Explore market microstructure mechanics including order book architecture, matching algorithms, and order types. Master liquidity analysis and execution logic.

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Market Microstructure and Order Types

When you submit an order to buy 1,000 shares of Apple, what actually happens? The answer is far more complex than "someone sells it to you." Your order enters an intricate ecosystem of competing exchanges, order books, matching engines, and execution protocols that determine not just whether your trade executes, but at what price, in what sequence, and with what impact on subsequent prices.

Market microstructure is the study of how trades are executed and prices are formed at the granular level. While traditional finance often treats markets as frictionless, assuming you can buy or sell any quantity at the current price, reality is messier. Orders queue in electronic order books, compete for execution priority, and leave footprints that move prices. Understanding these mechanics is essential for you to translate theoretical strategies into actual executed positions.

Building on our discussion of transaction costs and market impact in the previous chapter, we now examine the underlying plumbing: the order book architecture that determines execution, the taxonomy of order types available to traders, and the rules that govern how orders interact. This knowledge directly informs the execution algorithms we'll develop in the next chapter on optimal execution.

The Order Book

The order book is the central mechanism through which modern electronic markets operate. It's a real-time record of all outstanding buy and sell orders for a security, organized by price level and arrival time.

Structure of the Order Book

Before diving into the technical definition, it helps to understand what problem the order book solves. In any market, buyers and sellers rarely arrive at exactly the same moment with perfectly matching quantities and prices. Someone who wants to sell 500 shares right now may not find a buyer willing to take exactly 500 shares at that exact instant. The order book solves this coordination problem by serving as a persistent record of trading interest, allowing buyers and sellers to express their willingness to trade at specific prices and wait for counterparties to arrive.

An order book is a list of all outstanding limit orders to buy (bids) and sell (asks/offers) a security organized by price level. It represents the current supply and demand for immediate execution at each price point.

The order book has two sides: the bid side contains all buy orders, and the ask side (or offer side) contains all sell orders. Orders on each side are sorted by price, with the most aggressive prices at the top. The highest bid is called the best bid, and the lowest ask is called the best ask (or best offer). The difference between these two prices is the bid-ask spread.

To quantify the key features of the order book, we define two fundamental measures that traders constantly monitor. The spread captures the cost of trading immediately, while the midprice provides a reference point for the security's theoretical fair value. These quantities are defined mathematically as follows:

Let us examine each component of these formulas to understand their economic meaning:

- : best ask price (lowest price to buy). This represents the minimum price at which someone in the market is currently willing to sell. If you want to buy immediately, this is the price you will pay.

- : best bid price (highest price to sell). This represents the maximum price at which someone is currently willing to buy. If you want to sell immediately, this is the price you will receive.

- : bid-ask spread, representing the cost of immediacy. The spread is always non-negative in a properly functioning market, since the best ask must be at least as high as the best bid (otherwise orders would immediately cross and execute). A narrow spread indicates a liquid market where trading is cheap, while a wide spread suggests illiquidity or uncertainty.

- : midprice, representing the theoretical fair value. The midprice sits exactly halfway between the best bid and ask, and we often use it as a reference point for the "true" price of the security. However, the midprice is not a price at which you can actually trade; it is merely a convenient benchmark.

Let's create a simple order book class that captures the essential mechanics:

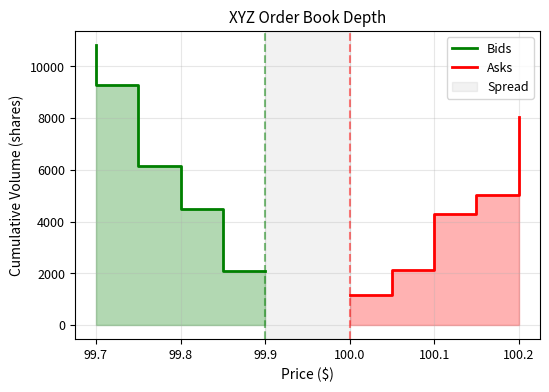

Now let's populate an order book with some sample orders and visualize it:

The order book reveals several key pieces of information. The spread of $0.10 represents the cost of immediacy: if you want to buy immediately, you pay the ask ($100.00), but if you're willing to wait, you could place a bid at $99.90. The depth at each level shows how much liquidity is available before the price moves to the next level.

Visualizing Order Book Depth

A depth chart provides an intuitive visualization of the order book, showing cumulative volume at each price level:

The depth chart shows how much buying power exists at each price level below the current price (bids) and how much selling pressure exists above (asks). The steeper the curve, the more liquidity is concentrated near the best prices. Shallow curves indicate thin markets where even modest order sizes can move prices significantly.

Order Types

Understanding order types is crucial for implementing trading strategies effectively. Each order type serves a specific purpose and carries different execution characteristics and risks.

Market Orders

The most fundamental question a trader faces is whether to trade now or wait. Market orders represent the choice to trade immediately, accepting whatever price the market offers in exchange for certain execution. This trade-off between price and certainty lies at the heart of all order type decisions.

A market order is an instruction to buy or sell immediately at the best available price. Market orders guarantee execution (in liquid markets) but not the execution price.

Market orders are the simplest order type: you want to trade now, regardless of price. When you submit a market buy order, it executes against the best available ask prices in the order book, consuming liquidity until your order is filled. The execution process follows the order book's price levels sequentially: your order first takes all available shares at the best ask, then moves to the next price level if more shares are needed, and continues until completely filled.

The key characteristics of market orders include:

- Immediate execution: Your order fills right away against standing limit orders

- Price uncertainty: The execution price depends on available liquidity

- Liquidity consumption: You remove liquidity from the order book, typically paying a fee

- Slippage risk: Large orders may walk through multiple price levels

The slippage risk deserves particular attention. When your order size exceeds the available quantity at the best price, you experience slippage: the average execution price differs from the initial best price. This is not a market malfunction; it is the natural consequence of consuming multiple price levels to complete a large order.

Let's implement market order execution in our order book:

Let's see how a market order executes and potentially walks through multiple price levels:

The market order walked through three price levels to fill completely. Starting at the best ask of $100.00, it consumed 800 shares, then moved to $100.05 for another 400 shares, and finally took 300 shares at $100.10. This price impact is exactly what we analyzed in the previous chapter on transaction costs.

Limit Orders

If market orders represent the choice to trade immediately, limit orders represent the opposite choice: patience in exchange for price control. A limit order says "I am willing to trade, but only at a price I consider acceptable." This patience comes with a cost, since there is no guarantee the market will ever reach your price.

A limit order is an instruction to buy at or below a specified price (limit buy) or sell at or above a specified price (limit sell). Limit orders guarantee the execution price but not execution itself.

Limit orders provide price protection at the cost of execution certainty. A limit buy order at $99.90 will only execute at $99.90 or better (lower). If the market never trades at that price, your order never fills. This creates a fundamental asymmetry between what you request and what you receive: you know with certainty the worst price you can get, but you cannot know whether you will get any price at all.

