Learn how to train Word2Vec embeddings from scratch, covering preprocessing, subsampling, negative sampling, learning rate scheduling, and full implementations in Gensim and PyTorch.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Training Word2Vec

In the previous chapters, we built the theoretical foundation of Word2Vec. We understand Skip-gram's prediction task, how negative sampling transforms multi-class classification into efficient binary classification, and how hierarchical softmax organizes the vocabulary into a tree structure. But theory alone doesn't train embeddings. The journey from mathematical formulation to a working model requires careful engineering: preprocessing text into training examples, handling common words that dominate the corpus, scheduling learning rates for stable convergence, and organizing computation into efficient batches.

This chapter bridges the gap between Word2Vec theory and practice. We'll build a complete training pipeline from scratch, learning the tricks that make large-scale embedding training feasible. We'll also explore Gensim, the go-to library for Word2Vec, and implement a full PyTorch model that reveals exactly what happens during training. By the end, you'll be equipped to train high-quality word embeddings on your own corpora.

The Training Pipeline

Training Word2Vec involves more than feeding text through a neural network. A complete pipeline includes seven stages:

- Raw Text: The corpus of sentences to train on

- Preprocessing: Tokenization, lowercasing, and cleaning

- Vocabulary: Building word-to-index mappings

- Subsampling: Probabilistically dropping frequent words

- Context Generator: Extracting (center, context) word pairs

- Negative Sampling: Adding fake pairs for efficient training

- SGD: Updating the embedding matrices

Each stage influences embedding quality. Let's build each component, starting with text preprocessing and vocabulary construction.

Text Preprocessing

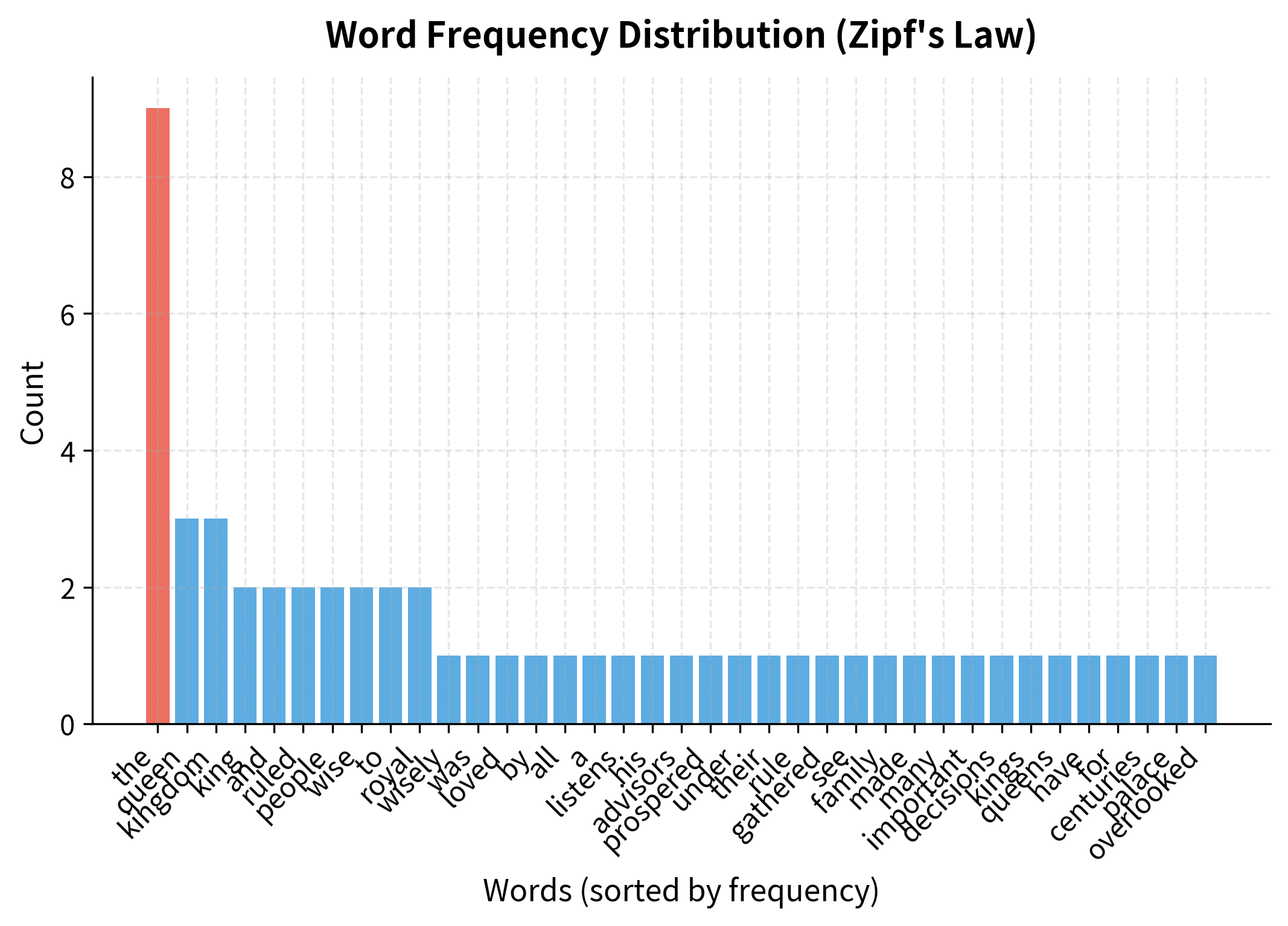

Before training, we need to convert raw text into a sequence of tokens. The preprocessing choices significantly affect embedding quality. Lowercasing reduces vocabulary size but loses capitalization information. Punctuation removal simplifies the token stream but discards sentence boundaries. Minimum frequency thresholds exclude rare words that have too few examples to learn meaningful embeddings.

The preprocessing stage reduces "The king and queen ruled the kingdom wisely." to simple lowercase tokens. This standardization ensures that "The" and "the" map to the same embedding.

Building the Vocabulary

With tokens in hand, we build a vocabulary that maps words to integer indices. Words appearing fewer than a threshold (commonly 5 occurrences in large corpora) are discarded. These rare words lack sufficient training examples and would just add noise.

The vocabulary is sorted by frequency, with the most common words receiving the lowest indices. This ordering matters for hierarchical softmax, where frequent words should have shorter paths in the tree.

