Master character encoding fundamentals including ASCII, Unicode, and UTF-8. Learn to detect, fix, and prevent encoding errors like mojibake in your NLP pipelines.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Character Encoding

Before computers can process language, they must solve a fundamental problem: how do you represent human writing as numbers? Every letter, symbol, and emoji you see on screen is stored as a sequence of bytes. Character encoding is the system that maps between human-readable text and these numerical representations. Understanding encoding is essential for NLP practitioners because encoding errors corrupt your data silently, turning meaningful text into unintelligible garbage.

This chapter traces the evolution from ASCII's humble 7-bit origins through Unicode's ambitious goal of representing every writing system, and finally to UTF-8, the encoding that now dominates the web. You'll learn why encoding matters, how to detect and fix encoding problems, and how to handle text correctly in Python.

The Birth of ASCII

In the early days of computing, there was no universal standard for representing text. Different manufacturers used different codes, making data exchange between systems nearly impossible. In 1963, the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) emerged as a solution to this chaos.

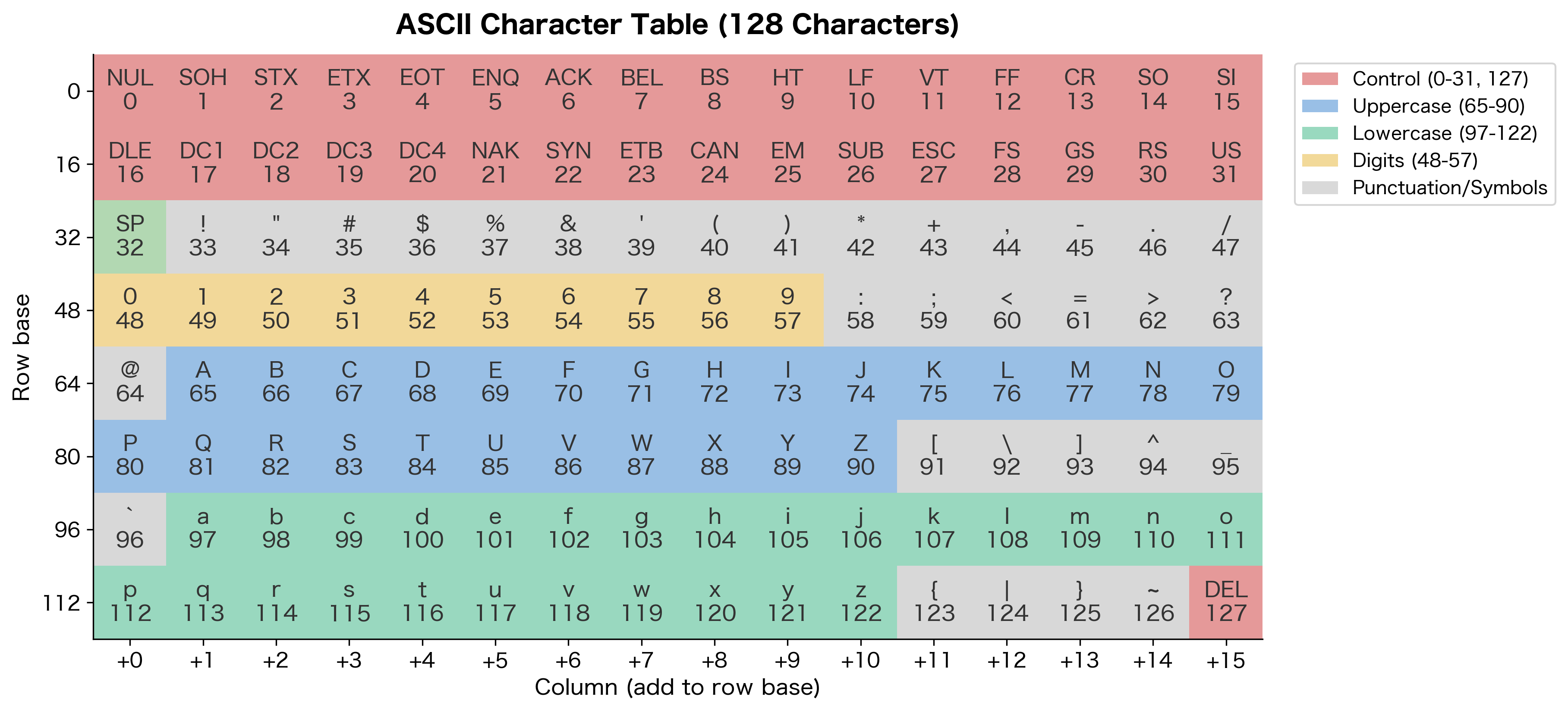

ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) is a character encoding standard that uses 7 bits to represent 128 characters, including uppercase and lowercase English letters, digits, punctuation marks, and control characters.

