Master sentence boundary detection in NLP, covering the period disambiguation problem, rule-based approaches, and the unsupervised Punkt algorithm. Learn to implement and evaluate segmenters for production use.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Sentence Segmentation

Splitting text into sentences sounds trivial. Just look for periods, right? But consider this: "Dr. Smith earned $3.5M in 2023. He works at U.S. Steel Corp." That single paragraph contains four periods, but only one marks a true sentence boundary. The others appear in abbreviations, numbers, and company names. Sentence segmentation, also called sentence boundary detection, is the task of identifying where one sentence ends and another begins.

Why does this matter for NLP? Sentences are fundamental units of meaning. Machine translation systems translate sentence by sentence. Summarization algorithms need to extract complete sentences. Sentiment analysis often operates at the sentence level. Get the boundaries wrong, and downstream tasks inherit corrupted input.

This chapter explores why periods lie, how rule-based systems attempt to disambiguate them, and how the Punkt algorithm uses unsupervised learning to detect sentence boundaries without hand-crafted rules. You'll implement segmenters from scratch and learn to evaluate their performance.

The Period Disambiguation Problem

The period character (.) serves multiple functions in written text. Only one of those functions marks a sentence boundary:

- Sentence terminator: "The cat sat on the mat."

- Abbreviation marker: "Dr. Smith", "U.S.A.", "etc."

- Decimal point: "3.14159", "$19.99"

- Ellipsis component: "Wait... what?"

- Domain/URL separator: "www.example.com"

- File extension: "document.pdf"

Sentence boundary detection (SBD) is the task of identifying the positions in text where one sentence ends and the next begins. It is also called sentence segmentation or sentence splitting.

Let's examine how often periods actually end sentences in typical text:

The breakdown reveals a striking pattern:

| Period Type | Count | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations | ~11 | Dr., Ph.D., U.S., A.I., M.L., N.I.H., approx. |

| Sentence endings | ~4 | True boundaries |

| URLs/emails | ~4 | www.energy.gov, j.smith@energy.gov |

| Decimal points | ~2 | 2.5M |

Only about 20% of periods mark actual sentence boundaries. A naive approach that splits on every period would produce catastrophically wrong output, creating false boundaries at abbreviations, decimal numbers, and URLs.

Abbreviations: The Primary Challenge

Abbreviations cause the most trouble because they're common and varied. Some end sentences, others don't:

The same abbreviation ("U.S.") can appear mid-sentence or at a sentence boundary. Context matters enormously. A period after an abbreviation might end a sentence if followed by a capital letter, but capital letters also start proper nouns mid-sentence.

Question Marks and Exclamation Points

Sentence-ending punctuation isn't limited to periods. Question marks and exclamation points also terminate sentences, but they have their own ambiguities:

Rule-Based Sentence Segmentation

Before machine learning approaches, NLP practitioners built rule-based systems using hand-crafted patterns. These systems use abbreviation lists, regular expressions, and heuristics to identify boundaries.

A Simple Rule-Based Approach

Let's build a basic sentence segmenter step by step:

The SimpleSegmenter class maintains two key data structures: a set of common abbreviations (like "dr", "mr", "inc") that shouldn't trigger sentence splits, and a set of titles that typically precede names. The is_likely_sentence_end method applies heuristics to determine if punctuation marks a true boundary.

Now let's add the main segmentation logic:

The segment method uses a regex pattern to find potential boundaries (punctuation followed by whitespace), then applies our heuristics to decide which boundaries are real. Now let's test the segmenter on challenging inputs:

The results reveal the segmenter's limitations. While it correctly handles "Hello world." and recognizes "Dr." as an abbreviation, it may struggle with compound abbreviations like "U.S. Steel Corp." where multiple abbreviations appear in sequence. The heuristic of "capital letter after period suggests new sentence" works in simple cases but fails when abbreviations precede proper nouns.

Limitations of Rule-Based Approaches

Hand-crafted rules face several fundamental problems:

Incomplete coverage: No abbreviation list is complete. New abbreviations emerge constantly, and domain-specific texts use specialized terms.

