Learn how to split text into words and tokens using whitespace, punctuation handling, and linguistic rules. Covers NLTK, spaCy, Penn Treebank conventions, and language-specific challenges.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Word Tokenization

Before a computer can understand language, it must break text into meaningful units. Word tokenization is the process of splitting text into individual words or tokens. It sounds trivial: just split on spaces, right? But human language is messy. Contractions like "don't" and "we'll" blur word boundaries. Punctuation clings to words in complex ways. Some languages don't use spaces at all. This chapter explores why tokenization is harder than it looks and how to do it well.

Tokenization is the first step in nearly every NLP pipeline. Get it wrong, and errors cascade through everything downstream. Get it right, and you've built a solid foundation for text analysis, search, translation, and language modeling.

Why Tokenization Matters

Every text processing task begins with tokenization. Consider what happens when you search for a word in a document, count word frequencies, or train a language model. All of these require knowing where one word ends and another begins.

A token is a sequence of characters that forms a meaningful unit for processing. In word tokenization, tokens typically correspond to words, punctuation marks, or other linguistically significant elements.

The definition of "word" varies by application. For some tasks, "New York" should be a single token. For others, "don't" should split into "do" and "n't". There's no universal right answer. The best tokenization depends on what you're trying to accomplish.

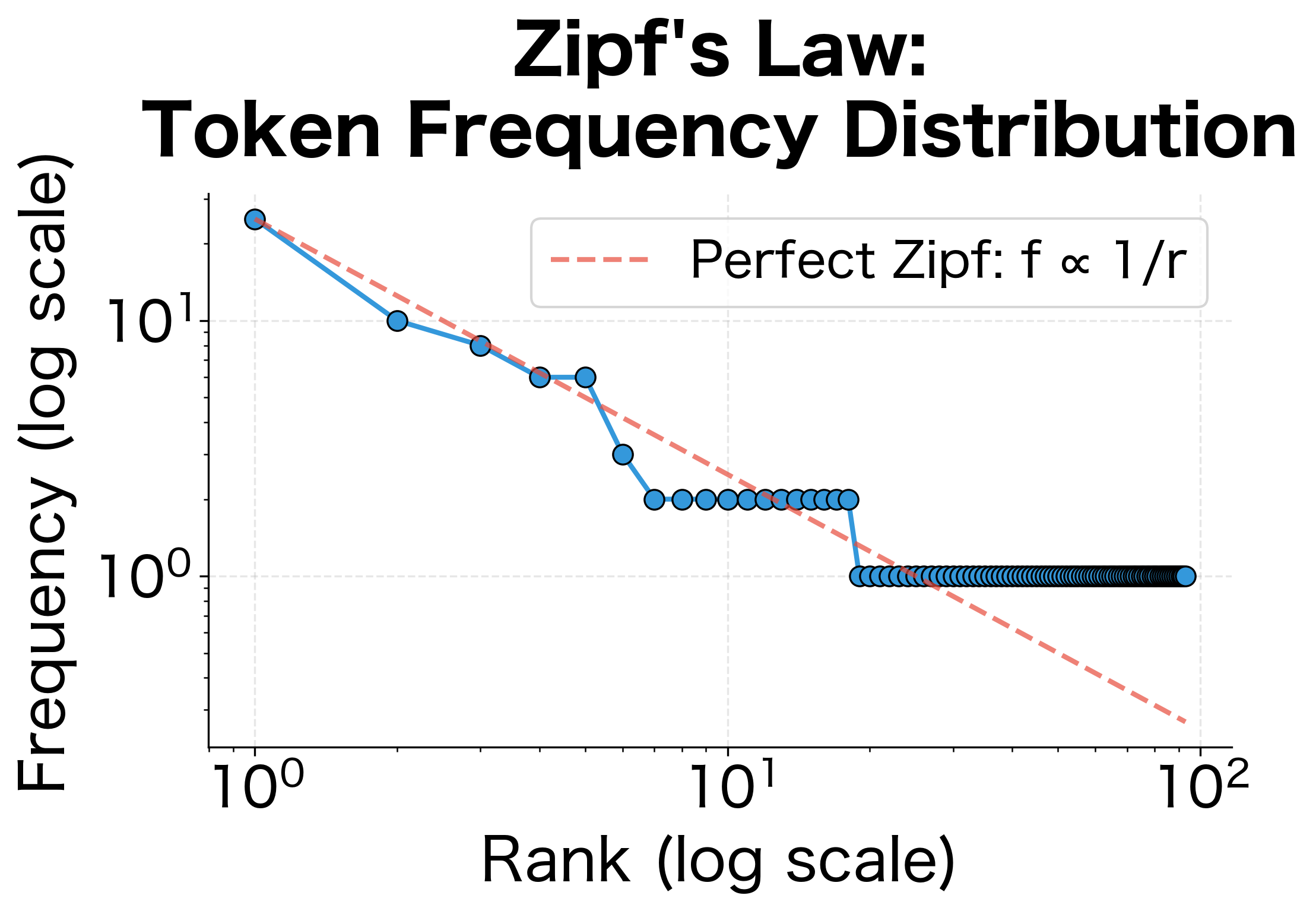

The naive approach produces 7 tokens, lumping punctuation with words. A more sophisticated tokenizer produces 13 tokens, separating punctuation and splitting contractions. Which is correct? It depends on your task. For bag-of-words models, you might want "don't" as one token. For syntactic parsing, splitting into "do" and "n't" reveals the underlying structure.

