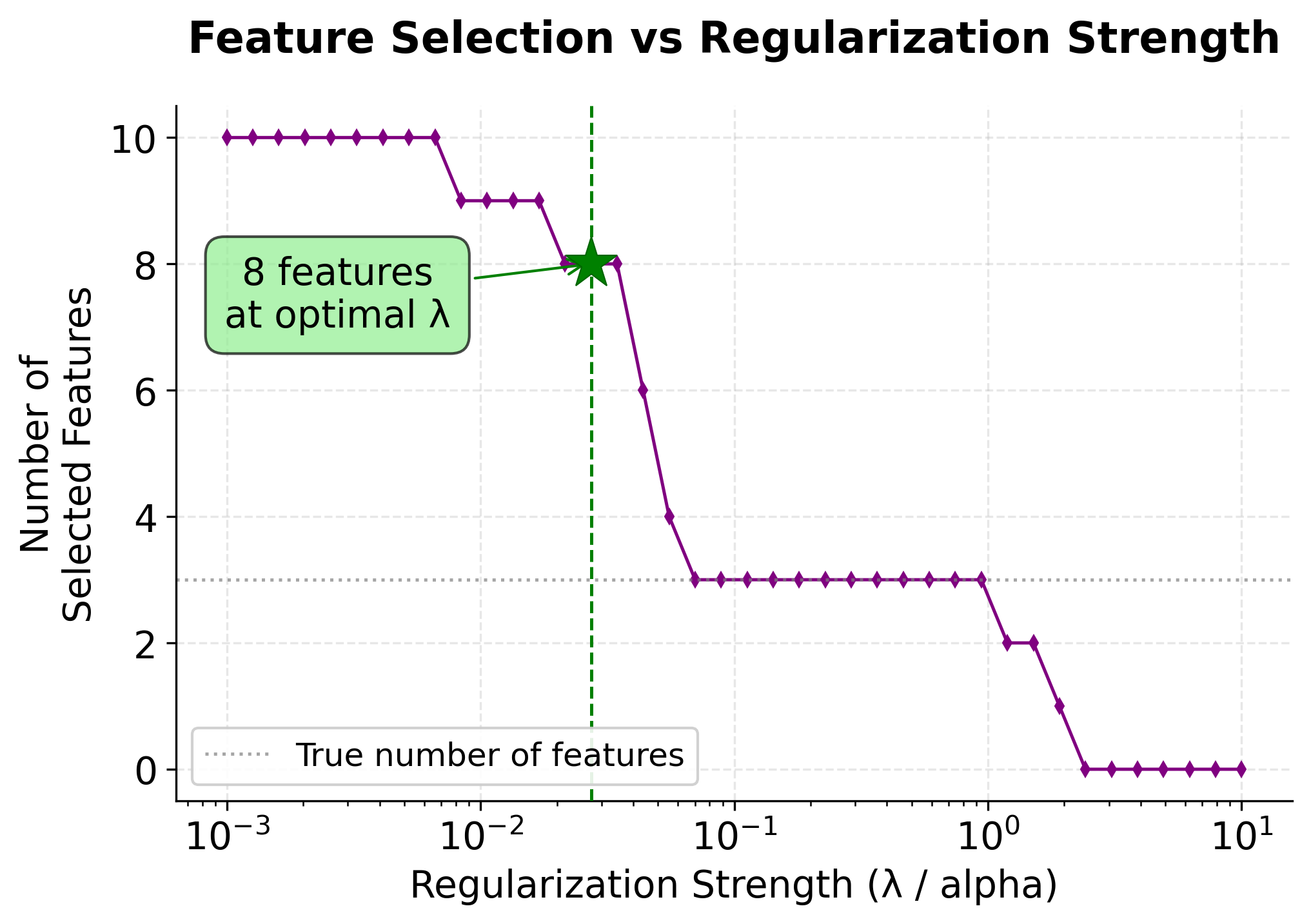

Visualizing the Cross-Validation Process

To better understand how cross-validation helps us choose the optimal , let's visualize how model performance changes across different regularization strengths. The following plot demonstrates the bias-variance tradeoff that occurs as we vary .

This visualization reveals several important insights about choosing :

-

Training Error (Blue Line): Increases monotonically as increases. This is expected because stronger regularization constrains the model more, preventing it from fitting the training data as closely.