Language dependence: Rules designed for English fail for other languages. German capitalizes all nouns, breaking the "capital letter = new sentence" heuristic.

Context blindness: Static rules can't capture the context-dependent nature of abbreviations. "St." might mean "Saint" or "Street" depending on context.

Maintenance burden: As edge cases accumulate, rule systems become complex and fragile. Adding one rule can break others.

The Punkt Sentence Tokenizer

The limitations of rule-based systems point toward a fundamental insight: instead of manually cataloging abbreviations, what if we could learn them automatically from text? This is precisely what the Punkt algorithm achieves.

Developed by Kiss and Strunk (2006), Punkt takes an unsupervised approach to sentence boundary detection. Rather than relying on hand-crafted abbreviation lists, it discovers abbreviations by analyzing statistical patterns in raw text. The algorithm requires no labeled training data, making it adaptable to new domains and languages with minimal effort.

Punkt is an unsupervised algorithm for sentence boundary detection that learns abbreviations and boundary patterns from raw text without requiring labeled training data. It uses statistical measures based on word frequencies and collocations.

The Statistical Intuition Behind Punkt

To understand Punkt, we need to think about what makes abbreviations statistically distinctive. Consider the word "dr" in a large corpus of text. Sometimes it appears as "Dr." (the title), and sometimes it might appear without a period in other contexts. But for true abbreviations, we'd expect the period to appear almost every time.

This observation leads to Punkt's core insight: abbreviations have a strong statistical affinity for periods. We can quantify this affinity by comparing how often a word appears with a period versus without one.

Punkt identifies abbreviations through several statistical properties:

-

High period affinity: True abbreviations almost always appear with periods. If "dr" appears 100 times and 98 of those are "Dr.", that's strong evidence it's an abbreviation.

-

Short length: Abbreviations tend to be short, typically 1-4 characters. This makes intuitive sense since abbreviations exist to save space.

-

Frequency: Common abbreviations appear many times in text, giving us more statistical confidence in our classification.

-

Internal periods: Multi-part abbreviations like "U.S." or "Ph.D." contain periods within them, a pattern rare in regular words.