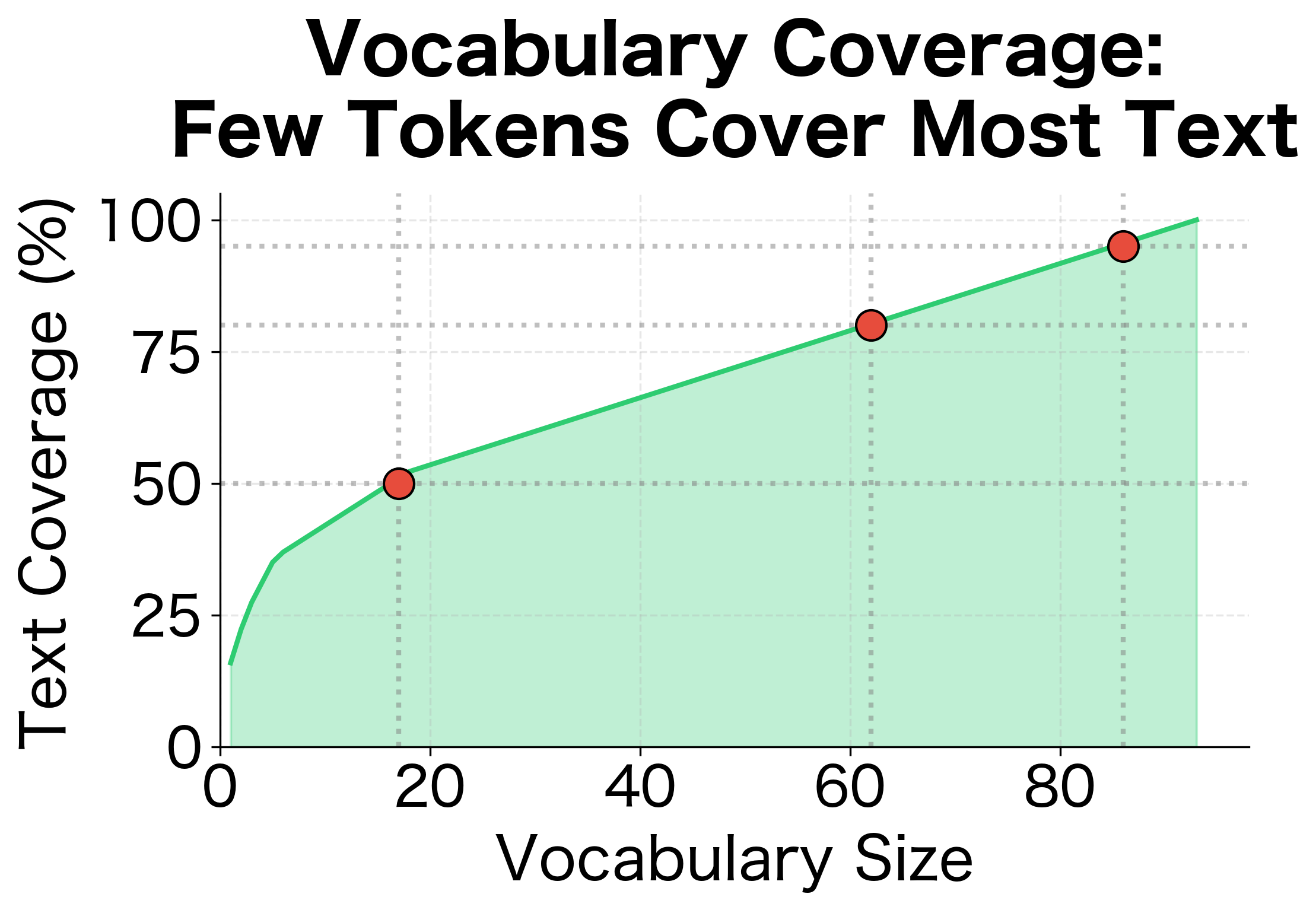

Tokenization also determines your vocabulary. A larger corpus with naive tokenization might produce tokens like "waiting.", "waiting,", and "waiting" as three separate vocabulary entries. Better tokenization consolidates these into a single "waiting" entry plus punctuation tokens, improving vocabulary efficiency.

Whitespace Tokenization

The simplest tokenization strategy splits text on whitespace characters: spaces, tabs, and newlines. This works surprisingly well for many English texts.

Python's split() method handles multiple consecutive whitespace characters gracefully, collapsing them into a single delimiter. But notice the problem: punctuation stays attached to words. "Hello," and "world!" are not the tokens we want for most applications.

Limitations of Whitespace Tokenization

Whitespace tokenization fails in predictable ways:

- Punctuation attachment: Commas, periods, and other punctuation stick to adjacent words. "Hello," becomes a different token from "Hello".

- Contractions: "don't" stays as one token, hiding its two-word structure.