ASCII uses 7 bits per character, allowing for possible values (0 through 127). The designers made clever choices about how to organize these 128 slots:

- Control characters (0-31, 127): Non-printable characters for device control, like newline, tab, and carriage return

- Printable characters (32-126): Space, digits, punctuation, uppercase letters, and lowercase letters

Let's explore the ASCII table in Python:

The 33 control characters handle non-printable operations like line breaks and tabs. The remaining 95 printable characters cover everything needed for basic English text.

Notice something elegant: uppercase 'A' is 65, and lowercase 'a' is 97, exactly 32 positions apart. Since , this difference corresponds to a single bit position in binary. The designers ensured that converting between cases requires only flipping bit 5. This made case conversion trivially efficient on early hardware.

This bit-flipping trick extends to all 26 letters. To convert any uppercase letter to lowercase, you simply set bit 5 to 1 (add 32). To convert lowercase to uppercase, clear bit 5 (subtract 32).

The 7-Bit Limitation

ASCII's 7-bit design was both its strength and its fatal flaw. Using only 7 bits meant that ASCII fit comfortably within an 8-bit byte, leaving one bit free for error checking (parity) during transmission over unreliable communication lines. This was critical in an era of noisy telephone connections.

But 128 characters could only represent English. What about French accents? German umlauts? Greek letters? Russian Cyrillic? Chinese characters? ASCII had no answer.

An 8-bit byte can represent values, but ASCII only uses the first 128 (0-127). The remaining 128 values (128-255) became a battleground. Different regions created their own "extended ASCII" standards:

- ISO-8859-1 (Latin-1): Western European languages

- ISO-8859-5: Cyrillic alphabets

- Windows-1252: Microsoft's variant of Latin-1

- Shift JIS: Japanese

- GB2312: Simplified Chinese

This fragmentation created a nightmare. A document written on a French computer might display as garbage on a Greek computer. The same byte sequence meant different things depending on which encoding you assumed.

This is why encoding matters for NLP. If you don't know the encoding of your text data, you might be training your model on corrupted garbage.

Unicode: One Code to Rule Them All

By the late 1980s, the encoding chaos had become untenable. Software companies were spending enormous effort handling multiple encodings, and data exchange remained problematic. The Unicode Consortium was incorporated in 1991, building on work that began in the late 1980s, with an ambitious goal: create a single character set that could represent every writing system ever used by humanity.

Unicode is a universal character encoding standard that assigns a unique number (called a code point) to every character across all writing systems, symbols, and emoji. It currently defines over 149,000 characters covering 161 scripts.

Unicode assigns each character a unique code point, written as U+ followed by a hexadecimal number. For example:

- U+0041 is 'A'

- U+03B1 is 'α' (Greek alpha)

- U+4E2D is '中' (Chinese character for "middle")

- U+1F600 is '😀' (grinning face emoji)

The code points span a vast range. Basic Latin characters like 'A' occupy low values (under 128), while the emoji sits at over 128,000, far beyond what a single byte could represent.