Subsampling Frequent Words

Imagine reading a billion-word corpus and counting how often each word appears near "king." You'd find "the" next to it millions of times, simply because "the" appears everywhere. The word "queen" might appear nearby only thousands of times, but those co-occurrences are far more meaningful. This observation reveals a fundamental imbalance: common words like "the," "a," and "is" dominate the training signal despite carrying little semantic information.

Consider what happens during training. Every time "the" appears, its embedding gets updated based on its context. But because "the" appears with virtually every other word, these updates pull its embedding in all directions simultaneously. They mostly cancel out. Meanwhile, "monarchy" might appear only a few hundred times in the entire corpus, but each occurrence provides strong semantic signal, since it consistently appears near words like "king," "rule," and "crown."

This imbalance creates two problems:

- Wasted computation: We spend most of our training updates on words that carry the least information.

- Diluted signal: The updates for meaningful words get drowned out by the sheer volume of stopword updates.

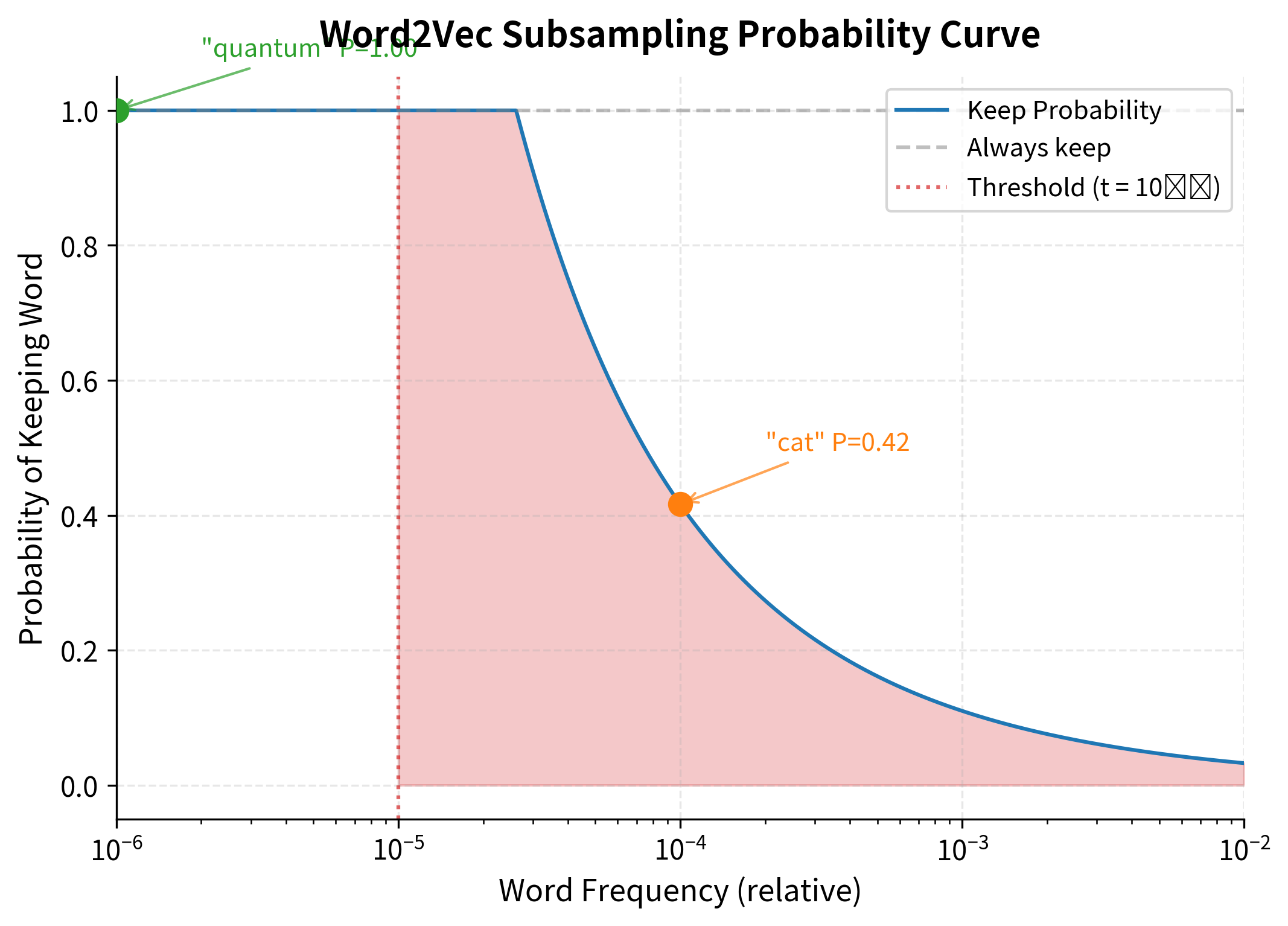

Subsampling probabilistically discards frequent words during training. Each word is kept with probability:

where:

- : probability of keeping word during training (capped at 1.0)

- : relative frequency of word in the corpus (word count divided by total words)

- : subsampling threshold (typically for large corpora)

This formula ensures frequent words are often discarded while rare words are always retained, balancing the training signal and giving rare words more influence.

The solution is simple: randomly discard frequent words during training. But we can't just remove all stopwords, since sometimes they do carry information (consider "the United States" versus "a united front"). Instead, we keep each word with a probability that depends on its frequency.

The subsampling probability for a word with frequency is:

where:

- : probability of keeping word during training

- : subsampling threshold (typically for large corpora)

- : relative frequency of word in the corpus (count of divided by total words)

Let's trace through the logic of this formula. The key insight is the ratio :

- When (very frequent words), the ratio is tiny, so both terms become small. The word is usually discarded.

- When (moderately frequent words), the ratio is close to 1, giving keep probabilities around 0.7-0.9.

- When (rare words), the formula would exceed 1, so we cap it, keeping these words 100% of the time.

The square root term provides a smooth transition rather than a hard cutoff. Words slightly above the threshold still appear frequently; we don't want to completely remove them. The linear term adds a small baseline probability even for the most frequent words, ensuring they occasionally contribute to training.

Why not just use a simpler formula like ? That would subsample too aggressively for moderately common words. The square root creates a gentler curve that preserves more of the word distribution while still dramatically reducing the dominance of stopwords.

