A comprehensive guide to multinomial logistic regression covering mathematical foundations, softmax function, coefficient estimation, and practical implementation in Python with scikit-learn.

This article is part of the free-to-read Machine Learning from Scratch

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Multinomial Logistic Regression

Multinomial logistic regression is a powerful extension of binary logistic regression that allows us to model relationships between multiple categorical outcomes and predictor variables. While binary logistic regression handles situations with exactly two possible outcomes (like "yes" or "no"), multinomial logistic regression extends this capability to handle three or more mutually exclusive categories. This makes it invaluable for classification problems where we need to predict which of several possible classes an observation belongs to.

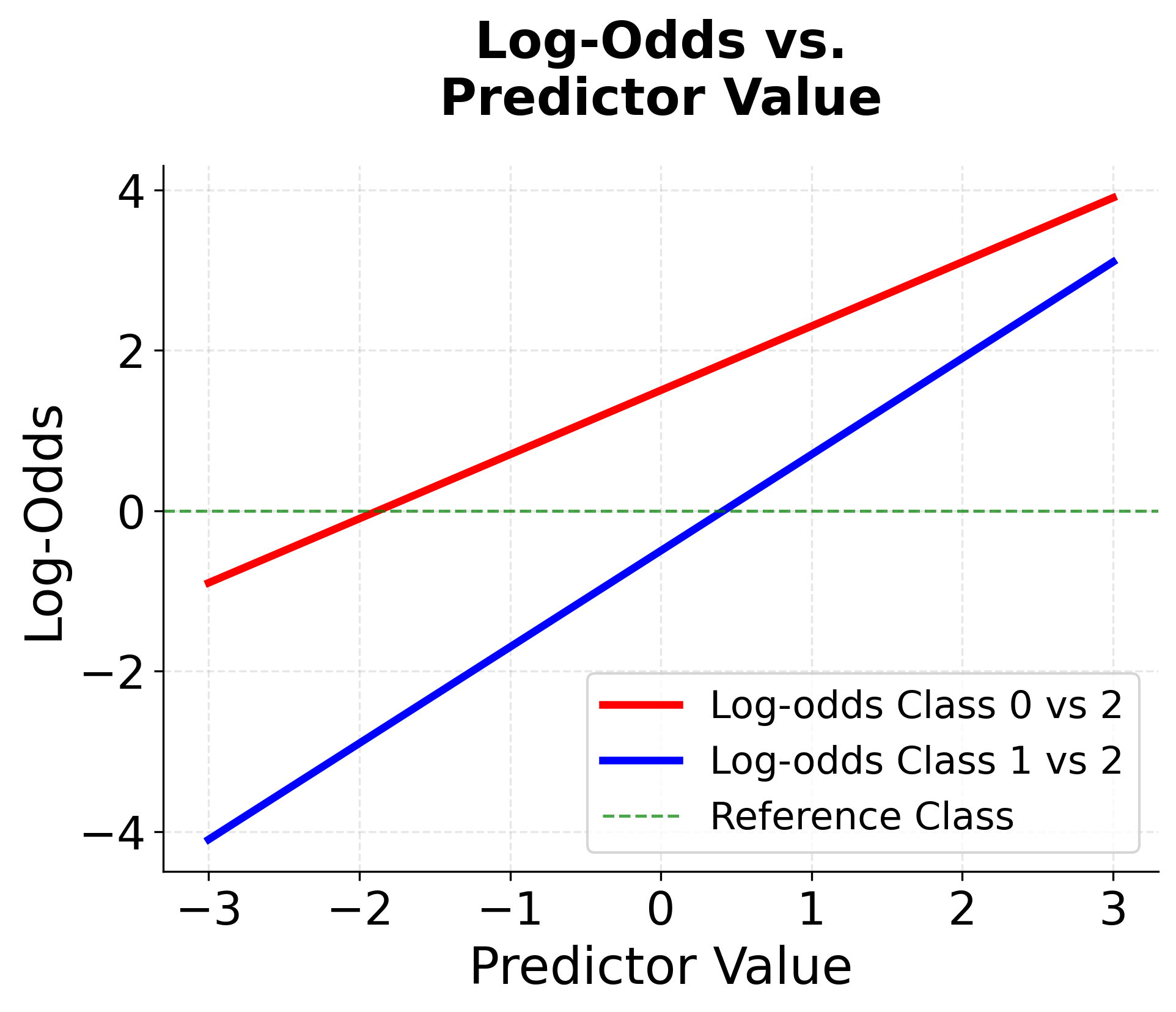

The key insight behind multinomial logistic regression is that we can model the probability of each category relative to a reference category. Unlike binary logistic regression, which uses a single logistic function, multinomial logistic regression uses multiple logistic functions simultaneously. Each function represents the log-odds of one category compared to the reference category, creating a system of equations that must be solved together.

This approach is particularly useful in fields like marketing (predicting customer segments), medicine (diagnosing disease types), and natural language processing (classifying text into different topics). The model assumes that the categories are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive, meaning each observation must belong to exactly one category, and all possible categories are included in the model.

Advantages

Multinomial logistic regression offers several compelling advantages over alternative classification methods. First, it provides interpretable probability estimates for each class, not just the predicted class. This probabilistic output is crucial in many applications where we need to understand the confidence of our predictions or make decisions based on uncertainty. For example, in medical diagnosis, knowing that a patient has a 60% chance of having condition A, 30% chance of condition B, and 10% chance of condition C is much more informative than simply predicting condition A.

Second, the model naturally handles the constraint that all class probabilities must sum to one, ensuring that our predictions are mathematically consistent. This built-in constraint prevents the common problem of having probabilities that don't add up correctly, which can occur with other multi-class approaches that treat each class independently. Additionally, multinomial logistic regression can handle both categorical and continuous predictor variables seamlessly, making it flexible for diverse datasets.

Finally, the model provides direct interpretability through odds ratios, allowing us to understand how changes in predictor variables affect the relative probability of different outcomes. This interpretability is particularly valuable in fields where understanding the relationship between variables is as important as making accurate predictions.

Disadvantages

Despite its strengths, multinomial logistic regression has several limitations that practitioners should consider. The most significant disadvantage is the assumption of independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA), which states that the relative probabilities of any two alternatives should not change when a third alternative is added or removed. This assumption can be violated in many real-world scenarios, particularly when alternatives are similar or when there are unobserved factors that affect multiple alternatives similarly.

Another limitation is the model's sensitivity to the choice of reference category. While the choice of reference category doesn't affect the overall model fit, it can significantly impact the interpretation of coefficients and odds ratios. This can make model interpretation more complex, especially when communicating results to stakeholders who may not be familiar with the reference category concept.

Additionally, multinomial logistic regression can become computationally intensive as the number of categories increases, since we need to estimate parameters for each category relative to the reference. The model also assumes linear relationships between the log-odds and predictor variables, which may not hold in all situations. When these assumptions are violated, the model's performance can degrade significantly, and alternative approaches like decision trees or neural networks might be more appropriate.

Formula

The mathematical foundation of multinomial logistic regression builds upon the principles of binary logistic regression, but extends them to handle multiple categories. Let's walk through the derivation step by step, starting with the most intuitive form and progressing to the matrix notation.

Basic Probability Model

We begin with the fundamental assumption that we have categories (where ) and want to model the probability that observation belongs to category . Let's denote this probability as , where represents the vector of predictor variables for observation .