Key characteristics of limit orders include:

- Price certainty: You know the worst price you'll receive

- Execution uncertainty: Your order may never fill if the price doesn't reach your limit

- Liquidity provision: You add liquidity to the order book, often receiving a rebate

- Queue position: Your place in line at a price level affects fill probability

The concept of queue position is particularly important and often overlooked if you are new to trading. When you place a limit order at a price level where other orders already exist, you join a queue. Your order will not execute until all orders ahead of you at that price have been filled. This means that simply having an order at the "right" price is not enough; you must also arrive early enough to be near the front of the queue.

Stop Orders

While market and limit orders express immediate trading intentions, stop orders represent contingent instructions: "If the market moves to a certain level, then I want to trade." This conditional nature makes stop orders essential tools for risk management, allowing traders to automate their response to adverse price movements.

A stop order (or stop-loss order) becomes active only when the market price reaches a specified trigger price. Once triggered, it converts to either a market order (stop-market) or a limit order (stop-limit).

Stop orders are used primarily for risk management: to limit losses or protect profits. A stop-loss sell order at $95 for a stock you bought at $100 will trigger if the price drops to $95 potentially limiting your loss. The order remains dormant until the trigger condition is met, at which point it activates and enters the normal order flow.

The mechanics work as follows:

- Stop-market order: Trigger price reached → converts to market order → immediate execution at available prices

- Stop-limit order: Trigger price reached → converts to limit order → executes only at limit price or better

The danger with stop-market orders is that in fast-moving markets, the execution price can be significantly worse than the stop price. Consider a gap opening: if a stock closes at $97 and opens the next day at $92 due to overnight news, a stop-market order with a $95 trigger will execute at approximately $92 far below the intended protection level. Stop-limit orders provide price protection but may not execute if the market gaps through your limit, leaving you with no protection at all.

Stop-Limit Example

Consider a trader holding shares purchased at $100 who wants downside protection:

Order Priority and Matching

When multiple orders exist at the same price level, the exchange must determine which orders execute first. The rules governing this priority are fundamental to understanding execution dynamics.

Price-Time Priority

The most common priority scheme is price-time priority (also (also called FIFO, first-in-first-out), used by exchanges like NYSE and NASDAQ, This system establishes a fair and predictable framework for determining execution order, rewarding both aggressive pricing and early arrival.

The priority rules work in a hierarchical manner:

-

Price priority: Orders at better prices always execute first. A bid at $100.01 executes before a bid at $100.00. This makes economic sense: if you are willing to pay more (or accept less), your order should receive preferential treatment.

-

Time priority: Among orders at the same price, earlier orders execute first. If you submit a bid at $100.00 at 9:30:00 and another trader submits at $100.00 at 9:30:01, your order has priority. This rewards market participants who commit to their prices early rather than waiting to see how the market evolves.

This creates a "queue" at each price level, and your position in the queue significantly affects fill probability:

Being near the front of the queue dramatically improves fill probability. This is why high-frequency traders invest heavily in latency: arriving microseconds earlier can mean the difference between the front and the back of the queue.

Pro-Rata Matching

Some markets, particularly options exchanges and certain futures markets, use pro-rata matching instead of pure time priority. This alternative system creates different incentive structures for market participants. Under pro-rata:

- Price priority still applies: best-priced orders execute first

- Size priority: At the same price, orders are filled proportionally to their size

If 1,000 shares trade at $100.00 and there are three orders at that price (500, 300, and 200 shares), each gets a proportional fill: 500, 300, and 200 respectively if the incoming order is large enough, or proportionally smaller amounts.

Pro-rata matching encourages larger order sizes since bigger orders get proportionally larger fills, regardless of arrival time. This creates different strategic considerations compared to price-time priority.

Order Lifecycle

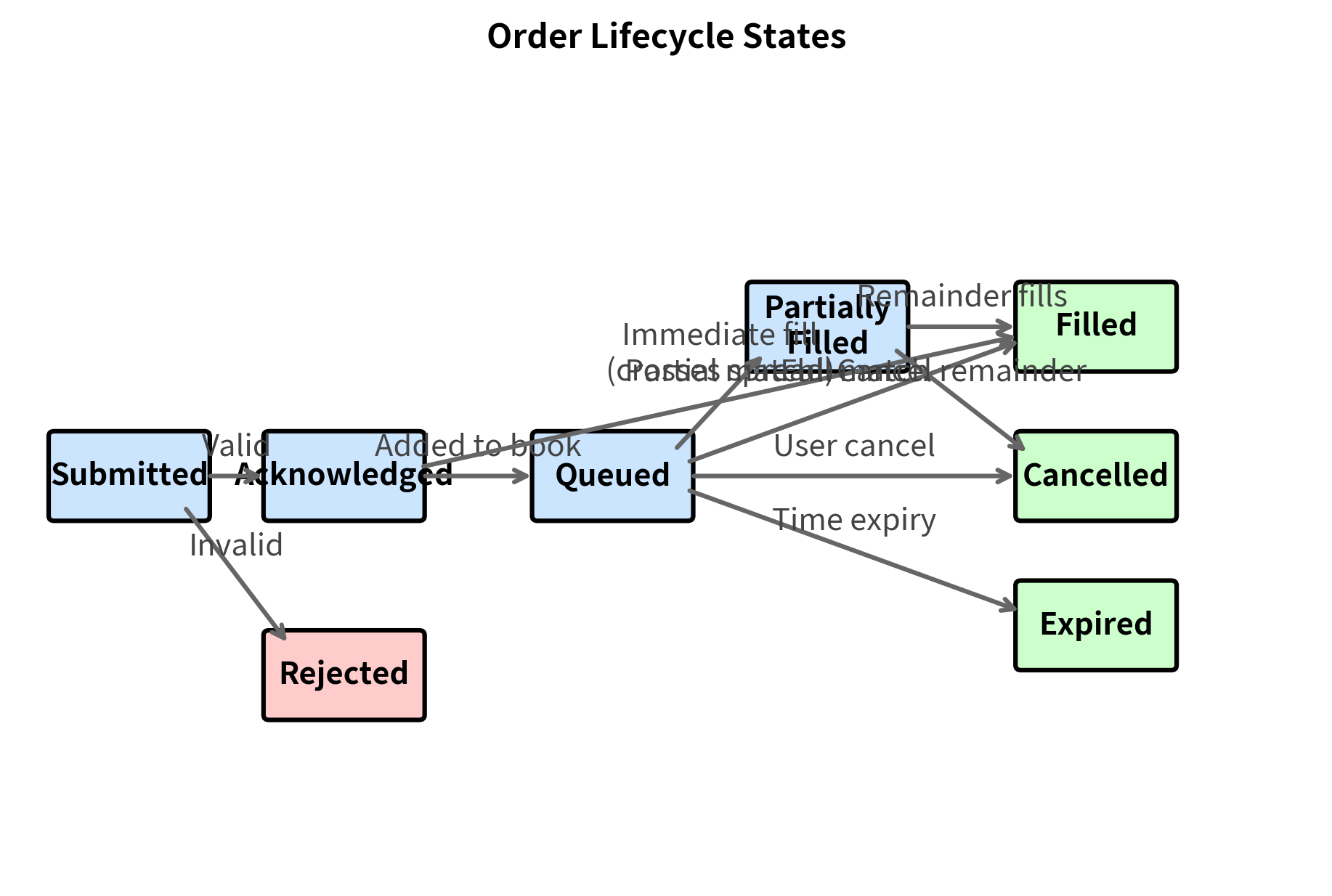

An order goes through several states from submission to final disposition. Understanding this lifecycle is essential for building robust trading systems that can handle every possible outcome. The journey begins when the order is submitted to the exchange or broker and ends in one of several terminal states.

