Learn how perplexity measures language model quality through cross-entropy and information theory. Understand the branching factor interpretation, implement perplexity for n-gram models, and discover when perplexity predicts downstream performance.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Perplexity

You've built an n-gram language model and applied smoothing techniques. Now comes the critical question: how good is your model? Perplexity provides the answer. It's the standard metric for evaluating language models, used everywhere from academic papers to production systems. Understanding perplexity shows not just how to measure model quality, but what it means for a model to "understand" language.

This chapter develops perplexity from first principles. We'll derive it from information theory, connect it to intuitive concepts like "branching factor," implement it from scratch, and explore both its power and its limitations.

The Evaluation Problem

Consider two language models trained on the same corpus. Model A assigns . Model B assigns . Which model is better?

At first glance, Model A seems superior because it assigns higher probability to a grammatical sentence. But this comparison is misleading. Model A might assign high probability to everything, including nonsense like "mat the on sat cat the." Model B might be more discriminating, reserving high probability for truly likely sequences.

We need a metric that rewards models for assigning high probability to actual language while penalizing them for wasting probability mass on unlikely sequences. Perplexity does exactly this by measuring how well a model predicts held-out test data.

The practice of evaluating a model on data it wasn't trained on. This tests whether the model learned generalizable patterns rather than memorizing the training data. The held-out data is called the test set or evaluation set.

Cross-Entropy: The Foundation

To measure how well a language model predicts text, we need a principled way to quantify "prediction quality." This is where information theory provides the perfect framework. The key insight is that prediction and compression are two sides of the same coin: if you can predict what comes next, you can compress it efficiently. Cross-entropy formalizes this connection, and perplexity translates it into an intuitive scale.

Let's build up to perplexity step by step, starting with the most fundamental question: how do we measure uncertainty?

Entropy: Quantifying Uncertainty

Imagine you're playing a word-guessing game. Your friend thinks of a word, and you have to guess it using only yes/no questions. How many questions do you need?

The answer depends on how predictable the word is. If your friend always picks from {"cat", "dog"} with equal probability, you need exactly one question ("Is it cat?"). But if they pick from a thousand equally likely words, you need about 10 questions (since ). This number of questions is exactly what entropy measures.

For a probability distribution over a vocabulary , entropy is:

where:

- : entropy of distribution (measured in bits when using )

- : probability of word

- The sum runs over all words in the vocabulary

The formula might look abstract, but it captures a clear intuition. The term is called the surprisal or information content of word . It measures how many bits of information you gain by learning that occurred:

- A very likely word (say ) has surprisal bit

- An unlikely word (say ) has surprisal bits

- A certain word () has surprisal bits (no surprise!)

Entropy is the expected surprisal: we weight each word's surprisal by how often it occurs and sum up. Rare words contribute more bits because they're more surprising, while common words contribute fewer.

Let's see this in action with a simple two-word vocabulary:

Notice the pattern: when both words are equally likely, entropy is maximal at 1 bit. You need one yes/no question. As one word dominates, entropy drops because the outcome becomes more predictable. When the outcome is certain, entropy is zero: no questions needed, no uncertainty remains.

This gives us our first key insight: entropy measures the inherent unpredictability of a distribution. A good language model should have low entropy on real text because it can predict what comes next.

Cross-Entropy: Measuring Model Mismatch

Entropy tells us about the true distribution, but we don't have access to that. We only have our model's predictions. This is where cross-entropy enters the picture.

Cross-entropy asks: "If the true distribution is , but we use model to make predictions, how many bits do we need on average?" The answer is always at least as many as entropy, and usually more, because our model isn't perfect.

where:

- : cross-entropy of relative to (measured in bits)

- : true probability of word (from the data)

- : model's predicted probability of word

- : the vocabulary (set of all possible words)

- The sum computes the expected number of bits, weighting each word's encoding cost by its true frequency

The key relationship is: . Cross-entropy is always at least as large as entropy. This inequality holds because using the "wrong" distribution for encoding is never better than using the true distribution . The gap between them, called KL divergence, measures exactly how much our model's predictions differ from reality.

