Master text normalization techniques including Unicode NFC/NFD/NFKC/NFKD forms, case folding vs lowercasing, diacritic removal, and whitespace handling. Learn to build robust normalization pipelines for search and deduplication.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Text Normalization

In the previous chapter, we saw how a single character like "é" can be represented in multiple ways: as a single precomposed code point (U+00E9) or as a base letter plus a combining accent (U+0065 + U+0301). Both look identical on screen, but Python considers them different strings. This seemingly minor issue can break string matching, corrupt search results, and introduce subtle bugs into your NLP pipelines.

Text normalization is the process of transforming text into a consistent, canonical form. It goes beyond encoding to address the fundamental question: when should two different byte sequences be considered the "same" text? This chapter covers Unicode normalization forms, case handling, whitespace cleanup, and building robust normalization pipelines.

Why Normalization Matters

Consider a simple task: searching for the word "café" in a document. Without normalization, your search might miss matches because the document uses a different Unicode representation.

The strings are visually identical but computationally different. This creates problems across NLP:

- Search: Users searching for "café" won't find documents containing the decomposed form

- Deduplication: Duplicate detection fails when the same text uses different representations

- Tokenization: Tokenizers may split decomposed characters incorrectly

- Embeddings: Identical words may receive different vector representations

Unicode Normalization Forms

The Unicode standard defines four normalization forms to address representation ambiguity. Each form serves different purposes.

Unicode normalization transforms text into a canonical form where equivalent strings have identical code point sequences. The four forms (NFC, NFD, NFKC, NFKD) differ in whether they compose or decompose characters and whether they apply compatibility mappings.

NFC: Canonical Composition

NFC (Normalization Form Canonical Composition) converts text to its shortest representation by combining base characters with their accents into single precomposed characters where possible.

NFC is the most commonly used normalization form. It produces the most compact representation and matches what most users expect when they type accented characters.

NFD: Canonical Decomposition

NFD (Normalization Form Canonical Decomposition) does the opposite: it breaks precomposed characters into their base character plus combining marks.

NFD is useful when you need to manipulate accents separately from base characters, such as removing diacritics or analyzing character components.

NFKC and NFKD: Compatibility Normalization

The "K" forms apply compatibility decomposition in addition to canonical normalization. This maps characters that are semantically equivalent but visually distinct.

Compatibility equivalence groups characters that represent the same abstract character but differ in appearance or formatting. Examples include full-width vs. half-width characters, ligatures vs. separate letters, and superscripts vs. regular digits.

NFKC is aggressive. It converts the "fi" ligature to separate "f" and "i" characters, expands the circled digit to just "1", and converts full-width characters to their ASCII equivalents. This is useful for search and comparison but destroys formatting information.

