Discover why traditional word-level approaches fail with diverse text, from OOV words to morphological complexity. Learn the fundamental challenges that make subword tokenization essential for modern NLP.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

The Vocabulary Problem

You've built bag-of-words representations. You've trained word embeddings that capture semantic relationships. But lurking beneath these techniques is a fundamental challenge: what happens when your model encounters a word it has never seen before?

This is the vocabulary problem, and it's more pervasive than you might think. Every time someone coins a new term, makes a typo, uses a technical abbreviation, or writes in a language with rich morphology, traditional word-based models falter. The word "ChatGPT" didn't exist before 2022, yet models trained before then need to process it. The misspelling "reccomend" isn't in any dictionary, yet users type it constantly. The German compound "Bundesausbildungsförderungsgesetz" is a perfectly valid word, yet it will almost certainly be absent from any vocabulary built from a standard corpus.

This chapter explores why word-level tokenization breaks down in practice. We'll examine the explosion of vocabulary sizes, the curse of rare words, and the fundamental tension between coverage and efficiency. By understanding these limitations, you'll see why subword tokenization, which we cover in the following chapters, became essential for modern NLP.

The Out-of-Vocabulary Problem

When Models Meet Unknown Words

Consider a sentiment analysis model trained on movie reviews. It learned representations for words like "excellent," "boring," and "cinematography." Now imagine deploying this model and encountering the review: "This movie was amazeballs! The CGI was unreal."

The word "amazeballs" is almost certainly not in the training vocabulary. What should the model do?

Traditional approaches have three options, none of them good:

-

Replace with a special

[UNK]token: The model treats all unknown words identically, losing crucial information. "Amazeballs" and "terrible" both become[UNK], erasing the distinction between positive and negative sentiment. -

Skip the word entirely: Now the sentence becomes "This movie was ! The CGI was unreal." We've preserved some structure but lost potentially important content.

-

Attempt approximate matching: Maybe "amazeballs" is similar to "amazing"? But this requires additional infrastructure and often fails for truly novel words.

None of these solutions is satisfactory. The [UNK] approach is most common, but it creates a black hole in your model's understanding.

A word is out-of-vocabulary when it doesn't appear in the fixed vocabulary that was constructed during training. OOV words must be handled specially, typically by mapping them to a generic [UNK] token, which discards their unique meaning.

Measuring the OOV Rate

Let's quantify how serious this problem is. We'll train a vocabulary on one text corpus and measure how many words from another corpus are out-of-vocabulary.

Even with this small demonstration, we see a substantial OOV rate. Over half of the test tokens are unknown to our vocabulary built from classic literature. Words like "smartphone," "oled," "hdr," "bluetooth," and "gpu" are completely absent because they represent modern technology concepts that didn't exist when those texts were written. This illustrates how domain shift between training and deployment data creates OOV problems even when vocabulary sizes seem adequate. In real applications with larger vocabularies, the problem persists because language continuously evolves.

