Learn time-series and cross-sectional momentum strategies. Implement moving average crossovers, breakout systems, and CTA approaches with Python code.

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Trend Following and Momentum Strategies

In the previous chapter, we explored mean reversion strategies that profit when prices deviate from equilibrium and subsequently return to historical norms. Momentum strategies take the opposite philosophical stance: rather than betting against recent price movements, you bet that winning assets will continue winning and losing assets will continue losing. This seemingly simple idea, that "the trend is your friend," has generated consistent profits across asset classes and time periods, presenting one of the most persistent anomalies in finance.

Momentum is not a single strategy but a family of approaches that exploit the tendency of asset prices to exhibit persistence. The two primary variants are time-series momentum, which compares an asset's current price to its own historical prices, and cross-sectional momentum, which ranks assets relative to their peers. Time-series momentum forms the foundation of Commodity Trading Advisor (CTA) strategies that trade futures across global markets, while cross-sectional momentum underlies many equity long-short strategies. Both variants share common behavioral roots in investor psychology but differ substantially in implementation and risk characteristics.

The persistence of momentum returns poses a challenge to the efficient market hypothesis we discussed in Part IV. If markets efficiently incorporate all available information, why should past returns predict future returns? The answer likely involves a combination of behavioral biases such as investor underreaction to new information, structural frictions that prevent immediate arbitrage, and compensation for bearing crash risk. Understanding these sources helps you design more robust momentum strategies and anticipate when they might fail.

Time-Series Momentum and Trend Following

Time-series momentum, also called absolute momentum or trend following, generates signals based on an asset's own historical performance rather than comparing it to other assets. The core premise is straightforward: if an asset has been rising, go long; if it has been falling, go short or stay out. This approach has been implemented by trend-following hedge funds and CTAs for decades, with documented profitability extending back over a century.

The Mathematical Foundation

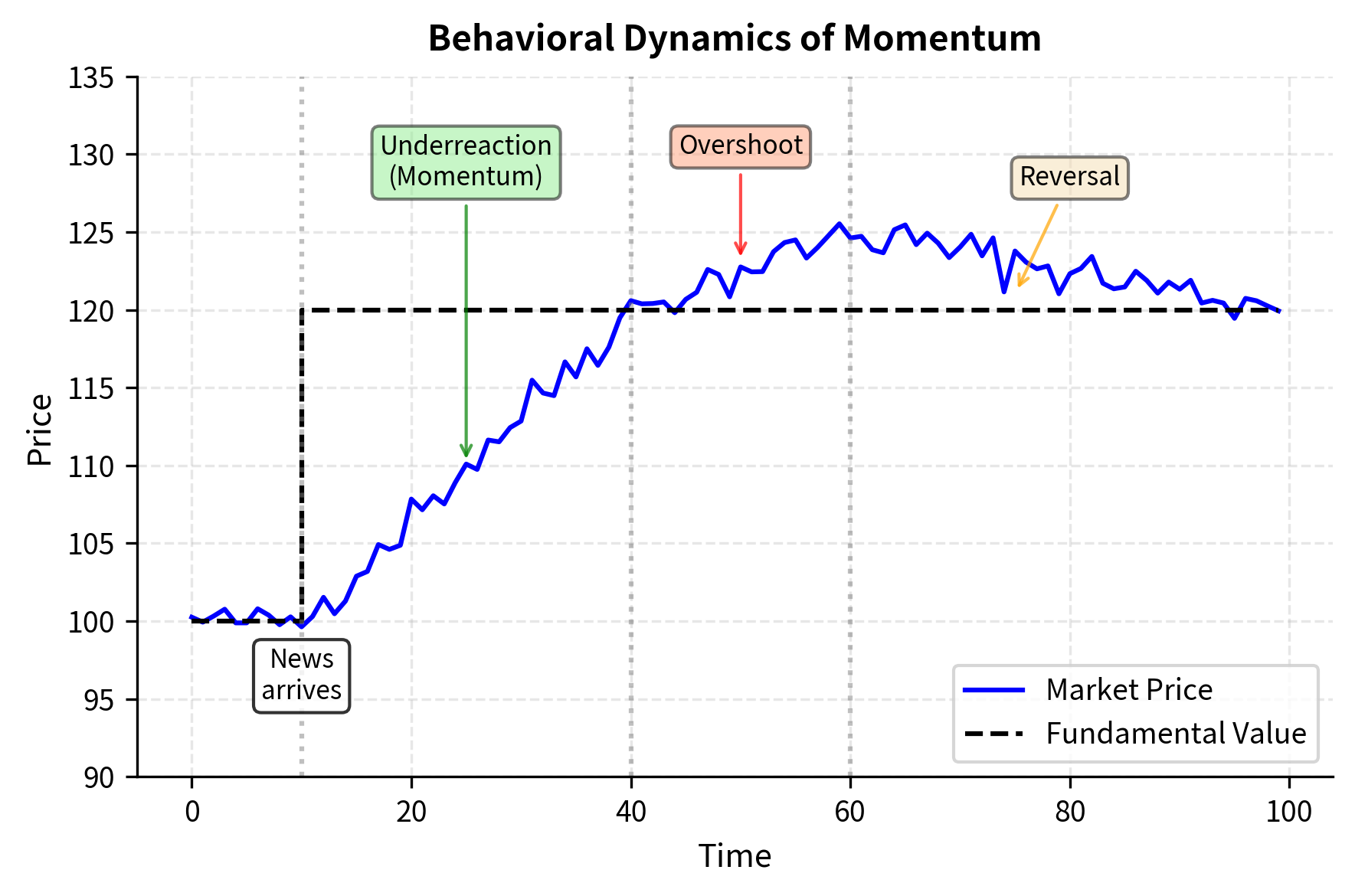

The foundation of time-series momentum rests on a deceptively simple observation: recent price direction tends to persist. Before we formalize this intuition, consider why such persistence might exist. When new information enters the market, perhaps an unexpected earnings surprise or a shift in monetary policy, prices do not instantly jump to their new equilibrium value. Instead, the adjustment unfolds gradually as different market participants learn about, interpret, and act upon the news. This gradual adjustment creates a window during which prices exhibit directional persistence, and momentum strategies seek to profit from this window.

The simplest time-series momentum signal compares an asset's current price to its price periods ago. This comparison answers a fundamental question: has the asset been trending upward or downward over the recent past? If we denote the price at time as , the momentum signal is:

where:

- : price of the asset at time

- : price of the asset periods ago

- : cumulative return over the lookback period

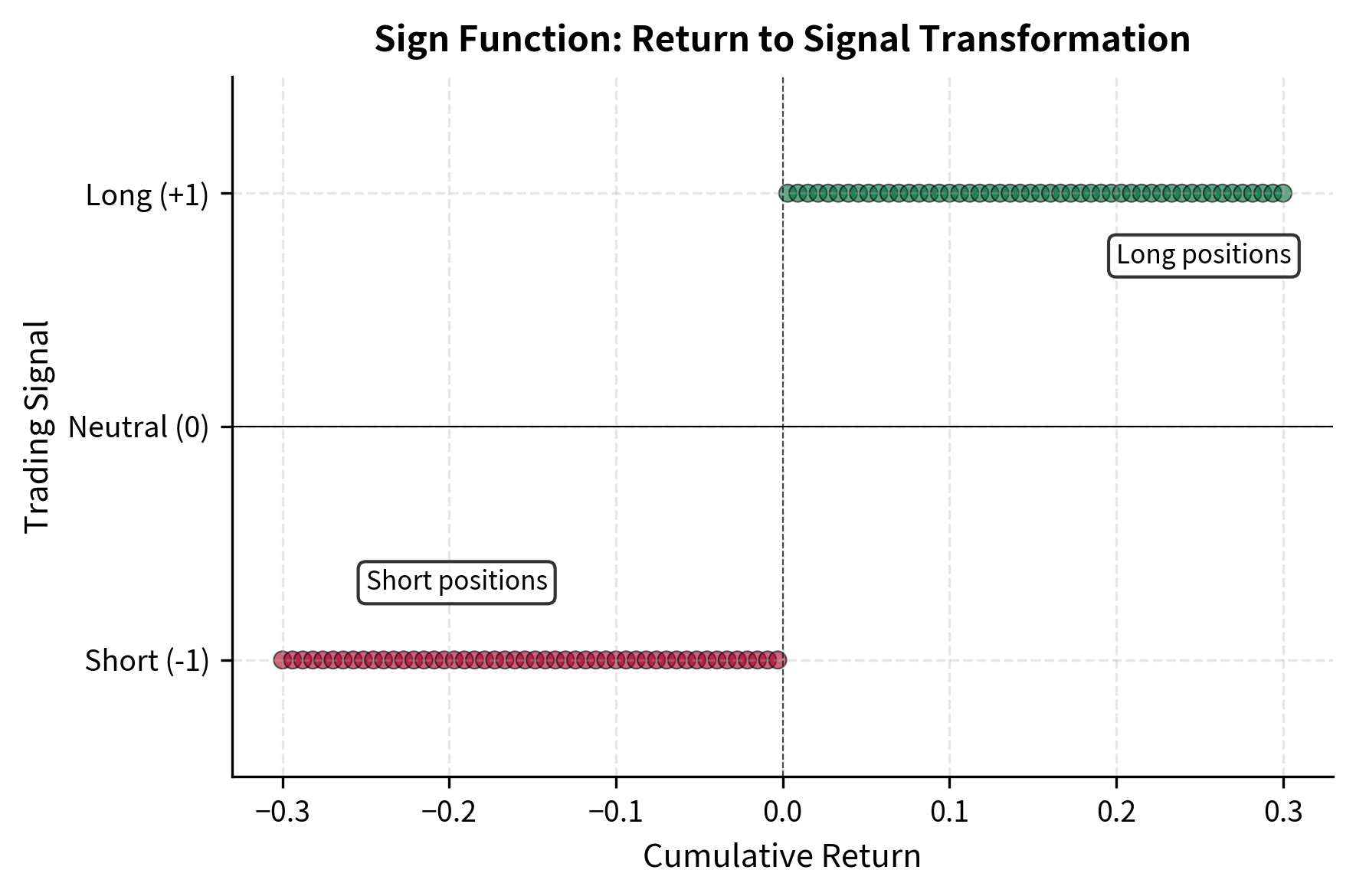

- : function returning if positive, if negative, and if zero

The sign function transforms the continuous return into a discrete trading signal. A positive signal indicates a long position, while a negative signal indicates a short position. This binary transformation reflects the core philosophy of trend following: we care primarily about the direction of the trend rather than its magnitude. A stock that rose 5% over the past year receives the same long signal as one that rose 50%, because both have demonstrated positive momentum.