Think of it this way:

- Entropy : the minimum bits needed with a perfect model

- Cross-entropy : the bits needed with our actual model

- KL divergence : the "cost" of using an imperfect model

| Model Quality | Entropy H(P) | KL Divergence | Cross-Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect Model | 2.5 bits | 0.0 bits | 2.5 bits |

| Good Model | 2.5 bits | 0.5 bits | 3.0 bits |

| Average Model | 2.5 bits | 1.5 bits | 4.0 bits |

| Poor Model | 2.5 bits | 3.0 bits | 5.5 bits |

| Random Guessing | 2.5 bits | 5.0 bits | 7.5 bits |

In practice, we don't know the true distribution . Instead, we approximate it using the empirical distribution from our test data. If word appears times in a test corpus of words, we estimate:

where:

- : empirical probability of word (the "hat" notation indicates an estimate)

- : count of how many times word appears in the test corpus

- : total number of words in the test corpus

When we substitute this empirical distribution into the cross-entropy formula, something elegant happens. Since each word in the corpus contributes equally to the empirical distribution, the weighted sum simplifies to a simple average:

where:

- : cross-entropy between the empirical distribution and model

- : total number of words in the test corpus

- : the -th word in the test corpus

- : the probability our model assigns to word

In words: cross-entropy is the average negative log probability that our model assigns to each word in the test corpus. Lower is better because it means the model assigned higher probabilities to the words that actually appeared.

Let's compute this for a simple unigram model:

A cross-entropy around 2.7 bits per word indicates moderate predictability. For comparison, a uniform distribution over our vocabulary of about 8 unique words would give bits. Our unigram model does slightly better because it learned that some words (like "the") are more common than others.

The cross-entropy tells us how many bits on average our model needs to encode each word. This number has a concrete interpretation: if we used our model's probabilities to design a compression scheme, each word would require about this many bits on average.

From Cross-Entropy to Perplexity

Cross-entropy is useful, but "2.7 bits per word" doesn't immediately convey how good a model is. Is that good? Bad? It depends on the vocabulary size and the inherent predictability of the text.

Perplexity solves this by converting bits back to a count, specifically the number of equally likely choices. The transformation is simple:

where:

- : perplexity of the model on word sequence

- : cross-entropy between the true distribution and model distribution

Why raise 2 to the power of cross-entropy? Because entropy measures bits, and each bit doubles the number of possibilities. A cross-entropy of 3 bits means equally likely choices; 10 bits means choices.

Expanding this using our practical cross-entropy formula:

where:

- : total number of words in the test sequence

- : the -th word in the sequence

- : model's probability for word (given its context)

Using properties of logarithms, we can derive an equivalent product form. The derivation proceeds as follows:

Step 1: Start with the exponential form and use the property that :

Step 2: Move the inside using :

Step 3: Apply (the sum of logs becomes the log of a product):

This shows that perplexity is the geometric mean of the inverse probabilities. Equivalently, we can write:

where denotes the -th root.

The geometric mean matters here for two reasons. First, unlike the arithmetic mean, it's sensitive to very small probabilities. A single word with near-zero probability will dramatically increase perplexity. If any , then , making . This is exactly what we want: a good language model shouldn't assign tiny probabilities to words that actually occur. Second, the geometric mean is scale-independent: doubling all probabilities would halve perplexity, regardless of the base probability level.

The perplexity of a language model on a test set is the inverse probability of the test set, normalized by the number of words. It can be interpreted as the weighted average number of choices the model faces at each step. Lower perplexity means the model is less "perplexed" by the test data.

For language models that condition on context (like n-gram models), we use conditional probabilities. The formula above assumed each word probability was independent, but real language models predict each word based on its history. The perplexity formula becomes:

where:

- : the test sequence of words

- : the probability of word given all preceding words (the model's prediction)

- : the -th root (geometric mean)

In practice, we work with log probabilities to avoid numerical underflow. When multiplying many small probabilities (each less than 1), the product quickly approaches zero, causing floating-point arithmetic to lose precision. By working in log space, we convert products to sums:

This is numerically stable because we're adding log probabilities (negative numbers around -3 to -15 for typical words) rather than multiplying tiny probabilities (numbers like to ).

Now the interpretation is immediate: a perplexity around 6-7 means the model faces roughly the same uncertainty as choosing uniformly among 6-7 equally likely words at each position. For a simple unigram model on a small corpus, this is reasonable. The model has learned that some words (like "the") are much more common than others.

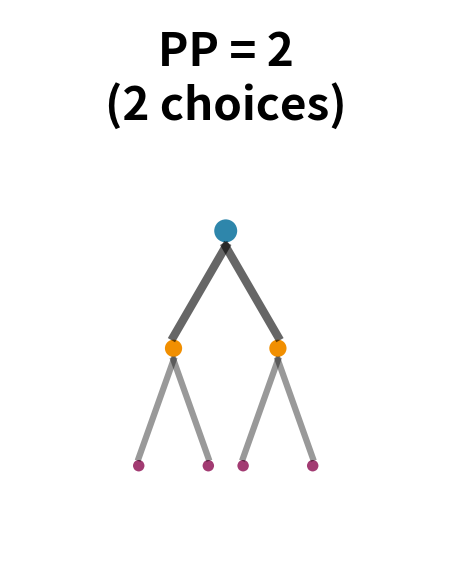

The Branching Factor Interpretation

The most useful insight about perplexity comes from thinking of it as the effective branching factor. Imagine language as a tree where each node represents a word, and branches represent possible next words. At each step, the model must choose which branch to follow.

