Learn how the distributional hypothesis uses word co-occurrence patterns to represent meaning computationally, from Firth's linguistic insight to co-occurrence matrices and cosine similarity.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

The Distributional Hypothesis

How do children learn what words mean? They don't consult dictionaries. Instead, they observe words in context, gradually building intuitions about meaning from patterns of usage. The word "dog" appears near "bark," "leash," "pet," and "walk." The word "cat" appears near "meow," "purr," "pet," and "scratch." Through exposure, the brain learns that "dog" and "cat" are related (both are pets) yet distinct (different sounds, different behaviors).

This insight, that meaning emerges from patterns of usage, forms the foundation of distributional semantics. The distributional hypothesis proposes that words appearing in similar contexts have similar meanings. This chapter explores this idea from its linguistic origins to its mathematical formalization, showing how it changed the way computers understand language.

Firth's Insight: You Shall Know a Word by the Company It Keeps

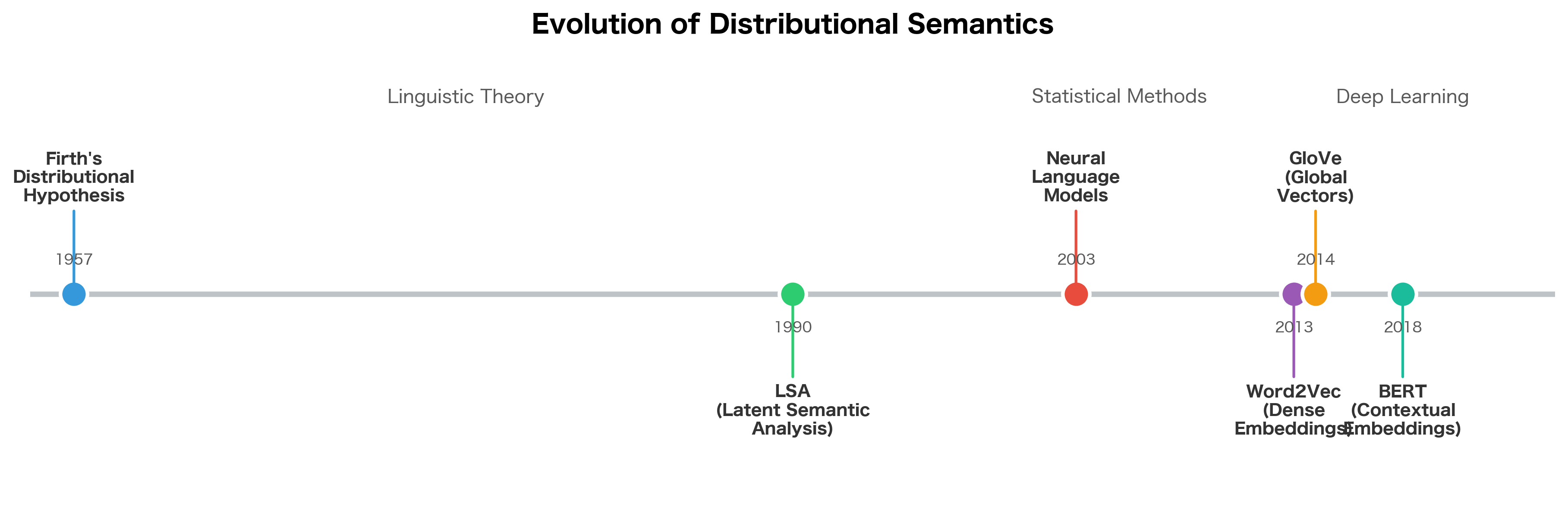

In 1957, British linguist J.R. Firth expressed an idea that would influence computational linguistics for decades: "You shall know a word by the company it keeps." This simple phrase captures the essence of the distributional hypothesis.

The distributional hypothesis states that words occurring in similar linguistic contexts tend to have similar meanings. The more often two words appear in the same contexts, the more semantically similar they are likely to be.

Consider the word "oculist." Most people don't know this word. But if you saw it used in sentences like:

- "I went to the oculist for my annual checkup"

- "The oculist prescribed new glasses"

- "My oculist recommended eye drops"

You'd quickly infer that an oculist is some kind of eye doctor. You learned the meaning not from a definition, but from the company the word keeps. The contexts reveal the semantic neighborhood.

The 100% context overlap demonstrates why these two words must have similar meanings. Both "oculist" and "optometrist" fit identically into vision-related sentence patterns, revealing that they occupy the same semantic role despite being different lexical items. This is the distributional hypothesis in action: Words that can substitute for each other in sentences, filling the same "slots," tend to mean similar things.

The Linguistic Foundation

The distributional hypothesis didn't emerge from computer science. It grew from structural linguistics, where researchers noticed that word meaning could be inferred from distributional patterns alone.

