Master regular expressions for text processing, covering metacharacters, quantifiers, lookarounds, and practical NLP patterns. Learn to extract emails, URLs, and dates while avoiding performance pitfalls.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Regular Expressions

Text data is messy. Emails hide in paragraphs, phone numbers appear in a dozen formats, and dates refuse to follow any single convention. Before you can extract meaning from text, you need to find patterns within it. Regular expressions give you a powerful, compact language for describing these patterns. A single regex can match thousands of variations of an email address, validate input formats, or extract structured data from unstructured text.

This chapter teaches you to read and write regular expressions fluently. You'll learn the syntax that makes regex both powerful and cryptic, understand when to use them versus simpler alternatives, and build practical patterns for common NLP tasks. By the end, you'll wield regex as a precision tool for text manipulation.

What Are Regular Expressions?

A regular expression (regex) is a sequence of characters that defines a search pattern. Think of it as a tiny programming language embedded within Python, specialized for matching and manipulating text.

A regular expression is a formal language for describing patterns in strings. It uses special characters called metacharacters to represent classes of characters, repetition, position, and grouping, allowing a single pattern to match many different strings.

The power of regex comes from its expressiveness. The pattern \b[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Z|a-z]{2,}\b looks intimidating, but it matches most email addresses in a single line. Without regex, you'd need dozens of lines of conditional logic to achieve the same result.

Let's start with a simple example:

The pattern cat matches the literal characters c, a, t in sequence. It found two matches: "cat" as a standalone word and "cat" inside "catalog". Let's verify the match positions:

The regex found "cat" as a standalone word and "cat" inside "catalog". This illustrates a key point: by default, regex matches anywhere in the text, including inside other words. We'll learn how to match whole words only using word boundaries.

The re Module

Python's re module provides the interface for working with regular expressions. Before diving into pattern syntax, let's understand the main functions you'll use:

Each function serves a different purpose. Use search() when you only need the first match, findall() when you want a simple list of matched strings, finditer() when you need position information or groups, sub() for replacements, and split() to break text at pattern boundaries.

Raw Strings

Notice the r prefix before pattern strings: r'\w+@\w+'. This creates a raw string where backslashes are treated literally. Without it, Python interprets backslashes as escape sequences before the regex engine sees them.

Always use raw strings for regex patterns. It's a habit that will save you from subtle bugs.

Metacharacters: The Building Blocks

Regular expressions use special characters called metacharacters to represent patterns. These characters have meaning beyond their literal value. While literal characters like a or 5 match themselves, metacharacters like ., *, and [] define rules for what to match. Mastering these building blocks is the key to writing effective patterns.

The Dot: Match Any Character

The dot . matches any single character except a newline:

The dot matched 'a', 'o', 'u', '@', and '9', but not the newline. To match newlines too, use the re.DOTALL flag or the pattern [\s\S].

Character Classes: Matching Sets

Square brackets define a character class, matching any single character from the set:

Negated Character Classes

A caret ^ at the start of a character class negates it, matching any character NOT in the set:

Shorthand Character Classes

Regex provides convenient shortcuts for common character classes:

The following table summarizes the most common regex character classes:

| Shorthand | Equivalent | Description |

|---|---|---|

\d | [0-9] | Any digit |

\D | [^0-9] | Any non-digit |

\w | [a-zA-Z0-9_] | Word character |

\W | [^a-zA-Z0-9_] | Non-word character |

\s | [ \t\n\r\f\v] | Whitespace |

\S | [^ \t\n\r\f\v] | Non-whitespace |

. | (any except \n) | Any character |

Note that uppercase versions match the complement (negation) of their lowercase counterparts.

Quantifiers: How Many Times?

Quantifiers specify how many times the preceding element should match. They range from simple repetition (*, +, ?) to precise bounds ({n}, {n,m}). Understanding quantifiers is essential because they determine whether your pattern matches once, multiple times, or not at all.

