Master smoothing techniques that solve the zero probability problem in n-gram models, including Laplace, add-k, Good-Turing, interpolation, and Kneser-Ney smoothing with Python implementations.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Smoothing Techniques

N-gram language models have a fatal flaw: they assign zero probability to any sequence containing an n-gram not seen during training. A single unseen word combination causes the entire sentence probability to collapse to zero, making the model useless for real-world text. Smoothing techniques solve this problem by redistributing probability mass from observed n-grams to unseen ones, ensuring every possible sequence receives some non-zero probability.

This chapter explores the evolution of smoothing methods, from simple add-one smoothing to the sophisticated Kneser-Ney algorithm that powered speech recognition and machine translation systems for decades.

The Zero Probability Problem

Consider a bigram model trained on a small corpus. You calculate probabilities by counting how often word pairs appear:

where:

- : probability of word given the preceding word

- : count of the bigram (how often the word pair appears together)

- : count of the preceding word (how often it appears as context)

The problem emerges immediately. If your training corpus contains "the cat sat on the mat" but never "the cat ate the fish," then . When computing the probability of a new sentence using the chain rule, a single zero multiplies everything to zero:

This is catastrophic. The sentence is perfectly grammatical, yet our model claims it's impossible.

The process of adjusting probability estimates to reserve some probability mass for unseen events. Smoothing ensures that no valid sequence receives zero probability, making the model robust to novel inputs.

Add-One (Laplace) Smoothing

The simplest solution is to pretend every n-gram occurred at least once. Add one to all counts before computing probabilities:

where:

- : the Laplace-smoothed probability of word given the preceding word

- : count of the bigram (how often the word pair appears together)

- : count of the context word (how often appears)

- : vocabulary size (total number of unique words)

We add 1 to the numerator to give the specific bigram a "pseudocount." We add to the denominator because we're adding 1 to each of the possible words that could follow . This ensures the probability distribution still sums to 1.

Let's trace through the math. Suppose "the cat" appears 5 times in our corpus, "the" appears 100 times, and our vocabulary has 10,000 words.

Without smoothing:

With Laplace smoothing:

The probability dropped by nearly two orders of magnitude. This is the fundamental problem with Laplace smoothing: it steals too much probability mass from observed events to give to unseen ones.

Worked Example: Laplace Smoothing

Consider a tiny corpus with vocabulary and these bigram counts:

| Bigram | Count |

|---|---|

| (a, b) | 3 |

| (a, c) | 1 |

| (b, a) | 2 |

| (b, c) | 0 |

| (c, a) | 1 |

| (c, b) | 0 |

The unigram counts are: , , .

For MLE probabilities:

For Laplace-smoothed probabilities (with ):

And for the unseen bigram (a, a):

Notice how the probabilities for observed bigrams decreased significantly to make room for the unseen one.

Add-k Smoothing

A natural improvement is to add a smaller constant instead of 1:

where:

- : the smoothed probability of word given the preceding word

- : count of the bigram (how often the word pair appears together)

- : count of the context word (how often appears)

- : the smoothing constant, a value between 0 and 1 (typically 0.001 to 0.5)

- : vocabulary size (total number of unique words)

The key insight is that we add to the numerator for the specific bigram, but we add to the denominator because we're adding to each of the possible words that could follow . This preserves the probability distribution property that all conditional probabilities given sum to 1.

With and our earlier example:

This is still far from the original 0.05, but it's less aggressive than Laplace smoothing.

Tuning k

The optimal value of depends on your corpus and vocabulary size. You can tune it by:

- Holding out a development set

- Computing perplexity for different values of

- Selecting the that minimizes perplexity

Typical values range from 0.001 to 0.5. Smaller corpora often need larger values, while larger corpora can use smaller ones.

First, let's examine the basic statistics of our corpus:

Our small corpus yields a vocabulary of 12 unique tokens and 30 bigram instances. The most frequent bigram is ("the", "cat") appearing twice, which makes sense given our cat-and-dog themed sentences. This manageable size lets us trace through the smoothing calculations by hand if needed.