Paradigmatic and Syntagmatic Relations

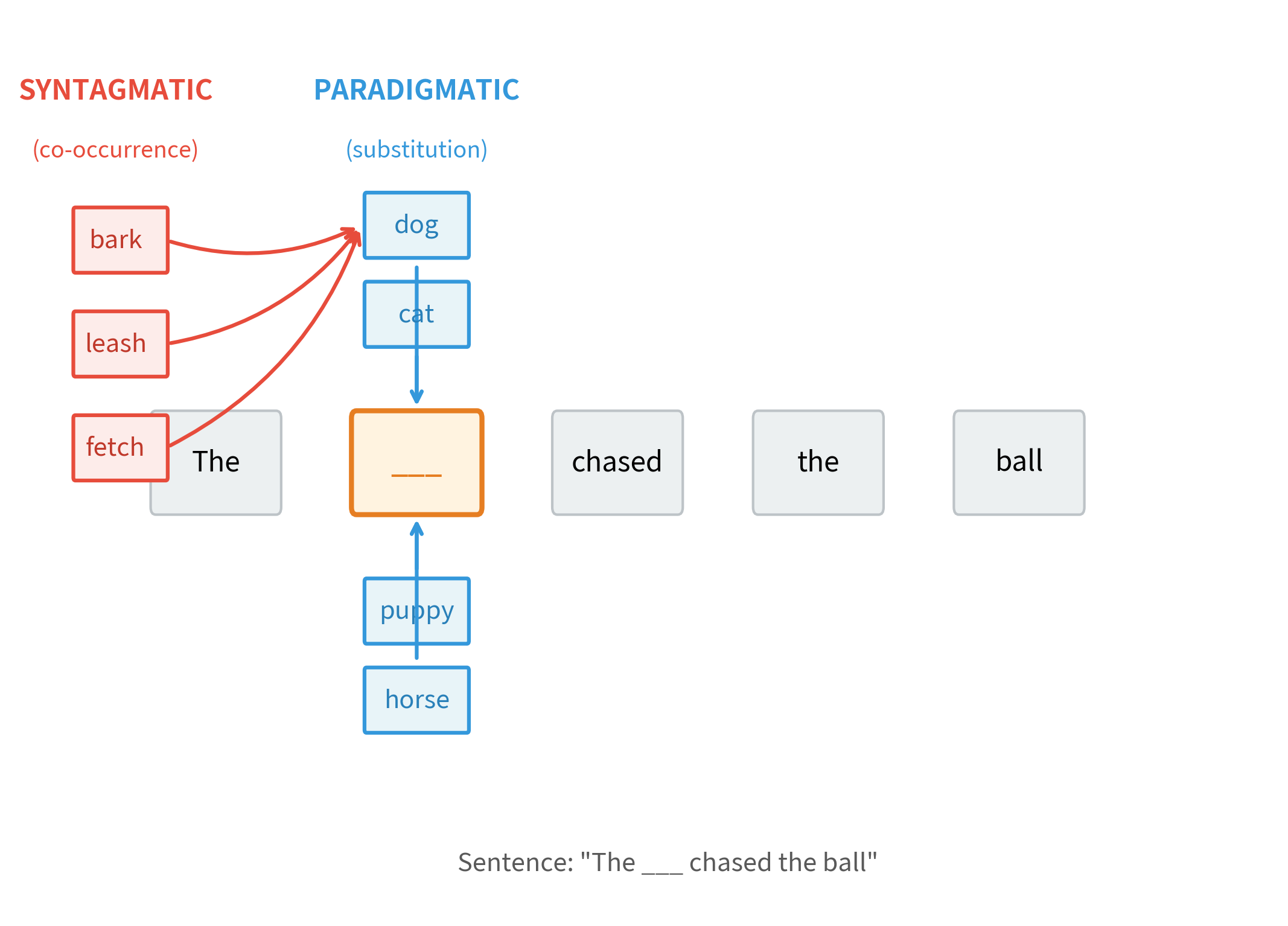

Linguists distinguish two types of relationships between words:

Paradigmatic relations hold between words that can substitute for each other in the same position within a sentence. Words in a paradigmatic relationship belong to the same grammatical category and often share semantic properties. Examples: "cat" and "dog" in "The ___ slept."

Syntagmatic relations hold between words that frequently co-occur in sequence or proximity. These relationships reflect how words combine to form meaningful phrases. Examples: "drink" and "coffee," "strong" and "tea."

The paradigmatic words all share a common role: they can grammatically fill the subject slot in the template sentence. Meanwhile, the syntagmatic associates frequently appear near the word "dog" but wouldn't substitute for it grammatically. Both types of relations contribute to distributional similarity: Words with high paradigmatic similarity (like "dog" and "cat") appear in similar sentence positions. Words with high syntagmatic association (like "dog" and "bark") frequently co-occur nearby.

The Distributional Similarity Intuition

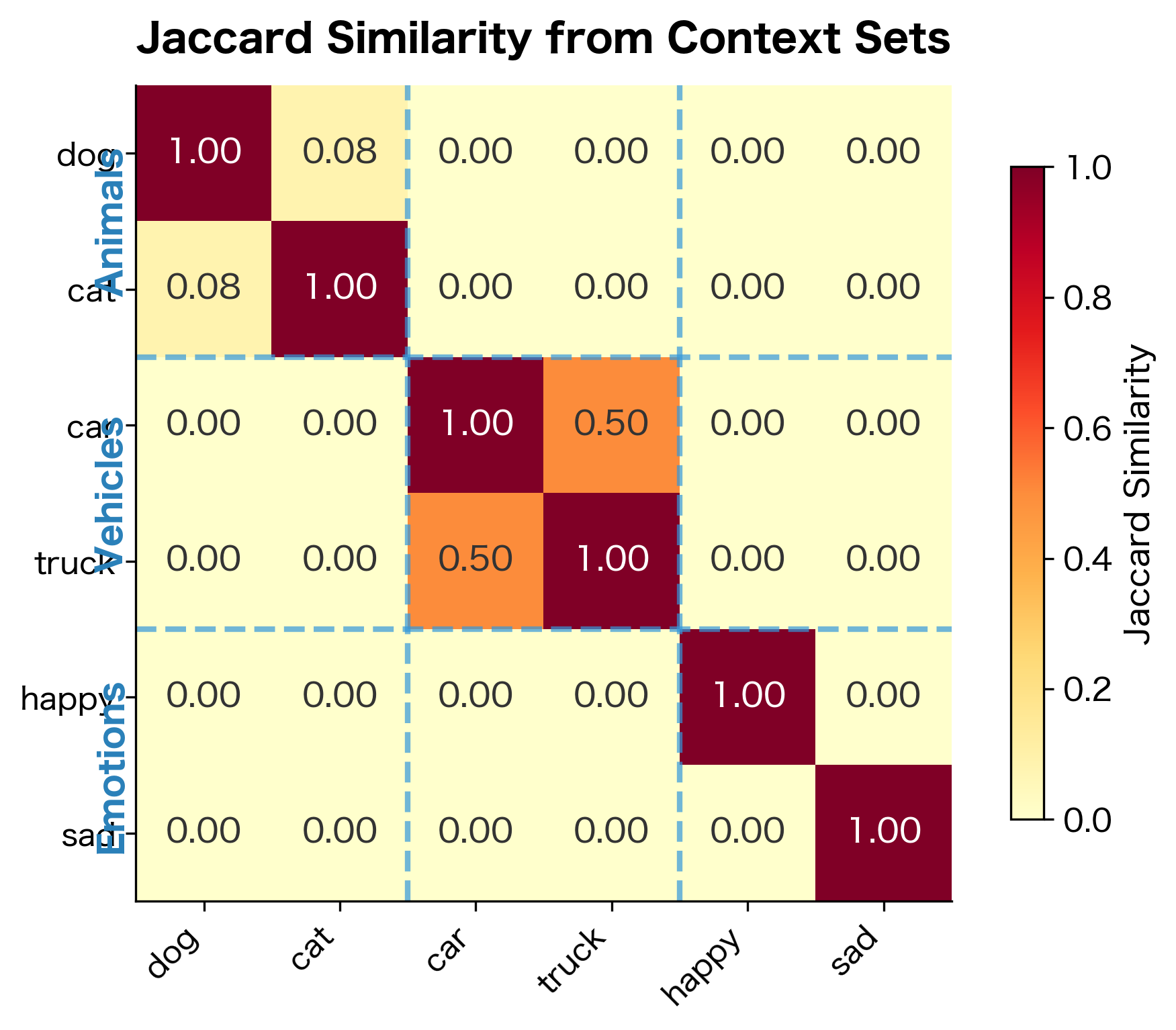

If two words appear in similar contexts, they likely have similar meanings. We can formalize this intuition by representing each word as a set of its context words, then measuring the overlap between these sets.

One simple way to measure set overlap is Jaccard similarity, which computes the ratio of shared elements to total elements:

where:

- : two sets of context words (one for each word being compared)

- : the number of context words shared by both sets (intersection)

- : the total number of distinct context words across both sets (union)

The result ranges from 0 (no overlap) to 1 (identical sets). If "dog" and "cat" both appear near the word "pet," that shared context contributes to their similarity.

The similarity scores align with our intuitions. "Dog" and "cat" share contexts (both are pets), as do "car" and "truck" (both are vehicles). Words from different semantic categories share few contexts and have low similarity.

Context Windows: Defining "Company"

What exactly counts as "context"? The distributional hypothesis requires us to define what it means for words to "appear together." The most common approach uses a context window: a fixed number of words before and after the target word.

A context window defines the span of text around a target word that counts as its context. A window of size includes the words before and words after the target, capturing local co-occurrence patterns.