If all branches were equally likely, the number of branches would be the vocabulary size, potentially tens of thousands. But language isn't uniform. After "the," words like "cat" and "dog" are much more likely than words like "xylophone" or "quasar." A good model exploits this structure to effectively prune the tree.

Perplexity tells you the effective width of this tree. If perplexity is 100, the model is as uncertain as if it were choosing uniformly among 100 words at each step, even though the vocabulary might contain 50,000 words. The model has effectively eliminated 99.8% of possibilities based on context.

This interpretation explains why perplexity is so useful as an evaluation metric. A vocabulary of 50,000 words could theoretically produce perplexity of 50,000 (uniform distribution). A good language model achieves perplexity of 50-200 on typical text, meaning it has effectively reduced the uncertainty by orders of magnitude, from tens of thousands of possibilities to just dozens or hundreds.

Worked Example: Tracing Through the Calculation

Let's make this concrete with a step-by-step calculation. Consider evaluating a bigram model on the sentence "the cat sat." We'll trace through exactly how perplexity emerges from the individual predictions.

Suppose our bigram model gives these probabilities:

| Prediction | Probability | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.20 | "the" is a common sentence starter | |

| 0.10 | "cat" is one of many words following "the" | |

| 0.05 | "sat" is a plausible but not dominant verb | |

| 0.10 | sentences often end after simple verbs |

The probability of the entire sequence is the product of the individual conditional probabilities (using the chain rule of probability):

Substituting our values:

This tiny number () is hard to interpret directly. How "good" is a probability of 0.0001? The answer depends on the sequence length: a longer sequence naturally has lower probability because it's more specific.

Perplexity normalizes by the sequence length, computing the geometric mean of inverse probabilities. With tokens:

Step 1: Compute the inverse of the total probability:

Step 2: Take the -th root to normalize by sequence length:

The model faces an average of 10 equally likely choices at each step. This matches our intuition from the table: some transitions are more predictable (like "the" starting a sentence with probability 0.2, equivalent to choosing among options) while others are harder (like predicting "sat" after "cat" with probability 0.05, equivalent to choosing among options). The geometric mean balances these out to 10.

| Word | Probability P | Inverse 1/P | Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| "the" | 0.20 | 5 | Relatively predictable |

| "cat" | 0.10 | 10 | Moderately uncertain |

| "sat" | 0.05 | 20 | Most uncertain |

| "" | 0.10 | 10 | Moderately uncertain |

| Geometric Mean | - | 10.0 | = Perplexity |

Both methods give identical results, confirming our formulas are consistent. The log probability method is preferred in practice because it avoids numerical underflow. When computing products of many small probabilities, the result can become so small that floating-point arithmetic loses precision. Summing log probabilities keeps the numbers in a manageable range.