In practice, however, raw price comparisons can generate noisy signals that whipsaw between long and short positions during sideways markets. You often use moving averages to smooth noise and generate more stable signals. The smoothing process filters out short-term fluctuations while preserving the underlying trend direction. The dual moving average crossover represents one of the most popular implementations, comparing a fast moving average with a short lookback period to a slow moving average with a longer lookback period:

where:

- : moving average value with a short lookback period

- : moving average value with a long lookback period

- : function returning if positive, if negative, and otherwise

The intuition behind this signal is elegant: the fast moving average represents recent price momentum, while the slow moving average represents the longer-term price equilibrium. When the fast average crosses above the slow average, it suggests that short-term momentum has turned positive relative to the longer-term baseline. This crossover often signals a shift in market sentiment or a fundamental change in the asset's supply and demand dynamics. Conversely, when the fast average crosses below the slow average, it indicates deteriorating short-term momentum and suggests the trend may be reversing.

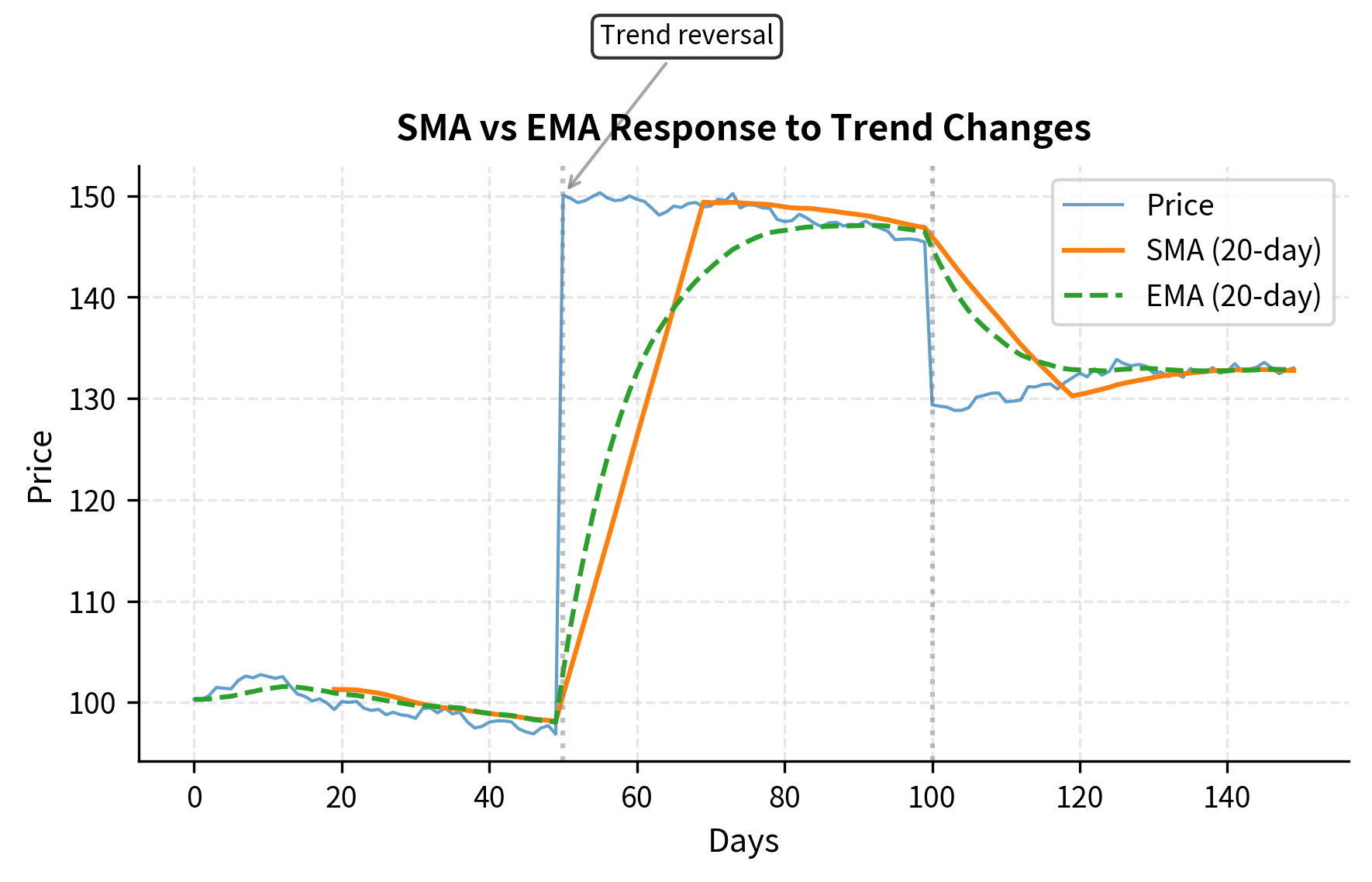

The simple moving average (SMA) calculates the arithmetic mean of prices over a lookback window , treating each observation within the window equally:

where:

- : simple moving average at time with lookback

- : asset price at lag

- : number of periods in the moving average window

By weighting all prices in the window equally with coefficient , this formula filters out high-frequency noise but introduces a deliberate lag. The average reacts more slowly to new price changes compared to the raw price series because each new observation only contributes of the total average value. This lag represents a tradeoff inherent in all smoothing techniques: greater noise reduction comes at the cost of slower signal response. For a 50-day moving average, today's price contributes only 2% of the average value, meaning the average responds gradually to even substantial price movements.

While simple moving averages provide effective smoothing, you might prefer alternatives that give more weight to recent observations. Exponential moving averages (EMAs) provide such an alternative, assigning exponentially decaying weights to historical prices:

where:

- : smoothing factor, typically calculated as

- : effective span or lookback period

- : current asset price

- : value of the exponential moving average in the previous period

This recursive formulation reveals the elegant structure of the EMA. The formula updates the average by combining two components: the new information representing today's price contribution, and the accumulated history carrying forward the weighted sum of all previous prices. The smoothing factor determines the relative importance of new versus old information. A larger value creates a more responsive average that tracks price changes closely, while a smaller produces a smoother average that emphasizes historical prices. The exponential weighting scheme assigns geometrically declining weights to older observations, so the average maintains a fading memory of the entire price series while remaining more responsive to recent trend changes than a simple moving average of equivalent span.