Basic Quantifiers

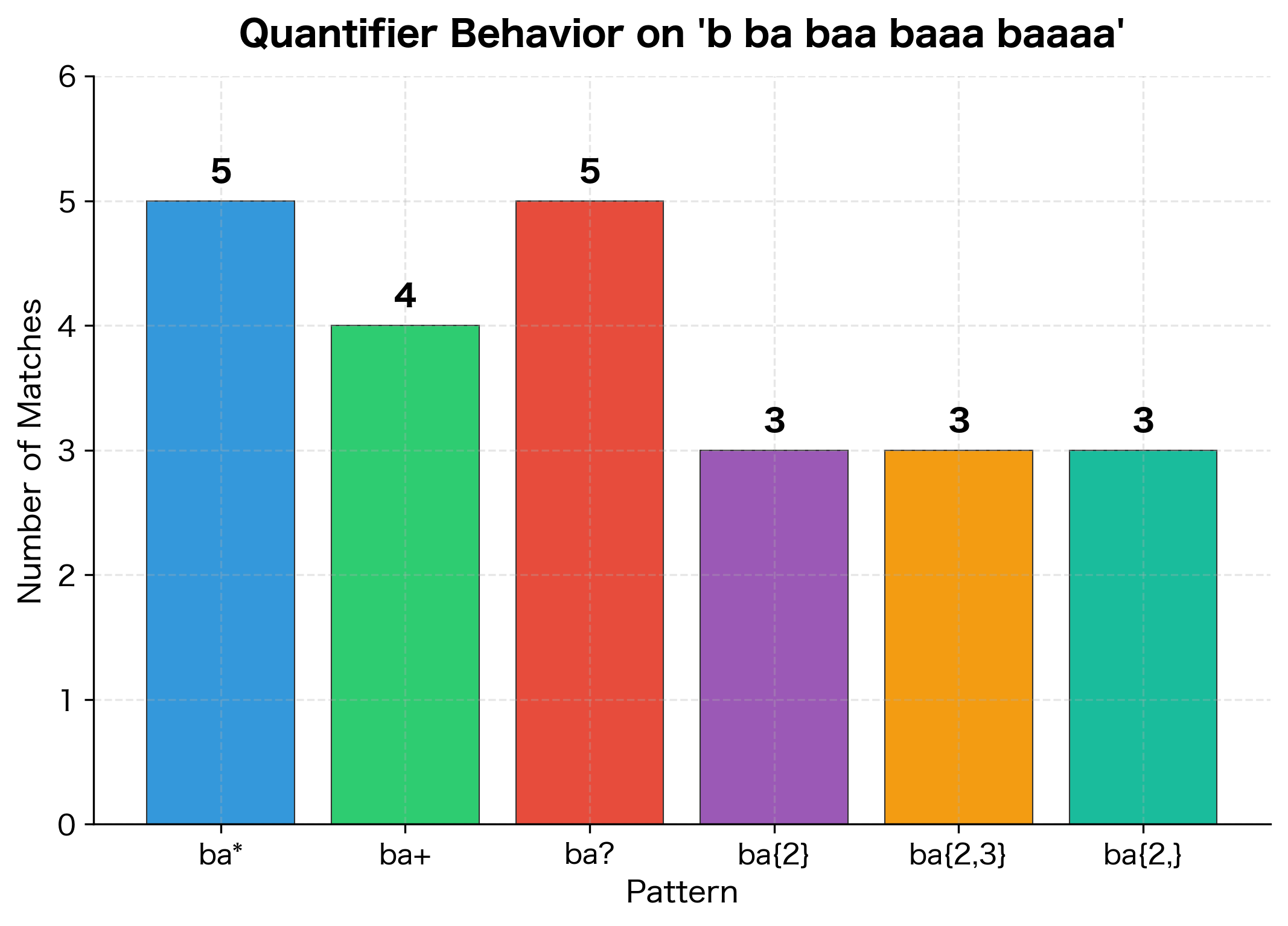

The visualization shows how quantifiers dramatically affect matching behavior. Notice that ba* finds 5 matches because it accepts zero 'a's (matching just 'b'), while ba+ finds only 4 because it requires at least one 'a'. The bounded quantifiers {2}, {2,3}, and {2,} are more selective, matching only strings with specific repetition counts.