Unicode Planes

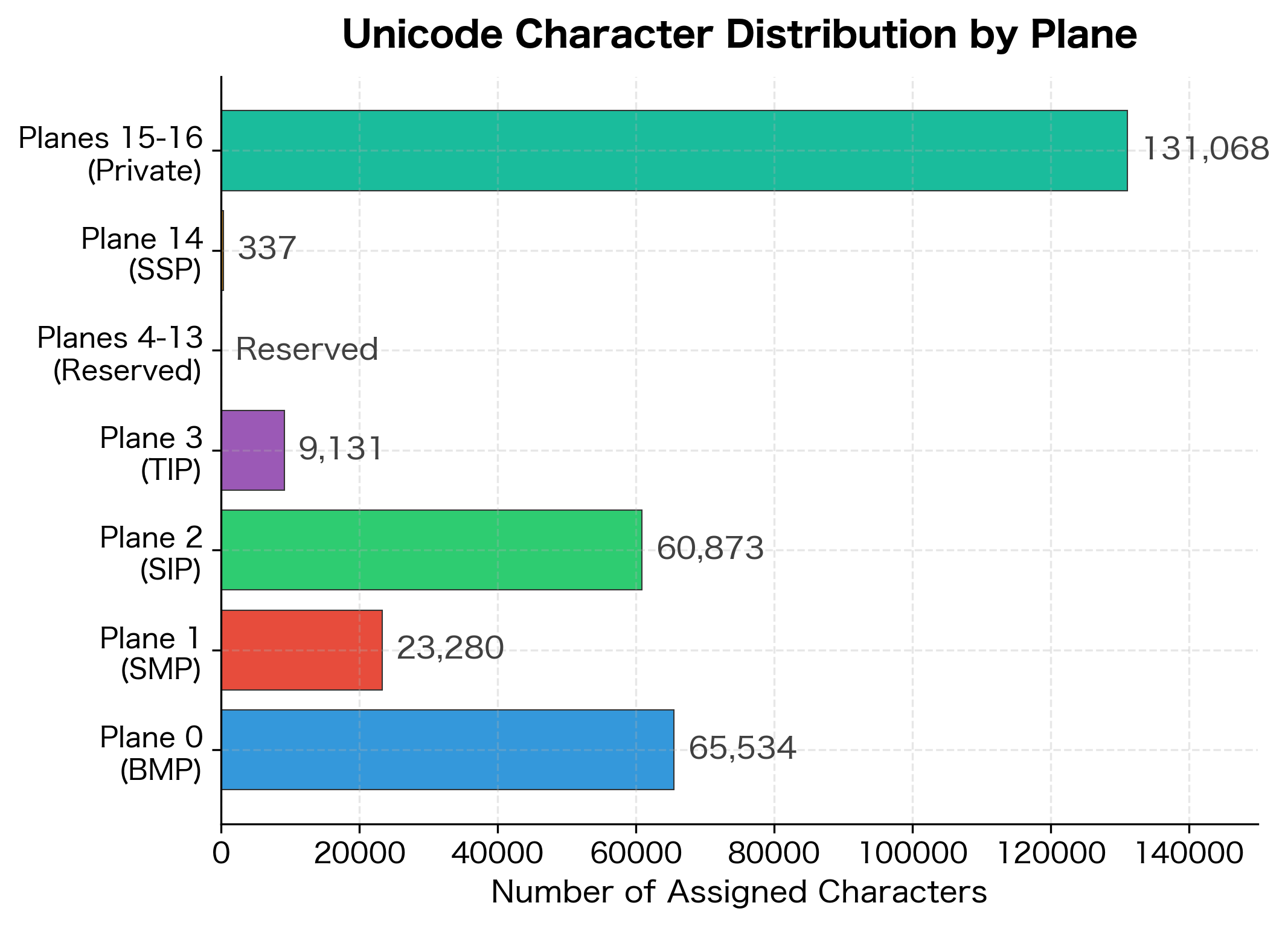

Unicode organizes its vast character space into 17 planes, each containing 65,536 code points (). The first plane is by far the most important:

- Plane 0 (Basic Multilingual Plane, BMP): U+0000 to U+FFFF. Contains characters for almost all modern languages, common symbols, and punctuation.

- Plane 1 (Supplementary Multilingual Plane): U+10000 to U+1FFFF. Historic scripts, musical notation, mathematical symbols, and emoji.

- Plane 2 (Supplementary Ideographic Plane): U+20000 to U+2FFFF. Rare CJK characters.

- Planes 3-13: Reserved for future use.

- Planes 14-16: Special purpose and private use.

For most NLP work, you'll primarily encounter characters in the BMP. However, emoji (increasingly common in social media text) and certain mathematical symbols live in Plane 1, so your code must handle characters beyond the BMP correctly.

Code Points vs. Characters

A crucial distinction: Unicode code points don't always correspond one-to-one with what humans perceive as "characters." Some visual characters can be represented multiple ways:

Despite looking identical to human eyes, Python considers these two strings different. The composed form has length 1, while the decomposed form has length 2. This has serious implications for text processing. String comparison, length calculation, and search operations can give unexpected results. We'll address this with Unicode normalization in the next chapter.

UTF-8: The Encoding That Won

Unicode defines what code points exist, but it doesn't specify how to store them as bytes. That's the job of Unicode Transformation Formats (UTFs). Several exist:

- UTF-32: Uses exactly 4 bytes per character. Simple but wasteful.

- UTF-16: Uses 2 or 4 bytes per character. Common in Windows and Java.

- UTF-8: Uses 1 to 4 bytes per character. Dominant on the web.