The Long Tail of Language

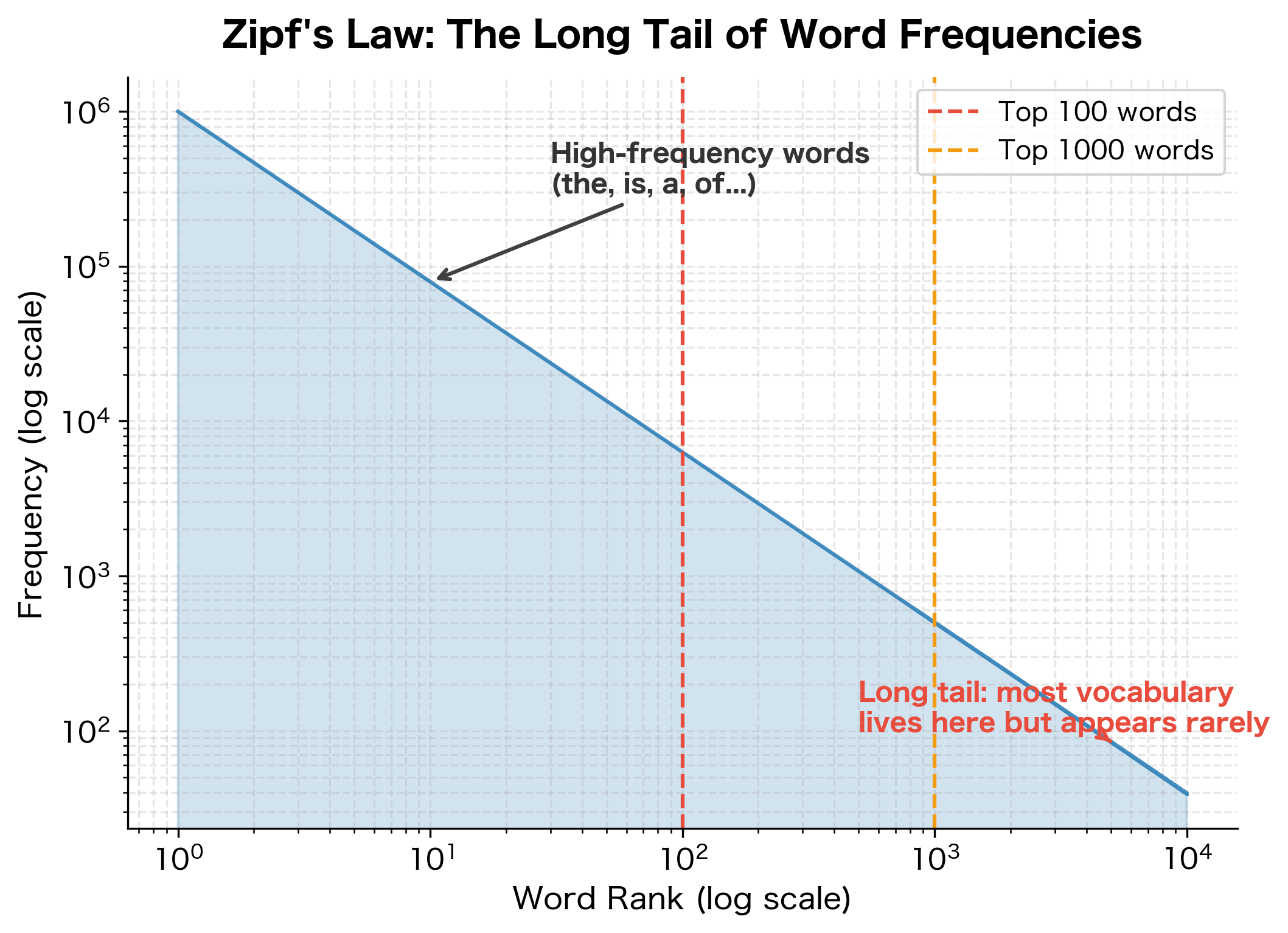

The OOV problem stems from a fundamental property of language: word frequencies follow Zipf's law. A small number of words appear very frequently, while an enormous number of words appear rarely.

The long tail means that no matter how large your training corpus, you'll always encounter new words. Even after seeing billions of words, there will be valid English words, proper nouns, technical terms, and neologisms that never appeared in your training data.

Vocabulary Size Explosion

The Coverage-Size Tradeoff

How large should your vocabulary be? This seems like a simple question, but it reveals a fundamental tension in NLP system design.

A small vocabulary is computationally efficient. The embedding matrix, softmax layer, and any word-based operations scale with vocabulary size. A vocabulary of 10,000 words means 10,000 embeddings to store and 10,000 classes for any word prediction task.

But a small vocabulary means high OOV rates. Users will constantly encounter the [UNK] token, degrading model performance.

A large vocabulary reduces OOV rates but introduces its own problems:

- Memory explosion: Each word needs an embedding vector. With 300-dimensional embeddings, 1 million words requires 1.2 GB just for the embedding matrix.

- Sparse gradients: Rare words appear infrequently during training, so their embeddings receive few gradient updates and remain poorly learned.

- Computational cost: Softmax over millions of classes becomes prohibitively expensive.

