F-distribution, F-test for comparing variances, F-test in regression, and nested model comparison. Learn how F-tests extend hypothesis testing beyond means to variance analysis and model comparison.

This article is part of the free-to-read Machine Learning from Scratch

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

The F-Test and F-Distribution

So far in this series, we've focused on comparing means: is this sample mean different from a hypothesized value (one-sample t-test)? Do these two groups have different average outcomes (two-sample t-test)? But means tell only part of the story. Two manufacturing processes might produce widgets with the same average diameter, yet one process might be wildly inconsistent while the other is remarkably precise. A financial portfolio might have the same expected return as another, but with far greater volatility. In these cases, variance is what matters.

The F-test addresses questions about variance. Named after Sir Ronald A. Fisher, one of the founders of modern statistics, the F-test emerged from Fisher's work on agricultural experiments in the 1920s. Fisher realized that comparing sources of variation, not just averages, was essential for understanding experimental results. His insights led to both the F-distribution and the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) framework that revolutionized experimental science.

This chapter introduces the F-distribution and shows how F-tests answer three important types of questions:

- Do two populations have equal variance? (Essential for choosing between pooled and Welch's t-tests)

- Does a regression model explain significant variation? (Testing overall model significance)

- Do additional predictors improve a model? (Comparing nested regression models)

Understanding F-tests here will prepare you for ANOVA, which extends these ideas to compare means across multiple groups by decomposing total variation into components.

Why Compare Variances?

Before diving into the mathematics, let's understand why variance comparisons matter in practice.

Quality control and manufacturing: A factory produces bolts with a target diameter. Two machines might produce bolts with the same average diameter, but if Machine A's output varies by mm while Machine B's varies by mm, Machine B will produce far more defective bolts. Comparing variances identifies the less consistent process.

Checking t-test assumptions: The pooled two-sample t-test assumes equal variances between groups. Before using this test, you might want to verify this assumption. The F-test provides a formal way to check.

Investment risk: Two stocks might have the same expected annual return of 8%, but if Stock A has a standard deviation of 5% and Stock B has 25%, they represent very different risk profiles. Comparing variances quantifies this difference.

Measurement precision: When comparing two laboratory instruments or two human raters, you care not just about whether they give the same average reading, but whether one is more variable (less precise) than the other.

The F-Distribution: Where It Comes From

The F-distribution arises naturally when comparing two independent estimates of variance. To understand why, we need to trace through the mathematical foundations.

Building Block: Chi-Squared Distribution

Recall from earlier chapters that when you estimate variance from a sample of observations drawn from a normal population with true variance , the quantity:

follows a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom. This result reflects the fact that is computed from observations but loses one degree of freedom because we estimate the mean from the same data.

From Two Samples to the F-Distribution

Now suppose we have two independent samples from populations with variances and :

- Sample 1: observations, sample variance

- Sample 2: observations, sample variance

Each sample variance, properly scaled, follows a chi-squared distribution:

The F-distribution is defined as the ratio of two independent chi-squared random variables, each divided by its degrees of freedom:

Substituting our variance estimates:

The Key Simplification Under the Null Hypothesis

Here's the beautiful part. Under the null hypothesis that , the ratio , and we get:

where and .

The unknown common variance cancels out! This is why the F-test works: we can test whether two population variances are equal without knowing what those variances actually are. We only need the ratio of the sample variances, and we know its distribution under the null hypothesis.