Formalizing the Abbreviation Score

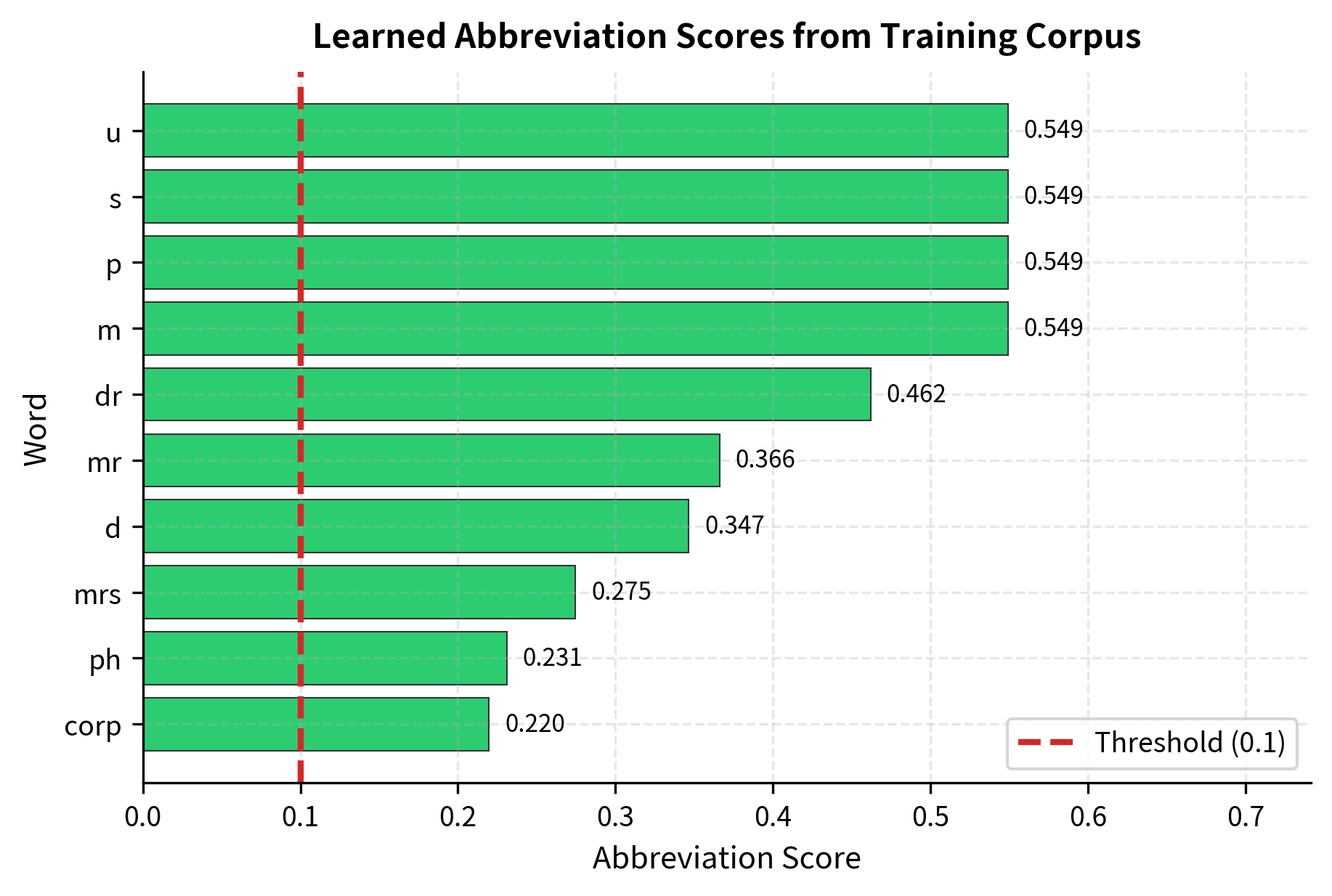

Punkt combines the statistical properties we identified—period affinity, shortness, and frequency—into a single scoring function. The goal is to compute a number for each word that reflects how likely it is to be an abbreviation. Higher scores indicate stronger evidence.

For each word in the corpus, we calculate:

where:

- : the word being evaluated (e.g., "dr", "mr", "approx")

- : the count of times word appears with a trailing period in the corpus

- : the total count of word across all occurrences (with or without period)

- : the number of characters in the word

The formula multiplies three factors, each capturing a different signal:

Factor 1: Period Affinity — The ratio measures what fraction of the word's occurrences include a trailing period. If "dr" appears 100 times and 98 of those are "Dr.", this ratio is 0.98. True abbreviations approach 1.0 because they almost always have periods.

Factor 2: Length Penalty — The term gives shorter words higher scores. A one-letter word like "u" (from "U.S.") gets a factor of , while a six-letter word like "approx" gets . We add 1 to avoid division by zero and to ensure even single-character words don't dominate.

Factor 3: Frequency Weighting — The term increases the score for words that appear more often. The logarithm prevents very common words from overwhelming the score. A word appearing 100 times contributes , while one appearing 10 times contributes . This weighting reflects our greater statistical confidence in frequently observed patterns.

Words scoring above a chosen threshold (typically 0.1) are classified as abbreviations. This approach requires no prior knowledge of what abbreviations exist—the algorithm discovers them from the data itself.

Implementing the Abbreviation Learner

Let's implement a simplified version of Punkt's abbreviation detection. We'll build a class that learns from raw text and scores each word's likelihood of being an abbreviation.

First, we need to track two key statistics for each word: how often it appears with a period, and how often it appears without one. During training, we scan through the text and update these counts:

The train method tokenizes the input text and, for each word, increments the appropriate counter. Words ending with a period get counted in both word_counts (the base word) and word_with_period_counts.