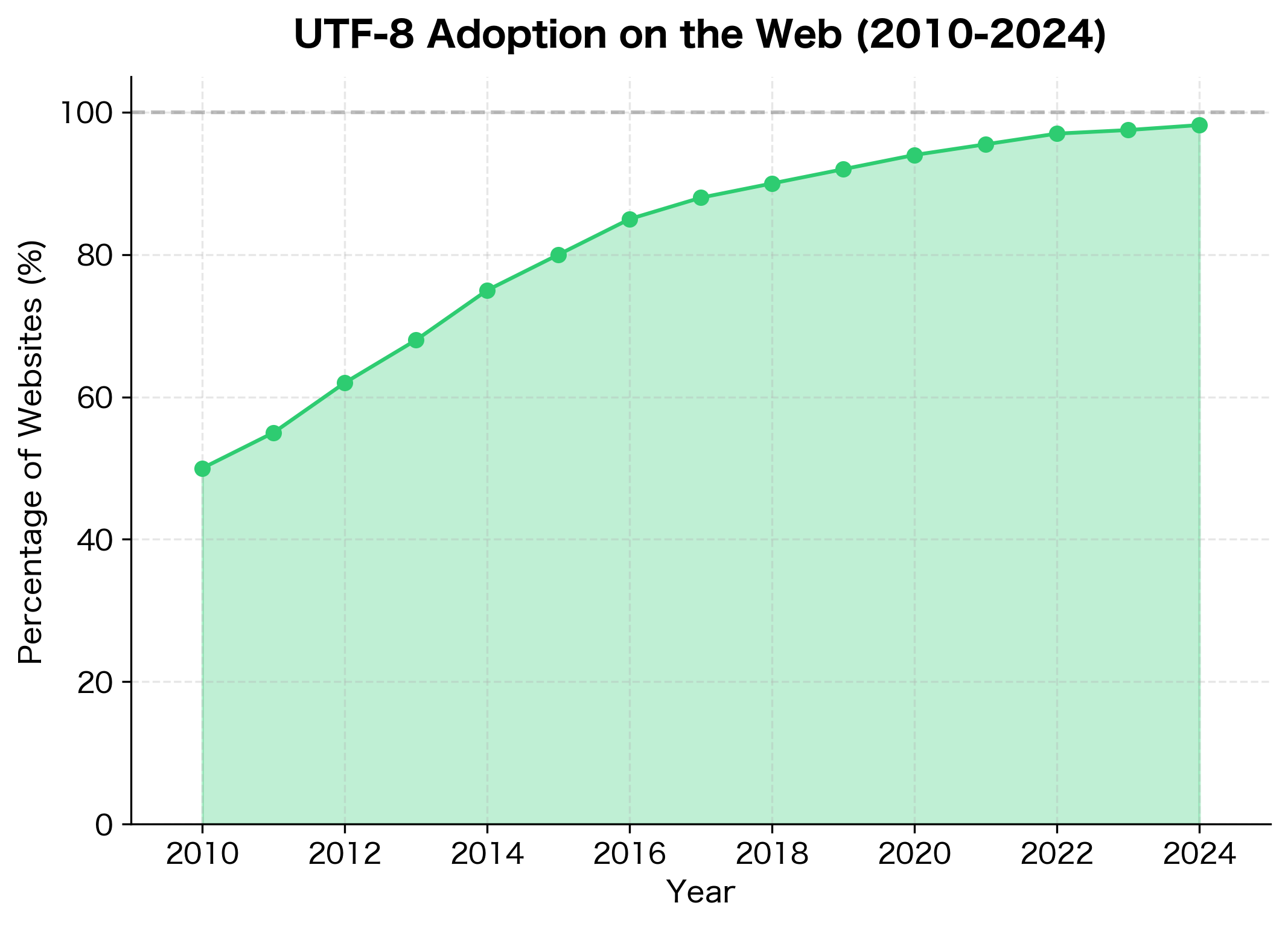

UTF-8, invented by Ken Thompson and Rob Pike in 1992, has become the de facto standard for text on the internet. As of 2024, over 98% of websites use UTF-8.

UTF-8 (Unicode Transformation Format, 8-bit) is a variable-width encoding that represents Unicode code points using one to four bytes. It is backward-compatible with ASCII, meaning any valid ASCII text is also valid UTF-8.