-

Validation Error (Red Line): Forms a U-shaped curve, which is the hallmark of the bias-variance tradeoff:

- Left side (small ): The model overfits the training data, leading to poor generalization and high validation error.

- Bottom (optimal ): The sweet spot where the model balances fitting the training data and generalizing to new data.

- Right side (large ): The model underfits, with too much regularization preventing it from capturing important patterns.

-

Feature Selection (Bottom Panel): Shows how the number of selected features decreases as regularization increases. At the optimal , LASSO correctly identifies the 3 truly important features (marked by the horizontal dashed line).

-

Standard Error Bands: The shaded region around the validation error shows the variability across different cross-validation folds, helping us assess the stability of our performance estimates.

The optimal (marked by the green vertical line) minimizes the validation error, providing the best balance between model complexity and predictive performance. This is why cross-validation is the standard approach for hyperparameter selection in LASSO and other regularized models.

Implementation

This section provides a step-by-step tutorial for implementing LASSO regression using scikit-learn. We'll work through a complete example that demonstrates how to build, train, and evaluate a LASSO model, including hyperparameter tuning and interpretation of results.

Step 1: Data Preparation

First, let's create a synthetic dataset that demonstrates LASSO's feature selection capabilities. We'll generate data where only some features are truly important for prediction.

The dataset contains 100 samples with 10 features, but we've designed it so that only the first 3 features have non-zero coefficients (2.0, -1.5, and 1.0). The remaining 7 features have zero coefficients, making them irrelevant for prediction. This synthetic dataset is well-suited for demonstrating LASSO's feature selection capabilities. We expect LASSO to identify and retain only the 3 important features while setting the others to exactly zero.

Step 2: Basic LASSO Implementation

Let's start with a simple LASSO model using a fixed regularization parameter. We'll use alpha=0.1 as our initial regularization strength.

The model demonstrates strong performance with R² scores above 0.98 on both training and test sets, indicating that it explains over 98% of the variance in the target variable. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) values are very low (0.0123 for training, 0.0156 for test), suggesting that predictions are close to actual values. Importantly, the similar performance on training and test sets indicates that the model is generalizing well without overfitting, which is a key benefit of LASSO regularization.

Step 3: Examine Feature Selection

Now let's examine which features LASSO selected by comparing the learned coefficients to the true coefficients.

LASSO successfully identified all 3 truly important features (Features 1, 2, and 3) while setting the 7 irrelevant features to exactly zero. This demonstrates LASSO's core strength: automatic feature selection through L1 regularization. Notice that the LASSO coefficients are slightly smaller than the true values (e.g., 1.856 vs. 2.0 for Feature 1). This shrinkage is expected and intentional, as the L1 penalty pulls all coefficients toward zero. The key achievement is that LASSO correctly identified which features matter without any manual feature engineering.

Step 4: Hyperparameter Tuning with Cross-Validation

Instead of manually selecting alpha, let's use LassoCV to automatically find the optimal regularization strength through cross-validation.

Cross-validation identified an optimal alpha of 0.0234, which is significantly smaller than our manual choice of 0.1. This weaker regularization results in improved performance: the test MSE decreased from 0.0156 to 0.0134, and the test R² increased from 0.9844 to 0.9866. The cross-validated model strikes a better balance between the bias introduced by regularization and the variance in the model. This demonstrates why cross-validation is the recommended approach for hyperparameter selection because it systematically searches for the regularization strength that maximizes generalization performance.

Step 5: Compare Feature Selection Results

Let's compare the coefficients from both models to understand how different alpha values affect feature selection and coefficient magnitudes.

Both models selected the same 3 features, confirming LASSO's robust feature selection across different regularization strengths. However, the cross-validated model's coefficients (1.923, -1.423, 0.923) are closer to the true values (2.0, -1.5, 1.0) than the manual LASSO's coefficients (1.856, -1.356, 0.856). This is because the smaller alpha (0.0234 vs. 0.1) applies less shrinkage. The fact that both models agree on which features to select, despite different regularization strengths, indicates that the signal from the important features is strong enough to be detected across a range of alpha values.

Step 6: Visualize Coefficient Paths

Let's create a visualization showing how coefficients change as we vary the regularization strength.