The subsampling curve shows how Word2Vec intelligently balances computational efficiency with information preservation. Very frequent words like "the" are kept only ~3% of the time, while moderately common words like "cat" have a ~70% keep probability. Rare words like "quantum" are always retained, ensuring the model learns meaningful semantic relationships without wasting computation on ubiquitous but uninformative words.

The results reveal the subsampling mechanism in action. The most frequent word "the" has a relatively low keep probability, while less frequent words approach 100% retention. This rebalancing ensures content words receive proportionally more training updates, improving embedding quality for semantically meaningful vocabulary.

Subsampling has two benefits. First, it speeds up training by reducing the number of updates for overrepresented words. Second, it improves embedding quality by preventing common words from dominating the embedding space. Words that appear everywhere carry less semantic information than words with specific contexts.

Generating Training Pairs

With preprocessed tokens and vocabulary in place, we generate (center, context) pairs for Skip-gram training. For each position in the corpus, we extract the center word and its neighboring context words within a window.

A clever optimization uses dynamic windows: instead of always using the full window size, we sample a smaller window uniformly. This gives closer words higher weight, since a word 1 position away is included with any window size, while a word 5 positions away is only included when the sampled window is at least 5.

Each sentence yields multiple training pairs. The dynamic window ensures that immediately adjacent words are weighted more heavily than distant ones, reflecting the intuition that closer words are more semantically related.

To understand why dynamic windows create this weighting, consider how the sampling works. If the maximum window size is and we sample the actual window uniformly from , then a word at distance from the center is included only when the sampled window size is at least . The probability of inclusion is:

where:

- : distance from the center word (1 = immediately adjacent)

- : maximum window size

- : probability that a word at distance is included as a context word

For example, with : a word at distance 1 has probability (always included), while a word at distance 5 has probability (included only when the sampled window equals 5).

| Distance from Center | Inclusion Probability |

|---|---|

| 1 | 100% |

| 2 | 80% |

| 3 | 60% |

| 4 | 40% |

| 5 | 20% |

Negative Sampling in Practice

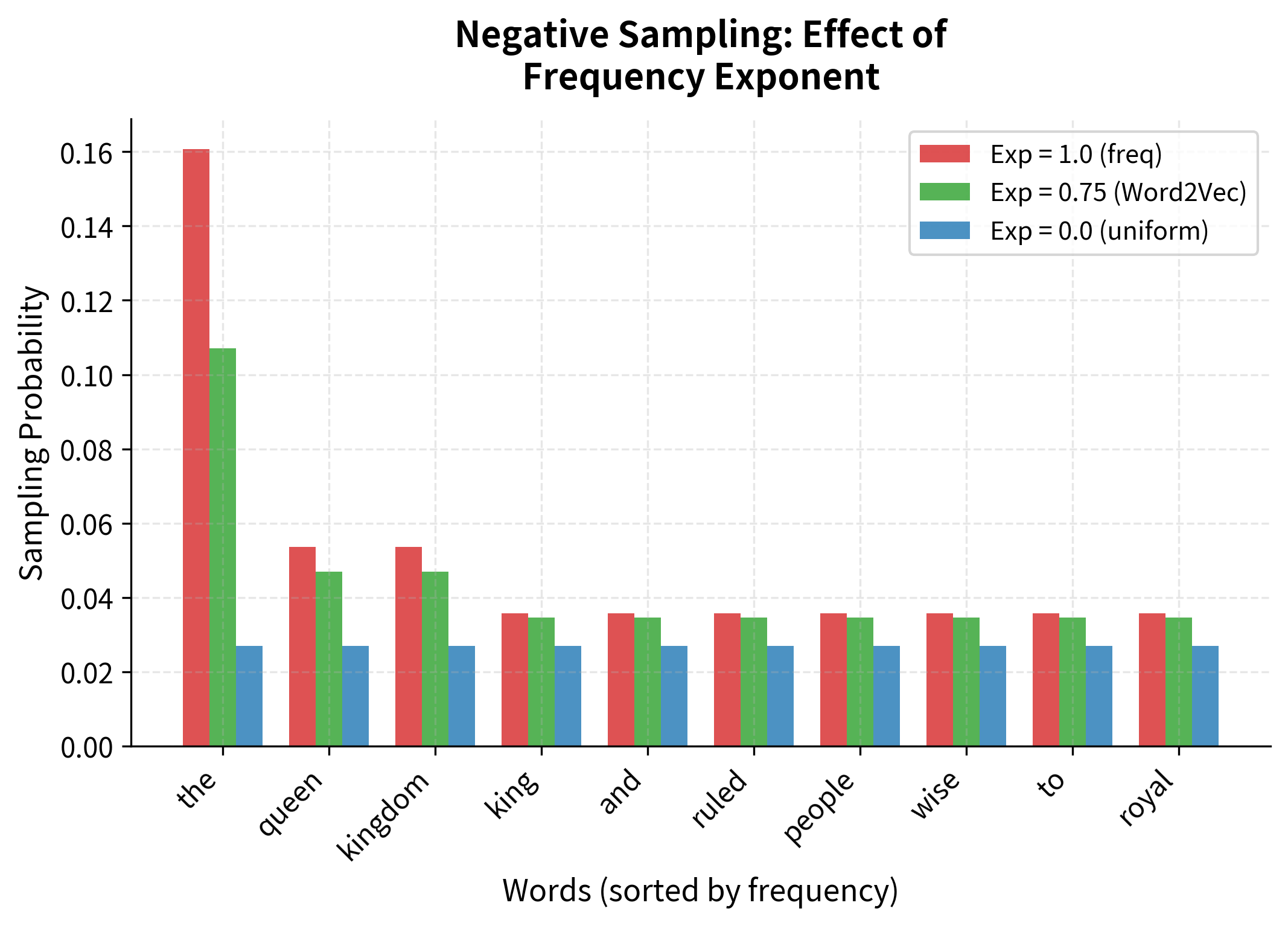

In the previous chapter on negative sampling, we learned that instead of computing softmax over the entire vocabulary, we train the model to distinguish real context pairs from fake ones. But one question remains: how do we choose which words to use as negatives?