Greedy vs. Lazy Matching

By default, quantifiers are greedy: they match as much as possible. Adding ? after a quantifier makes it lazy, matching as little as possible.

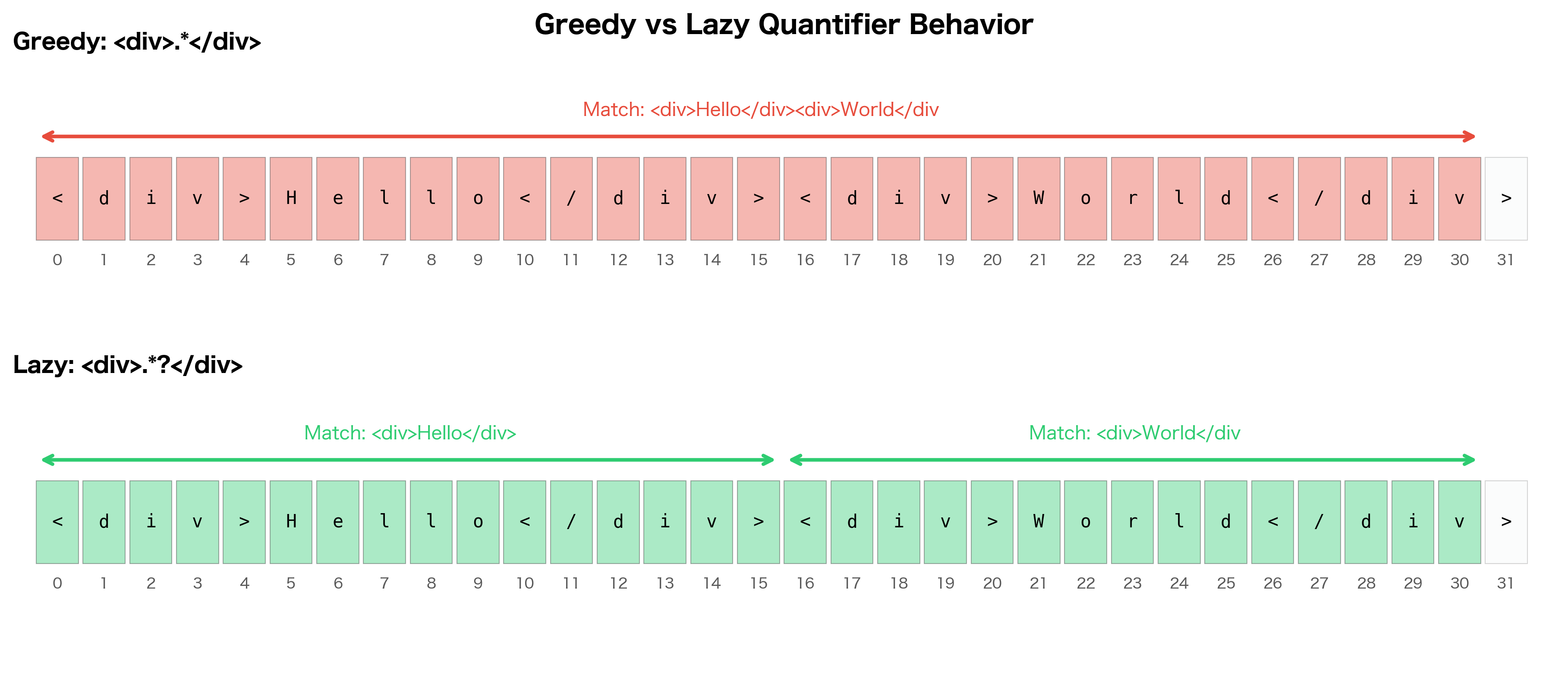

The greedy pattern matched from the first <div> all the way to the last </div>, consuming both tags. The lazy pattern stopped at the first </div> it found, giving us each tag separately. This distinction is critical when parsing structured text.

Anchors: Position Matching

Anchors match positions in the string rather than characters. Unlike metacharacters that consume text, anchors assert that the current position in the string meets certain criteria. This makes them essential for matching patterns at specific locations, such as the beginning of a line or at word boundaries.

