Learn FX market structure, currency forward pricing via covered interest rate parity, and hedging strategies. Master cross rates and forward valuation.

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Foreign Exchange Markets and Currency Forwards

The foreign exchange market, commonly known as forex or FX, is the largest and most liquid financial market in the world. With daily trading volumes exceeding $7.5 trillion, the FX market dwarfs equity markets by orders of magnitude. This enormous scale exists because virtually every international transaction, whether importing goods, investing abroad, or sending remittances, requires exchanging one currency for another.

Unlike the stock exchanges we examined in Chapter 1 of this part, the FX market operates as a decentralized over-the-counter (OTC) network spanning the globe. There is no single exchange or central location. Instead, trading occurs continuously through an interconnected web of banks, dealers, corporations, and electronic platforms. This structure creates a market that never sleeps: when London closes, New York is in full swing; when New York winds down, Tokyo opens.

Currency forwards extend the forward contracts we studied in earlier chapters to the FX domain. Building on the pricing frameworks from Part II, Chapters 5 and 7, we'll see how interest rate differentials between countries determine forward exchange rates through a fundamental relationship called interest rate parity. This relationship forms the backbone of global currency hedging strategies.

FX Market Structure

The foreign exchange market operates fundamentally differently from organized exchanges. Understanding its structure helps explain why FX markets exhibit unique characteristics in liquidity, pricing, and access.

The Over-the-Counter Network

The FX market is a decentralized dealer market. Major banks act as market makers, quoting bid and ask prices at which they will buy and sell currencies. These banks trade with each other in the interbank market, the core of the FX ecosystem, and with their customers: corporations, asset managers, hedge funds, and smaller banks.

The key participants in the FX market include:

- Commercial banks: The largest players, acting as dealers and market makers. Banks like JPMorgan, Citi, UBS, and Deutsche Bank dominate interbank trading.

- Central banks: Intervene to influence their domestic currency's value or manage reserves. Central bank activity can move markets significantly.

- Corporations: Engage in FX to pay for imports, convert foreign revenues, or hedge future exposures from international operations.

- Asset managers and hedge funds: Trade currencies as an asset class or hedge foreign investments. Carry trades and momentum strategies are common.

- Retail traders: Individual speculators accessing the market through brokers, typically a small fraction of total volume.

24-Hour Trading Cycle

Because major financial centers span different time zones, the FX market operates continuously from Sunday evening (when Sydney opens) through Friday evening (when New York closes), with trading following the sun around the globe.

The overlapping sessions are particularly important. The London-New York overlap (roughly 12:00-16:00 UTC) sees the highest trading volumes, as the two largest financial centers operate simultaneously. During these periods, liquidity is deepest and bid-ask spreads are typically tightest.

Spot vs. Forward Markets

The FX market divides into two primary segments based on settlement timing:

- Spot market: Transactions settle "on the spot," meaning within two business days (T+2) for most currency pairs. The spot market accounts for roughly 30% of FX turnover.

- Forward market: Transactions settle at a predetermined future date, from one week to several years ahead. Forwards, FX swaps, and currency swap together dominate FX turnover.

An FX swap combines a spot transaction with a forward transaction: buy a currency spot and simultaneously sell it forward (or vice versa). A currency swap, by contrast, involves exchanging principal and interest payments in different currencies over the life of the swap. We'll explore interest rate swaps in detail in Chapters 11 and 12.

Exchange Rate Quotes and Conventions

Understanding how exchange rates are quoted is essential before analyzing pricing relationships. FX quotes follow specific conventions that can be confusing but become intuitive with practice.

Currency Pairs and Base/Quote Convention

An exchange rate always involves two currencies: the base currency and the quote currency. An exchange rate shows how many units of the quote currency are needed to buy one unit of the base currency. This framing helps clarify the notation.

For a currency pair written as BASE/QUOTE, an exchange rate of means:

where:

- : base currency unit

- : quote currency unit

- : exchange rate (units of quote currency per unit of base currency)

For example, if EUR/USD = 1.0850, then one euro costs $1.0850 US dollars. The euro is the base currency, the dollar is the quote currency. You can think of the base currency as the "thing being priced" and the quote currency as the "unit of measurement." Just as a stock might cost $150, a euro costs $1.0850.

Currency pairs are written as BASE/QUOTE. The exchange rate tells you how much quote currency is needed to purchase one unit of base currency.

The FX market follows a hierarchy that determines which currency appears as the base. This convention evolved historically and persists today:

- EUR is always the base against other currencies (EUR/USD, EUR/GBP, EUR/JPY)

- GBP is base against all except EUR (GBP/USD, GBP/CHF)

- AUD and NZD follow, then USD

- USD is typically base against most other currencies (USD/JPY, USD/CHF, USD/CAD)

Direct vs. Indirect Quotes

From the perspective of a specific country, exchange rates can be quoted in two ways. This distinction is important because the same exchange rate information is expressed differently depending on the home currency.

- Direct quote (price quotation): Units of domestic currency per one unit of foreign currency

- Indirect quote (volume quotation): Units of foreign currency per one unit of domestic currency

If you are a US-based investor:

- EUR/USD = 1.0850 is a direct quote (dollars per euro)

- USD/JPY = 150.25 is an indirect quote (yen per dollar, inverted to get dollars per yen)

These calculations illustrate how the direct quote is the reciprocal of the indirect quote. For the USD/JPY pair, 150.25 yen per dollar equates to approximately $0.0067 per yen. This reciprocal relationship means knowing one quote immediately gives you the other.

