Learn chunking (shallow parsing) to identify noun phrases, verb phrases, and prepositional phrases using IOB tagging, regex patterns, and machine learning with NLTK and spaCy.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Chunking

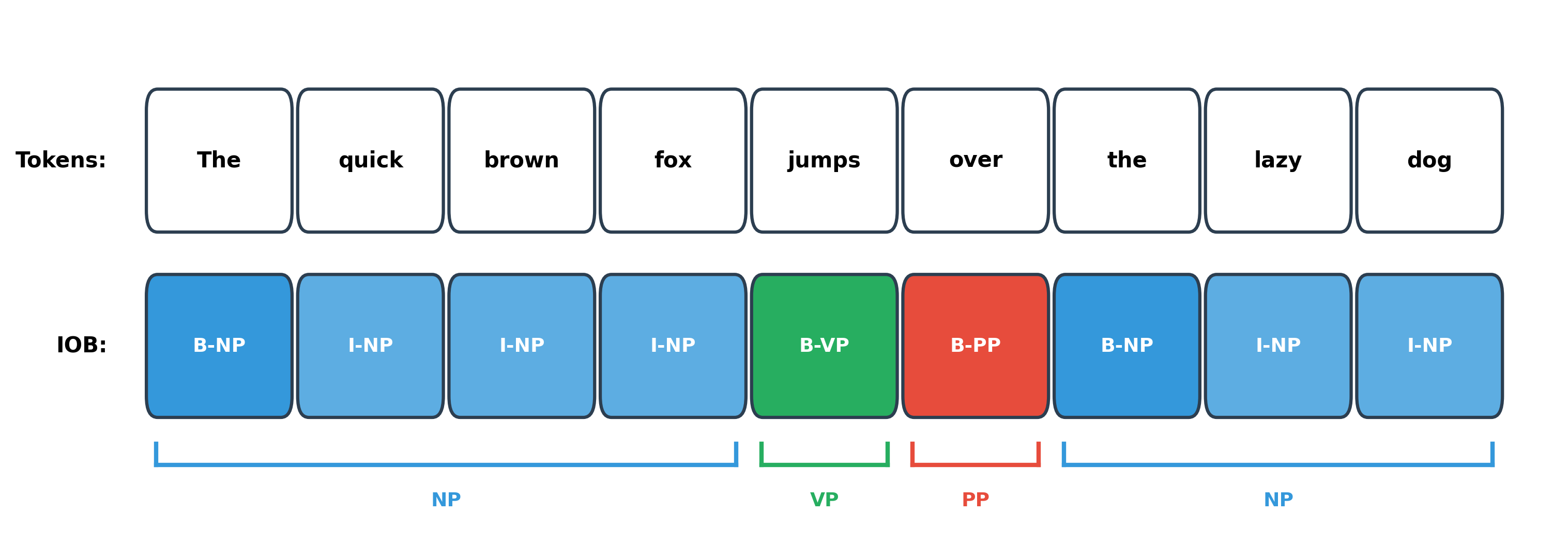

Sentences contain meaningful groups of words that function as units. In "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog," we naturally perceive "the quick brown fox" as a noun phrase describing the subject, "jumps" as the action, and "over the lazy dog" as a prepositional phrase describing where. Chunking, also called shallow parsing, identifies these non-overlapping segments without building a full syntactic tree.