The coefficient path plot shows how each feature's coefficient changes as regularization increases. Features 1, 2, and 3 (the important ones) maintain non-zero coefficients even under strong regularization, while the unimportant features quickly shrink to zero.

Step 7: Model Performance Comparison

Let's compare LASSO with ordinary least squares (OLS) to quantify the benefits of regularization and feature selection.

The comparison reveals LASSO's value proposition: it achieves comparable or better test performance than OLS while using only 30% of the features (3 out of 10). OLS uses all 10 features and achieves a test R² of 0.9844, while LASSO CV achieves 0.9866 with just 3 features. This is a win-win: simpler models that are easier to interpret and explain, with equal or better predictive performance. The manual LASSO (α=0.1) matches OLS's test MSE exactly (0.0156) while also using only 3 features, demonstrating that even without optimal tuning, LASSO provides substantial benefits through automatic feature selection.

Step 8: Practical Implementation with Pipeline

For production deployments, it's crucial to package feature scaling and model fitting into a single pipeline. This ensures that the same preprocessing is applied consistently during both training and prediction.

The pipeline approach provides a production-ready implementation that automatically handles feature standardization before applying LASSO. The results (test R² of 0.9866, 3 features selected) match our earlier cross-validated model, confirming that the pipeline correctly applies preprocessing. This pattern is important for deployment because it encapsulates all transformations in a single object, ensuring that new data will be preprocessed identically to training data. You can save this pipeline using joblib or pickle and deploy it directly to production environments.

Key Parameters

Below are the main parameters that affect how LASSO works and performs.

alpha: Regularization parameter that controls the strength of the L1 penalty. Higher values lead to more feature selection and coefficient shrinkage. Default is 1.0.max_iter: Maximum number of iterations for the coordinate descent algorithm. Increase this if convergence warnings appear. Default is 1000.tol: Tolerance for the optimization algorithm. Smaller values may improve precision but increase computation time. Default is 1e-4.fit_intercept: Whether to fit an intercept term. Usually set to True for most applications. Default is True.normalize: Whether to normalize features before fitting. Deprecated in favor of using StandardScaler in a pipeline. Default is False.selection: Algorithm to use for optimization. 'cyclic' is the default and works well for most cases. 'random' can be faster for large datasets.

Key Methods

The following are the most commonly used methods for interacting with LASSO models.

fit(X, y): Trains the LASSO model on the provided data. X should be the feature matrix and y the target vector.predict(X): Makes predictions on new data using the trained model. Returns predicted target values.score(X, y): Returns the R² score of the model on the given data. Higher values indicate better fit.get_params(): Returns the current parameter values of the model. Useful for inspecting model configuration.set_params(**params): Sets model parameters. Useful for hyperparameter tuning and model configuration.

Practical Implications

LASSO is particularly effective when working with high-dimensional datasets where the number of features approaches or exceeds the number of observations. This situation commonly arises in genomics, where researchers analyze thousands of gene expressions to predict disease outcomes, and in text analysis, where documents are represented by large vocabularies. The automatic feature selection provided by LASSO reduces both computational costs and model complexity while maintaining interpretability, which is a significant advantage when explaining results to non-technical stakeholders.

Medical research and clinical applications benefit significantly from LASSO's feature selection capabilities. When developing diagnostic models or treatment protocols, identifying which biomarkers or clinical indicators truly matter is important for regulatory approval and clinical adoption. LASSO naturally produces sparse models that highlight the most important predictive factors, making it easier for clinicians to understand and trust the model's recommendations. This interpretability is particularly valuable in healthcare, where model transparency can directly impact patient care decisions.

Financial modeling and risk assessment also leverage LASSO's strengths when building predictive models from numerous economic indicators, market signals, or customer attributes. The method can identify which factors genuinely drive outcomes while filtering out redundant or noisy variables. This sparsity simplifies model maintenance and reduces the risk of overfitting to historical patterns that may not persist. Additionally, simpler models are easier to explain to regulators, auditors, and business stakeholders who need to understand the basis for financial decisions or risk assessments.