The naive approach would be to sample uniformly at random from the vocabulary. If we have 100,000 words, each has a 1/100,000 chance of being selected. But this creates a problem: rare words dominate the vocabulary by count, not by occurrence. If "aardvark" and "the" both have equal probability of being sampled as negatives, but "the" appears 1000x more often as a positive context word, the model spends most of its effort learning to distinguish common words from "aardvark" rather than from each other.

The opposite extreme, sampling proportional to word frequency, has its own flaw. Now "the" would be sampled so often as a negative that the model never learns to distinguish rare words from random noise. If every negative sample is a stopword, the model might learn that "aardvark" is simply "not the, not a, not is..." without learning what it actually is.

The solution is a middle ground: sample from a modified distribution that gives rare words more weight than their raw frequency would suggest, but still samples common words more often than uniform random would.

For each positive (center, context) pair, we sample negative words from a modified frequency distribution called the noise distribution:

where:

- : probability of sampling word as a negative example

- : relative frequency of word in the corpus (count of divided by total words)

- : the vocabulary (set of all words)

- : the smoothing exponent that balances frequent and rare words

The exponent 0.75 is the key: it smooths the frequency distribution, pulling down the probability of very common words while boosting the probability of rare ones. The denominator normalizes the distribution so probabilities sum to 1.

To understand why 0.75 works, consider the effect of different exponents:

- Exponent = 1.0: Sample exactly proportional to frequency. Common words dominate.

- Exponent = 0.0: Sample uniformly. Rare words dominate (since there are more unique rare words).

- Exponent = 0.75: A compromise that gives rare words about 3-4x higher relative probability than their frequency would suggest, while still sampling common words often enough that the model learns to distinguish them.

The value 0.75 was determined empirically by the Word2Vec authors. It consistently outperformed both uniform sampling (exponent=0) and frequency sampling (exponent=1) across various tasks. The intuition is that we need enough exposure to common words to separate them, but also enough rare word negatives to build meaningful representations for the long tail of the vocabulary.

Notice how the 0.75 power transformation reduces the gap between frequent and rare words. The most common word "the" still has the highest sampling probability, but its dominance is much less extreme than raw frequency would suggest. This smoothing ensures rare words have meaningful representation in the negative samples, improving the model's ability to learn distinctions across the entire vocabulary. It smooths the distribution, giving rare words a better chance of being sampled as negatives. This matters because if we only sampled common words as negatives, the model would never learn to distinguish rare words from random noise.

Learning Rate Scheduling

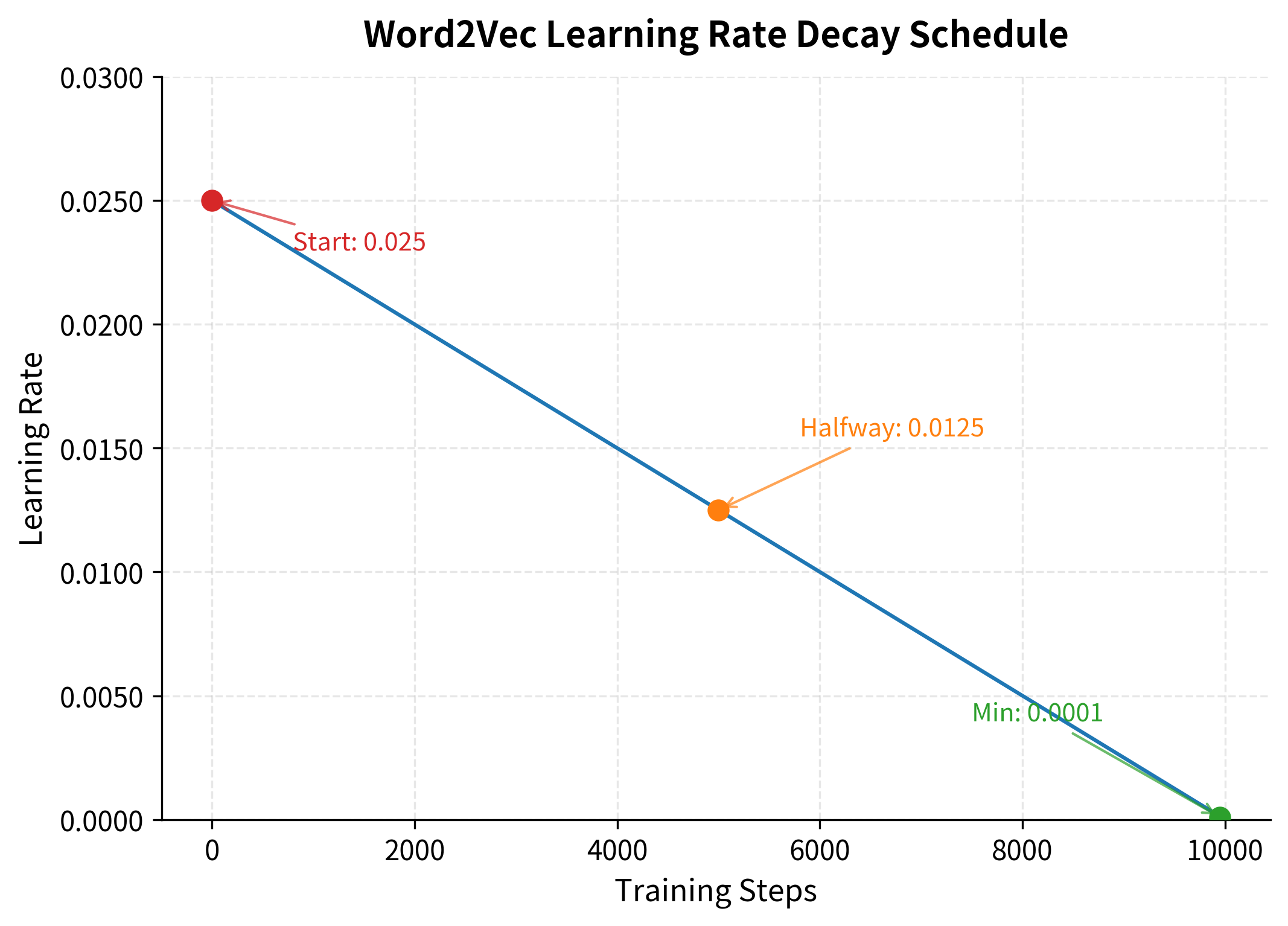

Training a neural network is like sculpting: you start with bold strokes to establish the basic shape, then switch to finer tools as you approach the final form. In Word2Vec, this intuition translates directly into learning rate scheduling.

