Learn how n-gram language models assign probabilities to word sequences using the chain rule and Markov assumption, with implementations for text generation and scoring.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

N-gram Language Models

What makes some word sequences sound natural while others feel wrong? "The cat sat on the mat" flows effortlessly, but "mat the on sat cat the" is gibberish. Native speakers intuitively know which sequences are likely, even for sentences they've never encountered. N-gram language models capture this intuition mathematically, assigning probabilities to sequences of words based on patterns learned from text.

Language models are foundational to NLP. They power spell checkers that suggest "their" over "thier," autocomplete systems that predict your next word, and speech recognizers that disambiguate "recognize speech" from "wreck a nice beach." Before neural networks dominated the field, n-gram models were the workhorses of language modeling, and understanding them provides essential intuition for modern approaches.

This chapter builds n-gram language models from first principles. You'll learn the probability theory that makes them work, implement them from scratch, and discover both their power and fundamental limitations.

The Language Modeling Problem

A language model assigns probabilities to sequences of words. Given a sequence of words, denoted , the model estimates , the probability of that exact sequence occurring in natural language. Here represents the -th word in the sequence (e.g., might be "the" and might be "cat").

A language model is a probability distribution over sequences of words. It assigns higher probabilities to sequences that are more likely to occur in natural language and lower probabilities to unlikely or ungrammatical sequences.

Why is this useful? Consider a speech recognition system that hears an ambiguous audio signal. It might produce two candidate transcriptions: "I saw a van" and "eyes awe of an." A language model knows the first is far more probable and helps the system choose correctly.

Language models also enable text generation. If we can compute for any sequence, we can generate new text by sampling words according to their probabilities given the preceding context.

The Chain Rule of Probability

Computing the probability of a full sequence seems daunting at first. How could we possibly estimate directly? We'd need to count how often this exact six-word sequence appears in our training data, then divide by the total number of six-word sequences. But most sentences are unique. Even in a corpus of billions of words, we're unlikely to see any specific sentence more than a handful of times.

The chain rule of probability offers an escape from this dilemma. Instead of estimating the joint probability directly, we decompose it into a product of conditional probabilities. Each conditional asks a simpler question: given everything that came before, how likely is the next word?

The chain rule derives from the definition of conditional probability. Recall that conditional probability is defined as:

where:

- : the probability of event occurring given that event has already occurred

- : the joint probability of both and occurring together

- : the probability of event occurring (the denominator normalizes by the probability of the condition)

Rearranging, we get the multiplication rule: . This says the probability of both events equals the probability of the first event times the probability of the second event given the first. For a sequence of words, we apply this rule repeatedly to break down the joint probability into simpler conditional probabilities:

Step 1: Start with the joint probability of all words. This is what we ultimately want to compute:

Step 2: Apply the multiplication rule to separate the last word. We treat "all words up to " as event and " appears next" as event :

Step 3: Repeat for the remaining words, working backwards. Each application peels off one more word from the joint probability until we reach the first word:

We can write this more compactly using product notation:

where:

- : the -th word in the sequence (e.g., , )

- : the conditional probability of word given all preceding words (the "history")

- : the product operator, which multiplies all terms together

The intuition is straightforward: the probability of a sequence equals the probability of the first word, times the probability of the second word given the first, times the probability of the third word given the first two, and so on. Each step conditions on all previously observed words.

This decomposition is exact, not an approximation. The probability of any sequence equals the product of each word's probability given its entire preceding context.

Let's see this decomposition in action with a concrete example:

Each term in this product answers a progressively more specific question. The first asks: how likely is "the" to start a sentence? The second asks: given we started with "the," how likely is "cat" to follow? By the time we reach the final word, we're asking: given the entire context "the cat sat on the," how likely is "mat"?

The chain rule is mathematically exact, but it creates a severe practical problem. To compute , we need the probability of word given the entire preceding context. For long sentences, this context can be arbitrarily long. A 20-word sentence requires us to estimate the probability of the 20th word given all 19 preceding words. We'll never have enough data to estimate these long-context probabilities reliably, since most 19-word contexts appear only once, if ever.

This is where the Markov assumption comes to the rescue.

The Markov Assumption

The chain rule gives us an exact decomposition, but it demands something impossible: reliable estimates of probabilities conditioned on arbitrarily long histories. The key insight of n-gram models is to make a simplifying assumption that trades some accuracy for tractability.

The Markov assumption states that the probability of a word depends only on a fixed-length history of preceding words, not the entire sequence. An n-gram model assumes the probability of word depends only on the previous words.

The assumption is named after the Russian mathematician Andrey Markov, who studied stochastic processes with this "memoryless" property. In the context of language, it means we pretend the future depends only on the recent past, not the distant past.

For a bigram model (), each word depends only on the single word immediately before it:

where:

- : the true conditional probability given the full history (left side)

- : the bigram approximation using only the immediately preceding word (right side)

- : indicates this is an approximation, not an equality

For a trigram model (), the memory extends to two previous words:

where:

- : the word two positions before the current word

- : the word immediately before the current word

- The context forms a two-word history

In general, for an n-gram model, we approximate:

where the context window spans exactly preceding words. The approximation symbol reminds us this is a simplification: we're discarding information from the distant past to make estimation tractable.

Why does this help? Consider the difference in what we need to estimate:

- Full history: We need , requiring counts of the specific five-word context "the cat sat on the"

- Trigram: We need , requiring only counts of the two-word context "on the"

- Bigram: We need , requiring only counts of the single word "the"

Shorter contexts appear far more frequently in training data, giving us more reliable probability estimates.

Is the Markov assumption reasonable? Strictly speaking, no. The probability of "mat" after "the cat sat on the" depends on "cat" and "sat," which establish that we're talking about an animal sitting somewhere. A bigram model, seeing only "the," has no idea whether we're discussing cats on mats, birds in trees, or books on shelves.

