Understanding false positives, false negatives, statistical power, and the tradeoff between error types. Learn how to balance Type I and Type II errors in study design.

This article is part of the free-to-read Machine Learning from Scratch

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Type I and Type II Errors

In 1999, British solicitor Sally Clark was convicted of murdering her two infant sons, who had died suddenly in 1996 and 1998. The prosecution's star witness, pediatrician Sir Roy Meadow, testified that the probability of two children in an affluent family dying from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) was 1 in 73 million. This number, obtained by squaring the 1 in 8,543 probability of a single SIDS death, seemed to prove Clark's guilt beyond any reasonable doubt.

But the calculation was catastrophically wrong. It assumed the two deaths were independent events, ignoring known genetic and environmental factors that make SIDS more likely in families who have already experienced it. More importantly, even if the probability were correct, it confused two very different questions: "What is the probability of two SIDS deaths?" versus "Given two infant deaths, what is the probability the mother is a murderer rather than a victim of tragic coincidence?"

Clark spent three years in prison before her conviction was overturned. The court recognized what statisticians call the prosecutor's fallacy: confusing the probability of the evidence given innocence with the probability of innocence given the evidence. Sally Clark's case illustrates the devastating real-world consequences of misunderstanding error rates in hypothesis testing.

Every statistical test involves making a decision under uncertainty, and every decision carries the risk of error. Understanding these errors, their nature, their probabilities, and the tradeoffs between them, is essential for anyone who uses statistics to make decisions.