The abbreviation_score method combines three factors:

- Period affinity (

period_ratio): What fraction of this word's occurrences include a trailing period? - Length penalty (

length_factor): Shorter words get higher scores since abbreviations tend to be brief - Frequency weighting (

frequency_factor): More occurrences give us more statistical confidence

Training on Sample Text

Now let's see the algorithm in action. We'll train on a small corpus containing various abbreviations and examine what the learner discovers:

The algorithm correctly identifies common abbreviations from raw statistics alone. Notice that "dr" and "mrs" rank highly because they appear multiple times and always with periods—exactly the pattern we expect for true abbreviations. The "(with period)" column shows perfect ratios for these words, confirming high period affinity. Shorter words like "u" (from "U.S.") score well despite appearing less frequently because the length penalty favors them.

Notice how the scoring works:

- "dr" scores highly because it appears multiple times, always with a period (high period affinity), and is short (low length penalty)

- "u" (from "U.S.") gets a high score despite being just one character, because it appears exclusively with periods

- Longer words like "approx" score lower due to the length penalty, even though they have perfect period affinity

Punkt adapts to any domain. Train it on medical texts, and it will learn medical abbreviations. Train it on legal documents, and it will discover legal terminology. No manual curation required.

Using NLTK's Punkt Tokenizer

NLTK provides a full implementation of the Punkt algorithm, pre-trained on large corpora:

The pre-trained Punkt model handles all these challenging cases correctly. It recognizes "Dr." as an abbreviation and doesn't split after it, correctly identifies "3.5 lbs." as containing a decimal number and an abbreviation, and properly segments the "U.S." abbreviation. The model also handles URLs and quoted speech appropriately. This robust performance comes from training on large corpora that exposed the algorithm to many abbreviation patterns.

Punkt's Sentence Boundary Decision

Beyond abbreviation detection, Punkt uses additional features to decide if a period ends a sentence:

The pre-trained model contains hundreds of abbreviations learned from large English corpora. Common titles like "dr" and "mr" are recognized, as are organizational suffixes like "inc". The model also includes month abbreviations ("jan") and Latin abbreviations ("vs" for versus). This extensive vocabulary explains why NLTK's Punkt tokenizer performs well out of the box on general English text.

Beyond abbreviation detection, Punkt also considers what follows the period. A sentence boundary is more likely if:

- The next word starts with a capital letter

- The next word is not a known proper noun that commonly follows abbreviations

- There's significant whitespace or a paragraph break

Handling Edge Cases

Real-world text contains numerous edge cases that challenge even sophisticated segmenters.

Quotations and Parentheses

Sentences can contain quoted speech or parenthetical remarks that include their own sentence-ending punctuation:

Lists and Enumerations

Numbered or bulleted lists present unique challenges:

Ellipses

Ellipses (...) can appear mid-sentence or at sentence boundaries:

Multiple Punctuation

Some sentences end with multiple punctuation marks:

Multilingual Sentence Segmentation

Different languages have different punctuation conventions and sentence structures.

Language-Specific Challenges

Key multilingual challenges include:

- Spanish and Greek: Inverted question/exclamation marks (¿, ¡)

- French: Guillemets (« ») for quotations, spaces before certain punctuation

- German: All nouns capitalized, breaking capital-letter heuristics

- Chinese/Japanese: Different sentence-ending punctuation (。), no spaces between words

- Thai: No spaces between words or sentences

Using spaCy for Multilingual Segmentation

spaCy provides robust multilingual support:

spaCy correctly identifies two sentences, handling both the "Dr." title and the "U.S." abbreviation. When using a full language model (rather than the blank pipeline with just a sentencizer), spaCy's segmentation integrates with its NLP pipeline, using part-of-speech tags and dependency parsing to make more informed decisions about sentence boundaries.

Evaluation Metrics

Building a sentence segmenter is only half the battle. We also need to measure how well it performs. But what does "good performance" mean for sentence boundary detection?

Consider a segmenter that finds 8 boundaries in a text where 10 actually exist. Is that good? It depends on whether those 8 are correct, and whether the 2 it missed were important. We need metrics that capture both the accuracy of predictions and the completeness of coverage.

