Master document chunking for RAG systems. Explore fixed-size, recursive, and semantic strategies to balance retrieval precision with context window limits.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Document Chunking

In the previous chapters, we built up the core RAG pipeline: retrieving relevant documents and using them to ground an LLM's responses. But we glossed over a critical question: what exactly constitutes a "document" in retrieval? A single PDF might contain hundreds of pages. A webpage might span thousands of words. If you embed an entire document as one vector, the resulting embedding must compress an enormous amount of information into a single point in vector space. Important details get diluted, and retrieval precision suffers.

Document chunking solves this problem by splitting large documents into smaller, self-contained pieces before embedding and indexing them. The choice of chunking strategy, chunk size, and overlap between chunks has a surprisingly large impact on RAG quality. A poorly chunked document can bury relevant information inside irrelevant context, while a well-chunked document surfaces precisely the passage you need.

This chapter explores the landscape of chunking strategies, from simple fixed-size splits to semantically aware approaches that respect the natural structure of text. We will implement each strategy, examine how chunk size affects retrieval, and build intuition for when to use each approach.

Why Chunking Matters

To understand why chunking is so important, consider what happens during the retrieval stage of RAG. As we discussed in the Dense Retrieval chapter, we encode both queries and documents into dense vectors and retrieve documents whose embeddings are closest to the query embedding. The quality of this retrieval depends directly on how well each embedding captures the meaning of its text. If the embedding is a faithful representation of a focused, coherent passage, it will match queries about that passage with high confidence. If the embedding is a blurred summary of many disparate topics, it becomes a mediocre match for all of them and a strong match for none.

Embedding models have two fundamental constraints that make chunking necessary:

- context window limits: Most embedding models have a maximum input length, typically 512 tokens for models like those in the BERT family and up to 8,192 tokens for newer models. Text beyond this limit is simply truncated and lost. This means that if you feed a 10,000-token document into a 512-token embedding model, nearly 95% of the document is silently discarded. The resulting embedding reflects only the opening passage, leaving the vast majority of the document completely unrepresented in your index.

- Information density: Even within the context window, longer texts produce embeddings that represent a blend of all topics covered. A 5,000-word article about climate change might discuss ocean temperatures, carbon emissions, policy proposals, and economic impacts. A single embedding for this article would be a vague average of all these topics, matching none of them precisely. Think of this like trying to describe an entire meal with a single adjective: "savory" might loosely apply to the soup, the steak, and the roasted vegetables, but it captures the distinctive character of none of them.

Chunking addresses both constraints simultaneously. By splitting documents into smaller pieces, each chunk fits within the model's context window and covers a focused topic. When you ask about ocean temperature trends, the chunk specifically discussing that topic will produce a much stronger similarity match than the full article's embedding would. The key insight is that retrieval quality is not just about having the right information somewhere in your index; it is about having that information represented in a way that makes it discoverable. Chunking is the mechanism that creates this discoverability. Each chunk becomes a distinct, findable unit in vector space, carrying a focused semantic signal that can resonate with a matching query.

Chunking is not just a preprocessing step; it defines the fundamental unit of retrieval. When you chunk a document, you are deciding the granularity at which information can be found and returned. Too coarse, and relevant details are buried in noise. Too fine, and context is lost. This decision echoes throughout the entire pipeline: it shapes what the embedding model encodes, what the similarity search can find, and what the LLM ultimately sees in its context window.

Fixed-Size Chunking

The simplest chunking strategy splits text into pieces of a fixed number of characters or tokens, regardless of where sentences or paragraphs begin or end. Despite its simplicity, fixed-size chunking is surprisingly common in production RAG systems because it is fast, predictable, and easy to reason about. When you need to process millions of documents quickly and you want deterministic, reproducible behavior, fixed-size chunking is often the pragmatic choice. Its uniformity also simplifies downstream engineering: every chunk consumes roughly the same amount of storage, embedding compute, and retrieval bandwidth.

Character-Based Splitting

The most basic approach splits text every characters. This produces chunks of uniform length but can cut words and sentences in the middle. The logic is straightforward: start at position 0, take the next characters, advance the starting position, and repeat until the entire text is consumed. When overlap is specified, the starting position advances by fewer than characters, causing adjacent chunks to share some trailing and leading text.

Notice how chunks cut through words and sentences without regard for meaning. Chunk 1 might start in the middle of a word, making it difficult for an embedding model to capture the intended meaning. A phrase like "approximately 10 percent of all species" could be severed into "approxi" at the end of one chunk and "mately 10 percent of all species" at the beginning of the next, rendering both fragments less semantically coherent than the original sentence. This is the fundamental weakness of character-based splitting: it optimizes for uniform size at the expense of coherence. The embedding model must then try to extract meaning from text that may begin or end mid-thought, producing embeddings that are noisier and less representative of any single idea.

Token-Based Splitting

A better variant splits by token count rather than character count. Since embedding models operate on tokens, not raw characters, this ensures each chunk uses the model's capacity efficiently. A character-based chunk of 200 characters might translate to anywhere from 30 to 60 tokens depending on word length and vocabulary, creating unpredictable utilization of the embedding model's context window. Token-based splitting eliminates this variability by directly controlling the unit that matters. We can use the tiktoken library, which implements the tokenizers used by OpenAI models, to perform this conversion accurately.