Bid-Ask Spreads

Like all traded instruments, currency pairs have bid and ask prices. The bid is the price at which dealers will buy the base currency (you sell), and the ask is the price at which dealers will sell (you buy). This distinction matters because you always transact at the less favorable price for your side of the trade.

For EUR/USD quoted as 1.0848/1.0852:

- Bid = 1.0848: Dealer buys euros, you receive $1.0848 per euro

- Ask = 1.0852: Dealer sells euros, you pay $1.0852 per euro

The spread (0.0004 or 4 "pips") represents the dealer's profit margin and varies by currency pair liquidity, volatility, and market conditions. Highly liquid pairs like EUR/USD have narrow spreads, while exotic currency pairs can have spreads that are many times larger.

A pip is the smallest standard price movement in an FX quote. For most pairs, it's 0.0001 (fourth decimal place). For JPY pairs, it's 0.01 (second decimal place) due to the yen's lower value per unit.

Major pairs like EUR/USD typically trade with 1-4 pip spreads during liquid hours. Emerging market currencies can have spreads of 50-100 pips or more.

Cross Rates

A cross rate is an exchange rate between two currencies that doesn't involve USD, calculated from each currency's rate against the dollar. Cross rates are essential when you need to exchange between two non-USD currencies. Because the US dollar serves as the world's primary reserve and trading currency, most FX transactions involve the dollar on one side. When you need to exchange euros for Japanese yen, however, you need to determine the appropriate cross rate.

Calculating Cross Rates

Given two exchange rates involving USD, you can derive the cross rate between the other two currencies. This calculation ensures that consecutive conversions are equivalent to a direct conversion. In other words, converting euros to dollars and then dollars to yen must yield the same result as a direct euro-to-yen exchange at the proper cross rate.

If you know EUR/USD and USD/JPY, you can find EUR/JPY:

where:

- : cross rate (Yen per Euro)

- : exchange rate of USD per EUR

- : exchange rate of JPY per USD

To understand why this multiplication works, consider the dimensional analysis. We want to find yen per euro, and we can trace through the currency units step by step:

The USD units cancel in the multiplication, leaving yen per euro. Canceling intermediate currency units is the basis for cross rate calculations.

When both rates have USD as the quote currency (e.g., EUR/USD and GBP/USD), the calculation requires division rather than multiplication. To calculate GBP/EUR:

- : implied cross rate (Euros per Pound)

- : exchange rate of USD per GBP

- : exchange rate of USD per EUR

We can verify the units cancel correctly by treating the exchange rates as fractions of units. Dimensional analysis confirms the formula:

Since the pair GBP/EUR is defined as Euros per Pound, the derived units match perfectly.

The calculated cross rate of 0.8579 EUR/GBP indicates that one Euro purchases roughly 0.86 Pounds, consistent with the direct EUR/USD and GBP/USD rates. This internal consistency is maintained by arbitrageurs who continuously monitor cross rates and exploit any deviations.

### Cross Rate Arbitrage

In efficient markets, cross rates derived from USD pairs should equal directly quoted cross rates. If they don't, an arbitrage opportunity exists. This arbitrage keeps FX markets consistent and prevents pricing contradictions.

Triangular arbitrage exploits inconsistencies among three exchange rates. You start with one currency, convert through two others, and return to the original, earning a risk-free profit if the rates are misaligned.

Consider this triangular arbitrage example: if derived EUR/JPY differs from the quoted EUR/JPY, you can profit by executing a series of trades that takes advantage of the mispricing. The strategy works as follows:

- Starting with USD

- Converting to EUR at the spot rate

- Converting EUR to JPY at the (mispriced) EUR/JPY rate

- Converting JPY back to USD

- If you end with more USD than you started, you've captured the arbitrage

This arbitrage requires no capital commitment and no risk, only the ability to execute three trades simultaneously. The profit is locked in at initiation.

In Case 2, the calculated profit of approximately ${{python} f'{profit_2:,.0f}'} confirms that when the market forward rate exceeds the implied rate, a risk-free arbitrage is possible. In practice, electronic trading systems identify and eliminate such arbitrage opportunities within milliseconds, keeping cross rates aligned. The speed of modern algorithmic trading means these opportunities rarely persist long enough for manual traders to exploit them.

Interest Rate Parity

Interest rate parity (IRP) is the fundamental relationship connecting spot exchange rates, forward exchange rates, and interest rates across countries. It explains why currencies with higher interest rates tend to trade at forward discounts. Understanding this relationship is essential because it reveals why forward rates are not forecasts of future spot rates but rather mathematical consequences of interest rate differentials.

The No-Arbitrage Argument

A simple thought experiment explains interest rate parity. Consider a situation where you have $1 to invest for a period (in years). You have two strategies available, each starting with the same capital and ending at the same future date. For markets to be in equilibrium, both strategies must produce identical returns, otherwise arbitrage would be possible.

Strategy A: Invest domestically

- Invest in a US dollar deposit earning (domestic rate)

- After period : dollars

This is the straightforward approach. You keep your money in dollars and earn the US interest rate.

Strategy B: Invest abroad

- Convert dollars to euros at spot rate (USD per EUR, so you get euros)

- Invest in a euro deposit earning (foreign rate)

- Lock in a forward contract to convert back to dollars at forward rate

- After period : dollars

This alternative path requires more steps but, crucially, involves no exchange rate risk because the forward contract locks in the conversion rate for the return journey.

For no arbitrage, both strategies must yield the same return. If they didn't, investors would pile into the superior strategy, driving rates until equality was restored. By equating the returns and solving for , we derive the fundamental pricing relationship:

- : forward exchange rate

- : spot exchange rate (domestic per foreign)

- : domestic interest rate

- : foreign interest rate

- : time to maturity in years

This is the covered interest rate parity (CIP) condition. The word "covered" refers to the fact that exchange rate risk is eliminated (covered) by the forward contract.