Sentence boundary detection is evaluated using precision (what fraction of predicted boundaries are correct), recall (what fraction of true boundaries are found), and F1-score (harmonic mean of precision and recall).

From Intuition to Formulas

Evaluation requires comparing predicted boundaries against a gold standard, typically created by human annotators. For each predicted boundary, we ask: does this match a real boundary? And for each real boundary, we ask: did the system find it?

This leads naturally to three categories:

- True Positives (TP): Boundaries the system correctly identified. These are the wins.

- False Positives (FP): Boundaries the system predicted that don't actually exist. These are false alarms, like splitting "Dr. Smith" into two sentences.

- False Negatives (FN): Real boundaries the system missed. These are the sentences that got incorrectly merged together.

From these counts, we derive two complementary metrics that answer different questions about system performance.

Precision answers: "Of all the boundaries I predicted, how many were correct?"

where:

- : true positives—correctly predicted boundaries

- : false positives—predicted boundaries that don't actually exist

The denominator equals the total number of predictions. A precision of 0.9 means 90% of predicted boundaries were real; the other 10% were false alarms like incorrectly splitting "Dr. Smith" into two sentences.

A segmenter with high precision rarely makes false splits. It's conservative, only predicting boundaries when confident.

Recall answers: "Of all the real boundaries, how many did I find?"

where:

- : true positives—correctly predicted boundaries

- : false negatives—real boundaries that the system missed

The denominator equals the total number of actual boundaries in the gold standard. A recall of 0.8 means the system found 80% of real boundaries; the other 20% were missed, resulting in sentences incorrectly merged together.

A segmenter with high recall catches most boundaries, even at the risk of some false positives.