Window Size Effects

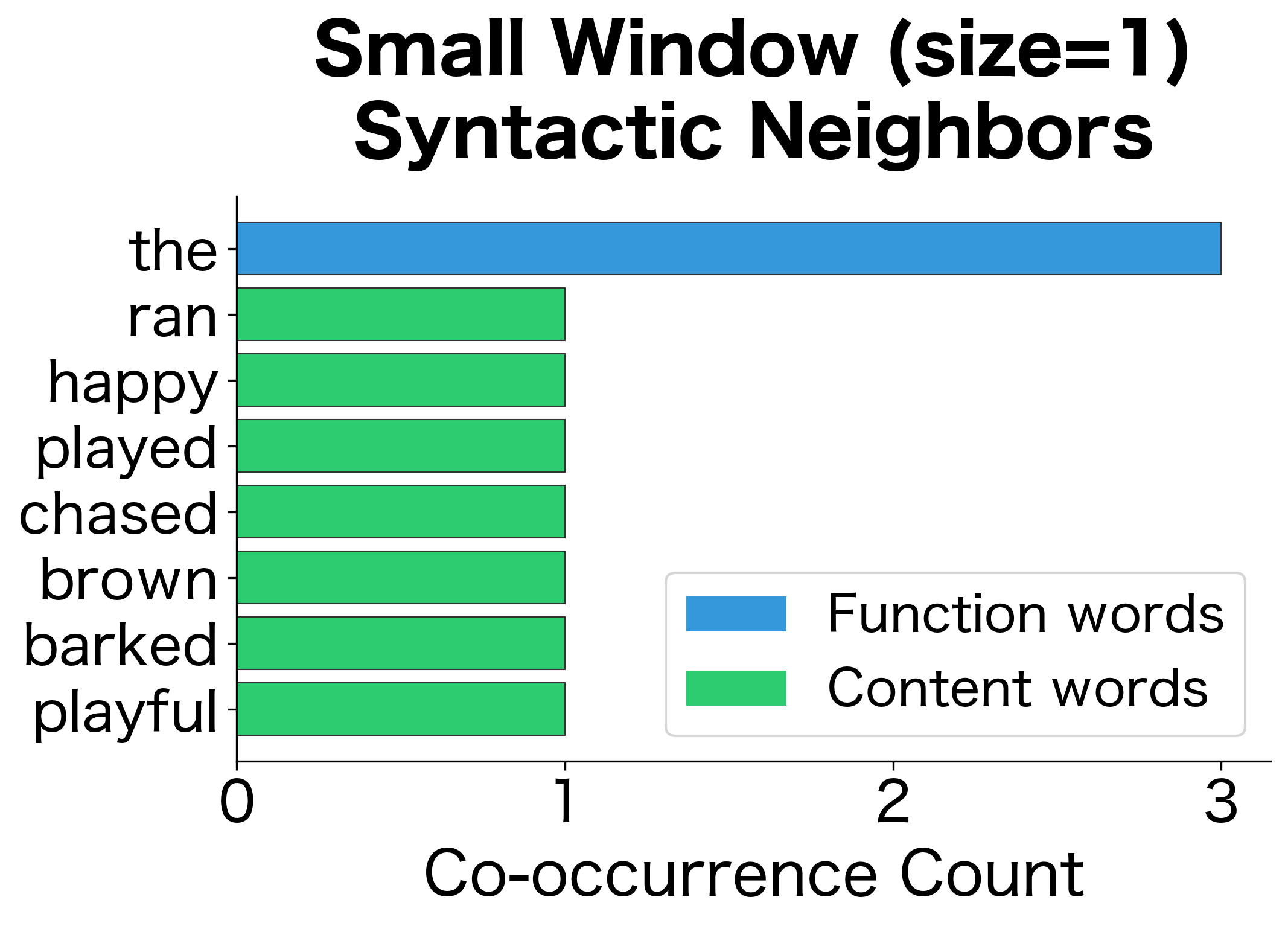

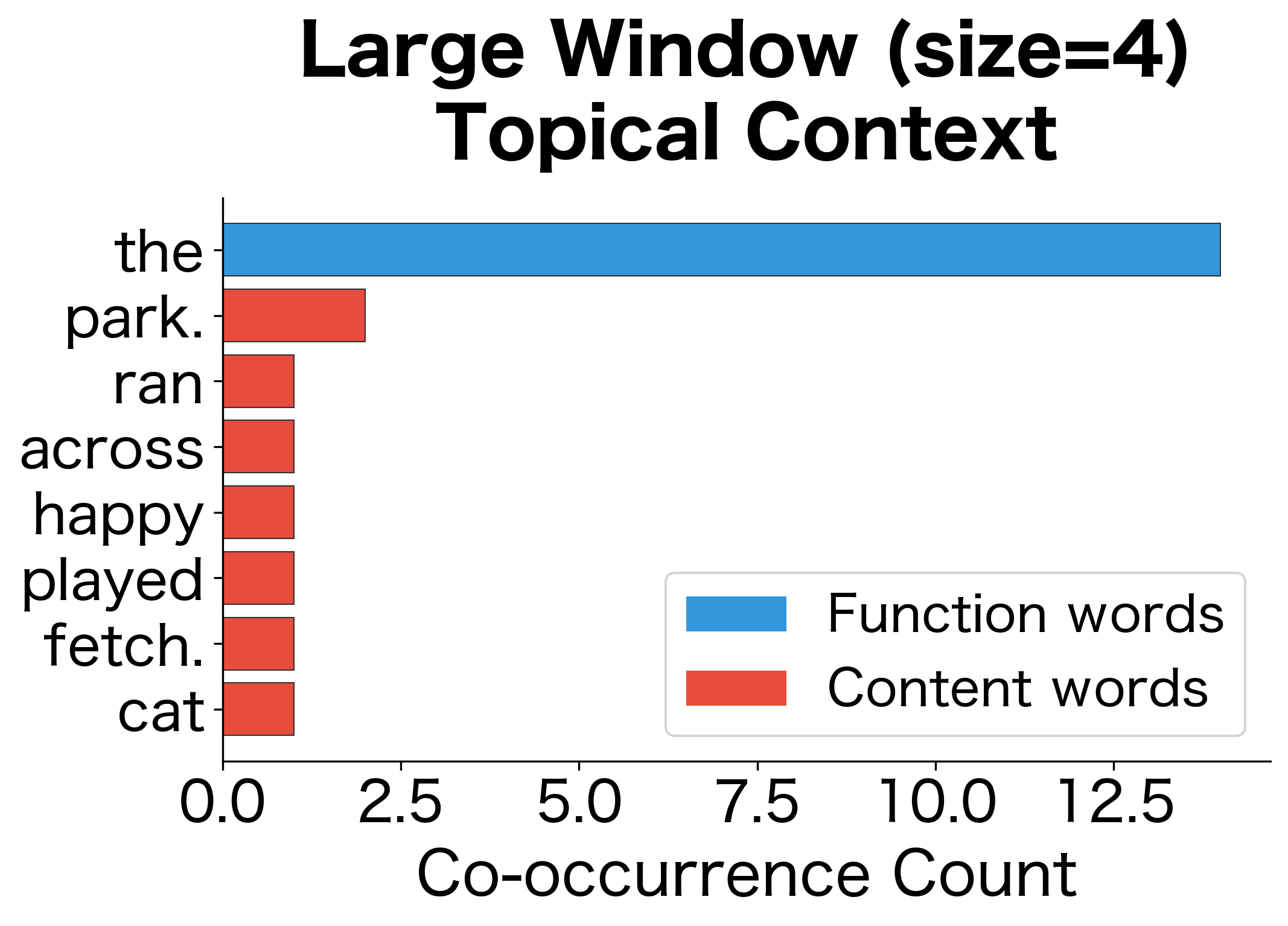

The choice of window size significantly affects what relationships we capture:

- Small windows (1-2 words): Capture syntactic relationships and functional similarity. Words that share small-window contexts tend to be syntactically interchangeable.