Let's implement add-k smoothing and see how different values of affect probability estimates:

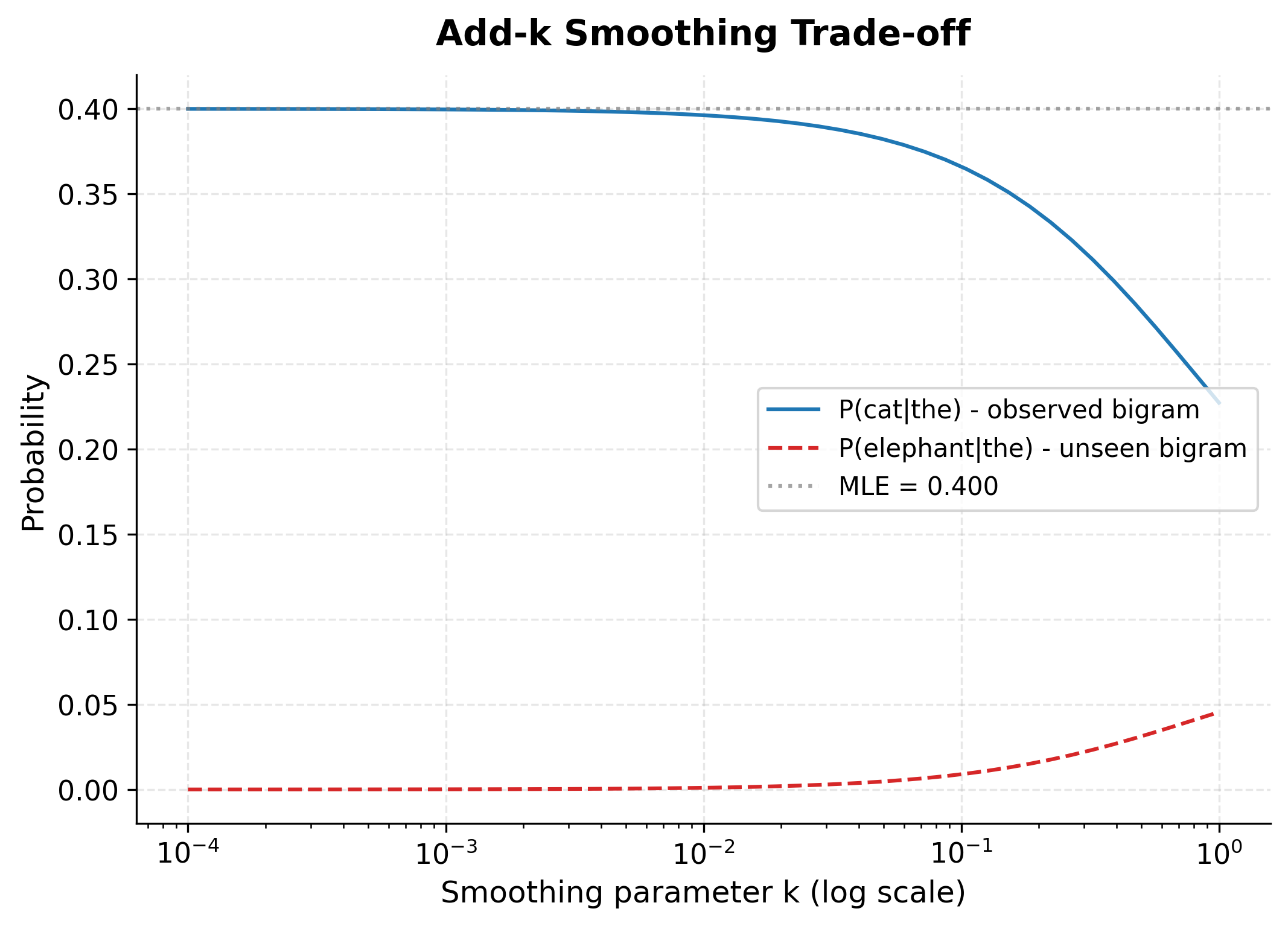

We'll compare probabilities for an observed bigram ("the", "cat") and an unseen bigram ("the", "elephant"):

The MLE probability for P(cat|the) would be 2/10 = 0.2. With k=1.0 (Laplace), this drops to about 0.136, losing nearly a third of the probability mass. As k decreases to 0.001, the probability climbs back to 0.196, much closer to the MLE.

For the unseen bigram "the elephant," we see the flip side: larger k values give it more probability (0.045 with k=1.0), while smaller values give it less (0.0001 with k=0.001). This is the core trade-off in smoothing: how much probability to steal from observed events to cover unseen ones.

The plot reveals the fundamental trade-off. As increases, the blue curve (observed bigram) falls while the red curve (unseen bigram) rises. The gray dotted line shows the MLE estimate we're trying to preserve for observed events. Choosing means finding the right balance: small enough to keep observed probabilities reasonable, large enough to give unseen events meaningful coverage.

Good-Turing Smoothing

Add-k smoothing has an arbitrary feel to it. Why add 0.1 rather than 0.05 or 0.2? Good-Turing smoothing takes a fundamentally different approach: instead of picking a constant, it uses the statistical structure of the data itself to determine how much probability mass should go to unseen events.

The Key Insight: Learning from Singletons

The core idea is elegant. If we collected more data, some n-grams that currently appear zero times would appear once. Some that appear once would appear twice. Good-Turing asks: can we use the current distribution of counts to predict this future behavior?