When an order is first submitted, it enters an acknowledgment phase where the exchange validates its parameters. If the order passes validation, it may either execute immediately (if it crosses the spread) or join the queue at its specified price level. From the queued state, the order can follow multiple paths: it may receive partial fills as counterparties arrive, eventually completing when fully filled. Alternatively, it may be cancelled by you, or it may expire if it carries a time-in-force restriction that is reached. If the initial validation fails, perhaps due to an invalid price or insufficient margin, the order is rejected and never enters the book.

Understanding the order lifecycle is essential for building robust trading systems. Your system must handle each state transition, including partial fills that may occur over extended periods and unexpected rejections due to risk checks or connectivity issues.

Advanced Order Types

Beyond basic market and limit orders, exchanges and brokers offer specialized order types designed for specific trading needs.

Immediate-or-Cancel (IOC)

An IOC order executes whatever quantity is immediately available and cancels the remainder. If you submit an IOC buy for 1,000 shares and only 400 are available at your limit price, you receive 400 shares and the remaining 600-share request is cancelled.

IOC orders are useful when you want to take available liquidity without leaving a footprint in the order book.

Fill-or-Kill (FOK)

A FOK order must execute in its entirety immediately, or it is cancelled completely. Unlike IOC, there are no partial fills. This is used when partial execution would be undesirable, such as when hedging an exact position size.

Good-Till-Cancelled (GTC)

Most orders are day orders; they expire at market close if unfilled. A GTC order remains active until it executes or is explicitly cancelled, potentially staying on the books for weeks or months.

Iceberg Orders (Reserve Orders)

You might face a dilemma when executing large orders: you need to execute substantial orders, but displaying your full size would reveal your intentions and move prices against you. Iceberg orders solve this problem by splitting the order into a visible portion and a hidden reserve.

An iceberg order displays only a portion of the total order quantity in the visible order book. As the visible portion executes, more quantity is automatically revealed from the hidden reserve.

Iceberg orders help you minimize market impact by hiding the true size of your interest:

We look for 'iceberg detection' patterns repeated fills at the same price level that keep replenishing suggest hidden liquidity.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for Iceberg Orders are:

- Total Quantity: The full size of the order to be executed. This represents your complete trading interest.

- Display Quantity: The portion of the order visible in the order book at any given time. This should be set large enough to attract counterparties but small enough to avoid revealing the true order size.

- Hidden Quantity: The remaining quantity kept off the book, calculated as the difference between total quantity and display quantity. This hidden portion automatically replenishes the visible portion as fills occur.

- Price: The limit price at which the order is placed. The entire order, both visible and hidden portions, executes only at this price or better.

Pegged Orders

Pegged orders automatically adjust their price relative to a reference point such as the NBBO (National Best Bid/Offer), midpoint, or a benchmark.

The main types of pegged orders include:

- Primary peg: Pegged to the same-side NBBO (bid for buy orders, ask for sell orders)

- Midpoint peg: Pegged to the midpoint between bid and ask

- Market peg: Pegged to the opposite-side NBBO

Midpoint-pegged orders are popular for passive execution strategies because they potentially receive price improvement (better than the visible bid or ask) while still participating when the spread moves.

Algorithmic Order Types

Many brokers offer high-level algorithmic order types that translate into sophisticated execution strategies:

- VWAP (Volume-Weighted Average Price): Execute throughout the day to match the market's volume pattern, targeting the volume-weighted average price

- TWAP (Time-Weighted Average Price): Execute evenly over a specified time period

- Percentage of Volume (POV): Execute as a target percentage of market volume

- Implementation Shortfall: Minimize the difference between decision price and execution price

As we discussed in the chapter on transaction costs, these algorithms balance the trade-off between market impact and timing risk. We'll explore their implementation in detail in the next chapter on execution algorithms.

Bid-Ask Spread and Liquidity

The bid-ask spread is perhaps the most fundamental indicator of market liquidity. It represents the cost of immediacy: the price you pay for instant execution versus patient limit orders.

Components of the Spread

Why does the spread exist at all? Why don't market makers simply quote the same price on both sides? The answer lies in the risks and costs that market makers face. They must be compensated for maintaining operations, holding inventory that may lose value, and trading against participants who possess superior information. The spread serves as this compensation.

The bid-ask spread compensates market makers for several costs and risks:

- Order processing costs: The fixed costs of maintaining market-making operations

- Inventory risk: The risk that prices move against the market maker's accumulated position

- Adverse selection: The risk of trading against informed traders who have superior information

Mathematically, we can decompose the total spread into these three components:

This decomposition provides insight into why spreads vary across different securities and market conditions. Let us examine each component:

- : total bid-ask spread, the observable difference between the best ask and best bid prices

- : order processing component (fixed costs). This includes the infrastructure costs of running a trading operation: technology, connectivity, regulatory compliance, and personnel. For highly automated market makers, this component is relatively small and stable.

- : inventory risk component, proportional to volatility and position size. When a market maker buys shares from a seller, they hold inventory that may decline in value before they can sell it. Higher volatility increases this risk, requiring wider spreads as compensation.

- : adverse selection component, reflecting the probability of trading against better-informed participants. If some traders have superior information about future prices, the market maker loses money on average when trading with them. To break even, the market maker must recover these losses from uninformed traders through wider spreads.

The results illustrate how market characteristics drive spread composition. For the Small Cap Biotech stock, adverse selection and inventory risks constitute a much larger portion of the spread compared to the Large Cap Tech stock, reflecting higher volatility and lower liquidity.

The adverse selection component is particularly important for you. When you have better information than the market, you benefit from the adverse selection cost that market makers embed in spreads. Conversely, when you're trading without an edge, you're paying this cost to informed traders.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for the spread decomposition model are:

- spread: The observed bid-ask spread in the market. This is the starting point for decomposition and represents the total cost of crossing from bid to ask.

- volatility: The volatility of the asset, which increases inventory risk. Higher volatility means greater potential for adverse price movements while the market maker holds inventory.