Token-based splitting guarantees each chunk uses a predictable number of tokens, but it still does not respect sentence boundaries. A sentence split across two chunks loses coherence in both. The first chunk ends with an incomplete thought, and the second begins without the context established earlier in the sentence. For many retrieval scenarios, this partial-sentence problem degrades embedding quality enough to motivate the sentence-aware approaches we explore next.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for fixed-size chunking are:

- chunk_size: The target size of each chunk (in characters or tokens). Smaller chunks are more precise, while larger chunks provide more context. This parameter directly controls the trade-off between retrieval granularity and the amount of information each chunk carries.

- overlap: The number of units (characters or tokens) repeated between adjacent chunks to prevent information loss at boundaries. Overlap acts as a safety net, ensuring that content near a cut point is fully represented in at least one chunk. We explore this concept in depth in the Chunk Overlap section below.

Sentence-Based Chunking

A more linguistically motivated approach uses sentence boundaries as the atomic unit. As we covered in the Sentence Segmentation chapter, identifying sentence boundaries is itself a non-trivial task that must handle abbreviations, decimal numbers, and other edge cases. Here, we leverage spaCy's sentence segmentation for robust boundary detection.

The idea is simple but powerful: split the text into individual sentences first, then group consecutive sentences together into chunks until adding the next sentence would exceed the desired size limit. By treating sentences as indivisible building blocks, this approach guarantees that no chunk will ever contain a partial sentence. Every chunk begins at the start of a sentence and ends at the conclusion of one, preserving the grammatical and semantic completeness that embedding models rely on.

Each chunk now contains complete sentences. The text within each chunk is coherent, making it much easier for an embedding model to capture its meaning. When the model processes a sentence-aligned chunk, it encounters grammatically well-formed text with clear subjects, verbs, and objects, exactly the kind of input it was trained on. This alignment between the structure of training data and the structure of your chunks tends to produce higher-quality embeddings. The chunk sizes are no longer perfectly uniform, since they depend on sentence lengths, but this is a worthwhile trade-off. A chunk that is 180 characters of coherent prose will almost always produce a better embedding than a chunk that is exactly 200 characters but begins with the fragment "tion efforts are critical to preserving."

Key Parameters

The key parameters for sentence-based chunking are:

- max_chunk_size: The maximum length (in characters or tokens) allowed for a chunk before a split is forced. Sentences are accumulated into the current chunk as long as this limit is not exceeded, so actual chunk sizes will vary depending on where the sentence boundaries fall relative to this ceiling.

- overlap_sentences: The number of full sentences to repeat at the beginning of the next chunk to preserve context. Unlike character or token overlap, sentence overlap guarantees that the shared content is always a complete, meaningful unit. This is particularly valuable when consecutive sentences contain co-references ("This process..." or "These results...") that would be difficult to interpret without the preceding sentence.

Recursive Chunking

Real documents have hierarchical structure: sections, subsections, paragraphs, sentences, and words. Recursive chunking exploits this structure by attempting to split at the most meaningful boundary possible. The strategy embodies a simple but effective principle: always prefer splitting at the highest-level boundary that still produces chunks within the size limit. It tries a sequence of separators in order of decreasing granularity. If splitting by double newlines (paragraph boundaries) produces chunks that are small enough, it stops there. If not, it falls back to single newlines, then sentences, then words, then characters.

This layered approach means the algorithm naturally adapts to different parts of a document. A section with short paragraphs will be split along paragraph boundaries, preserving each paragraph as a self-contained unit. A section containing a single long paragraph will be split at sentence boundaries within that paragraph. Only as a last resort, when individual sentences exceed the chunk size limit, does the algorithm fall back to word-level or character-level splitting.

This approach is popularized by LangChain's RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter and is one of the most widely used strategies in practice. Its popularity stems from the fact that it produces reasonable results across a wide variety of document types without requiring any domain-specific configuration beyond the choice of separators.

Let's test it on a structured document with paragraphs:

The recursive approach respects paragraph boundaries when possible, falling back to finer-grained splits only when a paragraph exceeds the size limit. This preserves the document's logical structure in the chunks. The "Climate Change Overview" heading and its accompanying paragraph naturally form one chunk, while the "Impact on Ecosystems" section forms another. The algorithm arrives at these natural divisions not because it understands the content, but because the paragraph boundaries encoded by double newlines happen to align with topical boundaries, a pattern that holds reliably across well-structured documents.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for recursive chunking are:

- chunk_size: The hard limit on chunk size. The algorithm attempts to keep chunks under this limit while using the largest possible separators. This means the algorithm always prefers a paragraph-level split over a sentence-level split, as long as both produce chunks that fit within this budget.

- overlap: The number of characters to overlap between chunks. In recursive chunking, overlap is applied after the initial splitting pass, duplicating content from the end of one chunk into the beginning of the next.

- separators: An ordered list of strings used to split the text (e.g.,

["\n\n", "\n", " ", ""]). The algorithm tries them in sequence to find the best split point. The ordering is crucial: it encodes your preference for which types of boundaries should be preserved. By placing paragraph separators first, you ensure the algorithm only resorts to sentence or word breaks when paragraph-level splits are insufficient.

