Discover how chain-of-thought reasoning emerges in large language models. Learn CoT prompting techniques, scaling behavior, and self-consistency methods.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Chain-of-Thought Emergence

In the previous chapter, we explored how in-context learning emerges as models scale beyond certain compute thresholds. Chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning represents perhaps the most striking example of emergent capability: the ability of language models to solve complex problems by generating intermediate reasoning steps before producing a final answer. This chapter examines how CoT was discovered, the conditions under which it emerges, techniques for eliciting it, and current theories about the mechanisms underlying this remarkable behavior.

The discovery of chain-of-thought prompting fundamentally changed how we interact with large language models. Before CoT, models often failed at multi-step reasoning tasks even when they possessed the knowledge needed to solve them. A model might know that a store sells apples for $2 each and that someone has $10, yet fail to correctly answer how many apples they can buy. The key insight was that prompting models to "show their work" could unlock reasoning capabilities that were latent but inaccessible through direct questioning.

The Discovery of Chain-of-Thought

Chain-of-thought prompting was systematically studied by Wei et al. (2022), though researchers had observed similar phenomena informally. The core finding was deceptively simple yet highly significant: including step-by-step reasoning examples in the prompt causes models to generate their own intermediate reasoning steps, dramatically improving performance on tasks requiring multi-step inference. This discovery revealed that the barrier to complex reasoning wasn't necessarily the model's lack of capability, but rather our failure to communicate effectively with these systems about how we wanted them to approach problems.

To understand why this matters, consider how humans naturally solve complex problems. We don't typically leap directly from question to answer. Instead, we break problems into manageable pieces, work through each piece systematically, and combine our intermediate results. A student solving a word problem writes out their calculations. A detective articulates their reasoning before reaching a conclusion. Chain-of-thought prompting essentially teaches language models to adopt this same structured approach.

Consider a standard arithmetic word problem that illustrates the challenge:

Roger has 5 tennis balls. He buys 2 more cans of tennis balls. Each can has 3 balls. How many tennis balls does he have now?

A model prompted with just the question might output "11" directly, with no explanation. Often this answer would be wrong. The model might say "10" by confusing the number of cans with the total balls purchased, or "8" by only partially accounting for the original balls. The problem isn't that the model lacks knowledge of arithmetic or the meaning of the words. Rather, the model struggles to orchestrate its knowledge into the correct sequence of operations when asked to produce an immediate answer.

But when shown examples where each step is made explicit, something remarkable happens:

Roger has 5 tennis balls. He buys 2 more cans of tennis balls. Each can has 3 balls. How many tennis balls does he have now?

Roger started with 5 balls. 2 cans at 3 balls each is 6 balls. 5 + 6 = 11. The answer is 11.

The model learns to generate similar reasoning chains for new problems, and its accuracy improves substantially. By seeing that the appropriate response format involves articulating intermediate calculations, the model begins to produce its own step-by-step reasoning when faced with novel questions.

What makes this genuinely surprising is that no one explicitly trained these models to reason step-by-step. Standard language model pretraining involves predicting the next token on text from the internet, books, and other corpora. The training objective is simply to become better at predicting what word comes next. There's no explicit reward signal for logical reasoning or mathematical accuracy. Yet somewhere in this process, models acquire the ability to decompose problems and work through them sequentially, a capability that only manifests when properly prompted. The reasoning ability appears to be learned implicitly, as a byproduct of exposure to human text that contains explanations, derivations, and worked solutions.