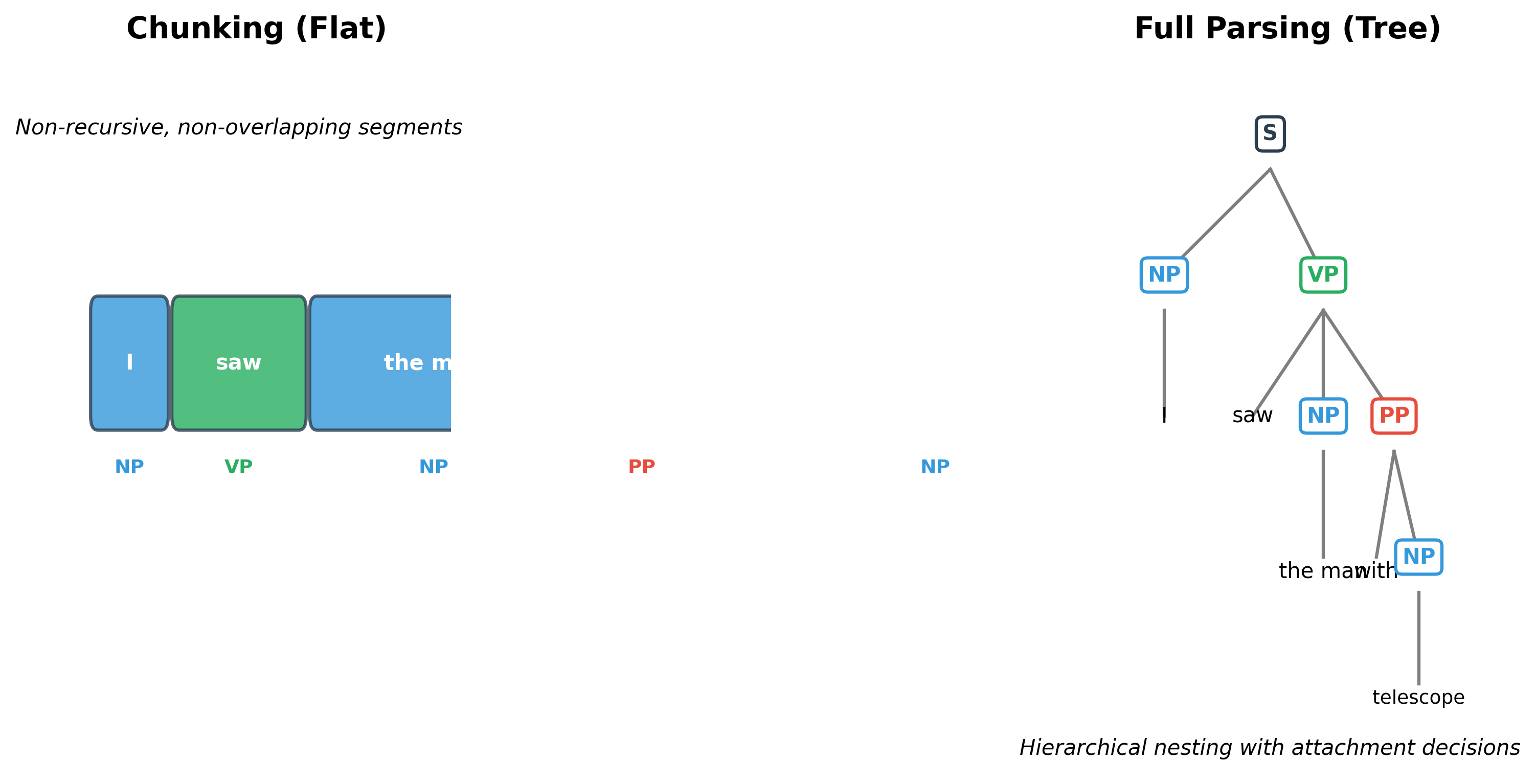

Chunking sits between part-of-speech tagging and full parsing in complexity. POS tagging labels individual words. Full parsing constructs hierarchical tree structures showing how phrases nest within phrases. Chunking finds a middle ground: it groups consecutive words into flat, non-recursive chunks without showing how chunks relate to each other.

This chapter explores chunking from multiple angles. You'll learn the major chunk types, understand how IOB tagging represents chunk boundaries, implement chunkers using both regular expressions and machine learning, and see how chunking serves as a preprocessing step for information extraction and other downstream tasks.

What Is Chunking?

Chunking identifies contiguous spans of tokens that form syntactic units. Unlike full parsing, which produces tree structures with unlimited nesting, chunking produces a flat sequence of labeled segments. Each token belongs to exactly one chunk (or no chunk if it's outside all chunks).

Chunking is the task of grouping consecutive words into non-overlapping, non-recursive phrases such as noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP), and prepositional phrases (PP). It identifies phrase boundaries without building hierarchical parse trees.

Consider the sentence "The black cat sat on the mat." A chunker might produce:

- [The black cat], noun phrase (subject)

- [sat], verb phrase (predicate)

- [on], prepositional phrase start

- [the mat], noun phrase (object of preposition)

The key properties of chunking are:

- Non-overlapping: Each word belongs to at most one chunk

- Non-recursive: Chunks don't contain other chunks of the same type

- Contiguous: Chunks consist of consecutive words

- Partial coverage: Some words may not belong to any chunk

Let's see chunking in action with NLTK:

NLTK's ne_chunk function produces a tree structure, but we can flatten it to see the chunks:

Chunk Types

Different chunk types capture different syntactic units. The most common types in English are noun phrases, verb phrases, and prepositional phrases, though chunking schemes may include additional categories.