- Hyphenated compounds: "state-of-the-art" becomes one token, though it might be better as four.

- Numbers and dates: "3.14" and "2024-01-15" contain delimiters that shouldn't split.

- URLs and emails: "user@example.com" and "https://example.com" contain no spaces but have internal structure.

Each example shows a different failure mode. The contraction "can't" stays fused. The hyphenated compound becomes one long token. The email address is treated as a single word. These aren't bugs in the tokenizer. They're fundamental limitations of using whitespace as the only delimiter.

Punctuation Handling

Most tokenizers treat punctuation as separate tokens. This makes sense linguistically: a period ends a sentence, a comma separates clauses, and quotation marks delimit speech. These are meaningful units that deserve their own tokens.

Now punctuation is separated. But we've introduced new problems. What about abbreviations like "Dr." or "U.S.A."? What about decimal numbers like "3.14"? What about contractions?

Handling Abbreviations

Abbreviations pose a challenge: the period is part of the word, not a sentence-ending punctuation mark. A robust tokenizer needs to know which periods to separate and which to keep.

The abbreviation-aware tokenizer keeps "Dr.", "Mr.", "p.m.", and "U.S." intact while still separating the final period. This pattern of protecting special cases before applying general rules is common in NLP.

Contractions and Clitics

Contractions present a linguistic puzzle. "Don't" is one orthographic word but represents two morphemes: "do" and "not". How should we tokenize it?

A clitic is a morpheme that has syntactic characteristics of a word but is phonologically dependent on an adjacent word. English contractions like "'s", "'ll", and "n't" are clitics that attach to their host words.

Different traditions handle contractions differently:

- Keep together: "don't" ["don't"]

- Split at apostrophe: "don't" ["don", "'t"]

- Expand fully: "don't" ["do", "n't"]

- Normalize: "don't" ["do", "not"]

Splitting contractions reveals the underlying structure. "Can't" becomes "can" and "n't", exposing the negation. "She's" becomes "she" and "'s", which could be either possessive or "is" depending on context. Note that this simple approach differs from Penn Treebank conventions, which split "can't" into "ca" and "n't" to better reflect the morphological structure.

The Possessive Problem

The possessive "'s" is particularly tricky. In "John's book", the "'s" marks possession. In "John's running", it's a contraction of "is". Both look identical, and only context reveals the difference.

A tokenizer can't distinguish these cases without understanding grammar. This is a fundamental limitation: tokenization is a preprocessing step that happens before syntactic analysis. We split "'s" consistently and leave disambiguation to later stages.

Penn Treebank Tokenization

The Penn Treebank tokenization standard emerged from the Penn Treebank project, a large annotated corpus of English text. It established conventions that many NLP tools follow:

- Split contractions: "don't" "do n't"

- Separate punctuation: "Hello," "Hello ,"

- Keep abbreviations: "Dr." stays as "Dr."

- Handle special cases: "$" and "%" attach to numbers

The Treebank tokenizer handles contractions, punctuation, and special cases according to established conventions. Notice how it splits "can't" into "ca" and "n't", keeps "Dr." together, and handles the dollar amount and percentage.

Treebank Conventions

The Penn Treebank standard makes specific choices:

| Input | Output | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| don't | do n't | Reveals negation structure |

| I'm | I 'm | Separates subject from verb |

| they're | they 're | Consistent clitic handling |

| John's | John 's | Possessive/contraction split |

| "Hello" | `` Hello '' | Directional quotes |

| (test) | -LRB- test -RRB- | Bracket normalization |

The Treebank tokenizer converts ASCII quotes to directional quote tokens (`` and '') and brackets to labeled tokens (-LRB- and -RRB-). These conventions normalize text for consistent downstream processing.

Language-Specific Challenges

English, with its space-separated words, is relatively easy to tokenize. Other languages present unique challenges.

Chinese: No Word Boundaries

Chinese text contains no spaces between words. Characters flow continuously, and determining word boundaries requires linguistic knowledge.

Character tokenization produces 11 tokens, one per character. Word tokenization produces fewer, more meaningful units. The word tokenizer identifies "自然语言处理" (natural language processing) as a compound word, while character tokenization would split it into individual characters.

The impact of tokenization granularity varies dramatically across languages:

| Language | Example Text | Character Tokens | Word Tokens | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | "Hello world" | 11 | 2 | 5.5× |

| Chinese | "我喜欢学习自然语言处理" | 11 | 5 | 2.2× |

| Japanese | "私はPythonでNLPを勉強しています" | 20 | 11 | 1.8× |

Languages without explicit word boundaries (Chinese, Japanese) show smaller differences between character and word tokenization because word boundaries must be inferred. English shows the largest ratio because whitespace already provides clear word boundaries, making character tokenization produce many more tokens than word tokenization.

Japanese: Mixed Scripts

Japanese uses three writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji (Chinese characters). Words can be written in any combination, and spaces are rarely used.

Japanese tokenization must handle the mixing of scripts. "Python" and "NLP" are written in Latin characters, while the rest uses Japanese scripts. A good tokenizer recognizes these boundaries and segments appropriately.