Initial Observations

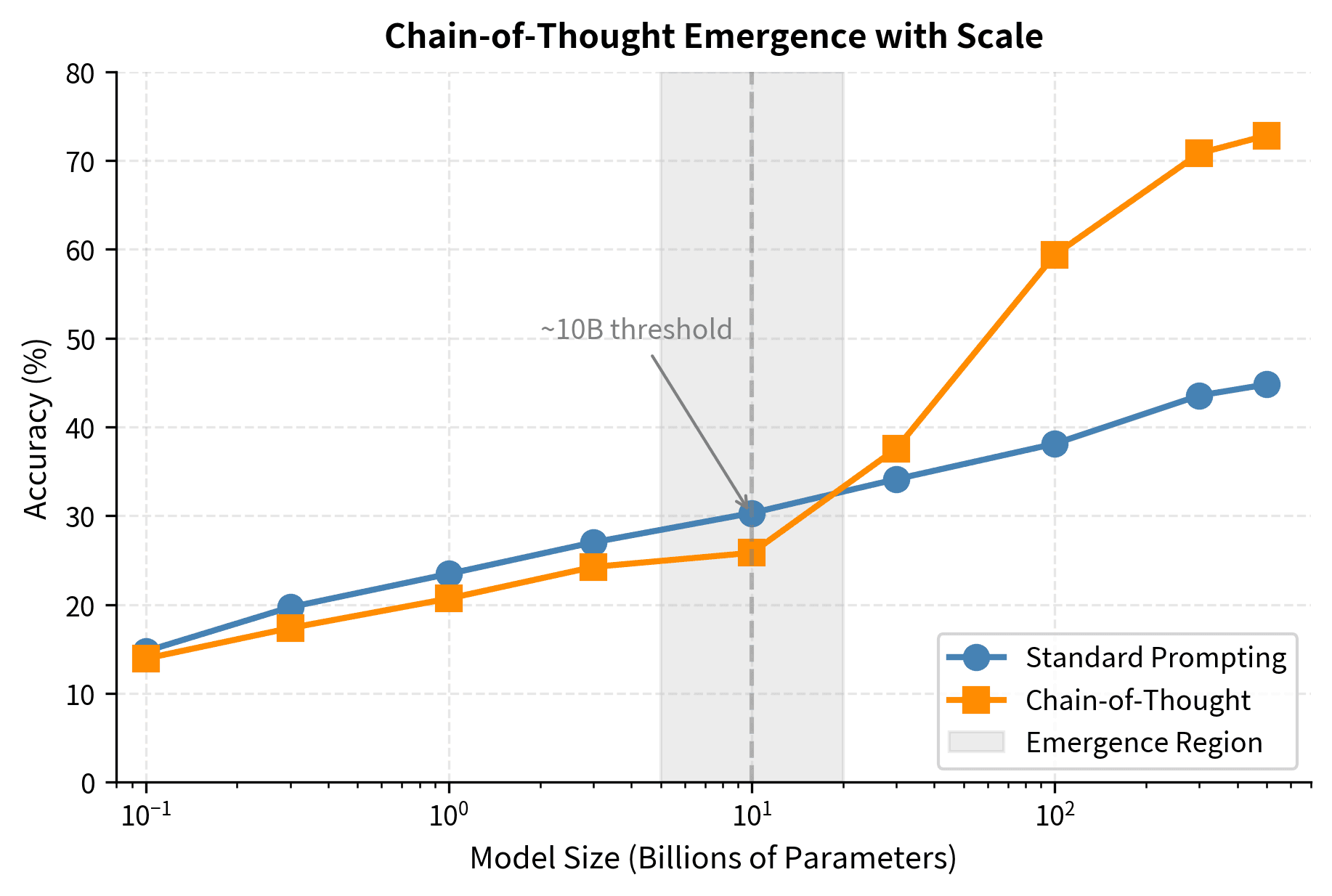

The original observations about CoT emergence came from several key findings that together painted a picture of a genuinely novel capability. First, smaller models showed no improvement (or even degradation) when prompted with chain-of-thought examples. Models with fewer than approximately 10 billion parameters often produced incoherent reasoning chains or simply ignored the demonstration format entirely. When smaller models attempted to generate reasoning steps, the results were frequently nonsensical: steps that did not follow logically from each other, arithmetic operations applied incorrectly, or conclusions that bore no relationship to the preceding "reasoning." This was not just poor performance. It was qualitatively different from what larger models produced.

Second, large models showed dramatic improvements that exceeded what anyone had anticipated. PaLM 540B achieved 57.1% accuracy on the GSM8K math benchmark with CoT prompting compared to just 17.9% with with standard prompting, a more than threefold improvement from the same model using the same knowledge, differing only in how the question was posed. This improvement wasn't a modest gain that might be attributed to noise or lucky prompt engineering; it represented a fundamental shift in the model's apparent capabilities.

Third, the reasoning chains themselves were often (though not always) logically coherent and human-interpretable. Models were not just producing word salad that happened to precede correct answers; they were generating valid intermediate steps that a human could follow and verify. Each step typically followed from the previous one, arithmetic operations were usually applied correctly, and the logical structure of the argument was sound. This interpretability meant that when models made errors, researchers could often identify exactly where the reasoning went wrong. This transparency is something direct answers cannot provide.

A prompting technique where the model is encouraged to generate intermediate reasoning steps before producing a final answer. This can be achieved through few-shot examples containing reasoning traces or through zero-shot prompts like "Let's think step by step." The technique works by activating the model's learned patterns of systematic reasoning discourse, shifting it from a "give me the answer" mode to a "show your work" mode.

The phase transition aspect was striking and connects to important questions about how capabilities develop in neural networks. As we discussed in the chapter on emergence in neural networks, emergent capabilities often appear suddenly at certain scale thresholds rather than improving gradually. CoT reasoning follows this pattern with remarkable clarity: models below a critical size gain nothing from chain-of-thought prompting, while models above this threshold show substantial benefits. The transition isn't gradual. There's a relatively narrow band of model sizes where CoT effectiveness goes from essentially zero to dramatically positive.

Chain-of-Thought Elicitation

Researchers have developed multiple techniques for eliciting chain-of-thought reasoning from language models. Each approach offers different tradeoffs between effectiveness, generality, and prompt engineering effort. Understanding these techniques is essential for practitioners who want to apply CoT reasoning effectively, as the choice of elicitation method can significantly impact both the quality of reasoning and the practical costs of deployment.

Few-Shot Chain-of-Thought

The original approach involves providing exemplars that demonstrate the reasoning process. This builds directly on the in-context learning capabilities we discussed in the previous chapter, leveraging the model's ability to recognize and continue patterns it observes in its input context. The prompt structure typically follows this pattern:

Q: [Question 1]

A: [Step-by-step reasoning for question 1]. The answer is [answer 1].

Q: [Question 2]

A: [Step-by-step reasoning for question 2]. The answer is [answer 2].

Q: [New question]

A:

The model learns from the demonstrations that it should generate intermediate steps before the final answer. This learning happens entirely through pattern recognition. The model observes that questions in this context are followed by explanatory text, not just bare answers, and it generalizes this pattern to new questions. The quality of the reasoning chains in the exemplars matters significantly. Demonstrations with clear, logical steps tend to produce better results than those with convoluted or incorrect reasoning. If the examples contain sloppy reasoning, skipped steps, or errors, the model may reproduce these flaws in its own generations.