Covered interest rate parity states that the forward exchange rate must equal the spot rate adjusted for the interest rate differential between two currencies. When the forward is locked in, exchange rate risk is "covered," hence the name.

Forward Premium and Discount

The relationship between spot and forward rates is expressed as:

where:

- : forward exchange rate

- : spot exchange rate

- : domestic interest rate

- : foreign interest rate

- : time to maturity in years

This formula has important implications for understanding currency markets. When , the forward rate , meaning the foreign currency trades at a forward premium (it will be worth more in terms of domestic currency in the forward market than spot). Intuitively, this makes sense: if you can earn more interest in the domestic currency, the market compensates by making the foreign currency relatively more valuable in forward transactions.

Conversely, when , the forward rate , meaning the foreign currency trades at a forward discount. The higher foreign interest rate is offset by expected currency depreciation embedded in the forward rate.

The forward premium or discount can be annualized to express it as a comparable rate:

where:

- : forward exchange rate

- : spot exchange rate

- : number of days to forward settlement

- : the percentage return (yield) locked in by the forward contract

- : scaling factor to convert the period return to an annualized rate

The annualization allows comparison across different tenor forwards and against interest rate differentials.

Since US rates exceed eurozone rates, the euro trades at a forward premium; it costs more dollars to buy euros forward than spot. This makes intuitive sense: if you can earn more investing in dollars, the forward rate compensates by making the euro relatively more expensive in the future. The market is essentially saying that earning the higher US rate is exactly offset by paying more for euros when the forward matures.

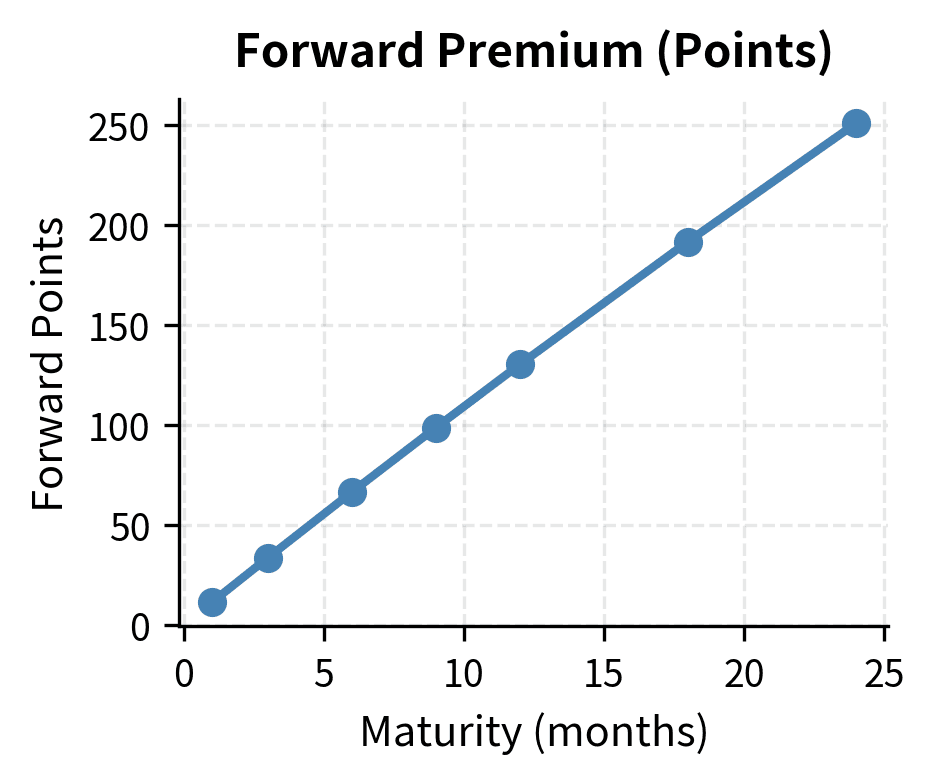

Forward Points

In practice, forward rates are often quoted as "forward points," the difference between the forward rate and spot rate, multiplied by 10,000 (for most pairs) or 100 (for JPY pairs). This convention exists because forward points change more frequently than spot rates and allow dealers to quote forward adjustments without constantly updating full prices.

The calculated value of {python} f'{forward_points:+.1f}' points means the 3-month forward rate is approximately {python} f'{forward_points:.0f}' pips (or points) above the spot rate. Positive forward points indicate a forward premium on the base currency, while negative points indicate a forward discount.

Covered Interest Arbitrage

When CIP is violated, arbitrage opportunities arise. The arbitrage mechanism ensures CIP holds in well-functioning markets. Understanding how to construct and execute this arbitrage reveals why the interest rate parity relationship is so robust.

Suppose the forward rate is "too high" relative to CIP (i.e., the euro is overpriced in the forward market). You can exploit this mispricing through the following sequence of transactions:

- Borrow dollars at

- Convert to euros at spot rate

- Invest euros at

- Sell euros forward at the (overpriced) rate

- At maturity: receive euros, convert to dollars, repay dollar loan

- Pocket the risk-free profit

This arbitrage is "covered" because the forward contract eliminates exchange rate risk. You know exactly how many dollars you will receive when you convert your euro proceeds at maturity.

The positive profit in Case 2 confirms that when the market forward rate is higher than the theoretical CIP rate, a risk-free arbitrage is possible by borrowing domestic currency and investing in the foreign currency. The arbitrage activity itself pushes rates back toward equilibrium: borrowing pressure raises domestic rates, selling euros forward pushes the forward rate down, until no profit remains.