Bits Per Character and Bits Per Word

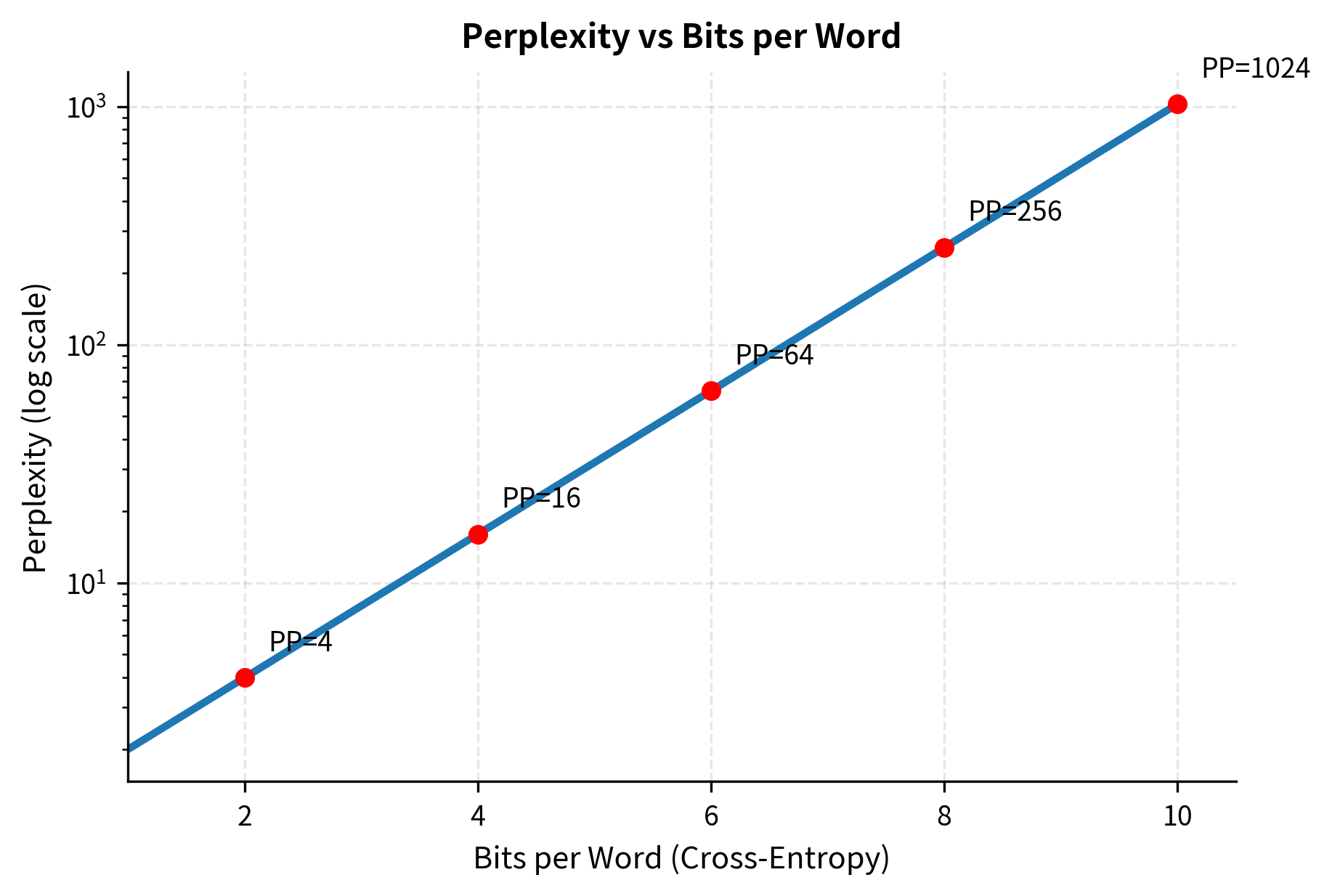

Perplexity can be expressed in different units depending on what you're predicting. Since perplexity and cross-entropy are related by , we can also report results directly as cross-entropy (bits).

Bits per word (BPW): This is the cross-entropy when predicting words. Since , we have . A perplexity of 100 corresponds to bits per word.

Bits per character (BPC): When predicting characters instead of words, we use bits per character. Character-level models typically achieve 1-2 BPC on English text (corresponding to perplexity of 2-4 per character).

The relationship between word-level and character-level metrics depends on average word length. If the average word has characters, a rough approximation is:

where:

- : bits per character (cross-entropy at character level)

- : bits per word (cross-entropy at word level)

- : average word length in characters

- The accounts for the space between words (which is also a character to predict)

This approximation assumes the model's uncertainty is distributed roughly uniformly across characters within words. In practice, character-level models often achieve better compression than this formula suggests because they can exploit subword regularities (like common prefixes and suffixes).

The logarithmic scale shows an important pattern: improvements in perplexity become harder as models get better. Reducing perplexity from 1000 to 500 saves the same number of bits as reducing from 100 to 50, but the latter is typically much harder to achieve.

Implementing Perplexity for N-gram Models

Let's build a complete perplexity evaluation system for n-gram language models.

With 9 training sentences, we have a small but workable corpus. The vocabulary of about 20 tokens is typical for such toy examples. Notice how higher-order models have more unique n-grams: the trigram model distinguishes more context patterns than the bigram model.

Now let's evaluate these models on held-out test data.

The results reveal a common pattern: higher-order models achieve lower perplexity when they have enough training data. The bigram model outperforms the unigram model because it captures local word dependencies (like "the cat" being more likely than "the xylophone"). The trigram model may or may not improve further depending on corpus size. With limited data, trigrams suffer from sparsity.

Per-Sentence Perplexity Analysis

Aggregate perplexity hides important details. Let's examine how perplexity varies across individual sentences.

Sentences that closely match training patterns have lower perplexity. Novel combinations increase perplexity because the model is less certain about them. The output above shows this clearly: sentences with familiar bigram patterns (like "the cat sat on the mat") achieve lower perplexity than those with novel word combinations.

Held-Out Evaluation Methodology

Proper evaluation requires careful data splitting. The standard approach uses three sets:

With this split, most data goes to training, a smaller portion to development for tuning, and the rest is held out for final evaluation. The test set remains untouched until we've finalized all model choices.