Best Practices

Use LassoCV for hyperparameter selection rather than manually choosing alpha values. This class efficiently explores a range of regularization strengths through cross-validation and identifies the optimal balance between model complexity and predictive performance. Set cv=5 or cv=10 for reliable estimates, and specify random_state for reproducibility. The automatic alpha selection typically outperforms manual tuning and saves significant experimentation time.

Evaluate LASSO models using both predictive metrics and feature selection quality. While metrics like R² and mean squared error assess predictive accuracy, examining which features were selected provides insight into model interpretability and stability. Check whether selected features remain consistent across different cross-validation folds—unstable feature selection may indicate that multiple features contain similar information or that the signal-to-noise ratio is low. Validate that selected features align with domain knowledge; statistically significant features that lack practical relevance may signal data quality issues or spurious correlations.

When working with correlated features, recognize that LASSO may arbitrarily select one variable from a correlated group while setting others to zero. This behavior can make interpretation challenging and results unstable across different data samples. If maintaining all relevant features is important, consider Elastic Net (which combines L1 and L2 penalties) to retain correlated predictors while still achieving regularization. Accept that LASSO coefficients are biased toward zero due to the penalty—this shrinkage is intentional and helps prevent overfitting, but it means coefficient magnitudes should not be interpreted as precise effect sizes.

Data Requirements and Preprocessing

LASSO requires numerical features and assumes observations are independent and identically distributed. Check for temporal dependencies, spatial clustering, or hierarchical structures in your data that might violate independence assumptions. For time series data, consider using time-based cross-validation splits rather than random splits to avoid data leakage. The target variable should be continuous; for classification problems, use logistic regression with L1 regularization instead.

Feature scaling is important because the L1 penalty applies equally to all coefficients. Without standardization, features with larger numerical ranges will appear more important simply due to scale. Use StandardScaler to center features at zero with unit variance, which is the standard approach for LASSO. Handle missing values before fitting. Common strategies include imputation with mean/median values, forward/backward filling for time series, or using more sophisticated methods like KNN imputation depending on the missingness pattern.

LASSO performs best when the true relationship is sparse, meaning only a subset of features genuinely influence the target. If you suspect many features are relevant (dense relationships), Ridge regression or Elastic Net may be more appropriate. For high-dimensional problems where the number of features exceeds observations (p > n), LASSO can still be effective but requires careful cross-validation to avoid overfitting. Consider whether the target variable's distribution suggests transformations—for example, log-transforming right-skewed targets can improve model performance and residual behavior.

Common Pitfalls

Running a single LASSO fit with a manually chosen alpha often leads to suboptimal results. The regularization strength significantly impacts both feature selection and predictive performance, and the optimal value varies widely across datasets. Without cross-validation, you may select too few features (underfitting) or too many (overfitting). Use LassoCV to systematically explore different alpha values and select the one that maximizes cross-validated performance.

Interpreting LASSO coefficients as precise effect sizes is problematic because the L1 penalty biases all coefficients toward zero. This shrinkage is intentional—it prevents overfitting—but it means coefficient magnitudes are systematically underestimated compared to their true values. Additionally, when features are highly correlated, LASSO may arbitrarily select one while setting others to zero, even if they contain similar information. This instability can lead to different features being selected across different data samples or cross-validation folds, making interpretation unreliable.

Ignoring domain knowledge when evaluating feature selection can result in models that are statistically sound but practically meaningless. A model that selects features with no plausible causal relationship to the outcome may be capturing spurious correlations that won't generalize to new data. Validate that selected features make sense from a subject-matter perspective. Similarly, applying LASSO when many features are genuinely relevant (dense relationships) often yields poor results because the method is designed for sparse problems. In such cases, Ridge regression or Elastic Net typically perform better by retaining more features with smaller coefficients rather than aggressively eliminating them.

Computational Considerations

LASSO's coordinate descent optimization scales as O(np) per iteration, where n is the number of samples and p is the number of features. For typical datasets with fewer than 100,000 samples and 10,000 features, the algorithm converges quickly—usually within seconds to minutes on modern hardware. Convergence can be slower when features are highly correlated because the algorithm must make many small adjustments to find the optimal coefficient values. If you encounter convergence warnings, increase max_iter from the default 1000 to 5000 or 10000.