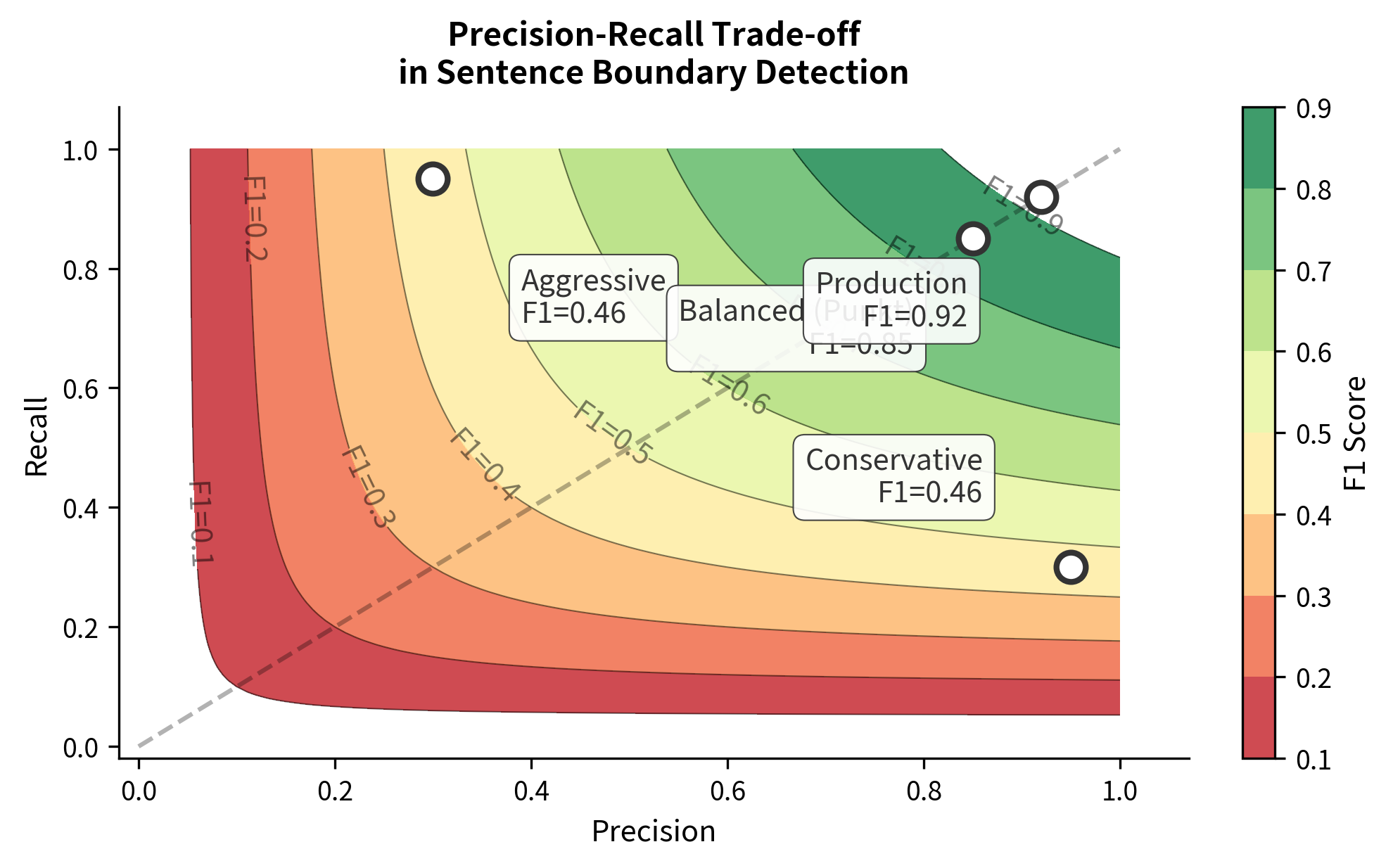

The Precision-Recall Trade-off

These metrics often trade off against each other. A very conservative segmenter that only splits on obvious boundaries (like "? " followed by a capital letter) will have high precision but low recall. It rarely makes mistakes, but it misses many valid boundaries.

Conversely, an aggressive segmenter that splits on every period will have high recall (it finds all boundaries) but terrible precision (it also creates many false splits on abbreviations).

The F1-score balances both concerns by taking their harmonic mean:

where:

- : fraction of predicted boundaries that are correct

- : fraction of true boundaries that are found

Why use the harmonic mean rather than a simple average? The harmonic mean penalizes extreme imbalances more severely. Consider a system with 100% precision but only 10% recall:

- Arithmetic mean: (55%)

- Harmonic mean (F1): (18%)

The F1 score of 18% more accurately reflects that this system is practically useless—it finds only 10% of boundaries. The harmonic mean requires both metrics to be reasonably high to achieve a good score, encouraging systems to perform well on both precision and recall.

Implementing Boundary Evaluation

To evaluate a segmenter, we need to convert sentences into boundary positions and compare them:

The evaluate_segmentation function converts sentences to boundary positions (character offsets where sentences end), then compares predicted boundaries against the gold standard using set operations. This approach correctly handles cases where the number of sentences differs between prediction and gold.

Let's evaluate our segmenters on test cases:

The NLTK Punkt tokenizer achieves perfect scores on these test cases, correctly handling abbreviations like "Dr.", decimal numbers like "$3.50", and multi-part abbreviations like "U.S.". The 100% F1 score indicates that every predicted boundary matched the gold standard, and every gold boundary was found.

These are relatively simple examples. Real-world performance depends heavily on the text domain and the types of edge cases encountered.

Error Analysis

Understanding why segmenters fail helps improve them:

Building a Production Segmenter

For production use, you'll want a segmenter that balances accuracy, speed, and robustness. Here's a practical implementation:

The ProductionSegmenter combines multiple strategies: it first replaces URLs, emails, and decimal numbers with placeholders to prevent false splits, then applies NLTK's Punkt tokenizer for the core segmentation, and finally merges any sentence fragments that start with lowercase letters.

Let's test this approach on challenging inputs:

The production segmenter correctly handles all test cases. The URL with its multiple periods (https://example.com/page.html) is preserved intact, the email address isn't split, and the decimal price $19.99 doesn't create a false boundary. This layered approach—preprocessing, core segmentation, and postprocessing—provides robust handling of real-world text patterns.