Properties of the F-Distribution

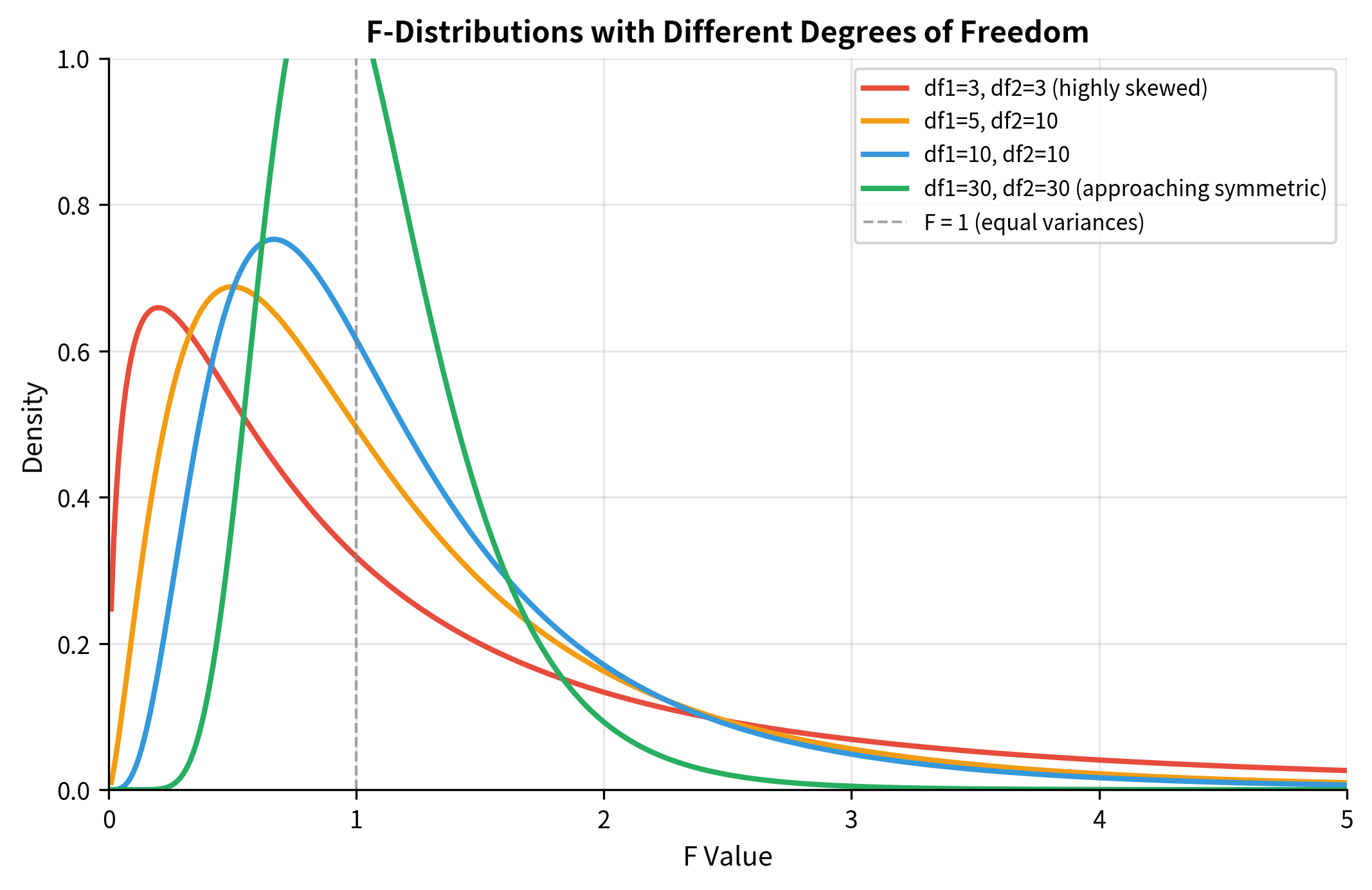

The F-distribution has distinctive characteristics that set it apart from the normal and t-distributions:

Two degrees of freedom parameters: The F-distribution requires both (numerator) and (denominator). The order matters: is a different distribution from . This asymmetry reflects the fact that we're comparing a specific numerator variance to a specific denominator variance.

Always non-negative: Since F is a ratio of variances (squared quantities), it cannot be negative. The distribution is defined only for .

Right-skewed: The F-distribution has a long right tail, especially when degrees of freedom are small. As both and increase, the distribution becomes more symmetric and concentrated.

Mean near 1 under the null: When comparing equal variances, F should be approximately 1. The expected value is for , which approaches 1 as grows large.

Reciprocal relationship: If , then . This is useful for two-tailed tests and for ensuring the larger variance is in the numerator.

F-Test for Comparing Two Variances

The most direct application of the F-test compares variances between two independent populations.