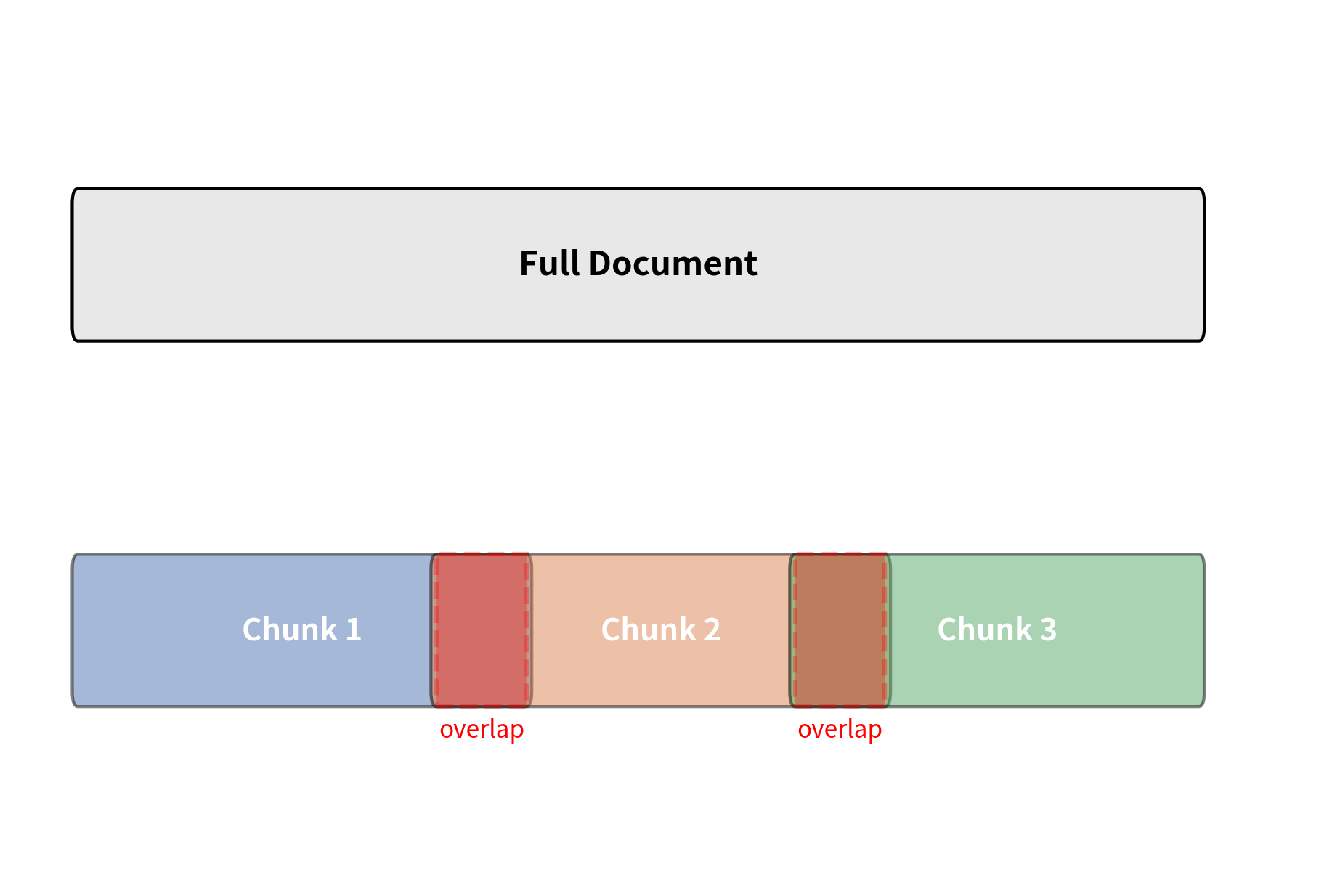

Chunk Overlap

When you split a document into non-overlapping chunks, information that spans a chunk boundary gets split across two chunks. A key fact might have its context in one chunk and its conclusion in the next. Neither chunk alone captures the complete idea, and retrieval may miss it entirely. Consider a passage where one sentence introduces a concept and the very next sentence provides the critical detail you are searching for. If the boundary falls between these two sentences, the first chunk contains a setup without a payoff, and the second chunk contains an answer without its question. An embedding of either chunk alone may fail to match your query.

Chunk overlap solves this by including some text from the end of each chunk at the beginning of the next. If your chunk size is 200 tokens and your overlap is 50 tokens, then the last 50 tokens of chunk appear again as the first 50 tokens of chunk . This means any passage of 50 or fewer tokens near the boundary is guaranteed to appear in full within at least one chunk. The overlapping region acts as a sliding window that "catches" boundary-spanning information, ensuring it is fully embedded in at least one vector.

The trade-off with overlap is straightforward:

- More overlap means better boundary coverage, but it increases the total number of chunks and storage requirements. It also means the same text appears in multiple embeddings, which can inflate retrieval results with near-duplicate chunks. If your query matches the overlapping region, both adjacent chunks will score highly, potentially consuming two of your top- retrieval slots with content that is largely redundant.

- Less overlap reduces redundancy, but risks losing context at boundaries. With zero overlap, any information that depends on content from both sides of a boundary is effectively invisible to retrieval.

A common rule of thumb is to set overlap to 10-20% of the chunk size. For a 500-token chunk, an overlap of 50-100 tokens usually provides sufficient boundary coverage without excessive duplication. This range represents a pragmatic balance: enough overlap to catch most boundary-spanning passages, but not so much that your index becomes bloated with near-identical chunks. In practice, if you find that retrieval frequently returns two highly similar chunks from adjacent positions in the same document, you may be using too much overlap. If you find that relevant answers are being missed because critical context lands on the wrong side of a boundary, you may need more.

Let's see overlap in action with our token-based chunker:

Compare the end of each chunk with the beginning of the next. You should see shared text that bridges the boundary, ensuring that any information near the cut point is captured in at least one chunk's embedding. This shared text is the overlap in action: it duplicates a small window of content so that the transition zone between chunks is always fully represented somewhere in the index.