Word boundaries are essential for matching whole words. The \b anchor matches the position between a word character and a non-word character. In "catalog", there's no word boundary before or after "cat", so \bcat\b doesn't match it.

Grouping and Capturing

Parentheses serve two purposes in regex: grouping elements together and capturing matched text for later use. Grouping lets you apply quantifiers to multi-character sequences or create alternations. Capturing stores the matched text so you can reference it later in the pattern or in replacement strings.

Basic Groups

When you use findall() with groups, it returns only the captured group contents, not the full match. This is often what you want when extracting specific parts of a pattern.

Multiple Groups

Named Groups

Named groups make patterns more readable and self-documenting:

Named groups are especially valuable in complex patterns where numbered groups become confusing.

Non-Capturing Groups

Sometimes you need grouping for structure but don't want to capture the content. Use (?:...):

Non-capturing groups keep your results clean when you only care about specific parts of the pattern.

Backreferences

Backreferences let you match the same text that was captured by an earlier group:

The \1 refers back to whatever was captured by the first group. In the repeated words example, if the first group captures "the", then \1 only matches another "the", not any word.

Lookahead and Lookbehind

Lookahead and lookbehind assertions match a position based on what comes before or after, without consuming any characters. These are called "zero-width assertions" because they check conditions without advancing the regex engine's position in the string. This makes them powerful for extracting text that appears in specific contexts while excluding the context itself from the match.

Lookahead

Lookbehind

Lookarounds are powerful for extracting data from structured formats where you want the context to guide matching but don't want the context in your result.

Flags and Modifiers

Regex flags modify how patterns are interpreted:

The re.VERBOSE flag is particularly valuable for complex patterns. It lets you break patterns across lines and add comments, making them maintainable.

Common NLP Patterns

Let's build patterns for text elements you'll frequently encounter in NLP work. Real-world text contains a mix of entities like emails, URLs, phone numbers, dates, and social media elements. Understanding how to extract these is fundamental to text preprocessing.

Consider this sample social media post containing multiple entity types:

The table below summarizes the extraction results. Notice how social media content tends to have many mentions and hashtags, while business communications include emails and phone numbers:

| Entity Type | Count | Example Matches |

|---|---|---|

| Emails | 2 | support@company.com, sales@example.org |

| URLs | 2 | https://example.com/product?id=123, http://blog.example.org |

| Mentions | 3 | @john_doe, @tech_news, @deals_daily |

| Hashtags | 4 | #SAVE20, #BlackFriday, #CyberMonday, #Shopping |

| Phone Numbers | 2 | (555) 123-4567, +1-800-555-0199 |

| Dates (ISO) | 1 | 2024-12-31 |

| Dates (US) | 1 | 01/15/2024 |

Let's examine each pattern in detail.

Email Addresses

URLs

Phone Numbers

Dates

Hashtags and Mentions

Substitution and Transformation

The re.sub() function replaces matches with new text. You can use backreferences in the replacement string.

Compiling Patterns

For patterns you use repeatedly, compile them for better performance:

Compiled patterns also store flags, making your code cleaner when the same flags apply everywhere.

Performance Considerations

Regex engines use backtracking to find matches, which can lead to catastrophic performance on certain patterns.