The Two Ways Tests Can Fail

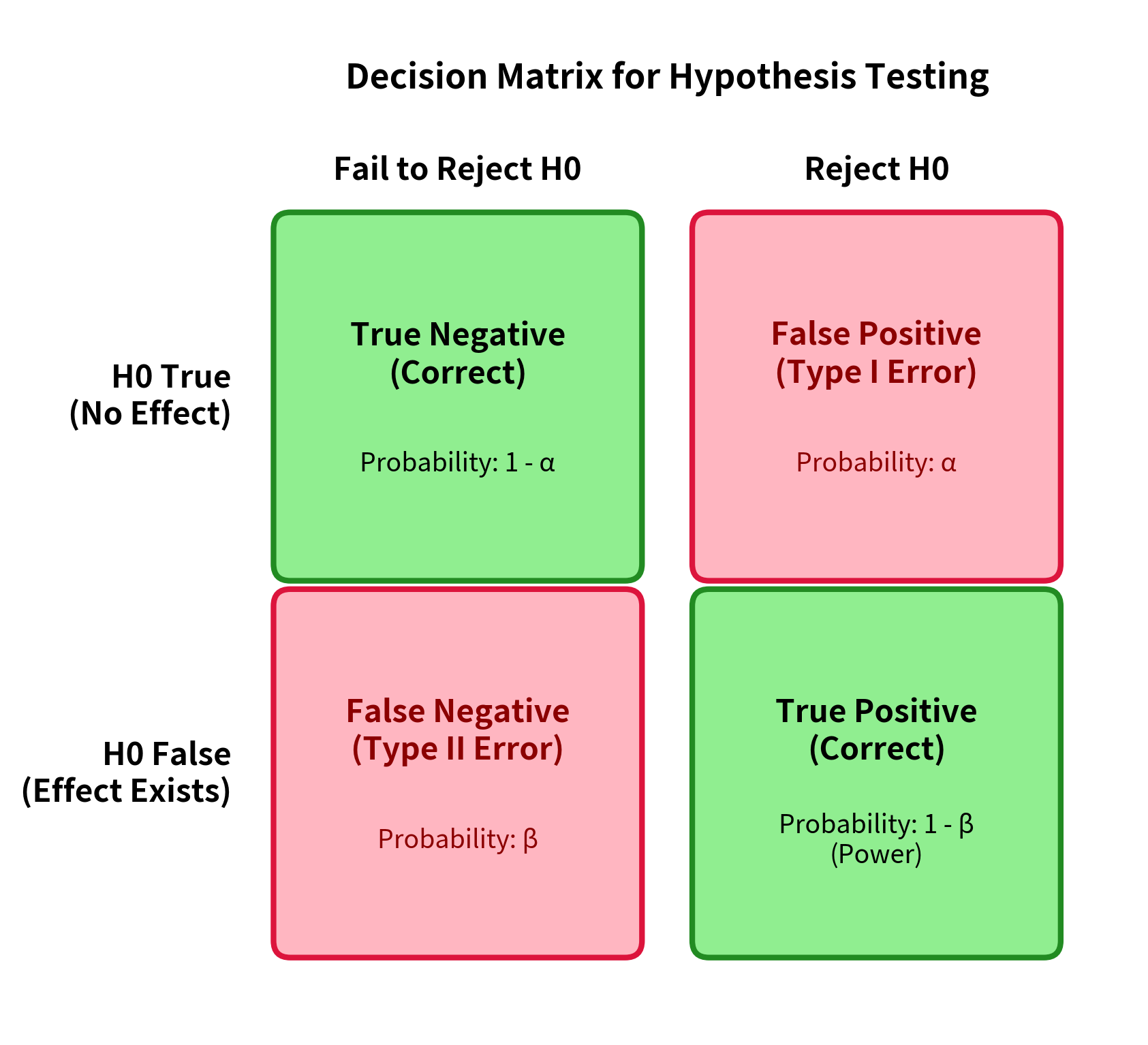

When we conduct a hypothesis test, we are making a binary decision: reject the null hypothesis or fail to reject it. Reality also has two states: either the null hypothesis is true, or it is false. This creates a 2×2 matrix of possible outcomes.

Let's define these four outcomes precisely:

-

True Negative: The null hypothesis is true (no effect exists), and we correctly fail to reject it. This is a correct decision.

-

True Positive: The null hypothesis is false (an effect exists), and we correctly reject it. This is a correct decision, and its probability is called power.

-

Type I Error (False Positive): The null hypothesis is true (no effect exists), but we incorrectly reject it. We claim to have found something that isn't there.

-

Type II Error (False Negative): The null hypothesis is false (an effect exists), but we fail to reject it. We miss a real effect that is actually there.

Type I Errors: The False Alarm

A Type I error occurs when you reject a true null hypothesis. In plain language: you conclude that something interesting is happening when, in reality, nothing is going on. You've raised a false alarm.