Chunk Size Selection

Choosing the right chunk size is one of the most impactful decisions in a RAG pipeline. It involves a fundamental trade-off between precision and context, and the optimal balance depends on the nature of your data, the types of questions you ask, and the capabilities of your embedding model. Getting chunk size right can mean the difference between a system that reliably surfaces the perfect passage and one that returns vaguely related blocks of text.

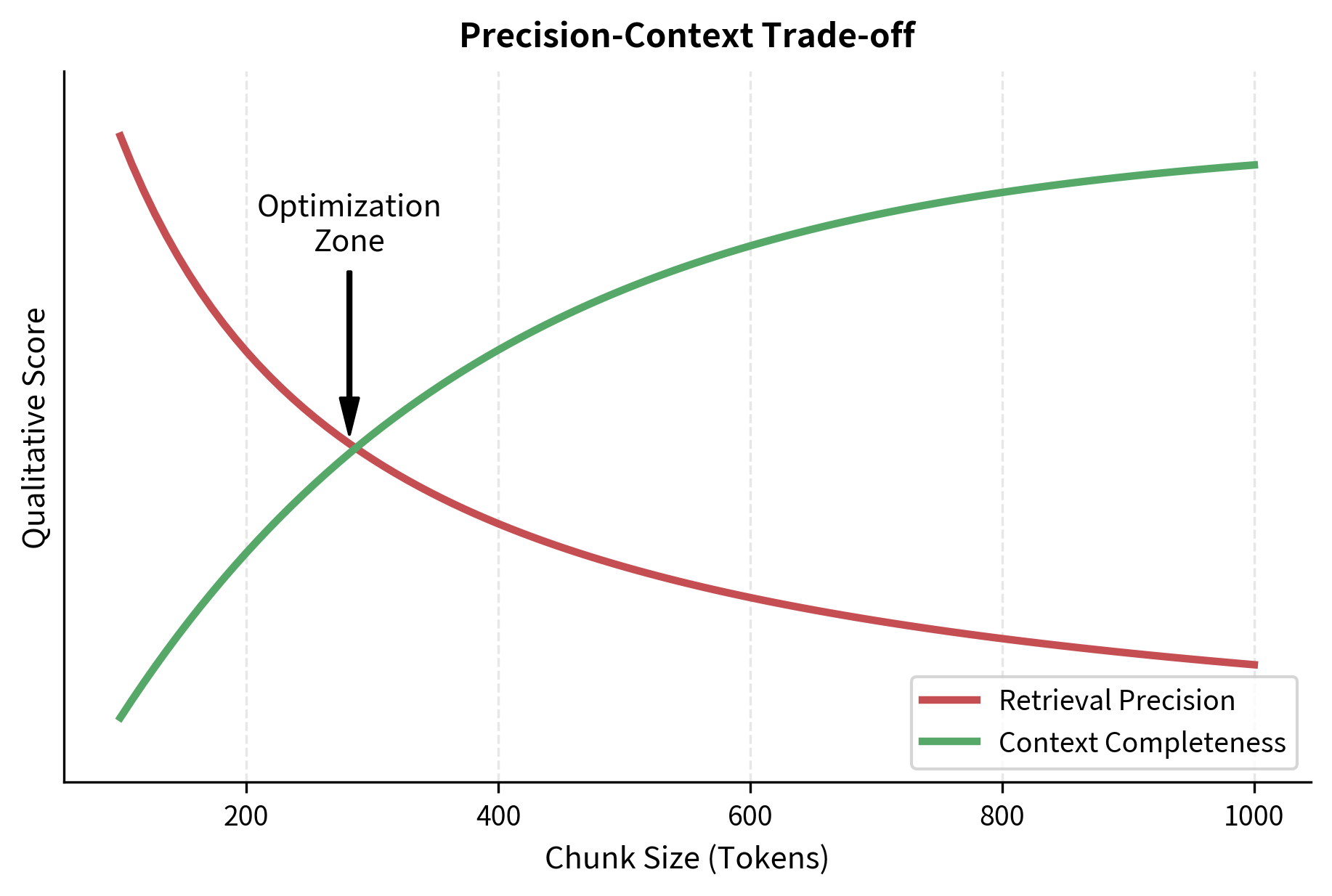

The Precision-Context Trade-off

The precision-context trade-off is the central tension in chunk size selection. At one extreme, you could make each chunk a single sentence, maximizing precision. At the other, you could embed entire documents, maximizing context. Neither extreme works well in practice, and understanding why illuminates the core challenge.

Small chunks (100-200 tokens) provide high retrieval precision. Each chunk covers a narrow topic, so when it matches a query, the match is likely relevant. The embedding vector represents a focused semantic concept, and the cosine similarity between query and chunk is a reliable indicator of topical alignment. However, small chunks may lack sufficient context for the LLM to generate a good answer. A chunk containing "The temperature was 42°C" is useless without knowing what system or location it refers to. The LLM receives a decontextualized fact and must either hallucinate the missing context or produce an unsatisfying response. Small chunks also increase the total number of chunks in your index, which raises storage and search costs.

Large chunks (500-1,000 tokens) provide rich context. The LLM receives enough surrounding information to understand and synthesize an answer. A paragraph that introduces a concept, provides evidence, and draws a conclusion gives the LLM everything it needs to produce a coherent response. But large chunks produce less precise embeddings because they cover more topics, and they may include irrelevant information that confuses the model. When a 800-token chunk discusses three related but distinct subtopics, its embedding becomes a centroid in the semantic space that lies between all three topics. A query that is specifically about one of those subtopics may find a better cosine similarity match with a more focused chunk from a completely different document. This dilution effect is the primary cost of large chunk sizes.