Catastrophic Backtracking

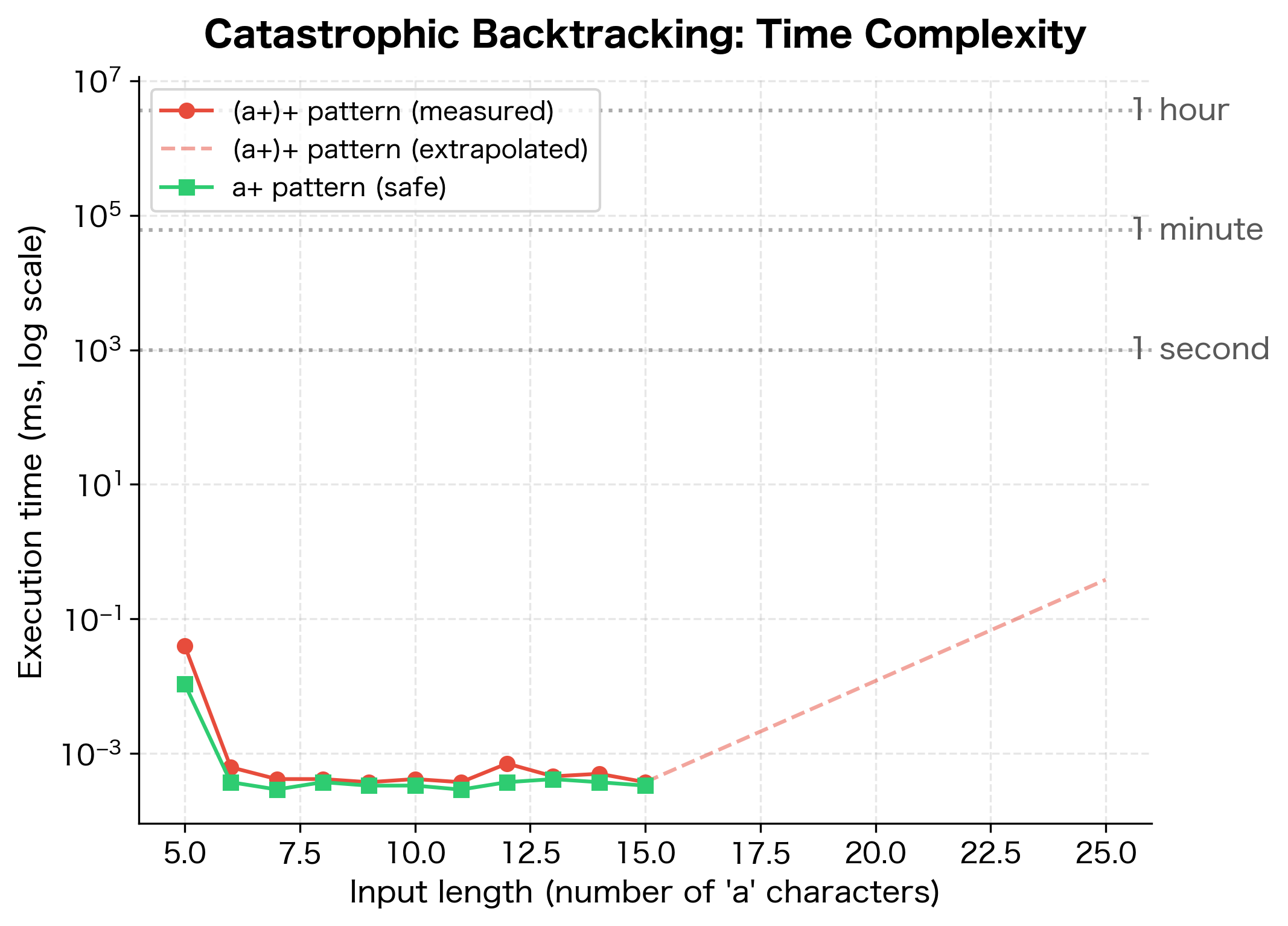

The exponential growth of backtracking time is one of the most important performance concepts to understand. Let's visualize how execution time explodes as input length increases:

The logarithmic scale reveals the exponential nature of the problem. While the safe pattern stays flat (constant time), the dangerous pattern's execution time doubles with each additional character. At 20 characters, matching takes seconds. At 25, it takes minutes. At 30, hours. This is why avoiding nested quantifiers is critical for production code.