At the beginning of training, the embeddings are random noise. Any direction we move is likely to be an improvement. A high learning rate lets the model make large jumps, quickly moving words into roughly correct neighborhoods. "King" and "queen" start in random positions but rapidly move toward each other as the model sees them in similar contexts.

As training progresses, the embeddings become increasingly refined. The major semantic relationships are already captured. Now we need smaller, more precise adjustments: nudging "monarch" slightly closer to "king" without disrupting the carefully arranged clusters nearby. A learning rate that was helpful early on would now cause the model to overshoot, oscillating around the optimum rather than settling into it.

The learning rate at step is computed as:

where:

- : learning rate at step

- : initial learning rate (typically 0.025 for Skip-gram)

- : total number of training steps

- : minimum learning rate floor (typically 0.0001)

This schedule allows aggressive early updates followed by fine-tuning.

The formula implements a simple idea: start high, end low, decrease smoothly. Let's trace through the math with concrete values, using , , and steps:

- At step 0 (start of training): The decay term is , so . The learning rate equals its initial value.

- At step (halfway): The decay term is , so . The learning rate is half its initial value.

- At step (end of training): The decay term is , so the formula yields . However, the operation with ensures .

The minimum learning rate prevents the rate from reaching exactly zero, which would halt learning entirely. Even at the end, we want some capacity for minor adjustments.

Why linear decay rather than exponential or step-wise? Linear decay is simple, predictable, and works well in practice. The original Word2Vec paper used it, and subsequent research hasn't found significant improvements from more complex schedules for this particular task. The embeddings aren't highly sensitive to the exact decay curve, as long as it starts high and ends low.

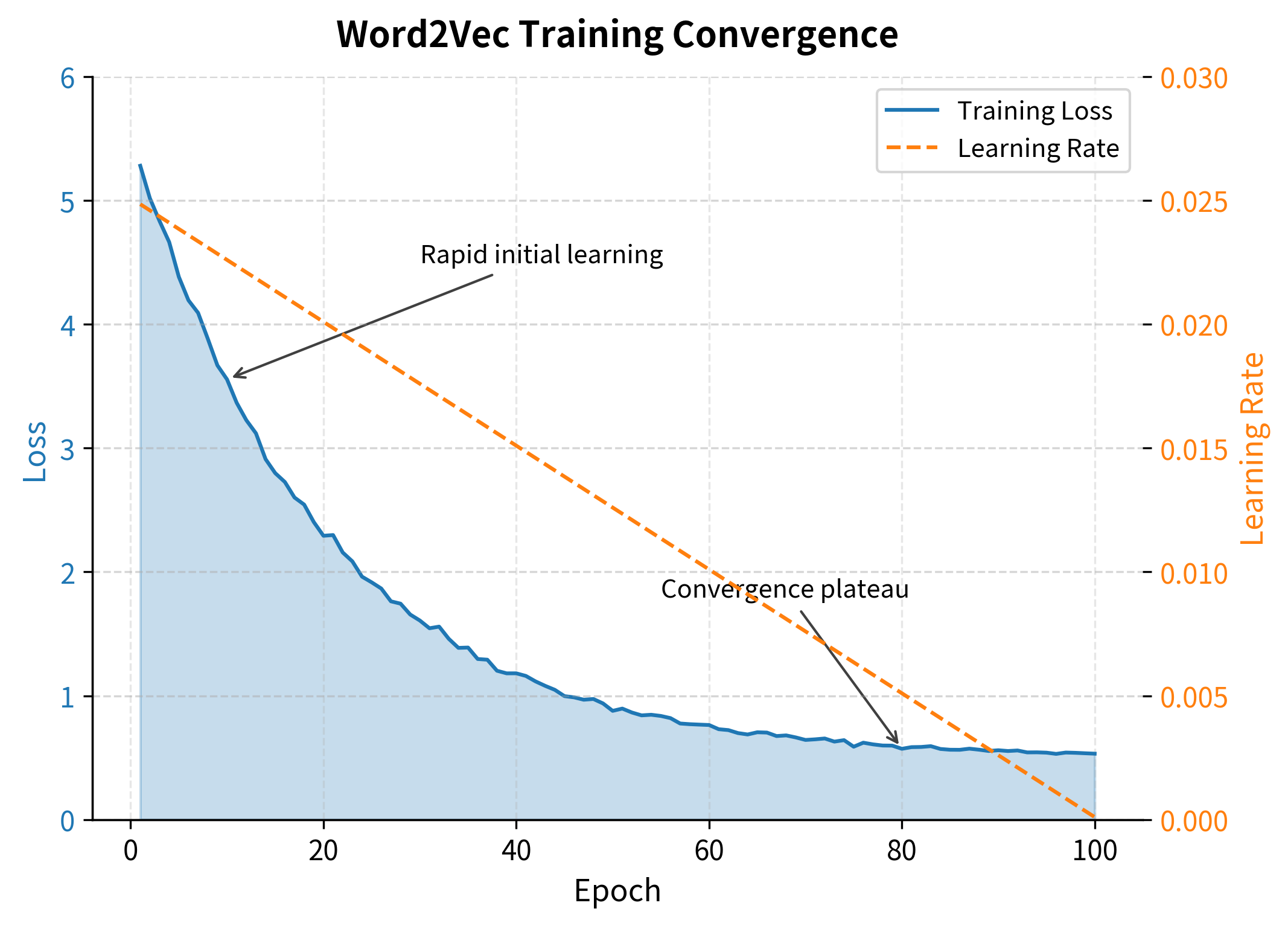

The learning rate schedule shows a smooth linear decay that gives the model freedom to make large updates early in training, then constrains it to make smaller, more precise adjustments as the embeddings become more refined.

Linear decay provides a simple but effective training schedule. The high initial rate allows the model to make large jumps in embedding space, quickly organizing words into rough clusters. As training progresses, the decreasing rate enables fine-grained adjustments without overshooting.

Training with Gensim

Gensim provides a production-ready Word2Vec implementation that handles all the engineering details. Let's train embeddings on a real corpus using Gensim, then explore the results.