The optimal chunk size depends on several factors:

- Query type: Factoid questions ("What is the boiling point of water?") benefit from small chunks, while analytical questions ("Explain the causes of the 2008 financial crisis") need larger chunks with more context. If your application primarily serves one type of query, you can tune chunk size accordingly. If it serves a mix, you may need to compromise or use multiple chunk sizes.

- Document type: Technical documentation with short, self-contained sections works well with smaller chunks. Narrative text where ideas develop over paragraphs needs larger chunks. A software API reference, where each function's description is independent, naturally lends itself to small chunks. A legal brief, where arguments build across paragraphs, demands larger ones.

- Embedding model capacity: As we will explore in the next chapter on Embedding Models, different models have different optimal input lengths. Some models are trained on short passages and perform best with 1-2 sentences, while others handle full paragraphs effectively. Feeding a paragraph-optimized model a single sentence wastes its capacity, while feeding a sentence-optimized model a full paragraph may degrade its embedding quality.

Empirical Comparison

Let's compare how different chunk sizes affect the content of chunks from the same document. By viewing the same text through different chunk size lenses, we can build intuition for how this parameter shapes the granularity and coherence of the resulting pieces.

Smaller chunk sizes produce more chunks, each covering a narrower topic. With a 100-character limit, individual sentences or pairs of short sentences become the unit of retrieval, giving the system laser-like precision but very little surrounding context. Larger chunk sizes produce fewer chunks that span multiple topics: a 500-character chunk might combine the definition of supervised learning with examples of specific algorithms, creating a richer but less focused unit. There is no universally correct size; the right choice depends on your use case and should ideally be determined through evaluation, which we will cover in the RAG Evaluation chapter.

Structural Chunking

Many real-world documents have explicit structural markers: Markdown headers, HTML tags, LaTeX section commands, or table of contents entries. These markers are not arbitrary formatting; they represent deliberate authorial decisions about how information is organized. A section header signals a topical boundary, and the content beneath it forms a coherent unit that the author intended to be read together. Structural chunking uses these markers to split documents along their natural boundaries, ensuring each chunk corresponds to a coherent section or subsection.

This approach is particularly powerful for well-structured documents because it leverages organizational signals that other chunking methods ignore. A fixed-size chunker treats a Markdown header as just another line of text, potentially grouping it with the tail end of the previous section. A structural chunker recognizes it as a boundary, keeping each section intact and associated with its heading.

Notice how each chunk includes its header context (e.g., [Supervised Learning > Classification]). This metadata helps both the embedding model and the LLM understand the chunk's position within the document's hierarchy. A chunk about "Classification" without the context that it falls under "Supervised Learning" within a "Machine Learning" document would be less informative. The header path acts as a breadcrumb trail that disambiguates the content: "Classification" in a machine learning document means something very different from "Classification" in a library science document. By prepending this contextual path, the resulting embedding encodes not just what the chunk says, but where it sits within the larger knowledge structure.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for structural chunking are:

- max_chunk_size: The maximum size for the content of each structural section. If a section exceeds this, it is further split using a fallback strategy, typically sentence-based chunking within the section. This hybrid behavior is important because some documents contain sections that vary enormously in length: a brief introductory section might be a single sentence, while a detailed methodology section might span several pages. The fallback ensures that even oversized sections are chunked coherently, with each sub-chunk still carrying the parent section's header context.