German: Compound Words

German creates long compound words by concatenating shorter words without spaces. "Donaudampfschifffahrtsgesellschaftskapitän" (Danube steamship company captain) is a single orthographic word.

For some applications, you might want to decompose compounds into their constituent parts. This requires morphological analysis beyond simple tokenization.

Arabic: Complex Morphology

Arabic presents multiple challenges: right-to-left script, complex morphology with prefixes and suffixes attached to words, and optional vowel diacritics.

Arabic whitespace tokenization works at the surface level, but a single orthographic word often contains multiple morphemes that might be separate tokens in other languages.

Building a Rule-Based Tokenizer

Let's build a more complete tokenizer that handles common English patterns. We'll combine the techniques we've discussed into a coherent system.

Now let's test our tokenizer on various challenging inputs:

Our tokenizer handles abbreviations, contractions, and punctuation correctly. It's not perfect, but it demonstrates the rule-based approach.

Limitations of Rule-Based Tokenization

Rule-based tokenizers have inherent limitations:

- Coverage: You can't anticipate every abbreviation or special case. New abbreviations emerge constantly.

- Ambiguity: "St." could be "Street" or "Saint". "Dr." could be "Doctor" or "Drive". Rules can't disambiguate without context.

- Language dependence: Rules written for English don't work for other languages. Each language needs its own rule set.

- Maintenance burden: As edge cases accumulate, rule sets become complex and brittle.

The tokenizer handles some cases well but struggles with URLs, emails, and unlisted abbreviations. Production tokenizers address these with more comprehensive rules or statistical methods.

Using NLTK and spaCy

Production NLP work typically uses established libraries rather than custom tokenizers. NLTK and spaCy are the two most popular choices for English.

NLTK Tokenizers

NLTK provides several tokenization options:

Each tokenizer makes different choices. word_tokenize uses the Punkt sentence tokenizer combined with a word tokenizer. wordpunct_tokenize splits on both whitespace and punctuation. TreebankWordTokenizer follows Penn Treebank conventions.

spaCy Tokenizer

spaCy's tokenizer is rule-based but highly optimized and configurable:

spaCy provides not just tokens but also part-of-speech tags, punctuation flags, and stop word indicators. This additional information is useful for downstream processing.

Comparing Tokenizers

Let's compare how different tokenizers handle the same challenging text:

Different tokenizers make different choices about contractions, punctuation, and social media elements like hashtags and mentions. There's no universally "correct" answer. The best choice depends on your application.

The following table summarizes how each tokenizer performs on the challenge text:

| Tokenizer | Token Count | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Whitespace | 9 | Keeps punctuation attached, fewest tokens |

| NLTK word_tokenize | 17 | Splits contractions, separates punctuation |

| NLTK Treebank | 17 | Penn Treebank conventions, normalizes quotes |

| spaCy | 17 | Rich token attributes (POS, flags) |

| Our tokenizer | 17 | Custom rules, configurable behavior |

The variation in token counts (from 9 to 17 for the same input) highlights that tokenization is not a solved problem with a single correct answer. Whitespace tokenization produces the fewest tokens by keeping punctuation attached, while linguistic tokenizers like NLTK and spaCy produce nearly twice as many tokens by separating punctuation and splitting contractions.

Tokenization Evaluation

How do you know if your tokenizer is working correctly? Unlike many NLP tasks where quality is subjective, tokenization can be evaluated objectively: either a token boundary is in the right place, or it isn't. But this requires something to compare against: a gold standard of human-annotated text with correct token boundaries.

The core insight is that tokenization is fundamentally a boundary detection problem. We're not just counting tokens; we're asking: did the tokenizer place boundaries in the correct positions? This framing leads naturally to the standard evaluation metrics.

