Learn to evaluate instruction-tuned LLMs using benchmarks like Alpaca Eval and MT-Bench, human evaluation protocols, and LLM-as-Judge automatic methods.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Instruction Following Evaluation

Training an instruction-tuned model is only half the battle. The other half, equally important, is determining whether your model actually follows instructions well. Unlike traditional NLP tasks where we can compute precision, recall, or BLEU scores against reference outputs, instruction following presents a fundamental evaluation challenge: for most instructions, there is no single correct answer.

Consider the instruction "Write a poem about autumn." A good response could take countless forms, from haiku to sonnet, melancholic to celebratory. Traditional metrics like exact match or BLEU score, which we might use for tasks like machine translation, become nearly meaningless here. The same challenge applies to instructions like "Explain quantum entanglement to a five-year-old" or "List pros and cons of remote work." Each admits many valid, high-quality responses.

This chapter explores how we evaluate instruction-following capabilities. We'll examine purpose-built benchmarks, contrast human evaluation approaches with automatic metrics, and investigate what makes some instructions harder than others. These evaluation methods directly inform the training decisions we discussed in the previous chapter on instruction tuning training, and they become even more critical when we move to alignment with human preferences in the upcoming Part on RLHF.

Benchmarks for Instruction Following

Evaluating instruction-tuned models requires benchmarks that capture the breadth of tasks you actually care about. The challenge is creating evaluation frameworks that reflect real-world usage and produce actionable measurements. Early evaluation relied heavily on existing NLP benchmarks, but the field has developed specialized benchmarks that better reflect real-world instruction following. Understanding the landscape of available benchmarks, and the unique strengths and limitations of each, is essential for you when developing or deploying instruction-tuned models.

Standard NLP Benchmarks

Before instruction-specific benchmarks emerged, we evaluated instruction-tuned models on established benchmarks. While these don't directly measure instruction following, they provide useful baselines for comparing model capabilities. The reasoning behind using these traditional benchmarks is straightforward: if a model cannot demonstrate strong performance on well-defined tasks with clear correct answers, we have little reason to expect it will handle the more ambiguous challenge of open-ended instruction following.

MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) tests knowledge across 57 subjects from elementary mathematics to professional law. Questions are multiple-choice, making evaluation straightforward. The breadth of MMLU's subject coverage makes it particularly valuable for assessing whether a model has acquired broad factual knowledge during training, which forms a foundation for responding helpfully to diverse requests from you:

This formatting is critical for evaluation. By structuring the task as a prompt, we can parse the model's next token (e.g., "C") to determine accuracy. Evaluating instruction-tuned models requires translating structured tasks into natural language prompts that match how you interact with the model. This translation step itself introduces variability: different prompt phrasings can yield different accuracy scores, highlighting the sensitivity of instruction-tuned models to precise wording.

HellaSwag tests commonsense reasoning through sentence completion, while TruthfulQA evaluates whether models generate truthful answers rather than plausible-sounding falsehoods. These benchmarks tell us about model capabilities but don't directly measure whether a model follows your arbitrary instructions. The distinction matters because a model might possess extensive knowledge (scoring well on MMLU) and strong reasoning abilities (performing well on HellaSwag) yet still struggle to understand what you actually want when you phrase requests in natural, conversational language.

Instruction-Specific Benchmarks

The field has developed benchmarks specifically designed to evaluate instruction following. These focus on the quality of responses to diverse, open-ended instructions. We develop specialized benchmarks because instruction following requires more than just knowledge retrieval or logical reasoning. It requires understanding your intent, adapting tone and format appropriately, and maintaining coherence across complex, multi-faceted requests.