- volume: Trading volume, used here as a proxy for liquidity and adverse selection risk. Higher volume typically correlates with lower adverse selection since uninformed traders constitute a larger share of the flow.

- tick_size: The minimum price increment, acting as a lower bound for the spread. Regulatory requirements and exchange rules establish this minimum, which constrains how narrow spreads can become even for the most liquid securities.

Order Book Depth and Liquidity

Beyond the spread, the depth of the order book at various price levels indicates how much liquidity is available before prices move:

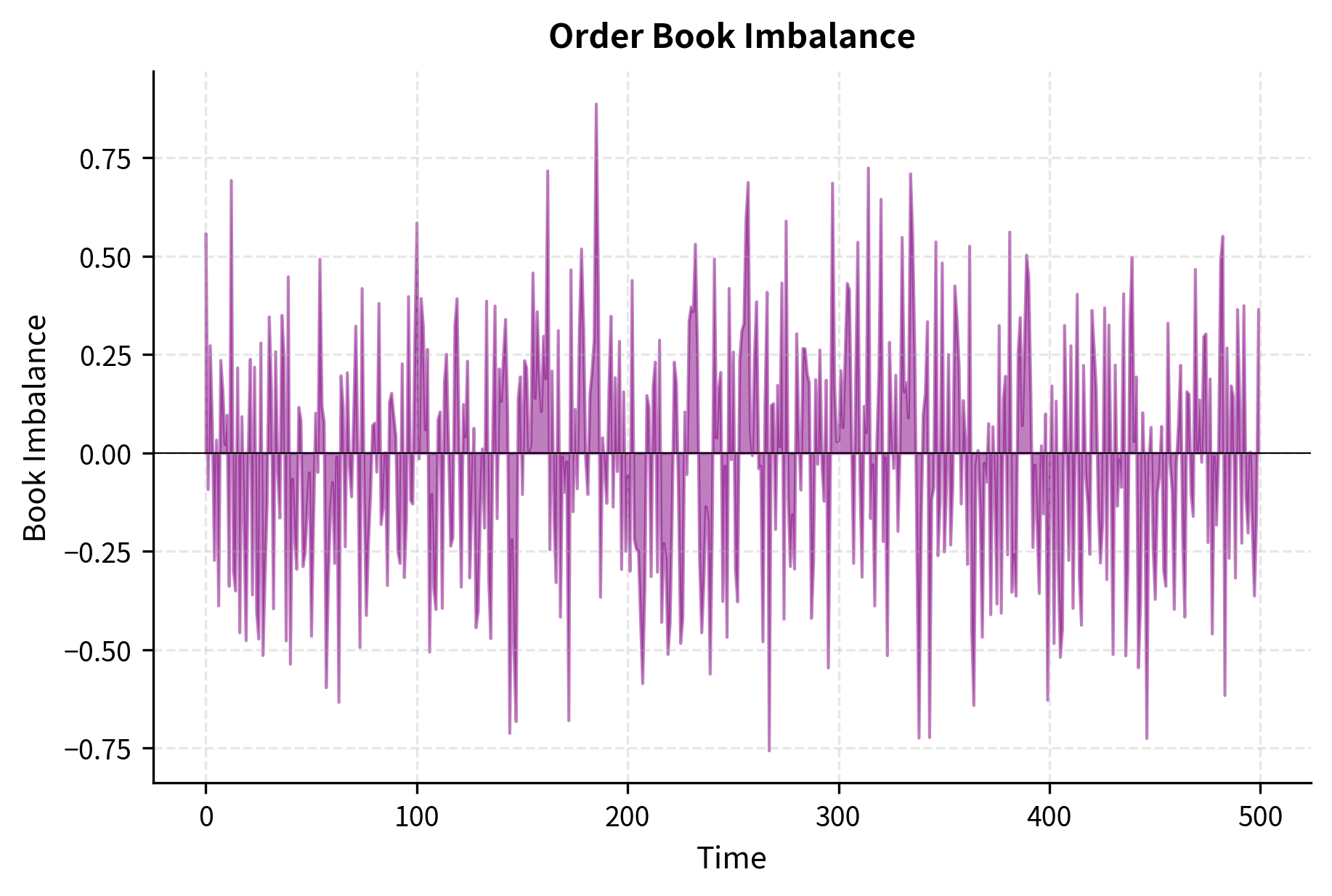

Book imbalance (or Order Book Imbalance, OBI) is a commonly studied signal in market microstructure research. The positive imbalance calculated above indicates stronger buying pressure in our simulated book, as bid volume exceeds ask volume. This metric quantifies the disparity between buying and selling pressure in the order book and can be expressed mathematically as:

Understanding this formula requires examining what each term represents and why the specific mathematical form was chosen:

- : order book imbalance, ranging from -1 to +1. The Greek letter rho is commonly used to denote this imbalance measure. A value of +1 would indicate all visible liquidity is on the bid side (maximum buying pressure), while -1 indicates all liquidity is on the ask side (maximum selling pressure). A value of zero indicates perfect balance.

- : total volume at the best bid (or top levels). This measures the depth of buying interest in the market. Larger values suggest substantial demand at current prices.

- : total volume at the best ask (or top levels). This measures the depth of selling interest. Larger values suggest substantial supply at current prices.

The formula uses a normalized difference (dividing by the sum) rather than a simple difference because this produces a bounded measure that is comparable across securities with different typical order sizes. A stock with 10,000 shares on the bid and 8,000 on the ask has the same imbalance as a stock with 100 shares on the bid and 80 on the ask: both have .

A positive indicates stronger buying pressure (more bids), while a negative value suggests selling pressure. Empirically, order book imbalance tends to predict short-term price movements: an excess of bids relative to asks often precedes price increases.

Dark Pools and Hidden Liquidity

Not all liquidity is visible in the public order book. Dark pools are private trading venues that match orders without displaying quotes publicly.

Why Dark Pools Exist

Dark pools emerged to address a fundamental tension: you might want to execute size without revealing your intentions to the market. When you need to sell $500 million of stock announcing that size would move prices against you before you can execute.