Few-shot CoT requires careful exemplar selection. This represents both its main strength and its primary burden. The demonstrations should cover the types of reasoning required for the target task, but they need not be from the same domain. Research has shown that exemplars from math problems can improve reasoning on logical puzzles, and vice versa. This cross-domain transfer suggests that CoT elicitation activates general reasoning capabilities rather than task-specific knowledge. The model isn't learning "how to solve math problems" from the examples. It's learning "when presented with questions in this format, produce step-by-step reasoning rather than jumping to conclusions."

The generality of few-shot CoT comes at the cost of prompt engineering effort. Crafting high-quality exemplars requires understanding both the task and what constitutes good reasoning for that task. Poor exemplar choices can undermine performance, and the optimal number and type of examples varies by task and model.

Zero-Shot Chain-of-Thought

Kojima et al. (2022) discovered that a remarkably simple prompt addition could elicit chain-of-thought reasoning without any demonstrations whatsoever. Simply appending "Let's think step by step" to a question causes models to generate reasoning chains. This discovery was surprising because it suggested that the reasoning capability existed within the model and merely needed the right trigger to activate, requiring no examples.

This zero-shot approach works because models have seen phrases like "let's think step by step" in their training data. These phrases are often followed by detailed explanations. Academic papers, textbooks, tutorial videos, and forum posts frequently use such phrases as preambles to methodical explanations. During pretraining, the model learned that this phrase predicts a particular style of subsequent text: careful, sequential, explanatory. The prompt acts as a trigger, activating the model's learned association between this phrase and systematic reasoning.

The effectiveness of zero-shot CoT varies by task and model. For some problems, it approaches the performance of carefully crafted few-shot prompts, achieving results that seem remarkable given the minimal prompt engineering required. For others, particularly those requiring domain-specific reasoning patterns or unusual problem structures, few-shot demonstrations remain superior because they can communicate task-specific conventions that the generic trigger cannot.

The advantage of zero-shot CoT lies in its simplicity and universal applicability: no exemplar construction is required, making it easy to apply across diverse tasks without domain expertise. A practitioner can add "Let's think step by step" to any question and potentially improve reasoning quality, without needing to understand the task deeply enough to craft good examples.

Other trigger phrases have been explored:

- "Take a deep breath and work through this step by step"

- "Let me work through this carefully"

- "I need to break this down" These phrases all leverage the model's training on human problem-solving discourse. Such phrases commonly precede methodical analysis. The variety of effective triggers supports the view that CoT activation is about shifting the model into an "explanation mode" rather than about any specific phrase's magical properties.