### Uncovered Interest Parity

While covered interest parity uses forward contracts to eliminate exchange rate risk, **uncovered interest parity (UIP)** makes a prediction about future spot rates based on economic theory rather than arbitrage:

$$

E[S_T] = S \times \frac{1 + r_d \times T}{1 + r_f \times T}

$$

where:

- $E[S_T]$: expected future spot rate

- $S$: current spot exchange rate

- $r_d$: domestic interest rate

- $r_f$: foreign interest rate

- $T$: time to maturity in years

UIP states that the expected future spot rate equals the current forward rate. In other words, high-yielding currencies are expected to depreciate against low-yielding currencies, exactly offsetting the interest rate advantage. The intuition is that if a currency offered both higher interest rates and appreciation, capital would flood in until one or both advantages disappeared.

Unlike CIP (which is a no-arbitrage condition and holds tightly), UIP is an equilibrium hypothesis that doesn't hold well empirically. The "forward premium puzzle" refers to the finding that high-yield currencies tend to appreciate rather than depreciate, contrary to UIP. This anomaly underlies the popular "carry trade" strategy, where investors borrow low-yielding currencies to invest in high-yielding ones, profiting from both the interest differential and (often) favorable currency movements.

## Currency Forwards for Hedging

Currency forwards are powerful tools for managing foreign exchange exposure. You must understand how to construct and value these hedges.

### Types of FX Exposure

Organizations face several types of currency risk:

- transaction exposure: Risk from known future foreign currency cash flows (e.g., a US importer paying €1 million to a German supplier in 60 days)

- translation exposure: Risk from converting foreign subsidiary financial statements to the parent's reporting currency

- economic exposure: Long-term competitive risk from exchange rate changes affecting future revenues and costs

Currency forwards directly hedge transaction exposure and can partially address economic exposure.

### Forward Contract Mechanics

A currency forward obligates two parties to exchange currencies at a predetermined rate on a future date. Building on our discussion of forwards in Chapter 5 of this part, the key terms include:

- Notional amount: The quantity of currency to be exchanged

- Forward rate: The agreed exchange rate

- Settlement date: When the exchange occurs

- Settlement method: Physical delivery or cash settlement

### Hedging Example: US Investor with Euro Assets

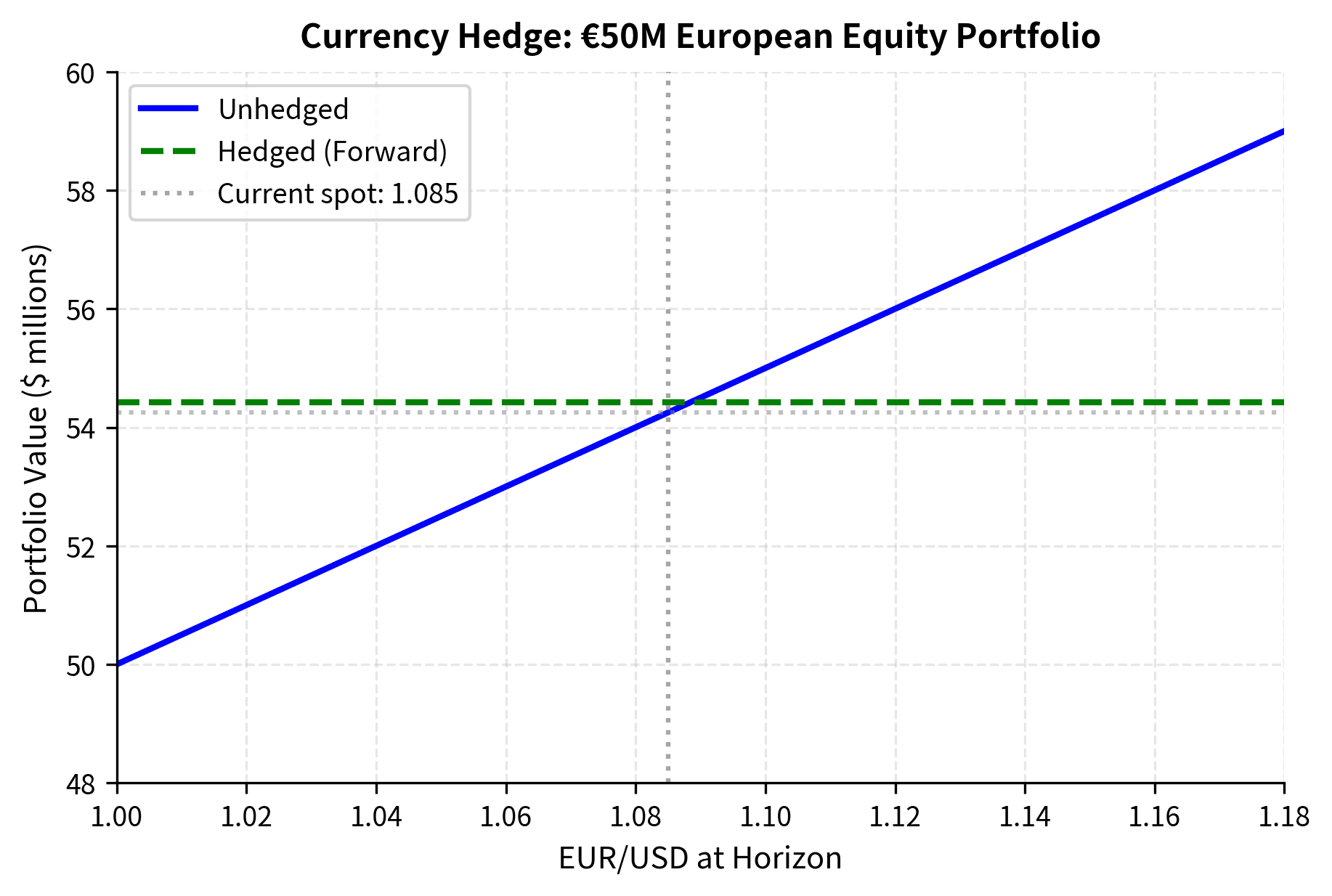

Consider a US pension fund that owns €50 million in European equities. You are bullish on European stocks but want to eliminate currency risk: you want returns driven by stock performance, not EUR/USD fluctuations.