Semantic Chunking

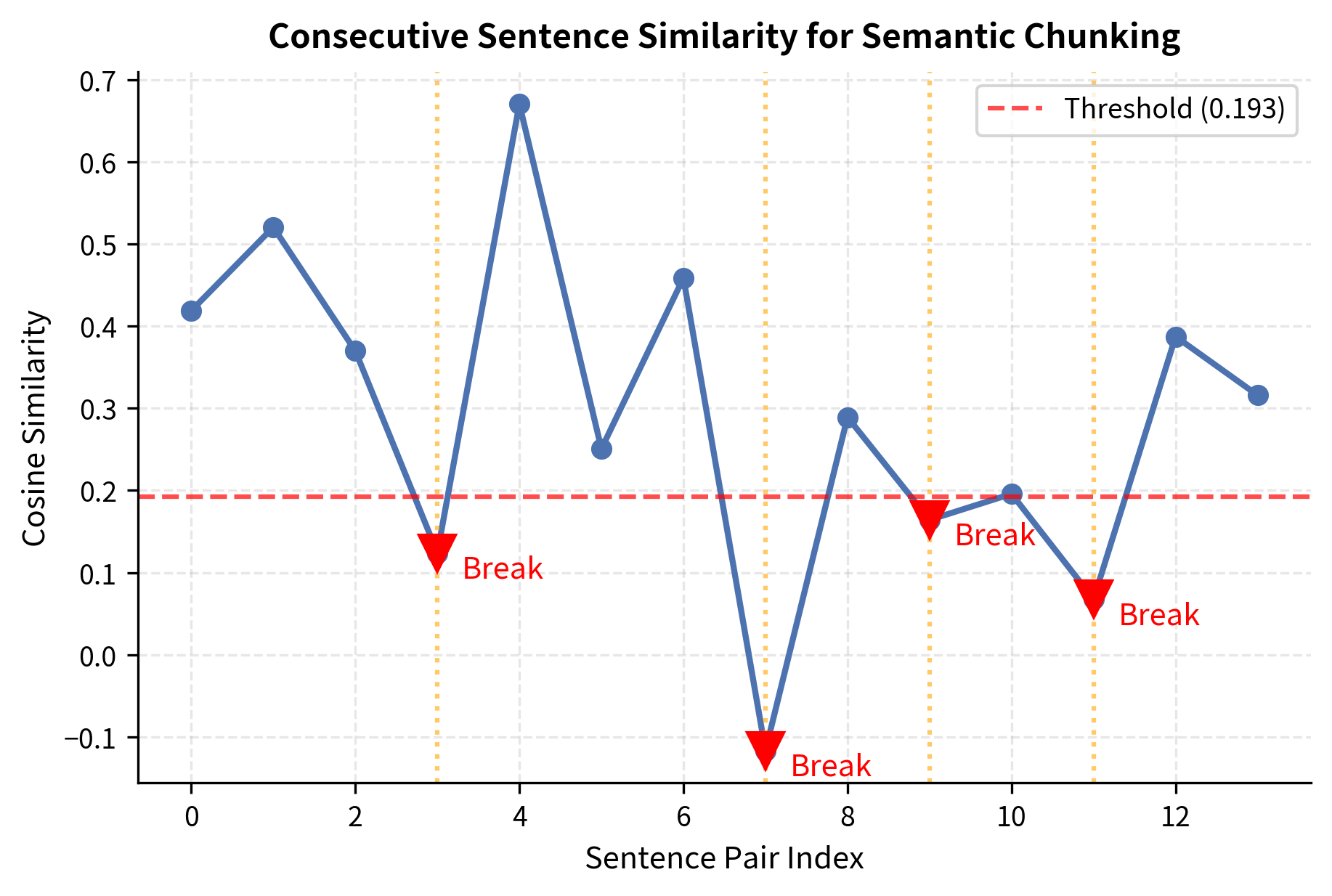

All the strategies we have discussed so far use surface-level cues: character counts, sentence boundaries, structural markers. None of them consider what the text actually means. A paragraph break might occur in the middle of a sustained argument, or two paragraphs separated by a heading might actually discuss the same topic from different angles. Surface-level chunking strategies are blind to these semantic realities. Semantic chunking addresses this by using embeddings to detect where topics shift within a document, and placing chunk boundaries at those transition points.

The core idea is elegant: if two consecutive sentences have similar embeddings, they likely discuss the same topic and should be in the same chunk. When embeddings diverge significantly between adjacent sentences, that point likely marks a topic shift and is a natural place to split. Rather than relying on formatting conventions that may or may not align with topical structure, semantic chunking directly measures the conceptual continuity of the text and uses that measurement to determine where to place boundaries.

Algorithm

The semantic chunking algorithm proceeds in four steps, each building naturally on the previous one. The first step decomposes the text into its atomic units. The second step captures the meaning of each unit. The third step measures how that meaning flows from one unit to the next. And the fourth step identifies the points where that flow is disrupted, signaling a topic transition.

- Segment text into sentences using standard sentence segmentation. Sentences serve as the finest-grained unit we consider, since splitting within a sentence would break grammatical coherence.

- Embed each sentence using a sentence embedding model. Each sentence is mapped to a dense vector that captures its semantic content. This gives us a sequence of vectors, one per sentence, representing the "meaning trajectory" of the document.

- Compute similarity between consecutive sentences using cosine similarity (as we discussed in the Dense Retrieval chapter). For each pair of adjacent sentences, we measure how closely related they are. A high similarity score means the two sentences discuss related content. A low score means the topic is shifting.

- Identify breakpoints where similarity drops below a threshold, or where the largest similarity drops occur. These breakpoints become the chunk boundaries. The text between consecutive breakpoints forms a single chunk, containing all the sentences that belong to one coherent topic.

Let's apply semantic chunking to a document that covers multiple distinct topics:

The semantic chunker detects topic transitions, placing boundaries between the astronomy, biology, and finance sections. Unlike fixed-size chunking, it produces chunks of varying length, each covering a coherent topic. Notice in particular that the document deliberately returns to astronomy in its final paragraph after the finance section. A structural chunker relying on paragraph breaks alone would separate all four paragraphs into distinct chunks without recognizing the thematic relationship between the first and last paragraphs. The semantic chunker, by contrast, detects the low similarity at the topic transitions, regardless of how the document is formatted.

Choosing the Threshold

The threshold parameter controls how aggressively the chunker splits. It determines the sensitivity of the algorithm to topic transitions: a lenient threshold ignores all but the most dramatic shifts, while a strict threshold reacts to even subtle changes in subject matter. A lower percentile (e.g., 10th) means only the most dramatic topic shifts trigger splits, producing larger, fewer chunks. A higher percentile (e.g., 50th) creates more, smaller chunks at every moderate topic change.

In practice, you can tune this using several approaches:

- Percentile-based thresholds (as above): Split at the -th percentile of similarity scores. This adapts to the document's overall coherence. A document where all consecutive sentences are highly related will have a higher threshold than one with naturally varied topics. This adaptivity is the key advantage: the algorithm calibrates itself to the document's baseline level of topical coherence, only splitting where coherence drops significantly relative to the document's own norm.

- Absolute thresholds: Split whenever similarity drops below a fixed value (e.g., 0.3). This is simpler but does not adapt to documents with generally high or low inter-sentence similarity. A technical paper with consistently high inter-sentence similarity might never trigger splits with an absolute threshold of 0.3, while a casual blog post with naturally varied topics might be split into tiny fragments.

- Standard deviation-based: Split when similarity drops more than one standard deviation below the mean. This captures statistically significant topic shifts. The logic mirrors outlier detection: if most sentence pairs have similarity around 0.7 with a standard deviation of 0.1, a pair with similarity 0.5 represents a meaningful departure from the norm and likely signals a genuine topic transition.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for the semantic chunking implementation are:

- threshold_percentile: Controls the sensitivity of split detection. Lower values (e.g., 10) trigger fewer splits, producing large chunks that may span loosely related subtopics. Higher values (e.g., 50) trigger more splits, producing smaller chunks that isolate finer-grained topics at the risk of fragmenting coherent discussions.