Yet this approximation works well in practice, especially for larger values of . Language has enough local structure that nearby words carry most of the predictive information. The word "on" strongly predicts a location or surface will follow. The phrase "sat on" even more strongly suggests something like "mat," "chair," or "floor." We lose some information, but we gain the ability to estimate probabilities reliably.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation

With the Markov assumption in hand, we've reduced our problem to estimating conditional probabilities like . But how do we actually compute these from data?

The most straightforward approach is maximum likelihood estimation (MLE): count how often each n-gram appears in our training corpus, then normalize. The intuition comes from the definition of conditional probability:

where:

- : the probability of given

- : the joint probability of both events occurring

- : the probability of the conditioning event

For language, this translates to: the probability of word following context equals the fraction of times we observed followed by , out of all the times we observed .

For bigrams, the MLE estimate is:

where:

- : the count of times the bigram appears consecutively in the training corpus

- : the count of times the context word appears (in any context)

- The ratio gives the proportion of occurrences that are followed by

Example: If "the" appears 100 times in our corpus, and "the cat" appears 8 times, then:

This means 8% of the time "the" is followed by "cat."

For trigrams, we extend the same logic to two-word contexts:

where:

- : the count of the trigram (three consecutive words)

- : the count of the bigram context (the first two words of the trigram)

The general pattern for any n-gram order is:

where:

- : the word whose probability we want to estimate

- : the context of words immediately preceding

- : the count of the complete n-gram (context plus target word) in the training corpus

- : the count of the context alone (how often this -gram appears)

The formula always divides the count of the full n-gram by the count of its -gram prefix (the context). This relative frequency estimate is the maximum likelihood solution because it maximizes the probability of observing the training data under the model.

Let's implement this and see it work on a small corpus:

Our small corpus contains 24 tokens but only 9 unique words. The most frequent bigrams are ("the", "cat") and ("the", "dog"), each appearing twice. Notice how "the" dominates as the first element of many bigrams, reflecting its role as the most common English word.

| Word | Count |

|---|---|

| the | 8 |

| cat | 3 |

| dog | 2 |

| sat | 2 |

| on | 2 |

| mat | 2 |

| chased | 1 |

| ate | 1 |

| fish | 1 |

| Bigram | Count |

|---|---|

| the → cat | 2 |

| the → dog | 2 |

| the → mat | 2 |

| on → the | 2 |

| sat → on | 2 |

| cat → sat | 1 |

| cat → ate | 1 |

| ate → the | 1 |

| the → fish | 1 |

| dog → sat | 1 |

| dog → chased | 1 |

| chased → the | 1 |

The frequency distributions reveal a pattern common to all natural language: a few items dominate while most appear rarely. "The" appears 8 times, more than any other word, while most bigrams appear only once. This Zipf-like distribution explains why n-gram models struggle with data sparsity. As we move to higher-order n-grams, the long tail grows longer, and most n-grams remain unseen even in large corpora.

Now let's apply the MLE formula to compute actual probabilities:

The probabilities reveal patterns in our corpus. After "the," both "cat" and "dog" appear with equal probability (25% each), while "mat" also appears 25% of the time. After "sat," the word "on" appears with 100% probability, reflecting the fixed phrase "sat on" that appears in every relevant sentence. After "on," the word "the" follows every time, since our corpus always uses "on the" before the final noun.

These probabilities capture the local structure of our tiny corpus. A model trained on this data would predict that "sat" is always followed by "on," and "on" is always followed by "the." Of course, with only four sentences, these patterns are artifacts of our limited data. A larger corpus would reveal more nuanced distributions.