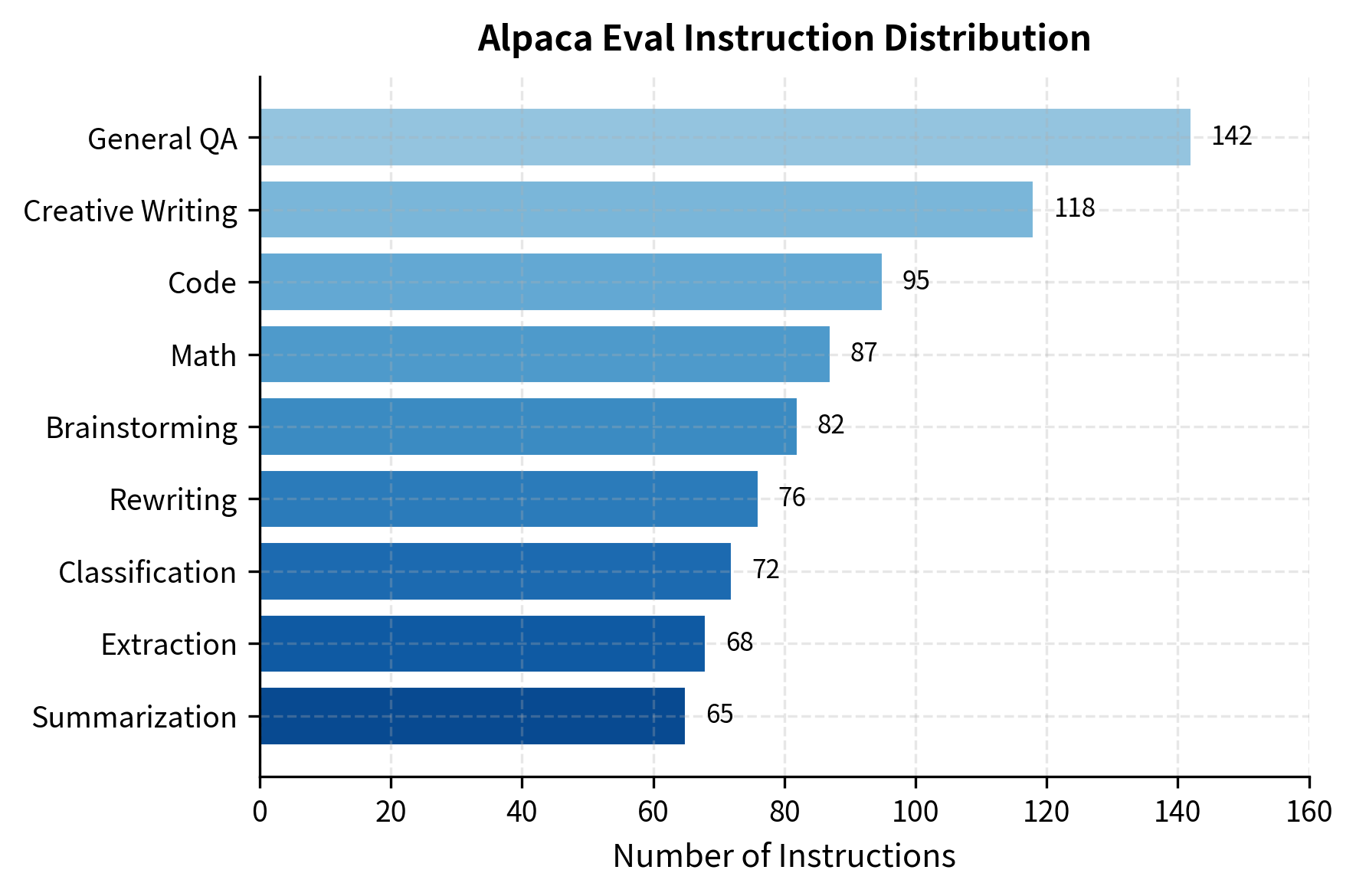

Alpaca Eval contains 805 instructions covering a range of tasks. The key innovation is using an automatic evaluator (typically GPT-4) to compare model outputs against a reference model's outputs. This approach addresses the scalability problem inherent in human evaluation while still producing preference-based rankings that correlate reasonably well with human judgments:

These categories illustrate the shift from narrow tasks to broad capabilities. The model must handle creative writing, logic, and extraction within a single interface. What makes this benchmark particularly valuable is its recognition that you do not restrict yourself to a single task type. A model deployed as a general assistant must seamlessly transition between generating creative content, performing analytical tasks, and answering factual questions, often within a single conversation session.

MT-Bench (Multi-Turn Benchmark) evaluates models on 80 multi-turn conversations across 8 categories: writing, roleplay, reasoning, math, coding, extraction, STEM, and humanities. The multi-turn aspect is crucial because your conversations require maintaining context. This benchmark addresses a critical gap in single-turn evaluations: the ability to build coherently on previous exchanges, remember earlier constraints, and integrate new information without contradicting prior responses:

The second turn tests whether the model can build on its previous response while integrating new constraints. This design reflects how humans actually use conversational AI systems: they start with an initial request, then refine or extend it based on the model's response. A model that excels at isolated single-turn responses but fails to maintain coherence across multiple turns will frustrate you when you expect the kind of continuous understanding that characterizes human conversation.

LMSYS Chatbot Arena takes a different approach: you compare model outputs head-to-head without knowing which model produced which response. This crowdsourced evaluation provides authentic preference data but is slow and expensive to collect. The strength of this approach is that it reflects real-world usage. Rather than relying on predetermined instructions that may not reflect your actual needs, Arena captures genuine queries from you and preferences in a natural setting.

Benchmark Limitations

No benchmark perfectly captures instruction-following ability. Standard benchmarks like MMLU test knowledge but not the ability to follow arbitrary formatting requests. Instruction benchmarks like Alpaca Eval depend heavily on the automatic evaluator's biases. Arena-style benchmarks reflect your preferences but may favor verbosity or stylistic flourishes over correctness.

A robust evaluation strategy uses multiple benchmarks, combining automatic metrics for rapid iteration with periodic human evaluation for ground truth.

Human Evaluation

Human evaluation remains the gold standard for assessing instruction following. When we want to know if a model's response is helpful, accurate, and appropriate, asking humans provides the most direct answer. If we want to build models that satisfy you, your judgment is the ultimate measure of success. However, human evaluation introduces its own complexities that you must understand and navigate carefully.

Pairwise Comparison

The most common human evaluation protocol presents evaluators with two responses to the same instruction and asks them to select the better one. This approach leverages a fundamental insight from psychology: humans are significantly better at making relative comparisons than absolute judgments. When asked to rate a response on a 1-10 scale, different evaluators may have wildly different internal calibrations. But when asked which of two responses is better, they tend to agree more consistently:

In this example, Response A provides a scientific explanation, while Response B uses an intuitive analogy. The "better" response depends on your intent, highlighting the subjectivity of the task. If the instruction had specified "explain to a child," most evaluators would prefer Response B. Without that specification, different evaluators may legitimately reach different conclusions based on their assumptions about the target audience.

Pairwise comparison has several advantages. It's cognitively easier than assigning absolute scores because humans are better at relative judgments. It also directly measures what we care about: which model produces more preferred outputs. Additionally, pairwise comparisons naturally aggregate into preference rankings that can inform training through methods like RLHF, creating a direct connection between evaluation methodology and model improvement.

Rating Scales

Alternative approaches use rating scales where evaluators score individual responses. This method offers different tradeoffs: while potentially less reliable at the individual judgment level, it provides richer information about specific dimensions of quality:

Rating scales enable more granular feedback and can identify specific weaknesses. For instance, a model might consistently score high on helpfulness but low on accuracy, revealing that it generates plausible-sounding but incorrect information. This diagnostic capability makes rating scales particularly valuable during model development, where understanding the nature of failures is as important as measuring overall quality. However, they suffer from calibration issues: different evaluators may interpret "4 out of 5" differently, and even individual evaluators may shift their standards over the course of a long evaluation session.