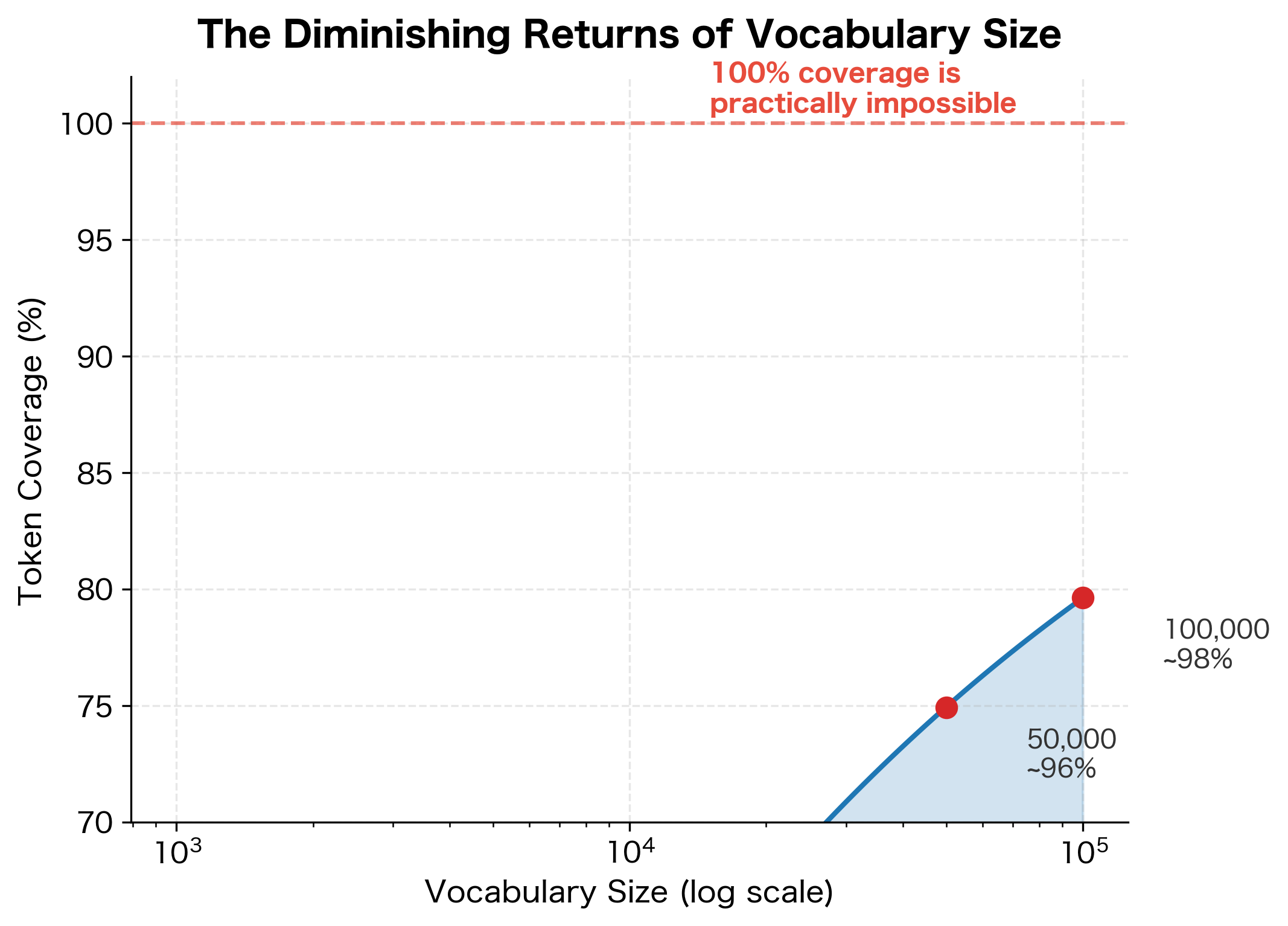

Let's visualize this tradeoff by examining how vocabulary size affects corpus coverage.

The curve reveals a sobering truth: achieving high coverage requires exponentially larger vocabularies. Going from 90% to 99% coverage might require 10x more vocabulary entries. And 100% coverage is essentially impossible because language is infinitely productive.