Self-Consistency Decoding

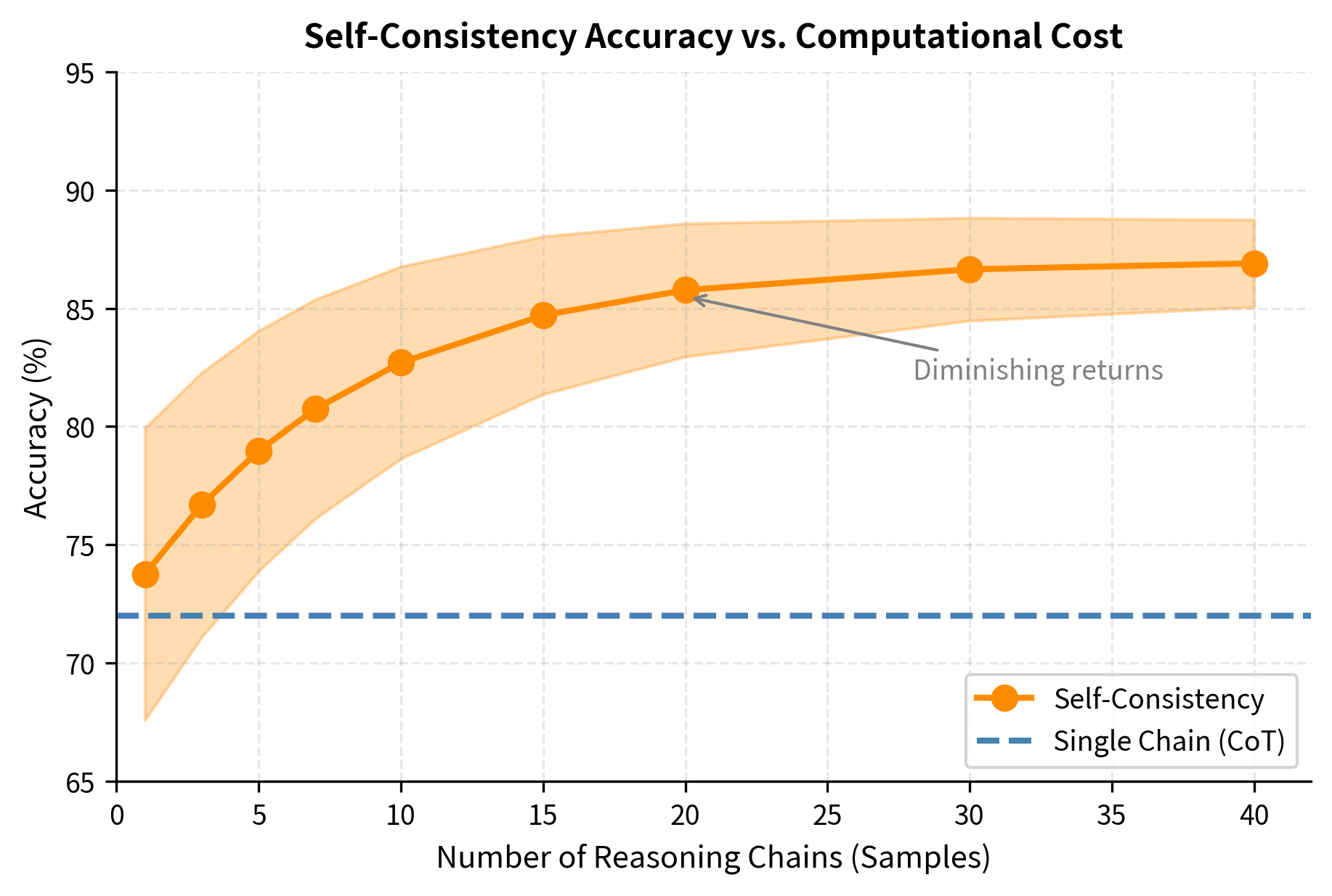

Wang et al. (2022) proposed an enhancement to chain-of-thought prompting called self-consistency that addresses a fundamental limitation of single-chain generation. Rather than generating a single reasoning chain, the model produces multiple independent chains by sampling with temperature. The final answer is determined by majority voting across all generated answers.

The intuition behind self-consistency is straightforward. Correct reasoning processes are more likely to converge on the same answer because truth is constrained: there's typically one right answer, and valid reasoning paths must arrive at it. Errors, by contrast, introduce variance and idiosyncrasy. A model might add instead of multiply in one chain, misread a number in another, or skip a step in a third, leading to different wrong answers. If five reasoning chains produce the answer "42" and two produce "38," we can be more confident that "42" is correct because the agreement suggests these chains found the constrained path to the true answer.

Self-consistency works because different reasoning paths can arrive at the same correct answer through genuinely different approaches. A math problem might be solved by working forward from the given information or backward from the goal; an arithmetic calculation might be decomposed in multiple valid orders. These alternative paths provide independent verification. Meanwhile, errors tend to be idiosyncratic because they depend on which specific mistake was made. A model might make an arithmetic mistake in one chain but not another, or choose different valid approaches that nevertheless converge on the same answer.

This approach significantly improves performance but increases inference cost linearly with the number of samples. Generating five chains costs five times as much as generating one. This tradeoff must be evaluated in context. For high-stakes applications where accuracy is paramount, the additional cost may be well justified; for high-volume, low-stakes applications, single-chain generation may be more appropriate.

Least-to-Most Prompting

For problems requiring extended reasoning with many steps, least-to-most prompting decomposes the task hierarchically rather than asking the model to tackle everything at once. First, the model breaks the problem into subproblems, explicitly identifying what intermediate questions need to be answered. Then it solves each subproblem in order, with solutions to earlier subproblems included in the context for later ones.

This two-phase approach addresses a key limitation of standard CoT: for very complex problems, even large models struggle to maintain coherent reasoning across many steps when they must plan and execute simultaneously. By separating the planning phase (identifying subproblems) from the execution phase (solving them), least-to-most prompting reduces the cognitive load at each step.

This approach is particularly effective for tasks with compositional structure, where the answer to the full problem can be built systematically from answers to simpler components. Mathematical proof naturally decomposes into lemmas; multi-hop question answering requires establishing intermediate facts; program synthesis builds complex functions from simpler ones. In all these cases, least-to-most prompting provides a scaffold that guides the model through the problem's inherent structure.

Scaling Behavior of Chain-of-Thought

The relationship between model scale and chain-of-thought effectiveness reveals important insights about how reasoning capabilities develop in language models. Understanding this relationship is crucial both for practitioners deciding when to use CoT and for researchers seeking to understand the nature of reasoning in neural networks.

The Scale Threshold

Empirical studies consistently find that chain-of-thought prompting provides no benefit, and often hurts performance, for models below approximately 10 billion parameters. This threshold isn't sharp (representing a region where CoT effectiveness transitions from absent to present), but it's remarkably consistent across different model families, training approaches, and benchmark tasks. The existence of this threshold suggests something fundamental about what's required for coherent multi-step reasoning.

Below the threshold, smaller models prompted with chain-of-thought examples often produce malformed reasoning chains that reveal the absence of genuine reasoning capability. They might repeat steps mechanically without advancing toward a solution. They might generate non sequiturs, statements that have no logical connection to what came before. Or they might produce text that resembles reasoning in surface form but lacks logical coherence, using mathematical symbols and reasoning words without applying them correctly. The model has learned to mimic the format of step-by-step reasoning from its training data without having developed the underlying capability to reason correctly.

At and above the threshold, models begin producing coherent chains with valid intermediate steps. The transition is qualitative, not just quantitative. It's not that larger models reason slightly better; it's that they reason in a fundamentally different way. The quality of reasoning continues to improve with scale even above the threshold; larger models make fewer logical errors, handle more complex reasoning patterns, and generalize better to novel problem types. But the crucial transition is from incoherent to coherent, and this happens within a relatively narrow band of model sizes.

Performance Curves

The scaling behavior of CoT can be understood by comparing performance curves across model sizes for different prompting strategies. These curves reveal the distinctive nature of chain-of-thought as an emergent capability.

For standard (non-CoT) prompting, performance typically increases smoothly with log model size, following patterns consistent with the scaling laws we discussed earlier. The curve rises gradually and shows no sudden transitions. A model twice as large is somewhat better, and a model ten times as large is noticeably better, but the improvement is continuous and predictable.