The key insight is that we can model the log-odds of each category relative to a reference category. Without loss of generality, let's choose category as our reference category. The log-odds of category relative to category is:

where:

- is the probability that observation belongs to category given its predictor values (the conditional probability we're modeling for the non-reference category)

- is the probability that observation belongs to the reference category (the baseline category against which all others are compared)

- is the intercept for category (the baseline log-odds when all predictors are zero)

- is the coefficient for predictor in category (quantifies the effect of predictor on the log-odds of category relative to the reference category)

- is the value of predictor for observation (the observed feature value)

- is the total number of predictor variables (the dimensionality of the feature space)

- is the reference category (chosen arbitrarily, typically the last category, with all its coefficients set to zero for identifiability)

From Log-Odds to Probabilities

To convert these log-odds back to probabilities, we need to solve for . Let's define the linear predictor for category as:

where:

- is the linear predictor for observation and category (a real-valued quantity that can take any value from to , representing the log-odds before normalization)

Then we can write:

Taking the exponential of both sides:

This gives us:

Normalization Constraint

Since all probabilities must sum to one, we have:

Substituting our expression for :

Since is common to all terms, we can factor it out:

This gives us the probability of the reference category:

Final Probability Formula

Now we can express the probability of any category as:

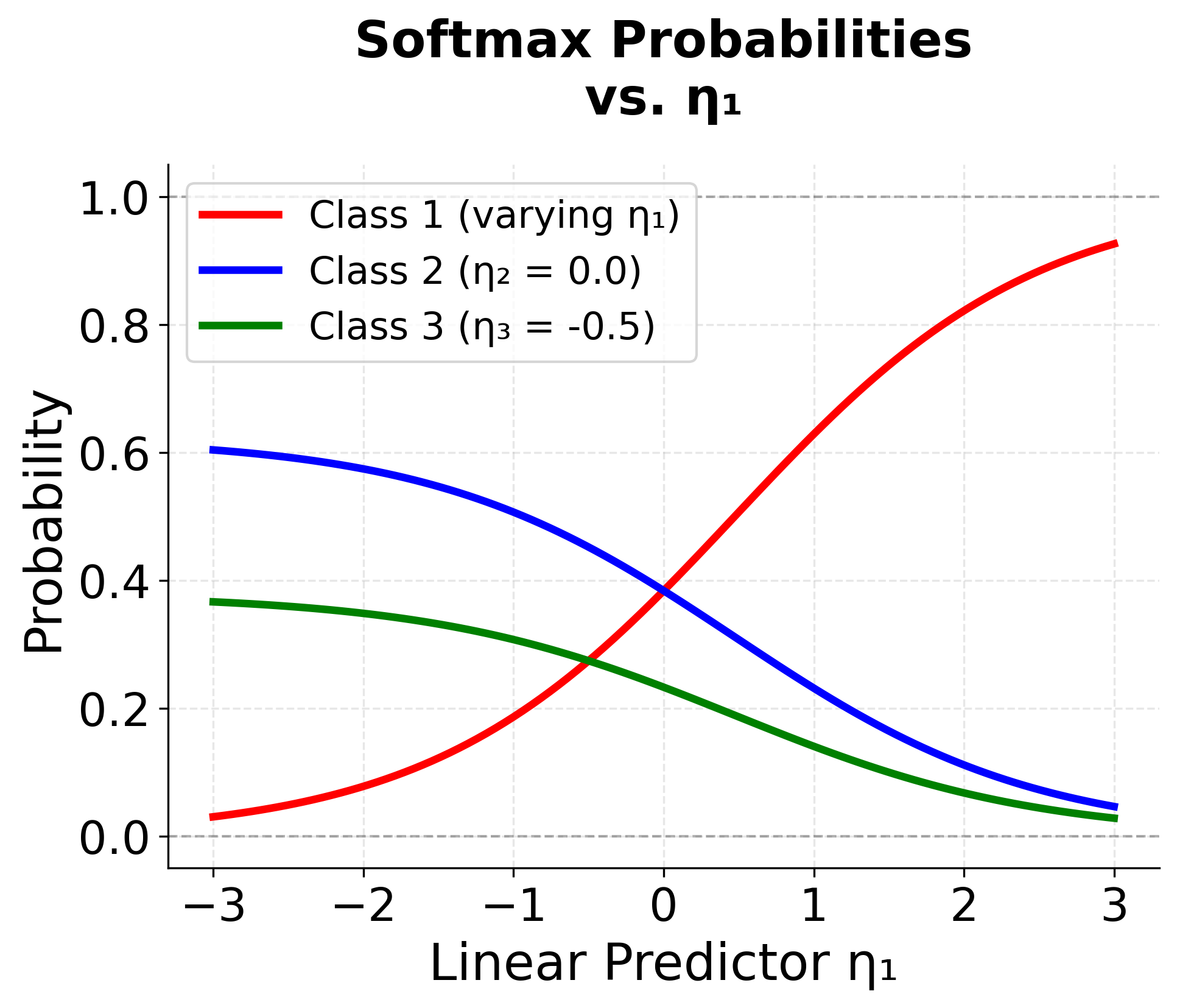

This is the softmax function, which ensures that all probabilities sum to one and are non-negative. Notice that when , this reduces to the standard logistic regression formula.

Matrix Notation

For computational efficiency and clarity, we can express the multinomial logistic regression model in matrix notation.

Let be the design matrix, where is the number of observations and is the number of predictors (the extra column accounts for the intercept). For each non-reference category (where ), let be a vector of coefficients. We stack these coefficient vectors horizontally to form a coefficient matrix:

where:

- is the design matrix (includes a column of 1s for the intercept term, allowing matrix multiplication to compute all linear predictors)

- is the number of observations in the dataset (the sample size)

- is the number of predictor variables (the number of features, excluding the intercept)

- is the coefficient vector for category (includes the intercept as the first element, followed by slope coefficients)

- is the coefficient matrix for all non-reference categories (each column is a coefficient vector for one non-reference category)

- is the total number of categories (including the reference category)

The linear predictors for all observations and all non-reference categories can be computed as:

where:

- is the matrix of linear predictors (each row corresponds to one observation, each column corresponds to one non-reference category, and element is the linear predictor for observation and category )

To obtain the predicted probabilities for all categories, we apply the softmax function row-wise. For each observation and category :

where for the reference category , we set (since its coefficients are all zero by convention).

In matrix notation, the full probability matrix , with elements , is given by:

where:

- is the probability matrix (each row contains the predicted probabilities for one observation across all categories)

- is the probability that observation belongs to category (an element of the probability matrix)

- is the matrix formed by horizontally concatenating (the matrix of linear predictors for non-reference categories) with (a column of zeros for the reference category)

- is the column vector of zeros for the reference category (representing for all observations)

- is the softmax function applied row-wise (transforms linear predictors into probabilities that are non-negative and sum to 1 for each observation)

This formulation ensures that all predicted probabilities are non-negative and sum to one for each observation.

This matrix-based approach is highly efficient for computation, especially when working with large datasets or when fitting the model using optimization algorithms that require gradients with respect to all parameters.

Calculating the Coefficients

The coefficients in multinomial logistic regression are estimated using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). This process involves finding the parameter values that maximize the likelihood of observing our data given the model.

Likelihood Function

For a dataset with observations and classes, the likelihood function is:

where:

- is the likelihood function (the probability of observing the entire dataset given the model parameters )

- represents all coefficient parameters in the model (the collection of all values for all non-reference categories and all predictors)

- is the number of observations (the sample size)

- is the number of categories (the total number of possible outcome classes)

- is the predicted probability that observation belongs to category (computed using the softmax function)

- is the indicator function that equals 1 if observation truly belongs to class , and 0 otherwise (selects the probability of the observed class)

Log-Likelihood Function

Working with the log-likelihood is computationally more convenient:

where:

- is the log-likelihood function (the natural logarithm of the likelihood function, which transforms products into sums for computational convenience and numerical stability)

Substituting the softmax probability formula:

Gradient and Hessian

To find the maximum likelihood estimates, we need the gradient (first derivatives) and Hessian (second derivatives) of the log-likelihood function.

Let's break down how to compute the gradient and Hessian of the multinomial logistic regression log-likelihood step by step.

Step 1: Recall the log-likelihood

The log-likelihood for multinomial logistic regression is:

where is 1 if observation belongs to class , and 0 otherwise.