The answer is yes. Consider n-grams that appear exactly once in our corpus (called singletons or hapax legomena). These are the n-grams that barely made it into our observations. If we had slightly less data, many of them would have count zero. Conversely, if we had slightly more data, many currently unseen n-grams would become singletons.

This suggests that the number of singletons tells us something about unseen n-grams. More precisely: the probability mass that should go to unseen events is proportional to the number of singletons.

The count represents how many distinct n-grams appear exactly times in the corpus. For example, is the number of n-grams that appear exactly once (hapax legomena), and is the number of n-grams that never appear.

The Good-Turing Formula

Good-Turing formalizes this intuition by replacing the observed count with an adjusted count :

where:

- : the original observed count for an n-gram

- : the adjusted (discounted) count that replaces

- : the number of distinct n-grams that appear exactly times in the corpus

- : the number of distinct n-grams that appear exactly times

The formula works by looking one step ahead in the count distribution. The ratio tells us how the frequency of frequencies changes as counts increase. If there are relatively few n-grams with count compared to those with count , the ratio is small, which means count is probably an overestimate that should be discounted heavily.

For unseen n-grams (count 0), the adjusted count becomes:

where:

- : the number of singletons (n-grams appearing exactly once)

- : the number of possible n-grams that were never observed

This formula estimates how much "count" each unseen n-gram deserves by distributing the singleton count across all unseen events.

The total probability mass reserved for all unseen events is:

where:

- : the total probability mass allocated to all unseen n-grams combined

- : the number of singletons

- : the total number of n-gram tokens in the corpus

This elegant result says: the fraction of probability mass for unseen events equals the fraction of tokens that are singletons. If 10% of your corpus consists of words that appear only once, then roughly 10% of probability mass should go to unseen events.

Worked Example: Good-Turing

Suppose we have a corpus with these frequency counts:

| Count | (n-grams with this count) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 74,671,100,000 |

| 1 | 2,018,046 |

| 2 | 449,721 |

| 3 | 188,933 |

| 4 | 105,668 |

| 5 | 68,379 |

For bigrams that appear exactly once:

This means a bigram seen once should be treated as if it appeared only 0.446 times. The "missing" 0.554 goes to unseen bigrams.

For unseen bigrams:

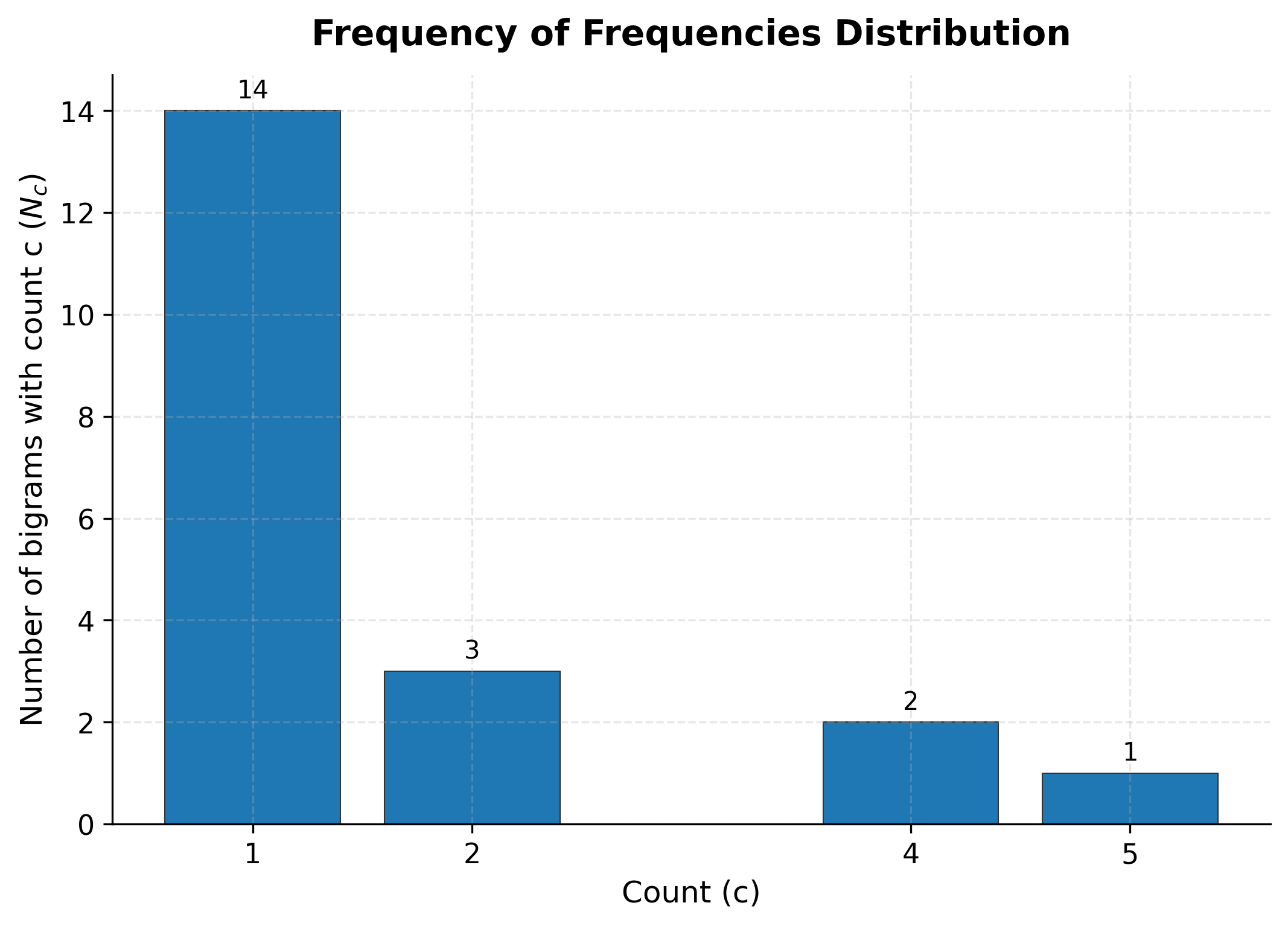

Now we can examine the frequency of frequencies distribution and compute adjusted counts:

Our corpus shows a typical pattern: many bigrams appear only once (singletons), fewer appear twice, and so on. The adjusted count for singletons (c=1) drops significantly because Good-Turing uses the ratio of doubletons to singletons. When this ratio is less than 0.5, singletons get discounted heavily.

The distribution follows the expected pattern: most bigrams are rare (appearing only once or twice), while a few appear frequently. This Zipfian distribution is why Good-Turing works: the steep decline from to to provides the ratios needed to estimate appropriate discounts.

Good-Turing works well for small counts but becomes unreliable for larger counts where values become sparse or zero. In practice, it's often combined with other techniques.

Backoff and Interpolation

Instead of modifying counts, we can use information from lower-order n-grams when higher-order ones are unreliable. Two strategies exist:

Backoff: Use the lower-order model only when the higher-order count is zero. If we've never seen the trigram "the cat ate," back off to the bigram "cat ate."

Interpolation: Always combine evidence from multiple n-gram orders using weighted averaging.

Interpolation

Linear interpolation mixes unigram, bigram, and trigram probabilities:

where:

- : the interpolated probability of word given the two preceding words and

- : interpolation weights that sum to 1 ()

- : unigram probability (how likely is regardless of context)

- : bigram probability (how likely is given only the immediately preceding word)

- : trigram probability (how likely is given both preceding words)

The formula computes a weighted average of three different probability estimates. The unigram term provides a baseline that's always non-zero for known words. The bigram term adds local context. The trigram term captures the full available context. By combining all three, interpolation ensures non-zero probabilities even when higher-order n-grams are missing.

The weights are typically learned from held-out data using the EM algorithm or grid search.

Stupid Backoff

A simpler approach that works surprisingly well for large-scale systems is "stupid backoff." It doesn't produce true probabilities but scores that work well for ranking:

where:

- : score for word given the preceding words

- : shorthand notation for the sequence of words from position to (the context)

- : the full n-gram including both context and the target word

- : count of the full n-gram in the training corpus

- : count of the context (the words preceding )

- : backoff weight (typically 0.4), applied as a penalty when backing off to lower-order n-grams

- : the shorter context used when backing off (drops the oldest word)

The formula is recursive: if the full n-gram has been observed, use the standard relative frequency estimate. If not, multiply by and recursively compute the score using a shorter context. Each backoff step incurs the penalty, so scores decrease the more we back off.

Google used this for their web-scale language models because it's fast and the scores work well for ranking despite not being proper probabilities.

The weight distribution matters. When we favor trigrams (), the probability is higher because the trigram "<s> the cat" appears in our corpus. When we favor unigrams (), we rely more on how often "cat" appears overall, which dilutes the context-specific information.

Interpolation provides a smooth fallback mechanism. Even when the trigram count is zero, the bigram and unigram components contribute to a non-zero probability.

Kneser-Ney Smoothing

The smoothing methods we've seen so far share a common limitation: they treat the backoff distribution as a simple unigram model based on word frequency. But word frequency alone can be misleading. Kneser-Ney smoothing addresses this with two innovations that, together, create the most effective n-gram smoothing method ever developed.