Inter-Annotator Agreement

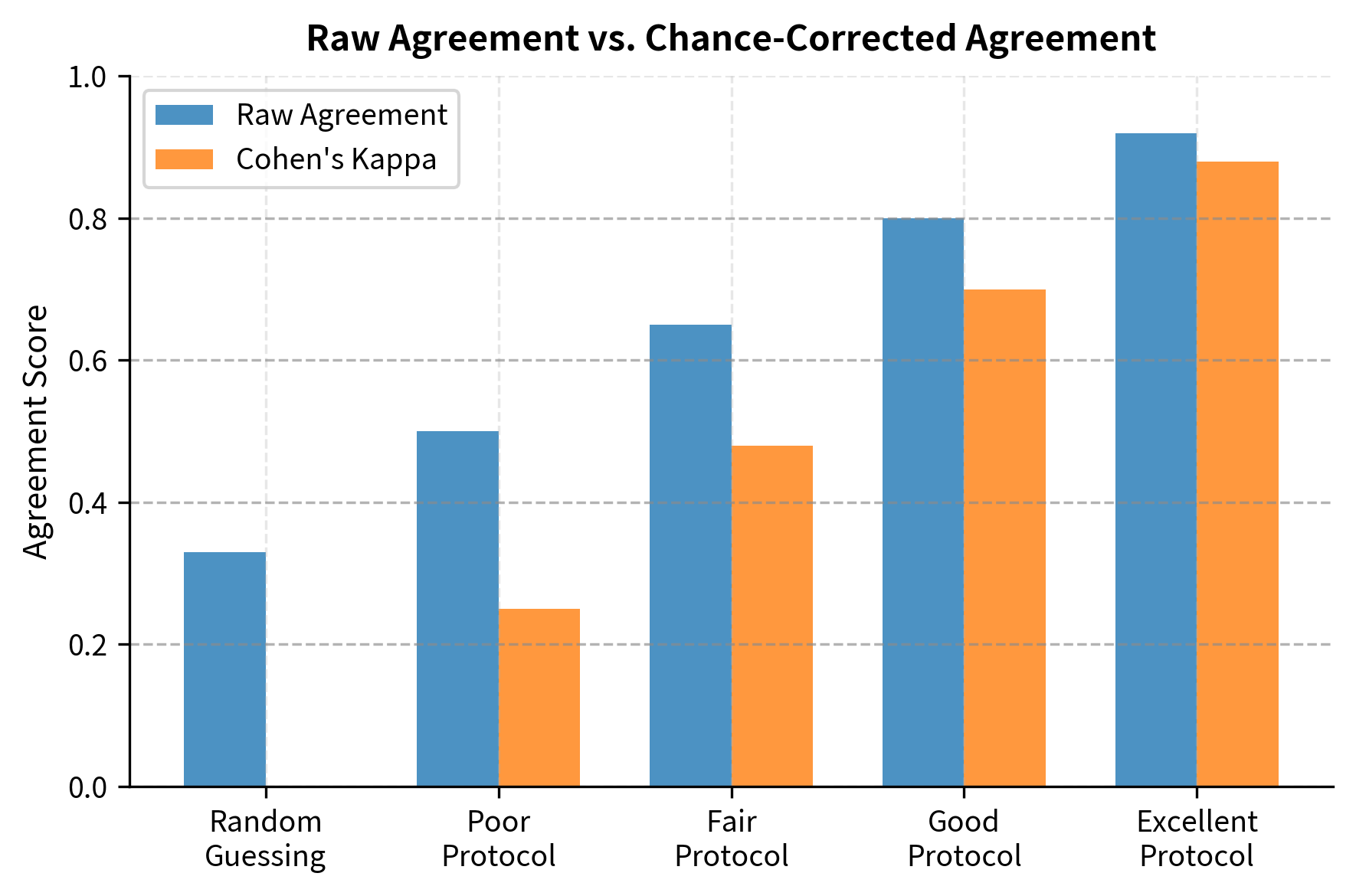

A critical concern in human evaluation is whether different evaluators agree. We measure this using inter-annotator agreement metrics. Agreement measurement is important because it clarifies whose judgment to trust when evaluators disagree. High agreement suggests that quality differences between responses are clear and objective. Low agreement indicates either that the responses are genuinely comparable in quality, that the evaluation criteria are ambiguous, or that the task itself admits multiple valid interpretations:

Cohen's Kappa accounts for agreement that would occur by chance. This correction is essential because raw agreement can be misleading. If one response is clearly better 90% of the time and evaluators simply choose randomly, they would still agree 50% of the time by chance alone. Kappa provides a more honest assessment by asking: how much better is the observed agreement than what we would expect from random guessing? In the example above, two raters agreed on 80% of cases, and Kappa shows this represents substantial agreement after adjusting for chance.

Challenges in Human Evaluation

Human evaluation faces several practical challenges:

Cost and scale. Evaluating thousands of examples across multiple models quickly becomes expensive. A single evaluation comparing two models on 1000 instructions with 3 annotators per comparison requires 3000 human judgments.

Evaluator expertise. For technical instructions (code, math, science), evaluators need domain expertise to judge correctness. A non-programmer might prefer a plausible-looking but buggy code response over a correct but terse one.