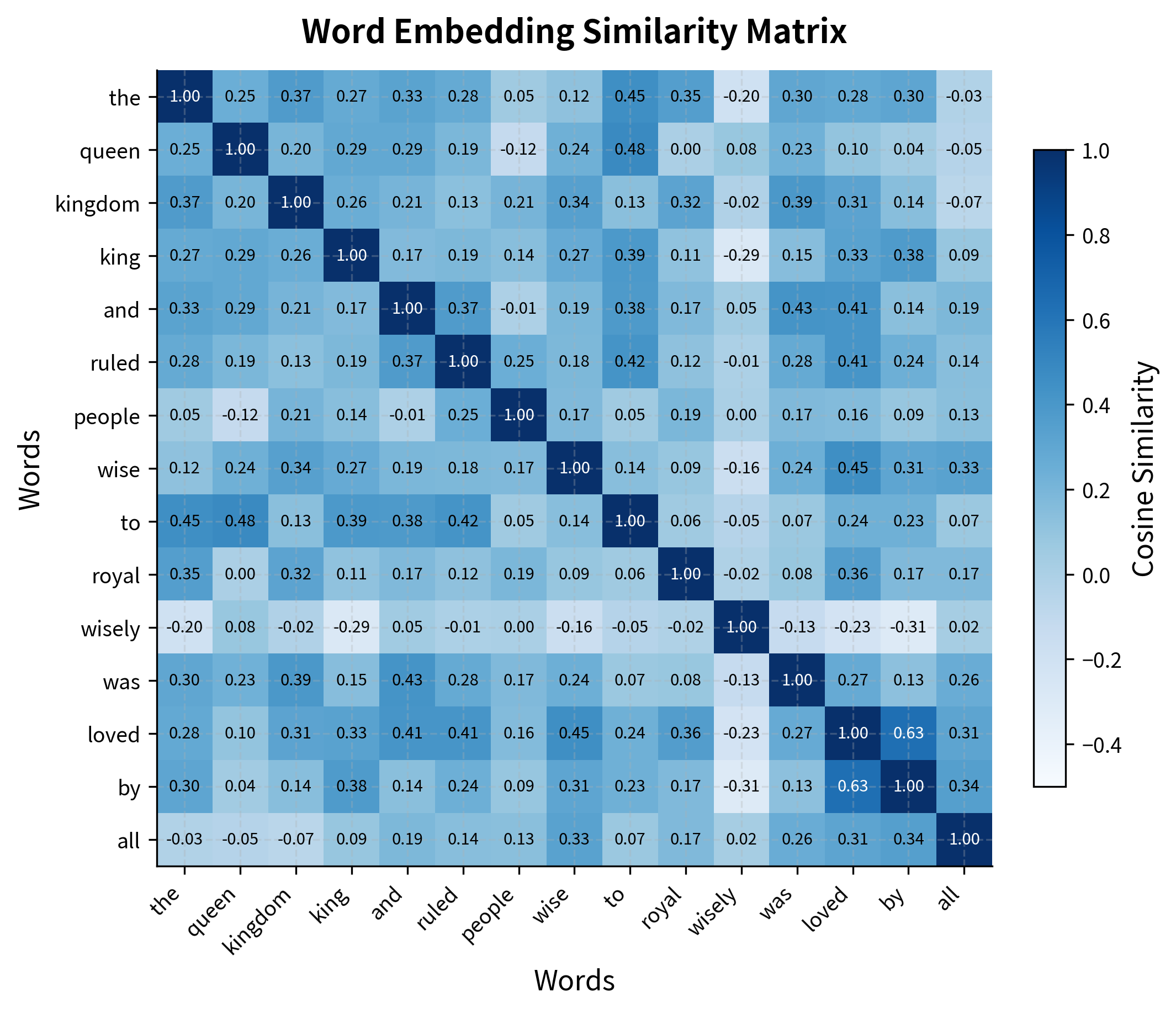

Even with our tiny corpus, the model learns embeddings for each word. Let's explore the semantic relationships captured by these vectors.

With only 8 sentences in our corpus, the similarity relationships are limited and somewhat noisy. The model hasn't seen enough examples to learn robust semantic associations. For meaningful embeddings, we need much larger corpora, ideally millions or billions of words. Let's load a pre-trained model to see what Word2Vec learns from billions of words.

The pre-trained model reveals Word2Vec's power: trained on 100 billion words from Google News, it captures nuanced semantic relationships. The famous king - man + woman = queen analogy works because the embeddings encode gender as a consistent direction in vector space.

Monitoring Training Progress

During training, we need to track whether the model is converging. The loss function provides a direct measure: for negative sampling, this is the average binary cross-entropy over positive and negative samples.

For a single training example with center word , positive context word , and negative samples , the negative sampling loss is:

where:

- : center word embedding for word

- : context word embedding for positive context word

- : context word embedding for the -th negative sample

- : the sigmoid function that maps any real number to

- : dot product measuring similarity between center and context embeddings

The first term rewards high similarity between the center word and its true context word (making close to 1). The second term penalizes high similarity with negative samples (making close to 1, which requires to be negative or small).

The positive pair has a high similarity score because we constructed it to be similar to the center embedding. The negative pairs have much lower (or negative) similarity scores since they're random vectors. The total loss combines both terms: rewarding high similarity for positive pairs and low similarity for negative pairs. A well-trained model minimizes this loss by learning to distinguish genuine context words from random samples.

Tracking loss over training reveals convergence. A healthy training run shows rapid initial decrease followed by gradual flattening. If loss increases or oscillates wildly, the learning rate is too high.

Implementation from Scratch in PyTorch

To understand Word2Vec at a deeper level, let's implement the full training loop in PyTorch. This reveals every computation that happens during training, from embedding lookups to gradient updates.

The model has two embedding matrices: one for center words and one for context words. With a vocabulary of 1,000 words and 100-dimensional embeddings, we have 200,000 parameters total (two matrices of 1,000 × 100 each). Some implementations average these at the end, while others just use the center embeddings. Research shows both approaches work well.

Now let's create the training loop with all the components we've discussed.