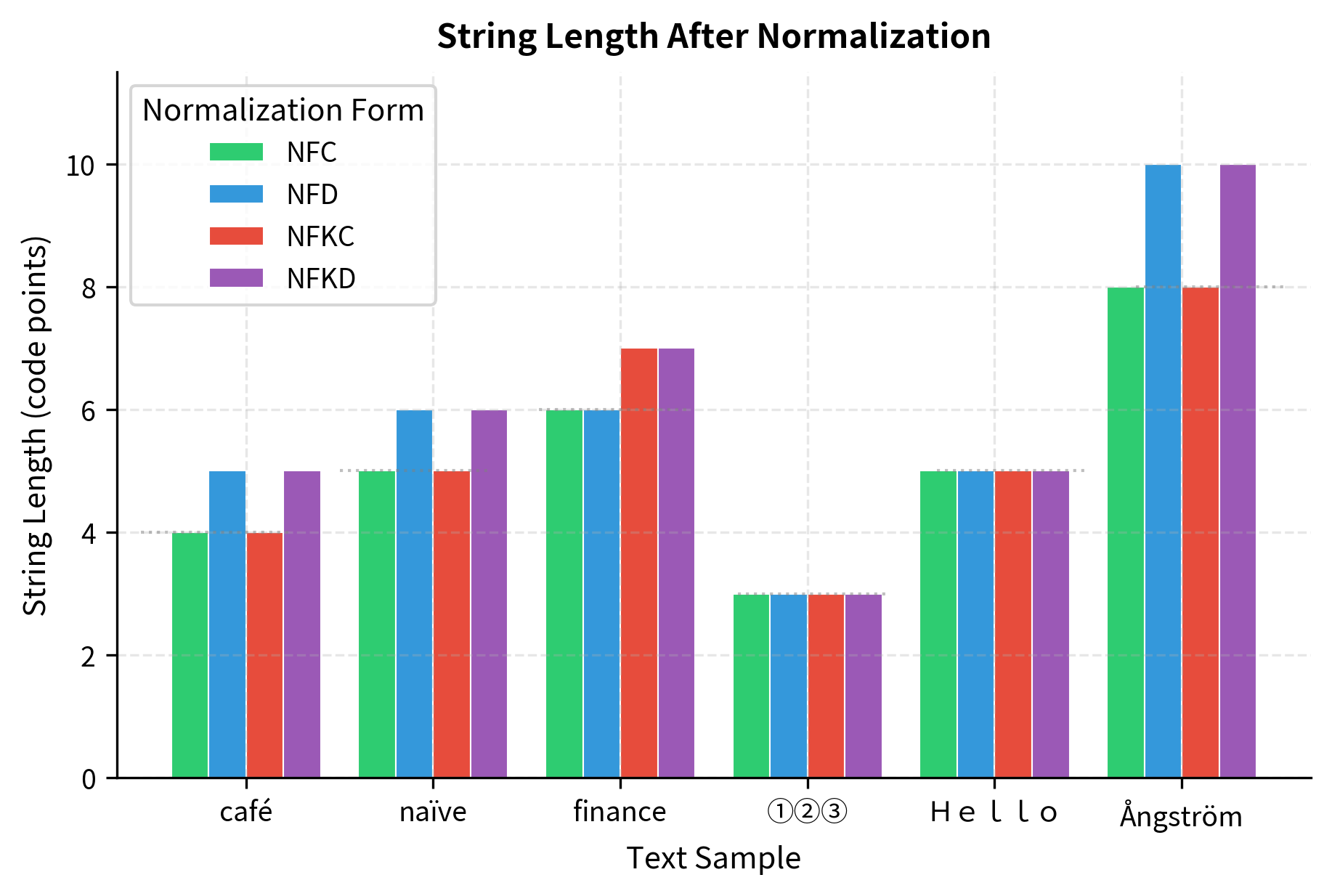

The table below shows how each normalization form transforms different input characters. NFC and NFD are canonical forms that preserve character identity, while NFKC and NFKD apply compatibility mappings that may change the character representation.

| Input | NFC | NFD | NFKC | NFKD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| café (decomposed) | café | café | café | café |

| e + ́ (combining) | é | e + ́ | é | e + ́ |

| fi (ligature) | fi | fi | fi | fi |

| ① (circled) | ① | ① | 1 | 1 |

| hi (full-width) | hi | hi | hi | hi |

The canonical forms (NFC, NFD) preserve ligatures and special characters, changing only the internal representation. The compatibility forms (NFKC, NFKD) aggressively normalize to base characters, expanding ligatures and converting full-width to half-width.

Choosing a Normalization Form

The right form depends on your use case:

| Use Case | Recommended Form | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| General text storage | NFC | Compact, preserves visual appearance |

| Accent-insensitive search | NFD then strip marks | Easy to remove combining characters |

| Full-text search | NFKC | Matches variant representations |

| Security (username comparison) | NFKC | Prevents homograph attacks |

| Preserving formatting | NFC | Keeps ligatures and special forms |

The length differences reveal how each form handles the input. NFD produces the longest output because it decomposes characters into base letters plus combining marks. NFC and NFKC produce shorter outputs by composing characters, with NFKC additionally expanding the ligature "fi" into two separate characters.

The chart reveals important patterns. Text with combining diacritics (café, naïve, Ångström) shows significant length increase under NFD decomposition. Full-width characters (Hello) and circled digits (①②③) shrink dramatically under NFKC/NFKD as they're mapped to their ASCII equivalents. The ligature "fi" in "finance" expands from one character to two under compatibility normalization.

Case Folding vs. Lowercasing

Case-insensitive comparison seems simple: just convert both strings to lowercase. But Unicode makes this surprisingly complex.