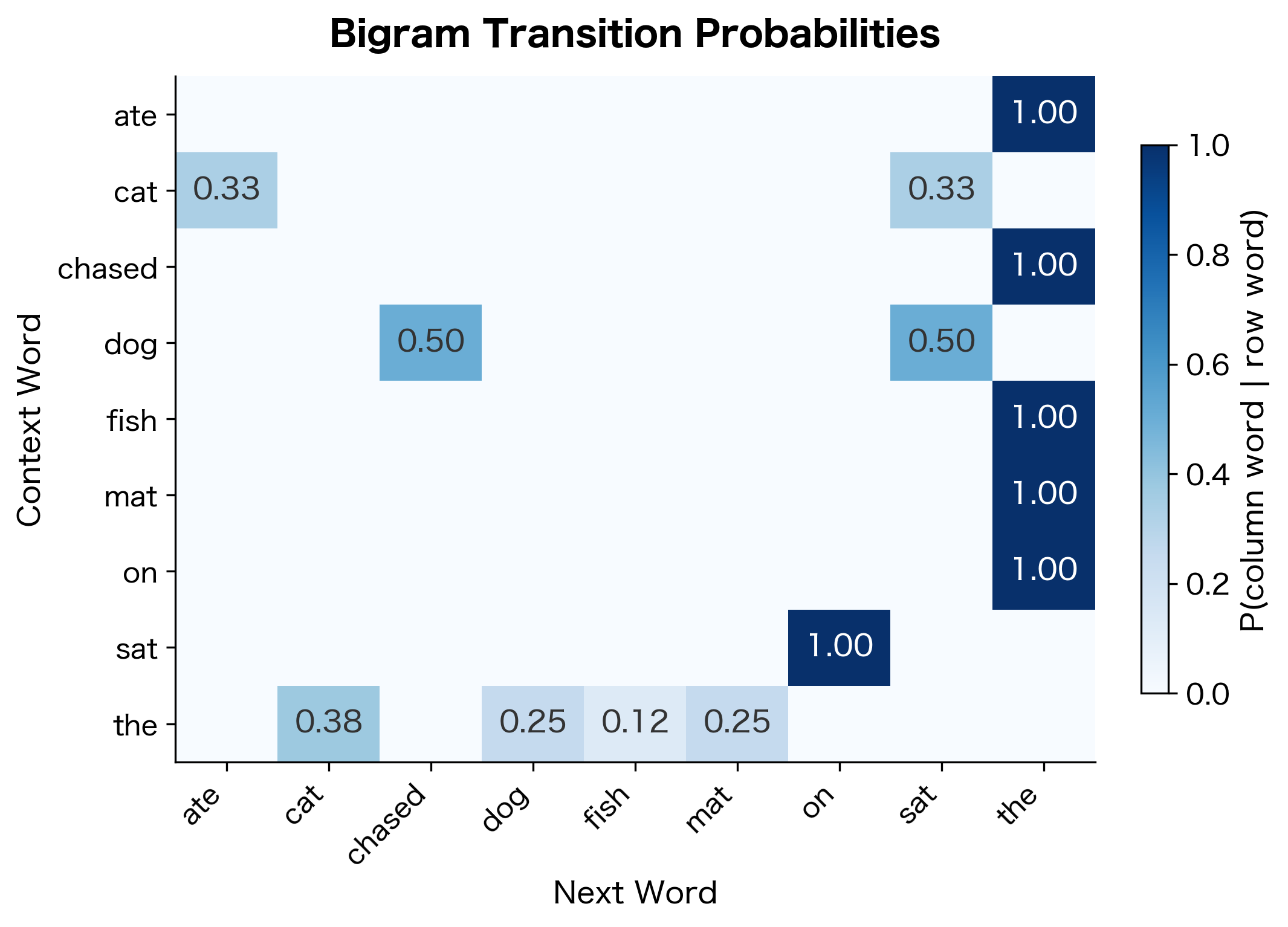

We can visualize the complete bigram probability matrix as a heatmap, where each cell shows , the probability of word following word :

The heatmap reveals the sparse structure of bigram probabilities. Most cells are empty (zero probability), indicating word pairs that never occurred in our corpus. The non-zero cells cluster around specific patterns: "the" can be followed by several words, but "sat" is always followed by "on." This sparsity becomes even more pronounced with larger vocabularies and higher-order n-grams.

Start and End Tokens

Sentences have beginnings and endings. To model this, we add special tokens: <s> marks the start of a sentence and </s> marks the end. These tokens let us model which words typically start sentences and which words end them.

The start marker <s> lets us compute , the probability of a word starting a sentence. In our corpus, "the" starts every sentence, so . The end marker </s> lets us model sentence endings: "mat," "fish," and "cat" all end sentences.

For higher-order n-grams, we add multiple start tokens. A trigram model needs two <s> tokens at the beginning to provide context for the first two words.

Computing Sequence Probabilities

With n-gram probabilities estimated, we can compute the probability of any sequence. We combine the chain rule decomposition with our Markov approximation to get:

where:

- : the total number of words in the sequence

- : the n-gram order (e.g., 2 for bigrams, 3 for trigrams)

- : the -th word in the sequence

- : the context of words immediately preceding

- : multiply together all conditional probabilities

For a bigram model (), this simplifies to:

where:

- : the probability of the first word given the start-of-sentence marker

- : the probability of word given only the single preceding word

- The product includes terms for a sentence of words (plus the end token if we include it)

Each term uses only the single preceding word as context. For the first word in the sequence, we use the start token <s> to provide the required context. This ensures every word has a well-defined conditioning context, even at sentence boundaries.