The hedge locks in the forward rate, eliminating both downside and upside currency exposure. The unhedged portfolio benefits if EUR strengthens but suffers if EUR weakens.

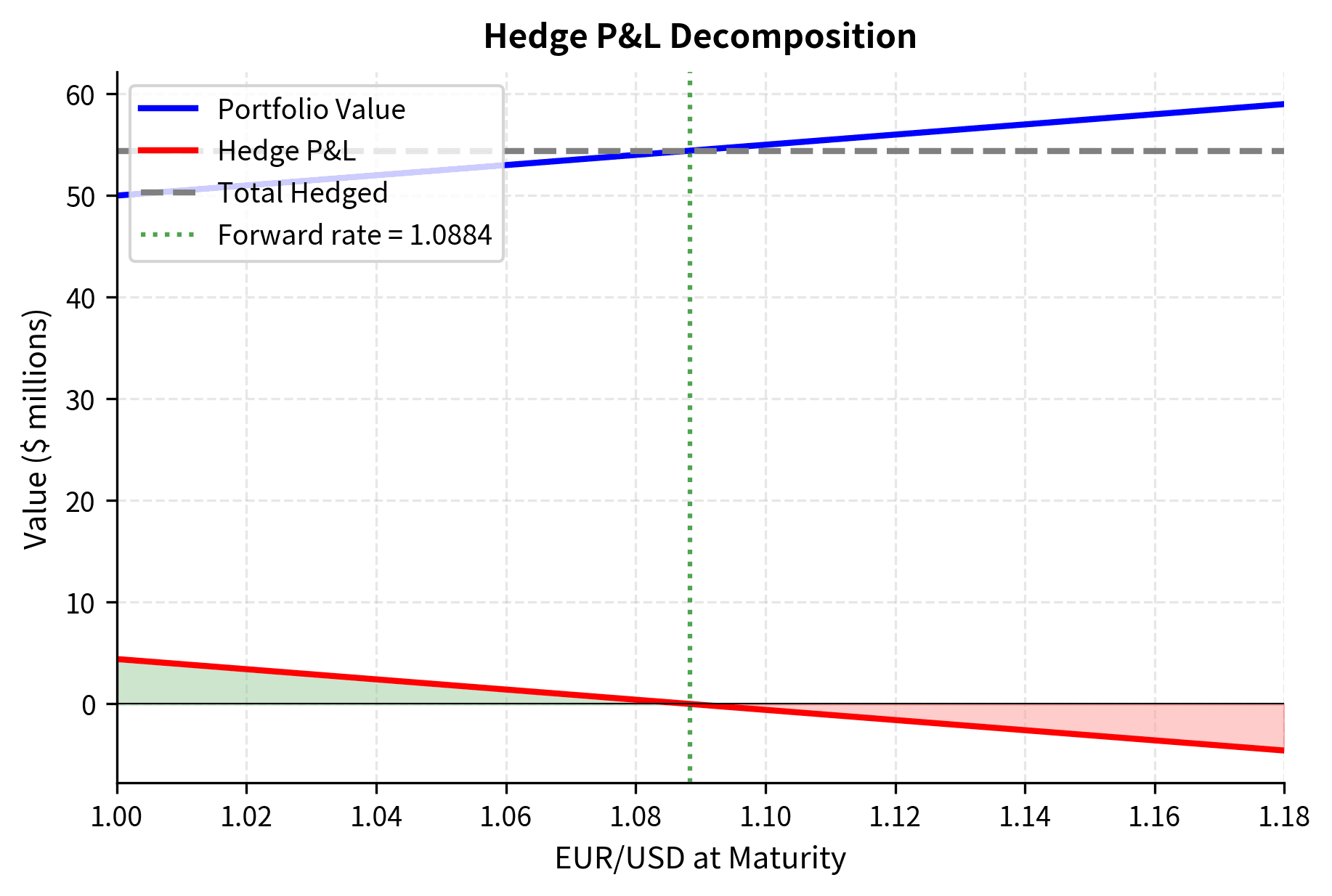

Calculating Hedge P&L

At the forward's maturity, the hedge generates a profit or loss that offsets currency movements in the underlying portfolio. The profit and loss calculation is straightforward: compare what you locked in to what you would have received at the prevailing spot:

where:

- : notional amount of foreign currency

- : locked-in forward rate

- : spot exchange rate at maturity

- : gain or loss per unit of currency (for a short forward position)

For a short forward position (selling foreign currency forward), the interpretation is intuitive: you agreed to sell at rate , but the market rate at maturity is . If , you sold at a higher rate than you could have gotten in the spot market, generating a profit. If , you sold at a lower rate than the spot market, creating a loss. This gain or loss exactly offsets the currency impact on your underlying foreign asset.