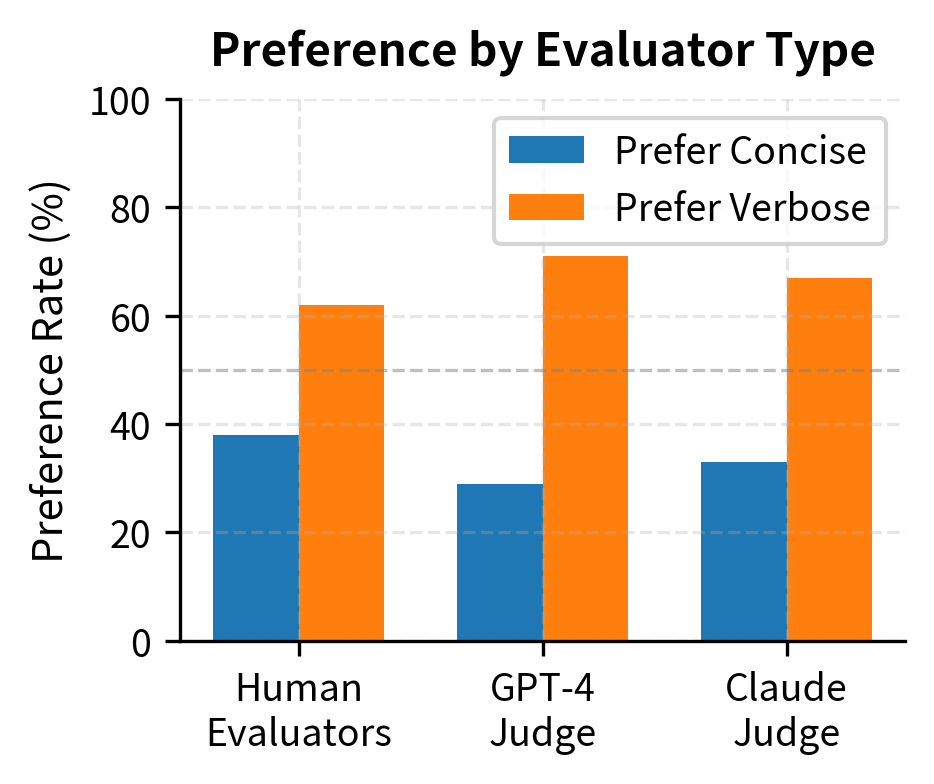

Evaluation bias. Humans tend to prefer longer, more detailed responses even when brevity is appropriate. They may also favor responses that match their pre-existing beliefs, regardless of factual accuracy.

Cognitive load. Comparing long, complex responses is mentally taxing. Evaluator fatigue leads to inconsistent judgments, especially in later evaluation sessions.

These challenges motivate the development of automatic evaluation methods that can scale while approximating human judgment.

Automatic Evaluation

Automatic evaluation methods enable rapid iteration during model development. Automatic evaluation is useful because it removes human annotation bottlenecks and provides fast, reproducible measurements. The most successful approach treats evaluation itself as a language modeling task, using powerful LLMs to judge response quality. This reflects a trend where models become tools for training and evaluating other models.

LLM-as-a-Judge

The LLM-as-a-Judge paradigm uses a capable language model (typically GPT-4 or a similar model) to evaluate responses. This approach assumes that if a model can generate high-quality responses, it can also recognize quality in the responses of other models. This mirrors how human expertise works: skilled writers can identify good writing, experienced programmers can spot elegant code, and domain experts can assess the accuracy of technical explanations:

The structured prompt forces the judge to break down the evaluation into specific criteria before declaring a winner, which improves consistency compared to asking for a simple score. This structure serves multiple purposes: it guides the judge toward comprehensive evaluation rather than snap judgments, it provides interpretable reasoning that can be audited for systematic errors, and it aligns the evaluation process with the multi-faceted nature of response quality.

Research shows that GPT-4 as a judge achieves 80%+ agreement with human preferences on many instruction-following tasks. However, this approach has known biases that you must account for in your evaluation designs.