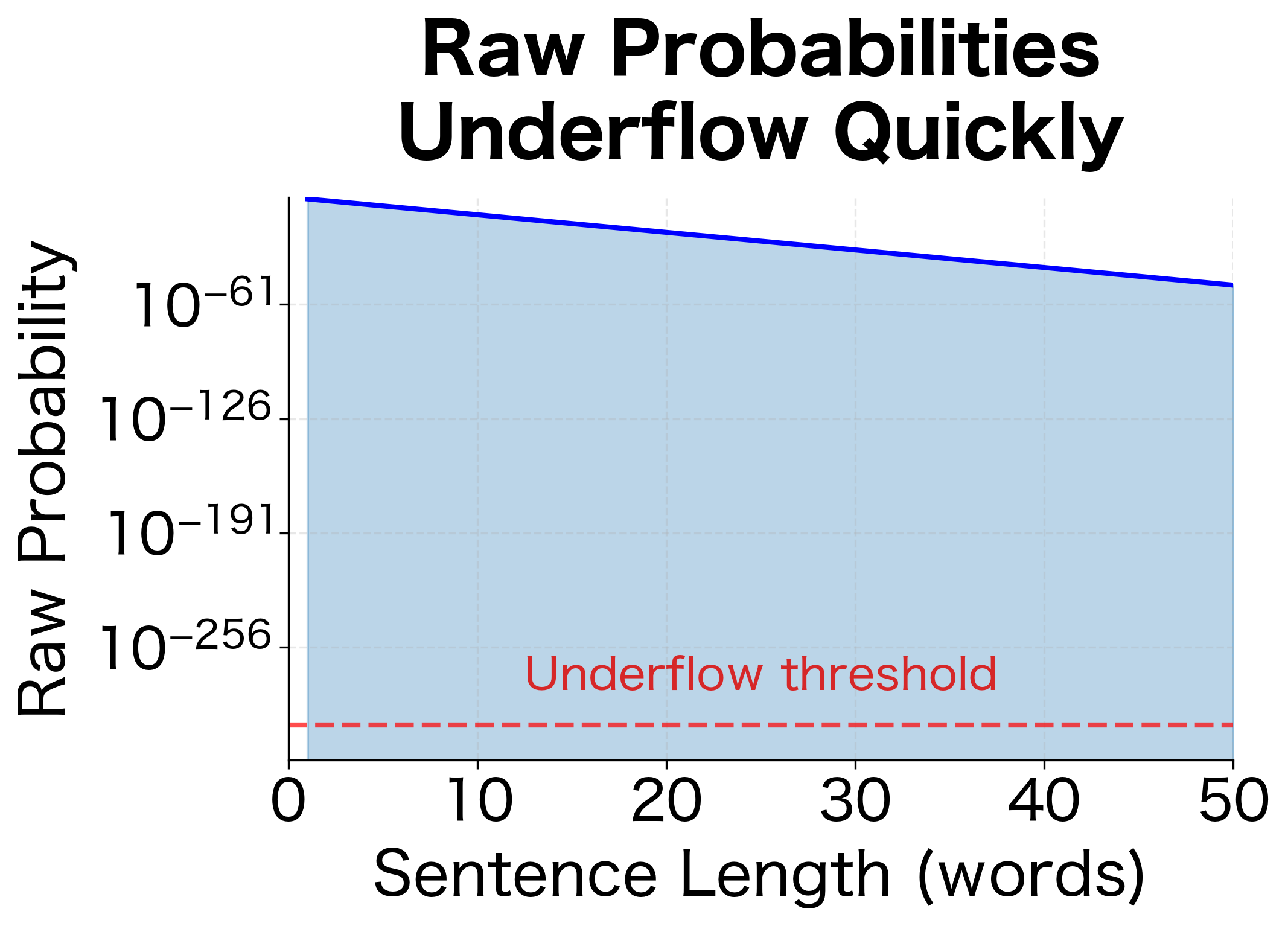

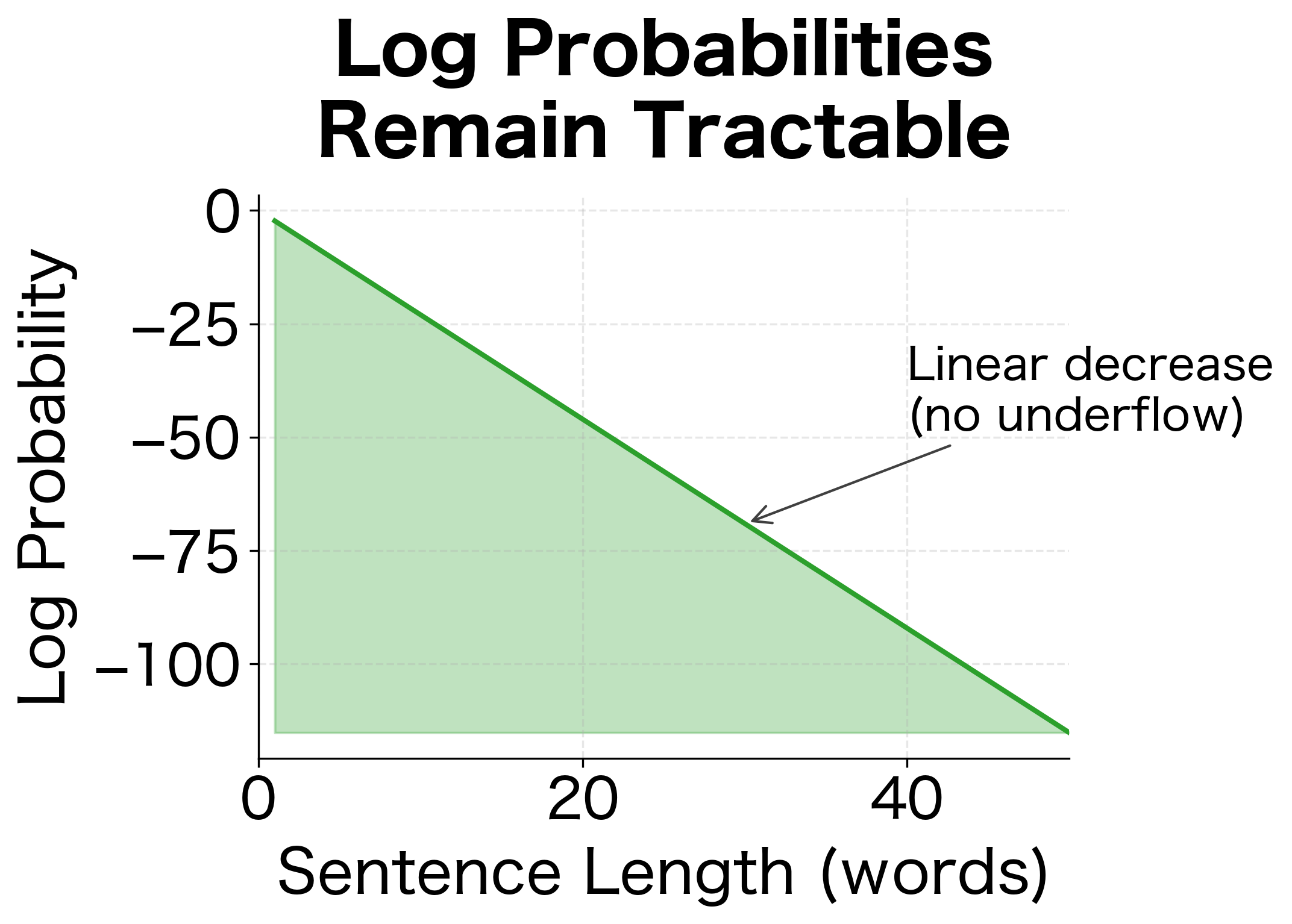

Notice we use log probabilities. Multiplying many small probabilities leads to numerical underflow, where numbers become too small to represent in floating-point arithmetic. Taking logarithms converts products to sums, keeping values in a manageable range.