The key features of dark pools include:

- Pre-trade anonymity: Order sizes and prices are not displayed publicly

- Reduced information leakage: Other traders can't see your intentions

- Potential price improvement: Many dark pools match at the midpoint, providing better prices than the lit market

- Delayed reporting: Trades may not be reported until after execution

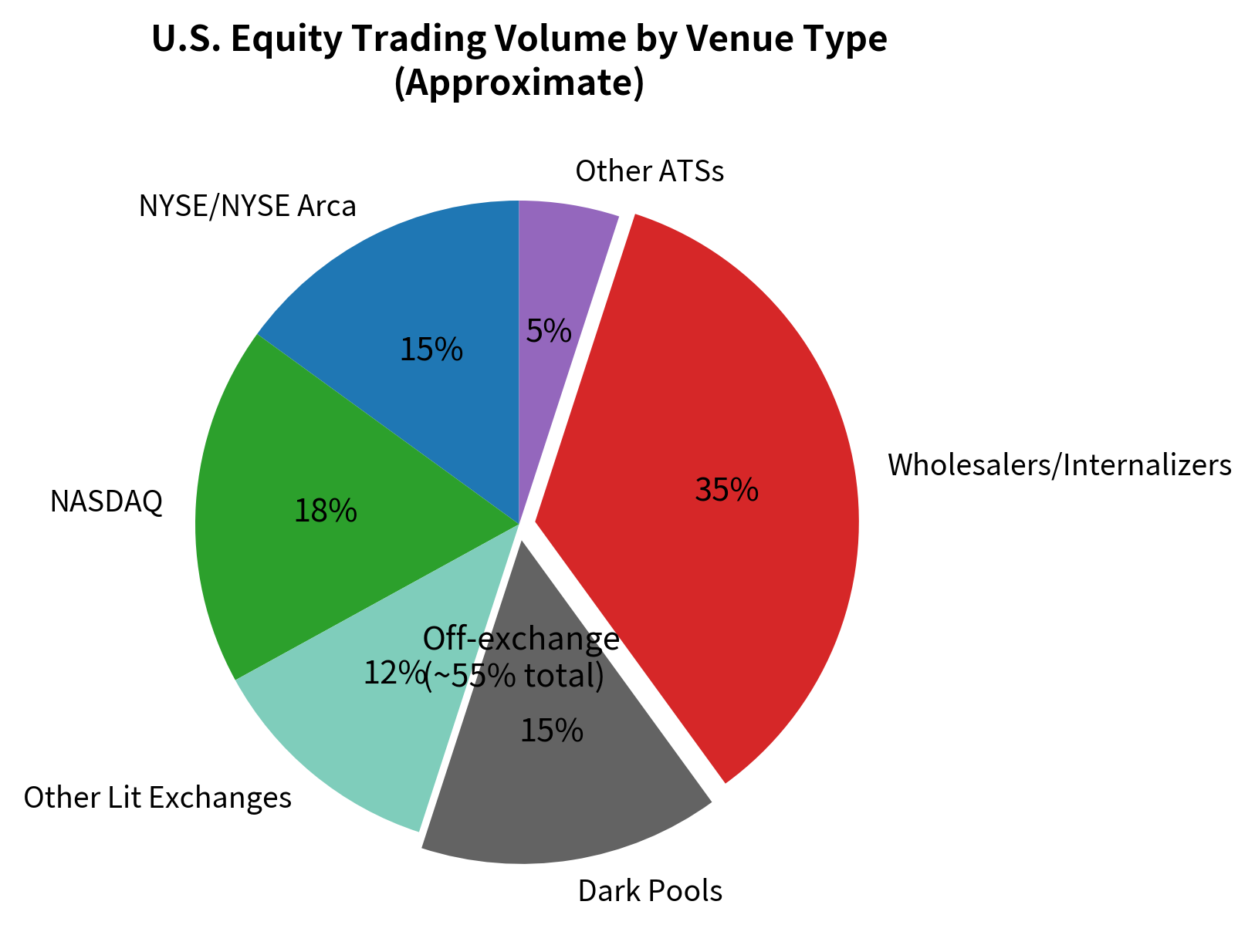

Dark Pool Market Share

Dark pools now represent a substantial portion of U.S. equity volume:

The significant share of off-exchange trading has important implications for order book analysis: the visible lit order book represents only part of the available liquidity. This is why execution algorithms often send orders to multiple venues, including dark pools, to access hidden liquidity.

Types of Dark Pool Participants

Understanding who participates in dark pools helps assess their utility:

- Block-crossing networks: Match large institutional orders, often at scheduled intervals

- Continuous dark pools: Match orders in real-time, similar to exchanges but without displayed quotes

- Broker-dealer internalization: Brokers fill customer orders against their own inventory

- Exchange dark order types: Even lit exchanges offer hidden order types

Risks of Dark Pool Trading

While dark pools offer benefits, they also carry risks:

- Adverse selection: Informed traders may selectively route to dark pools when beneficial to them

- Information leakage: Some dark pools have been found to expose order information to select participants

- Fill rate uncertainty: You may get partial or no fills, requiring lit market backup

- Gaming: Predatory traders may probe dark pools for hidden orders

Order Book Dynamics and Price Impact

The order book is not static; it evolves continuously as orders arrive, execute, and cancel. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for execution and short-term trading strategies.

Event-Driven Order Book Updates

Order book changes occur through several events:

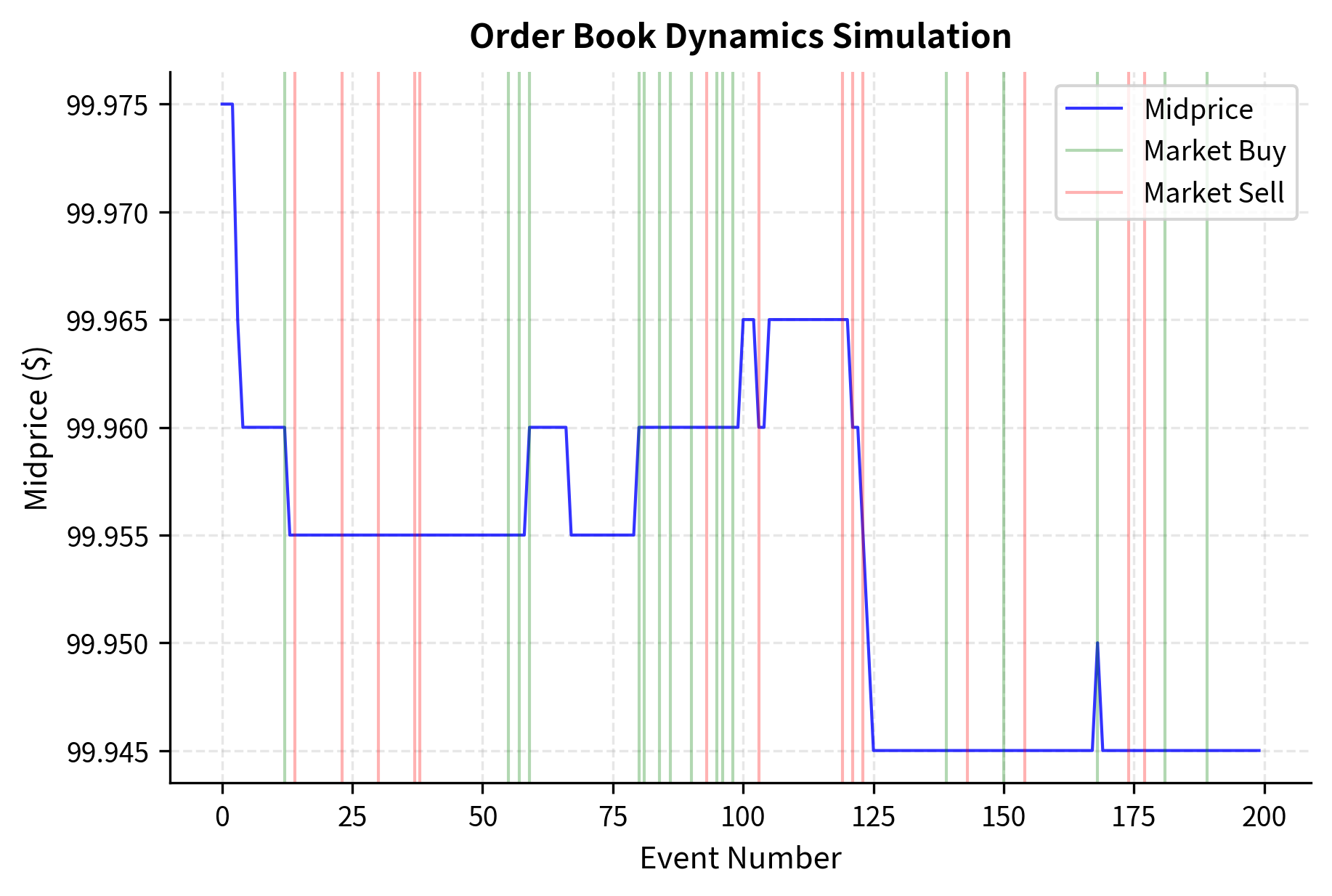

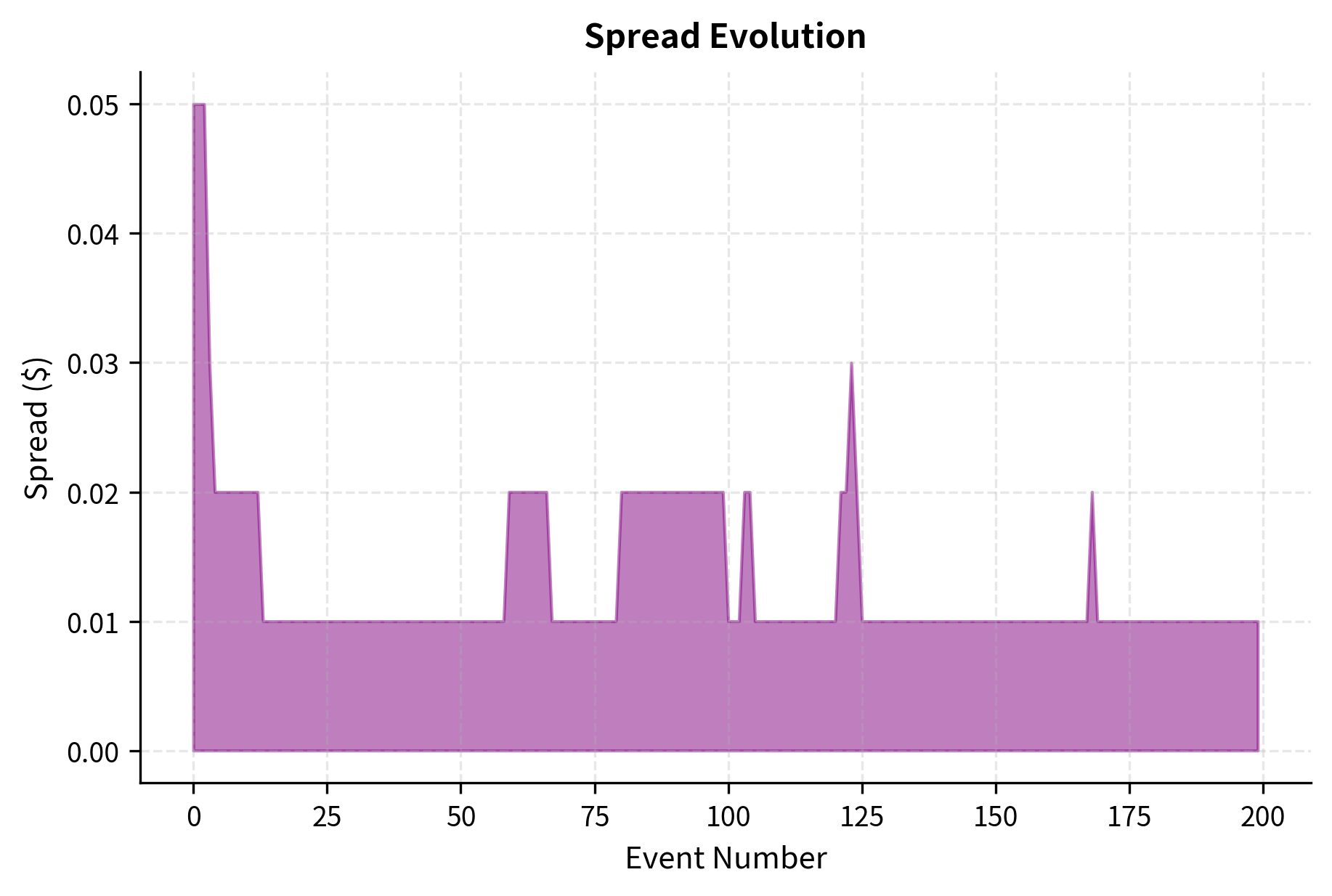

The simulation reveals several realistic patterns. Market orders cause immediate price impact (green and red vertical lines correspond to market buys and sells). The spread widens when liquidity is consumed and gradually tightens as new limit orders arrive.

Order Flow Imbalance and Price Prediction

Research in market microstructure has established that order flow imbalance (the difference between buy and sell volume) predicts short-term price movements. The intuition behind this relationship is straightforward: when more buyers than sellers are actively trading, prices tend to rise to attract additional sellers, and vice versa.

We can define the Order Flow Imbalance (OFI) over a time window as:

This formula captures the net directional pressure from actual trades. Let us understand each component:

- : Order Flow Imbalance over the time window. This is a signed quantity: positive values indicate net buying pressure, negative values indicate net selling pressure.

- : quantity of the -th trade. Larger trades contribute more to the imbalance, reflecting the greater information content and market impact of size.

- : direction of the trade (+1 for buyer-initiated, -1 for seller-initiated). A buyer-initiated trade occurs when a buyer submits a market order that executes against resting limit sell orders. A seller-initiated trade occurs when a seller's market order executes against resting limit buy orders.

- : number of trades in the window. The window choice affects signal characteristics: shorter windows capture high-frequency dynamics, while longer windows smooth out noise but may lag actual price movements.

This relationship forms the basis for many high-frequency trading strategies, as we discussed in Part VI.