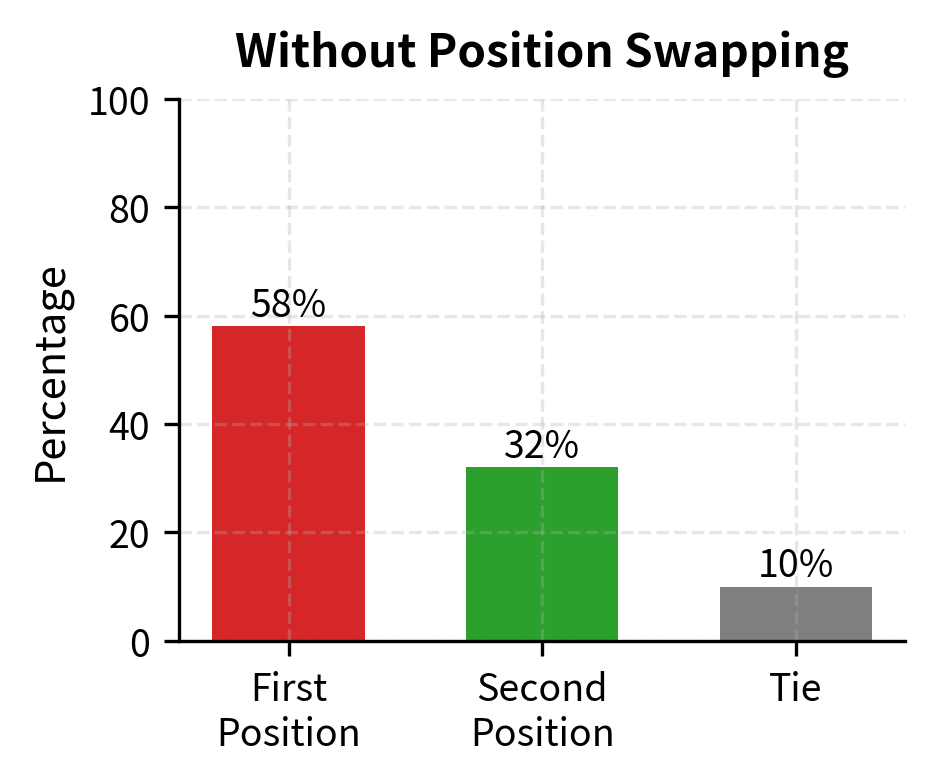

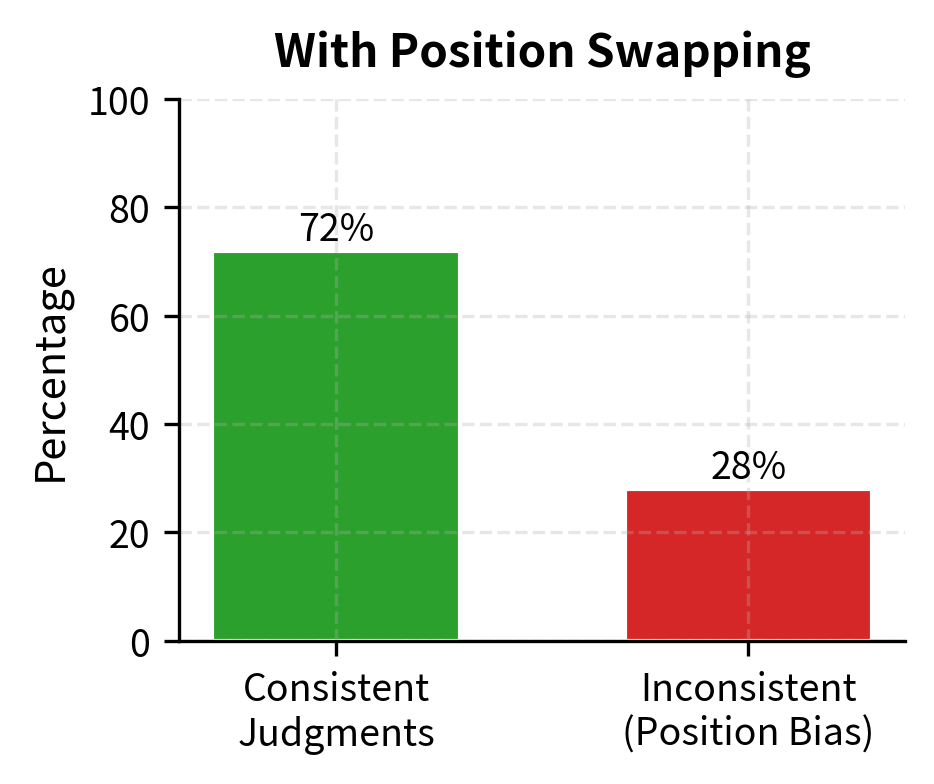

Position Bias and Mitigation

LLM judges exhibit position bias: they tend to favor the response presented first (or sometimes second, depending on the model). This bias likely emerges from patterns in the training data, where examples presented earlier in a list or conversation may have been systematically different from later examples. Regardless of its origin, position bias represents a significant confound that can distort evaluation results. We can mitigate this by evaluating each pair twice with swapped positions:

When results conflict between position orderings, declaring a tie is conservative but honest. The inconsistency itself reveals uncertainty in the evaluation. This approach doubles the computational cost of evaluation but provides a crucial quality check. The rate of inconsistent judgments also serves as a diagnostic: if position swapping frequently changes the outcome, it suggests either that the responses are genuinely similar in quality or that the judge model is unreliable for this type of instruction.

Verbosity Bias

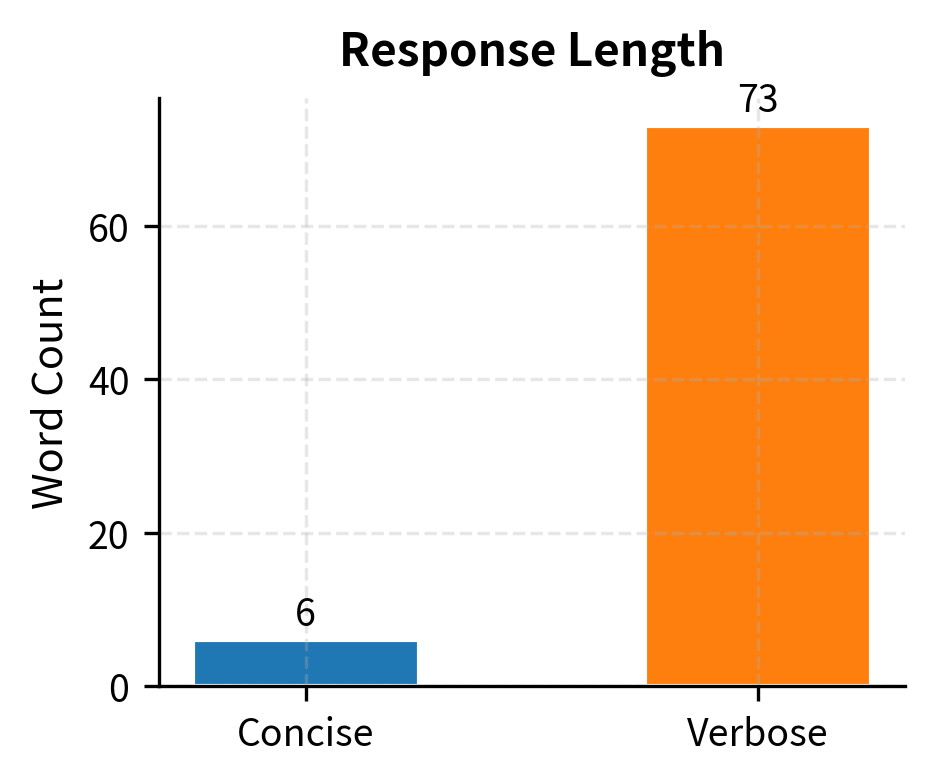

LLM judges also exhibit verbosity bias, preferring longer responses even when they contain unnecessary repetition or padding. This bias reflects a tendency to conflate quantity with quality, a pattern that likely exists in both human preferences and training data. Understanding this bias is crucial because it can systematically favor models that generate verbose outputs over those that provide concise, direct answers:

Both responses are factually correct, but LLM judges (and humans) often prefer the verbose version despite the concise one being more direct. This "length bias" often mistakes verbosity for quality. The verbose response includes tangentially related information that, while accurate, does not address your question more effectively. In fact, if you simply needed a quick factual answer, the verbose response wastes time and may obscure the key information you sought.

To mitigate verbosity bias, some evaluation protocols explicitly instruct the judge to prefer concise responses when both are equally correct. Others use length-controlled comparisons or normalize scores by response length. A more sophisticated approach involves asking judges to evaluate whether each piece of information in a response directly contributes to answering your question, penalizing padding and tangents explicitly.