- Large windows (5-10 words): Capture topical and semantic relationships. Words that share large-window contexts tend to appear in the same topics or domains.

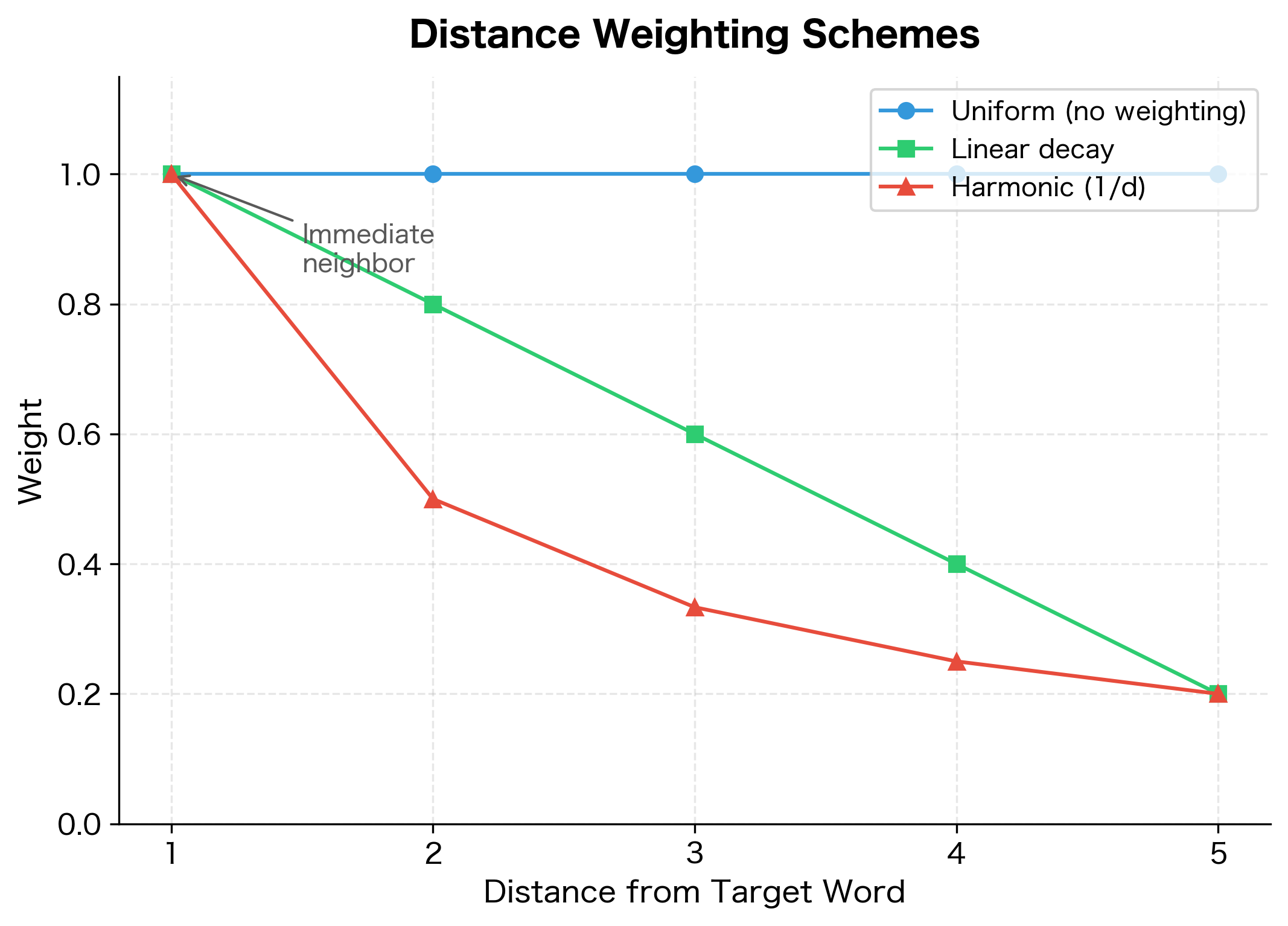

Distance Weighting

Not all context words are equally informative. Words immediately adjacent to the target are more strongly associated than words several positions away. Many distributional models weight context words by their distance from the target.

Distance weighting emphasizes immediate neighbors while still capturing broader context. This often improves the quality of learned representations.

From Contexts to Vectors

We've established that words appearing in similar contexts have similar meanings. But how do we make this intuition computational? The key insight is that we can represent each word's "contextual profile" as a numerical vector, transforming the abstract notion of meaning into something we can measure and compare.

Think of it this way: if you wanted to describe a word's meaning through its usage patterns, you might list all the words that appear near it and how often. "Dog" appears near "bark" 5 times, near "walk" 3 times, near "cat" 2 times, and so on. This list of co-occurrence counts forms a fingerprint of the word's meaning. Two words with similar fingerprints likely have similar meanings.