The mathematical transformation works as follows. Instead of computing a product of probabilities (which can underflow):

we compute a sum of log probabilities (which remains numerically stable):

where:

- : the natural logarithm function (base )

- : sum over all words in the sequence

- : the log probability of each bigram conditional (always negative since )

- The result is the log of the original sequence probability

This transformation works because of the logarithm's fundamental property: . The log of a product equals the sum of the logs. While individual probabilities might be 0.01 or smaller, their log values are manageable negative numbers (e.g., ). Summing these values is numerically stable even for very long sequences. To recover the original probability if needed, we compute .

The visualization shows why log probabilities are essential. With an average per-word probability of 0.1, raw probabilities become vanishingly small after about 30 words, approaching the limits of floating-point representation. Log probabilities decrease linearly and remain computationally tractable for sentences of any length.

The rankings reveal what our model learned. Sentences similar to the training data ("the cat sat on the mat") get higher probabilities. Sentences with unseen bigrams ("the fish ate") may get zero probability, resulting in negative infinity log probability.

The Zero Probability Problem

What happens when we encounter an n-gram that never appeared in training?

A single unseen bigram makes the entire sequence probability zero. This is a serious problem: perfectly valid sentences get zero probability just because our training data didn't contain every possible word combination.

This is the zero probability problem. It motivates the smoothing techniques covered in the next chapter. Raw MLE estimates are too brittle for real applications.

Building a Complete N-gram Model

Let's build a complete, reusable n-gram language model class:

The NgramLanguageModel class encapsulates all the logic we've built: n-gram counting, context tracking, and probability computation. The train() method processes text and builds the count tables. The probability() method returns using MLE, and sentence_log_probability() computes the log probability of an entire sentence.

Let's train models of different orders and compare them:

The results reveal key differences between model orders. The unigram model assigns similar probabilities to all sentences because it ignores word order entirely, treating each word independently. The bigram model shows more variation, penalizing sentences with rare or unseen word transitions. The trigram model provides the finest discrimination, since it captures two-word context patterns.

Notice that some sentences receive -inf (negative infinity) log probability when they contain unseen n-grams. The sentence "the cat ate the bird" might score well with lower-order models but fail with the trigram if the specific three-word sequence never appeared in training. This illustrates the data sparsity problem: higher-order models are more expressive but require more training data.

Generating Text from N-gram Models

N-gram models can generate new text by sampling words according to their conditional probabilities. Starting from the start token, we repeatedly sample the next word given the current context.

The bigram model generates sentences that reflect local word patterns from the training data. Each transition depends only on the immediately preceding word, so the model can produce grammatically plausible fragments but may lose coherence over longer spans. Notice how sentences often loop back to common patterns like "the cat" or "the dog."

Now let's generate with the trigram model, which uses two words of context:

The generated text reflects patterns in the training data. Bigram models produce locally coherent text but may wander incoherently over longer spans. Trigram models maintain coherence over slightly longer distances, but neither captures long-range dependencies like subject-verb agreement across clauses.