Implementing Moving Average Crossovers

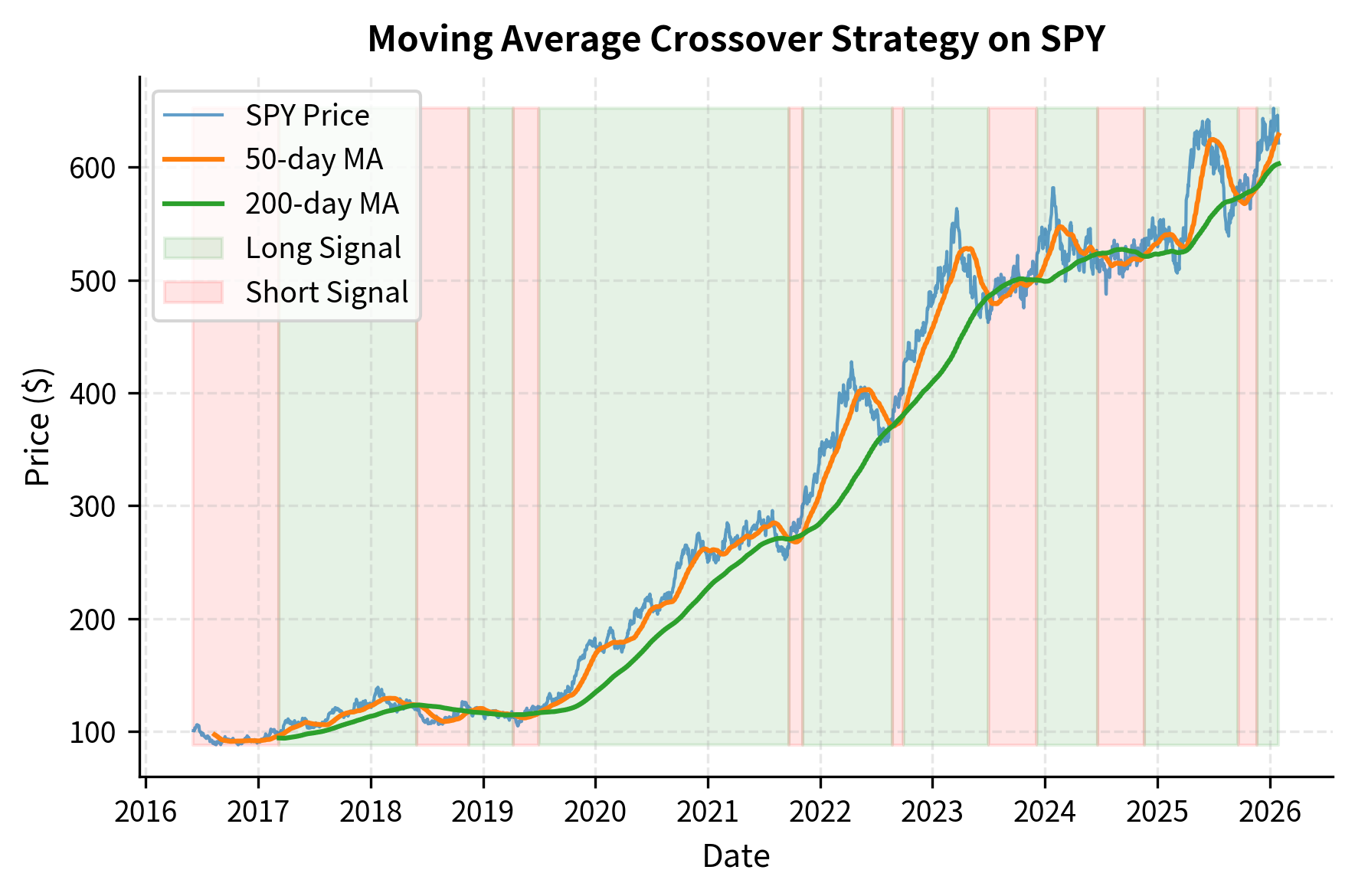

Let's implement a dual moving average crossover strategy on equity index data. We'll use a 50-day fast moving average and a 200-day slow moving average, a popular combination known as the golden cross (when fast crosses above slow) and death cross (when fast crosses below slow).

The shaded regions reveal how the strategy positions itself during different market regimes. During sustained uptrends, the fast moving average stays above the slow, keeping the strategy long. During corrections, the crossover generates a short or flat signal.

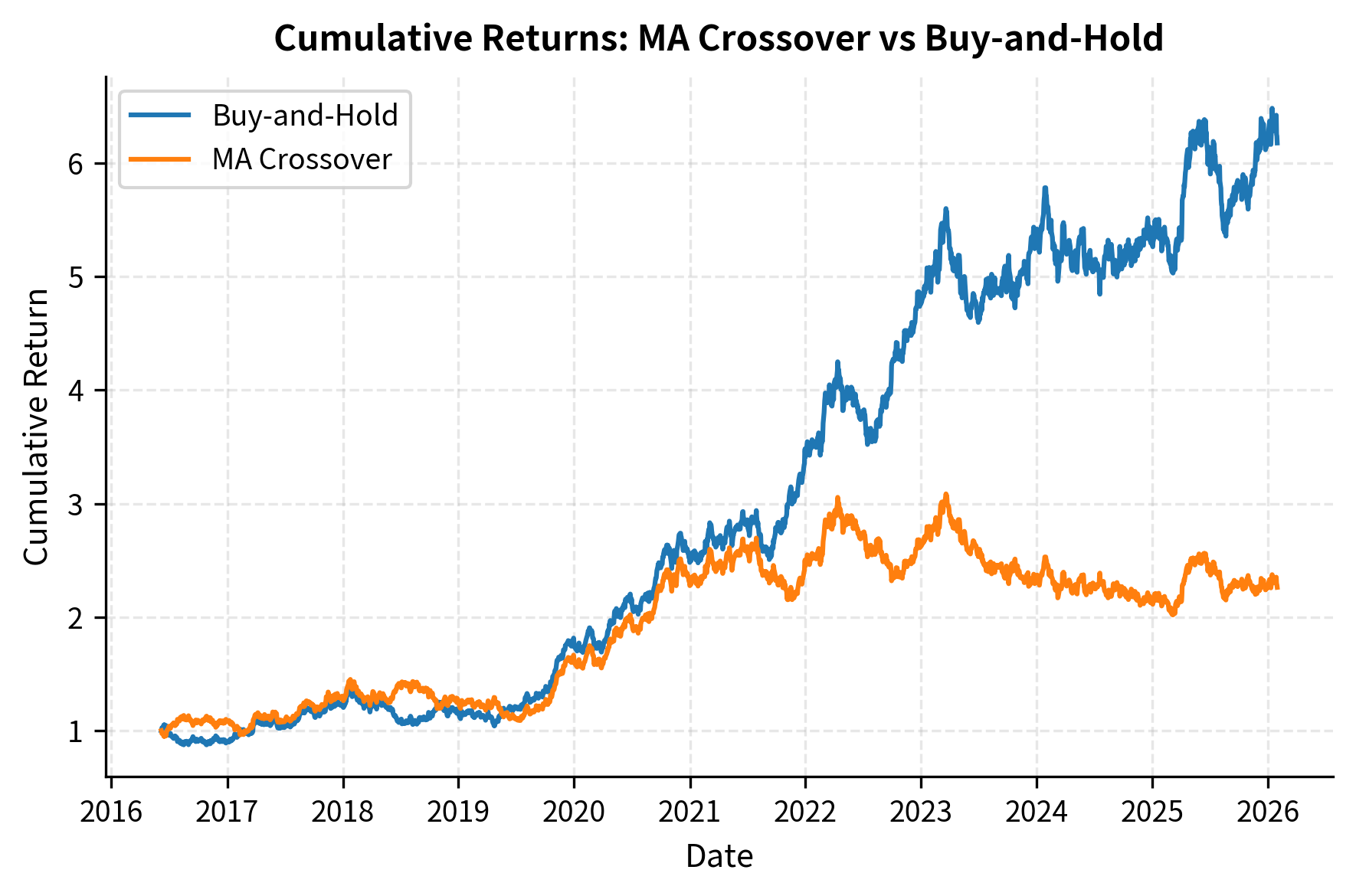

Now let's calculate the strategy's returns and compare them to buy-and-hold:

The metrics comparison highlights the trade-offs of the strategy. While the Buy-and-Hold approach tracks the market's total return, the Moving Average Crossover strategy aims to improve the Sharpe Ratio by sidestepping major drawdowns, albeit often at the cost of lower total returns during strong bull markets.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for the Moving Average Crossover strategy are:

- Fast Window: The lookback period for the short-term moving average (e.g., 50 days). Shorter windows make the strategy more responsive but prone to false signals.

- Slow Window: The lookback period for the long-term baseline (e.g., 200 days). Longer windows filter more noise but increase lag.

- Regime: The market state (trending vs. mean-reverting) heavily influences performance. Crossovers perform best in sustained trends.

Breakout Strategies

Breakout strategies represent another powerful implementation of time-series momentum, grounded in a different but related intuition. Rather than using moving average crossovers, breakout systems enter positions when prices exceed recent highs or lows. The underlying premise is that price extremes carry informational content: when an asset reaches a new high, it signals that buyers have overwhelmed sellers at all previously established price levels, suggesting strong demand that may persist. Conversely, a new low indicates that selling pressure has broken through all previous support levels.

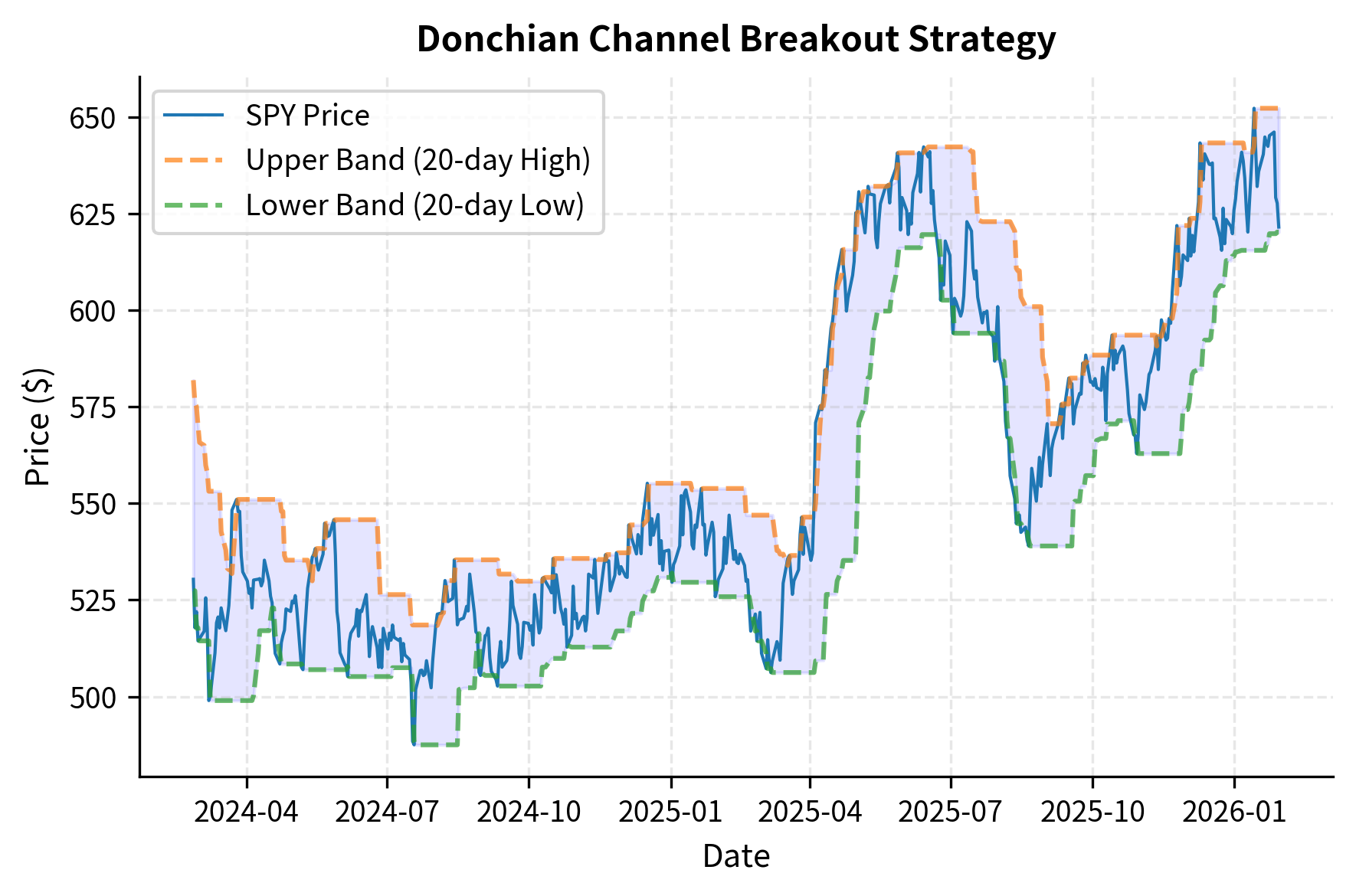

The classic Donchian channel strategy, popularized by the famous "Turtle Traders" in the 1980s, operationalizes this intuition by buying when price breaks above the highest high of the past days and selling when price breaks below the lowest low. The Turtle Traders demonstrated that this systematic approach, when combined with proper position sizing and risk management, could generate substantial profits across diverse futures markets.