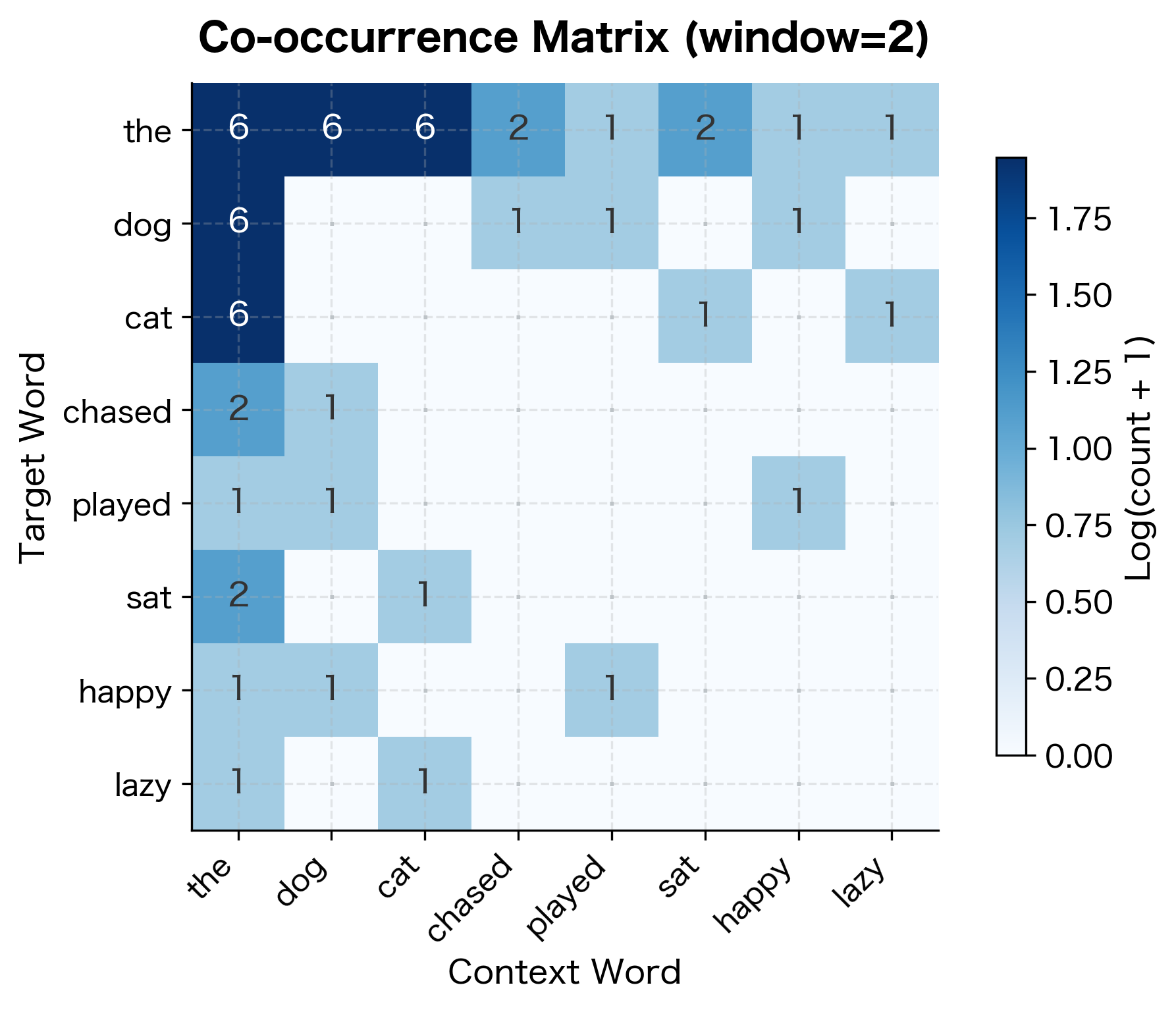

The Co-occurrence Matrix: Capturing Context Numerically

To formalize this intuition, we construct a co-occurrence matrix. This matrix has one row for each word in our vocabulary and one column for each possible context word (which is also the vocabulary). The entry at row , column counts how often word appears near word within our chosen context window.

The construction process works as follows:

- Build the vocabulary: Extract all unique words from the corpus that meet a minimum frequency threshold

- Initialize the matrix: Create a matrix of zeros, where is the vocabulary size

- Scan the corpus: For each word, look at its context window and increment the corresponding matrix entries

- Result: Each row becomes a distributional vector representing that word's contextual associations

Each row of this matrix is now a distributional vector for a word. The vector captures how often that word co-occurs with every other word in the vocabulary. Words with similar vectors should have similar meanings, but how do we measure "similar"?

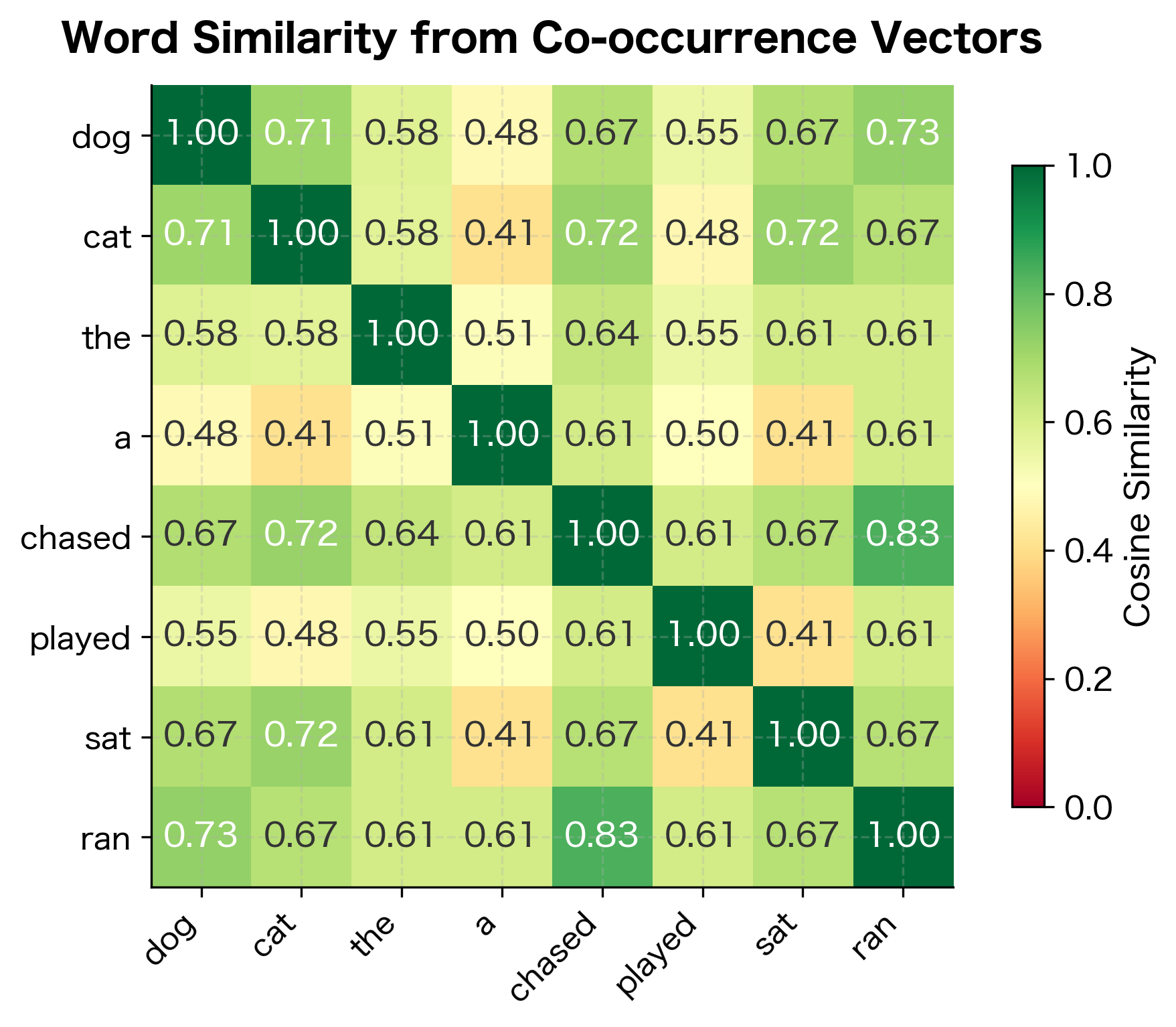

Computing Word Similarity: From Vectors to Meaning

With words represented as vectors in a high-dimensional space, we need a way to measure how "close" two vectors are. The most intuitive approach might be Euclidean distance, but this has a problem: it's sensitive to vector magnitude. A word that appears 1,000 times will have much larger co-occurrence counts than a word appearing 10 times, even if their contextual patterns are identical.

Cosine similarity solves this by measuring the angle between vectors rather than their distance. Two vectors pointing in the same direction have cosine similarity of 1, regardless of their lengths. Perpendicular vectors have similarity 0, and opposite vectors have similarity -1.

The formula captures this geometric intuition:

where:

- : the two word vectors being compared

- : the dot product of the two vectors

- : the magnitudes (lengths) of the vectors

Let's unpack what each component means:

-

The numerator is the dot product. It sums the products of corresponding components. When both vectors have high values in the same dimensions (they co-occur with the same words), the dot product is large.