Real-World Vocabulary Statistics

Let's examine actual vocabulary sizes from popular NLP resources to understand the scale of this problem.

The contrast in scale is striking. Basic English's 850 words require less than a megabyte of storage for embeddings, while pre-trained word vectors like Word2Vec or GloVe contain millions of entries requiring multiple gigabytes. The Google Web 1T corpus represents an extreme case: over 13 million unique word forms, yet even this massive vocabulary doesn't capture every possible word. The memory requirements grow linearly with vocabulary size, with each additional word adding 1.2 KB (300 dimensions × 4 bytes per float). This creates a practical ceiling on vocabulary size, forcing practitioners to choose between coverage and computational efficiency.

The Curse of Rare Words

Poorly Learned Representations

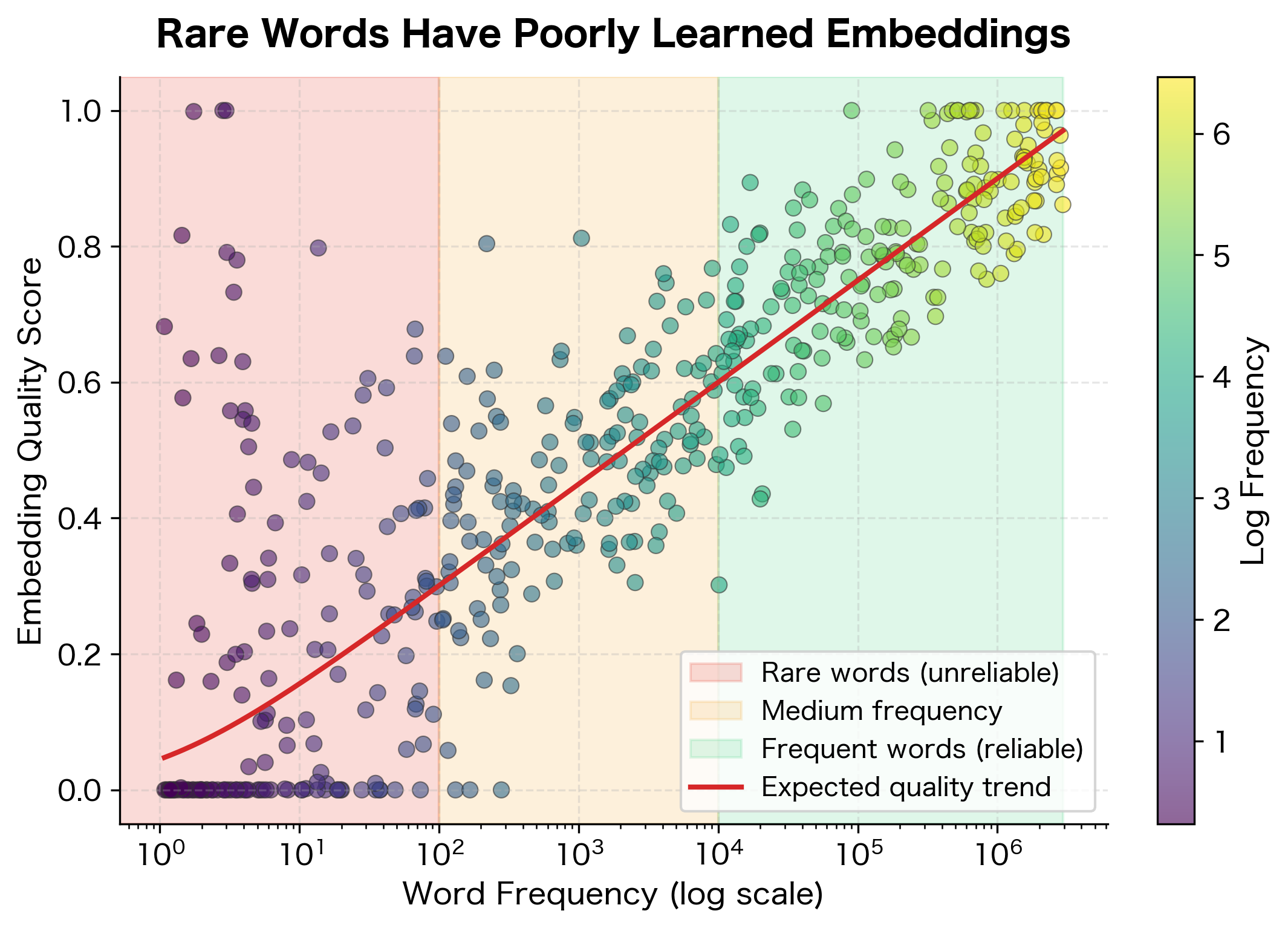

Even when rare words make it into the vocabulary, they suffer from a different problem: insufficient training data. Consider how word embeddings are learned. Each word's representation is updated based on its context. A word that appears 100,000 times receives 100,000 gradient updates, each refining its embedding. A word that appears 10 times receives only 10 updates.

The result is that rare word embeddings are poorly learned. They might be almost random vectors, barely moved from their initialization.

This creates a vicious cycle. Rare words have poor embeddings, which means they contribute little to downstream task performance, which means there's no pressure to improve their representations.