Temperature Sampling

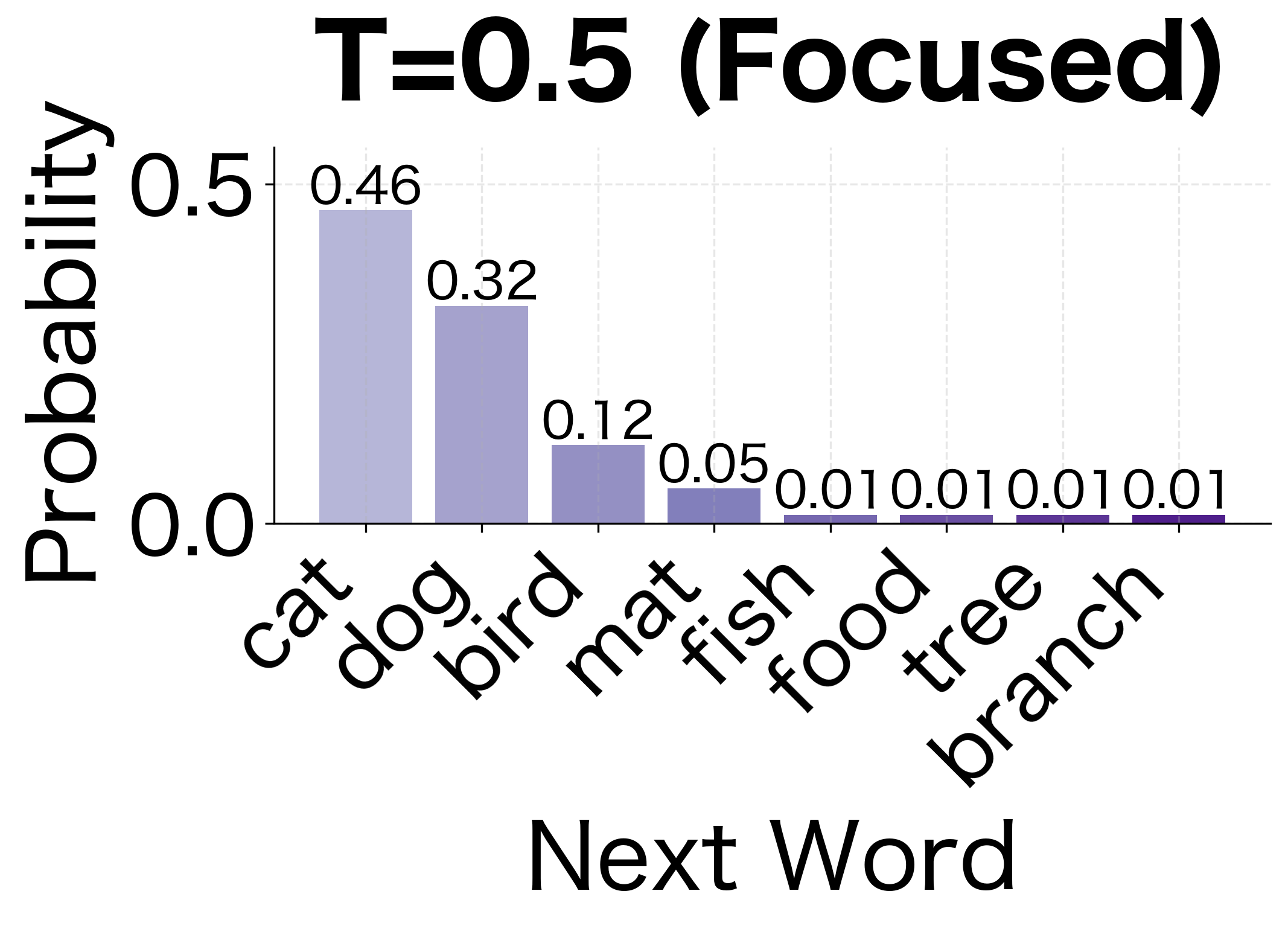

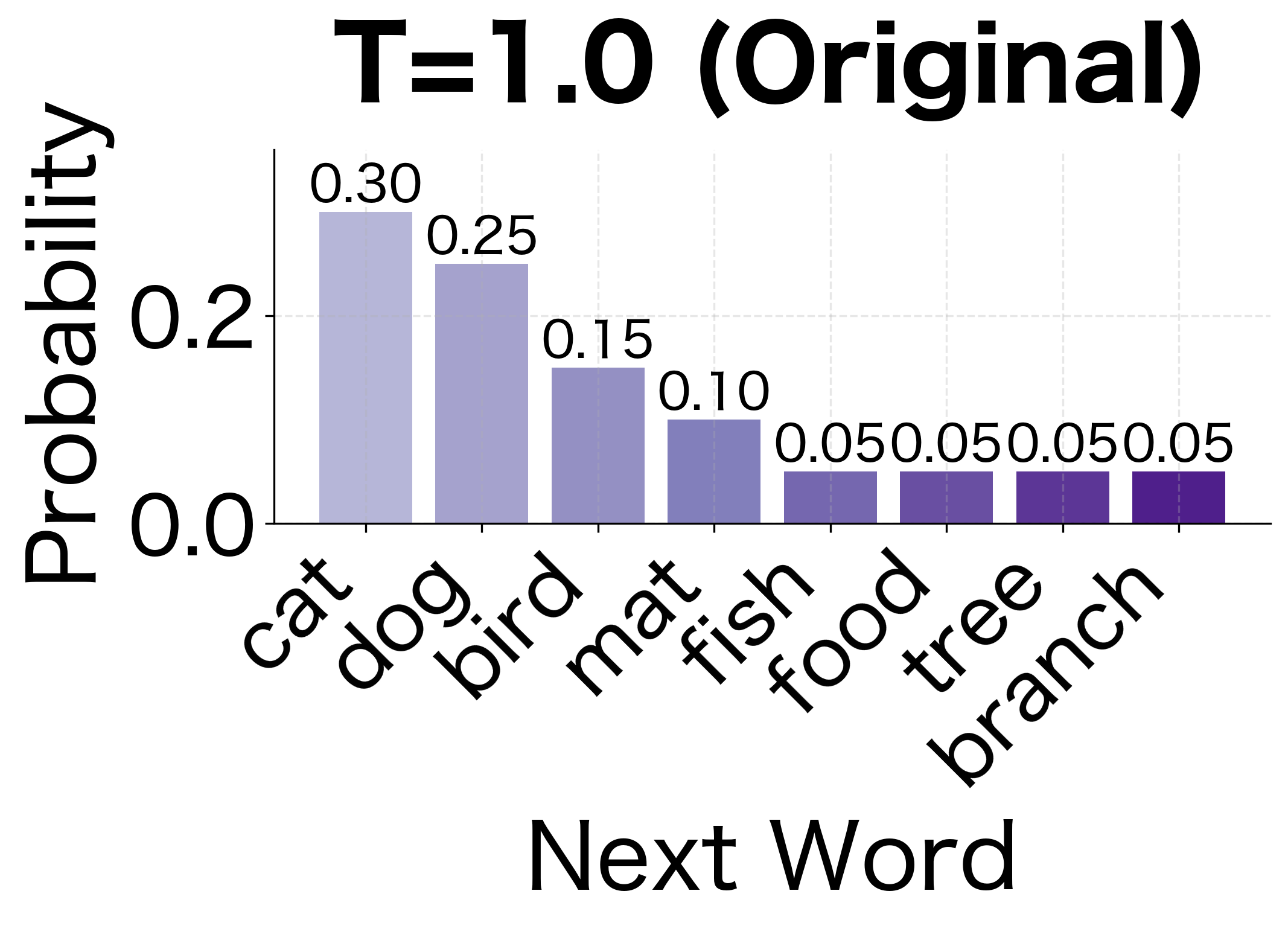

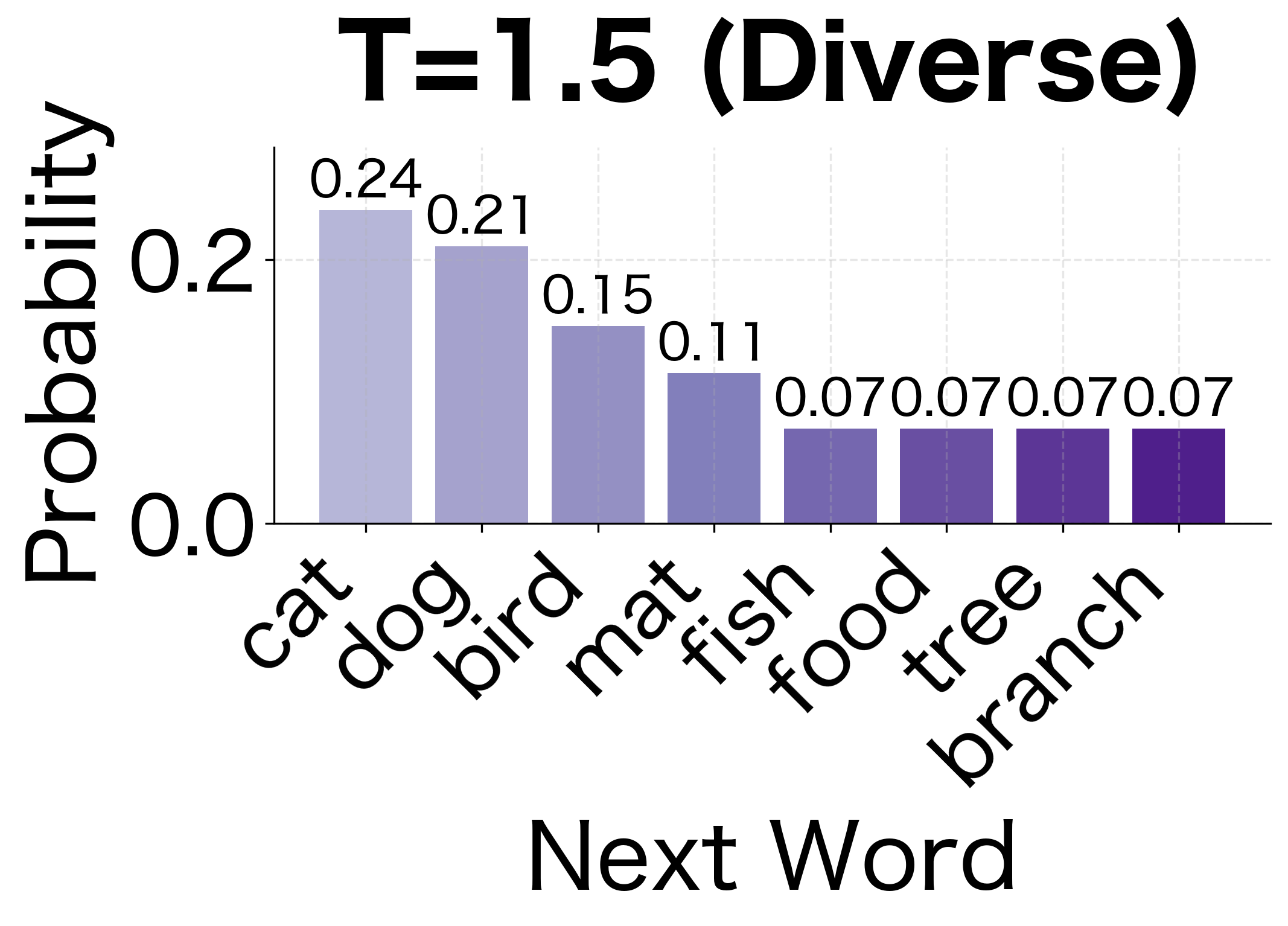

We can control the randomness of generation with a temperature parameter . Given a probability distribution over next words, temperature scaling adjusts the distribution's "sharpness" before sampling.

The idea is to divide the log probabilities by before re-normalizing. Since log probabilities are negative (probabilities are less than 1), dividing by a small amplifies the differences between them. For example, if and , dividing by gives and , doubling the gap. Conversely, dividing by a large shrinks differences, making the distribution more uniform.

where:

- : the original probability of word from the language model

- : the temperature parameter (a positive real number, typically between 0.1 and 2.0)

- : the temperature-adjusted probability used for sampling

- : the exponential function, which converts log probabilities back to probabilities

- : the scaled log probability (dividing by controls how much we amplify or compress differences)

- : the normalization constant, ensuring probabilities sum to 1

The temperature controls how "peaked" or "flat" the distribution becomes:

- (low temperature): Dividing log probabilities by a small number makes differences larger, sharpening the distribution and concentrating probability on the most likely words

- : Uses the original probabilities unchanged

- (high temperature): Dividing by a large number shrinks differences, flattening the distribution and giving rare words more chance of being selected

Lower temperatures make the model more deterministic, always choosing high-probability words. Higher temperatures increase diversity:

At low temperatures, the model gravitates toward the most common patterns. At high temperatures, it explores less likely paths and sometimes produces more creative but less coherent output.