-

The denominator normalizes by vector magnitudes. The magnitude measures the overall "size" of the vector. Dividing by magnitudes ensures that frequent and rare words can be compared fairly.

Expanding the formula completely with all terms written out:

where:

- : the -th component of vector (co-occurrence count of the first word with the -th vocabulary word)

- : the -th component of vector (co-occurrence count of the second word with the -th vocabulary word)

- : the sum over all dimensions, computing element-wise products

- : the Euclidean norm of

- : the Euclidean norm of

The result ranges from -1 (vectors pointing in opposite directions) to 1 (vectors pointing in the same direction). For co-occurrence vectors, which have only non-negative entries, cosine similarity ranges from 0 to 1.

The results demonstrate the distributional hypothesis in action. Words appearing in similar contexts (sharing high co-occurrence with the same vocabulary items) receive high cosine similarity scores. The mathematical machinery transforms our linguistic intuition into a computable quantity.

A Worked Example: Discovering Word Relationships

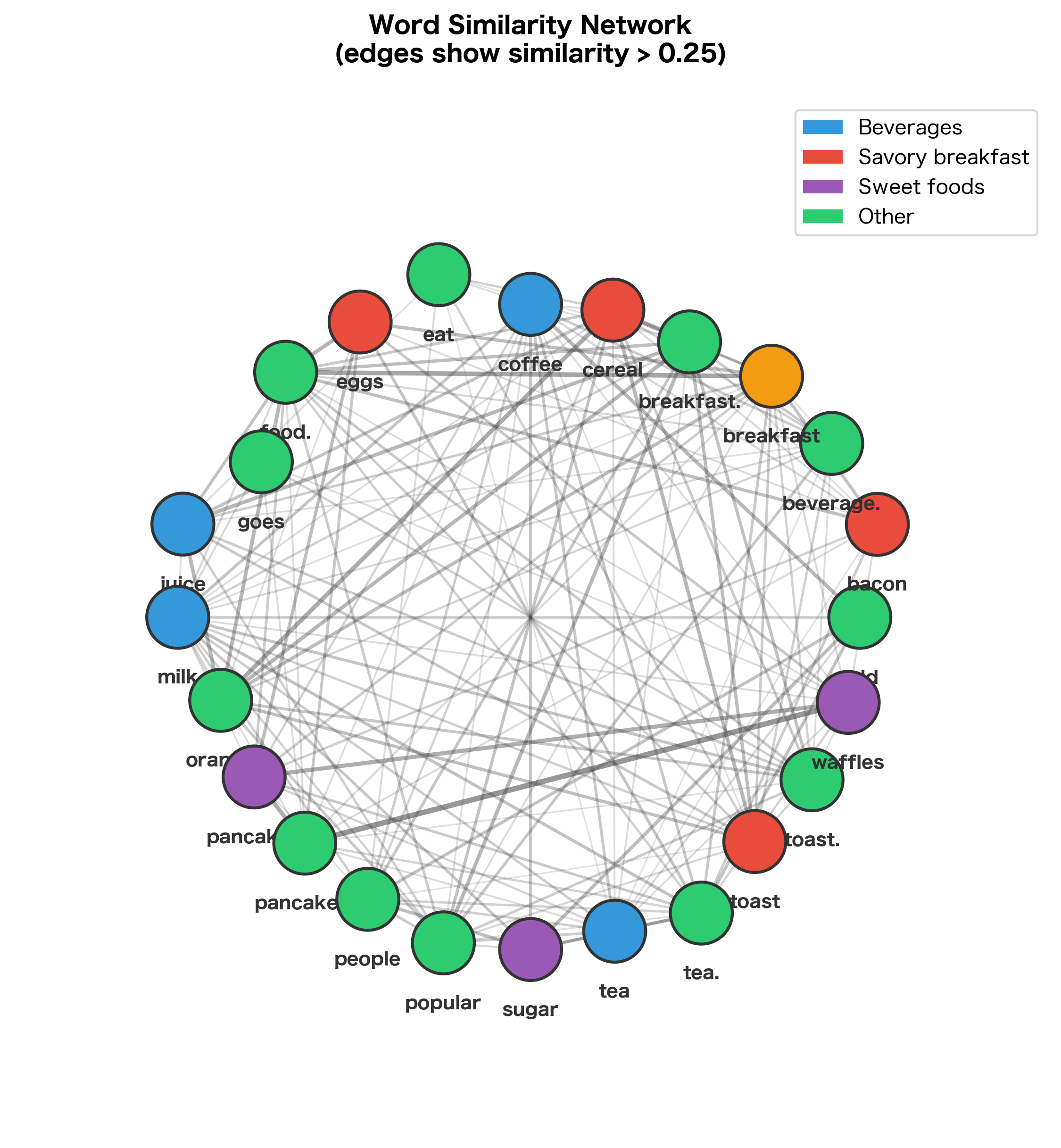

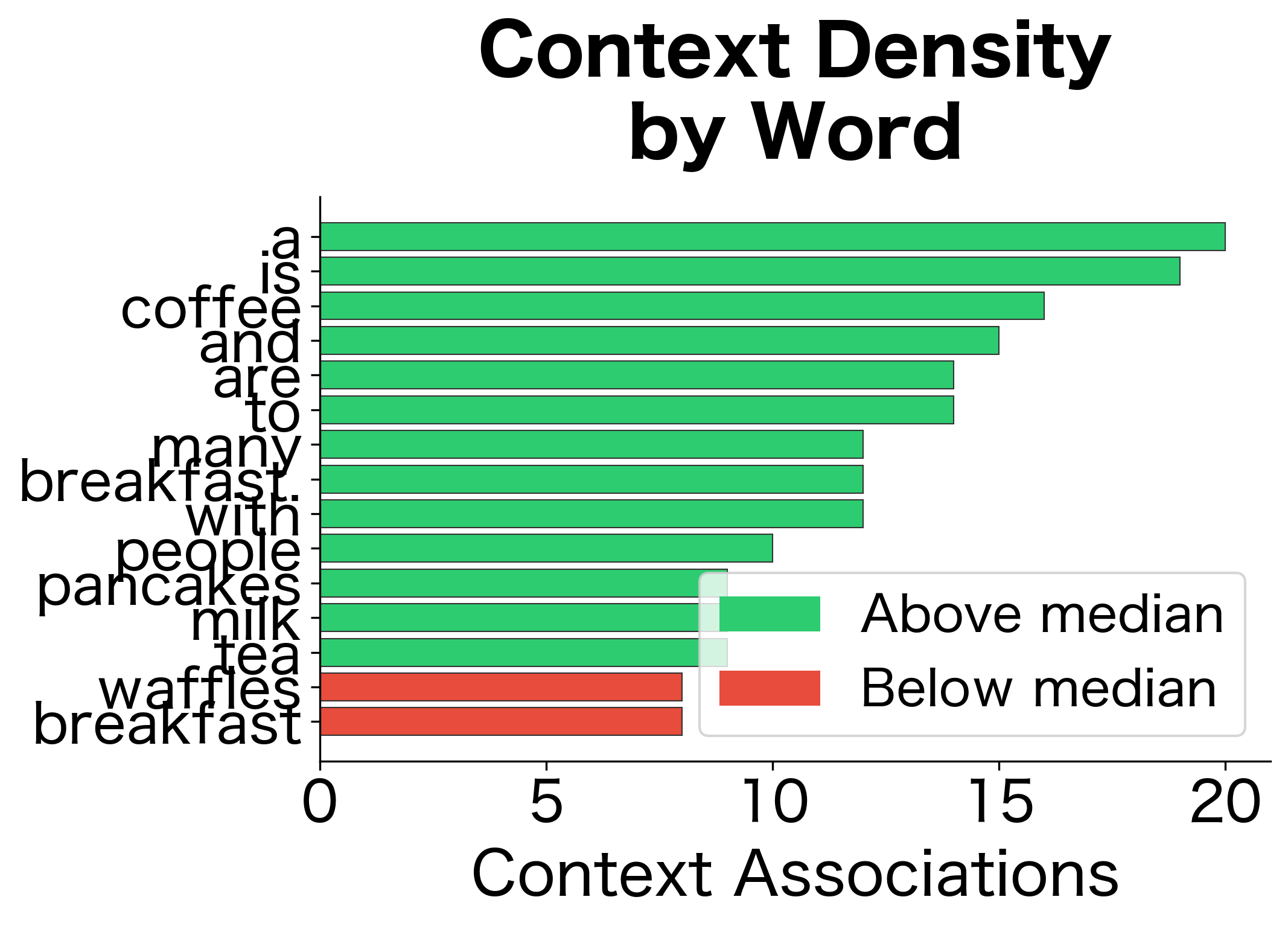

Let's work through a complete example using a larger corpus to see the distributional hypothesis in action.

The distributional analysis correctly identifies that "coffee" and "tea" are similar (both are beverages), and that "breakfast" is associated with food items. These relationships emerged purely from co-occurrence patterns, not from any predefined knowledge.