The Problem with Frequency-Based Backoff

To understand why Kneser-Ney matters, consider the phrase "San Francisco." In any corpus about California, the word "Francisco" appears frequently. A standard unigram model would assign it high probability.

But here's the catch: "Francisco" almost always follows "San." It rarely appears in other contexts. If we're backing off from an unseen trigram like "visited beautiful Francisco," a frequency-based unigram model would say "Francisco" is likely. Yet intuitively, we know "Francisco" is an unlikely word to appear after "beautiful" because it almost never starts a new context on its own.

This observation leads to Kneser-Ney's key insight: when backing off, we shouldn't ask "how often does this word appear?" but rather "in how many different contexts does this word appear?"

Innovation 1: Absolute Discounting

The first innovation is straightforward. Instead of using Good-Turing's complex count adjustments, Kneser-Ney subtracts a fixed discount from every observed count:

where:

- : the absolute discounting probability of word given context

- : count of the bigram in the training corpus

- : count of the context word

- : the fixed discount value subtracted from each count (typically 0.75)

- : ensures the discounted count never goes negative

- : an interpolation weight that depends on the context (defined below)

- : a lower-order probability estimate (e.g., unigram probability)

The formula has two terms:

- Discounted probability: The observed count minus , divided by the context count. The ensures we never go negative.

- Backoff contribution: An interpolation weight times a lower-order probability.

The discount is typically 0.75, a value derived from theoretical analysis of Good-Turing estimates. By subtracting a fixed amount rather than a percentage, absolute discounting treats all observed n-grams more uniformly. An n-gram seen 5 times loses 0.75 (15%), while one seen 2 times loses 0.75 (37.5%). This makes sense: rare observations are less reliable and should be discounted more aggressively in relative terms.

Innovation 2: Continuation Probability

The second innovation is where Kneser-Ney truly shines. For the backoff distribution , it doesn't use raw word frequency. Instead, it uses continuation probability: the proportion of unique contexts in which a word appears.

where:

- : the continuation probability of word

- : the number of unique words that precede in the corpus (i.e., how many different contexts appears in)

- : the total number of unique bigram types in the corpus

- : count of the bigram

The vertical bars denote set cardinality (the number of elements in the set). The numerator counts distinct preceding words, not total occurrences.

Let's unpack the intuition:

- Numerator: Count how many unique words precede . For "Francisco," this might be just 1 (only "San" precedes it). For "the," it might be hundreds.

- Denominator: The total number of unique bigram types in the corpus, serving as a normalizing constant.

Returning to our example: "Francisco" has high frequency but low continuation count (appears after few unique words). "The" has high frequency and high continuation count (appears after many unique words). When backing off, "the" deserves higher probability than "Francisco" because it's a more versatile word that genuinely appears in diverse contexts.

Putting It Together: The Full Formula

The complete Kneser-Ney formula for the highest-order n-gram combines both innovations:

where:

- : the Kneser-Ney smoothed probability of word given the preceding words

- : shorthand for the context sequence , the preceding words

- : the full n-gram including the target word,

- : count of the full n-gram in the training corpus

- : count of the context (how often the word sequence appears)

- : discount value (typically 0.75)

- : interpolation weight for this context (defined below)

- : the recursive lower-order Kneser-Ney probability using a shorter context

The interpolation weight ensures probability mass is conserved. It equals the total amount discounted from all observed continuations:

where:

- : the interpolation weight for context

- : the discount value (typically 0.75)

- : total count of the context sequence

- : the number of unique words that follow this context in the training corpus

This formula says: take the discount , multiply by the number of unique words that follow this context, and divide by the total context count. The result is exactly the probability mass we "stole" from observed n-grams, which we now redistribute through the backoff distribution.

For lower-order distributions (used in the recursive backoff), raw counts are replaced with continuation counts. This is what makes the "San Francisco" example work correctly: "Francisco" has low continuation count, so it receives low probability in the backoff distribution despite its high raw frequency.