The Probability of Type I Error: α

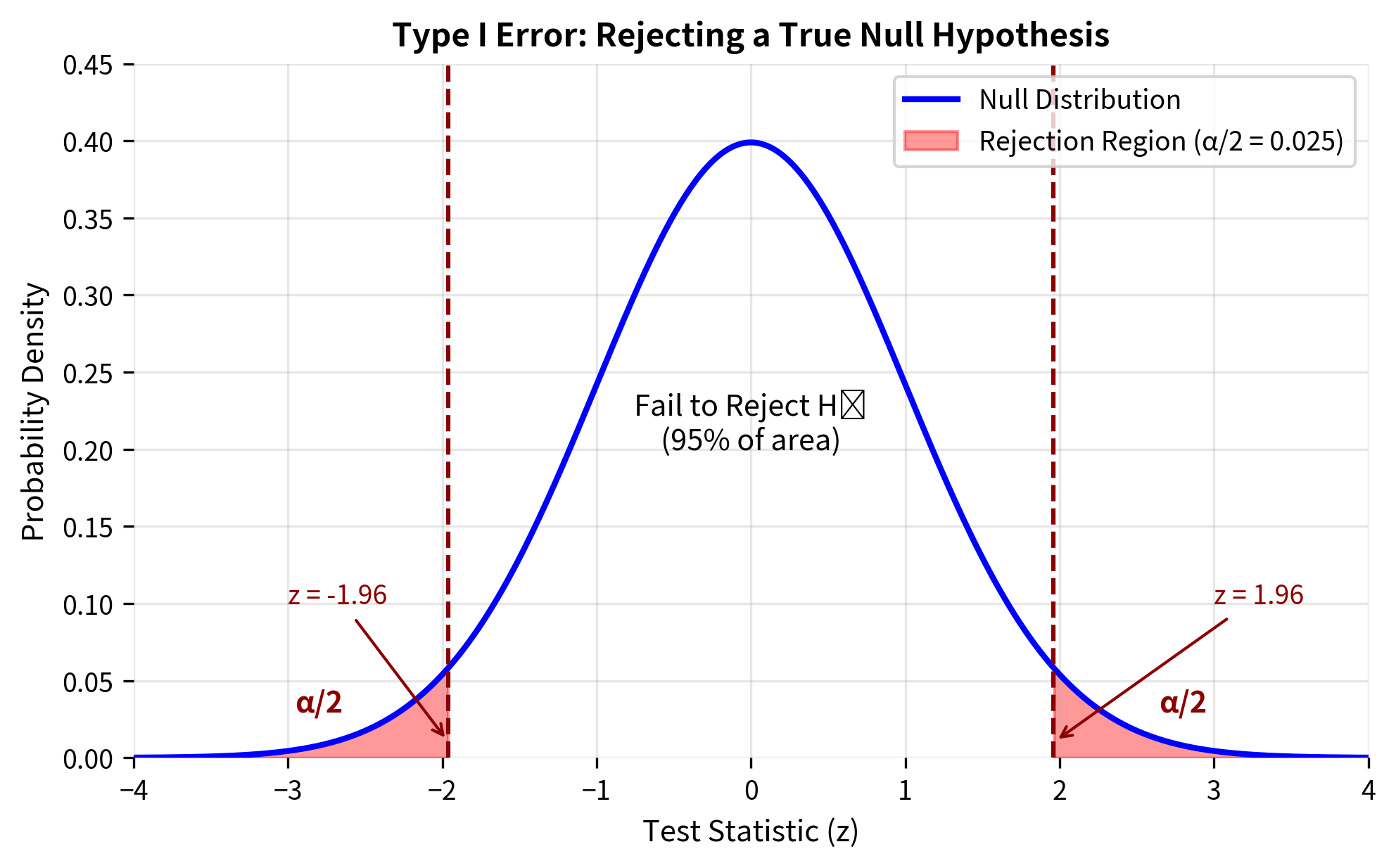

The probability of a Type I error is denoted by the Greek letter alpha (α), and it equals the significance level you choose for your test. When you set α = 0.05, you are accepting a 5% probability of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true.

Mathematically:

This is a conditional probability: the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis, given that the null hypothesis is actually true. It represents the false positive rate of your test.

Why α Equals the Significance Level

To understand why α equals our chosen significance level, recall how hypothesis testing works. We:

- Assume the null hypothesis is true

- Calculate the sampling distribution of our test statistic under this assumption

- Determine what values of the test statistic would be "extreme enough" to reject

- The significance level is precisely the probability of observing such extreme values when is true

For a two-tailed z-test with α = 0.05:

The Key Insight: You Control α

Unlike many other aspects of hypothesis testing, the significance level α is under your direct control. You choose it before conducting the test, based on the consequences of false positives in your specific context.

The conventional choice of α = 0.05 is just that, a convention. It was popularized by Ronald Fisher in the early 20th century as a reasonable default, but it is not a universal law. Different contexts warrant different choices:

| Context | Typical α | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory research | 0.10 | Missing effects is costly; expect replication |

| Standard scientific research | 0.05 | Convention balancing Type I and II errors |

| Confirmatory/regulatory | 0.01 | False positives have serious consequences |

| Particle physics discoveries | ~0.0000003 (5σ) | Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence |

| Genome-wide association | 5 × 10⁻⁸ | Multiple testing across millions of variants |

Real-World Consequences of Type I Errors

Type I errors can have serious consequences across many domains:

Medical diagnosis: A healthy patient is told they have cancer. This causes severe psychological distress, leads to invasive follow-up procedures (biopsies, additional imaging), and may result in unnecessary treatment with harmful side effects.

Criminal justice: An innocent person is convicted of a crime. This is the scenario our legal systems are designed to prevent: the presumption of innocence exists precisely because Type I errors (convicting the innocent) are considered worse than Type II errors (acquitting the guilty).

Drug approval: The FDA approves a drug that is actually no better than placebo. Patients take an ineffective medication, potentially experiencing side effects without any benefit, while being denied treatments that might actually work.

A/B testing: A company deploys a new website design based on a "significant" result that was actually just noise. Engineering resources are wasted, and if the change is actually harmful, user experience suffers.

Scientific research: A researcher publishes a "discovery" that is just a statistical fluke. Other researchers waste time and resources trying to replicate or build on the finding. The scientific literature becomes polluted with false results.

Type II Errors: The Missed Discovery

A Type II error occurs when you fail to reject a false null hypothesis. In plain language: a real effect exists, but your test fails to detect it. You've missed a genuine discovery.

The Probability of Type II Error: β

The probability of a Type II error is denoted by the Greek letter beta (β):

This is also a conditional probability: the probability of not rejecting the null hypothesis, given that it is actually false.