With chain-of-thought prompting, the curve has a dramatically different shape. Below the threshold, CoT performance matches or falls below standard prompting. The additional reasoning steps provide no benefit and may introduce confusion or errors. Above the threshold, CoT performance rises steeply, often surpassing what would be predicted by simple extrapolation of the standard prompting curve. The gap between standard and CoT performance widens as models grow larger, meaning that CoT becomes increasingly valuable as models scale up.

This divergence suggests that CoT prompting doesn't just amplify existing capabilities in a straightforward way; it unlocks qualitatively different processing that becomes available at scale. The reasoning circuits activated by CoT appear to develop only in sufficiently large models, and once present, they enable a different mode of problem-solving that continues to improve with further scaling.

Why Does Scale Matter?

Several hypotheses explain why chain-of-thought reasoning requires scale, each highlighting different aspects of what makes multi-step reasoning computationally demanding.

Knowledge integration:

Multi-step reasoning requires combining multiple pieces of knowledge (mathematical facts, logical rules, and world knowledge) in sequence. A model solving a word problem must know arithmetic operations, understand the semantics of words like "each" and "total," recognize the structure of the problem, and apply all of this knowledge in the correct order. Larger models have greater capacity to store and integrate knowledge, allowing them to bring more relevant information to bear on each step. A model must know both that multiplication precedes addition and the specific multiplication facts needed, then apply both correctly in sequence, a coordination problem that requires substantial representational capacity.

Context tracking:

Reasoning chains require maintaining state across many tokens. The model must remember earlier computed values (like "the total cost is $15"), track what has and hasn't been established ("we know the price per item but haven't yet calculated the quantity"), and maintain coherence over extended generation. This is essentially a working memory task, and the representational capacity in larger models may enable more robust context tracking. With more parameters devoted to processing the context, models can maintain more accurate representations of what has been computed and what remains to be done.

Compositional generalization:

Reasoning often requires applying known operations in novel combinations. A model might have seen problems involving division and problems involving subtraction, but never a problem requiring subtraction followed by division with the result. Larger models appear to develop more modular, composable representations that support this generalization. They can chain operations they've seen separately into sequences they haven't encountered in training. This compositional capability seems to require scale to develop robustly.

Error accumulation:

Each step in a reasoning chain can introduce errors, whether in arithmetic, logic, or interpretation. Longer chains accumulate more errors unless each step is highly accurate. If each step has 95% accuracy, a ten-step chain has only about 60% accuracy (). Larger models make fewer per-step errors, allowing them to maintain accuracy across longer chains. This error reduction compounds multiplicatively over the length of the reasoning chain, making scale increasingly valuable for complex problems.

Mechanistic Theories

Understanding why chain-of-thought works requires moving beyond behavioral observations to examine what's happening inside the model. This investigation connects observable improvements in reasoning to underlying computational mechanisms. Several theoretical frameworks attempt to explain the phenomenon, each offering different insights into the nature of reasoning in neural networks.

The Computation Extension Hypothesis

One explanation views the reasoning chain as extending the model's computation by providing additional processing steps. A transformer processes its input through a fixed number of layers, typically dozens of attention and feedforward layers applied sequentially. Each forward pass through the network represents a fixed amount of computation, regardless of problem complexity. When the model generates each output token, it performs another forward pass, effectively increasing its computational depth.

By producing intermediate tokens, the model gains additional forward passes, with the results of earlier computations made available via the context for subsequent steps. Consider a problem that requires 10 sequential reasoning steps, meaning 10 distinct pieces of computation that must happen in order, each depending on the results of the previous. With direct answering, the model must compress all 10 steps into a single forward pass through its fixed architecture. This is like asking someone to solve a problem entirely in their head without writing anything down. With chain-of-thought, each step can be computed in a separate forward pass, with the result externalized as text and made available for the next step.

This hypothesis explains why longer, more detailed reasoning chains sometimes improve performance: they provide more intermediate computation, more opportunities for the model to process and refine its understanding. It also explains why CoT helps more for complex problems requiring many steps than for simple problems solvable in few steps. The benefit of additional computation scales with how much computation is actually needed.

However, this explanation has important limitations. Not all additional tokens improve reasoning. Generating irrelevant steps or padding (text that does not advance the solution) does not help and may hurt by consuming context window space and potentially confusing subsequent processing. The model must generate useful intermediate steps, which requires knowing what computation to perform at each step. The computation extension hypothesis explains why intermediate steps can help but not how the model knows which steps to generate.

The Scratchpad Hypothesis

Related to computation extension, the scratchpad hypothesis emphasizes that intermediate tokens serve as external memory, creating a written record that persists and can be referenced. The model's internal state, including its hidden representations and attention patterns, is limited in capacity and transient. But text in the context window persists and can be attended to in later steps, providing a form of external memory.

When a model writes "2 cans at 3 balls each is 6 balls," it has offloaded the result "6" to the context where it remains accessible throughout all subsequent generation. Without this externalization, the result would need to be maintained in internal representations, which may be unreliable or capacity-limited. The model's internal memory for carrying numerical results across many tokens of generation is imperfect; writing the result down sidesteps this limitation.

This view suggests that chain-of-thought helps most when problems require maintaining intermediate results that would otherwise be lost. This includes problems where you need to compute something, hold onto it, compute something else, and then combine the results. Empirically, CoT provides larger gains on problems with more intermediate values to track, supporting this hypothesis. A problem requiring tracking five separate quantities benefits more from CoT than one requiring tracking only a single value.

The scratchpad hypothesis also explains why certain formats of chain-of-thought are more effective than others. Explicitly labeling intermediate results ("total cost = $15") makes them easier to retrieve later than burying them in prose. The scratchpad is only useful if its contents are organized for easy access.