Notice that regardless of where EUR/USD ends up, the total hedged position is always approximately €50M × {python} f'{forward_rate:.4f}' = ${{python} f'{(euro_notional * forward_rate / 1e6):.2f}'}M. The hedge P&L exactly offsets currency gains or losses. When the euro weakens, the portfolio loses value but the hedge generates a profit. When the euro strengthens, the portfolio gains value but the hedge generates a loss. The net result is always the locked-in forward rate.

Rolling Hedges

For ongoing exposures, hedging typically involves rolling forward contracts. At each maturity, the old forward settles and a new one is initiated. Rolling creates "roll yield" that depends on the forward curve:

- Positive carry: If you're receiving the higher-yielding currency forward, each roll adds value

- Negative carry: If you're paying the higher-yielding currency forward, each roll costs

This cost represents the price of eliminating currency risk. Whether it's worth paying depends on your risk tolerance and views on EUR/USD.

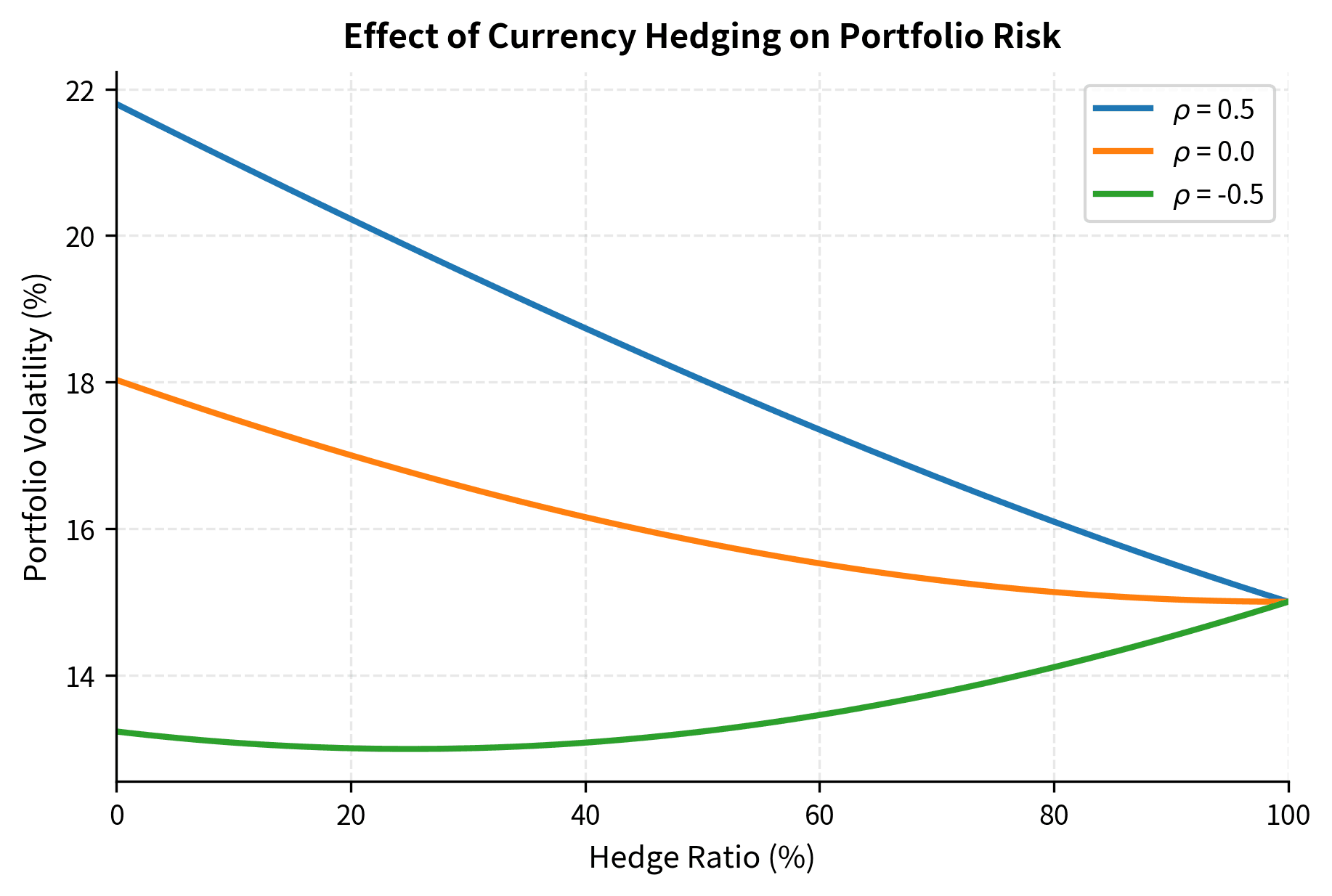

Optimal Hedge Ratios

A 100% hedge eliminates currency risk but also forgoes potential gains from favorable moves. Some investors use partial hedges based on:

- Volatility targeting: Hedge enough to achieve a target portfolio volatility

- Mean-variance optimization: Balance expected return against risk reduction

- Regime-dependent: Adjust hedge ratio based on market conditions

The volatility of a partially hedged portfolio derives from the variance of the sum of the equity position and the remaining currency exposure. A partially hedged portfolio has two sources of risk: the underlying asset and the unhedged portion of currency exposure. To calculate the portfolio volatility, we first determine the variance of the sum of these components:

where:

- : portfolio volatility

- : volatility of the underlying asset

- : volatility of the exchange rate

- : hedge ratio ()

- : correlation between asset returns and exchange rate returns

- : variance contribution from the unhedged portion of currency exposure

- : covariance term capturing the diversification effect between asset and currency returns

The covariance term is particularly important because it captures the diversification effect. When equity and currency returns are negatively correlated, the covariance term is negative, reducing total portfolio variance. This means the currency exposure provides a natural hedge against equity risk.