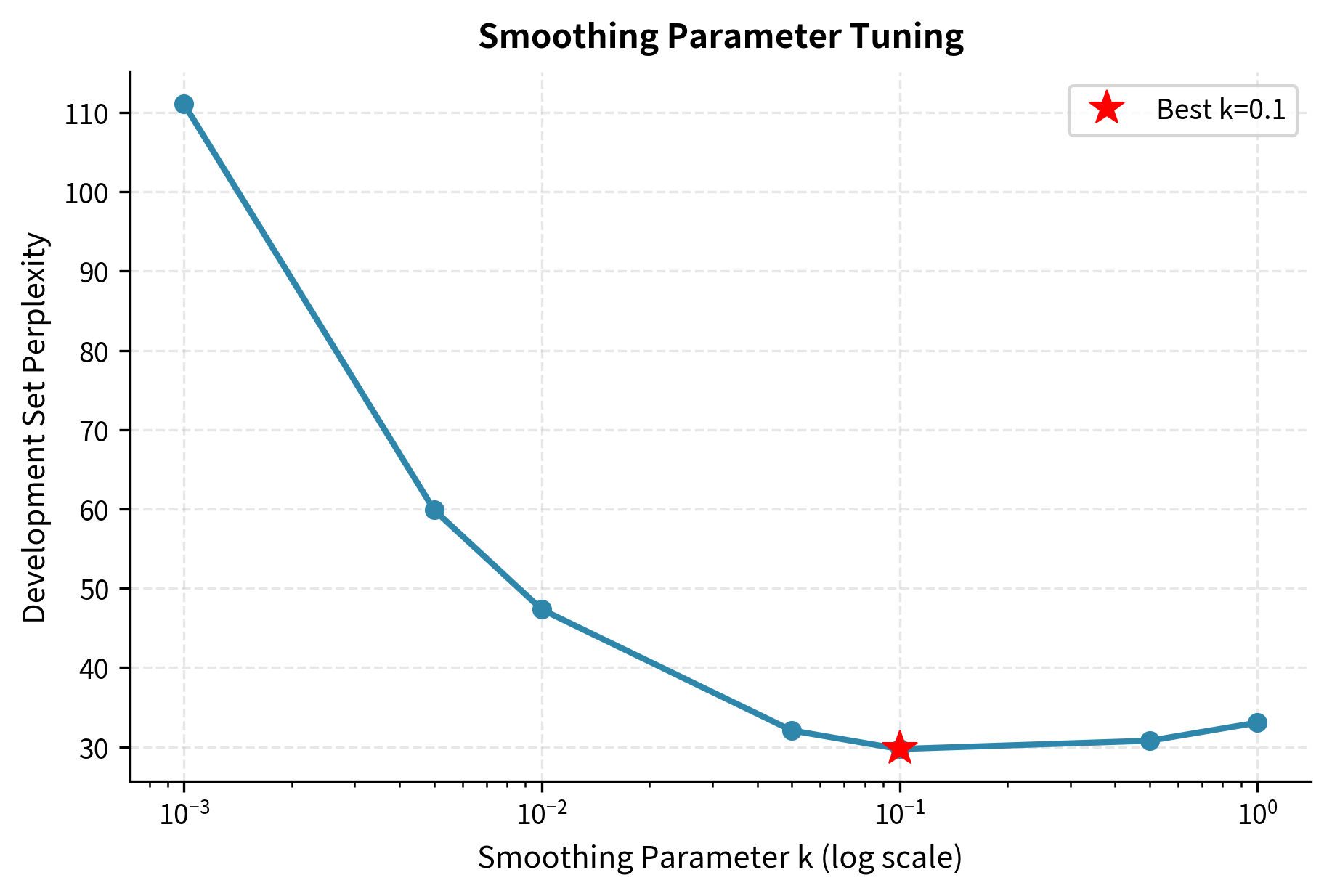

Now let's use the development set to tune the smoothing parameter.

The optimal smoothing parameter balances two competing effects. Too little smoothing (small k) assigns very low probabilities to unseen n-grams, causing high perplexity when the test set contains novel combinations. Too much smoothing (large k) flattens the probability distribution, making all words nearly equally likely regardless of context.

Finally, we evaluate on the test set using the tuned parameter.

The test perplexity may differ from development perplexity because the test set contains different sentences. If test perplexity is much higher, it could indicate overfitting to the development set during tuning.

Comparing Models with Perplexity

Perplexity enables fair comparison between different models, but several caveats apply. For perplexity to be meaningful across models, certain conditions must be met: identical vocabulary, identical test set, and consistent tokenization. Violating these conditions leads to misleading comparisons.