- min_chunk_size: Minimum number of sentences per chunk. Prevents creating tiny fragments from transient topic shifts. Without this constraint, a single transitional sentence that happens to differ from both its neighbors could be isolated into its own chunk, producing a fragment too small to be useful for retrieval or generation.

- model_name: The SentenceTransformer model used for embedding. Models with better semantic understanding produce more accurate boundaries. The choice of model matters because the similarity scores that drive splitting are only as good as the embeddings that produce them. A model with weak topical discrimination will produce noisy similarity curves that lead to poorly placed boundaries.

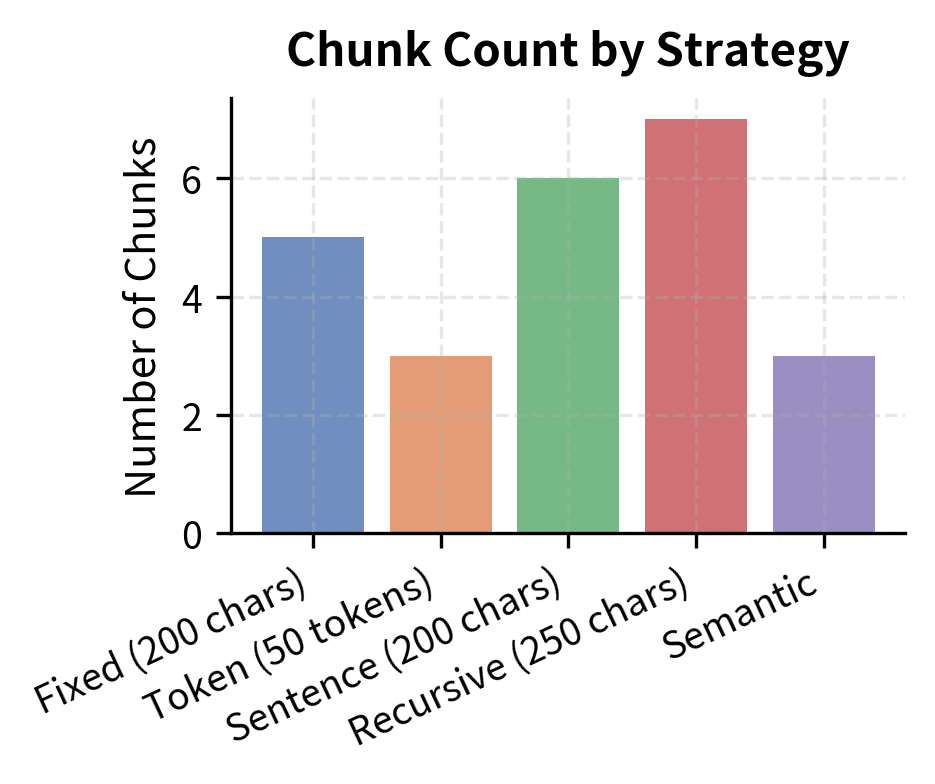

Comparing Chunking Strategies

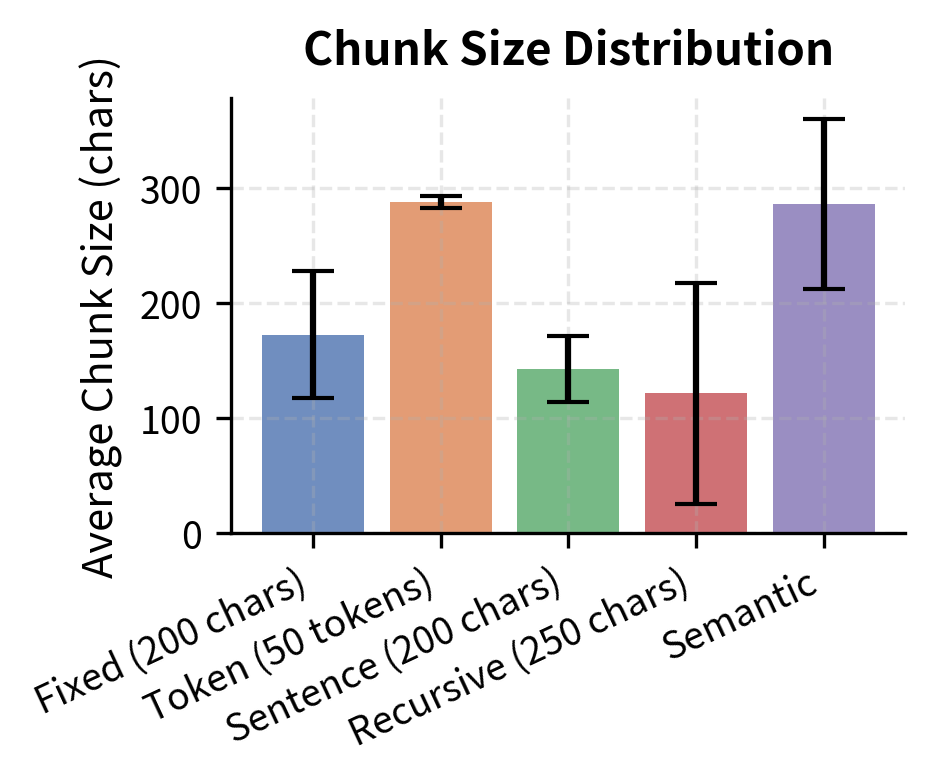

Let's compare all our strategies on the same document to see how they differ in practice. Applying each method to identical input text makes the differences concrete and allows us to observe how each strategy's assumptions about text structure manifest in the resulting chunks.