Win Rate Calculation

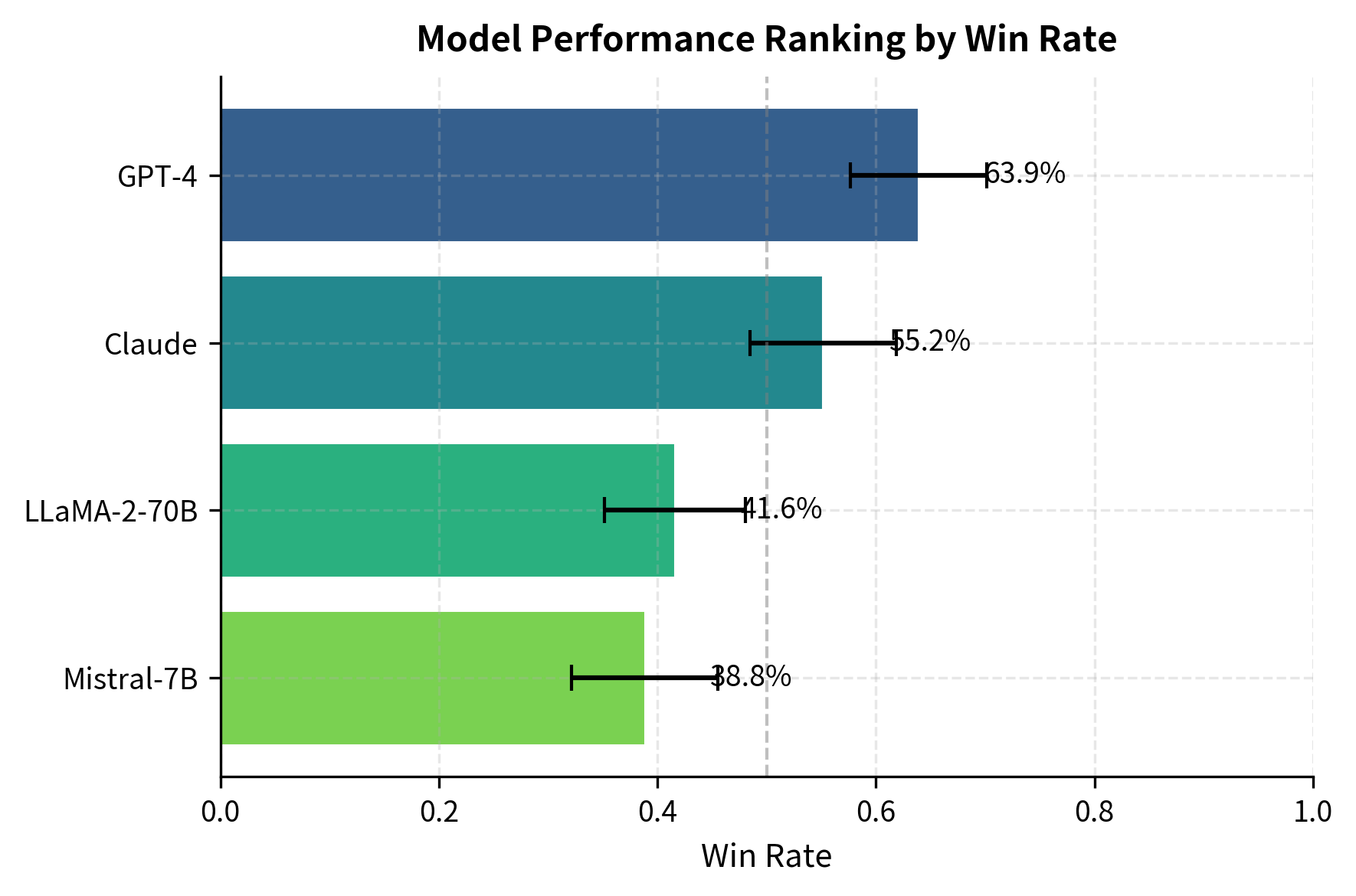

After collecting pairwise judgments, we calculate win rates to compare models. Win rates summarize performance by showing the fraction of comparisons a model wins against its opponents. This metric directly answers the question, "How often would you prefer this model's output over alternatives?":

The results show a clear ranking based on head-to-head performance. Win rates provide a simple summary, but they don't account for which opponents each model faced. A model that only competed against weak opponents would have an inflated win rate compared to one that faced stronger competition. More sophisticated ranking systems like Elo or Bradley-Terry (which we'll explore in the upcoming chapter on preference modeling) provide better rankings when not all pairs are equally compared. These systems model each comparison as evidence about underlying model strength, accounting for the difficulty of each opponent faced.

Reference-Based Metrics

For some instruction types, reference-based metrics remain useful. Code generation tasks can be evaluated by running tests. This represents a fundamentally different evaluation paradigm: rather than asking whether a response seems good, we verify whether it actually works. This functional evaluation provides an objective ground truth that neither human evaluators nor LLM judges can achieve for tasks with verifiable outputs:

With a 100% pass rate, we can confirm the model's solution is functionally correct. For tasks with verifiable outputs (math problems, factual questions, code), combining functional tests with qualitative LLM-as-judge evaluation provides comprehensive assessment. The functional tests verify correctness while qualitative evaluation assesses aspects like code readability, efficiency, and adherence to best practices that are not captured by pass/fail test results alone.

Instruction Difficulty

Not all instructions are equally challenging. Understanding what makes instructions difficult helps us build better training sets and evaluate models more thoroughly. A comprehensive evaluation should include instructions spanning the full range of difficulty to identify where models excel and where they struggle. This understanding also informs curriculum design during training, as exposing models to appropriately challenging examples improves learning efficiency.