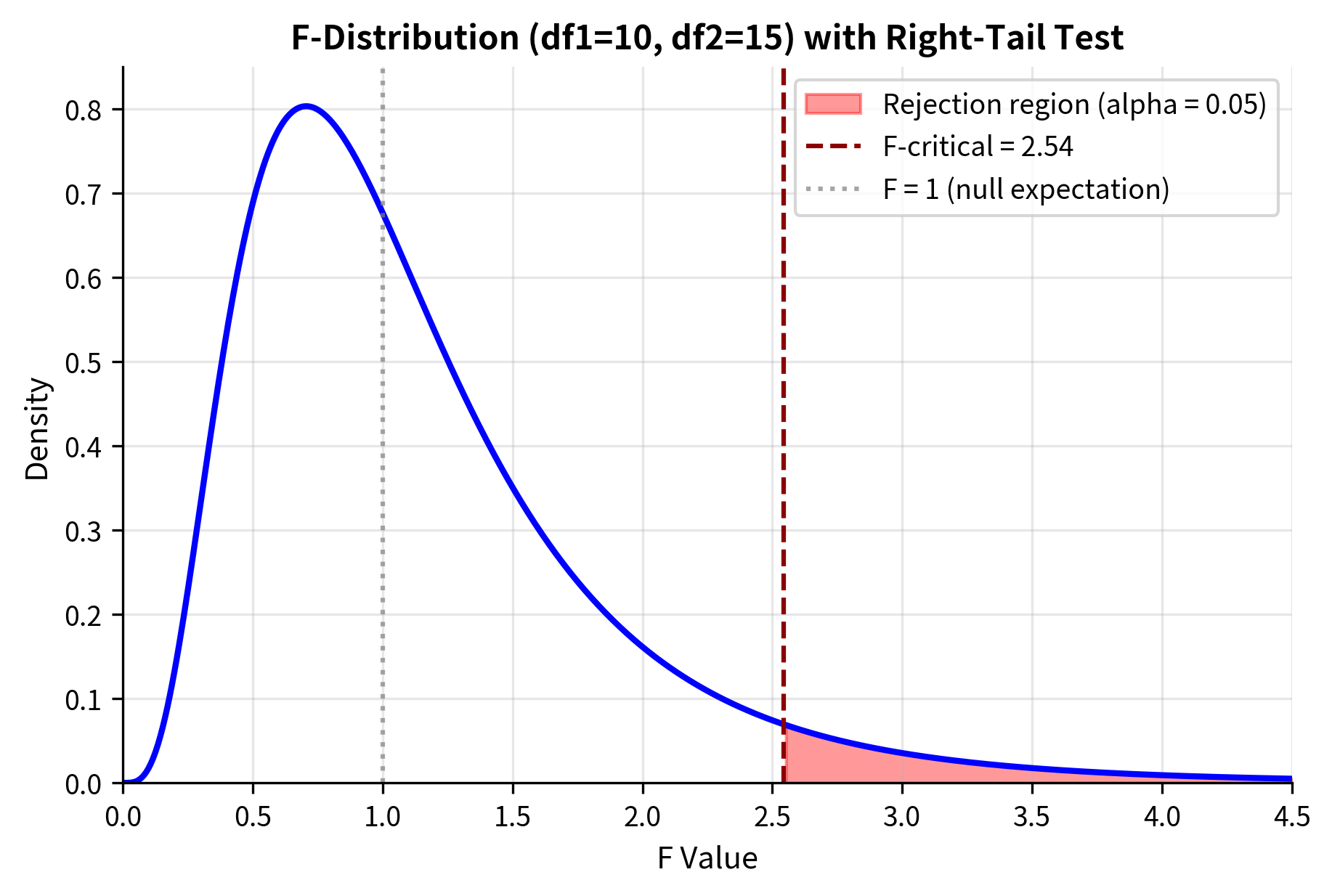

Hypotheses and Test Statistic

Null hypothesis: (population variances are equal)

Alternative hypotheses:

- Two-sided:

- One-sided (greater):

- One-sided (less):

where and are the sample variances.

Convention: Place the larger sample variance in the numerator so that . This simplifies interpretation: if is much larger than 1, it suggests the numerator variance is genuinely larger than the denominator variance.

Degrees of freedom: (numerator), (denominator)

P-value calculation:

- One-sided (greater):

- Two-sided: Since the F-distribution is not symmetric, we compute

Worked Example: Manufacturing Process Comparison

A quality engineer wants to compare the consistency of two production lines making precision components. She randomly samples 20 components from Line A and 25 from Line B, measuring a critical dimension.

Important Caveats

The F-test for comparing variances is highly sensitive to non-normality. If the underlying populations are not normally distributed, the F-test can give misleading results even with moderate sample sizes. This is unlike the t-test, which is fairly robust to non-normality.