The Minimum Frequency Cutoff

To avoid poorly learned embeddings, most word embedding methods impose a minimum frequency cutoff. Words appearing fewer than, say, 5 times are excluded from the vocabulary entirely.

The table reveals the tradeoff inherent in frequency cutoffs. With min_count=1, all 13 words remain in the vocabulary, but the rarest entries like "linformer" (appearing only once) will have poorly learned embeddings. Raising the cutoff to min_count=5 excludes 3 words, while min_count=100 leaves only 8 words, excluding newer model names like "xlnet" and "electra" entirely. In practice, cutoffs between 5 and 10 are common, balancing embedding quality against coverage. The excluded words become OOV at inference time, replaced with [UNK] and losing their semantic content.

Morphological Productivity

Languages with Rich Morphology

English has relatively simple morphology. Most words have just a few forms: "walk," "walks," "walked," "walking." Other languages aren't so simple.

Consider Finnish, Turkish, or Hungarian. In these agglutinative languages, words are built by stringing together morphemes. A single Finnish word might encode subject, object, tense, aspect, mood, and more. The word "talossanikinko" means "also in my house, I wonder?" packed into a single token.

German famously allows compound nouns: "Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz" is a real word meaning a law about beef labeling supervision delegation. While extreme, such compounds are productive and regularly coined.