The Boundary Detection Framework

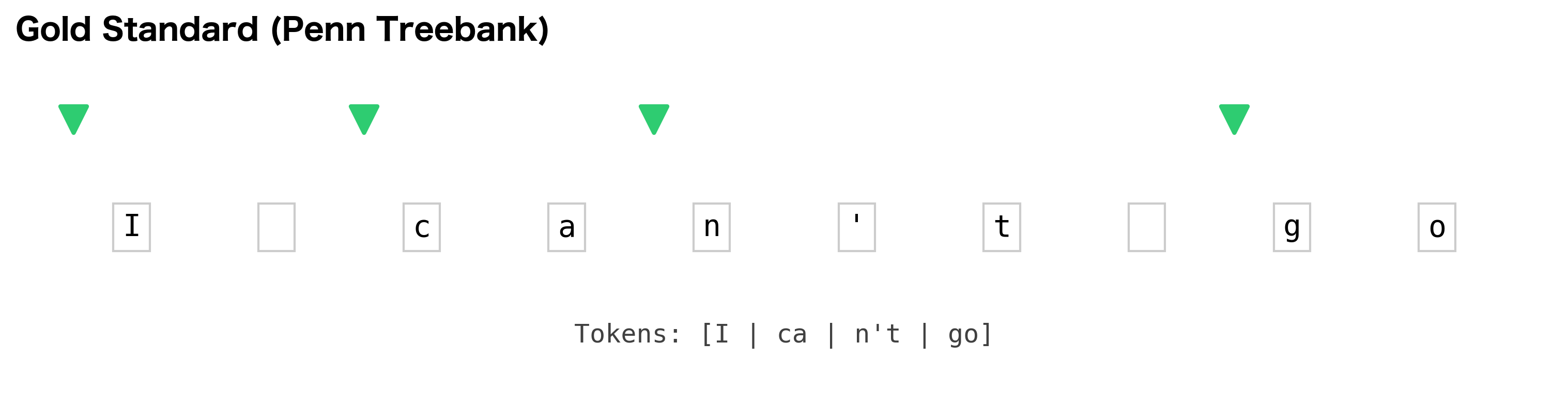

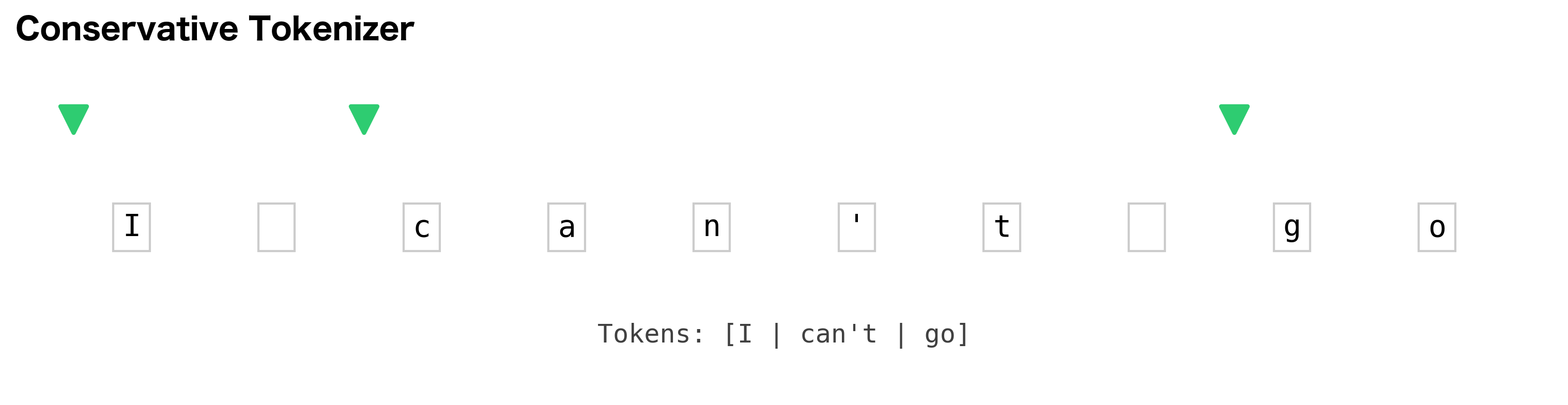

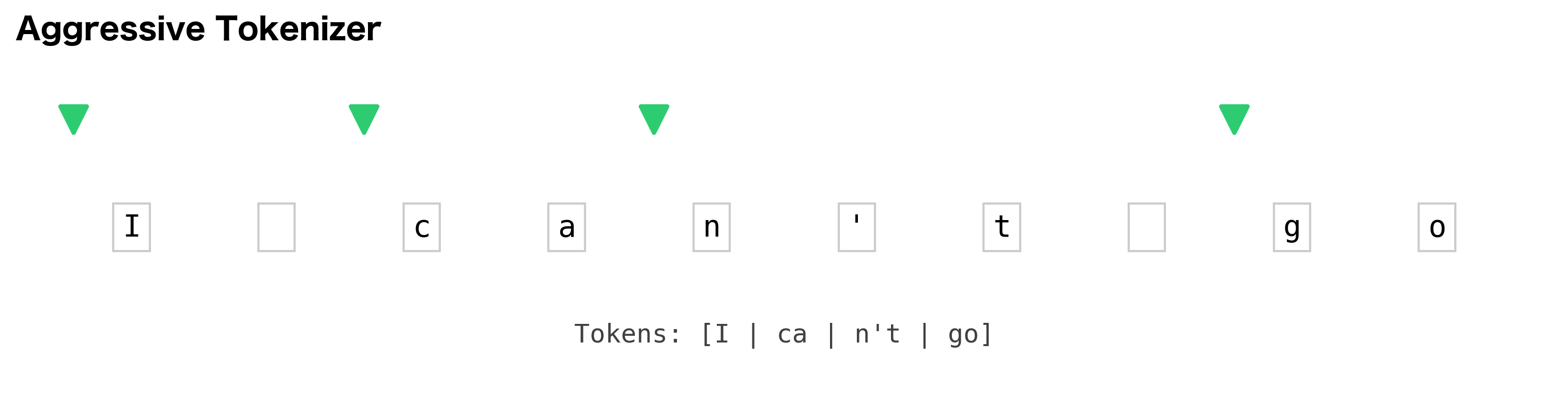

Think of a text as a sequence of character positions. A tokenizer's job is to decide which positions mark the start of a new token. Consider the sentence "I can't go":

Position: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Text: I c a n ' t g o

A tokenizer that keeps contractions together places boundaries at positions 0, 2, and 8, producing ["I", "can't", "go"]. A tokenizer that splits contractions places boundaries at positions 0, 2, 4, and 8, producing ["I", "ca", "n't", "go"]. The evaluation question becomes: which boundaries match the gold standard?