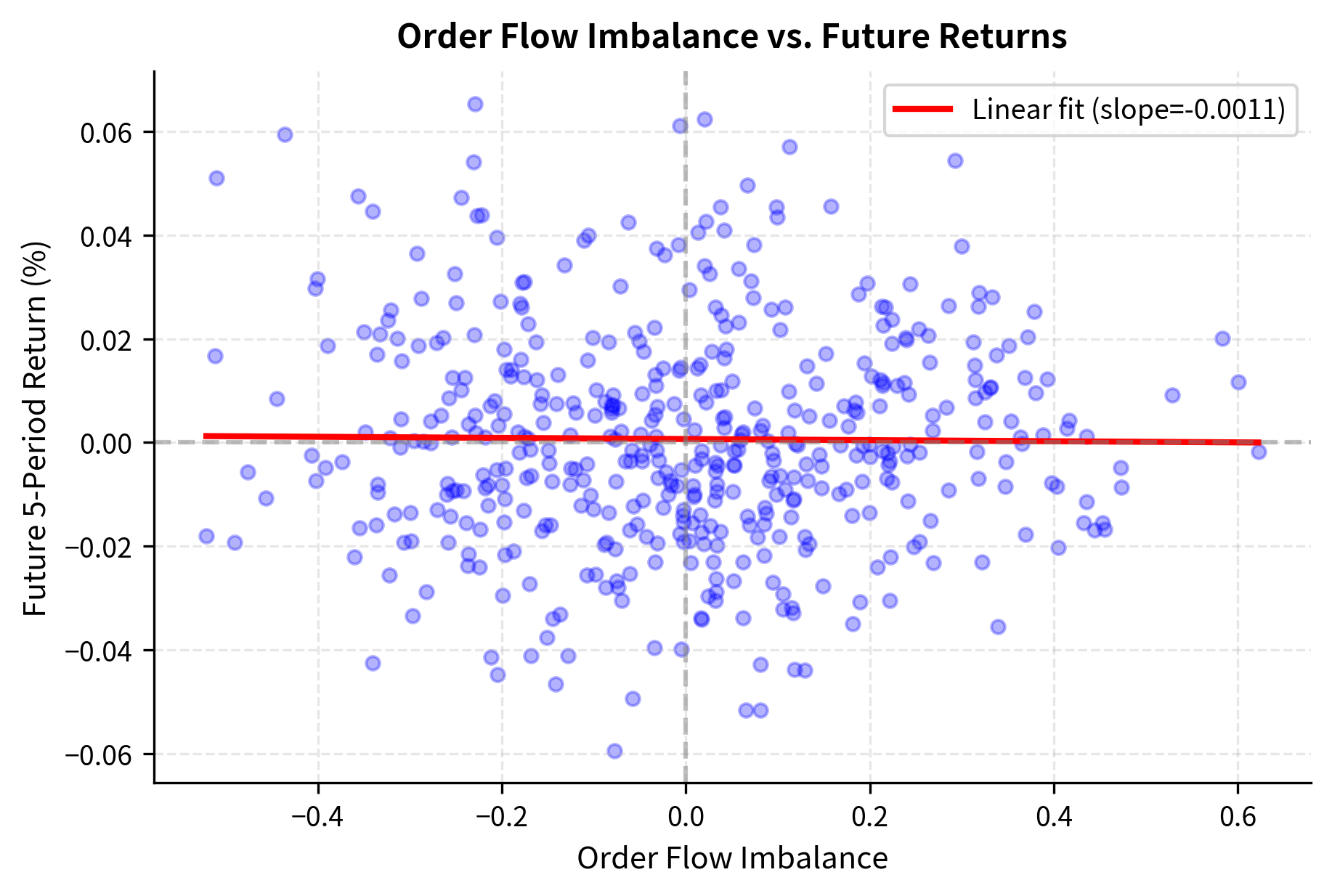

The positive slope indicates that order flow imbalance has predictive power for short-term returns. However, the relationship is noisy and exploiting it requires accounting for execution costs that may exceed the signal's value.

Market Manipulation and Regulatory Considerations

Understanding market microstructure also means recognizing when it can be exploited for manipulation. Several practices are illegal but worth knowing to recognize and avoid.

Spoofing and Layering

Spoofing is the practice of placing orders with the intent to cancel them before execution, in order to create a false impression of supply or demand and move prices.

A spoofer might place large visible bid orders to create the appearance of buying interest, causing prices to rise. They then sell into the artificially inflated price, cancel their bids, and profit from the price reversal. This practice is explicitly prohibited under the Dodd-Frank Act.

The mechanics work as follows:

- Layering bids: Place multiple large limit buy orders below the current price

- Perception manipulation: Other traders see apparent demand and buy, pushing prices up

- Execute the real trade: Sell into the higher price on the opposite side

- Cancel the layers: Remove the fake bids before they can execute

Detection algorithms look for patterns such as high order-to-trade ratios, rapid cancellations, and repetitive layering behavior.

Quote Stuffing

Quote stuffing involves submitting and canceling orders at extremely high rates to slow down exchange systems or create confusion. By overwhelming the market data feed, the manipulator may gain a latency advantage.

Wash Trading

Wash trading occurs when the same entity is on both sides of a trade, creating the false appearance of trading activity. This inflates volume statistics and can manipulate benchmarks that depend on trading volume.

Front-Running

While not always illegal depending on the context, front-running involves trading ahead of known customer orders. If a broker knows a large customer buy order is coming, trading ahead to profit from the expected price impact is prohibited.

Modern execution algorithms are designed to minimize information leakage that could enable front-running by breaking up orders and randomizing execution patterns.

Practical Analysis: Level 2 Data

Let's work through a practical example of analyzing Level 2 order book data, the type of data that you use to understand market microstructure in real-time.

Now let's compute microstructure features from this data:

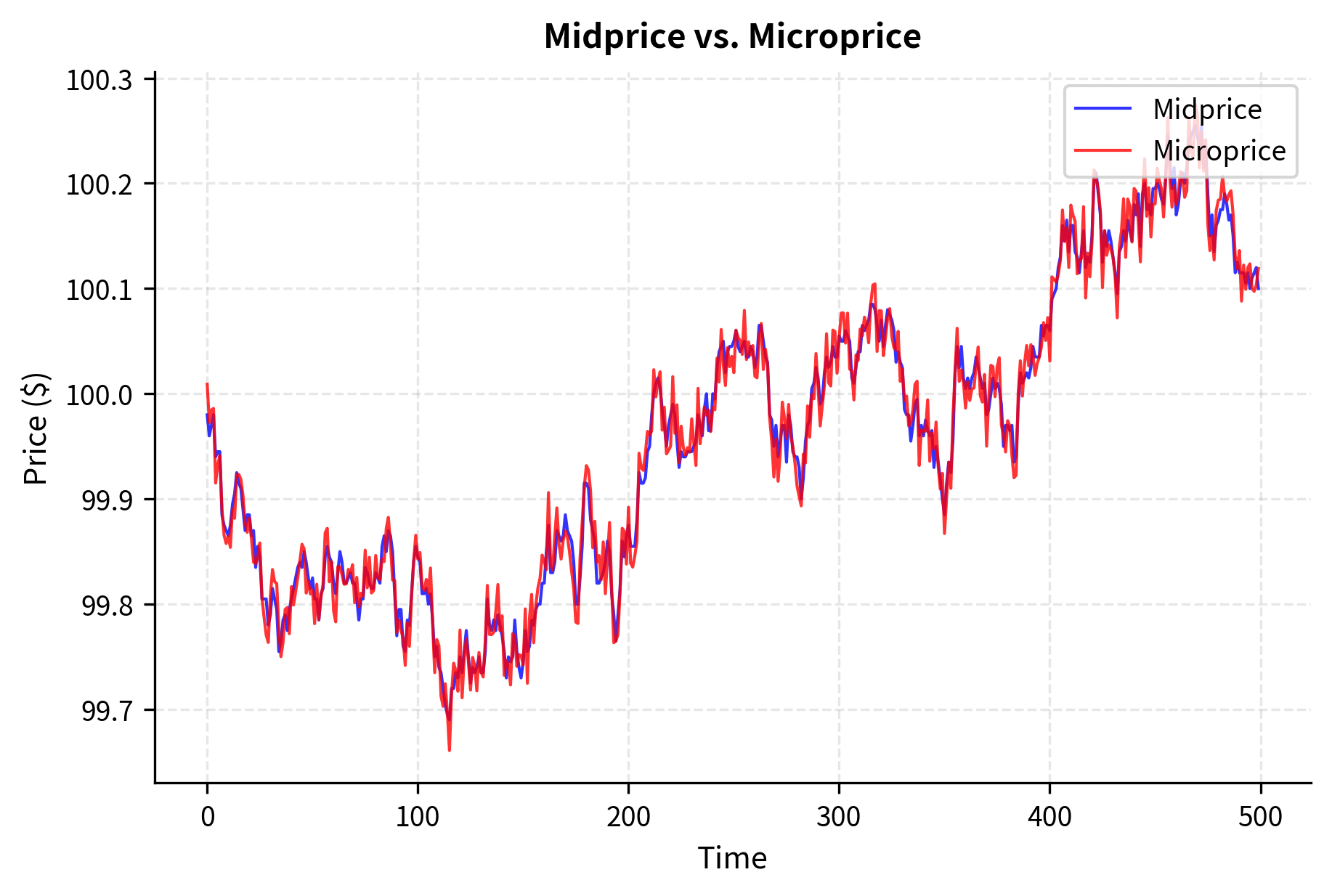

The microprice is particularly interesting: it's a depth-weighted midprice that accounts for order book imbalance. Unlike the standard midprice which treats the bid and ask symmetrically, the microprice adjusts based on available liquidity. The intuition is that prices are more likely to move toward the side with less depth, since less volume is required to push the price in that direction.

We can derive the microprice formula by thinking about it as a weighted average where the weights are the opposite side's depth. When there is more depth on the bid side, the price is more likely to move upward (toward the ask), so we weight the ask price more heavily:

Let us examine each variable to understand the economic intuition:

- : microprice. This represents a more informed estimate of the security's fair value than the simple midprice. It incorporates order book depth information that may predict short-term price movements.

- : best bid price. The highest price buyers are willing to pay.

- : best ask price. The lowest price sellers are willing to accept.

- : volume at the best bid. Represents the immediate buying liquidity. When this is large relative to the ask volume, it takes more selling to push the price down.

- : volume at the best ask. Represents the immediate selling liquidity. When this is large relative to the bid volume, it takes more buying to push the price up.

- : bid imbalance ratio, defined as . This ratio ranges from 0 to 1 and measures what fraction of top-of-book liquidity sits on the bid side.

When there's more depth on the bid side, the microprice shifts closer to the ask price, reflecting the likely direction of the next price move.

When book imbalance is positive (more bid depth), the microprice tends to be higher than the midprice, anticipating upward price pressure. This relationship forms the basis for many short-term trading signals.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Market microstructure knowledge is essential but comes with important caveats for practical application.

The most fundamental limitation is the difference between simulation and reality. Our order book models assume clean, deterministic matching rules, but real markets involve multiple venues with different rules, hidden liquidity, latency, and occasional system glitches. A strategy that performs well in a simulated order book may fail in production due to factors that weren't modeled.

Latency creates an uneven playing field. The microstructure patterns we've discussed, such as order book imbalance and microprice signals, are actively exploited by high-frequency traders with sub-millisecond execution capabilities. By the time a retail or even institutional system observes these signals and acts, the opportunity may already be gone. The alpha in microstructure signals decays extremely rapidly, often within microseconds.

Data quality presents another challenge. Level 2 data is expensive, and historical order book data even more so. Reconstructing the order book from message data requires careful handling of order IDs, message sequencing, and exchange-specific quirks. Errors in data processing can create phantom signals or miss real ones.

The regulatory environment continues to evolve. Rules around dark pools, payment for order flow, market maker obligations, and algorithmic trading change regularly. Strategies that are profitable and legal today may become prohibited tomorrow, or new regulations may create opportunities that didn't exist before. The battle between regulators and manipulators is ongoing, with detection algorithms and manipulation techniques both becoming more sophisticated.

Finally, microstructure is inherently adversarial. Every informed trader's gain comes at someone else's expense, usually the market maker or other liquidity providers. As more participants use similar signals (like order book imbalance), the signals become crowded and less profitable. The market adapts, spreads tighten, and the bar for profitable microstructure trading keeps rising.

Summary

This chapter examined the mechanics of how modern electronic markets operate at the granular level. We covered the following key concepts:

Order Book Structure: The order book is the central mechanism for price discovery and trade execution. It consists of bid and ask levels, each with price and quantity information. The spread between best bid and best ask represents the cost of immediacy.

Order Types: Market orders provide execution certainty at the cost of price uncertainty. Limit orders provide price certainty at the cost of execution uncertainty. Advanced order types like iceberg orders, IOC, FOK, and pegged orders serve specialized needs.

Order Priority: Price-time priority (FIFO) is the dominant matching scheme for equities. Queue position matters: arriving earlier at a price level provides execution priority. Pro-rata matching, used in some markets, allocates fills proportionally to order size.

Spread Components: The bid-ask spread compensates market makers for order processing costs, inventory risk, and adverse selection. Understanding these components helps explain why spreads vary across securities.

Hidden Liquidity: Dark pools and hidden order types provide venues for executing large orders with reduced information leakage. Off-exchange trading represents a substantial portion of overall volume.

Order Book Dynamics: The order book evolves continuously through order arrivals, cancellations, and trades. Order flow imbalance provides short-term predictive signals, though exploiting them requires sophisticated infrastructure.

Market Manipulation: Spoofing, layering, quote stuffing, and wash trading are prohibited practices. Understanding them helps in recognition and avoidance, and informs the design of compliant systems.

The next chapter on execution algorithms builds directly on these concepts, translating microstructure knowledge into practical algorithms for optimal order execution.

Quiz

Test your understanding of market microstructure, order types, and liquidity dynamics with this interactive quiz.

Comments