Step 2: Substitute the softmax probability

Recall that

where:

- is the linear predictor for observation and category (computed as the dot product of the feature vector and coefficient vector)

- is the transpose of the feature vector for observation (a row vector including a 1 for the intercept)

- is the coefficient vector for category (a column vector including the intercept and slope coefficients)

Step 3: Compute the gradient (first derivative) with respect to

We want to find the derivative of the log-likelihood with respect to a particular coefficient (the coefficient for predictor in class ):

-

The log-likelihood for a single observation is:

-

The derivative with respect to is:

-

Since depends on all , but only directly on through , we use the chain rule.

-

The derivative of with respect to is:

(This comes from differentiating the log-softmax.)

-

Summing over all observations, we get:

Step 4: Compute the Hessian (second derivative) with respect to and

- The Hessian entry for parameters and is the second derivative:

- Differentiating the gradient again, we get: where is 1 if , and 0 otherwise.

Results:

-

Gradient (First Derivatives):

where:

- is the partial derivative of the log-likelihood with respect to coefficient (the gradient component for this parameter)

- is the coefficient for predictor in category (the parameter we're taking the derivative with respect to)

- is the value of predictor for observation (the feature value that multiplies this coefficient)

- is the indicator function (equals 1 if observation truly belongs to category , and 0 otherwise)

- is the predicted probability for observation in category (computed using the current parameter values)

-

Hessian (Second Derivatives):

where:

- is the second partial derivative of the log-likelihood (measures the curvature of the log-likelihood surface with respect to parameters and )

- is the coefficient for predictor in category (the second parameter in the mixed partial derivative)

- is the value of predictor for observation (the feature value that multiplies coefficient )

- is the indicator function (equals 1 if categories and are the same, and 0 otherwise)

Optimization Methods

The coefficients are found by maximizing the log-likelihood function using numerical optimization methods:

- Newton-Raphson Method: Uses both gradient and Hessian information for faster convergence

- Fisher Scoring: Uses the expected Fisher information matrix instead of the observed Hessian

- Gradient Descent: Iteratively updates parameters in the direction of the gradient

- Limited-memory BFGS (L-BFGS): A quasi-Newton method that approximates the Hessian

Iterative Reweighted Least Squares (IRLS)

Multinomial logistic regression can also be solved using IRLS, which reformulates the problem as a series of weighted least squares problems. This approach:

- Starts with initial coefficient estimates

- Computes fitted probabilities using the current coefficients

- Creates working responses and weights

- Solves a weighted least squares problem

- Updates the coefficients

- Repeats until convergence

Convergence Criteria

The optimization process continues until one of the following convergence criteria is met:

- Parameter convergence:

- Log-likelihood convergence:

- Gradient convergence:

where:

- is the vector of coefficient estimates at iteration (the current parameter values during optimization)

- is the vector of coefficient estimates at iteration (the updated parameter values after one optimization step)

- is the log-likelihood value at iteration (the objective function value at the current parameters)

- is the log-likelihood value at iteration (the objective function value at the updated parameters)

- is the gradient vector at iteration (the vector of partial derivatives of the log-likelihood with respect to all parameters)

- is the tolerance threshold (a small positive number, typically or , that determines when convergence is achieved)

- denotes the absolute value (for scalars) or norm (for vectors), measuring the magnitude of change

Identifiability and Constraints

The multinomial logistic regression model is said to be overparameterized because, without any constraints, there are more parameters in the model than are actually needed to describe the relationship between the predictors and the outcome categories. Specifically, for outcome categories, the model estimates a separate set of coefficients for each category, but only of these sets are necessary to uniquely determine the predicted probabilities. This redundancy means that different sets of coefficients can produce the same predicted probabilities, making the model unidentifiable unless we impose a constraint.

To resolve this, the standard approach is to set the coefficients for one of the categories—called the reference category—to zero:

where:

- is the coefficient vector for the reference category (a vector set to all zeros to ensure model identifiability)

- is the zero vector (a vector with all elements equal to zero)

By doing this, we remove the redundancy and ensure that the model is identifiable, meaning the optimization problem has a unique solution and the estimated coefficients are interpretable relative to the reference category.

Mathematical Properties

The multinomial logistic regression model has several important mathematical properties. First, the softmax function ensures that all predicted probabilities are between 0 and 1 and sum to 1, which is necessary for a valid probability model. Second, the model is identifiable only up to the choice of reference category - we can add any constant to all coefficients without changing the predicted probabilities, which is why we typically set the coefficients for the reference category to zero.

The model also exhibits the property of proportional odds in the sense that the ratio of probabilities for any two categories depends only on the difference in their linear predictors. This means that if we change a predictor variable, the relative probabilities of all non-reference categories change proportionally, maintaining their relative relationships.