The Format Matching Hypothesis

Another perspective focuses on training data and the patterns the model has learned to associate with certain contexts. During pretraining, models encounter many examples of step-by-step reasoning: mathematics textbooks working through problems, programming tutorials explaining code line by line, and explanatory articles building up to conclusions. When prompted with chain-of-thought examples, models may simply be doing what they've learned: continuing the pattern of reasoning discourse they've seen countless times in training.

This hypothesis explains why CoT prompting can be elicited with phrases like "let's think step by step." These phrases frequently precede detailed reasoning in the training data, creating a learned association. When the model encounters such a phrase, it recognizes a context where reasoning is appropriate and likely. Under this view, the model isn't discovering how to reason at inference time. It's recognizing a context where reasoning behavior is expected based on patterns in its training.

The format matching view implies that the quality of CoT reasoning is bounded by the quality of reasoning in training data. If the training corpus contains incorrect or confused reasoning (which it certainly does, alongside correct reasoning), models may reproduce those patterns. Indeed, CoT reasoning in current models often exhibits systematic errors that reflect common human mistakes: confusing correlation with causation, making sign errors in arithmetic, or drawing conclusions that don't fully follow from premises. These errors appear not because the model lacks knowledge, but because it learned from human text that contains such errors.

The Emergent Algorithm Hypothesis

A more speculative view proposes that sufficiently large transformers can learn to implement general-purpose algorithms through their weights, not just statistical patterns but genuine computational procedures. Specific patterns of reasoning may be encoded as learned subroutines that activate when appropriate prompts are given. These patterns include decomposition of problems into parts, case analysis for handling different conditions, and recursive problem-solving for nested structures.

Under this view, CoT prompting doesn't create reasoning capability but accesses already-learned algorithmic modules that exist within the model's parameters. The reasoning algorithms developed during pretraining on massive text corpora. These corpora contain many implicit examples of problem-solving strategies embedded in worked examples, explanations, and discussions. Through exposure to millions of instances of human reasoning, the model distilled something like general reasoning procedures.

Recent mechanistic interpretability work has identified specific attention patterns and MLP activations associated with particular reasoning operations, providing some support for this view. Researchers have found "induction heads" that copy patterns, circuits that perform comparison operations, and specialized processing for numerical quantities. However, a complete characterization of "reasoning circuits" in transformers remains an open research challenge. We can identify pieces of the puzzle, but the full picture of how transformers implement reasoning algorithmically remains elusive.

Worked Example: Analyzing Chain-of-Thought Behavior

Let's examine in detail how chain-of-thought affects model outputs on a specific problem that requires multi-step reasoning. This concrete example will illustrate the principles we've discussed and reveal both the power and the mechanics of chain-of-thought prompting.

Problem: A bookstore sells notebooks for $3 each. Maria has $20. She wants to buy as many notebooks as she can and still have at least $5 left for lunch. How many notebooks can Maria buy?

This problem requires understanding a constraint (keeping money for lunch), computing the available budget, and then performing division. All these pieces must be correctly integrated. Let's see how different prompting approaches handle it.

Standard Prompting Response (hypothetical from smaller model):

6 notebooks

This answer is incorrect. The model appears to have divided 20 by 3, getting approximately 6.67, and rounded down without considering the lunch money constraint. The constraint was either ignored or lost in the compressed computation that produced the direct answer. We cannot know from this response why the model got it wrong. Did it not understand the constraint? Did it understand but fail to apply it? The opacity of direct answering makes diagnosis impossible.

Chain-of-Thought Response (from larger model):

Maria has $20 total. She needs to keep at least $5 for lunch. So she can spend at most $20 - $5 = $15 on notebooks. Each notebook costs $3. $15 ÷ $3 = 5 notebooks. Maria can buy 5 notebooks.

The chain-of-thought response correctly identifies the constraint (keeping $5 for lunch), computes the available budget ($15), and performs the division to get the correct answer (5 notebooks). Each step is visible, verifiable, and logically connected to the next.

What makes this work? The explicit intermediate steps force the model to represent each part of the problem distinctly. The constraint that might be lost in direct computation is explicitly stated in the second line and used in the third. Each arithmetic operation is isolated and visible, making errors easier to catch and correct. The model's "thinking" is exposed to us and, perhaps more importantly, to itself. Each written step becomes part of the context for generating the next step.

This example also illustrates the debugging advantage of chain-of-thought. If a model produced an incorrect CoT response, we could examine the chain to identify where reasoning went wrong. Was the constraint understood but misapplied? Was the subtraction correct but the division wrong? This transparency is impossible with direct answers, and it is valuable for understanding model behavior and improving prompts.

Code Implementation

Let's implement chain-of-thought prompting and compare it with standard prompting across several examples. These implementations will demonstrate the practical mechanics of CoT and provide tools for exploring its behavior empirically.

We'll create test problems that require multi-step reasoning, each involving different combinations of arithmetic operations and constraints:

Now let's compare standard prompting with chain-of-thought. The standard prompt asks only for the final answer, while the CoT prompt explicitly requests step-by-step reasoning:

The chain-of-thought responses reveal the model's reasoning process in ways that direct answers cannot. When errors occur, we can often identify exactly where the reasoning went wrong. This is something impossible with direct answers. The explicit intermediate steps make the model's computation transparent and debuggable, allowing us to verify each logical transition and identify systematic patterns in errors. This transparency is valuable not just for understanding individual responses but for improving prompts and identifying model limitations.