How UTF-8 Works

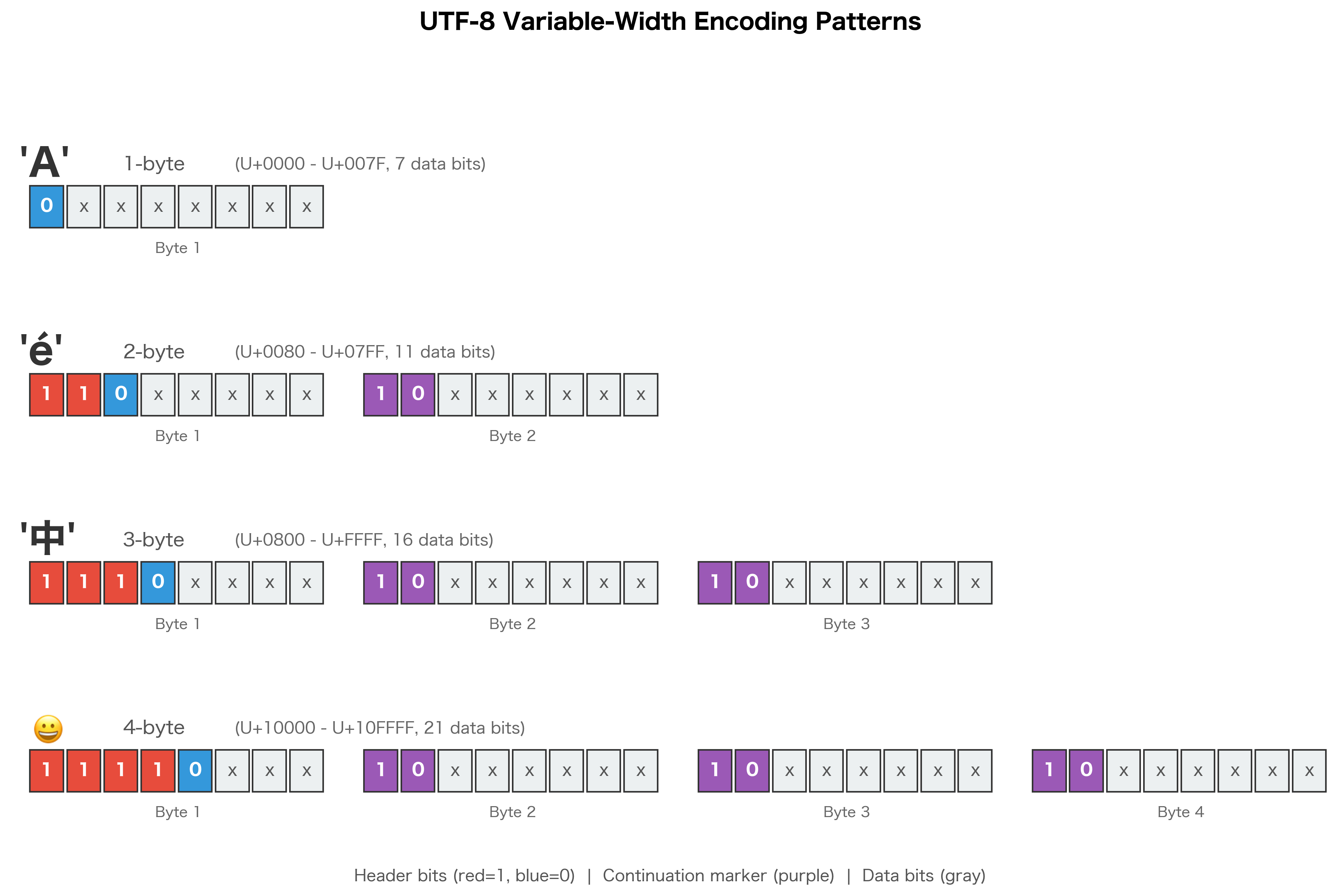

UTF-8's genius lies in its variable-width design. Common characters (ASCII) use just 1 byte, while rarer characters use more:

| Code Point Range | Bytes | Bit Pattern | Data Bits |

|---|---|---|---|

| U+0000 to U+007F | 1 | 0xxxxxxx | 7 |

| U+0080 to U+07FF | 2 | 110xxxxx 10xxxxxx | 11 |

| U+0800 to U+FFFF | 3 | 1110xxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx | 16 |

| U+10000 to U+10FFFF | 4 | 11110xxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx 10xxxxxx | 21 |

The "x" positions in the bit patterns hold the actual code point value. For example, a 2-byte character has 5 data bits in the first byte and 6 in the second, giving total data bits, which can represent values up to (U+07FF).

The leading bits tell you how many bytes the character uses:

- If the first bit is 0, it's a 1-byte character (ASCII)

- If the first bits are 110, it's a 2-byte character

- If the first bits are 1110, it's a 3-byte character

- If the first bits are 11110, it's a 4-byte character

- Continuation bytes always start with 10

Let's see this encoding in action:

Look at the binary patterns. 'A' (code point 65) fits in 7 bits and uses a single byte starting with 0. The French 'é' needs 2 bytes, starting with 110. The Chinese character '中' needs 3 bytes, starting with 1110. And the emoji needs all 4 bytes, starting with 11110.