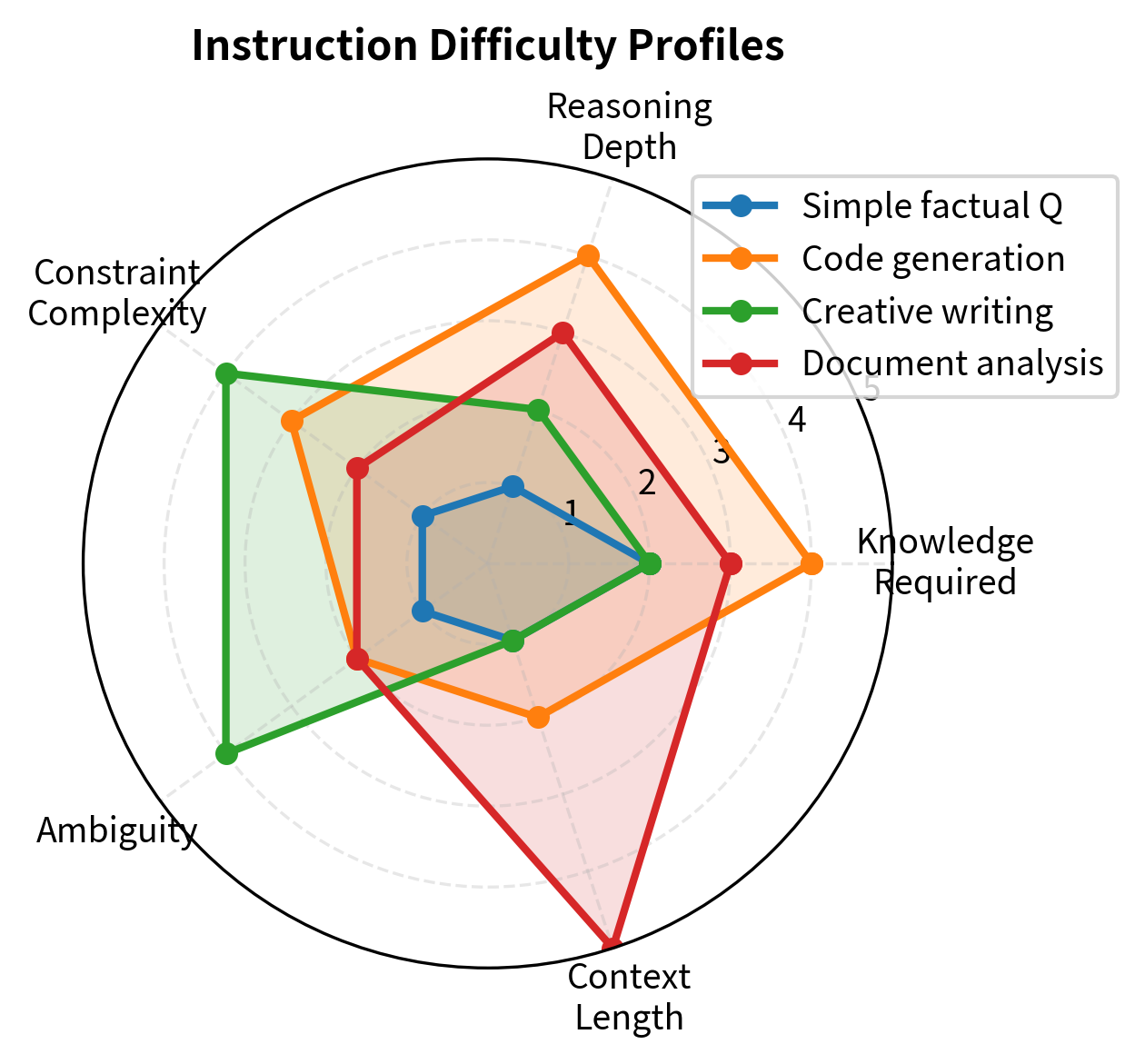

Dimensions of Difficulty

Instruction difficulty emerges from several independent dimensions. These dimensions are largely orthogonal, meaning an instruction can be easy along one dimension while being extremely challenging along another. A simple factual question might require specialized domain knowledge, while a complex multi-step task might involve only common knowledge. Understanding these dimensions helps us construct balanced evaluation sets that probe different aspects of model capability:

A comprehensive evaluation should sample across all difficulty dimensions, not just one. A model might handle high-knowledge-requirement questions well because it memorized relevant facts during pretraining, but fail on multi-step reasoning despite the individual steps being simple. Conversely, a model with strong reasoning capabilities might produce excellent responses to complex logical puzzles while making basic factual errors on domain-specific questions.