Noun Phrases (NP)

Noun phrases are the most important and well-studied chunk type. They typically consist of a determiner, optional adjectives, and one or more nouns. NP chunking, specifically, is sometimes called "base NP chunking" when it identifies only the innermost, non-recursive noun phrases.

The structure of noun phrases follows grammatical patterns. A determiner (the, a, my) often starts the phrase, adjectives modify the head noun, and the head noun itself can be singular, plural, or proper. Understanding these patterns is key to building effective chunkers.

Verb Phrases (VP)

Verb phrases contain the main verb and its auxiliaries. In chunking, we typically identify just the verbal elements, not the objects or complements that would be included in a full verb phrase in traditional grammar.

Prepositional Phrases (PP)

Prepositional phrases begin with a preposition and typically end with a noun phrase. In chunking, we often identify the preposition separately and let the following NP be tagged as such, or we group them together.

Other Chunk Types

Depending on the annotation scheme, chunkers may identify additional phrase types:

IOB Tagging for Chunks

Just as BIO tagging encodes entity boundaries for named entity recognition, IOB tagging encodes chunk boundaries. Each token receives a tag indicating whether it begins a chunk (B), continues a chunk (I), or is outside all chunks (O).

IOB (Inside-Outside-Beginning) tagging represents chunk boundaries using per-token labels. B-NP marks the first word of a noun phrase, I-NP marks subsequent words in the same NP, and O marks words outside any chunk. This encoding is identical to BIO tagging for NER.

The terminology varies slightly. Some sources use "BIO" while others use "IOB." Additionally, there are two variants:

- IOB1: B tag is only used when a chunk follows another chunk of the same type

- IOB2: B tag is always used for the first token of a chunk (more common)

Let's see IOB tagging applied to chunks:

Converting Between Chunks and IOB Tags

We need utilities to convert between chunk spans and IOB sequences, just as we did for named entity recognition in the BIO tagging chapter:

Chunking vs. Full Parsing

Understanding the difference between chunking and full parsing clarifies when to use each approach.

Full syntactic parsing produces a complete tree structure showing how phrases nest within phrases. Consider "I saw the man with the telescope." A full parse would show the PP "with the telescope" attaching either to "saw" (I used the telescope to see) or to "the man" (the man had the telescope). This ambiguity requires semantic knowledge to resolve.

The key tradeoffs are:

- Speed: Chunking is much faster than full parsing

- Accuracy: Chunking achieves higher accuracy on its simpler task

- Information: Full parsing captures more syntactic detail

- Ambiguity: Chunking avoids attachment decisions that require semantics

For many practical applications like information extraction, named entity recognition, and text classification, chunking provides sufficient structure without the complexity and errors of full parsing.

Regex-Based Chunking with NLTK

NLTK provides a RegexpParser that lets you define chunk patterns using regular expressions over POS tags. This approach is intuitive and works well for simple patterns.

Let's break down the grammar pattern for noun phrases:

Chinking: Defining What's NOT in a Chunk

Sometimes it's easier to define what shouldn't be in a chunk than what should. Chinking removes tokens from chunks:

The }{ syntax means "end chunk before these tags, start new chunk after." This effectively splits chunks at verbs, prepositions, and other non-NP elements.

Limitations of Regex Chunking

Regex-based chunking is simple and fast but has limitations:

Regex patterns match local sequences without considering broader context. They rely entirely on POS tags, so POS tagging errors propagate. They cannot handle discontinuous constituents or truly recursive structures.

Using the CoNLL-2000 Dataset

The CoNLL-2000 shared task established a standard benchmark for chunking. The dataset provides sentences with POS tags and IOB chunk labels for training and evaluating chunkers.

Converting CoNLL Data to IOB Format

For machine learning approaches, we need the data in token-level IOB format:

Evaluating Chunkers

Chunking evaluation uses precision, recall, and F1 score at the chunk level, not the token level. A chunk is correct only if both its boundaries and type match exactly.

Chunking evaluation counts a predicted chunk as correct only if it exactly matches a gold chunk in both boundaries (start and end positions) and type (NP, VP, etc.). Partial matches receive no credit.

Chunking as Preprocessing

Chunking serves as a preprocessing step for many NLP tasks. By identifying phrase boundaries, it simplifies downstream processing and provides useful features.