The Donchian channel defines dynamic support and resistance levels based on recent price extremes:

where:

- : highest price over the past periods

- : lowest price over the past periods

- : asset price periods ago

- : lookback window size

These formulas create a price channel that contains all price action over the lookback window. The upper band represents the resistance level that buyers have been unable to breach, while the lower band represents the support level that sellers have been unable to break. When price finally moves outside this channel, it suggests a potential shift in the market's supply and demand equilibrium.

A long entry occurs when , indicating that today's price has exceeded all prices in the lookback window. This breakout above resistance suggests that new buyers have entered the market or that existing buyers have become more aggressive, potentially initiating an upward trend. A short entry occurs when , indicating that today's price has fallen below all recent support levels. This breakout logic assumes that prices reaching new extremes signal a fundamental shift in market dynamics that is likely to persist as other market participants recognize and react to the new price regime.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for Breakout strategies are:

- Lookback Period (): The window for determining the breakout levels (e.g., 20 days).

- Upper/Lower Bands: The highest high and lowest low over the lookback period, which serve as dynamic support and resistance levels.

CTA Strategies and Multi-Asset Trend Following

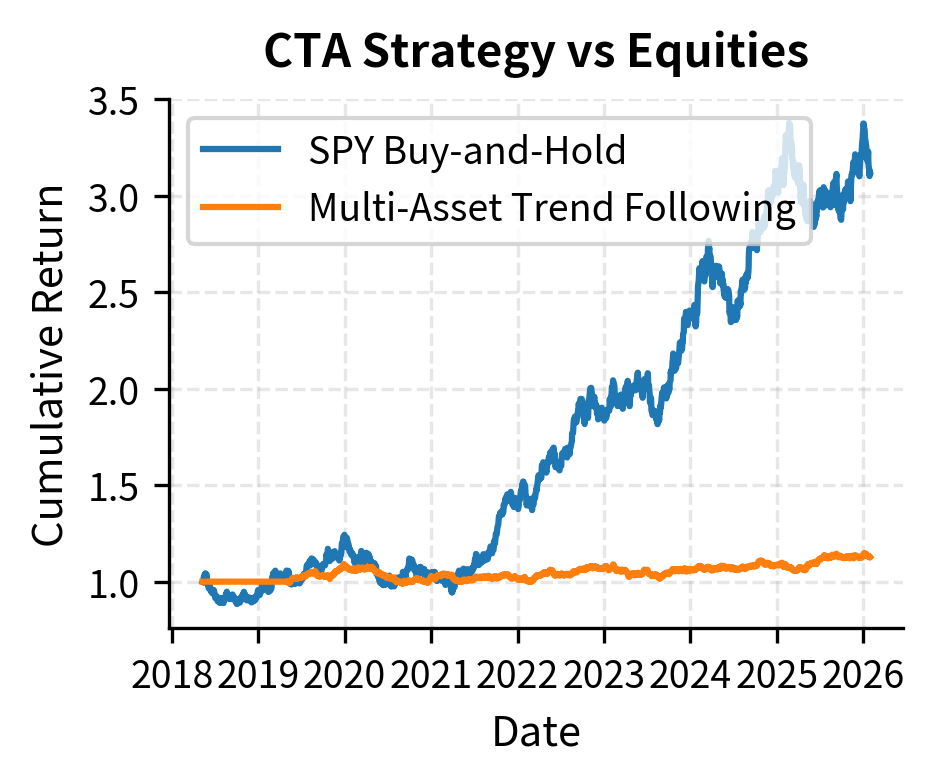

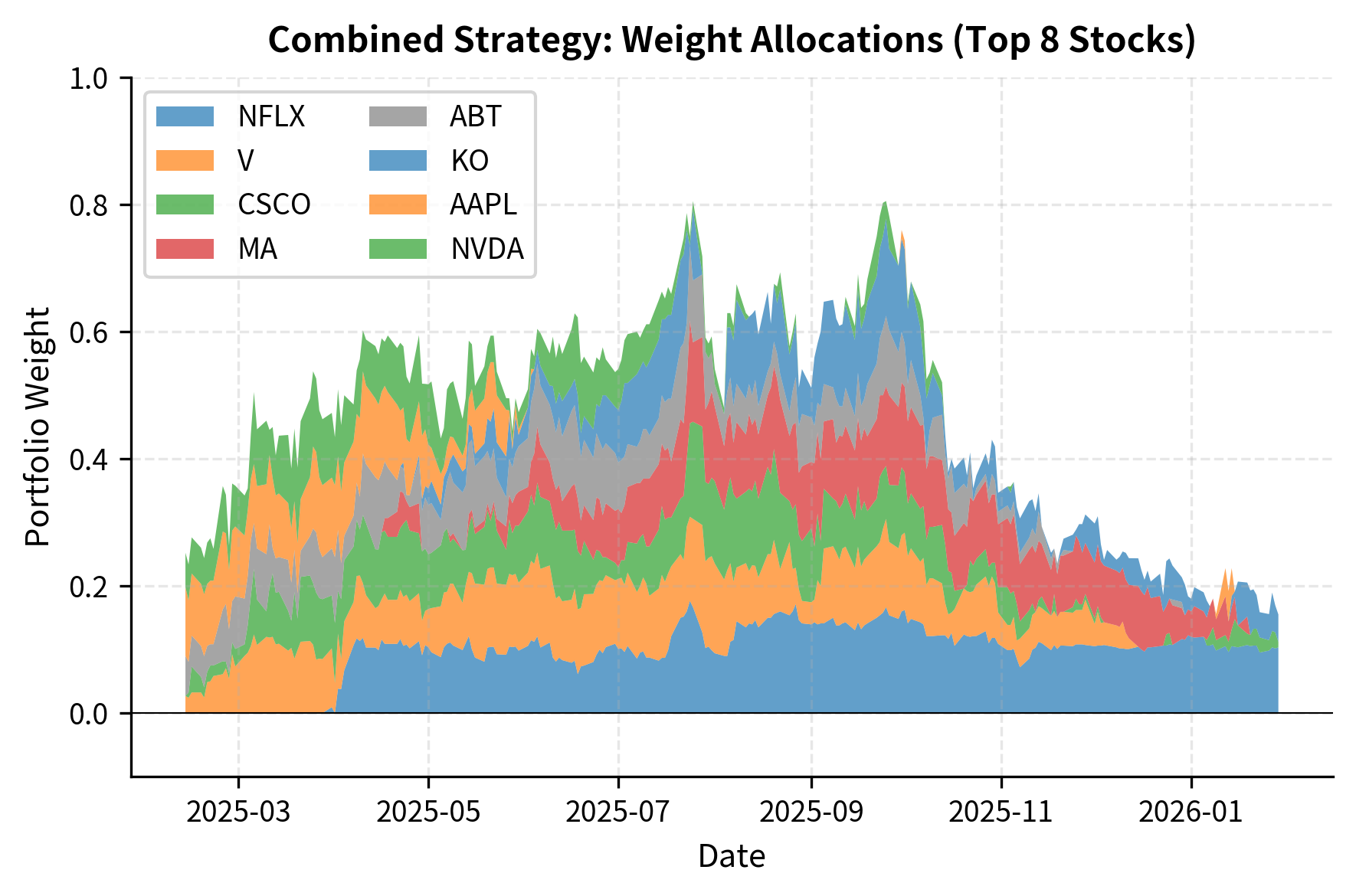

Commodity Trading Advisors (CTAs) are managed futures funds that primarily employ trend-following strategies across a diversified portfolio of futures contracts. The power of CTA strategies comes from combining trend signals across multiple uncorrelated asset classes: equity indices, government bonds, currencies, commodities, and interest rates.