For this reason, many statisticians prefer more robust alternatives:

- Levene's test: Uses absolute deviations from the mean or median; robust to non-normality

- Brown-Forsythe test: A variant of Levene's test using the median

- Bartlett's test: More powerful under normality but sensitive to non-normality

When checking the equal variance assumption for a t-test:

- Visual inspection (boxplots, standard deviation ratio) is often sufficient

- If a formal test is needed, use Levene's test rather than the F-test

- When in doubt about equal variances, simply use Welch's t-test, which doesn't assume equal variances

F-Test in Regression: Overall Model Significance

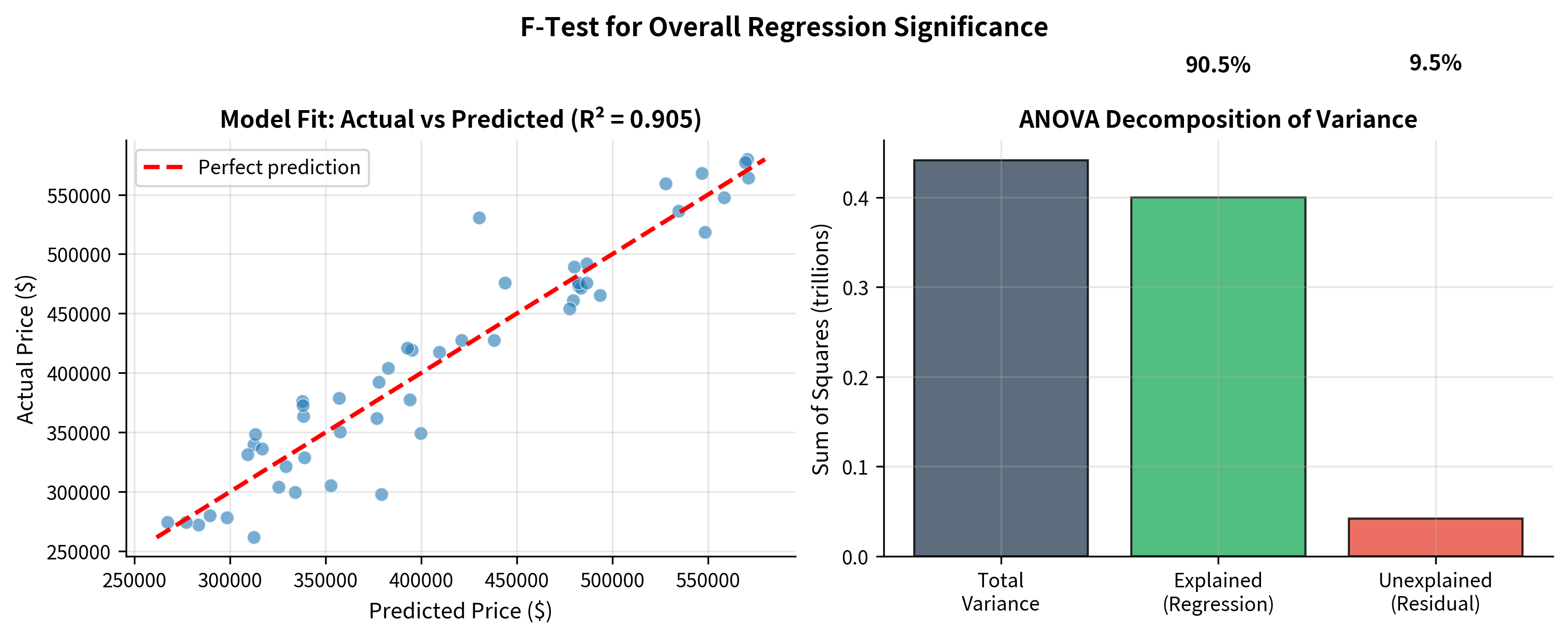

Beyond comparing two variances, the F-test plays a central role in regression analysis. When you fit a regression model, an immediate question is: does this model explain any variation at all?

The ANOVA Decomposition

Every regression model partitions the total variation in the response variable into two components:

where:

- = : Total variation in

- = : Variation explained by the model

- = : Variation left unexplained

The F-test asks: is the explained variation large enough, relative to the unexplained variation, to conclude that the model has real predictive value?