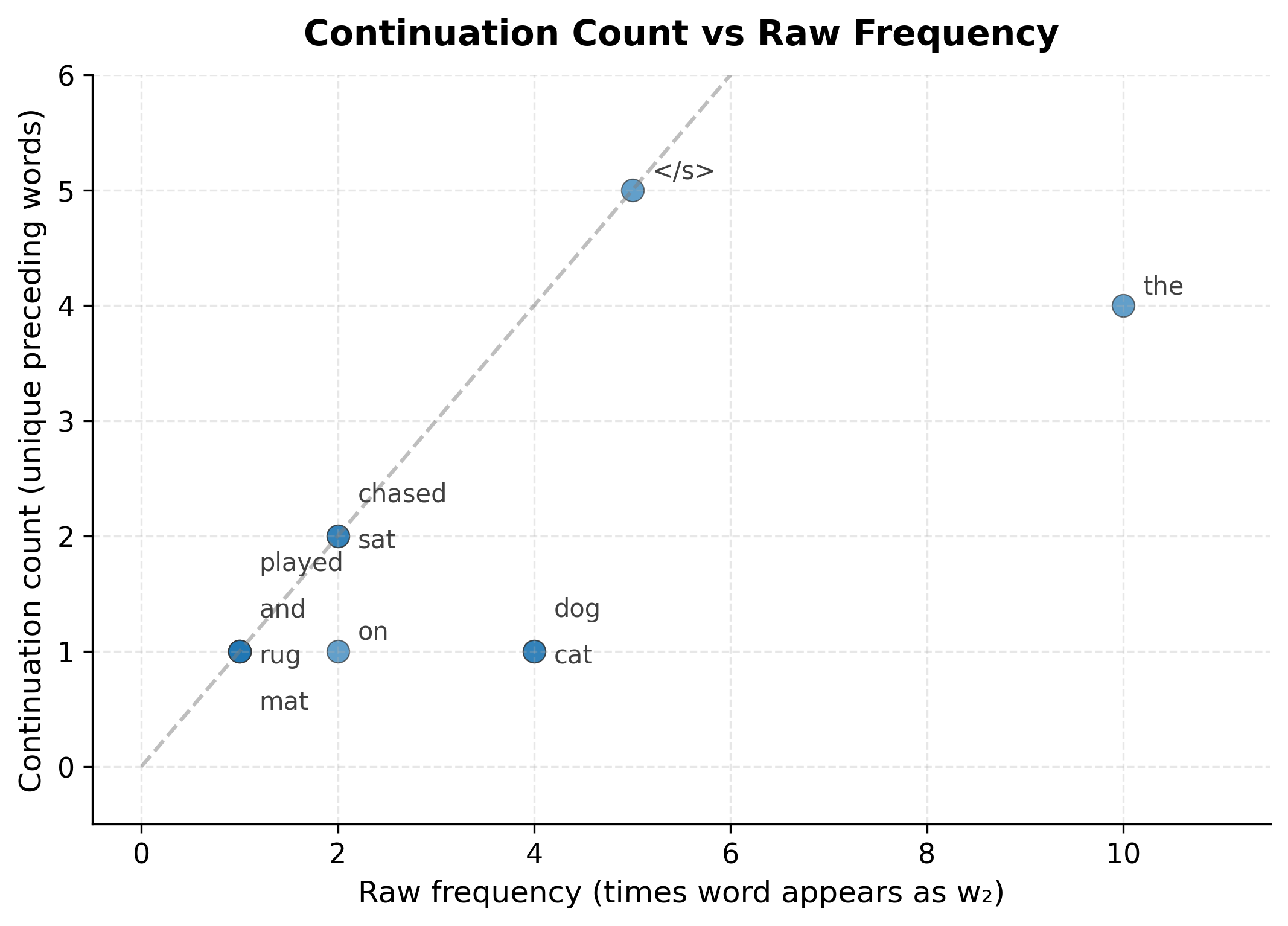

Let's examine the continuation counts and compute Kneser-Ney probabilities for several test bigrams:

The continuation counts reveal which words are versatile. Words like "the" and "cat" appear after multiple different words, giving them higher continuation probability. The word "" (end of sentence) also has high continuation count because every sentence ends with it.

The scatter plot illustrates Kneser-Ney's key insight. Words near or above the diagonal line are "versatile," appearing in many different contexts relative to their frequency. Words below the line are context-dependent, appearing frequently but in limited contexts. In a larger corpus, "Francisco" would appear far below the diagonal (high frequency, low continuation count), while common function words like "the" would appear on or above it.

Kneser-Ney assigns non-zero probability to the unseen bigram "the elephant" through the continuation probability term, while keeping observed bigrams at reasonable levels. The discount of 0.75 is subtracted from each observed count, and the freed probability mass flows to the continuation distribution.

Modified Kneser-Ney

Modified Kneser-Ney improves on the original by using three different discount values based on the count:

where:

- : the discount to apply to n-grams with count

- : discount for singletons (n-grams appearing exactly once)

- : discount for doubletons (n-grams appearing exactly twice)

- : discount for n-grams appearing three or more times

These discount values are estimated from the training data using the frequency of frequencies:

where:

- : a normalization factor based on singleton and doubleton counts

- : number of n-grams appearing exactly once (singletons)

- : number of n-grams appearing exactly twice (doubletons)

- : number of n-grams appearing exactly three times

- : number of n-grams appearing exactly four times

The formulas derive from Good-Turing theory. Each discount is computed as , which adjusts the base count by a factor that depends on how the frequency of frequencies changes. The factor normalizes for the overall shape of the distribution.