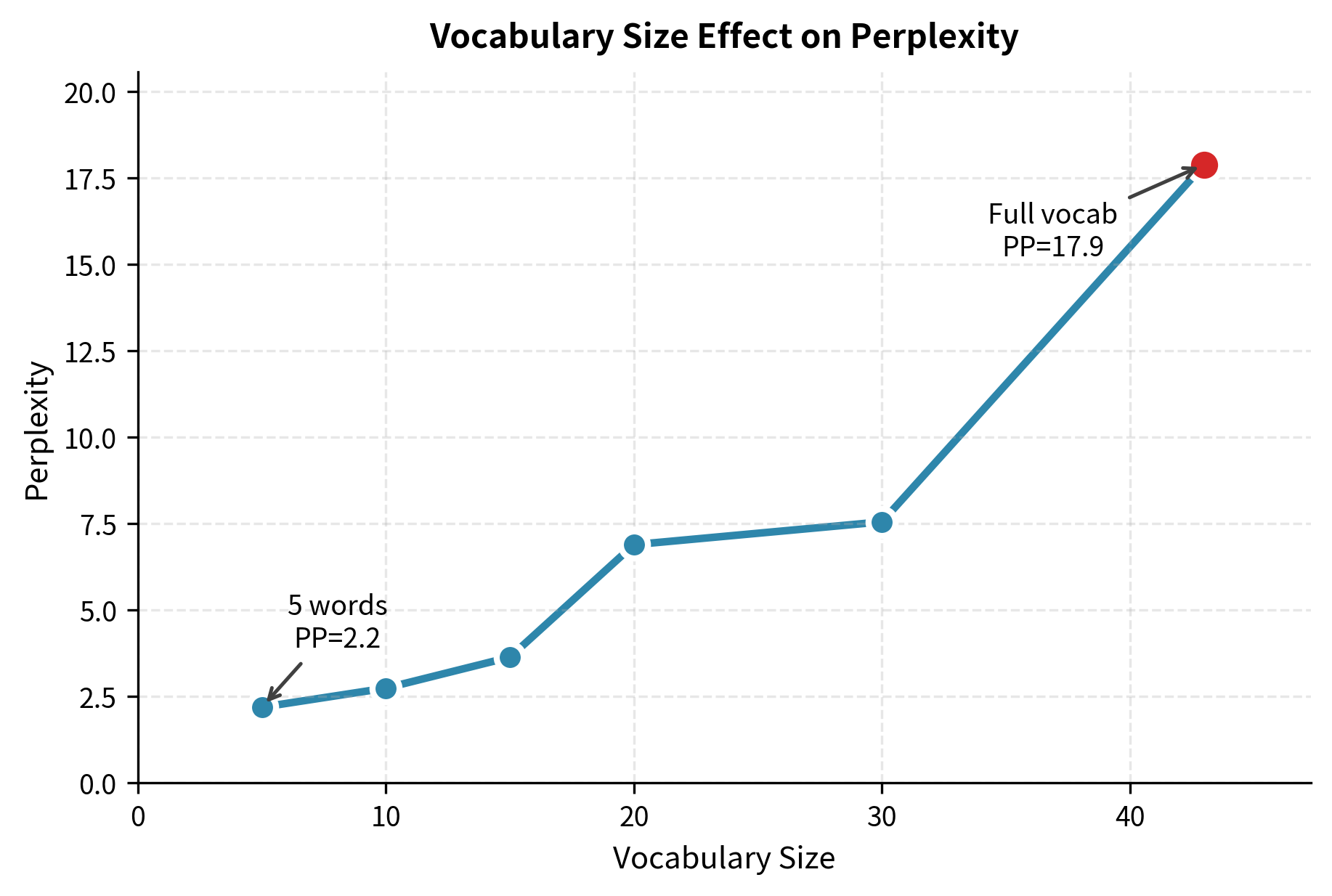

Same Vocabulary Requirement

Models must use the same vocabulary for perplexity to be comparable. A model with a larger vocabulary faces a harder prediction problem because it has more choices at each step.

Smaller vocabularies generally yield lower perplexity because the model has fewer options to choose from at each step. This illustrates why vocabulary size must be controlled when comparing models: a model with a 10-word vocabulary will always outperform one with 10,000 words on raw perplexity, even if the larger-vocabulary model is objectively better.

Same Test Set Requirement

Perplexity scores are only comparable when computed on the same test set. Different test sets may have different inherent difficulty levels.

Statistical Significance

Small differences in perplexity may not be meaningful. Always consider whether improvements are statistically significant, especially when comparing on small test sets.

Perplexity vs Downstream Performance

Perplexity measures how well a model predicts text, but this doesn't always translate to better performance on downstream tasks. The relationship between perplexity and task-specific metrics depends heavily on whether the task fundamentally involves text prediction. Understanding when perplexity is a useful proxy for downstream performance helps guide model selection and evaluation strategy.