Performance Tips

To write efficient regex patterns, follow these guidelines:

- Anchor when possible:

^patternis faster than searching the whole string - Be specific:

[0-9]is faster than\din some engines,[a-zA-Z]is faster than. - Avoid nested quantifiers:

(a+)+is dangerous; usea+instead - Use non-capturing groups:

(?:...)is slightly faster than(...) - Compile patterns: For repeated use,

re.compile()avoids re-parsing - Use possessive quantifiers or atomic groups: Python's

redoesn't support these, but theregexmodule does

Building a Text Cleaning Pipeline

Let's combine what we've learned into a practical text preprocessing pipeline:

When Not to Use Regex

Regex is powerful, but it's not always the right tool:

Don't use regex for:

- HTML/XML parsing: Use

BeautifulSouporlxml. Regex can't handle nested structures properly. - JSON/structured data: Use

jsonmodule. Regex is error-prone for complex formats. - Complex grammars: Use a proper parser (like

pyparsingorlark) for programming languages or complex formats. - Simple string operations:

str.split(),str.replace(),inoperator are clearer and faster for simple cases.

Limitations and Challenges

Regular expressions have fundamental limitations that you should understand before relying on them heavily:

- Context-free languages: Regex cannot match arbitrarily nested structures like balanced parentheses. No regex can match only strings with balanced parens like

((())). - Readability: Complex regex patterns become write-only code. The email pattern we used earlier is already hard to read, and production-grade patterns are worse.

- Maintenance: Small changes to requirements can require complete pattern rewrites. Adding "support international characters" to an email pattern is non-trivial.

- Unicode complexity: While Python's

remodule handles Unicode, character classes like\wmay not match all word characters in all languages. Theregexmodule with Unicode categories helps. - Performance unpredictability: Backtracking behavior makes it hard to predict execution time. A pattern that works fine on test data might hang on production data.

Key Functions and Parameters

When working with regular expressions in Python, these are the essential functions and their most important parameters:

re.search(pattern, string, flags=0)

pattern: The regex pattern to search forstring: The text to search withinflags: Optional modifiers likere.IGNORECASE,re.MULTILINE- Returns: A match object for the first match, or

Noneif no match

re.findall(pattern, string, flags=0)

- Returns all non-overlapping matches as a list of strings

- If the pattern has groups, returns a list of tuples containing the groups

re.finditer(pattern, string, flags=0)

- Returns an iterator of match objects for all matches

- Use when you need position information or access to groups

re.sub(pattern, repl, string, count=0, flags=0)

repl: Replacement string or functioncount: Maximum number of replacements (0 means all)- Backreferences like

\1can be used in the replacement string

re.split(pattern, string, maxsplit=0, flags=0)

maxsplit: Maximum number of splits (0 means no limit)- Returns a list of strings split at pattern matches

re.compile(pattern, flags=0)

- Pre-compiles a pattern for repeated use

- Returns a compiled pattern object with the same methods

Common Flags

re.IGNORECASE(orre.I): Case-insensitive matchingre.MULTILINE(orre.M):^and$match at line boundariesre.DOTALL(orre.S):.matches newlinesre.VERBOSE(orre.X): Allow comments and whitespace in patterns

Summary

Regular expressions provide a compact, powerful language for pattern matching in text. You've learned:

- Metacharacters:

.matches any character,[]defines character classes,^and$anchor to positions - Quantifiers:

*,+,?,{n,m}control repetition; add?for lazy matching - Groups:

()captures text,(?:)groups without capturing,(?P<name>)names captures - Lookarounds:

(?=),(?!),(?<=),(?<!)match positions based on context - Backreferences:

\1,\2refer back to captured groups - Flags:

re.IGNORECASE,re.MULTILINE,re.DOTALL,re.VERBOSEmodify behavior

Key practical patterns for NLP:

- Emails:

\b[A-Za-z0-9._%+-]+@[A-Za-z0-9.-]+\.[A-Z|a-z]{2,}\b - URLs:

https?://\S+ - Hashtags/Mentions:

#\w+,@\w+ - Word boundaries:

\bword\bfor whole-word matching

Best practices:

- Always use raw strings:

r"pattern" - Compile patterns used repeatedly

- Avoid nested quantifiers that cause catastrophic backtracking

- Use string methods for simple operations

- Use proper parsers for structured formats like HTML or JSON

In the next chapter, we'll explore sentence segmentation, where regex plays a supporting role in identifying sentence boundaries.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about regular expressions in Python.

Comments