The F-Statistic for Regression

where:

- = number of predictors (excluding intercept)

- = number of observations

- = "Mean Square" = sum of squares divided by degrees of freedom

Degrees of freedom:

- Numerator: (one for each predictor)

- Denominator: (residual degrees of freedom)

Null hypothesis: (all predictor coefficients are zero)

If the null is true, none of the predictors help explain , and should be similar to , giving . A large F indicates the model explains more variation than expected by chance.

Worked Example: Multiple Regression

A researcher studies factors affecting house prices, fitting a model with square footage and number of bedrooms as predictors.

Connection to R-Squared

The F-statistic is directly related to :

This shows that:

- Higher → larger F → smaller p-value

- More predictors () → penalizes the F-statistic (need more explained variance to be significant)

- Larger sample size () → more power to detect small as significant

Comparing Nested Models

One of the most powerful applications of the F-test is comparing nested regression models. A model is "nested" within another if it's a special case obtained by setting some coefficients to zero.

Question: Does adding extra predictors significantly improve the model?

The Nested Model F-Test

Consider:

- Reduced model: (1 predictor)

- Full model: (3 predictors)

The reduced model is nested within the full model (set ).

Interpretation:

- Numerator: Improvement (reduction in residual SS) per additional predictor

- Denominator: Unexplained variance per degree of freedom in the full model

- = number of additional predictors being tested

Null hypothesis: The additional predictors have no effect ()

Worked Example: Model Selection

A researcher wants to know if adding interaction terms improves a base model.

The F-test correctly identifies:

- Adding (true predictor) significantly improves the model

- Adding the interaction (true effect) significantly improves the model

- Adding (pure noise) does not significantly improve the model

When to Use Nested Model Comparison

This technique is useful for:

- Variable selection: Testing whether specific predictors should be included

- Testing interactions: Does an interaction term add explanatory power?

- Polynomial terms: Does a quadratic term improve on a linear model?

- Group comparisons: Testing whether different groups need different slopes (via interaction with a group indicator)

Assumptions and Limitations

Assumptions of F-Tests

1. Independence: Observations must be independent within and between groups

2. Normality: The underlying populations should be normally distributed

- The F-test for variances is highly sensitive to non-normality

- The regression F-test is more robust, especially with larger samples

3. Random sampling: Data should come from random samples of the populations of interest

Robustness Considerations

| Application | Robustness to Non-Normality |

|---|---|

| Comparing two variances | Poor - Use Levene's test instead |

| Overall regression significance | Moderate - OK with n > 30 |

| Nested model comparison | Moderate - OK with larger samples |

| ANOVA (covered next) | Moderate - OK if groups have similar sizes |

Summary

The F-test and F-distribution are fundamental tools for comparing variances and testing model adequacy:

The F-distribution:

- Arises from the ratio of two independent variance estimates

- Parameterized by two degrees of freedom (numerator and denominator)

- Always non-negative, right-skewed, centered near 1 under the null hypothesis

- Converges to symmetry as degrees of freedom increase

F-test for comparing variances:

- Tests

- Statistic: (larger variance in numerator)

- Sensitive to non-normality; prefer Levene's test in practice

F-test in regression:

- Overall significance: Tests whether any predictors have explanatory power

- Decomposes total variance into explained and unexplained components

- Large F indicates model explains more variation than expected by chance

Nested model comparison:

- Tests whether additional predictors significantly improve a model

- Compares reduction in residual variance to residual variance of full model

- Essential for variable selection and model building

Practical guidance:

- For comparing variances: Use Levene's test (more robust) or visual inspection

- For regression: The F-test from standard output tests overall model significance

- For model selection: Nested model F-tests guide inclusion of predictors

What's Next

This chapter introduced the F-distribution and F-tests for comparing variances and testing regression models. The next chapter on ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) shows how the F-test extends to comparing means across three or more groups. ANOVA uses the same variance decomposition logic: partition total variation into between-group and within-group components, then test whether between-group variation is large enough to conclude the means differ.

After ANOVA, subsequent chapters cover:

- Type I and Type II errors: Understanding the two ways hypothesis tests can go wrong

- Power and sample size: Planning studies to detect meaningful effects

- Effect sizes: Quantifying practical significance beyond statistical significance

- Multiple comparisons: Controlling error rates when conducting many tests

All of these build on the foundation of understanding how variation is partitioned and compared, which you've learned through z-tests, t-tests, and now F-tests.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about the F-test and F-distribution.

Comments