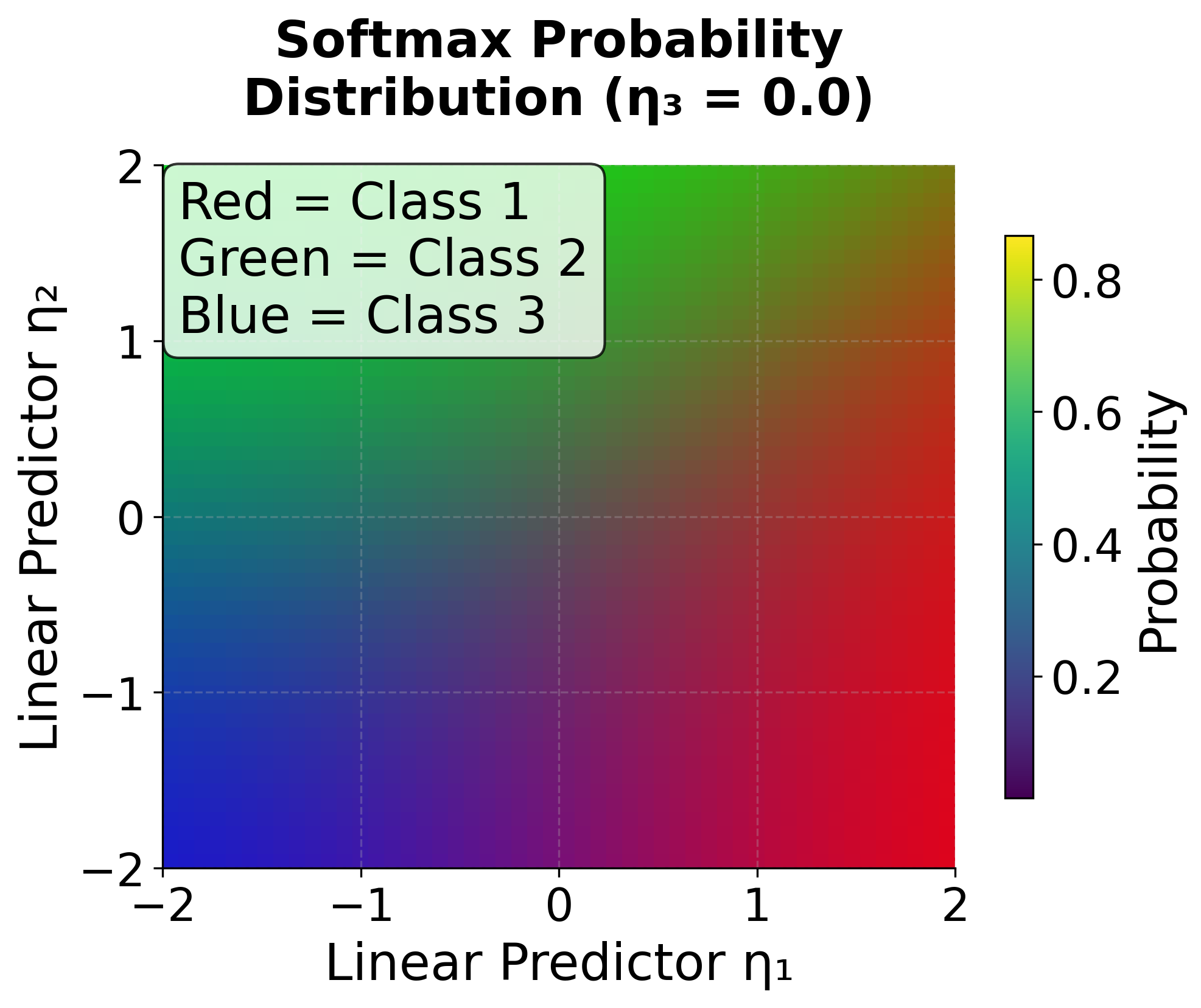

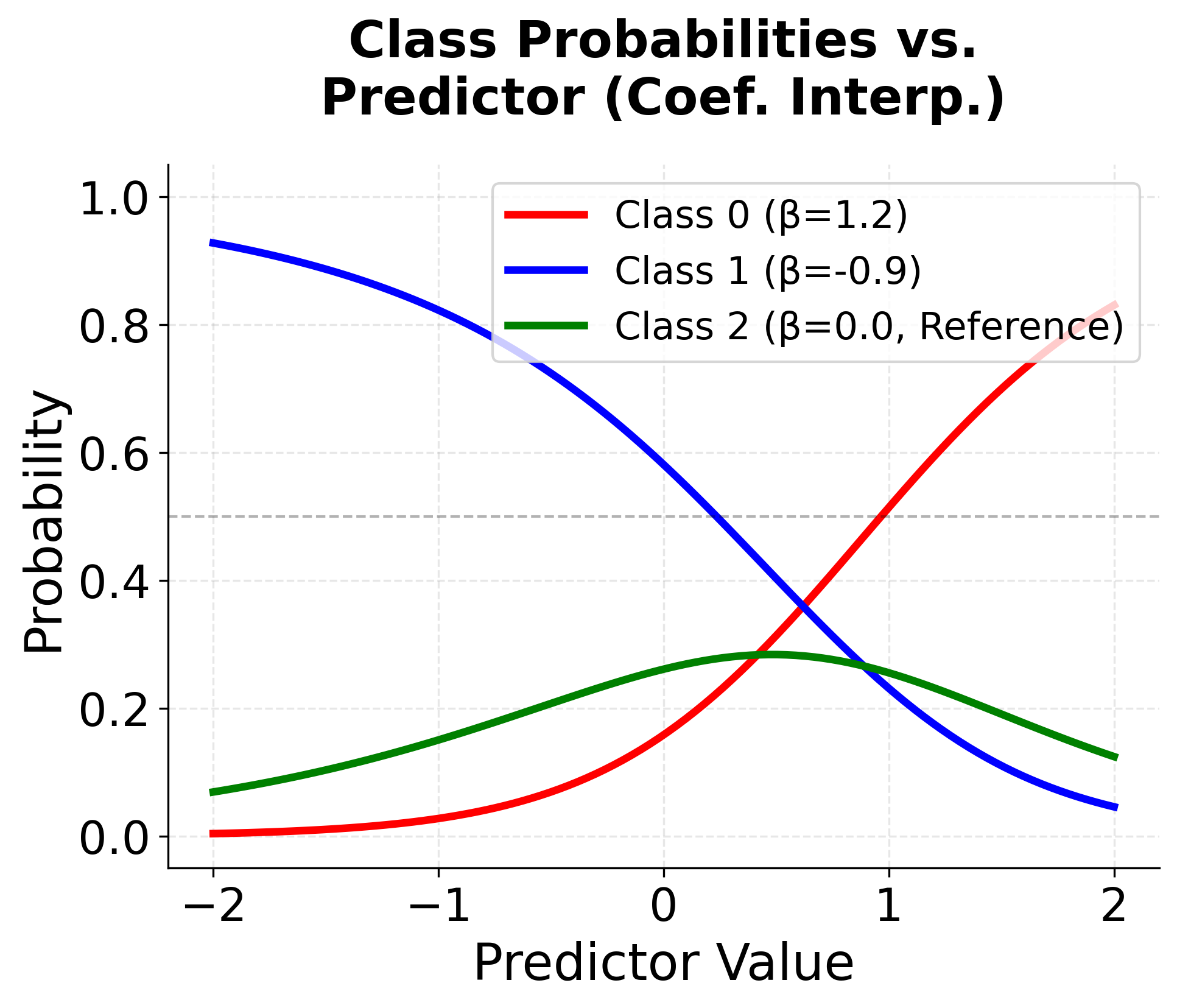

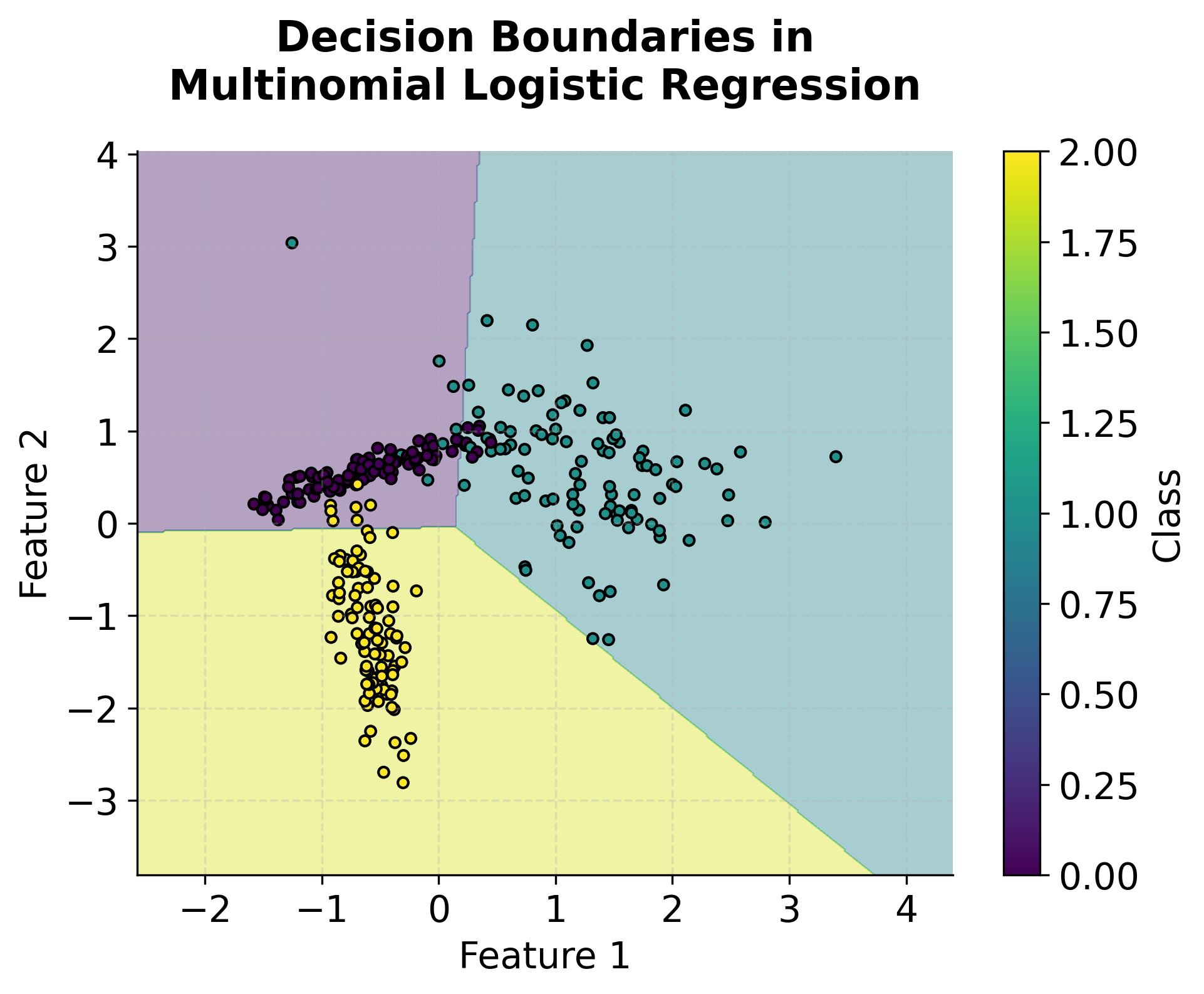

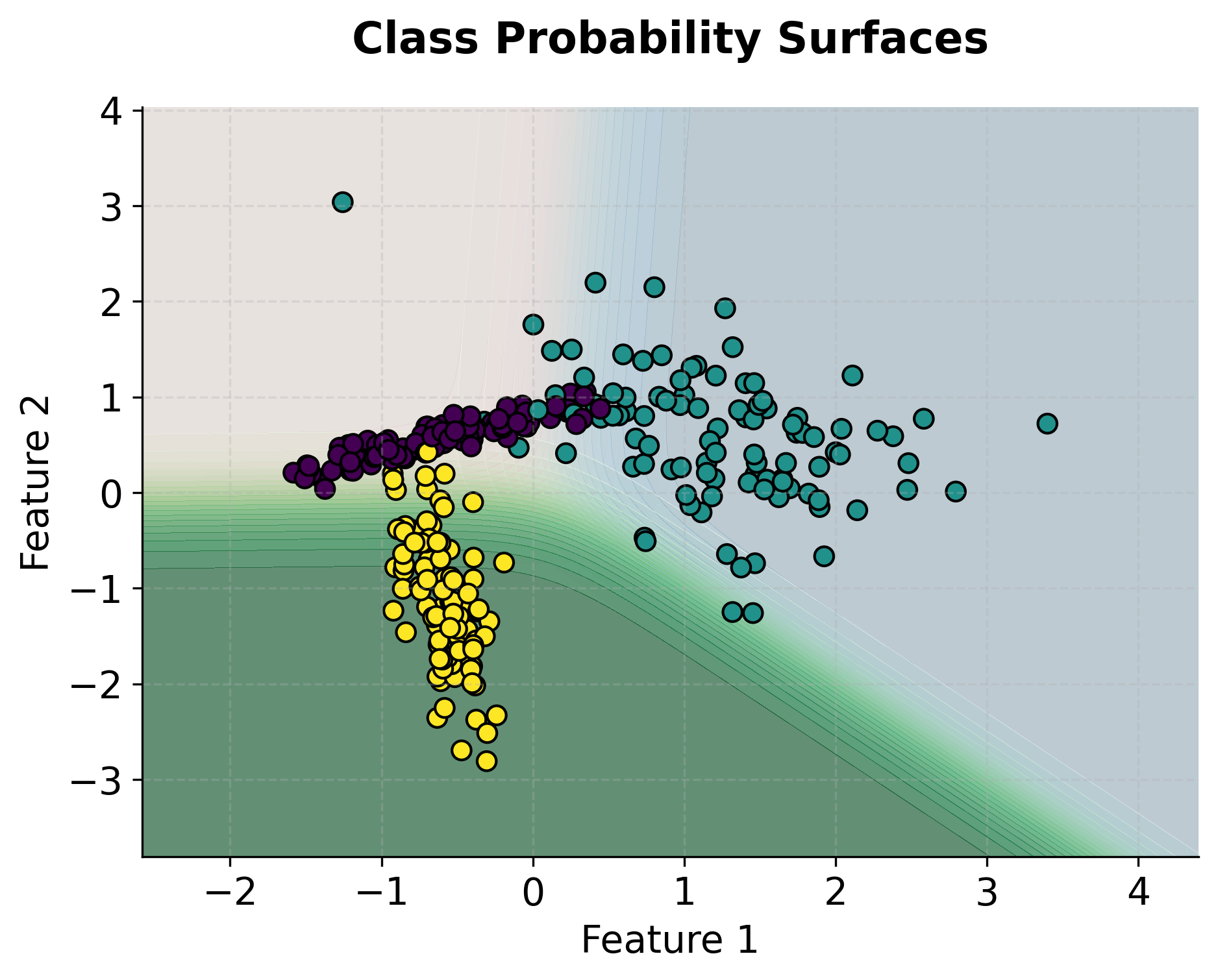

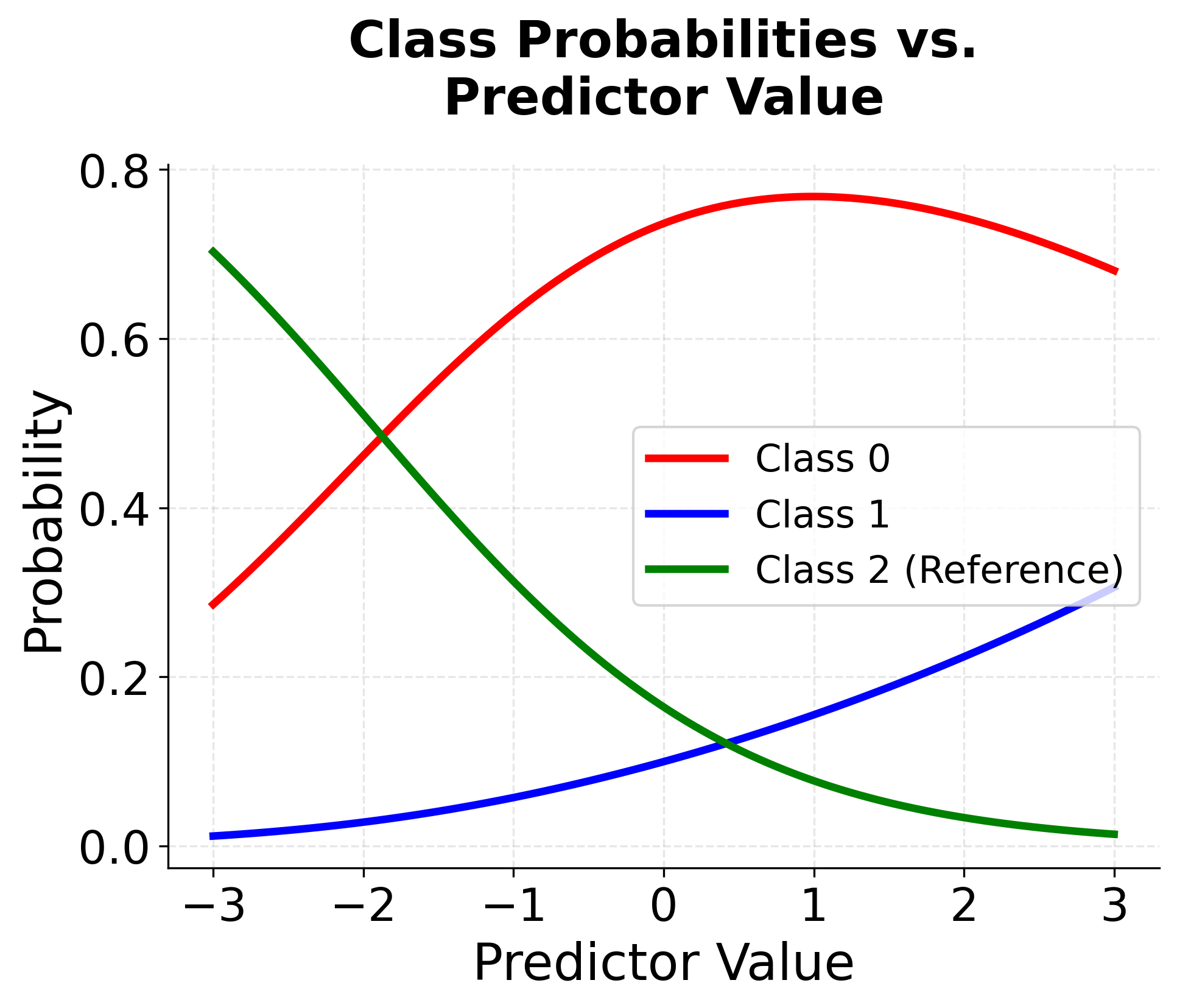

Visualizing Multinomial Logistic Regression

Let's create visualizations to understand how multinomial logistic regression works with different numbers of categories and how the decision boundaries are formed.