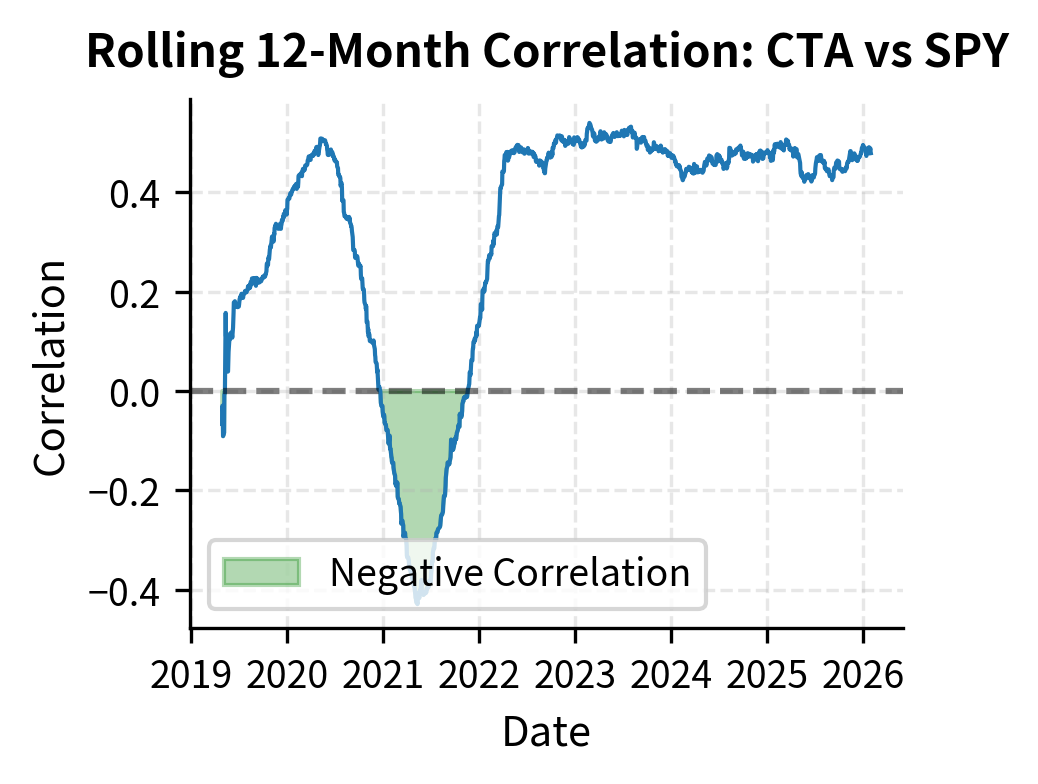

The key insight is that while any single trend signal may fail, combining signals across 50 to 100 futures markets with low correlation to each other produces a more stable return stream. The strategy also benefits from the ability to profit in both rising and falling markets, providing valuable diversification during equity bear markets.

A typical CTA strategy involves several components:

- Signal generation: Each market receives a trend signal (e.g., moving average crossover, momentum score, or breakout)

- Volatility scaling: Position sizes are inversely proportional to recent volatility, so more volatile markets receive smaller positions

- Risk allocation: Capital is allocated across asset classes and individual markets based on target risk contribution

- Portfolio construction: Final positions combine signals, volatility scaling, and risk budgets

Let's implement a simplified multi-asset trend following system:

The rolling correlation chart reveals why institutional investors value trend-following strategies: during market stress periods, the correlation often turns negative, providing protection precisely when diversification is most needed. This "crisis alpha" property stems from the strategy's ability to go short during sustained market declines.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for the Multi-Asset CTA strategy are:

- Signal Lookback: The period for measuring momentum (e.g., 12 months).

- Volatility Lookback: The window for estimating asset volatility to scale positions (e.g., 3 months).

- Target Volatility: The desired annualized volatility level for each position or the portfolio.

- Leverage Cap: Maximum leverage allowed per position to prevent excessive risk.

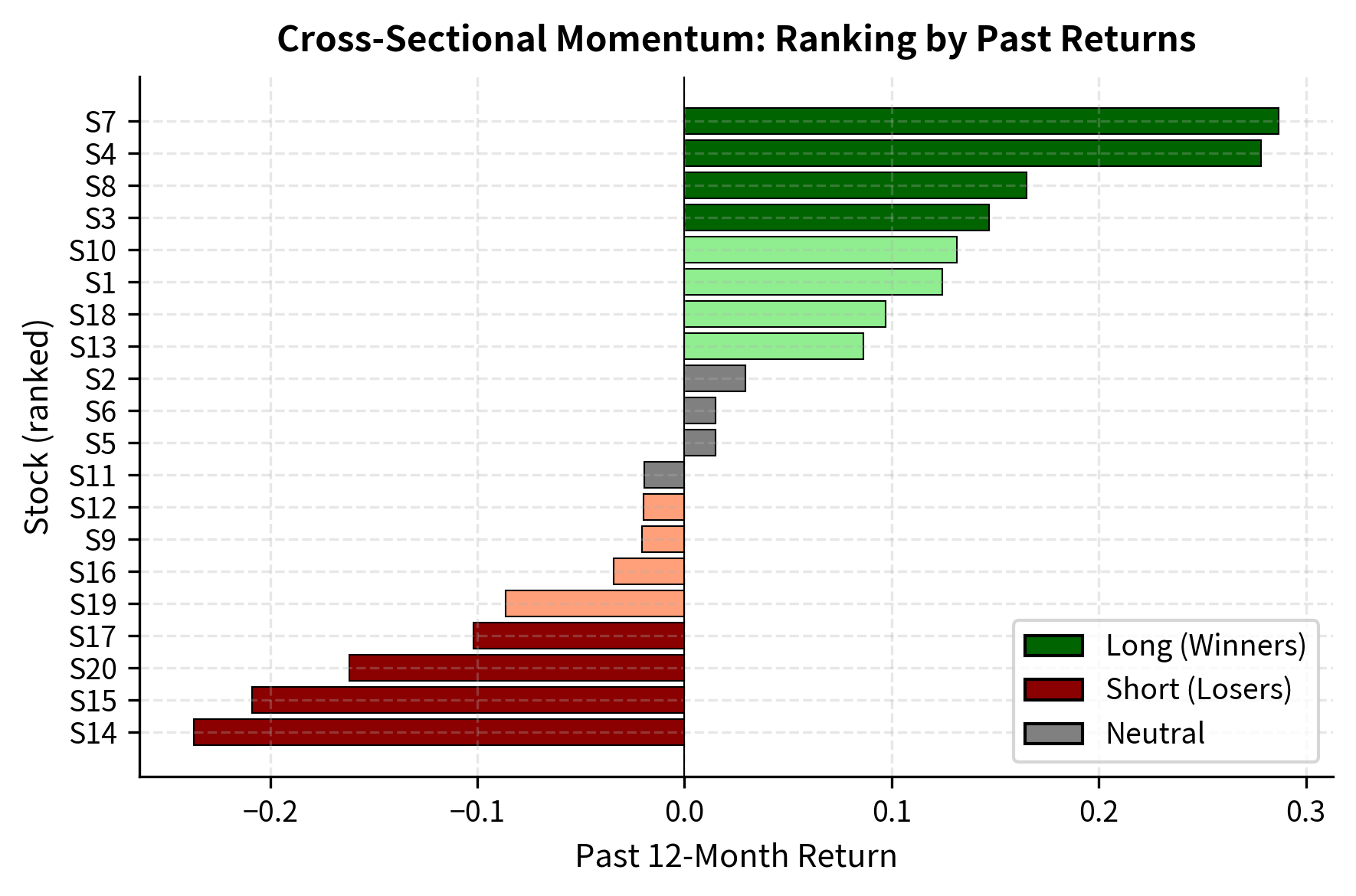

Cross-Sectional Momentum

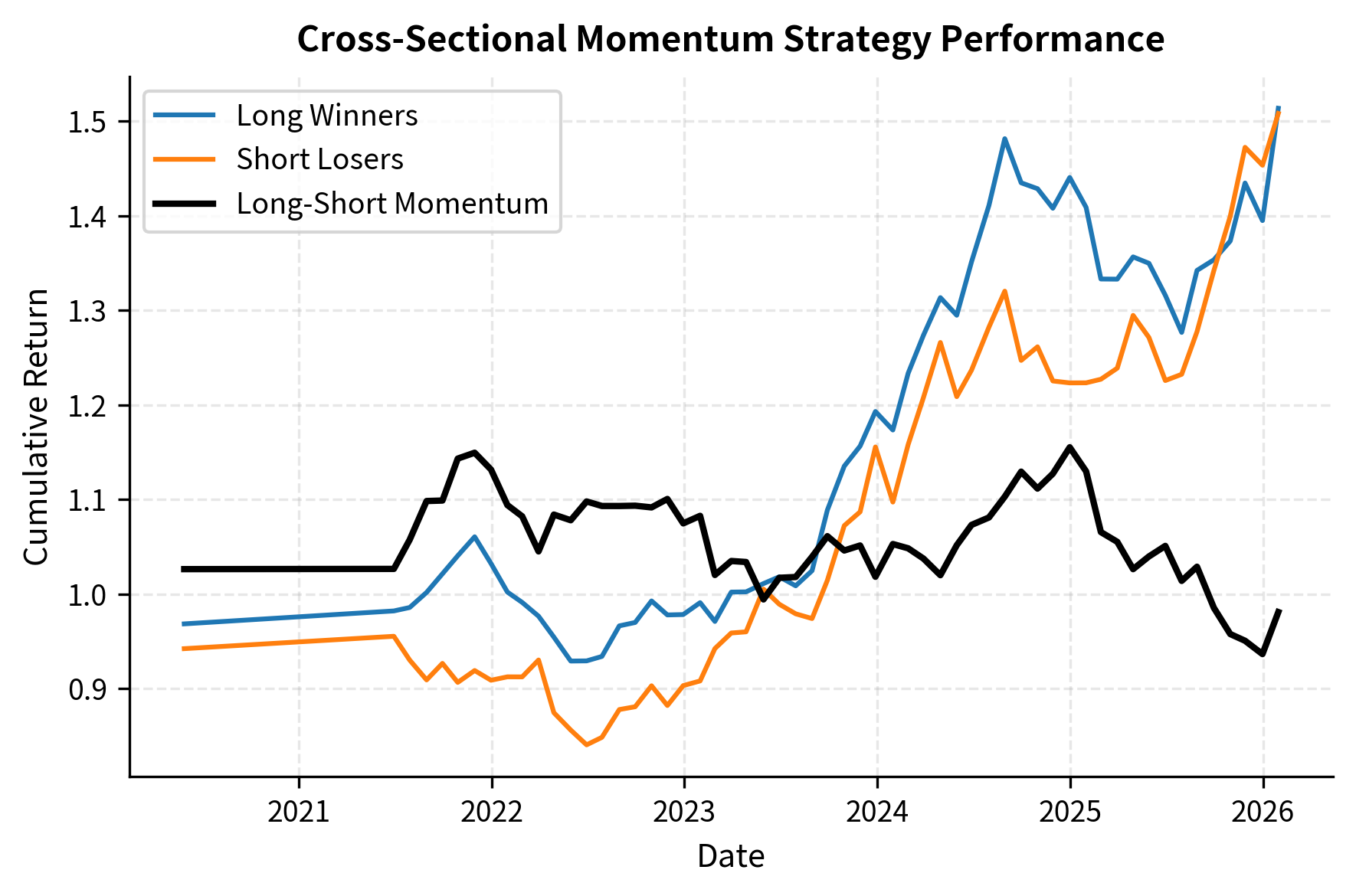

While time-series momentum compares an asset to its own history, cross-sectional momentum takes a fundamentally different approach: it ranks assets relative to their peers and takes long positions in recent winners while shorting recent losers. The distinction is subtle but important. Time-series momentum asks, "Has this asset been going up?" Cross-sectional momentum asks, "Has this asset been going up more than other similar assets?" This relative comparison exploits a different source of return persistence, one related to the dispersion in performance across assets rather than the absolute direction of any single asset.