Limitations of Distributional Semantics

The distributional hypothesis works well in many cases, but it has limitations. Understanding these limitations helps explain why more sophisticated approaches like neural word embeddings were developed.

The Sparsity Problem

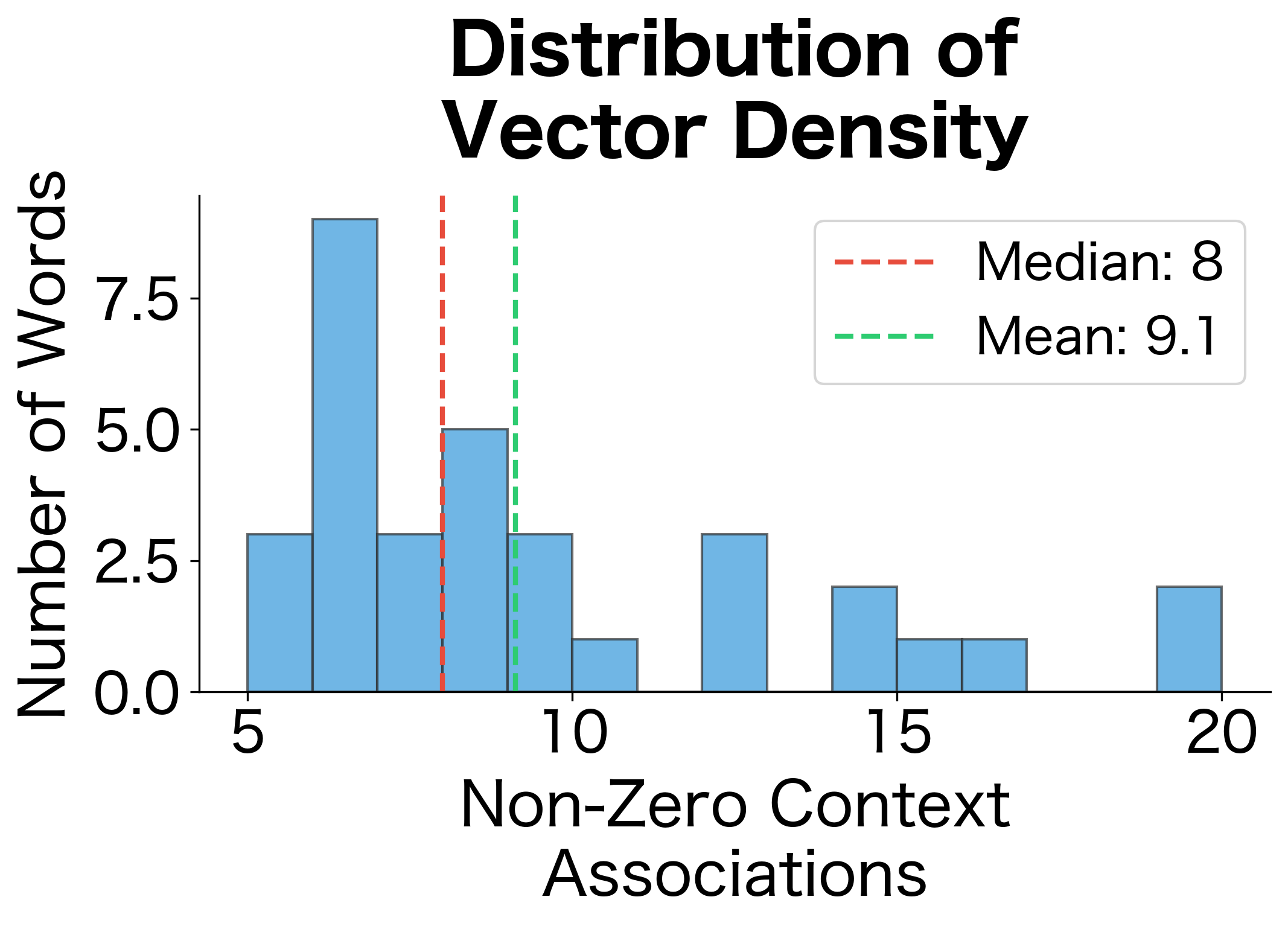

Co-occurrence matrices are extremely sparse. Most word pairs never appear together, even in large corpora. This sparsity makes similarity estimates unreliable for rare words.

This high sparsity level reveals a fundamental challenge: most word pairs in the vocabulary never co-occur, leaving the majority of matrix entries at zero. Words with fewer than 5 context associations have vectors so sparse that similarity calculations become unreliable. This sparsity problem motivates dimensionality reduction techniques that we'll explore in later chapters.

Polysemy and Homonymy

The distributional hypothesis treats each word form as a single unit, but words can have multiple meanings. The word "bank" (financial institution vs. river bank) gets a single vector that mixes both meanings together.

The single "bank" vector conflates contexts from two completely different meanings: financial institutions and river edges. When computing similarity, this mixed vector will show partial similarity to both "money" and "river," potentially misleading downstream applications. Contextual embeddings like BERT address this by generating different vectors for "bank" depending on the surrounding sentence.