Example

Let's work through a concrete example to understand how multinomial logistic regression works with actual numbers. We'll use a simple dataset with two predictor variables and three classes to make the calculations manageable.

Dataset Setup

Suppose we have a dataset with two features (age and income) and three possible outcomes (low, medium, high risk). We'll use "low" as our reference category and calculate the probabilities for "medium" and "high" risk.

| Age | Income | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|

| 25 | 30 | low |

| 30 | 40 | low |

| 35 | 50 | low |

| 40 | 60 | medium |

| 45 | 70 | medium |

| 50 | 80 | medium |

| 25 | 35 | medium |

| 30 | 45 | medium |

| 35 | 55 | high |

| 40 | 65 | high |

| 45 | 75 | high |

| 50 | 85 | high |

Coefficient Estimation

As mentioned in the formula section earlier, the coefficients in multinomial logistic regression are found by solving an optimization problem that maximizes the likelihood of the observed data. In practice, this is done using numerical algorithms such as Newton-Raphson or gradient-based methods, which iteratively adjust the coefficients to best fit the data.

For this example, let's assume we have already obtained the estimated coefficients. We'll now use these given coefficients to demonstrate how to calculate the predicted probabilities for a new observation.

Manual Calculation

Now let's manually calculate the multinomial logistic regression for an observation with age = 25 and income = 30 using these estimated coefficients:

Coefficients for medium vs low (reference):

- (intercept)

- (age coefficient)

- (income coefficient)

Coefficients for high vs low (reference):

- (intercept)

- (age coefficient)

- (income coefficient)

Step-by-Step Calculation

Step 1: Calculate Linear Predictors

For our observation with age = 25 and income = 30, we calculate the linear predictor for each category:

where:

- is the linear predictor for the medium risk category (the log-odds of medium risk relative to low risk before normalization)

- is the intercept for medium risk (the baseline log-odds when age and income are both zero)

- is the age coefficient for medium risk (the change in log-odds for each one-year increase in age)

- is the income coefficient for medium risk (the change in log-odds for each one-unit increase in income)

Substituting the values:

Similarly for high risk:

where:

- is the linear predictor for the high risk category (the log-odds of high risk relative to low risk before normalization)

- is the intercept for high risk (the baseline log-odds when age and income are both zero)

- is the age coefficient for high risk (the change in log-odds for each one-year increase in age)

- is the income coefficient for high risk (the change in log-odds for each one-unit increase in income)

Substituting the values:

For the reference category (low risk):

where:

- is the linear predictor for the low risk category (set to 0 because low risk is the reference category)

Step 2: Calculate Exponentials

We apply the exponential function to each linear predictor:

where:

- is Euler's number (approximately 2.71828)

- is the exponential of the linear predictor for medium risk (used in the softmax numerator)

where:

- is the exponential of the linear predictor for high risk (used in the softmax numerator)

where:

- is the exponential of the linear predictor for low risk (equals 1 because )

Step 3: Calculate Denominator

The denominator of the softmax function is the sum of all exponentials:

where:

- is the sum of exponentials across all categories (the normalization constant in the softmax function)

- is the total number of categories (low, medium, high)

Substituting the values:

Step 4: Calculate Probabilities

Using the softmax formula, we calculate the probability for each category:

where:

- is the predicted probability of low risk for this observation (computed by dividing the exponential of the low risk linear predictor by the sum of all exponentials)

where:

- is the predicted probability of medium risk for this observation (computed by dividing the exponential of the medium risk linear predictor by the sum of all exponentials)

where:

- is the predicted probability of high risk for this observation (computed by dividing the exponential of the high risk linear predictor by the sum of all exponentials)

Step 5: Verification

We verify that all probabilities sum to 1, as required by the softmax function:

Interpretation

The calculations show that for a 25-year-old with income 30, the model predicts:

- 5.5% probability of low risk

- 24.5% probability of medium risk

- 70.0% probability of high risk

The predicted class would be "high" since it has the highest probability. Notice how the probabilities sum to exactly 1, which is a fundamental property of the multinomial logistic regression model.

Implementation in Scikit-learn

Scikit-learn provides an efficient implementation of multinomial logistic regression through the LogisticRegression class. In this section, we'll walk through a complete example using a customer risk classification dataset, demonstrating how to prepare data, train the model, and interpret results.

Data Preparation

First, we'll create our dataset and prepare it for modeling. We'll use age and income as predictors to classify customers into three risk categories:

The LabelEncoder converts the categorical risk levels into numerical values (0, 1, 2), which is required for scikit-learn's implementation. We use stratified splitting to ensure all three risk categories appear in both training and test sets, which is important for reliable evaluation with small datasets.

Model Training

Now let's train the multinomial logistic regression model using the L-BFGS solver, which is well-suited for small to medium-sized datasets:

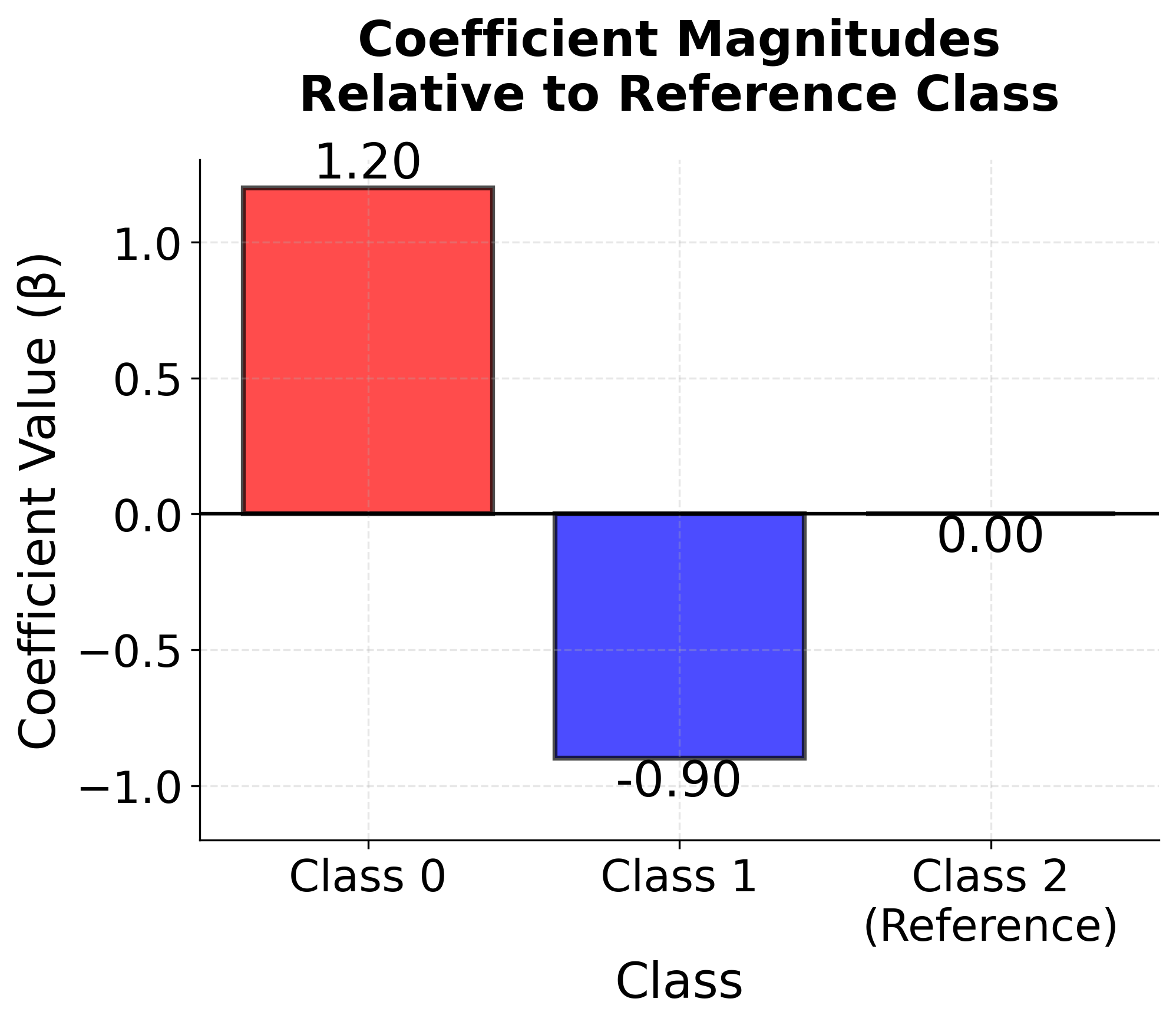

Model Coefficients

Let's examine the learned coefficients for each class to understand how age and income influence risk classification:

The coefficients reveal how each feature affects the log-odds of each class relative to the reference class (class 0, which corresponds to "high" risk in this encoding). Positive coefficients increase the probability of that class as the feature value increases, while negative coefficients decrease it. For instance, if the age coefficient for the "low" risk class is positive, older customers are more likely to be classified as low risk compared to the reference category. The intercepts represent the baseline log-odds when all features equal zero.