The results confirm our expectations. Fixed-size strategies produce uniform chunks but cut through text arbitrarily, while sentence-based and recursive strategies produce chunks of varying size that preserve linguistic coherence. The standard deviation of chunk sizes tells an important story: fixed-size methods have near-zero variance by construction, while linguistically aware methods trade that uniformity for meaningfulness. In practice, the slight unpredictability of chunk sizes is a small price to pay for chunks that an embedding model can actually make sense of.

Metadata Enrichment

Raw chunks lose their document context. A chunk about "Section 3.2: Results" is much more useful to an LLM if it knows this section comes from "Annual Report 2023" by "Acme Corp." Enriching chunks with metadata improves both retrieval accuracy and the quality of generated answers. Metadata transforms a chunk from an anonymous fragment of text into a situated piece of knowledge with provenance, position, and context.

Common metadata to attach to each chunk includes:

- Source document: filename, URL, or document ID

- Position: chunk index, page number, or section path

- Structural context: parent headers, preceding and following chunk IDs

- Document metadata: author, date, document type, language

This metadata becomes invaluable during the retrieval and generation stages. The chunk index lets you retrieve neighboring chunks for additional context: if a retrieved chunk does not contain quite enough information to answer a question, the system can automatically pull in the preceding or following chunks to expand the context window. The source attribution enables citation in the generated response, allowing the LLM to tell you exactly where its information came from. The character offsets make it possible to highlight the relevant passage in the original document, creating a seamless user experience that connects generated answers back to their source material. We will see how this metadata integrates with vector databases in the upcoming chapters on Vector Similarity Search and the HNSW Index.

Special Document Types

Different document formats require specialized chunking approaches. Here are considerations for the most common types.

- Code files: Chunk along function or class boundaries rather than by line count. A function split across two chunks will be incomprehensible in both. Parse the abstract syntax tree if possible to identify natural boundaries.

- Tables: Tables should generally be kept as single chunks, even if they exceed the normal chunk size. Splitting a table across chunks destroys its relational structure. Convert tables to a text representation (like Markdown or CSV format) that preserves row-column relationships.

- Conversational data: Chat logs and dialogue transcripts should be chunked by conversational turns or topic shifts, not by arbitrary size. Each chunk should contain enough turns to understand the context of the conversation.

- Legal and regulatory documents: These often have numbered sections and subsections with precise cross-references. Structural chunking that preserves section numbers and hierarchies is essential. A chunk referencing "as defined in Section 2.1(b)" is useless if you (or LLM) cannot trace that reference.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Despite the variety of strategies available, document chunking remains more art than science. No single strategy works optimally across all document types, query patterns, and embedding models. The fundamental challenge is that chunking decisions must be made at indexing time, before you know what questions you will ask. A chunk boundary that perfectly separates two topics for one query may split the exact passage needed for another.

Semantic chunking, while conceptually appealing, introduces its own challenges. It requires running an embedding model over every sentence during indexing, which significantly increases preprocessing time and cost. The quality of the splits depends heavily on the embedding model's ability to capture topic coherence, and models trained primarily on sentence similarity may not always detect document-level topic transitions accurately. Furthermore, semantic chunking can produce highly variable chunk sizes: a long section on a single topic might produce a single enormous chunk, while a passage that quickly surveys several topics might be split into tiny fragments. This variability can be managed with minimum and maximum size constraints, but adding these constraints partially undermines the semantic purity of the approach.

Another practical limitation is the interaction between chunk size and the downstream LLM's context window. If you retrieve five chunks of 500 tokens each, you consume 2,500 tokens of the LLM's context for retrieved content alone. With larger chunk sizes or more retrieved results, you may exhaust the context window before including your query and system instructions. This creates a system-level constraint that must be considered holistically: chunk size, number of retrieved results, prompt template length, and LLM context window all interact.

Finally, evaluation of chunking quality is inherently tied to end-to-end RAG performance. You cannot evaluate chunking in isolation because the same chunks might work well with one embedding model and poorly with another, or might retrieve perfectly but confuse a particular LLM. We will address this challenge systematically in the RAG Evaluation chapter later in this part.

Summary

Document chunking transforms large documents into retrieval-friendly pieces that each capture a focused topic. The key takeaways from this chapter are:

- Fixed-size chunking (by characters or tokens) is simple and fast but ignores text structure, often cutting through sentences and ideas.

- Sentence-based chunking uses linguistic boundaries to ensure each chunk contains complete sentences, producing more coherent embeddings at the cost of variable chunk sizes.

- Recursive chunking respects document hierarchy by trying paragraph boundaries first, then falling back to finer-grained splits, combining structural awareness with size control.

- Semantic chunking uses embeddings to detect topic shifts, placing boundaries where the text's meaning changes most dramatically.

- Chunk overlap ensures information near boundaries appears in multiple chunks, reducing the risk of losing cross-boundary context.

- Chunk size involves a precision-context trade-off: smaller chunks give more precise retrieval but less context, while larger chunks provide richer context but less focused embeddings. Typical values range from 200 to 1,000 tokens.

- Metadata enrichment preserves document context (source, position, section hierarchy) that would otherwise be lost during chunking, enabling better retrieval and citation.

In the next chapter, we will examine the embedding models that convert these chunks into the dense vectors used for retrieval, completing the connection between chunking decisions and retrieval quality.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about document chunking strategies and their impact on retrieval.

Comments