Evaluation Metrics

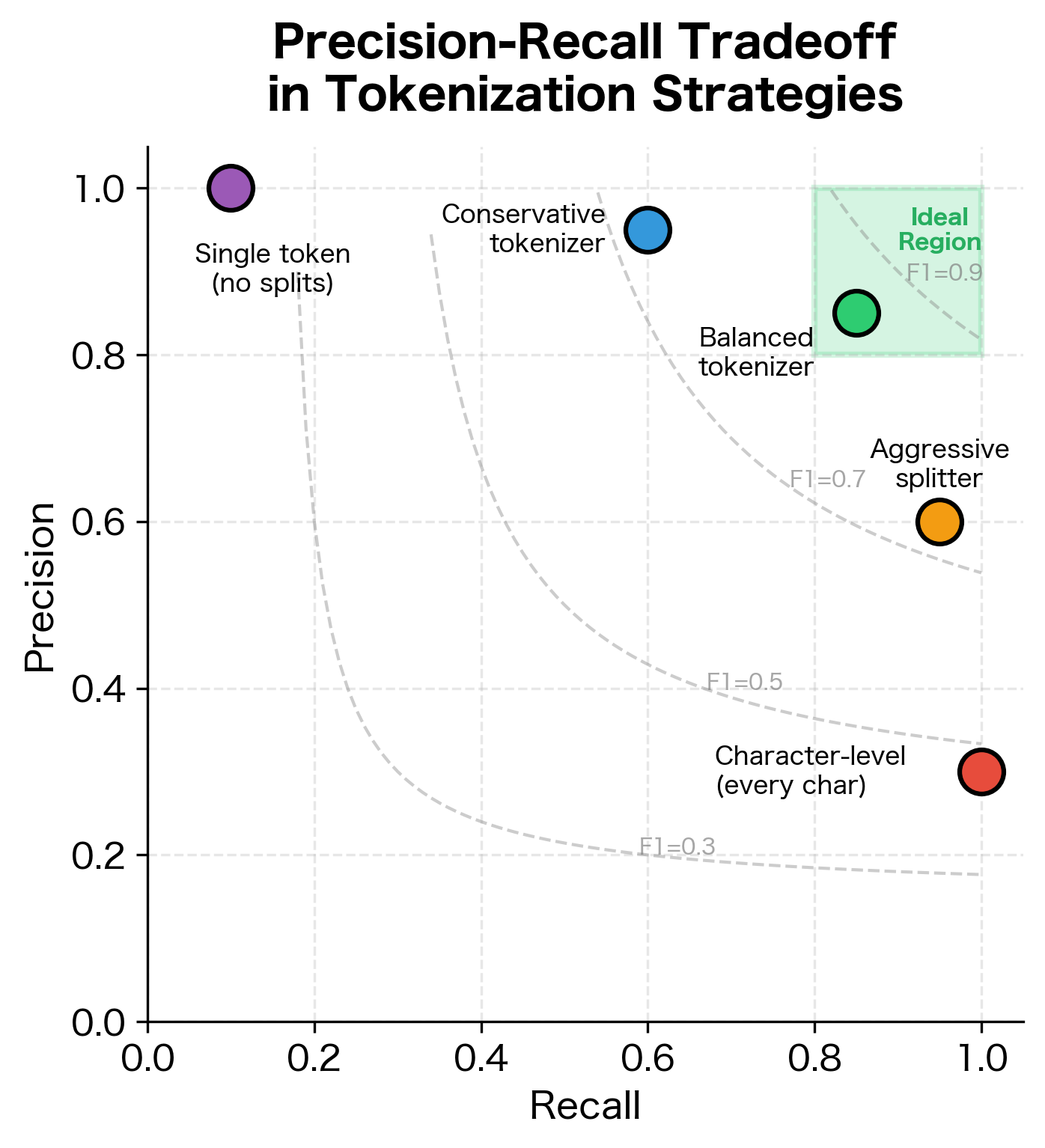

With this boundary-based view, we can apply the classic precision-recall framework from information retrieval.

Precision answers: of all the boundaries the tokenizer predicted, how many were actually correct? A tokenizer with high precision makes few false boundary predictions. It might miss some boundaries (under-tokenizing), but when it does place a boundary, it's usually right.

where:

- : the set of boundary positions predicted by the tokenizer

- : the set of true boundary positions in the gold standard

- : the number of correctly predicted boundaries (the intersection of predicted and gold boundaries)

- : the total number of boundaries the tokenizer predicted

Recall answers the complementary question: of all the true boundaries in the gold standard, how many did the tokenizer find? A tokenizer with high recall catches most boundaries. It might predict some spurious boundaries (over-tokenizing), but it rarely misses a real one.

where:

- : the number of correctly predicted boundaries (same as in precision)

- : the total number of true boundaries in the gold standard

Neither metric alone tells the full story. A tokenizer that places a boundary after every character would have perfect recall but terrible precision. A tokenizer that outputs the entire text as one token would have perfect precision on its single boundary but miss all the others.