Model Performance

Let's evaluate the model's performance on the test set:

The test accuracy indicates how often the model correctly predicts the risk category. In this case, the model achieves reasonable accuracy despite the very small dataset size. The log loss measures the quality of the probability predictions—lower values indicate better calibrated probabilities, with values closer to 0 being preferable. The small difference between training and test accuracy (if any) suggests the model is not overfitting significantly, which is encouraging given the limited data.

Predictions and Probabilities

Let's examine individual predictions to understand how the model assigns probabilities:

Each prediction shows the complete probability distribution across all three risk categories. The model assigns the observation to the class with the highest probability, but the full distribution provides valuable information about prediction confidence. For example, if one class has a probability of 0.9, the model is very confident, whereas probabilities of 0.4, 0.35, and 0.25 indicate high uncertainty. Notice how the probabilities sum to 1.0 by construction, which is a fundamental property of the softmax function used in multinomial logistic regression.

Classification Report

The classification report provides detailed performance metrics for each class:

The classification report provides a comprehensive view of model performance broken down by class:

- Precision measures how many predicted instances of a class were actually correct. High precision means the model rarely misclassifies other categories as this one (few false positives).

- Recall measures how many actual instances of a class were correctly identified. High recall means the model rarely misses instances of this class (few false negatives).

- F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single balanced metric. It's particularly useful when you want to balance the trade-off between precision and recall.

- Support shows the number of actual instances of each class in the test set, which helps contextualize the other metrics.

The confusion matrix visualizes where the model makes mistakes. Each row represents the true class, and each column represents the predicted class. Diagonal elements (top-left to bottom-right) show correct predictions, while off-diagonal elements reveal specific misclassification patterns. For example, if the model frequently confuses "medium" risk with "high" risk, you'll see a large value in the corresponding off-diagonal position.

The relatively low performance in this example is due to the very small dataset (only 12 observations). In practice, multinomial logistic regression requires substantially more data to learn meaningful patterns and achieve good generalization performance.

Key Parameters

Below are the main parameters that control how multinomial logistic regression works in scikit-learn.

-

solver: Algorithm for optimization (default: 'lbfgs'). Choose 'lbfgs' or 'newton-cg' for small to medium datasets with L2 regularization. Use 'saga' for large datasets or when L1 regularization is needed. As of scikit-learn 1.5, the multinomial case is handled automatically. Avoid 'liblinear' for multinomial problems as it uses one-vs-rest instead. -

penalty: Type of regularization (default: 'l2'). Options are 'l1', 'l2', 'elasticnet', or None. L2 regularization prevents overfitting by penalizing large coefficients. L1 can perform feature selection by driving some coefficients to zero. Note that not all solvers support all penalty types. -

C: Inverse of regularization strength (default: 1.0). Smaller values specify stronger regularization. Start with 1.0 and adjust based on cross-validation. Common values to try: 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10.0, 100.0. -

max_iter: Maximum number of iterations for solver convergence (default: 100). Increase if you get convergence warnings. Values of 1000 or higher may be needed for complex datasets or stochastic solvers. -

random_state: Seed for reproducibility (default: None). Set to an integer (e.g., 42) to ensure consistent results across runs, especially important when using stochastic solvers like 'sag' or 'saga'. -

class_weight: Weights for each class (default: None). Use 'balanced' to automatically adjust weights inversely proportional to class frequencies, which helps with imbalanced datasets. Can also provide a dictionary with custom weights. -

tol: Tolerance for stopping criteria (default: 1e-4). The optimization stops when the change in coefficients or loss is smaller than this value. Smaller values lead to more precise solutions but longer training times.

Key Methods

The following methods are commonly used when working with multinomial logistic regression models.

-

fit(X, y): Trains the model on feature matrix X and target vector y. The target should be encoded as integers (useLabelEncoderfor categorical targets). -

predict(X): Returns predicted class labels for input data X. The model assigns each observation to the class with the highest predicted probability. -

predict_proba(X): Returns probability estimates for each class. Output is an array where each row sums to 1.0, representing the probability distribution across all classes. Useful for understanding prediction confidence and setting custom decision thresholds. -

predict_log_proba(X): Returns log-probabilities for each class. More numerically stable thanpredict_probawhen working with very small probabilities. -

score(X, y): Returns the mean accuracy on the given test data and labels. Provides a quick evaluation, though detailed metrics (precision, recall, F1) are often needed for multi-class problems. -

decision_function(X): Returns the decision function values (linear predictors) for each class before applying the softmax transformation. Useful for understanding raw model outputs.

Practical Applications

Practical Implications

Multinomial logistic regression is effective for classifying observations into three or more mutually exclusive categories while maintaining interpretability. The model works well when understanding the relationship between predictors and outcomes is as important as achieving high accuracy. In marketing applications, it is commonly used for customer segmentation, where the probabilistic output provides not only the most likely segment but also the relative likelihood of alternatives. This information supports targeted marketing strategies and resource allocation by quantifying uncertainty in segment membership.

In healthcare settings, the model supports diagnostic classification when patients might have one of several possible conditions. The probability estimates quantify diagnostic uncertainty, which can guide the ordering of additional tests or inform treatment decisions when differential diagnosis requires considering multiple possibilities. The interpretable coefficients allow clinicians to understand which patient characteristics most strongly predict each condition, facilitating evidence-based practice and supporting clinical reasoning.

The model is also applied in natural language processing for multi-class text classification, including document categorization, sentiment analysis, and customer support ticket routing. The linear relationship between features and log-odds makes it straightforward to identify which terms or features are most predictive of each category. This interpretability is valuable when you need to explain classification decisions or validate that the model is learning meaningful patterns rather than artifacts in the data.

Best Practices

Select your solver based on dataset size and regularization needs. For small to medium datasets (fewer than 10,000 observations), the lbfgs solver with L2 regularization provides a good balance of speed and performance. For larger datasets or when L1 regularization is needed for feature selection, use the saga solver, which handles stochastic optimization more efficiently. Set max_iter to at least 1000 to help ensure convergence, and monitor for convergence warnings that may indicate the need for additional iterations or adjusted feature scaling.

Regularization helps prevent overfitting, particularly with high-dimensional data or when the number of features approaches the number of observations. Start with the default regularization strength (C=1.0) and use cross-validation to tune this parameter. Smaller values of C increase regularization strength, which can help when you have many correlated features or limited training data. When domain knowledge suggests that only a subset of features is relevant, L1 regularization (penalty='l1') can perform automatic feature selection by driving some coefficients to zero, though this requires using a compatible solver like saga.

For model evaluation, avoid relying solely on overall accuracy, especially with imbalanced classes. Use class-specific metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score to understand performance for each category separately. The predict_proba method provides probability estimates that can be used to set custom decision thresholds based on the costs of different error types. Use stratified cross-validation to ensure each fold maintains the class distribution, which is important when some classes are rare. Consider log loss to evaluate the quality of probability predictions, not just the final class assignments.