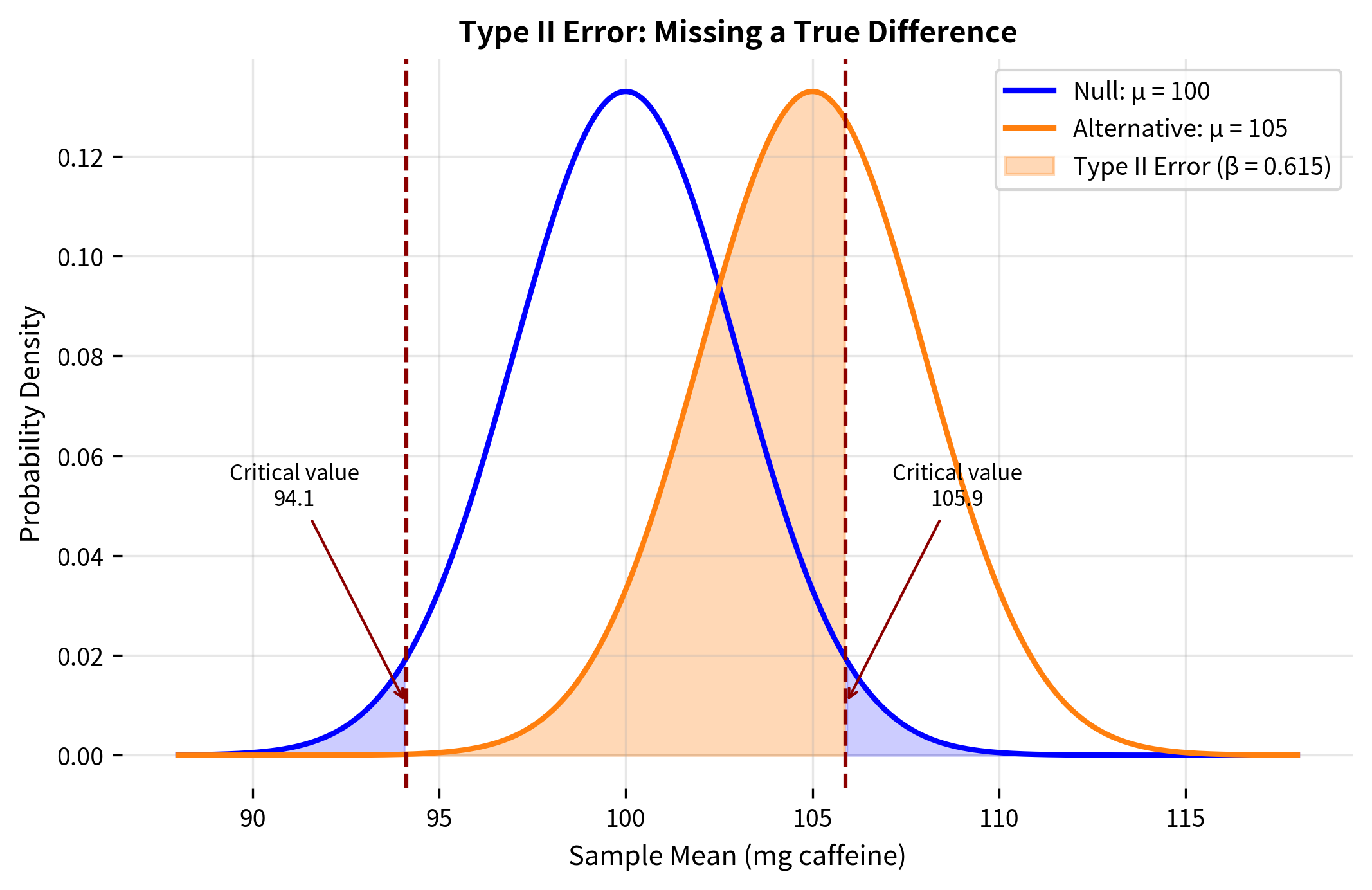

Computing β: The Mathematics

Unlike α, which you simply choose, β must be calculated based on several factors. The calculation requires specifying an alternative hypothesis: you need to know what the true state of the world is to compute the probability of missing it.

Let's work through the mathematics for a one-sample z-test. Suppose:

- Null hypothesis:

- True population mean: (where )

- Known population standard deviation:

- Sample size:

- Significance level: (two-tailed test)

Step 1: Find the critical values under

Under the null hypothesis, the test statistic follows a standard normal distribution. The critical values for a two-tailed test at significance level α are:

For α = 0.05:

Step 2: Convert critical z-values to critical sample means

We reject if falls outside the interval:

Step 3: Calculate β under the alternative

A Type II error occurs when falls in the "fail to reject" region even though the true mean is . Under the alternative:

The probability of not rejecting is:

Standardizing using the true mean :

where is the standard normal CDF.

Worked Example: Calculating β

Let's calculate β for a concrete scenario.

Scenario: A coffee company claims their beans have a mean caffeine content of 100 mg per cup (). A consumer group suspects the true content is 105 mg (). They plan to test 25 cups, and caffeine content is known to have σ = 15 mg.

Let's visualize what's happening:

What Determines β?