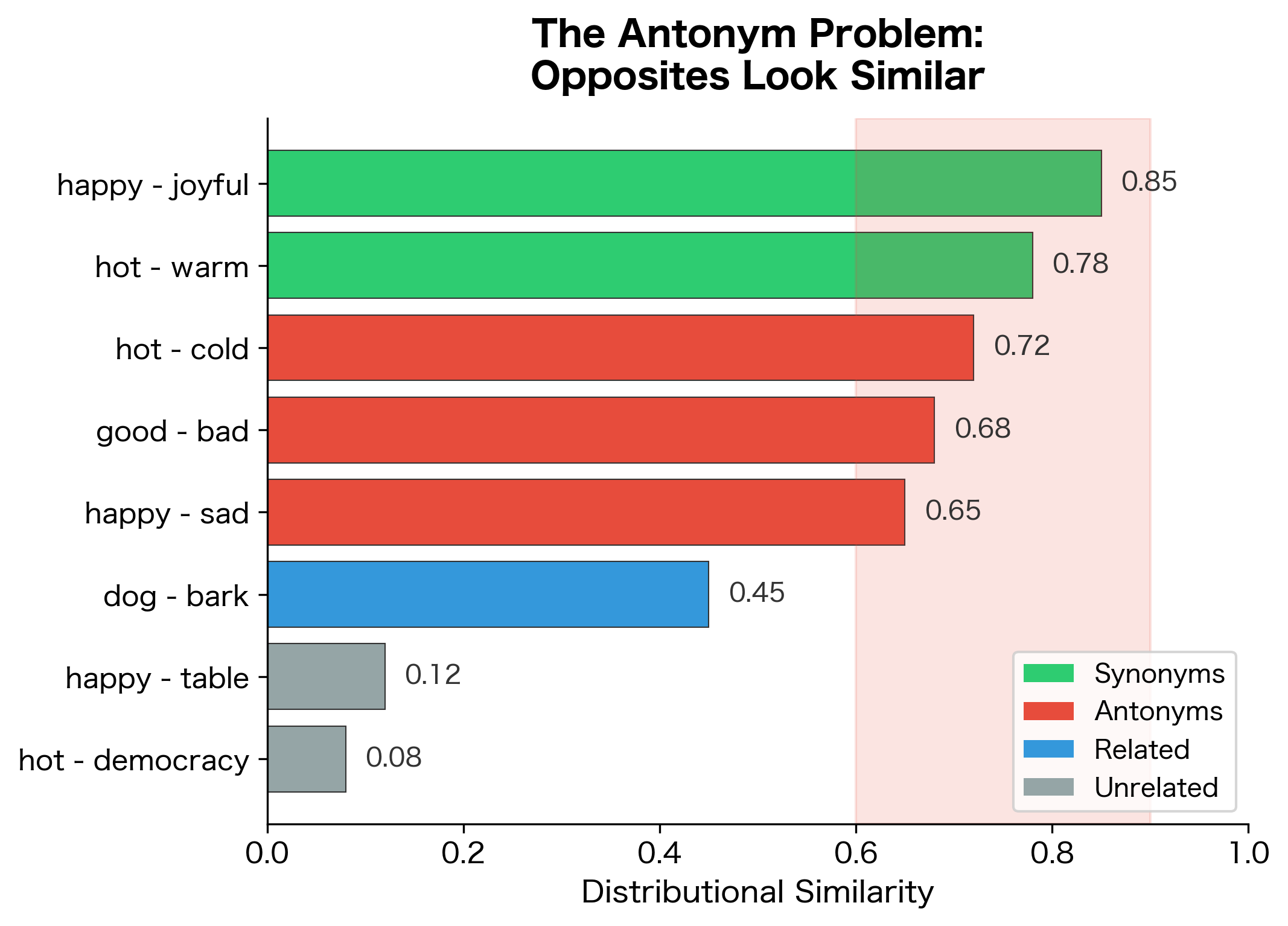

Antonyms Have Similar Distributions

Here's a surprising limitation: antonyms often appear in similar contexts. "Hot" and "cold," "good" and "bad," "happy" and "sad" can substitute for each other in many sentences. Distributional semantics struggles to distinguish opposites from synonyms.

Each template accepts both members of an antonym pair because they share grammatical properties (both are adjectives, both describe the same kind of entity). Distributional semantics captures this syntactic interchangeability but cannot distinguish that the words have opposite meanings. This limitation shows why purely distributional approaches sometimes need supplementary knowledge sources to capture semantic relations like antonymy.

Compositionality

Word meaning often depends on combination. "Hot dog" doesn't mean a warm canine. "Kick the bucket" doesn't involve feet or pails. Distributional semantics at the word level cannot capture these compositional meanings.

Impact on NLP

Despite its limitations, the distributional hypothesis shaped computational linguistics and laid the groundwork for modern NLP:

- Vector space models: The idea that meaning can be represented as points in a high-dimensional space, where distance reflects similarity, remains central to NLP. Modern word embeddings (Word2Vec, GloVe) are direct descendants of distributional semantics.

- Unsupervised learning: Distributional methods learn from raw text without labeled examples. This self-supervised approach, learning structure from data itself, set the stage for pretraining in deep learning.

- Similarity as a primitive: Measuring word similarity enables many applications: information retrieval, question answering, machine translation, and more. The distributional hypothesis provides a clear way to compute similarity.

- Contextual meaning: The insight that context determines meaning points toward contextual embeddings (ELMo, BERT) where the same word gets different representations based on its context.

Key Parameters

When building distributional representations, several parameters significantly affect the quality and characteristics of the resulting word vectors:

window_size: The number of words on each side of the target to include as context.

- Small values (1-2): Capture syntactic relationships and functional similarity. Words that share small-window contexts tend to be syntactically interchangeable (e.g., "dog" and "cat" as nouns).

- Large values (5-10): Capture topical and semantic relationships. Words that share large-window contexts tend to appear in the same domains (e.g., "doctor" and "hospital").

- Typical starting point: 2-5 for most applications.

min_count: Minimum frequency threshold for including words in the vocabulary.

- Low values (1-2): Include rare words, but their vectors may be unreliable due to sparse data.

- Higher values (5-10): More reliable vectors for included words, but rare words are excluded.

- Trade-off: Vocabulary coverage vs. vector quality.

weighting: How to weight context words based on distance from target.

'none': All positions within window weighted equally (weight = 1 for all).'linear': Weight decreases linearly with distance. For a window of size , the weight at distance is . Closer words contribute more.'harmonic': Weight is where is the distance from the target word. Strong emphasis on immediate neighbors (distance 1 gets weight 1, distance 2 gets weight 0.5, etc.).- Recommendation: Linear or harmonic weighting typically improves vector quality.

Similarity metric: How to measure similarity between word vectors.

- Cosine similarity: Most common choice. Measures angle between vectors, ignoring magnitude. Values range from -1 to 1, with 1 indicating identical direction.

- Euclidean distance: Sensitive to vector magnitude. Less common for distributional vectors.

- Jaccard similarity: For binary or set-based representations. Measures overlap between context sets.

Summary

The distributional hypothesis, that words appearing in similar contexts have similar meanings, provides a solid foundation for representing word meaning computationally. From Firth's linguistic insight to modern neural embeddings, this idea has shaped how we teach machines to understand language.

Key takeaways:

- "You shall know a word by the company it keeps": Context reveals meaning, enabling unsupervised learning of semantic representations

- Paradigmatic vs syntagmatic relations: Words can be similar by substitutability (paradigmatic) or by co-occurrence (syntagmatic)

- Context windows define what counts as "company," with smaller windows capturing syntax and larger windows capturing topics

- Distance weighting emphasizes immediate neighbors, improving representation quality

- Vector representations enable mathematical operations on meaning, including similarity computation via cosine similarity

- Limitations include sparsity, polysemy conflation, antonym confusion, and lack of compositionality

The next chapter builds directly on these foundations, showing how to construct and analyze co-occurrence matrices at scale, transforming the distributional hypothesis into a practical computational tool.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about the distributional hypothesis and how context reveals word meaning.

Comments