Why UTF-8 Won

UTF-8's dominance isn't accidental. It has several compelling advantages:

- ASCII compatibility: Any ASCII text is valid UTF-8 without modification. This made adoption painless for the English-speaking computing world that had decades of ASCII data.

- Self-synchronizing: You can jump into the middle of a UTF-8 stream and find character boundaries. Continuation bytes (starting with 10) are distinct from start bytes, so you can always resynchronize.

- No byte-order issues: Unlike UTF-16 and UTF-32, UTF-8 has no endianness problems. The same bytes mean the same thing on any system.

- Efficiency for ASCII-heavy text: English text, code, markup, and many data formats are predominantly ASCII. UTF-8 represents these with no overhead.

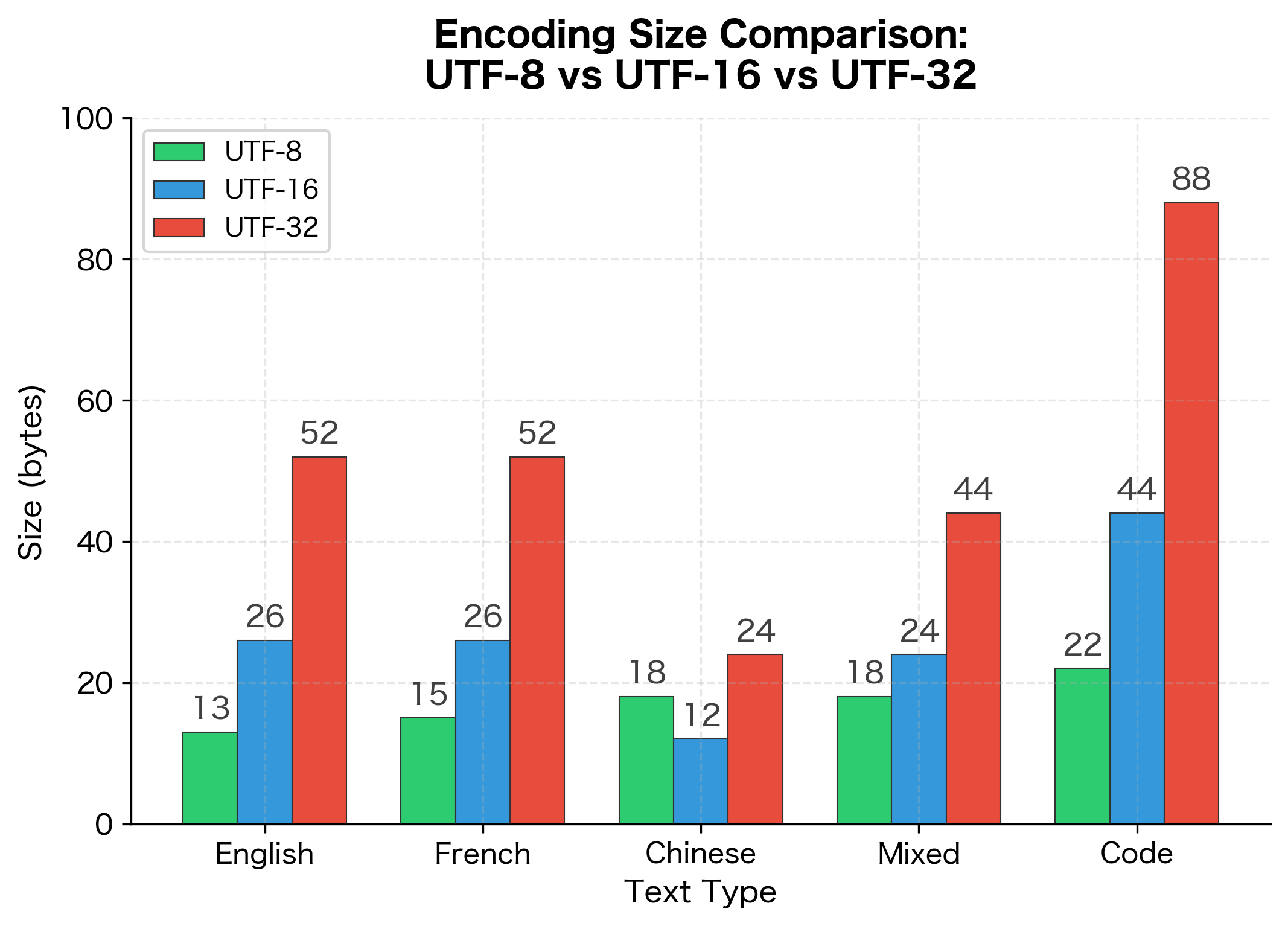

For English text and code, UTF-8 matches the character count exactly since ASCII characters use just 1 byte each. Chinese text requires 3 bytes per character in UTF-8, making it slightly larger than UTF-16, which uses 2 bytes for BMP characters including most CJK ideographs. UTF-32 consistently uses 4 bytes per character regardless of content, resulting in significant overhead for ASCII-heavy text.

Even for Chinese text, UTF-8 is competitive with UTF-16. Only UTF-32 maintains constant character width, at the cost of 4x overhead for ASCII.

Byte Order Marks and Endianness

When using multi-byte encodings like UTF-16 or UTF-32, a question arises: which byte comes first? Consider the code point U+FEFF. In UTF-16, this could be stored as either:

FE FF(big-endian, most significant byte first)FF FE(little-endian, least significant byte first)

A Byte Order Mark is a special Unicode character (U+FEFF) placed at the beginning of a text file to indicate the byte order (endianness) of the encoding. In UTF-8, it serves only as an encoding signature since UTF-8 has no endianness issues.

The BOM character (U+FEFF, "Zero Width No-Break Space") was repurposed to solve this ambiguity. By placing it at the start of a file, readers can determine the byte order:

UTF-8 technically doesn't need a BOM since it has no byte-order ambiguity. However, Microsoft tools often add a UTF-8 BOM (EF BB BF) to indicate the file is UTF-8 rather than some other encoding. This can cause problems with Unix tools that don't expect it.

When reading files of unknown origin, using utf-8-sig instead of utf-8 handles the BOM gracefully.

Encoding Detection

In an ideal world, all text would be clearly labeled with its encoding. In reality, you'll often encounter files with no encoding metadata. How do you figure out what encoding to use?

Heuristic Detection