The Problem with Simple Lowercasing

The German "ß" uppercases to "SS" (two characters), and lowercasing "SS" gives "ss", not "ß". Round-tripping through case conversion changes the string. This is not a bug; it reflects German orthographic rules where "ß" traditionally had no uppercase form. While Unicode 5.1 (2008) added the capital ẞ (U+1E9E), Python's upper() still converts to "SS" for compatibility with the traditional standard.

Case Folding

Case folding is a Unicode operation designed for case-insensitive comparison. Unlike simple lowercasing, case folding handles language-specific mappings and ensures that equivalent strings compare equal regardless of their original case.

Python's str.casefold() method implements Unicode case folding:

With casefold(), all four variations of "street" in German normalize to the same string, enabling correct case-insensitive comparison.

The following table shows how many distinct strings remain after applying lower() versus casefold() to groups of equivalent words. The ideal is 1 (all variants unified to a single canonical form):

lower() vs casefold() for case-insensitive string matching across languages.| Word Group | Variants | lower() distinct | casefold() distinct |

|---|---|---|---|

| German "street" | Straße, STRASSE, straße, strasse, STRAßE | 2 | 1 |

| German "size" | Größe, GRÖSSE, größe, groesse, GROESSE | 3 | 2 |

| Greek sigma | σ, ς, Σ | 2 | 1 |

| Mixed case | Hello, HELLO, hello, HeLLo | 1 | 1 |

| Turkish I | Istanbul, ISTANBUL, istanbul, İstanbul | 2 | 2 |

For German words with "ß", casefold() correctly unifies all variants to a single canonical form, while lower() leaves two distinct values. Greek sigma variants (σ, ς, Σ) are particularly interesting: casefold() maps them all to the same form, recognizing that they represent the same letter in different positions. Standard English words show identical behavior for both methods, confirming that casefold() is a superset of lower() functionality. Note that Turkish requires locale-aware handling for correct dotted/dotless I normalization, which neither method provides automatically.

Language-Specific Case Rules

Some case conversions depend on language context:

In Turkish, "I" lowercases to "ı" (dotless) and "i" uppercases to "İ" (dotted). Python's default case operations follow English rules, which can cause problems with Turkish text. For locale-aware case conversion, you need specialized libraries.

Accent and Diacritic Handling

Many NLP applications benefit from accent-insensitive matching. A user searching for "resume" should probably find "résumé".

Removing Diacritics

The standard approach uses NFD normalization followed by filtering:

This technique decomposes accented characters into base letters plus combining marks, removes the marks, and recomposes. The result is plain ASCII-compatible text.

Preserving Semantic Distinctions

Be careful: removing diacritics can change meaning in some languages.

For search applications, you might want to match both forms. For translation or language understanding, preserving diacritics is essential.

The collision rate when stripping diacritics varies dramatically by language:

| Language | Collision Rate | Collisions / Total Words | Example Collisions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spanish | 50% | 10 / 20 | año/ano (year/anus), sí/si (yes/if) |

| French | 47% | 7 / 15 | où/ou (where/or), côte/cote (coast/quote) |

| German | 50% | 6 / 12 | schön/schon (beautiful/already), drücken/drucken (press/print) |

| Portuguese | 50% | 6 / 12 | pôde/pode (could/can), pôr/por (put/by) |

| English | 50% | 5 / 10 | résumé/resume, café/cafe |

Spanish and French use diacritics extensively to distinguish word meanings. German umlauts often differentiate semantically different words. English treats diacritics largely as optional styling for loanwords, but stripping them still causes collisions with the non-diacritical forms. These numbers underscore why blanket diacritic removal can be problematic for multilingual NLP applications.

Whitespace Normalization

Whitespace seems simple, but Unicode defines many whitespace characters beyond the familiar space and tab.

Notice that the zero-width space (U+200B) is not considered whitespace by Python's isspace(). These invisible characters can cause subtle bugs.

The following table shows the UTF-8 byte sizes and isspace() behavior for common Unicode whitespace characters:

isspace() detection.| Character | Code Point | UTF-8 Bytes | isspace() |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space | U+0020 | 1 | ✓ |

| Tab | U+0009 | 1 | ✓ |

| Newline | U+000A | 1 | ✓ |

| Carriage Return | U+000D | 1 | ✓ |

| No-Break Space | U+00A0 | 2 | ✓ |

| En Space | U+2002 | 3 | ✓ |

| Em Space | U+2003 | 3 | ✓ |

| Thin Space | U+2009 | 3 | ✓ |

| Zero Width Space | U+200B | 3 | ✗ |

| Ideographic Space | U+3000 | 3 | ✓ |

The byte size variation has practical implications. A document using ideographic spaces (common in CJK text) will be larger than one using standard ASCII spaces. Zero-width characters, despite being invisible, still consume 3 bytes each in UTF-8, and they can accumulate when copying text from web pages or PDFs. Note that zero-width space is not detected by isspace(), which can cause subtle matching bugs.