Information Extraction

Chunking helps identify entities and relations in text:

Keyword Extraction

Noun phrases often contain important keywords:

Question Answering Preprocessing

Chunking can identify answer candidates in question answering:

Training a Chunker with Machine Learning

While regex chunkers are simple, machine learning approaches achieve better accuracy by learning patterns from data. Let's train a simple chunker using features.

The unigram chunker learns which IOB tag typically follows each POS tag. It captures patterns like "DT usually starts an NP (B-NP)" and "JJ inside an NP usually continues it (I-NP)."

Using More Context

A bigram tagger uses the previous POS tag as additional context:

Chunking with spaCy

spaCy provides noun phrase chunking through its noun_chunks property, which uses dependency parsing under the hood:

spaCy's noun chunks are derived from the dependency parse, so they benefit from syntactic analysis beyond just POS tag patterns. The root of each chunk is its head noun, and the dep_ attribute shows its grammatical function in the sentence.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Chunking, while useful, has inherent limitations that practitioners should understand.

The flat, non-recursive nature of chunks means they cannot represent certain linguistic phenomena. A sentence like "The student who failed the exam requested a meeting" contains a relative clause embedded within the subject NP. Flat chunking either splits this incorrectly or produces an overly long NP that obscures internal structure. When you need to understand how phrases nest within phrases, full parsing is required.

Chunking accuracy depends heavily on POS tagging accuracy. If "man" is tagged as a noun when it's actually a verb in "The old man the boats," chunking will produce incorrect results. This error propagation is particularly problematic for domain-specific text where POS taggers trained on news data may struggle with unfamiliar vocabulary and constructions.

The definition of chunks can be ambiguous. Should "the very best coffee" be one NP or should "very best" be a separate ADJP? Different annotation guidelines make different choices, and these inconsistencies affect both training data and evaluation. When comparing chunking systems, ensure they use compatible annotation schemes.

For languages with freer word order than English, chunking becomes more challenging. German verb clusters, Japanese postpositions, and Arabic clitic attachment create patterns that simple sequence models may not capture well. Cross-linguistic chunking remains an active research area.

Despite these limitations, chunking provides a practical balance between simplicity and usefulness. For applications that need phrase boundaries without full syntactic analysis, such as information extraction, keyword identification, and text summarization, chunking offers an efficient and reasonably accurate solution.

Summary

Chunking identifies non-overlapping, non-recursive phrases in text, providing a middle ground between POS tagging and full parsing. The key concepts from this chapter:

- Chunk types include noun phrases (NP), verb phrases (VP), and prepositional phrases (PP). Each type captures a different syntactic unit, with NP chunking being the most studied and practically useful.

- IOB tagging encodes chunk boundaries using per-token labels: B marks the beginning of a chunk, I marks continuation, and O marks tokens outside chunks. This encoding allows chunking to be formulated as a sequence labeling task.

- Regex-based chunking uses patterns over POS tags to identify chunks. NLTK's

RegexpParserprovides an intuitive way to define chunk grammars, though pattern-based approaches have limited accuracy. - Machine learning chunkers learn patterns from annotated data like the CoNLL-2000 corpus. Even simple unigram and bigram models outperform hand-crafted rules, and more sophisticated approaches using CRFs or neural networks achieve state-of-the-art results.

- Chunking vs. parsing represents a key tradeoff: chunking is faster and more accurate on its simpler task but captures less syntactic information. Full parsing resolves attachment ambiguities and represents hierarchical structure.

- Practical applications include information extraction, keyword identification, and question answering preprocessing. Chunking provides useful features without the complexity of full parsing.

Key Parameters

When working with chunking in NLTK and spaCy:

NLTK RegexpParser:

grammar: A string defining chunk rules using regex over POS tags{<pattern>}: Chunk pattern (include matching tokens)}<pattern>{: Chink pattern (exclude matching tokens)

NLTK chunk evaluation:

chunk_types: List of chunk types to evaluate (e.g.,["NP", "VP", "PP"])- Evaluation is chunk-level: exact boundary and type match required

spaCy noun_chunks:

doc.noun_chunks: Iterator over noun phrases in documentchunk.root: Head noun of the chunkchunk.root.dep_: Syntactic dependency of the head

The next chapters explore the probabilistic models, Hidden Markov Models and Conditional Random Fields, that power production-quality chunkers and other sequence labeling systems.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about chunking and shallow parsing.

Comments