F1 Score balances both concerns by computing the harmonic mean of precision and recall. The harmonic mean penalizes extreme imbalances: if either precision or recall is low, F1 will be low, even if the other is high.

where:

- : the fraction of predicted boundaries that are correct (as defined above)

- : the fraction of true boundaries that were found (as defined above)

- The factor of 2 ensures that when precision equals recall, equals both values

Let's implement this evaluation framework and see it in action:

The get_boundaries function walks through the token list, tracking character positions. Each token's starting position becomes a boundary. We then compute the set intersection between predicted and gold boundaries to count correct predictions.

The predicted tokenization scores below 100% because it didn't split the contractions "can't" and "it's". The gold standard expects boundaries at "ca|n't" and "it|'s", but our tokenizer kept these as single tokens. This illustrates an important point: whether this is an "error" depends entirely on the task. For syntactic parsing, the gold standard is correct. For bag-of-words text classification, keeping contractions together might actually be preferable.

Common Evaluation Corpora

Standard tokenization benchmarks include:

- Penn Treebank: The original standard for English tokenization

- Universal Dependencies: Cross-lingual treebanks with consistent tokenization

- CoNLL shared tasks: Various NLP benchmarks with tokenization components

Subword Tokenization Preview

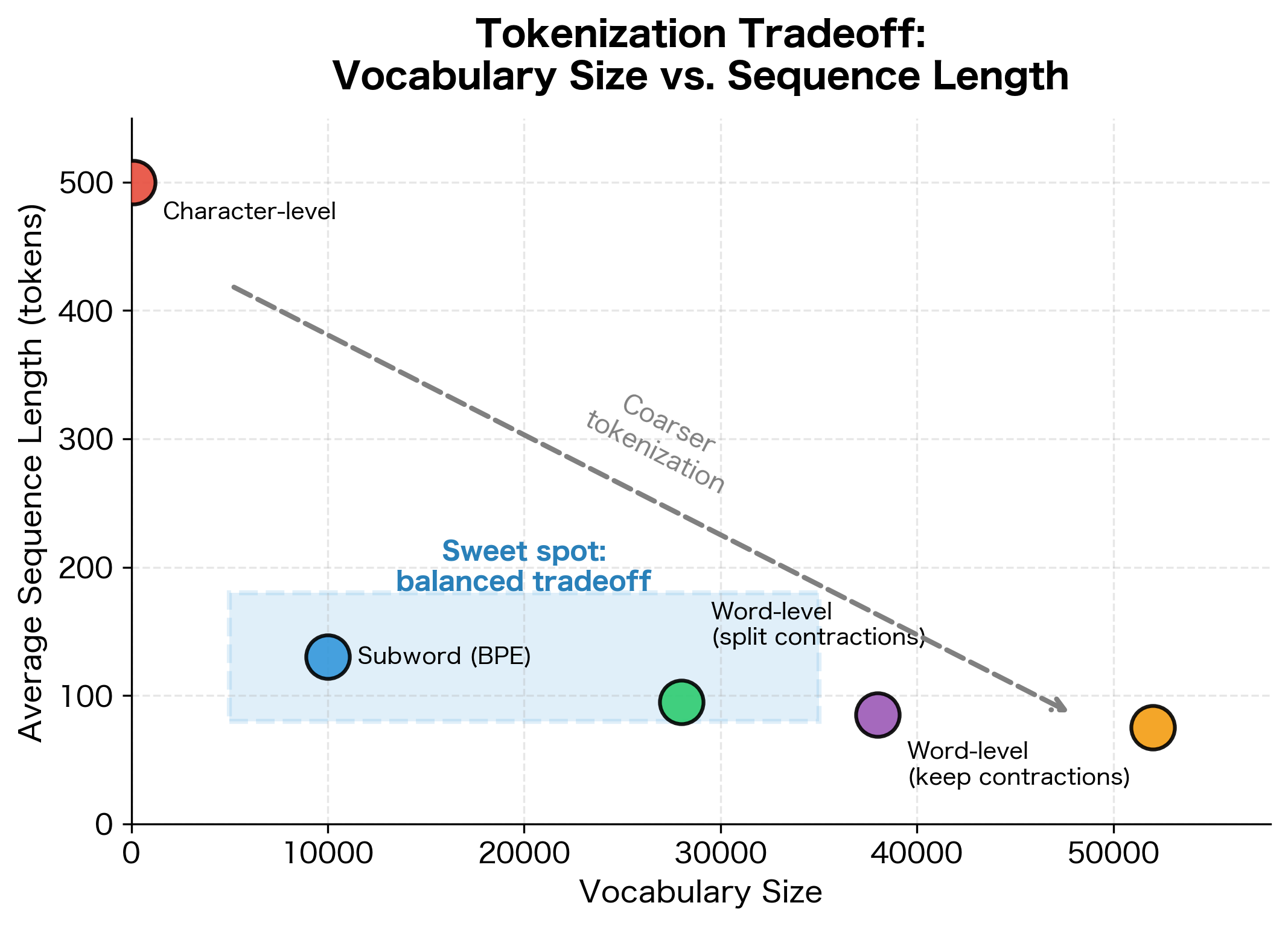

Modern neural NLP systems often use subword tokenization instead of word tokenization. Methods like Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), WordPiece, and SentencePiece break words into smaller units.