The visualization shows how temperature reshapes probability distributions. At low temperature (0.5), the highest-probability words become even more dominant, making generation more predictable. At high temperature (1.5), the distribution flattens, giving rare words a fighting chance. This trade-off between coherence and diversity is fundamental to text generation with language models.

Model Storage and Efficiency

N-gram models can grow large. The number of possible n-grams grows exponentially with . Given a vocabulary of unique words, the total number of possible n-grams is:

where:

- : the vocabulary size (number of unique words)

- : the n-gram order

- : multiplied by itself times (exponential growth)

This exponential growth creates a storage challenge. For English with words and (trigrams), we have potential trigrams. Even storing just one byte per trigram would require a petabyte of memory. Fortunately, most of these combinations never occur in real text.

Sparse Storage

Most possible n-grams never occur. We store only observed n-grams using dictionaries or hash tables:

The trigram model stores more n-grams than the bigram model because it tracks longer sequences. Our toy corpus produces tiny models measured in kilobytes, but real-world models trained on billions of words can require gigabytes of storage. This makes efficient data structures essential.

Trie-Based Storage

For faster lookups, n-grams can be stored in a trie (prefix tree). Each path from root to node represents an n-gram prefix. Nodes store counts:

The trie efficiently retrieves counts for any prefix. Notice how "the" has a high count because it appears in every sentence, while longer n-grams like "the cat sat" are less frequent. Tries share prefixes between n-grams, reducing memory for models with many overlapping contexts. They also enable efficient prefix queries like "What words can follow 'the cat'?"