The IFEval Benchmark

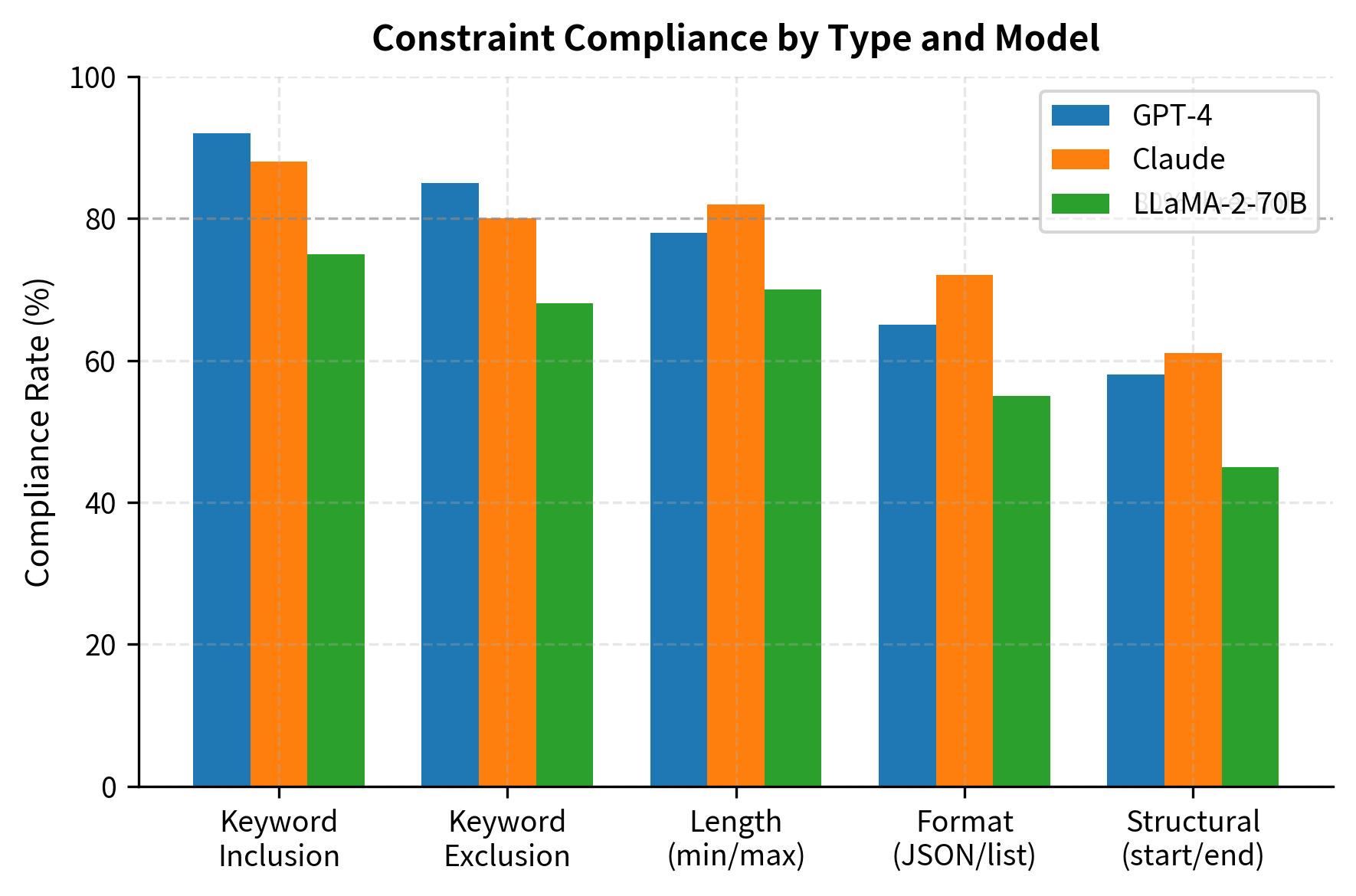

IFEval (Instruction Following Evaluation) specifically measures whether models follow explicit constraints. Unlike open-ended benchmarks, IFEval instructions contain verifiable requirements. This design philosophy reflects an important insight: while overall response quality is subjective and difficult to measure, constraint compliance is objective and automatically verifiable. A response either contains exactly 100 words or it does not; it either includes the required keyword or it does not. This objectivity enables large-scale automatic evaluation without the biases inherent in LLM-as-judge approaches:

IFEval's constraints are automatically verifiable, enabling fully automatic evaluation. The verification process requires no subjective judgment: we simply check whether each constraint is satisfied according to its precise definition:

IFEval enables measuring instruction-following ability independent of response quality. A model might generate excellent prose but fail basic formatting requirements, revealing a gap in instruction compliance. This separation is valuable diagnostically: it distinguishes between models that understand what to do but generate poor content versus models that generate good content but fail to follow explicit directions. Both failure modes exist in practice, and they require different interventions to address.

Difficulty Scoring

We can estimate instruction difficulty before evaluation by analyzing instruction characteristics. This heuristic approach enables automatic categorization of instructions, which is useful for ensuring evaluation sets include appropriate coverage across difficulty levels. While no heuristic can perfectly predict how challenging an instruction will be for a given model, analyzing structural features provides a reasonable approximation:

While heuristic, difficulty estimation helps balance evaluation sets and identify where models struggle. By tracking performance across difficulty levels, we can characterize model capabilities more precisely. A model that excels on easy instructions but fails on difficult ones differs meaningfully from a model with consistent performance across difficulty levels, even if their average scores are similar.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Evaluating instruction following remains an open problem with no perfect solution. Understanding the limitations of each approach helps you make better evaluation decisions.

Human evaluation, despite being the gold standard, faces fundamental challenges beyond cost. Evaluators disagree on what constitutes a "good" response, and this disagreement isn't noise; it reflects genuine differences in preferences. Some of you prefer concise answers while others want comprehensive explanations. Some prioritize strict factual accuracy while others value engaging presentation. A model that scores highly with one evaluator population may score poorly with another. This makes it difficult to declare any single model universally "best" at instruction following.

Automatic evaluation using LLM-as-judge introduces its own systematic biases. Beyond position and verbosity bias, these systems tend to favor responses that match their own training distribution. A GPT-4 judge may prefer GPT-4-style responses, creating evaluation circularity when developing models trained to match GPT-4 outputs. Additionally, LLM judges struggle with certain evaluations: they often cannot reliably verify factual claims, execute code mentally, or assess whether a creative writing piece is genuinely original versus derivative. For high-stakes evaluations, automatic metrics should complement, not replace, targeted human review.

Benchmark saturation presents an emerging challenge. As models improve and benchmarks become well-known, performance gains may reflect benchmark-specific optimization rather than genuine capability improvements. Models trained with MMLU-style questions in their data will naturally score higher on MMLU, even if they don't have stronger reasoning abilities overall. This motivates continuous development of new evaluation paradigms and held-out test sets that cannot be gamed through data contamination.

The gap between benchmark performance and real-world usefulness is perhaps the most significant limitation. A model might achieve high scores on instruction-following benchmarks while still frustrating you in deployment. Benchmarks test specific, curated instructions, but you issue ambiguous, poorly-formed, or contextually-dependent requests. Evaluation should ultimately connect to your satisfaction metrics when possible, treating benchmarks as proxies rather than ground truth.

Summary

Evaluating instruction-following models requires multiple complementary approaches because no single metric captures all aspects of quality.

Benchmarks like Alpaca Eval, MT-Bench, and IFEval provide standardized comparisons across models. Standard NLP benchmarks test underlying capabilities, while instruction-specific benchmarks measure actual response quality and constraint compliance.

Human evaluation remains the gold standard but faces challenges of cost, scale, and inter-annotator disagreement. Pairwise comparison tends to be more reliable than absolute rating scales. Measuring agreement using metrics like Cohen's Kappa helps assess evaluation reliability.

Automatic evaluation using LLM-as-judge scales effectively but introduces systematic biases including position bias and verbosity bias. Position swapping and explicit instruction to judges can partially mitigate these issues. For verifiable tasks like code generation, functional testing provides ground truth that complements qualitative evaluation.

Instruction difficulty varies across multiple dimensions: knowledge requirements, reasoning depth, constraint complexity, ambiguity, and context length. IFEval specifically measures constraint compliance through automatically verifiable requirements, separating instruction-following ability from response quality.

The evaluation methods covered here directly inform the next part on RLHF, where preference data collected through these evaluation approaches becomes training signal for aligning models with human values. Understanding both the power and limitations of instruction-following evaluation helps you make informed decisions about model selection and deployment.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about instruction following evaluation.

Comments