When equity returns and currency returns are negatively correlated (ρ < 0), the currency provides a natural hedge, and adding a forward hedge can actually increase total volatility at low hedge ratios. This counterintuitive result illustrates why understanding correlations is crucial for hedge design. A blanket policy of fully hedging all currency exposure may not be optimal if currencies naturally offset other portfolio risks.

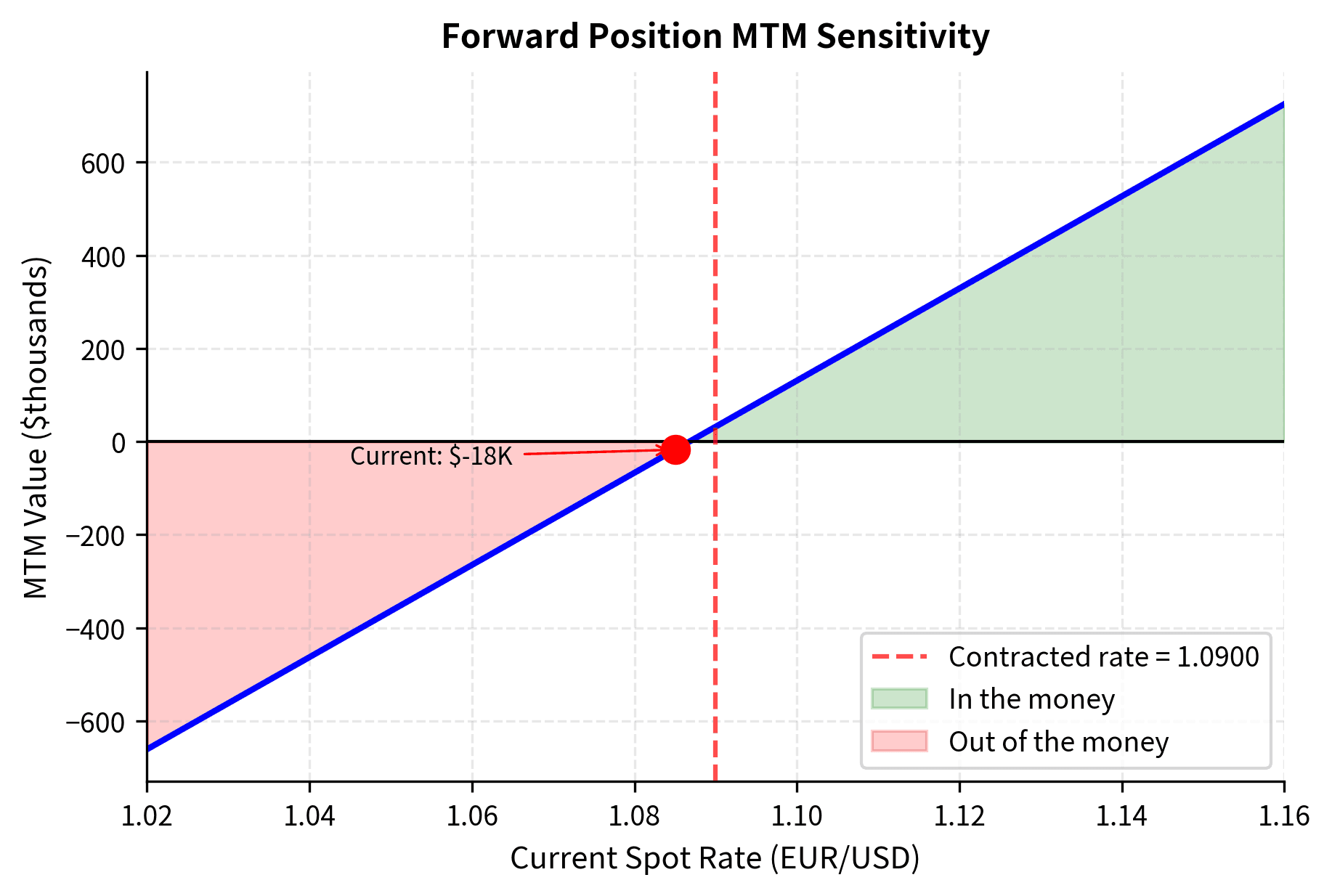

Mark-to-Market Valuation of Currency Forwards

As we discussed for forwards generally in Chapter 5, currency forwards must be marked to market as exchange rates and interest rates change. The value of an existing forward position depends on how current market rates compare to the contract rate. This valuation is essential for risk management, financial reporting, and understanding the economic exposure of forward positions.

Forward Valuation Formula

For a forward contract to buy foreign currency at rate with time remaining, the current value to the buyer is:

where:

- : current value of the forward position in domestic currency

- : notional amount of foreign currency

- : current forward rate for maturity

- : contracted forward rate

- : domestic interest rate

- : time remaining to settlement in years

This formula calculates the present value of the difference between the current forward rate and the contracted rate. The term represents the future gain or loss per unit of currency: if the current forward rate exceeds the contracted rate, the position has gained value because you locked in the right to buy at a lower rate than the market now offers. Dividing by discounts this future amount to the present using the domestic interest rate, because the gain or loss will only be realized at the forward's maturity.

The forward is underwater because we agreed to pay {python} f'{contracted_rate:.4f}' for euros, but the current forward is only {python} f'{current_forward:.4f}'. We're locked into paying more than the market rate. This negative mark-to-market value represents an economic liability that would need to be paid if the position were closed out today.