Visualizing N-gram Distributions

How do n-gram probabilities distribute across possible continuations? The following tables show how different contexts constrain the next word:

| Next Word | P(word | "the") |

|---|---|

| cat | 0.20 |

| dog | 0.20 |

| mat | 0.20 |

| bird | 0.10 |

| fish | 0.10 |

| food | 0.05 |

| tree | 0.05 |

| branch | 0.05 |

| Next Word | P(word | "sat") |

|---|---|

| on | 1.00 |

| Next Word | P(word | "the cat") |

|---|---|

| sat | 0.25 |

| ate | 0.25 |

| ran | 0.25 |

| watched | 0.25 |

The distributions reveal how context constrains possibilities. After "the," many words are plausible, but after "sat," almost all probability mass concentrates on "on." Longer contexts generally produce more peaked distributions, reflecting stronger constraints.

Working with NLTK

NLTK provides built-in n-gram functionality:

The NLTK predictions match what we'd expect from our training data. Given the context "the," the model predicts words like "cat," "dog," and "bird" that frequently follow "the" in the corpus. Given "sat on," the model strongly predicts "the" since that's the only continuation seen in training.

NLTK's language modeling module handles the bookkeeping of n-gram counting, vocabulary management, and probability computation. This lets you focus on higher-level tasks rather than reimplementing the fundamentals.

Limitations of N-gram Models

N-gram models have served NLP well, but they face fundamental limitations:

- Limited context: The Markov assumption ignores long-range dependencies. In "The cat that the dog chased ran away," the verb "ran" agrees with "cat," but a trigram model only sees "chased ran away."

- Data sparsity: Most possible n-grams never occur in training data. Even with billions of words, many valid word combinations remain unseen.

- No generalization: N-gram models can't recognize that "the cat sat" and "the dog sat" share similar structure. Each n-gram is treated independently.

- Storage requirements: Large vocabularies and high-order n-grams require substantial memory. A trigram model for a 100,000-word vocabulary could theoretically have parameters.

- No semantic understanding: The model doesn't know that "cat" and "feline" are related, or that "bank" has multiple meanings.

The following table quantifies the data sparsity problem. As n-gram order increases, the percentage of test n-grams seen during training drops dramatically:

| N-gram Order | Model Type | Test Coverage | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Unigram | 98% | Almost all words seen in training |

| 2 | Bigram | 85% | Most word pairs covered |

| 3 | Trigram | 62% | Significant gaps emerge |

| 4 | 4-gram | 35% | Majority unseen |

| 5 | 5-gram | 15% | Severe sparsity; most test sequences never occurred in training |

Despite these limitations, n-gram models remain useful. They're fast, interpretable, and work well for many applications. They also provide the conceptual foundation for understanding more sophisticated models.

What N-gram Models Unlocked

Before neural language models, n-grams powered critical applications:

- Speech recognition: N-gram language models helped disambiguate acoustically similar phrases and improved recognition accuracy.

- Machine translation: Statistical MT systems used n-gram models to score translation fluency, preferring outputs that sounded natural.

- Spelling correction: N-gram probabilities identify which corrections produce more likely word sequences.

- Text prediction: Early autocomplete systems used n-grams to suggest likely next words.

- Information retrieval: N-gram statistics help identify important phrases and improve search ranking.

The concepts introduced by n-gram models remain central to modern language modeling: conditional probability, the chain rule, and the trade-off between context length and data sparsity. Transformers and large language models are sophisticated solutions to the problems n-gram models first revealed.

Key Parameters

When building n-gram language models, several parameters affect model behavior and performance.

n (n-gram order)

The order determines how many words of context the model considers. Common choices:

n=1(unigram): No context, just word frequencies. Fast but ignores word order entirely.n=2(bigram): One word of context. Good balance of simplicity and performance for many tasks.n=3(trigram): Two words of context. Standard choice for production systems before neural models.n=4or higher: Rarely used due to severe data sparsity. Requires massive training corpora.

Higher values capture more context but exponentially increase the number of possible n-grams. This leads to sparse counts and zero probabilities for valid sequences.

temperature (for generation)

Controls randomness during text generation:

temperature < 1.0: More deterministic, favors high-probability words. Use for predictable, conservative output.temperature = 1.0: Samples according to true model probabilities. Balanced creativity and coherence.temperature > 1.0: More random, explores low-probability words. Use for creative, diverse output at the cost of coherence.

Values between 0.7 and 1.2 work well for most applications.

Start and end tokens

Special tokens mark sentence boundaries:

<s>: Marks sentence beginnings. Addn-1copies for an n-gram model to provide context for the first words.</s>: Marks sentence endings. Enables the model to learn which words typically end sentences.

Vocabulary handling

Several preprocessing choices affect vocabulary size and model coverage:

- Case normalization: Converting to lowercase reduces vocabulary size but loses information (e.g., "Apple" vs "apple").

- Unknown token

<UNK>: Replacing rare words with a special token handles out-of-vocabulary words during inference. - Minimum frequency threshold: Excluding words that appear fewer than k times reduces noise from typos and rare terms.

Summary

N-gram language models assign probabilities to word sequences by decomposing joint probabilities into conditional probabilities using the chain rule. The Markov assumption limits context to the previous words, making estimation tractable.

Key takeaways:

- Chain rule decomposition breaks sequence probability into a product of conditional probabilities

- Markov assumption limits history to words, trading accuracy for tractability

- Maximum likelihood estimation computes probabilities as normalized n-gram counts

- Start and end tokens model sentence boundaries explicitly

- Log probabilities prevent numerical underflow when multiplying many small values

- Zero probability problem occurs when test data contains unseen n-grams

- Text generation samples words according to conditional probabilities

- Storage efficiency requires sparse data structures like tries

N-gram models reveal the fundamental tension in language modeling: longer context improves predictions but requires exponentially more data. This insight motivates both smoothing techniques, covered next, and the neural approaches that eventually superseded n-gram models.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about n-gram language models.

Comments