When Perplexity Correlates with Task Performance

Perplexity tends to correlate well with tasks that directly involve predicting or generating text:

- Speech recognition: Lower perplexity language models produce better transcriptions

- Machine translation: Language model perplexity correlates with translation fluency

- Text generation: Lower perplexity models generate more coherent text

When Perplexity Doesn't Tell the Whole Story

For other tasks, perplexity may be a poor predictor:

- Sentiment analysis: A model might have excellent perplexity but poor sentiment predictions

- Question answering: Predicting the next word well doesn't mean understanding content

- Named entity recognition: Local word prediction doesn't capture entity boundaries

| Task | Correlation | Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Speech Recognition | 0.9 | Strong |

| Machine Translation | 0.85 | Strong |

| Text Generation | 0.8 | Strong |

| Summarization | 0.6 | Moderate |

| Question Answering | 0.4 | Weak |

| Sentiment Analysis | 0.3 | Weak |

Limitations and Caveats

While perplexity is the standard language model metric, it has important limitations. Factors like out-of-vocabulary words, sentence length, and domain mismatch can significantly affect perplexity scores and their interpretation. Understanding these caveats helps avoid common pitfalls in model evaluation.

Out-of-Vocabulary Words

When the test set contains words not in the training vocabulary, standard perplexity calculation breaks. Solutions include:

- Replace with

<UNK>: Map unknown words to a special token - Character-level models: Avoid the OOV problem entirely

- Open vocabulary: Use subword tokenization (BPE, WordPiece)

The OOV rate here reflects that these test sentences contain words like "elephant," "penguin," and "ocean" that never appeared in our training corpus. Mapping these to <unk> allows perplexity calculation to proceed, but the resulting value is less meaningful because the model treats all unknown words identically regardless of their actual likelihood.