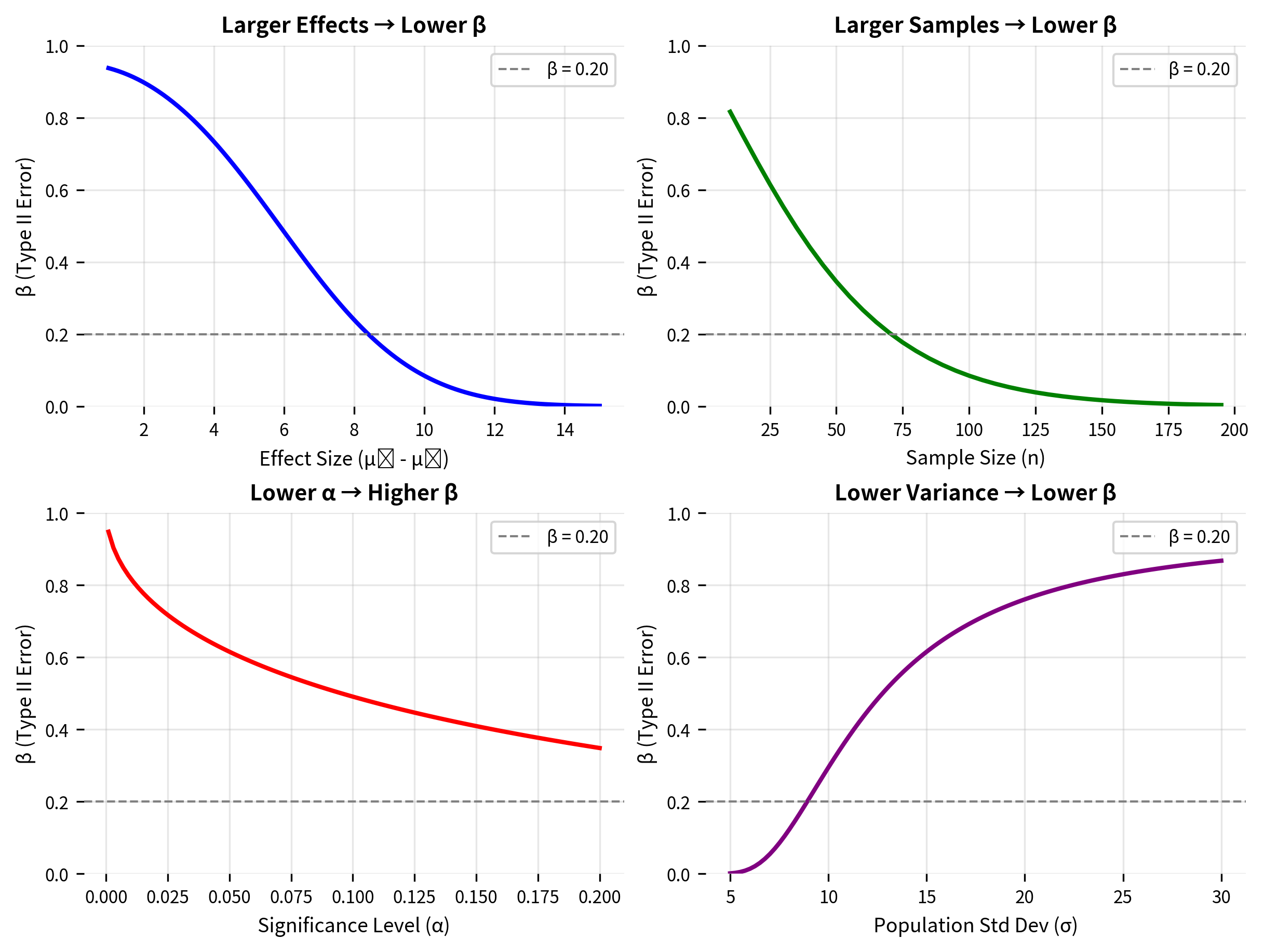

The Type II error probability depends on four interrelated factors:

1. Effect size: The larger the true effect (the distance between and ), the smaller β becomes. Larger effects are easier to detect because the alternative distribution is further from the null distribution.

2. Sample size: Larger samples decrease β. More data reduces the standard error , making both distributions narrower and easier to distinguish.

3. Significance level: Lower α means higher β, all else equal. Making it harder to reject (requiring more extreme evidence) also makes it harder to detect true effects.

4. Population variability: Lower population variance (smaller σ) decreases β. Less noise means the signal is easier to detect.

Real-World Consequences of Type II Errors

Type II errors represent missed opportunities and can have serious consequences:

Medical diagnosis: A patient with early-stage cancer is told their screening test is negative. The cancer continues to grow undetected, potentially reaching a stage where treatment is less effective.

Drug development: A pharmaceutical company abandons a drug that would actually be effective because their clinical trial failed to show a statistically significant benefit. Patients are deprived of a treatment that could help them.

Safety testing: An engineer fails to detect that a structural component is weaker than specifications require. The component is used in construction, potentially leading to failure under stress.