Let's implement self-consistency decoding, which generates multiple reasoning chains and uses majority voting. This approach trades computational cost for improved accuracy and provides a measure of confidence in the final answer:

Self-consistency provides not just an answer but also a confidence measure that reflects the model's internal agreement. A confidence score near 100% indicates strong agreement across reasoning chains, suggesting the model consistently arrives at the same answer through different reasoning paths. This agreement is evidence that the answer is robust, as multiple independent approaches converged on it. Lower confidence scores reveal problems where the model's reasoning is unstable or where multiple plausible interpretations exist. This vote distribution serves as a valuable diagnostic. When chains disagree, examining the individual reasoning traces can reveal where different approaches diverge, whether through ambiguity in the problem or through errors that affect some chains but not others.

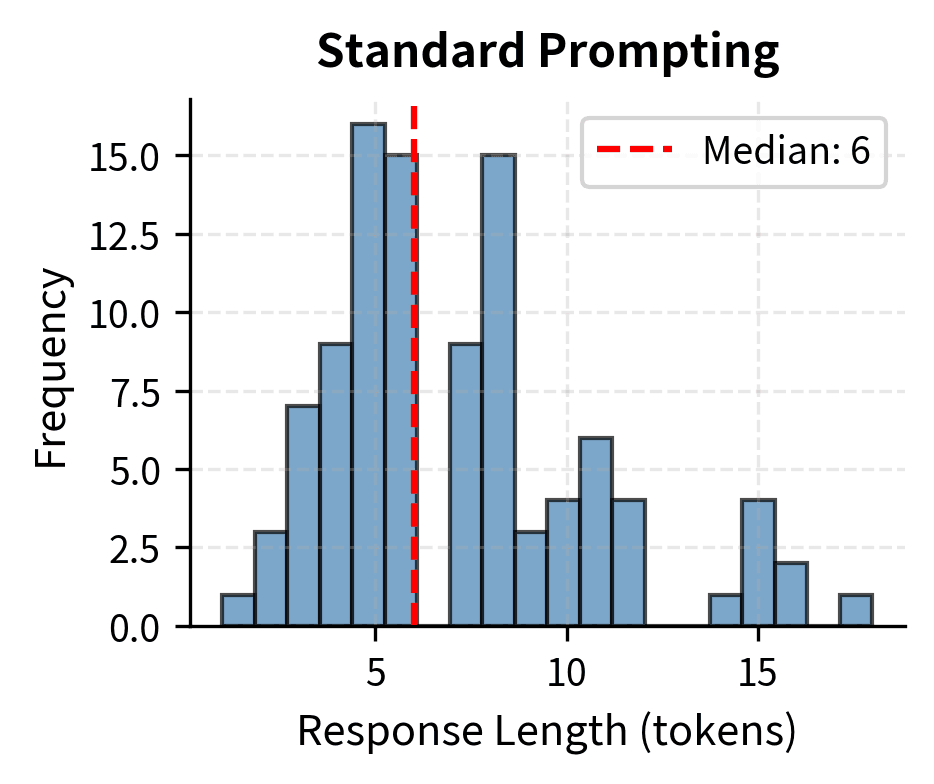

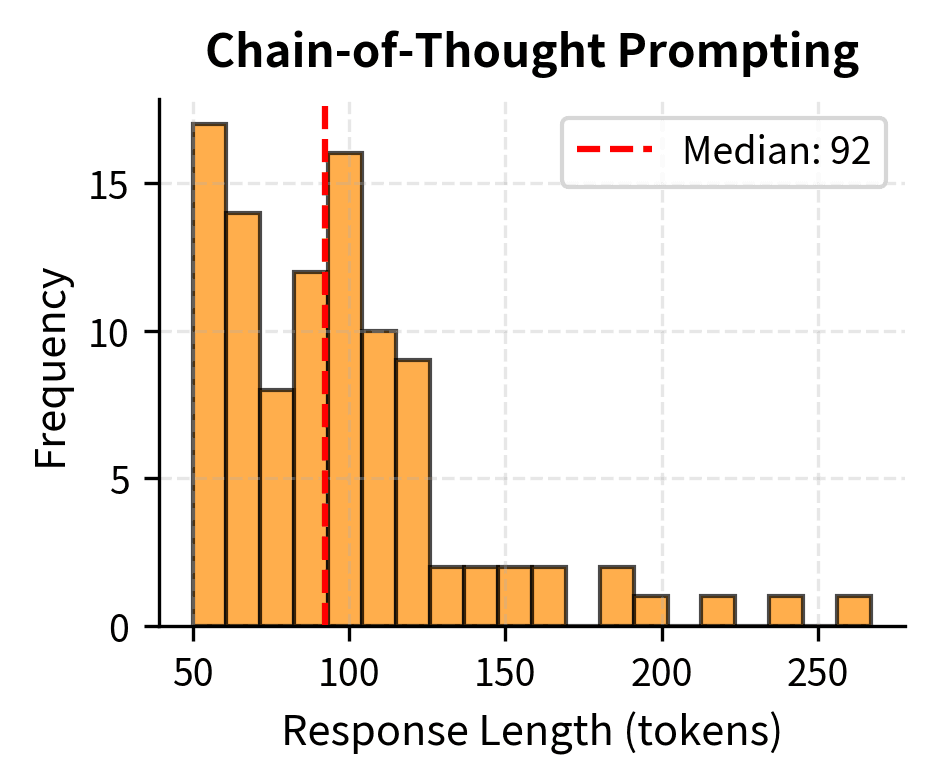

Let's visualize how chain-of-thought prompting affects token generation patterns. The difference in response length between standard and CoT prompting reflects the fundamental tradeoff between computational cost and reasoning depth.