This approach was documented in the seminal work by Jegadeesh and Titman (1993), who showed that buying stocks that performed well over the past 3 to 12 months and selling stocks that performed poorly generates significant excess returns. Their findings challenged the notion of market efficiency by demonstrating a simple, mechanical trading rule that produced consistent profits.

The Jegadeesh-Titman Framework

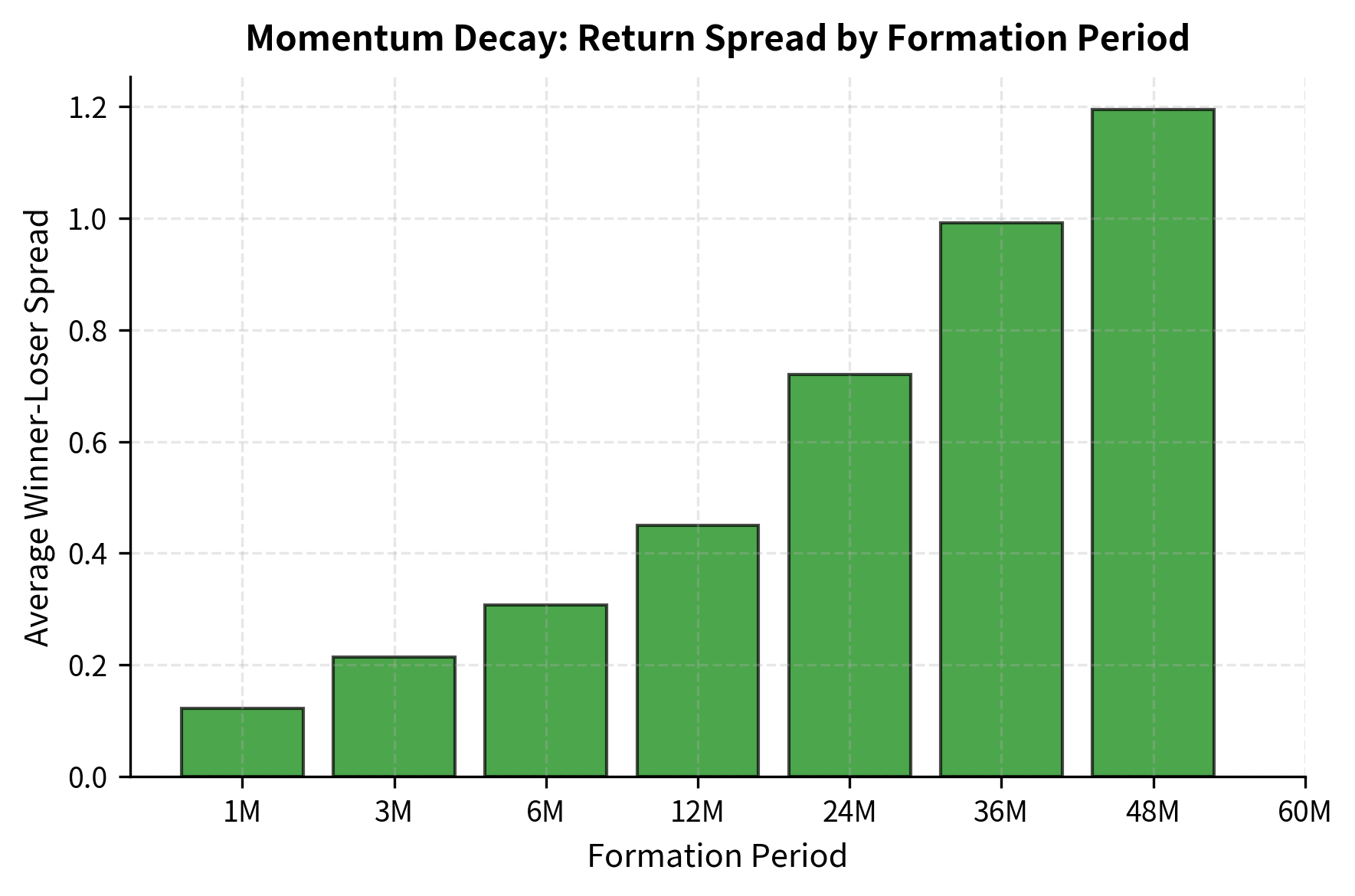

The classic cross-sectional momentum strategy involves three parameters that determine how the portfolio is constructed and managed:

- Formation period (): The lookback window for ranking stocks (typically 3, 6, or 12 months)

- Holding period (): How long positions are held (typically 3, 6, or 12 months)

- Skip period: Often 1 month is skipped between formation and holding to avoid short-term reversal effects

The formation period defines how we measure past performance, recognizing that momentum persistence varies across different time horizons. The holding period determines how long we maintain positions before rebalancing, balancing the tradeoff between capturing momentum profits and incurring transaction costs. The skip period addresses a well-documented empirical finding: stocks exhibit short-term reversal in the weeks immediately following extreme returns, so skipping a month between ranking and trading improves strategy performance.

At each rebalancing date, stocks are ranked by their formation period returns and sorted into decile portfolios. The momentum portfolio goes long the top decile (winners) and short the bottom decile (losers).

The momentum factor return captures the performance spread between recent winners and recent losers:

where:

- : return of the long-short momentum factor at time

- : return of the top decile (winner) portfolio

- : return of the bottom decile (loser) portfolio

This long-short construction creates a dollar-neutral portfolio with equal long and short exposure. The design isolates the performance spread, often interpreted as alpha, between winners and losers while hedging out the market's general direction, or beta. If the market rises 10%, both the winner and loser portfolios will likely rise, but the momentum return captures only the difference in how much each rose. This neutralization makes momentum returns relatively independent of market direction, though as we will see later, this independence breaks down during sharp market reversals.

Empirically, this spread has averaged 1% per month in US equities, though returns vary significantly over time and across markets. The magnitude and consistency of this premium attracted substantial academic attention and practical capital to momentum-based strategies.

Implementing Cross-Sectional Momentum

Let's implement a cross-sectional momentum strategy on a universe of liquid US stocks:

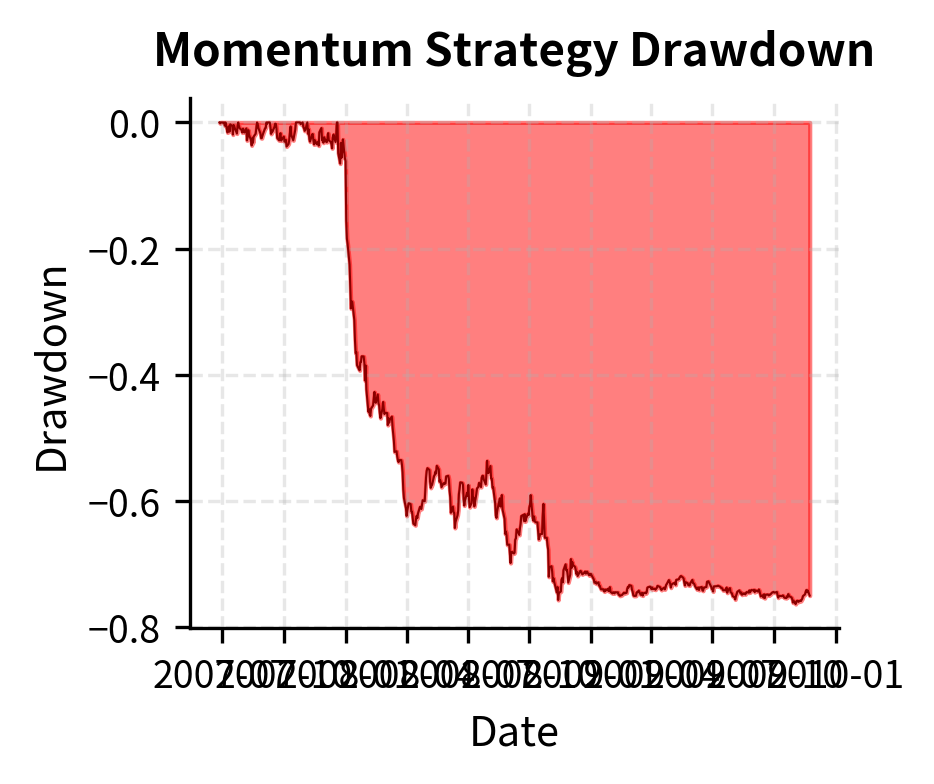

The performance metrics quantify the momentum premium captured by the strategy. A high Sharpe ratio and positive average monthly returns confirm the efficacy of buying winners and selling losers. However, the maximum drawdown indicates that the strategy is not risk-free and can suffer significant drawdowns, particularly during market reversals.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for the Cross-Sectional Momentum strategy are:

- Formation Period (): The lookback window for ranking stocks (e.g., 12 months).