Encoding detection relies on statistical patterns. Different encodings have characteristic byte sequences:

- UTF-8: Has a specific pattern of continuation bytes

- UTF-16: Often has many null bytes (00) for ASCII text

- ISO-8859-1: Bytes 0x80-0x9F are control characters, rarely used

- Windows-1252: Uses 0x80-0x9F for printable characters like curly quotes

The chardet library implements sophisticated heuristics:

The detector correctly identifies UTF-8 and Shift-JIS with high confidence. Latin-1 detection shows lower confidence because its byte patterns overlap with other encodings. Windows-1252 is often detected as a related encoding since they share most byte mappings. Detection isn't perfect. Short texts provide fewer statistical clues, and some encodings are nearly indistinguishable for certain content. Always verify detected encodings when possible.

Common Detection Pitfalls

Some encoding pairs are particularly tricky to distinguish:

When detection fails or is uncertain, domain knowledge helps. Web pages usually declare encoding in headers or meta tags. XML files often have encoding declarations. When all else fails, UTF-8 is the safest modern default.

Mojibake: When Encoding Goes Wrong

Mojibake (from Japanese 文字化け, "character transformation") refers to garbled text that results from decoding bytes using the wrong character encoding. The term describes the visual appearance of incorrectly decoded text.

Mojibake is the bane of text processing. It occurs when bytes encoded in one system are decoded using a different, incompatible encoding. The result is nonsensical characters that often follow recognizable patterns.

The first case is particularly insidious. UTF-8's multi-byte sequences are valid Latin-1 byte sequences, so no error occurs. Instead, you get garbage like "Héllo Wörld" where each accented character becomes two or three strange characters.

Recognizing Mojibake Patterns

Different encoding mismatches produce characteristic garbage:

When you see patterns like "é" for "é" or "â€"" for "—", you're almost certainly looking at UTF-8 text that was incorrectly decoded as Latin-1 or Windows-1252.

Fixing Mojibake

Sometimes you can reverse mojibake by re-encoding with the wrong encoding and decoding with the right one:

This works because the corruption was reversible. However, some mojibake is destructive, especially when multiple encoding conversions have occurred or when the wrong encoding maps bytes to different code points.

Practical Encoding in Python

Python 3 made a fundamental change from Python 2: strings are Unicode by default. The str type holds Unicode code points, while bytes holds raw byte sequences. Converting between them requires explicit encoding and decoding.