The length difference reflects a fundamental tradeoff that practitioners must navigate. CoT uses more tokens (and thus more compute) to achieve better accuracy. Standard prompting responses cluster tightly around short lengths (median ~7 tokens), containing only the final numerical answer with no supporting explanation. Chain-of-thought responses are roughly 10-15 times longer (median ~90 tokens), reflecting the explicit reasoning steps generated before the answer. This token overhead translates directly to increased API costs and latency, making the choice between prompting strategies an engineering decision that balances accuracy requirements against computational budgets. For applications where every response is critical, the extra cost is worthwhile. For high-volume applications where occasional errors are tolerable, the efficiency of direct prompting may be preferable.

Limitations and Practical Implications

Despite its effectiveness, chain-of-thought reasoning has significant limitations that constrain its applicability.

Faithfulness Problems

A key limitation is the question of whether generated reasoning chains actually reflect the model's internal computation. A model might produce a chain that reads as logical justification but bears no relationship to how it actually arrived at its answer. Research has found cases where models generate plausible-looking but incorrect reasoning that happens to lead to correct answers, and conversely, correct reasoning that leads to wrong answers due to final-step errors.

This "faithfulness" problem has significant implications. If we cannot trust that the reasoning chain represents the model's actual computation, we cannot use CoT for interpretability or debugging. A model might appear to reason correctly while actually relying on spurious correlations or memorized patterns. Current techniques cannot reliably distinguish faithful from post-hoc rationalization in model-generated reasoning.

Propagation of Errors

While chain-of-thought can reduce errors on problems where direct computation fails, it introduces new failure modes. Errors in early reasoning steps propagate to later steps, potentially amplifying small mistakes into completely wrong answers. A single arithmetic error early in a chain invalidates all subsequent computation, even if those steps are individually correct.

Self-consistency mitigates this by sampling multiple chains but at significant compute cost. For applications requiring high reliability, even self-consistency may not provide adequate guarantees. The fundamental issue is that transformer-based language models were not designed for precise symbolic computation and remain error-prone even with chain-of-thought scaffolding.

Domain Limitations

Chain-of-thought prompting helps most on problems that can be decomposed into sequential steps expressible in natural language. This includes many math problems, logical puzzles, and multi-hop reasoning tasks. However, some cognitive tasks do not naturally decompose this way. Pattern recognition, creative generation, and tasks requiring holistic evaluation may not benefit from step-by-step reasoning, and forcing decomposition can actually harm performance.

Additionally, the quality of CoT reasoning depends on the model having relevant knowledge and skills. A model cannot reason correctly about quantum physics if it lacks the relevant knowledge, no matter how well prompted. Chain-of-thought enhances reasoning with existing knowledge; it cannot substitute for missing knowledge.

Computational Overhead

Chain-of-thought responses are substantially longer than direct answers, typically 10-15 times longer for multi-step problems. This increases both latency and cost in production settings. Self-consistency multiplies this overhead by the number of samples generated. For applications processing many queries or requiring real-time responses, CoT may be impractical despite its accuracy benefits.

The overhead motivates research into "compressed" chain-of-thought, where models learn to reason with fewer tokens, and into distillation approaches that transfer CoT capabilities to smaller models. We'll explore some of these approaches in later chapters when we discuss inference scaling and efficiency techniques.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for chain-of-thought prompting and self-consistency are:

- temperature: Controls randomness in generation. Use

temperature=0for deterministic CoT responses, ortemperature=0.7for self-consistency sampling where diversity is needed. - max_tokens: Maximum response length. CoT requires more tokens than direct answers, typically 200-500 tokens for multi-step problems.

- n_samples: Number of reasoning chains for self-consistency. More samples increase accuracy but multiply inference cost linearly.

- model: The language model to use. Larger models (>10B parameters) benefit from CoT while smaller models may not show improvement.

Summary

Chain-of-thought reasoning is one of the most significant emergent capabilities in large language models. By prompting models to generate intermediate reasoning steps, we can unlock problem-solving abilities that remain inaccessible through direct questioning.

The key insights from this chapter include:

-

Scale threshold: CoT benefits emerge only in models above approximately 10 billion parameters. Below this threshold, models produce incoherent reasoning chains that provide no benefit.

-

Multiple elicitation methods: Few-shot demonstrations, zero-shot triggers like "let's think step by step," and ensemble methods like self-consistency all enable CoT reasoning with different tradeoffs.

-

Computation extension: The primary mechanism appears to be that intermediate tokens extend the model's effective computation, allowing it to solve problems requiring more sequential steps than a single forward pass permits.

-

Faithfulness concerns: Generated reasoning chains may not reflect actual internal computation. This limits the reliability of CoT for interpretability and verification.

-

Task dependency: CoT helps most on problems with clear decomposition into sequential steps. Not all tasks benefit, and some may be harmed by forced decomposition.

The emergence of chain-of-thought reasoning raises questions about the nature of reasoning in neural networks. Are these models truly reasoning, or merely producing text that mimics reasoning? The next chapter examines how our choice of metrics affects whether capabilities appear emergent, shedding light on this question from a measurement perspective. Later, when we explore inference-time scaling techniques, we'll return to chain-of-thought as a foundation for more sophisticated reasoning approaches.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about chain-of-thought emergence in large language models.

Comments