Criminal justice: A guilty person is acquitted due to insufficient evidence. While this is preferred to convicting the innocent, it still represents a failure of the justice system to hold offenders accountable.

Research: A scientist fails to detect a genuine relationship in their data. The discovery is delayed or never made, slowing scientific progress.

Statistical Power: 1 - β

Statistical power is defined as : the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis. If β is the probability of a Type II error (missing a real effect), then power is the probability of detecting that real effect.

Why Power Matters

Power tells you how sensitive your study is. If a genuine effect exists, power gives the probability that your study will find it:

- 80% power: 80% chance of detecting a true effect, 20% chance of missing it

- 50% power: Essentially a coin flip: you're as likely to miss the effect as to find it

- 20% power: You'll miss the effect 80% of the time: your study is almost useless

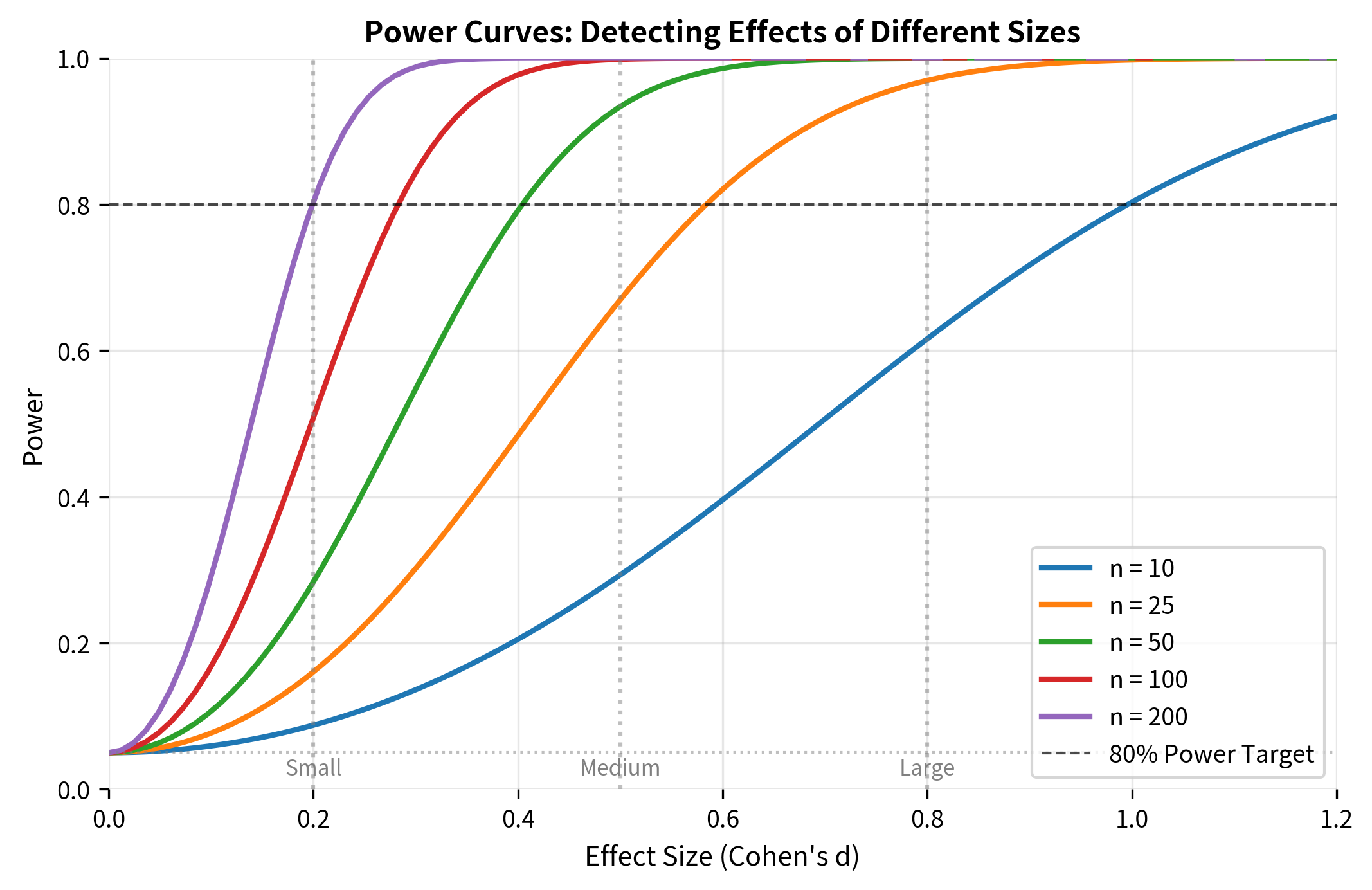

The conventional target is 80% power (β = 0.20). This means accepting a 1-in-5 chance of missing a real effect, which is considered an acceptable tradeoff in most research contexts. Some fields, particularly confirmatory research or high-stakes decisions, target 90% power.