- Holding Period (): The duration positions are held (e.g., 1 month).

- Skip Period: The lag between formation and holding periods (e.g., 1 month) to avoid short-term reversals.

- Portfolio Size: The number or percentage of stocks in the long and short legs (e.g., top/bottom decile).

Historical Evidence and the Momentum Premium

The momentum anomaly has been documented extensively across markets, time periods, and asset classes:

- Equity markets: Momentum profits have been found in the US (Jegadeesh and Titman, 1993), international developed markets (Rouwenhorst, 1998), and emerging markets (Rouwenhorst, 1999)

- Asset classes: Momentum works in currencies (Menkhoff et al., 2012), commodities (Miffre and Rallis, 2007), and government bonds (Moskowitz et al., 2012)

- Historical depth: Geczy and Samonov (2016) documented momentum profits in US equities back to 1801

The persistence of momentum across such diverse settings suggests it reflects fundamental aspects of how information gets incorporated into prices rather than data mining or statistical artifacts.

In factor models discussed in Part IV, momentum is captured by the UMD (Up Minus Down) factor, representing the return of recent winners minus recent losers. This factor has historically earned a premium comparable to the value and size factors, making it a crucial component of multi-factor equity strategies.

Behavioral and Structural Sources of Momentum

The profitability of momentum strategies requires explanation. If markets are efficient, past returns should not predict future returns. Several theories attempt to explain why momentum persists.

Investor Underreaction

The most widely cited explanation involves gradual information diffusion and investor underreaction. When new information arrives, prices do not immediately adjust to reflect its full implications. Instead, the adjustment occurs gradually as more investors learn about and trade on the information.

Underreaction can arise from several psychological biases:

- Conservatism bias: Investors are slow to update their beliefs when confronted with new evidence, anchoring too heavily on prior views

- Inattention: Not all investors monitor all securities continuously; information spreads gradually through the investor population

- Disposition effect: Investors are reluctant to realize losses and eager to realize gains, creating selling pressure on winners and buying pressure on losers that slows price adjustment

The underreaction hypothesis predicts that prices will continue to drift in the direction of initial news as the market gradually incorporates information, generating momentum in returns.

Overreaction and Positive Feedback

An alternative view suggests that momentum itself creates more momentum through positive feedback mechanisms:

- Herding: Investors observe others buying and interpret this as a signal of private information, leading them to buy as well

- Overconfidence: Traders who profit from momentum trades may become overconfident and increase their positions, pushing prices further

- Feedback trading: Technical traders and trend followers explicitly buy rising assets and sell falling assets, amplifying price movements

Under this view, momentum returns eventually reverse as prices overshoot fundamental value. This is consistent with long-horizon return reversals documented at 3- to 5-year horizons.

Risk-Based Explanations

A third perspective argues that momentum returns represent compensation for bearing systematic risk. Possible risk sources include:

- Crash risk: Momentum strategies are exposed to sudden, severe losses when trends reverse abruptly

- Liquidity risk: Momentum portfolios may load on less liquid securities that require compensation

- Macroeconomic risk: Winners and losers may have different exposures to business cycle risk

The debate between behavioral and risk-based explanations remains unresolved, and the truth likely involves elements of both.

Visualizing Momentum Decay

We can examine how momentum profits vary with the formation period lookback, revealing the typical pattern of return persistence and eventual reversal:

This pattern of intermediate-horizon momentum followed by long-horizon reversal is consistent with both the initial underreaction and subsequent overreaction hypotheses.

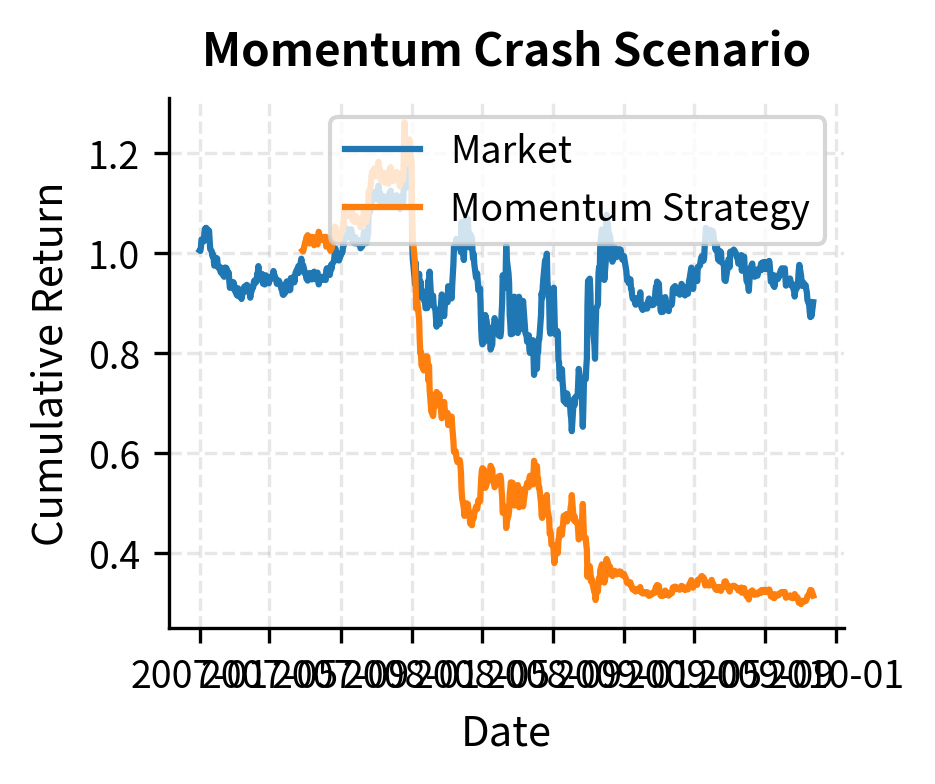

Momentum Risks and Crashes

Despite its historical profitability, momentum is subject to significant risks that can produce catastrophic losses. Understanding these risks is essential for you.

Momentum Crashes

The most severe risk facing momentum strategies is the momentum crash: sudden, violent reversals that produce large losses in a short time. The most famous example occurred in March-May 2009, when momentum strategies lost over 40% in just two months as previously battered financial stocks surged and prior winners collapsed.

Momentum crashes share common characteristics:

- They typically occur after extended market declines when losers are at extreme valuations

- They coincide with sharp market reversals (bear market rallies)

- They involve a rapid unwind as trend followers simultaneously reverse positions

- Losses can exceed years of accumulated profits in weeks

The simulation demonstrates the asymmetry of momentum crashes: gains accumulate gradually over the "normal" period, but the reversal during the recovery phase (when losers outperform winners) wipes out substantial value in a fraction of the time.

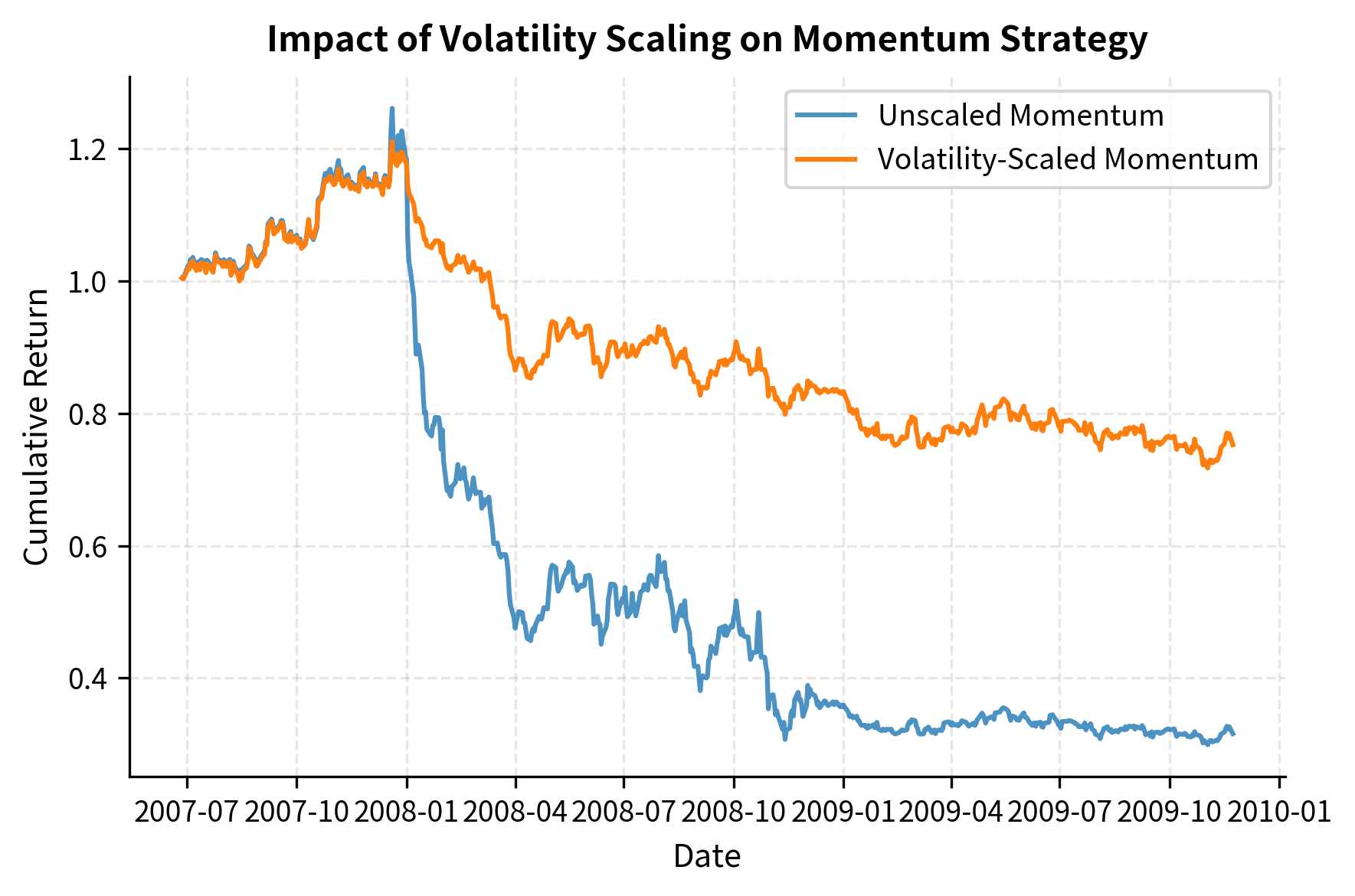

Mitigating Momentum Crash Risk

Several techniques can reduce, though not eliminate, momentum crash risk:

- Volatility scaling: Reduce position sizes when market volatility rises, as crashes often occur in high-volatility regimes

- Dynamic hedging: Combine momentum with value or mean reversion to offset crash exposure

- Option protection: Purchase put options on momentum portfolios as tail risk insurance

- Faster signal adaptation: Use shorter lookback periods that can reverse more quickly

- Diversification: Spread momentum across uncorrelated asset classes and markets

The comparison shows that volatility scaling helps stabilize performance. By reducing exposure when market risk is high, the scaled strategy often suffers a smaller maximum drawdown compared to the unscaled version. Volatility scaling typically improves risk-adjusted returns by reducing exposure during high-volatility crash periods while maintaining exposure during calmer trending periods.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for Volatility Scaling are:

- Volatility Lookback: Window used to estimate recent market volatility (e.g., 21 days).

- Target Volatility: The annualized volatility level the strategy aims to maintain.

- Scaling Factor: The multiplier applied to positions, inversely proportional to realized volatility.

Crowding and Capacity Constraints

As momentum strategies have become more widely adopted, crowding has become a significant concern. When many investors pursue similar momentum trades:

- Entry and exit points become more predictable, inviting front-running

- Position building takes longer as everyone tries to buy the same stocks

- Liquidation events become more severe as positions are unwound simultaneously

- Alpha decays as the strategy becomes arbitraged away

You respond to crowding by differentiating your signals (using proprietary data or alternative construction methods), trading more patiently, and monitoring crowding indicators such as short interest concentration or factor positioning surveys.

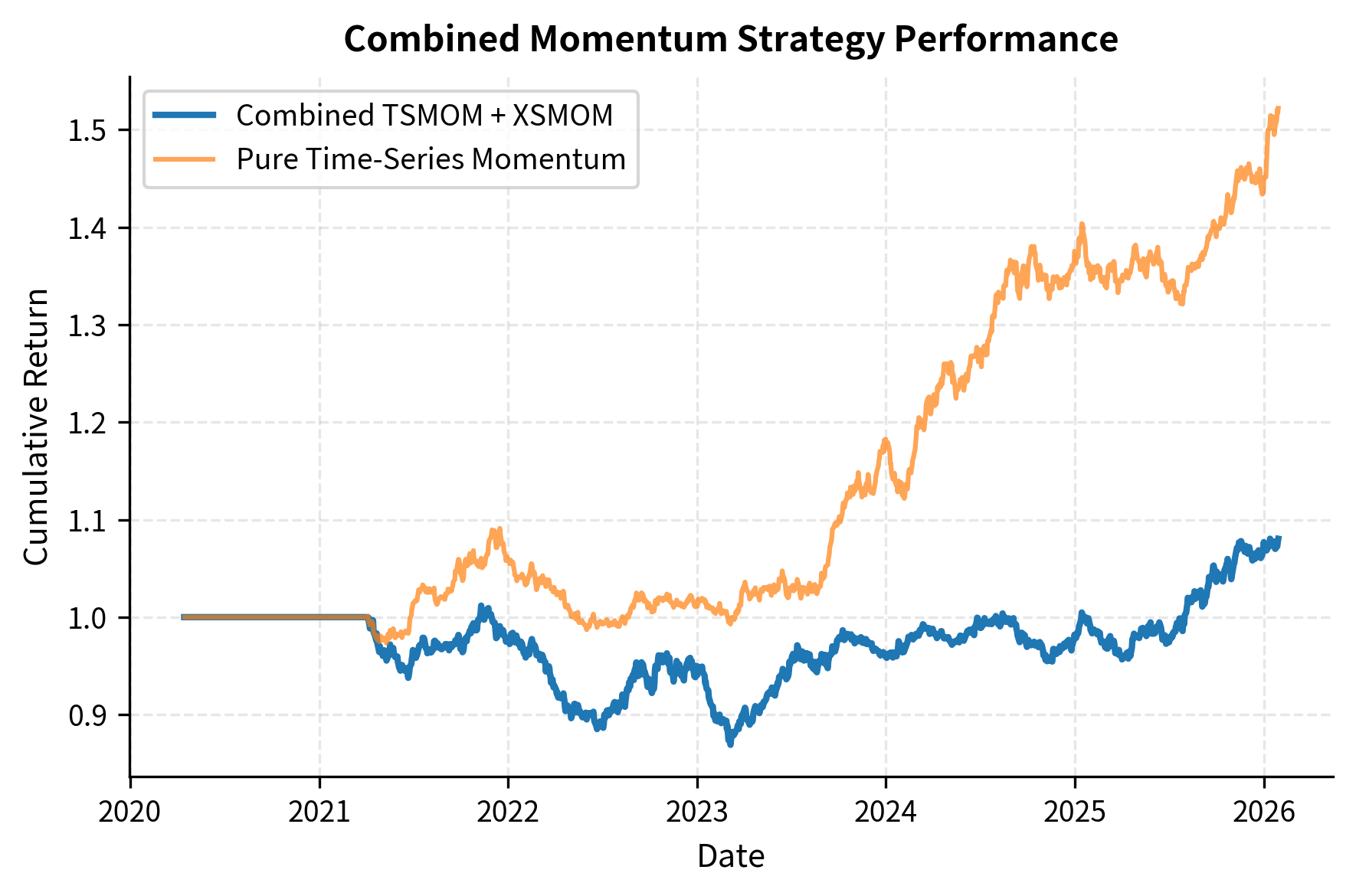

Combining Time-Series and Cross-Sectional Momentum

Sophisticated momentum strategies often combine both time-series and cross-sectional signals. Time-series momentum provides absolute direction (should we be long or short the asset class?), while cross-sectional momentum provides relative selection (which assets within the class should we overweight?).

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Momentum strategies, while historically profitable, face several practical challenges that affect real-world implementation.

Transaction costs represent a significant drag on momentum returns. High-turnover strategies that frequently rebalance between winners and losers incur substantial trading costs, particularly when dealing with less liquid securities. Studies that account for realistic transaction costs often find that momentum profits are substantially reduced, especially for strategies using shorter formation and holding periods. You must carefully balance signal freshness against turnover, often implementing partial rebalancing or threshold-based trading rules to reduce costs.

The risk of regime change poses an existential threat to momentum strategies. The anomaly has been documented extensively since the 1990s, attracting substantial capital to momentum-based strategies. As more assets chase the same patterns, the equilibrium expected return should decline. Some researchers argue that momentum profits have already diminished in recent decades, while others contend that the behavioral roots of momentum ensure its persistence. Regardless, you should expect future returns to be lower than historical backtests suggest and should continuously monitor for signs of strategy decay.

Short-selling constraints create asymmetry between the long and short legs of cross-sectional momentum. Shorting stocks involves borrowing costs, potential recalls, and regulatory restrictions that do not affect long positions. Additionally, the short leg often consists of distressed or high-volatility stocks that are difficult and expensive to borrow. Many implementations of momentum focus primarily on the long leg or use long-only momentum-tilted portfolios rather than attempting dollar-neutral long-short strategies.

Finally, momentum strategies interact with other factors in ways that can reduce or enhance returns. Momentum tends to be negatively correlated with value strategies at short horizons, as recent winners often appear expensive while recent losers appear cheap. This creates natural hedging opportunities when combining momentum with value in multi-factor portfolios. We will explore these factor interactions further in the next chapter on Factor Investing and Long/Short Equity.

Summary

Trend following and momentum strategies exploit the tendency of asset prices to exhibit persistence, buying recent winners and selling recent losers. This chapter covered the two main variants of momentum investing and their practical implementation:

Time-series momentum compares an asset's current price to its own history, generating long or short signals based on the direction of recent returns. Moving average crossovers and breakout systems are common implementations. CTA strategies apply time-series momentum across diversified portfolios of futures contracts, benefiting from low correlation to traditional assets and the ability to profit in both rising and falling markets.

Cross-sectional momentum ranks assets relative to their peers, going long the top performers and short the bottom performers. The Jegadeesh-Titman framework established that buying 6- to 12-month winners and selling losers generates significant excess returns across equity markets, time periods, and asset classes.

Behavioral explanations for momentum include investor underreaction to new information, herding behavior, and positive feedback trading. Risk-based explanations suggest momentum returns compensate for crash risk and other systematic exposures. The truth likely involves elements of both.

Momentum crashes represent the strategy's most severe risk, with sudden reversals capable of erasing years of profits in weeks. Volatility scaling, diversification, and dynamic hedging can mitigate but not eliminate this risk. Strategy crowding presents an additional concern as momentum becomes more widely adopted.

The combination of time-series and cross-sectional momentum often produces more robust results than either approach alone. In the next chapter, we will see how momentum combines with other factors such as value, quality, and low volatility in systematic long-short equity strategies.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about trend following and momentum strategies.

Comments