Subword tokenization offers advantages: smaller vocabularies, better handling of rare words, and no out-of-vocabulary problem. We'll explore these methods in detail in a later chapter.

The following table illustrates the granularity spectrum for the word "unhappiness":

| Granularity | Tokens | Token Count | Vocab Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word | ["unhappiness"] | 1 | Large vocabulary needed |

| Morpheme | ["un", "happi", "ness"] | 3 | Meaningful subunits |

| BPE-style | ["un", "happ", "iness"] | 3 | Data-driven splits |

| Character | ["u","n","h","a","p","p","i","n","e","s","s"] | 11 | Fixed small vocabulary |

Finer granularities (character-level) produce more tokens but require smaller vocabularies since every word can be built from a small set of characters. Coarser granularities (word-level) produce fewer tokens but require larger vocabularies to cover all possible words. Subword methods like BPE and WordPiece occupy a middle ground, balancing vocabulary size with sequence length.

Limitations and Challenges

Word tokenization, despite decades of research, remains imperfect:

- No universal definition of "word": Linguistic theories disagree on what constitutes a word. Tokenizers make practical choices that may not align with any particular theory.

- Language diversity: Rules that work for English fail for Chinese, Arabic, or German. Each language family requires specialized approaches.

- Domain variation: Medical text, legal documents, social media, and code each have unique tokenization challenges. A tokenizer trained on news articles may struggle with tweets.

- Evolving language: New words, abbreviations, and conventions emerge constantly. "COVID-19", "blockchain", and "emoji" didn't exist decades ago.

- Ambiguity: Many tokenization decisions are genuinely ambiguous. Should "New York" be one token or two? Should "ice-cream" be split?

Impact on Downstream Tasks

Tokenization choices ripple through the entire NLP pipeline:

- Vocabulary size: Splitting contractions increases vocabulary slightly but improves coverage. Keeping compounds together reduces vocabulary but may hurt generalization.

- Sequence length: More tokens mean longer sequences. This affects model training time and memory usage.

- Semantic alignment: Tokens should ideally correspond to meaningful units. Poor tokenization can obscure semantic relationships.

- Cross-lingual transfer: Inconsistent tokenization across languages makes multilingual models harder to train.

Summary

Word tokenization breaks text into meaningful units for processing. While conceptually simple, the task is surprisingly complex due to punctuation, contractions, abbreviations, and language-specific challenges.

Key takeaways:

- Whitespace tokenization is fast but leaves punctuation attached to words

- Punctuation separation improves token quality but requires handling abbreviations

- Contractions can be kept together, split at the apostrophe, or expanded

- Penn Treebank conventions provide a standard for English tokenization

- Languages without spaces (Chinese, Japanese) require specialized segmenters

- Compound words (German) may need morphological decomposition

- Rule-based tokenizers are interpretable but require extensive rule sets

- Library tokenizers (NLTK, spaCy) handle common cases well

- Evaluation uses precision, recall, and F1 against gold standards

- Tokenization choices affect all downstream NLP tasks

The right tokenization strategy depends on your task, language, and domain. There's no universal best approach. Understanding the tradeoffs helps you make informed decisions for your specific application.

Key Functions and Parameters

When working with tokenization in Python, these are the essential functions and their most important parameters:

str.split(sep=None)

sep: The delimiter string. WhenNone(default), splits on any whitespace and removes empty strings from the result. Useful for basic whitespace tokenization.

nltk.tokenize.word_tokenize(text, language='english')

text: The input string to tokenizelanguage: Language for the Punkt tokenizer. Affects sentence boundary detection and abbreviation handling. Supports 17 languages including English, German, French, and Spanish.

nltk.tokenize.TreebankWordTokenizer().tokenize(text)

text: The input string to tokenize. Returns tokens following Penn Treebank conventions: splits contractions, separates punctuation, and normalizes quotes and brackets.

spacy.load(name)

name: Model name (e.g.,'en_core_web_sm','en_core_web_lg'). Larger models provide better accuracy but require more memory. The tokenizer is included in all models.

nlp(text) (spaCy Doc object)

- Returns a

Docobject where eachTokenhas attributes:text(string),pos_(part-of-speech),is_punct(punctuation flag),is_stop(stop word flag),lemma_(base form).

jieba.cut(text, cut_all=False)

text: Chinese text to segmentcut_all: WhenTrue, uses full mode (all possible segmentations). WhenFalse(default), uses accurate mode (most likely segmentation). Accurate mode is preferred for most NLP tasks.

re.sub(pattern, replacement, text)

pattern: Regular expression to matchreplacement: String or function to replace matches. User' \1 'to surround captured groups with spaces, useful for separating punctuation.text: Input string. Essential for building custom tokenizers with punctuation handling.

In the next chapter, we'll explore subword tokenization methods that break words into smaller units, addressing vocabulary limitations and rare word handling.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about word tokenization.

Comments