Cohen's d, practical significance, interpreting effect sizes, and why tiny p-values can mean tiny effects. Learn to distinguish statistical significance from practical importance.

This article is part of the free-to-read Machine Learning from Scratch

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Effect Sizes and Statistical Significance

In 2005, researchers published a study claiming that listening to Mozart's music temporarily increased IQ. The finding was statistically significant (p < 0.05), and the "Mozart Effect" became a cultural phenomenon. Parents rushed to buy classical music CDs for their babies, and Georgia's governor even proposed giving every newborn a free Mozart CD.

But the original study had a critical omission: it never reported the effect size. When later researchers calculated it, they found d ≈ 0.15, a tiny effect that explained less than 1% of the variance in IQ scores. The effect, while statistically detectable, was so small that it had no practical importance whatsoever. The statistical significance was real; the practical significance was essentially zero.

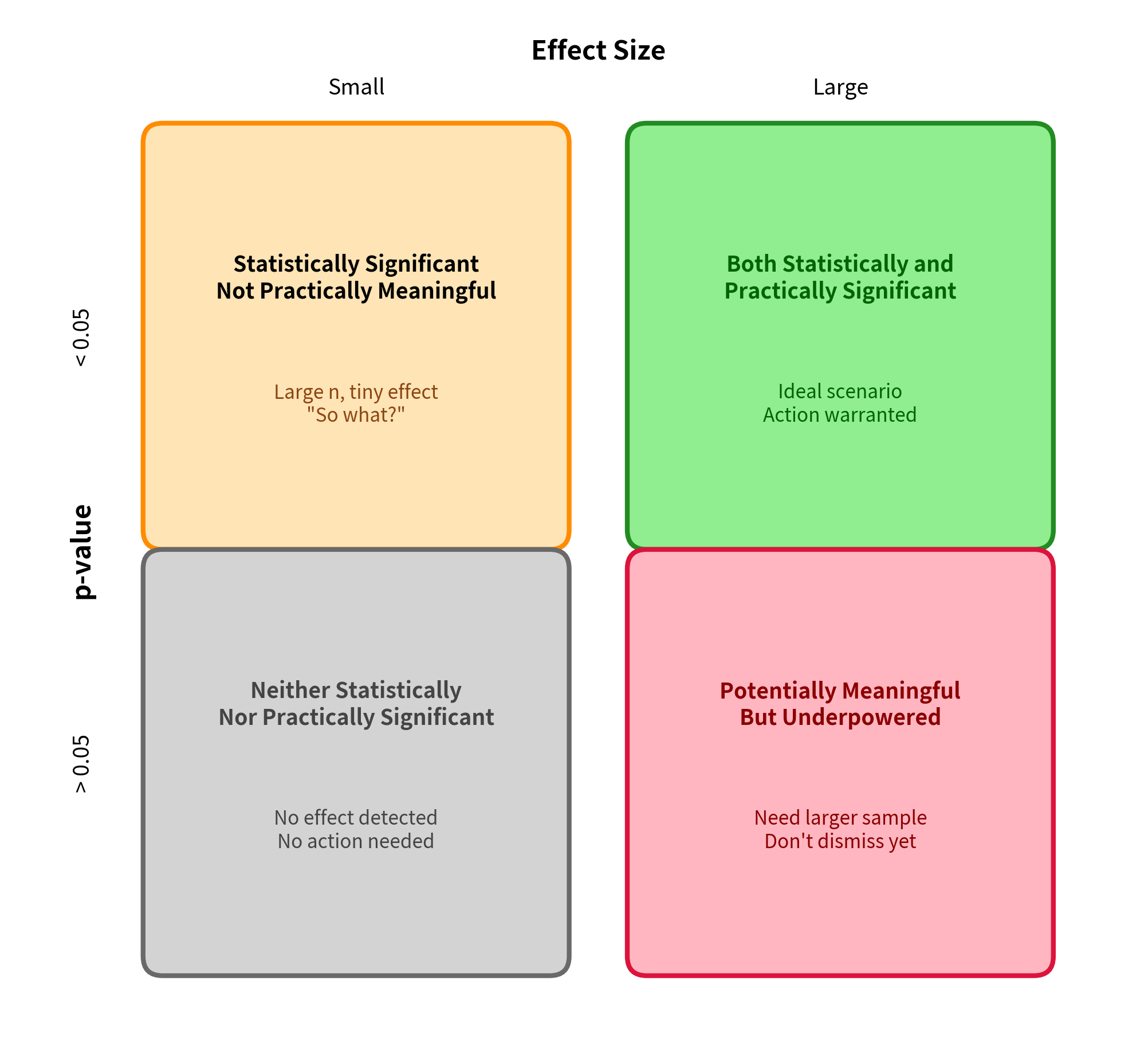

This distinction between statistical significance and practical significance is one of the most important concepts in applied statistics. A p-value tells you whether an effect is distinguishable from zero given your sample size. An effect size tells you whether that effect is large enough to actually matter. Both pieces of information are essential for sound scientific interpretation.