Practical Considerations

Implementing currency hedging in practice involves considerations beyond pure pricing theory.

Transaction Costs

Currency forwards traded with banks carry costs embedded in:

- Bid-ask spreads: Wider for longer tenors and less liquid currency pairs

- Credit charges: Banks may require collateral or charge for counterparty risk

- Operational costs: Settlement, documentation, and ongoing monitoring

If you are a corporate treasurer hedging €100 million over one year, these costs might amount to 0.10-0.25% annually for major currency pairs.

Hedge Accounting

Accounting standards (IFRS 9, ASC 815) allow companies to designate forwards as hedges, avoiding P&L volatility from mark-to-market changes. However, hedge accounting requires:

- Formal documentation at inception

- Prospective and retrospective effectiveness testing

- Specific designation of hedged items and risks

Many corporates maintain detailed hedge documentation to qualify for favorable accounting treatment.

CIP Violations: The Cross-Currency Basis

While covered interest parity is a no-arbitrage condition that should hold exactly, persistent deviations called the "cross-currency basis" emerged during the 2008 financial crisis and have continued since. These deviations challenge classical financial theory and have practical implications.

The cross-currency basis represents the spread that must be added to (or subtracted from) the theoretical forward to match market prices:

where:

- : observed market forward rate

- : spot exchange rate

- : domestic interest rate

- : foreign interest rate

- : cross-currency basis spread

- : time to maturity in years

A negative basis in EUR/USD means dollar funding via FX swaps is more expensive than direct dollar borrowing, a reflection of dollar scarcity and bank balance sheet constraints. When global demand for dollars increases, particularly during periods of financial stress, the basis widens as market participants pay a premium to access dollars through the FX swap market.

The negative basis calculated here indicates that the market forward rate is higher than the theoretical rate implied by CIP. This suggests that dollar funding via FX swaps is effectively more expensive than direct borrowing. The cross-currency basis is a critical consideration for international investors and is closely watched by central banks as an indicator of dollar funding stress.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for currency forward pricing and valuation are:

- S: Current spot exchange rate (domestic per foreign). The base variable for all currency derivatives.

- F: Forward exchange rate. Determined by interest rate parity conditions.

- r_d: Domestic interest rate. Used in the numerator of the IRP formula.

- r_f: Foreign interest rate. Used in the denominator of the IRP formula.

- T: Time to settlement in years. Scales the interest rates.

- K: Contracted forward rate. The rate agreed upon in the forward contract, used for mark-to-market valuation.

- N: Notional amount of the contract. The principal amount exchanged.

Limitations and Considerations

Currency forward hedging, while powerful, comes with important limitations that practitioners must understand.

Hedging eliminates both downside and upside. A fully hedged position cannot benefit from favorable currency movements. If you believe you have skill in forecasting currencies, or if you simply want exposure to currency as an asset class, full hedging may not be appropriate. The decision to hedge involves balancing risk reduction against the cost of forgone potential gains and the direct costs of implementing the hedge.

Forward hedging addresses transaction risk but not economic risk. If you are a manufacturer with ongoing foreign currency revenues, you face economic exposure that simple forward contracts cannot fully address. If EUR/USD moves permanently lower, the company's competitive position changes in ways that one-year rolling forwards cannot hedge. Managing economic exposure often requires operational changes, such as relocating production, adjusting pricing, or sourcing inputs differently, rather than purely financial hedges.

Counterparty risk exists in OTC markets. Unlike exchange-traded futures, currency forwards are bilateral OTC contracts. If your counterparty defaults, you may be left unhedged at the worst possible time (when markets have moved against your counterparty). Post-2008 reforms requiring central clearing and margin for many derivatives have reduced but not eliminated this risk.

Rolling hedges can be expensive in certain rate environments. When interest rate differentials are large and persistent, the cumulative cost of rolling forward hedges can significantly erode returns. If you hedge exposure to a high-yielding emerging market currency, you might pay 5-10% annually in roll costs, fundamentally changing the risk-return profile of the investment.

Summary

The foreign exchange market is a vast, decentralized network that operates continuously across global time zones, processing over $7.5 trillion in daily transactions. Key concepts from this chapter include:

-

Currency pair conventions: Exchange rates are quoted as BASE/QUOTE, telling you how many quote currency units buy one base currency unit. Understanding bid-ask spreads and pip calculations is essential for FX trading.

-

Cross rates: When trading between two non-USD currencies, cross rates are calculated from each currency's rate against the dollar, ensuring no triangular arbitrage opportunities exist in efficient markets.

-

Covered interest rate parity (CIP): The forward exchange rate is determined by the spot rate and the interest rate differential between two currencies: . This no-arbitrage relationship ensures that investing domestically and investing abroad with a forward hedge yield identical returns.

-

Forward premium and discount: Currencies with lower interest rates trade at forward premiums, while currencies with higher interest rates trade at forward discounts, reflecting the interest rate differential.

-

Currency hedging: Forward contracts allow you to lock in exchange rates for future transactions, eliminating currency risk from international exposures. The hedge P&L offsets gains or losses in the underlying position.

-

Practical considerations: Real-world hedging involves transaction costs, hedge accounting requirements, and cross-currency basis deviations from theoretical CIP. The decision to hedge involves balancing risk reduction against costs and forgone potential gains.

Building on the forward pricing frameworks from earlier chapters, currency forwards represent one of the most widely used derivative instruments globally. In upcoming chapters, we'll explore options, which unlike forwards, allow hedgers to eliminate downside risk while retaining upside potential, and interest rate swaps, which extend these hedging concepts to fixed income markets.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about foreign exchange markets and currency forwards.

Comments