The intuition is that n-grams seen once are more likely to be noise than those seen twice, which are more likely to be noise than those seen three or more times. The discounts typically increase with count (), but since lower counts are smaller to begin with, the relative impact is greater for rare n-grams. Subtracting 0.7 from a count of 1 removes 70% of the probability mass, while subtracting 1.3 from a count of 10 removes only 13%.

Computing the discount parameters from our corpus statistics:

The Y factor normalizes based on the ratio of singletons to doubletons. With our small corpus, the discount values are at their boundary conditions. On larger corpora, typical values are around , , and . The progression makes intuitive sense: we discount singletons more aggressively because they're more likely to be noise, while n-grams seen three or more times are more reliable and get smaller relative discounts.

Comparing Smoothing Methods

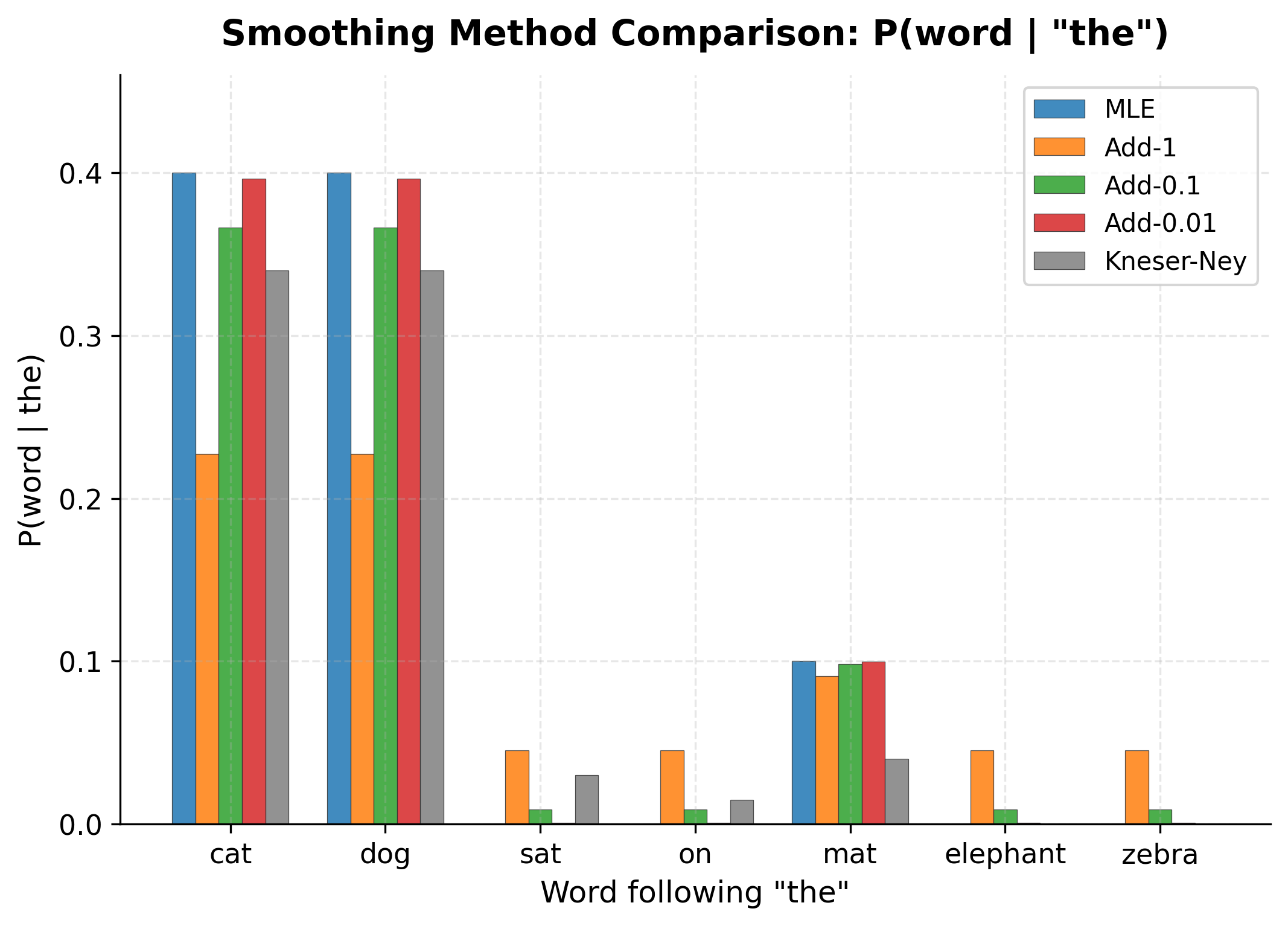

Now let's put all these methods side by side and compare how they handle the same probability estimation task. We'll compute probabilities for words following "the," including both observed and unseen words.