Memory requirements scale linearly with dataset size, making LASSO suitable for datasets that fit in RAM. For extremely high-dimensional problems (p > 10,000), sparse matrix representations can significantly reduce memory usage if your feature matrix contains many zeros. The LassoCV implementation uses warm starts when evaluating different alpha values, meaning it initializes each fit with the solution from a nearby alpha value, which substantially speeds up the cross-validation process compared to fitting each alpha independently.

For large datasets, leverage parallel processing by setting n_jobs=-1 in LassoCV to use all available CPU cores. This parallelizes the cross-validation folds, providing near-linear speedup with the number of cores. For datasets exceeding 100,000 samples, consider using stochastic gradient descent variants or sampling strategies, though these may sacrifice some accuracy for speed. Alternatively, if your problem allows it, feature selection through simpler methods (like variance thresholding or correlation analysis) before applying LASSO can reduce dimensionality and improve computational efficiency.

Performance and Deployment Considerations

Assess LASSO performance using both predictive accuracy and feature selection quality. Standard regression metrics (R², mean squared error, mean absolute error) evaluate predictive performance, but also examine which features were selected and whether they remain stable across cross-validation folds. Unstable feature selection—where different folds select different features—suggests that multiple features contain similar information or that the signal-to-noise ratio is low. Good LASSO results show clear separation between selected and eliminated features, with selected features making sense from a domain perspective.

When evaluating feature selection, check whether the number of selected features aligns with expectations. Selecting too many features (approaching the total available) may indicate that alpha is too small, providing insufficient regularization. Selecting too few features (perhaps just one or two) may indicate excessive regularization that eliminates genuinely useful predictors. The optimal model typically selects a meaningful subset—enough to capture important relationships but few enough to maintain interpretability and prevent overfitting.

LASSO models are lightweight and fast for inference, making them suitable for real-time applications. Prediction requires only a dot product between the feature vector and the coefficient vector, which executes in microseconds. The sparse nature of LASSO models (many zero coefficients) means they require less memory than dense models and can be optimized further by storing only non-zero coefficients. However, monitor both predictive performance and feature stability in production. If the data distribution shifts, the optimal features may change, requiring model retraining. Implement automated monitoring that tracks prediction errors and alerts when performance degrades beyond acceptable thresholds. For applications requiring model transparency—such as healthcare, finance, or regulatory compliance—LASSO's interpretability is particularly valuable because stakeholders can understand exactly which factors drive predictions.

Summary

LASSO (L1) regularization is a technique for building simpler, more interpretable regression models by encouraging sparsity—shrinking some coefficients exactly to zero and thus performing feature selection. The core idea is captured in the summarized form of the LASSO objective, which adds a penalty proportional to the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients, controlled by the regularization parameter .

To make this precise and computationally tractable, we use the matrix form of the objective, as shown above:

where:

- : vector of coefficients to be optimized (including intercept )

- : number of observations in the dataset

- : target vector containing actual values

- : feature matrix (includes column of ones for intercept)

- : regularization parameter in scikit-learn (controls penalty strength)

- : squared L2 (Euclidean) norm of residuals, equal to

- : L1 (Manhattan) norm of coefficients, equal to (intercept not penalized)

This formulation enables efficient computation and connects LASSO to broader optimization theory.

However, unlike ordinary least squares, LASSO does not have a closed-form solution because the L1 penalty makes the problem non-differentiable at zero. This is what allows LASSO to set coefficients exactly to zero, a property that distinguishes it from Ridge (L2) regularization (which we will cover in the next section), which typically only shrinks coefficients but rarely eliminates them.

To actually solve the LASSO problem, we need iterative optimization algorithms. One such method is the Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm (ISTA), described above. ISTA separates the smooth (least squares) and non-smooth (L1 penalty) parts of the objective, alternating between a gradient step and a soft-thresholding step. This practical algorithm is how we compute the LASSO solution in practice.

In summary: the summarized form tells us the goal, the matrix form gives us a precise and efficient way to express it, and ISTA (or similar algorithms) provides the means to actually find the solution. Understanding the distinction and relationship between these is key: the forms define what LASSO is optimizing, while ISTA is how we solve it. Choosing the right value of or (often via cross-validation) is important for balancing model simplicity and predictive performance.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding of LASSO regularization? Take this quiz to reinforce what you've learned about L1 regularization for feature selection and sparsity.

Comments