Encoding and Decoding

Error Handling

What happens when encoding or decoding fails? Python offers several error handling strategies:

Each strategy handles unencodable characters differently. The strict mode raises an exception, forcing you to handle the problem explicitly. The ignore mode silently drops characters, which can corrupt your data. The replace mode substitutes question marks, making problems visible. The xmlcharrefreplace and backslashreplace modes preserve information in escaped form, useful for debugging or when round-tripping is needed.

For NLP work, errors='replace' or errors='ignore' can be useful when processing noisy data, but be aware that you're losing information. The surrogateescape error handler is particularly useful for round-tripping binary data that might contain encoding errors.

Reading and Writing Files

Always specify encoding when opening text files:

The file round-trips correctly because we specified encoding='utf-8' explicitly. Without this, Python uses the system's default encoding, which varies across platforms and can lead to data corruption when sharing files between systems.

Processing Text Data

When building NLP pipelines, handle encoding at the boundaries:

The safe_read_text function demonstrates a robust approach: try common encodings in order of likelihood, falling back to automatic detection only when necessary. The normalize_encoding function ensures consistent Unicode representation after reading, which we'll explore in the next chapter.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite Unicode's success, character encoding still presents challenges:

- Legacy data: Vast amounts of text exist in legacy encodings. Converting this data requires knowing the original encoding, which isn't always documented.

- Encoding detection uncertainty: Automatic detection is probabilistic, not deterministic. Short texts or texts mixing languages can confuse detection algorithms.

- Normalization complexity: The same visual character can have multiple Unicode representations. Without normalization, string comparison and searching become unreliable.

- Emoji evolution: New emoji are added regularly, and older systems may not support them. An emoji that renders beautifully on one device might appear as a box or question mark on another.

- Security concerns: Unicode includes many look-alike characters (homoglyphs) that can be exploited for phishing. The Latin 'a' (U+0061) looks identical to the Cyrillic 'а' (U+0430).

Impact on NLP

Character encoding is the foundation upon which all text processing rests. Getting it wrong corrupts your data before any analysis begins. Here's why it matters for NLP:

- Data quality: Training data with encoding errors teaches models garbage. A language model trained on mojibake will reproduce mojibake.

- Tokenization: Many tokenizers operate on bytes or byte-pairs. Understanding UTF-8 encoding helps you understand why tokenizers make certain decisions.

- Multilingual models: Models that handle multiple languages must handle multiple scripts, which means handling Unicode correctly.

- Text normalization: Before comparing or searching text, you need consistent Unicode normalization. Encoding is the prerequisite for normalization.

- Reproducibility: Explicitly specifying encodings makes your code portable across systems with different default encodings.

Key Functions and Parameters

When working with character encoding in Python, these are the essential functions and their most important parameters:

str.encode(encoding, errors='strict')

encoding: The target encoding (e.g.,'utf-8','latin-1','ascii')errors: How to handle unencodable characters. Options include'strict'(raise exception),'ignore'(drop characters),'replace'(use?),'xmlcharrefreplace'(use XML entities),'backslashreplace'(use Python escape sequences)

bytes.decode(encoding, errors='strict')

encoding: The source encoding to interpret the byteserrors: How to handle undecodable bytes. Same options asencode(), plus'surrogateescape'for round-tripping binary data

open(file, mode, encoding=None, errors=None)

encoding: Always specify explicitly for text mode ('r','w'). Use'utf-8'as default,'utf-8-sig'to handle BOM automaticallyerrors: Same options asencode()/decode()

chardet.detect(byte_string)

- Returns a dictionary with

'encoding'(detected encoding name),'confidence'(0.0 to 1.0), and'language'(detected language if applicable) - Higher confidence values indicate more reliable detection

- Short texts yield lower confidence; prefer explicit encoding when possible

Summary

Character encoding bridges the gap between human writing and computer storage. We traced the evolution from ASCII's 128 characters through the fragmented world of regional encodings to Unicode's universal character set and UTF-8's elegant variable-width encoding.

Key takeaways:

- ASCII uses 7 bits for 128 characters, covering only English

- Unicode assigns unique code points to over 149,000 characters across all writing systems

- UTF-8 encodes Unicode using 1-4 bytes, with ASCII compatibility and no endianness issues

- Mojibake results from decoding bytes with the wrong encoding

- Always specify encoding when reading or writing text files in Python

- Use UTF-8 as your default encoding for new projects

- Encoding detection is heuristic and imperfect; verify when possible

In the next chapter, we'll build on this foundation to explore text normalization, addressing the challenge of multiple Unicode representations for the same visual character.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about character encoding.

Comments