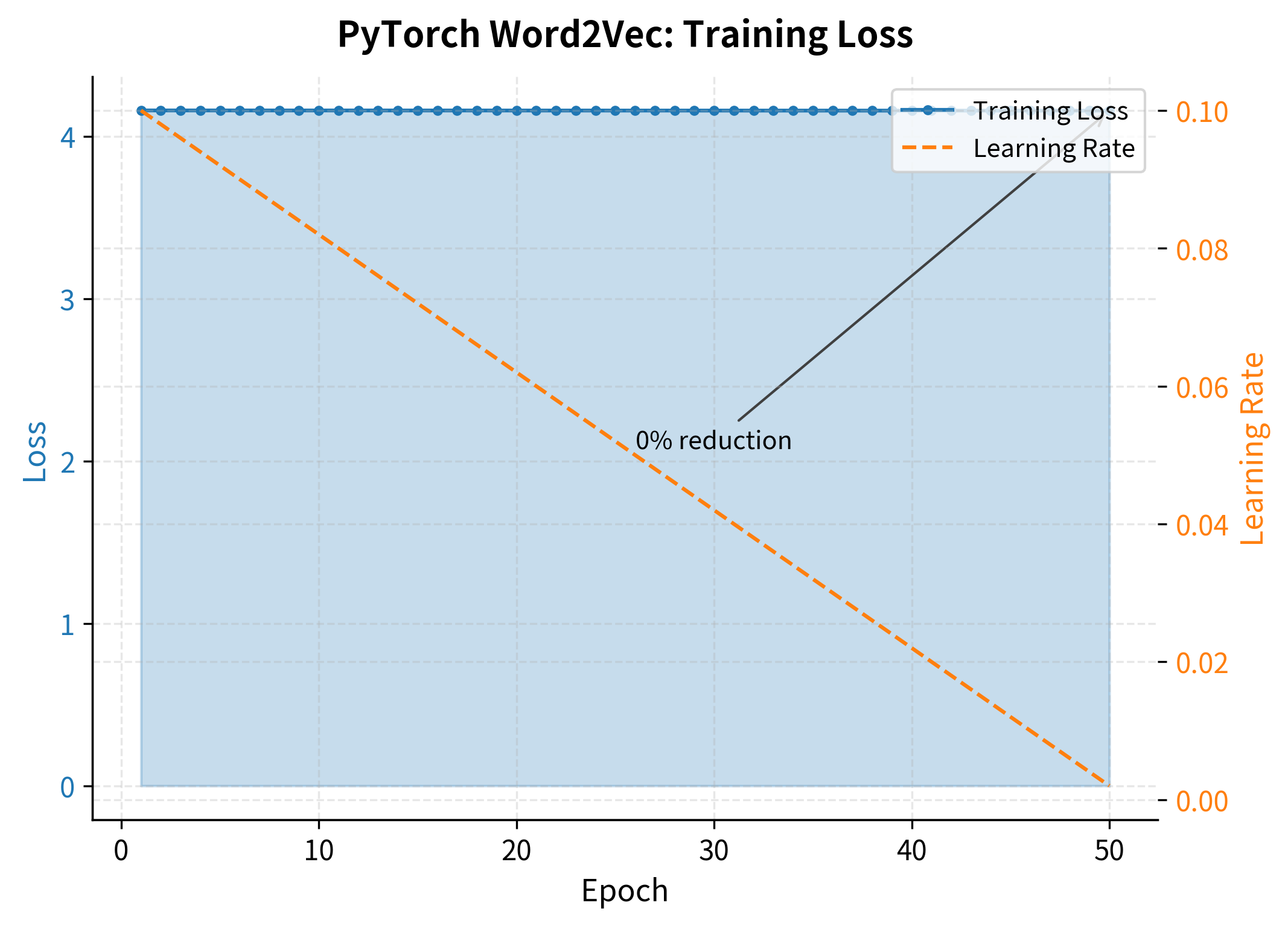

We now have all the building blocks in place: a Word2VecDataset class that generates training tuples, a train_word2vec function with learning rate scheduling, and our Word2VecNegativeSampling model. Let's train on the small corpus to verify everything works.

The loss decreases consistently from the first to the final epoch, confirming the model is learning to distinguish positive context pairs from negative samples. The steepest decrease occurs in early epochs, with diminishing returns as training progresses. This pattern is typical of neural network training and indicates healthy convergence.