Power Curves

A power curve shows how power varies with effect size for a given sample size and significance level. These curves are essential for understanding what effects your study can detect.

The Problem of Underpowered Studies

Underpowered studies are one of the most serious problems in research. When a study lacks sufficient power:

-

True effects are missed: The study is likely to produce a non-significant result even when a real effect exists.

-

Significant results are exaggerated: If an underpowered study does find significance, the effect size estimate is likely to be inflated (the "winner's curse").

-

Non-significant results are misinterpreted: Researchers may incorrectly conclude that "there is no effect" when the study simply lacked the power to detect it.

-

Resources are wasted: Time, money, and participant effort go into studies that cannot answer the research question.

-

Publication bias is amplified: Only the "lucky" underpowered studies that happen to achieve significance get published, leading to a distorted literature.

This simulation demonstrates the winner's curse: when underpowered studies do achieve significance, they systematically overestimate the true effect size. This happens because only the "lucky" samples, those with upward random fluctuations, cross the significance threshold.

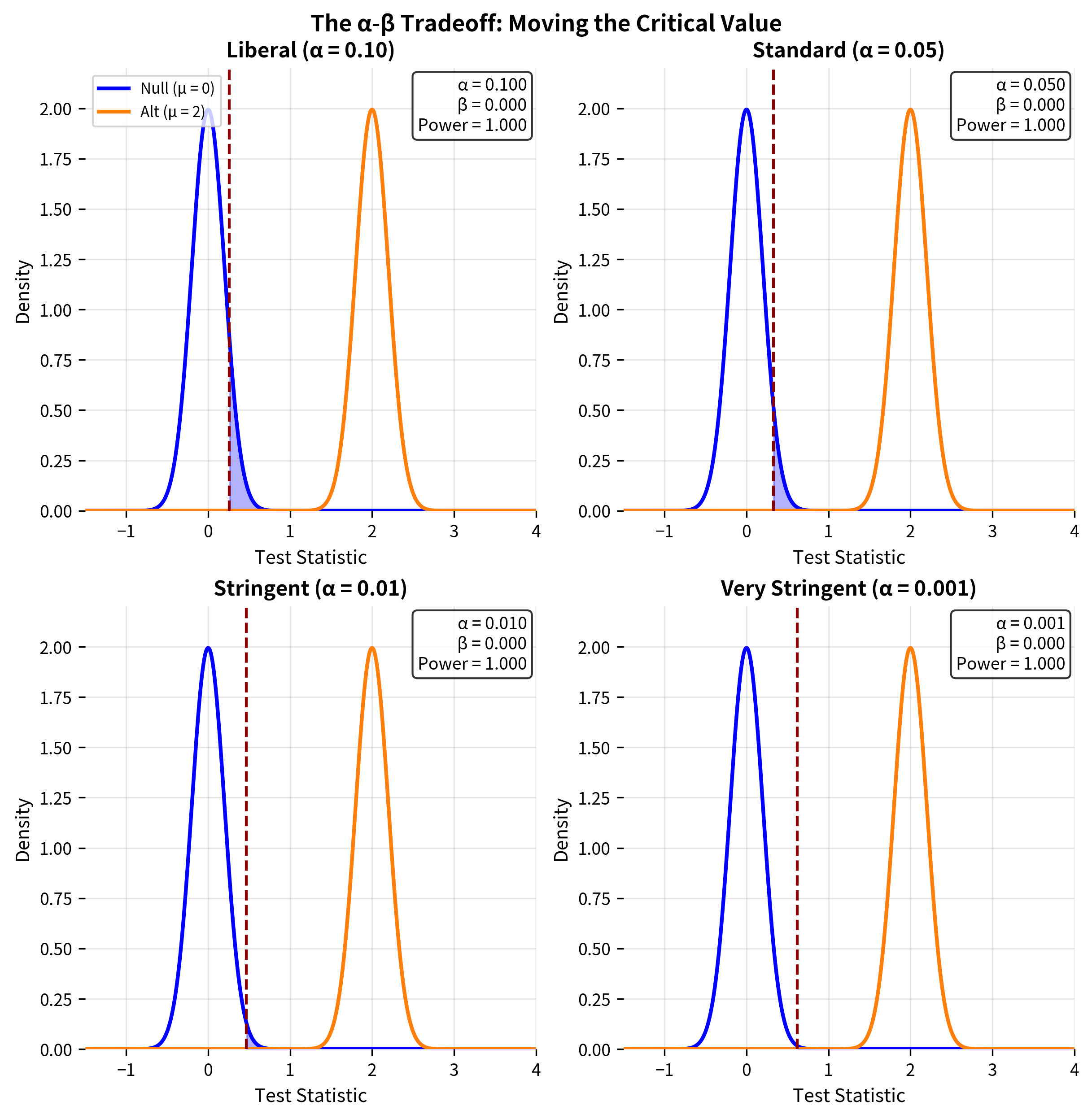

The Fundamental Tradeoff

For a fixed sample size, there is an inevitable tradeoff between Type I and Type II errors. Decreasing α (being more stringent about false positives) necessarily increases β (making false negatives more likely), and vice versa.

This tradeoff is best visualized by showing both distributions, the null and the alternative, and seeing how the critical value divides the space.

Managing the Tradeoff

Given this tradeoff, how should you balance Type I and Type II errors? The answer depends on the relative costs of each error type in your specific context.

Framework for Choosing α:

Consider what happens if you make each type of error:

| If Type I Error is... | And Type II Error is... | Then... |

|---|---|---|

| Very costly | Less costly | Use lower α (0.01 or lower) |

| Less costly | Very costly | Use higher α (0.10) and ensure adequate power |

| Equally costly | Equally costly | Use conventional α (0.05) |

Examples of Context-Dependent Decisions:

-

Criminal trial: Type I error (convicting innocent) is considered much worse than Type II error (acquitting guilty). This is why "beyond reasonable doubt" sets a very high bar, effectively using a very low α.

-

Medical screening: For a deadly but treatable disease, Type II error (missing cases) may be worse than Type I error (false alarms that lead to follow-up testing). A higher α might be appropriate.

-

Drug approval: Both errors are costly: approving ineffective drugs (Type I) wastes resources and exposes patients to side effects, while rejecting effective drugs (Type II) denies patients beneficial treatments. The FDA's approach is to use stringent α but also require adequate sample sizes for power.

-

Particle physics: Claiming a new particle discovery that is actually noise would be extremely embarrassing and wasteful. The 5-sigma standard (α ≈ 3 × 10⁻⁷) reflects the high cost of Type I errors in this field.