Normalizing Whitespace

A robust whitespace normalizer should:

- Convert all whitespace variants to standard spaces

- Collapse multiple spaces into one

- Strip leading and trailing whitespace

- Optionally handle zero-width characters

The normalizer reduced the string from 18 characters to 17 by converting the various Unicode spaces (no-break space, ideographic space) to standard spaces, removing the zero-width space entirely, and collapsing consecutive spaces into single spaces. This produces consistent, predictable whitespace that won't cause matching failures.

Ligature Expansion

Ligatures are single characters that represent multiple letters joined together. They're common in typeset text and can cause matching problems.

NFKC handles most Latin ligatures correctly. However, some characters like "æ" and "œ" are considered distinct letters in some languages (Danish, French) rather than ligatures, so NFKC preserves them.

The following table shows common ligatures, their Unicode code points, and their expanded forms. Note the large code point gap between ligatures in the Alphabetic Presentation Forms block (U+FB00-FB4F) and their ASCII expansions (U+0000-007F). This gap explains why naive string comparison fails without normalization:

| Ligature | Code Point | Expansion | Expansion Code Points | Unicode Block |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fi | U+FB01 | fi | U+0066 U+0069 | Alphabetic Presentation Forms |

| fl | U+FB02 | fl | U+0066 U+006C | Alphabetic Presentation Forms |

| ff | U+FB00 | ff | U+0066 U+0066 | Alphabetic Presentation Forms |

| ffi | U+FB03 | ffi | U+0066 U+0066 U+0069 | Alphabetic Presentation Forms |

| ffl | U+FB04 | ffl | U+0066 U+0066 U+006C | Alphabetic Presentation Forms |

| ſt | U+FB05 | st | U+0073 U+0074 | Alphabetic Presentation Forms |

| œ | U+0153 | œ (preserved) | — | Latin Extended-A |

| æ | U+00E6 | æ (preserved) | — | Latin-1 Supplement |

| Œ | U+0152 | Œ (preserved) | — | Latin Extended-A |

The Latin f-ligatures (fi, fl, ff, ffi, ffl, ſt) are expanded by NFKC because they're typographic variants. However, "æ" and "œ" are preserved because they function as distinct letters in languages like Danish, Norwegian, and French.

The code point data reveals why ligatures cause string matching problems. The "fi" ligature (U+FB01) and its expansion "fi" (U+0066, U+0069) are separated by over 64,000 code points in Unicode space. Characters like "æ" and "œ" sit in the Latin-1 Supplement block, much closer to their ASCII equivalents, reflecting their status as distinct letters rather than purely typographic ligatures. Without normalization, a search for "find" will never match "find" even though they're semantically identical.

Full-Width to Half-Width Conversion

East Asian text often uses full-width versions of ASCII characters. These take up the same width as CJK characters, creating visual alignment in mixed text.

Each full-width character maps to its ASCII equivalent by subtracting a fixed offset (0xFEE0) from the code point. The ideographic space (U+3000) is a special case that maps to the regular space (U+0020). This conversion is essential when processing East Asian text that mixes CJK characters with Latin letters and digits.

NFKC normalization also handles full-width to half-width conversion:

The NFKC normalization produces identical results to the manual conversion function, confirming that NFKC handles full-width to half-width mapping as part of its compatibility normalization. This means you can use NFKC for comprehensive normalization without implementing character-specific conversion logic, simplifying your normalization pipeline.

Building a Normalization Pipeline

Real-world text normalization combines multiple techniques. The order of operations matters.

The two normalizers produce notably different outputs from the same input. The search normalizer aggressively transforms the text for maximum matching flexibility: it converts full-width characters to ASCII, strips accents, folds case, expands the ligature "fi" to "fi", and collapses all whitespace variants. The storage normalizer preserves the original character forms while only standardizing whitespace, maintaining the text's visual fidelity for display purposes.