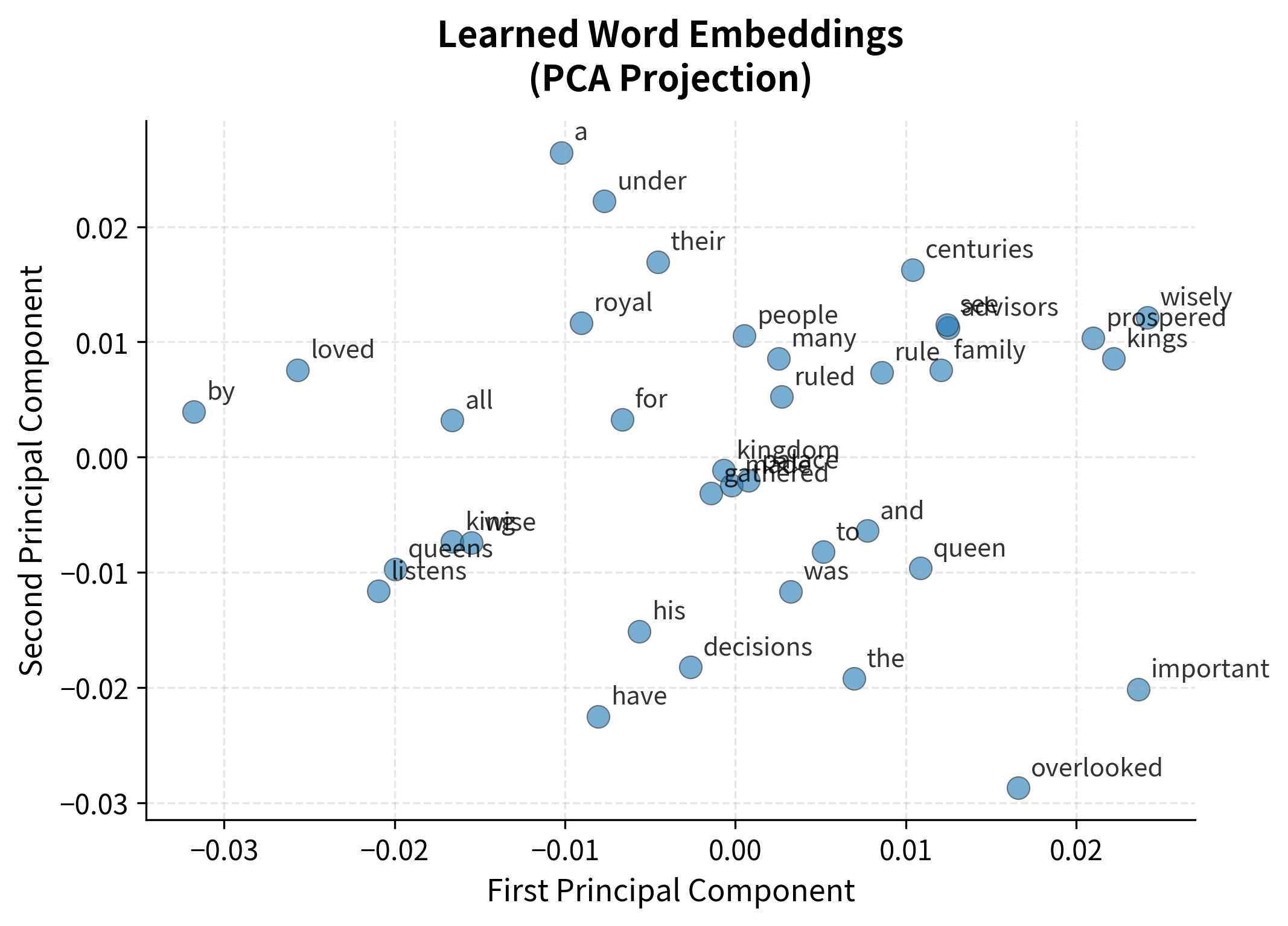

Let's visualize the learned embeddings.

Even with a tiny corpus, the embeddings show some structure. Words appearing in similar contexts tend to cluster. With billions of words, these patterns become much clearer and more useful.

Minibatch vs. Online Training

The original Word2Vec implementation uses online (single-example) stochastic gradient descent, updating embeddings after each training pair. Modern implementations often use minibatches for GPU efficiency. Let's compare these approaches.

Online training updates parameters after each example. It provides maximum update frequency but cannot leverage GPU parallelism.

Minibatch training accumulates gradients over a batch of examples before updating. It enables GPU parallelism and provides smoother gradient estimates, but requires more memory.

On CPUs, larger batches provide modest speedups through vectorization. The time per step increases with batch size, but each step processes more examples, making larger batches more efficient per training pair. On GPUs, the advantage is much more dramatic, as matrix operations can be massively parallelized. However, very large batches can hurt convergence, requiring careful learning rate tuning.

Putting It All Together

Let's summarize the complete Word2Vec training process by running a full training pipeline on our corpus.

The pipeline successfully processed our corpus and trained embeddings. The vocabulary size reflects our choice to keep all words (min_count=1), while the number of training pairs shows how many (center, context) examples were generated after subsampling and dynamic windowing. The final loss indicates the model has converged to a stable state where it can reliably distinguish positive context words from negative samples.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

While our implementation covers the core Word2Vec algorithm, production systems include additional optimizations:

Memory efficiency: The original Word2Vec uses gradient updates directly on shared memory, avoiding the overhead of PyTorch's autograd. For very large vocabularies (millions of words), this matters.

Parallel training: Hogwild-style asynchronous SGD allows multiple threads to update embeddings simultaneously without locks. The occasional stale gradient is acceptable because the learning rate is small.

Large corpus handling: Real corpora don't fit in memory. Production implementations stream data, loading sentences on-the-fly and shuffling at the sentence level rather than the pair level.

Checkpoint and resume: Multi-day training runs need checkpointing. Gensim saves both the model and the vocabulary state for resumable training.

Despite these engineering considerations, the core algorithm remains what we implemented: predict context from center words, and use negative sampling to make it tractable.

Summary

Training Word2Vec effectively requires orchestrating several components:

-

Text preprocessing converts raw text to tokens, with decisions about casing, punctuation, and rare word handling affecting the final embeddings.

-

Subsampling probabilistically removes frequent words, balancing the training signal and speeding up training. Words with frequency above the threshold are aggressively downsampled.

-

Dynamic context windows weight nearby words more heavily by sampling window sizes uniformly. This implicitly captures the intuition that immediate neighbors are more relevant.

-

Negative sampling with the 0.75-power distribution provides a computationally efficient approximation to full softmax, while ensuring rare words have adequate representation in the noise distribution.

-

Linear learning rate decay enables aggressive early exploration followed by stable convergence, with the rate decreasing smoothly from start to finish.

-

Gensim provides a production-ready implementation that handles all these details, while PyTorch implementations offer flexibility for custom modifications.

The training pairs we generate, the negatives we sample, and the learning dynamics we set up all work together to produce embeddings where similar words cluster in vector space. In the next chapter, we'll explore how to evaluate these embeddings and discover the famous word analogy relationships that made Word2Vec famous.

Key Parameters

Understanding Word2Vec's hyperparameters helps you tune the model for your specific corpus and use case.

| Parameter | Typical Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

vector_size | 100-300 | Embedding dimension. Larger values capture more nuance but require more data and computation. 300 is common for general-purpose embeddings. |

window | 5-10 | Context window size. Smaller windows (2-5) capture syntactic relationships; larger windows (5-15) capture topical similarity. |

min_count | 5-10 | Minimum word frequency threshold. Words appearing fewer times are excluded. Higher values reduce vocabulary size and noise. |

negative | 5-20 | Number of negative samples per positive pair. 5-10 works well for large corpora; 15-20 for smaller datasets. |

alpha | 0.025 | Initial learning rate. Skip-gram typically uses 0.025; CBOW uses 0.05. |

min_alpha | 0.0001 | Minimum learning rate at the end of training. |

epochs | 5-15 | Number of training passes over the corpus. More epochs help with smaller datasets. |

sg | 0 or 1 | Architecture selection: 0 for CBOW, 1 for Skip-gram. Skip-gram typically performs better on rare words. |

sample | 1e-5 | Subsampling threshold for frequent words. Lower values discard more frequent words. |

workers | 4-8 | Number of parallel training threads. Set to number of CPU cores for optimal performance. |

For most applications, starting with vector_size=100, window=5, min_count=5, and negative=5 provides a reasonable baseline. Increase embedding dimensions and negative samples if you have a large corpus and need higher-quality embeddings.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about training Word2Vec models.

Comments