The chart reveals the trade-offs clearly. MLE gives the highest probabilities to observed words but zeros for unseen ones. Add-1 smoothing flattens everything too much. Add-0.01 and Kneser-Ney strike a better balance, keeping observed words relatively high while providing coverage for unseen words.

The exact probability values are shown in the table below:

The numbers confirm our observations from the chart. For observed words like "cat" and "dog," MLE gives the highest probability, but Add-1 drops it dramatically. Kneser-Ney maintains probabilities closer to MLE for observed words while still providing coverage for unseen ones like "elephant" and "zebra." This balance is why Kneser-Ney became the standard for production language models.

Limitations and Impact

Smoothing techniques revolutionized n-gram language modeling but are not without constraints. Understanding both their limitations and historical impact provides context for why neural language models eventually superseded them.

Limitations

Smoothing techniques, despite their sophistication, have inherent limitations:

- Fixed context window: All n-gram smoothing methods are bounded by the Markov assumption. No amount of smoothing helps when the relevant context is beyond the n-gram window.

- Vocabulary dependence: Performance degrades with vocabulary size. As grows, the number of possible unseen n-grams explodes.

- Domain sensitivity: Smoothing parameters tuned on one domain may perform poorly on another. A model trained on news text with optimal smoothing for that domain may still struggle with social media text.

- No semantic awareness: Smoothing treats "the cat ate" and "the cat flew" identically if both are unseen. It cannot use semantic knowledge that cats are more likely to eat than fly.

Impact

Despite these limitations, smoothing techniques were foundational to practical NLP:

- Speech recognition: Kneser-Ney smoothing powered speech recognition systems for decades, enabling reliable transcription even for novel word combinations.

- Machine translation: Statistical MT systems relied heavily on smoothed language models to score translation candidates.

- Spell correction: Smoothed models help distinguish between plausible and implausible word sequences for context-aware spelling correction.

- Established evaluation practices: The development of smoothing techniques led to rigorous evaluation methods like perplexity comparison on held-out data.

The techniques in this chapter represent the pinnacle of count-based language modeling. They squeezed remarkable performance from simple statistics. But they also revealed the ceiling: no matter how clever the smoothing, n-gram models cannot capture long-range dependencies or semantic similarity. This limitation motivated the shift to neural language models, which learn continuous representations that naturally generalize to unseen word combinations.

Summary

Smoothing techniques solve the zero probability problem in n-gram language models by redistributing probability mass from observed to unseen events.

Key takeaways:

- Laplace (add-one) smoothing is simple but steals too much probability from observed events

- Add-k smoothing improves by using smaller constants, with tuned on held-out data

- Good-Turing smoothing uses frequency of frequencies to estimate probability mass for unseen events

- Interpolation combines evidence from multiple n-gram orders using learned weights

- Kneser-Ney smoothing uses absolute discounting and continuation probability, making it the gold standard for n-gram models

- Modified Kneser-Ney refines discounting with count-dependent values

The choice of smoothing method matters significantly. On large corpora, Kneser-Ney typically outperforms simpler methods by 10-20% in perplexity. For small corpora or quick experiments, add-k smoothing provides a reasonable baseline with minimal implementation effort.

These techniques represent the culmination of decades of statistical NLP research. While neural language models have largely superseded n-gram models for most applications, understanding smoothing provides essential intuition about probability estimation, the bias-variance trade-off, and the importance of handling unseen events, concepts that remain central to modern NLP.

Key Parameters

When implementing smoothing techniques, these parameters have the most impact on model performance:

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| (add-k smoothing) | 0.001 - 0.5 | Controls probability mass given to unseen events. Smaller values stay closer to MLE; larger values flatten the distribution. Tune on held-out data. |

| (Kneser-Ney discount) | 0.75 | Fixed discount subtracted from all counts. The standard value of 0.75 works well across most corpora. |

| (Modified KN) | 0.7, 1.0, 1.3 | Count-dependent discounts. Computed from corpus statistics using the formulas above. No manual tuning needed. |

| weights (interpolation) | Sum to 1.0 | Control contribution of each n-gram order. Learn from held-out data using EM or grid search. Higher-order weights should generally be larger. |

| (stupid backoff) | 0.4 | Backoff penalty applied when falling back to lower-order n-grams. The value 0.4 was empirically determined by Google. |

| (n-gram order) | 3 - 5 | Higher orders capture more context but suffer more from sparsity. Trigrams are common; 5-grams require very large corpora. |

Comments