Pipeline Order Matters

The order of normalization steps can affect results:

In this case, the order doesn't matter. But with more complex transformations involving case-sensitive patterns or locale-specific rules, order can be significant. Always test your pipeline with representative data.

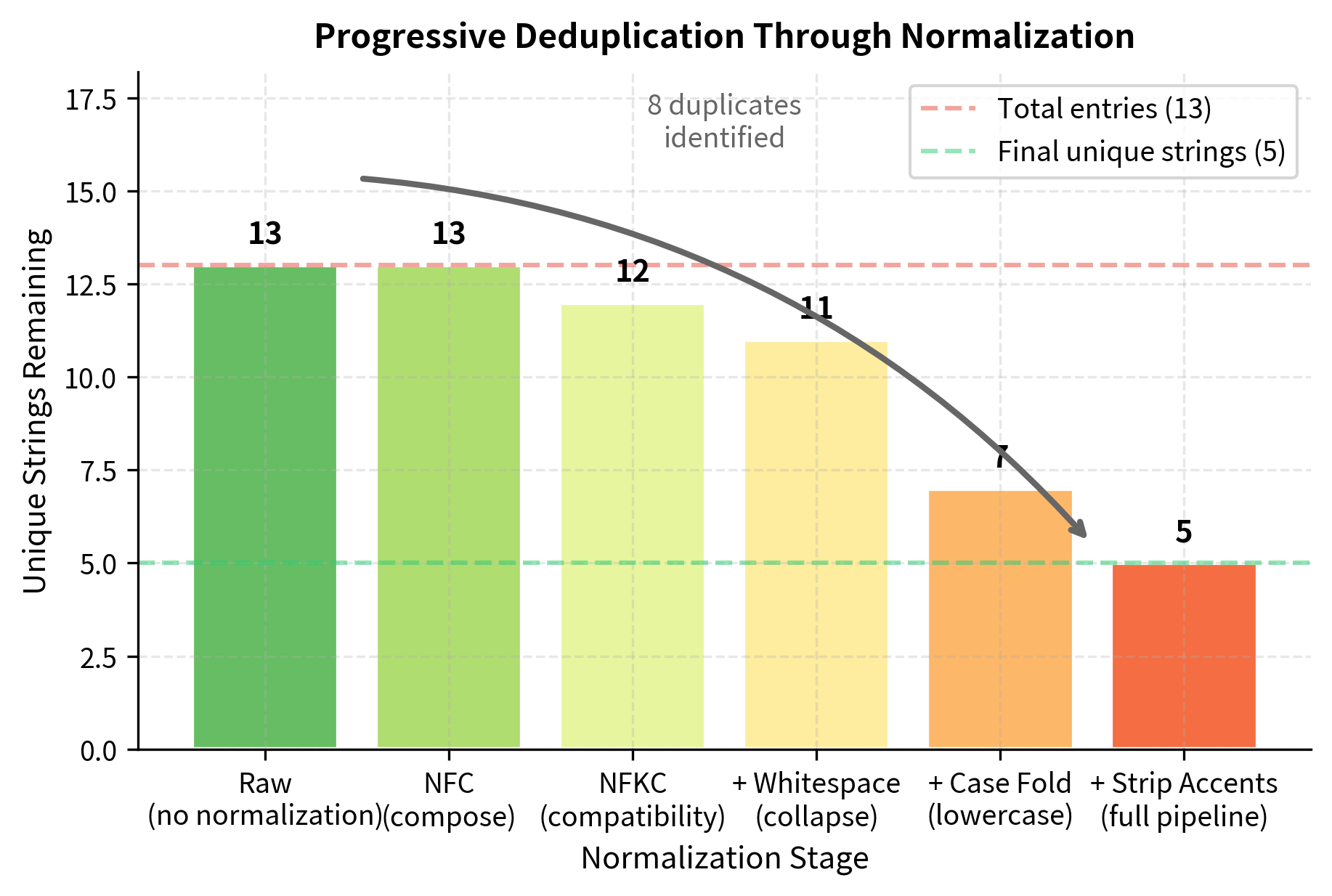

Practical Example: Deduplication

Let's apply normalization to a real task: finding duplicate entries in a dataset.