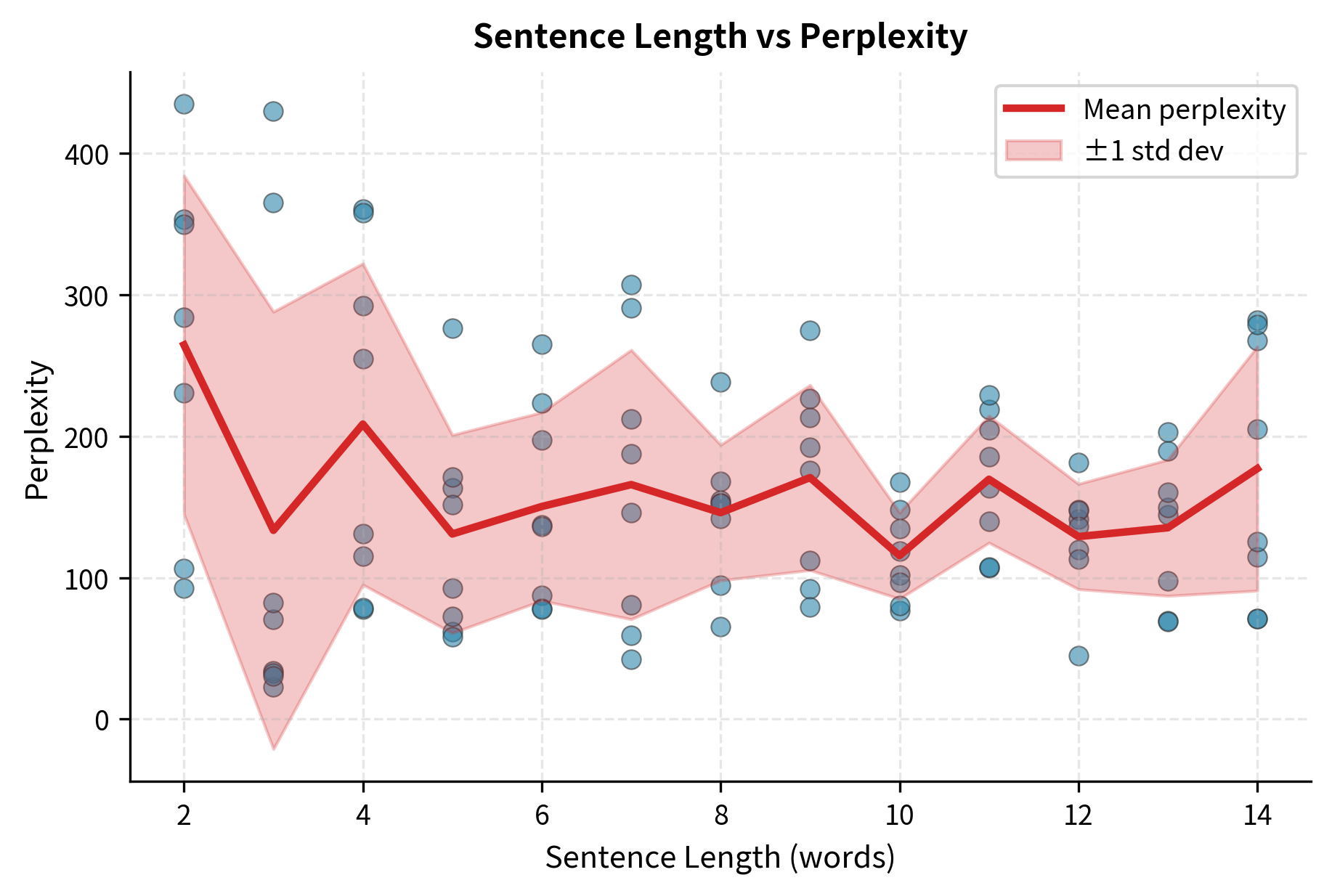

Sentence Length Effects

Perplexity can vary with sentence length. Very short sentences may have artificially low perplexity because they contain only common words. Very long sentences may have higher perplexity due to accumulated uncertainty.

Domain Mismatch

A model trained on news text will have high perplexity on social media text, even if both are "English." This domain mismatch makes cross-domain perplexity comparisons problematic.

The Perplexity Trap

Optimizing solely for perplexity can lead to models that are good at predicting common patterns but poor at handling rare but important cases. A model might achieve low perplexity by always predicting "the" but be useless for real applications.

Historical Context and Modern Usage

Perplexity has been the standard language model metric since the 1980s, when it was used to evaluate early speech recognition systems. Its continued relevance speaks to its utility, but modern usage has evolved.

Classical Era (1980s-2000s)

N-gram models were evaluated primarily by perplexity. A trigram model with Kneser-Ney smoothing might achieve perplexity around 100-200 on news text. Improvements of even 5-10% in perplexity were considered significant.

Neural Era (2010s)

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and LSTMs dramatically reduced perplexity. Models achieved perplexity below 100, then below 50. Perplexity remained the primary metric for comparing architectures.

Transformer Era (2017-present)

Transformer models pushed perplexity even lower. GPT-2 achieved perplexity around 20 on certain benchmarks. However, researchers increasingly recognize that perplexity alone doesn't capture model capabilities like reasoning, factual accuracy, or safety.

| Era | Architecture | Perplexity (PTB) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990s | N-gram (Kneser-Ney) | ~150 | Baseline |

| 2010 | Neural Language Model | ~90 | 40% reduction |

| 2015 | LSTM | ~60 | 33% reduction |

| 2017 | Transformer | ~40 | 33% reduction |

| 2019 | GPT-2 | ~25 | 38% reduction |

| 2020 | GPT-3 | ~20 | 20% reduction |

Summary

Perplexity measures how well a language model predicts held-out text. It's derived from cross-entropy and can be interpreted as the effective branching factor: the average number of equally likely choices the model faces at each prediction step.

Key takeaways:

- Cross-entropy measures the average bits needed to encode test data using the model's probability distribution

- Perplexity equals , converting bits to an interpretable scale

- Lower perplexity means the model assigns higher probability to actual text, indicating better predictions

- Branching factor interpretation: perplexity of 100 means the model is as uncertain as choosing among 100 equally likely words

- Held-out evaluation prevents overfitting by testing on unseen data

- Same vocabulary and test set are required for fair model comparison

- Perplexity doesn't always predict task performance, especially for tasks beyond text prediction

- OOV handling is essential when test data contains words not in training vocabulary

Perplexity remains the standard intrinsic evaluation metric for language models. While it doesn't capture everything important about model quality, it provides a principled, comparable measure of a model's core capability: predicting what comes next in natural language.

Key Parameters

When computing and interpreting perplexity, these factors have the most impact:

| Parameter | Typical Values | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Vocabulary size | 10K-100K words | Larger vocabularies increase perplexity because the model has more choices. Always compare models with the same vocabulary. |

| N-gram order | 2-5 | Higher orders typically reduce perplexity but require more data. Diminishing returns beyond trigrams for most corpora. |

| Smoothing parameter | 0.001-0.5 | Affects perplexity through probability estimates. Tune on development data, not test data. |

| Test set size | 10K+ words | Larger test sets give more stable perplexity estimates. Small test sets may have high variance. |

| OOV rate | < 5% ideal | High OOV rates make perplexity less meaningful. Consider subword tokenization for open-vocabulary evaluation. |

| Log base | 2 or e | Using gives bits; using gives nats. Both are valid but not directly comparable. |

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about perplexity and language model evaluation.

Comments