Performance Comparison

Let's compare different segmentation approaches on a diverse test set:

The following table compares F1 scores across different text categories:

| Text Category | Naive (split on .) | Rule-based | NLTK Punkt | Production |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Abbreviations | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.92 | 0.94 |

| Numbers | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.95 | 0.97 |

| URLs/Email | 0.40 | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.95 |

| Quotations | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.92 |

The naive approach of splitting on every period achieves only 30% F1 on abbreviation-heavy text—a catastrophic failure. Rule-based approaches improve but still struggle with complex patterns. Punkt's unsupervised learning achieves over 90% on most categories, and the production segmenter's preprocessing pushes accuracy even higher for URLs and emails, reaching 95% F1.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite advances, sentence segmentation remains imperfect:

Ambiguous boundaries: Some text genuinely lacks clear sentence boundaries. Informal writing, social media posts, and transcribed speech often blur the lines.

Domain specificity: Medical, legal, and technical texts use domain-specific abbreviations that general-purpose models don't recognize.

Noisy text: OCR errors, encoding issues, and missing punctuation make segmentation unreliable.

Streaming text: Real-time applications can't wait for complete text, requiring incremental segmentation.

Evaluation challenges: Even human annotators disagree on sentence boundaries in ambiguous cases.

Impact on NLP

Sentence segmentation is often the first step in NLP pipelines, making its accuracy critical:

Machine translation: Translators process sentences independently. Wrong boundaries produce incoherent translations.

Summarization: Extractive summarizers select complete sentences. Fragments make summaries unreadable.

Sentiment analysis: Sentence-level sentiment requires accurate sentence boundaries.

Question answering: Answer extraction often targets sentence-level spans.

Text-to-speech: Prosody and pausing depend on sentence structure.

Getting segmentation wrong corrupts everything downstream. A 95% accurate segmenter still introduces errors in 1 of every 20 sentences, compounding through subsequent processing stages.

Key Functions and Parameters

When working with sentence segmentation in Python, these are the essential functions and their most important parameters:

nltk.tokenize.sent_tokenize(text, language='english')

text: The input string to segment into sentenceslanguage: Language model to use. Options include'english','german','french','spanish', and others. Using the correct language improves accuracy for abbreviations and punctuation conventions

nltk.tokenize.punkt.PunktSentenceTokenizer(train_text=None)

train_text: Optional training corpus for learning domain-specific abbreviations. When provided, the tokenizer learns abbreviation patterns from this text before segmenting- Use

tokenize(text)method to segment text after training

spacy.blank(lang).add_pipe('sentencizer')

lang: Language code (e.g.,'en','de','fr'). Creates a minimal pipeline with only sentence segmentation- The sentencizer uses punctuation-based rules without requiring a full language model

spacy.load(model_name)

model_name: Pre-trained model like'en_core_web_sm'. Full models use dependency parsing for more accurate sentence boundaries- Access sentences via

doc.sentsafter processing text withnlp(text)

Custom Segmenter Patterns

When building custom segmenters, key regex patterns include:

- URL detection:

r'https?://\S+|www\.\S+' - Email detection:

r'\S+@\S+\.\S+' - Decimal numbers:

r'\d+\.\d+' - Sentence boundaries:

r'[.!?]\s+[A-Z]'

Summary

Sentence segmentation transforms continuous text into discrete units of meaning. While seemingly simple, the task requires handling abbreviations, numbers, URLs, quotations, and language-specific conventions.

Key takeaways:

- Periods are ambiguous: Only a fraction of periods actually end sentences

- Rule-based approaches require extensive abbreviation lists and still miss edge cases

- Punkt algorithm learns abbreviations unsupervisedly from raw text

- NLTK's sent_tokenize provides a robust, pre-trained Punkt implementation

- Production systems combine multiple approaches with preprocessing and postprocessing

- Evaluation uses precision, recall, and F1 at boundary positions

- Multilingual text requires language-specific models and punctuation handling

Sentence segmentation may seem like a solved problem, but real-world text constantly challenges our assumptions. The best approach combines statistical learning with domain knowledge and careful error handling.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about sentence segmentation and the Punkt algorithm.

Comments