The normalizer correctly groups variations of "Société Générale" and "Apple Inc." together. It also groups "Müller" with "Mueller" since stripping accents converts "ü" to "u".

The visualization shows how each normalization step progressively reduces the number of unique strings. Raw text shows 13 distinct entries, but after full normalization, only 5 unique strings remain. Each step contributes to duplicate detection: NFKC handles full-width characters, whitespace normalization catches extra spaces, case folding unifies capitalization variants, and accent stripping converts "ü" to "u". The remaining 5 strings differ due to punctuation ("Apple Inc." vs "Apple Inc") and German spelling conventions ("Mueller" as the ue-spelling vs "Müller" which becomes "Muller" after accent stripping).

The table below traces the transformation of "Société Générale" through a complete normalization pipeline:

| Stage | Output | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Raw Input | "Société Générale" | Various encodings and representations |

| Unicode (NFKC) | "Société Générale" | Canonical form, ligatures expanded |

| Whitespace | "Société Générale" | Spaces collapsed, zero-width removed |

| Case Fold | "société générale" | Case-insensitive comparison ready |

| Strip Accents | "societe generale" | Accent-insensitive matching ready |

Each stage addresses a specific type of variation. The final output is a canonical form suitable for search and comparison. All representations of this company name will normalize to the same string.

Limitations and Challenges

Text normalization is powerful but not perfect. Consider these limitations when designing your pipeline:

- Information loss: Aggressive normalization destroys information. Stripping accents loses the distinction between "resume" (to continue) and "résumé" (CV). Case folding loses the distinction between proper nouns and common words.

- Language specificity: No single normalization strategy works for all languages. Turkish case rules differ from English. Chinese has no case. Some scripts have no concept of accents.

- Context dependence: The right normalization depends on your task. Search benefits from aggressive normalization. Machine translation needs to preserve source text exactly.

- Irreversibility: Most normalization operations cannot be undone. Once you've stripped accents or folded case, the original information is gone.

- Edge cases: Unicode is vast and complex. New characters are added regularly. Your normalization code may not handle every possible input correctly.

Key Functions and Parameters

When working with text normalization in Python, these are the essential functions and their most important parameters:

-

unicodedata.normalize(form, text): Applies Unicode normalization to a string. Theformparameter specifies the normalization form:'NFC'(canonical composition, default for storage),'NFD'(canonical decomposition, useful for accent stripping),'NFKC'(compatibility composition, aggressive, for search), or'NFKD'(compatibility decomposition). -

unicodedata.category(char): Returns a two-letter category code for a Unicode character. Common categories include'Mn'(Mark, Nonspacing, for combining diacritics),'Cc'(control characters), and'Zs'(space separator). Useful for filtering specific character types during normalization. -

str.casefold(): Returns a casefolded copy of the string for case-insensitive comparison. More aggressive thanlower(), handles special cases like German "ß" → "ss". Preferred overlower()for Unicode-aware case-insensitive matching. -

str.lower()vsstr.casefold(): Uselower()for display (standard Unicode lowercasing) andcasefold()for comparison (full Unicode case folding that handles language-specific mappings). -

re.sub(pattern, replacement, text): Essential for whitespace normalization. Common patterns includer'[\u00A0\u2000-\u200A\u202F\u205F\u3000]'for various Unicode spaces,r'[\u200B-\u200D\uFEFF]'for zero-width characters, andr' +'for multiple consecutive spaces.

Summary

Text normalization transforms text into consistent, comparable forms. We covered:

- Unicode normalization forms: NFC composes, NFD decomposes, NFKC and NFKD add compatibility mappings

- Case folding: Use

casefold()for case-insensitive comparison, notlower() - Diacritic handling: NFD decomposition plus filtering removes accents

- Whitespace normalization: Unicode has many whitespace characters beyond space and tab

- Ligature expansion: NFKC expands most typographic ligatures

- Full-width conversion: NFKC converts full-width ASCII to standard ASCII

Key takeaways:

- NFC is the default choice for general text storage

- NFKC with casefold is best for search and comparison

- Always normalize before comparing strings for equality

- Normalization order matters: plan your pipeline carefully

- Test with representative data: edge cases will surprise you

- Preserve originals: keep unnormalized text when possible

In the next chapter, we'll explore tokenization, the process of breaking text into meaningful units for further processing.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about text normalization.

Comments