Putting It All Together: A Worked Example

Let's work through a complete example that ties together all the concepts.

Scenario: A pharmaceutical company is testing whether a new drug reduces blood pressure more than the current standard treatment. They need to design a study that balances both error types appropriately.

Decision Framework for the Example

Based on this analysis, the pharmaceutical company can make an informed decision:

Summary

Type I and Type II errors are the two ways hypothesis tests can fail. Understanding them is essential for designing studies and interpreting results:

Type I Error (α): Rejecting a true null hypothesis, a false positive. You conclude an effect exists when it doesn't.

- Probability equals your chosen significance level

- You control α directly by your choice of significance threshold

- Consequences: wasted resources, false claims, harm from unnecessary interventions

Type II Error (β): Failing to reject a false null hypothesis, a false negative. You miss a real effect.

- Probability depends on effect size, sample size, significance level, and population variance

- You influence β through study design, primarily sample size

- Consequences: missed discoveries, failed treatments, wasted research effort

Power (1 - β): The probability of correctly detecting a true effect.

- Conventional target: 80% (β = 0.20)

- Higher power requires larger samples, larger effects, or higher α

- Underpowered studies are one of the most serious problems in research

The Fundamental Tradeoff: For a fixed sample size, decreasing α increases β. The only way to reduce both simultaneously is to increase the sample size.

The key insight is that these error rates are not just abstract probabilities: they have real consequences for patients, businesses, and scientific progress. Thoughtful study design requires explicitly considering these tradeoffs in the context of your specific application.

What's Next

Understanding error types prepares you for power analysis and sample size determination. In the next section, you'll learn how to calculate the sample size needed to detect effects of a given size with a specified probability. This involves:

- Setting power targets based on the consequences of Type II errors

- Calculating minimum detectable effects for given sample sizes

- Understanding the relationship between effect size, sample size, and power

- Using power analysis software and formulas

You'll also explore effect sizes in depth: standardized measures of the magnitude of effects that are independent of sample size. Effect sizes are essential for interpreting results and for meta-analysis, where results from multiple studies are combined. Finally, you'll learn about multiple comparisons, where conducting many tests inflates the overall Type I error rate and requires special correction methods.

These concepts build directly on the error framework you've learned here. Every statistical decision involves weighing the risks of Type I and Type II errors—the tools in upcoming sections will help you make these decisions systematically.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about Type I and Type II errors.

Comments