Data Requirements and Preprocessing

The target variable should consist of mutually exclusive categories, with each observation belonging to exactly one class. The model works best with at least 10-15 observations per predictor variable per class. With fewer observations, coefficient estimates can become unstable and the model may struggle to learn reliable patterns. The model assumes a linear relationship between predictors and the log-odds of each category. When continuous variables exhibit non-linear relationships with the outcome, consider creating polynomial features or using spline transformations to capture these patterns.

Feature scaling is recommended when using regularization. While the model is not inherently sensitive to feature scales, regularization penalizes all coefficients equally, meaning features with larger scales will be penalized less in absolute terms. Standardizing features to have mean zero and unit variance ensures that regularization affects all features proportionally. The model is also sensitive to multicollinearity among predictors, which can lead to unstable coefficient estimates and inflated standard errors. Check for high correlations between predictors and consider removing redundant features when multicollinearity is severe.

For categorical predictors, use one-hot encoding for nominal variables (categories with no inherent order) and ordinal encoding for ordinal variables (categories with a meaningful order). Note that ordinal encoding imposes a linear relationship between the encoded values and the log-odds. The target variable should be encoded as integers, which LabelEncoder handles automatically. Address missing values before modeling through imputation or by creating indicator variables for missingness if the pattern is informative. Outliers in continuous predictors can disproportionately influence coefficient estimates, so consider robust scaling methods or outlier detection when extreme values are present.

LabelEncoder and OrdinalEncoder are both used to convert categorical data into numerical values, but they have different roles:

- LabelEncoder is designed for encoding the target variable (the labels/classes) in classification problems. It assigns each unique class label an integer value (e.g., 'cat', 'dog', 'mouse' → 0, 1, 2). It operates on 1D arrays (the target vector) only.

- OrdinalEncoder is intended for encoding categorical input features (predictor variables). It transforms each unique value in each feature column into an integer and can process multiple columns at once. It should be used for input features, not the target.

Use LabelEncoder for the target variable, and OrdinalEncoder for input features.

Common Pitfalls

Neglecting to check for convergence warnings during model training can lead to unreliable coefficients and inaccurate predictions. When the optimization algorithm fails to converge within the specified number of iterations, this often indicates that max_iter is set too low (the default of 100 is often insufficient) or that features are not properly scaled. Monitor for convergence warnings and increase max_iter or adjust feature scaling as needed. Another common issue is using the wrong solver for your regularization choice—for example, attempting to use L1 regularization with the lbfgs solver, which only supports L2 regularization. Match your solver to your regularization needs: use saga for L1 or elastic net regularization, and lbfgs or newton-cg for L2 regularization.

Misinterpreting the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumption can lead to inappropriate model applications. This assumption states that the relative probability of choosing between two alternatives should not be affected by the presence or absence of other alternatives. In practice, this can be violated when categories are similar or when unobserved factors affect multiple categories similarly. For example, in transportation mode choice, adding a new bus route might affect both existing bus and train ridership in ways that violate IIA. When you suspect IIA violations, consider alternative models like nested logit or mixed logit, or test the assumption by estimating the model on subsets of categories and checking if coefficients remain stable.

Relying solely on overall accuracy when evaluating model performance is problematic, particularly with imbalanced classes. A model that simply predicts the majority class for all observations can achieve high overall accuracy while performing poorly on minority classes. Use class-specific metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score to understand performance for each category separately. Similarly, failing to use stratified cross-validation can result in some folds having very few or no examples of rare classes, leading to unreliable performance estimates. Use stratified sampling when splitting data to ensure each fold maintains the overall class distribution.

Computational Considerations

The computational complexity depends primarily on the optimization algorithm and dataset size. For the lbfgs solver, each iteration requires computing the gradient and Hessian, which scales as O(n × p × K) where n is the number of observations, p is the number of features, and K is the number of classes. Training time depends on the number of iterations needed for convergence, which typically ranges from 10 to 100 iterations for well-conditioned problems. For datasets with fewer than 10,000 observations and a few dozen features, training typically completes in seconds on modern hardware. As datasets grow larger, consider using stochastic solvers like saga, which process data in mini-batches and can be more efficient for very large datasets (>100,000 observations).

Memory requirements are generally modest compared to other machine learning methods. The model stores (p+1) × (K-1) coefficients, which is typically small even for high-dimensional problems. During training, the optimization algorithm stores gradient and Hessian information, but this scales linearly with the number of parameters. For most applications, memory is not a limiting factor unless you have an extremely large number of features (>100,000) or classes (>1,000). When working with high-dimensional sparse data (such as text features), use sparse matrix representations to reduce memory usage and improve computational efficiency.

For deployment in production systems, multinomial logistic regression offers several advantages. Prediction is fast and deterministic, requiring only matrix multiplication followed by the softmax transformation, which scales as O(p × K) per observation. This makes the model suitable for real-time applications where low latency is important. The model is straightforward to serialize and deploy across different platforms, and predictions can be easily parallelized when scoring large batches of observations. When computational resources are limited, multinomial logistic regression can be a good choice compared to more complex models like neural networks or ensemble methods, particularly when the linear assumption is approximately satisfied.

Performance and Deployment Considerations

Evaluating model performance requires attention to multiple metrics beyond simple accuracy. The confusion matrix reveals which classes are being confused with each other, often suggesting feature engineering opportunities or class imbalance issues. Class-specific precision and recall provide insight into how well the model performs for each category, which is important when different types of errors have different costs. For example, in medical diagnosis, failing to identify a serious condition (low recall) may be more costly than occasionally flagging healthy patients for additional testing (low precision). The F1-score balances these concerns and provides a single metric that accounts for both precision and recall.

Log loss (cross-entropy) evaluates the quality of probability predictions, not just the final class assignments. A model with good accuracy but poor log loss may be overconfident in its predictions, which can be problematic when probability estimates are used for downstream decision-making. Calibration plots can help assess whether predicted probabilities match actual frequencies—well-calibrated models should predict 70% probability for events that occur 70% of the time. When deploying models that output probabilities, calibration is often as important as discrimination (the ability to separate classes). Consider using calibration methods like Platt scaling or isotonic regression if your model shows poor calibration on validation data.

For production deployment, establish monitoring procedures to detect when model performance degrades over time. Track key metrics like per-class accuracy, precision, and recall on incoming data, and set up alerts when these metrics fall below acceptable thresholds. Concept drift—where the relationship between features and the target changes over time—is a common issue in production systems. Retrain the model periodically on recent data to maintain performance, and consider implementing online learning approaches if the data distribution changes rapidly. When deploying updates, use A/B testing or shadow mode to validate that new models improve performance before fully replacing existing models. Document the model's limitations and the conditions under which it was trained to help prevent misuse in scenarios where the model may not be appropriate.

Summary

Multinomial logistic regression is a powerful and interpretable method for multi-class classification problems that extends the principles of binary logistic regression to handle three or more mutually exclusive categories. The model's foundation lies in the softmax function, which ensures that predicted probabilities are valid (non-negative and sum to one) while maintaining the linear relationship between predictors and log-odds that makes the model interpretable.

The key advantages of this approach include its probabilistic output, which provides confidence estimates for predictions, its natural handling of the probability constraint that all classes sum to one, and its interpretability through odds ratios. However, practitioners should be aware of its limitations, particularly the independence of irrelevant alternatives assumption and its sensitivity to the choice of reference category.

The model is particularly well-suited for applications where interpretability is important, such as healthcare diagnosis, marketing segmentation, and any domain where understanding the relationship between predictors and outcomes is as valuable as making accurate predictions. With proper data preprocessing, careful model validation, and attention to its assumptions, multinomial logistic regression provides a robust foundation for multi-class classification problems across many practical applications.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding of multinomial logistic regression? Take this quiz to reinforce what you've learned about multi-class classification.

Comments