Why Effect Sizes Matter

Statistical significance has a fundamental limitation: it depends heavily on sample size. With a large enough sample, you can detect effects so tiny that they have no practical importance. With a small sample, you might miss effects that are genuinely meaningful.

This example illustrates a fundamental truth: p-values measure evidence against the null hypothesis, not the magnitude of the effect. Effect sizes fill this gap.

Cohen's d: The Standard Effect Size for Mean Differences

The most widely used effect size for comparing two group means is Cohen's d, which expresses the difference between means in standard deviation units.

The Formula

where:

- is the difference between group means

- is the pooled standard deviation:

Why Standardize?

Raw mean differences are meaningful when you understand the scale. "The treatment improved test scores by 10 points" is immediately interpretable if you know what 10 points means on that test.

But raw differences can't be compared across studies using different measures. Is a 10-point improvement on one test comparable to a 5-point improvement on another? Without knowing the variability of each test, it's impossible to say.

Standardization solves this problem. A Cohen's d of 0.5 always means "half a standard deviation," regardless of whether the original measure was test scores, reaction times, or blood pressure. This makes effect sizes comparable across completely different domains.

Cohen's Benchmarks

Jacob Cohen proposed rough benchmarks for interpreting d:

| Effect Size | Cohen's d | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Small | 0.2 | Subtle, may require large samples to detect |

| Medium | 0.5 | Noticeable, often practically meaningful |

| Large | 0.8 | Substantial, usually obvious |

Practical Interpretation

Cohen's benchmarks are useful starting points, but context matters enormously. Consider:

- Medical interventions: A d = 0.2 effect on mortality might save thousands of lives and justify widespread adoption.

- Educational interventions: A d = 0.8 effect on test scores might not matter if the intervention costs $10,000 per student.

- Business decisions: A d = 0.1 effect on conversion rates might be worth millions in a large-scale A/B test.

Always interpret effect sizes in the context of:

- The practical significance of the outcome

- The cost of achieving the effect

- Comparison to other interventions in the field

Computing Cohen's d

Variants of Cohen's d

Several variations of Cohen's d exist for different situations:

Hedges' g: Correcting for Small Sample Bias

Cohen's d has a slight upward bias in small samples. Hedges' g applies a correction:

Glass's Delta: Unequal Variances

When the treatment might change variability, use the control group's standard deviation as the denominator:

Effect Sizes for Other Designs

Paired Samples: Cohen's d_z

For paired designs (before/after, matched pairs), standardize by the standard deviation of differences:

where is the mean of pairwise differences and is their standard deviation.

ANOVA: Eta-Squared and Omega-Squared

For ANOVA, effect sizes describe the proportion of variance explained:

Eta-squared (η²):

Omega-squared (ω²), less biased:

| Effect Size | η² / ω² | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Small | 0.01 | 1% of variance explained |

| Medium | 0.06 | 6% of variance explained |

| Large | 0.14 | 14% of variance explained |

Correlation: r as an Effect Size

Pearson's correlation coefficient r is itself an effect size, measuring the strength of linear relationship:

| Effect Size | r | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Small | 0.1 | Weak relationship |

| Medium | 0.3 | Moderate relationship |

| Large | 0.5 | Strong relationship |

The coefficient of determination r² gives the proportion of variance shared between variables.

Proportions: Cohen's h and Odds Ratio

For comparing proportions, several effect sizes are available:

Cohen's h (arcsine transformation):

Odds Ratio:

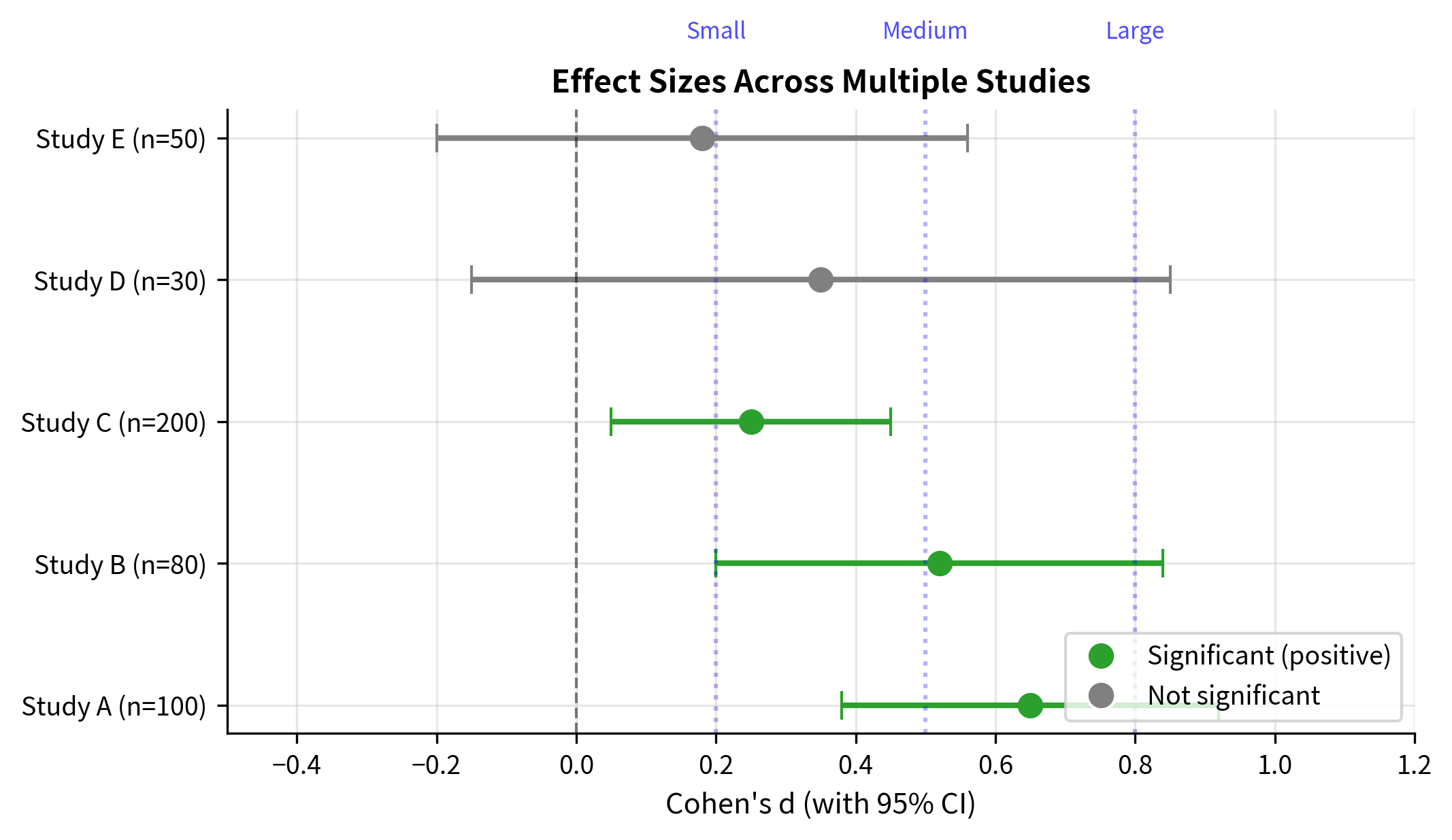

Confidence Intervals for Effect Sizes

Point estimates of effect sizes have uncertainty. Confidence intervals provide a range of plausible values:

Statistical vs. Practical Significance

The distinction between statistical and practical significance is crucial for sound interpretation.

Statistical Significance

- Answers: "Is the effect distinguishable from zero?"

- Depends on: Sample size, effect size, variability

- Limitation: Achievable for any non-zero effect with large enough n

Practical Significance

- Answers: "Is the effect large enough to matter?"

- Depends on: Context, costs, benefits, alternatives

- Limitation: Requires domain knowledge to interpret

A Complete Example

Best Practices for Reporting Effect Sizes

What to Report

- Always report effect sizes alongside p-values

- Include confidence intervals when possible

- Use the appropriate effect size for your design

- Interpret in context

APA Style Reporting

Summary Table Format

| Measure | Control | Treatment | Effect Size | 95% CI | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test Score | 50.2 ± 10.1 | 58.3 ± 9.8 | d = 0.81 | [0.35, 1.27] | Large effect |

Summary

Effect sizes are essential complements to p-values that quantify the magnitude, not just the existence, of effects:

Cohen's d measures standardized mean differences:

- Small: d ≈ 0.2

- Medium: d ≈ 0.5

- Large: d ≈ 0.8

Variants exist for different situations:

- Hedges' g for small samples

- Glass's Δ for unequal variances

- Cohen's d_z for paired samples

Other effect sizes:

- η² and ω² for ANOVA (proportion of variance)

- r for correlations

- Cohen's h and odds ratios for proportions

Key principles:

- Statistical significance ≠ practical significance

- Large samples can detect trivial effects

- Always interpret effect sizes in context

- Report confidence intervals when possible

What's Next

Understanding effect sizes prepares you for the multiple comparisons problem. When you conduct many tests simultaneously, each with its own effect size estimate, error rates compound and require special correction methods. You'll learn:

- Why multiple testing inflates false positive rates

- Bonferroni correction and its limitations

- False Discovery Rate (FDR) control

- When and how to apply corrections

The final section ties all hypothesis testing concepts together with practical guidelines for analysis and reporting.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about effect sizes and the distinction between statistical and practical significance.

Comments