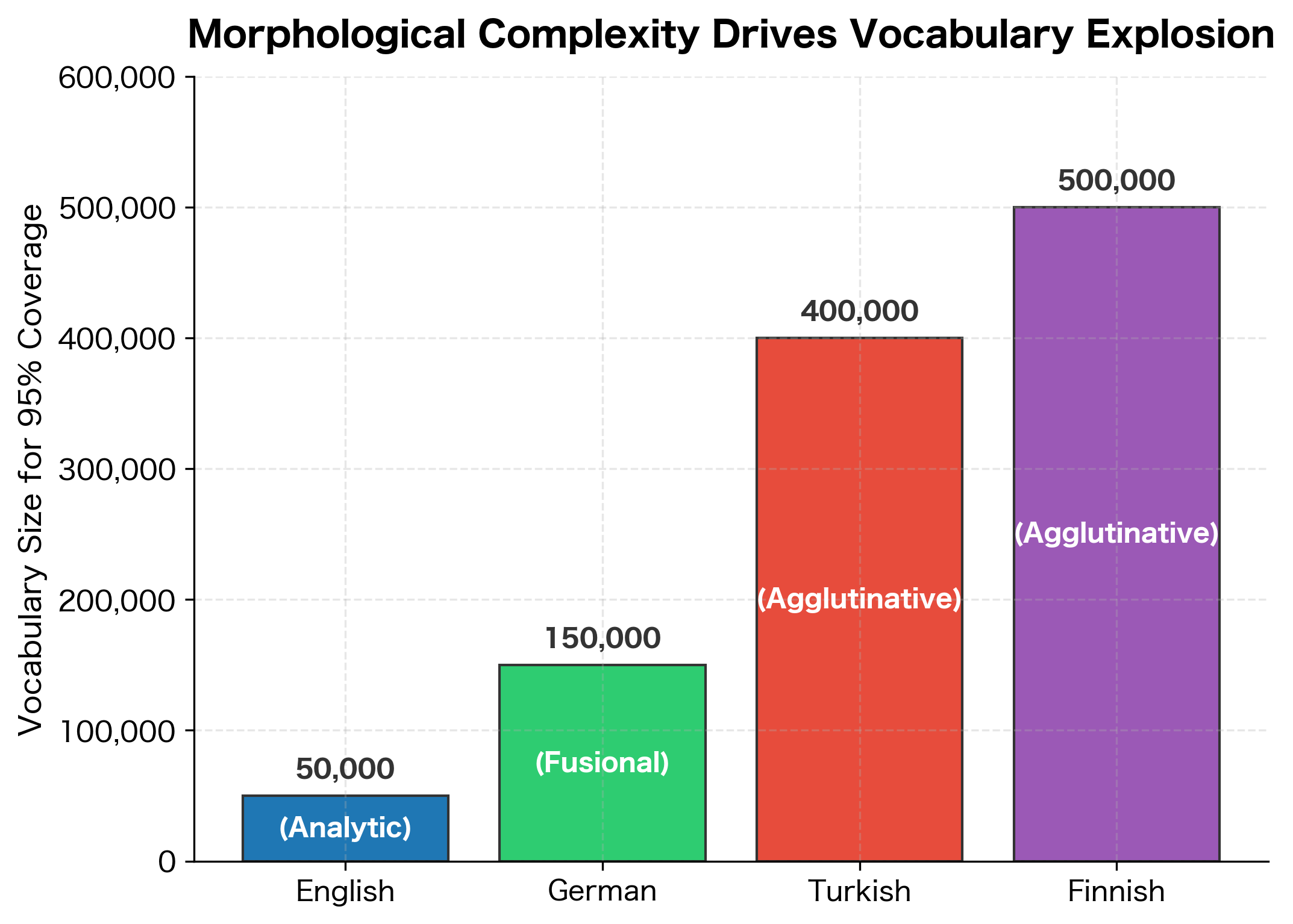

For these languages, word-level vocabularies explode. Every combination of morphemes creates a new vocabulary entry, even though the underlying meaning is compositional.

These examples demonstrate how agglutinative languages build words by attaching morphemes. In Finnish, the root "talo" (house) gains suffixes for location (-ssa), possession (-ni), emphasis (-kin), and question (-ko). Each combination creates a distinct vocabulary entry, even though a native speaker would instantly parse the components. Similarly, German compounds chain nouns together, and Turkish systematically adds suffixes for plurality, possession, and case. A word-level vocabulary would need separate entries for each form, despite their compositional nature.

The Vocabulary Explosion in Morphologically Rich Languages

The combinatorial nature of morphology causes vocabulary explosion. Where English might have 50,000 common word forms, Turkish or Finnish might have millions of valid word forms, most of which any individual speaker has never seen but would instantly understand.

Technical and Domain-Specific Text

The Challenge of Specialized Vocabulary

NLP systems increasingly process technical text: code, scientific papers, medical records, legal documents. Each domain brings its own vocabulary challenges.

Code and Programming:

- Variable names:

getUserById,XMLHttpRequest,__init__ - Mixed formats:

camelCase,snake_case,SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE - Special characters:

!=,->,::,@property

Scientific Text:

- Chemical formulas: CH₃COOH, C₆H₁₂O₆

- Gene names: BRCA1, TP53, CFTR

- Technical terms: "phosphorylation," "eigendecomposition"

Medical Text:

- Drug names: "hydroxychloroquine," "acetaminophen"

- Conditions: "atherosclerosis," "thrombocytopenia"

- Abbreviations: "bid" (twice daily), "prn" (as needed)

The code tokens illustrate how programming conventions pack multiple words into single identifiers. Each camelCase or snake_case token contains meaningful subparts ("get," "user," "by," "id") that would be individually recognized by a general vocabulary, but the combined form is almost certainly OOV. The scientific terms present a different challenge: they're morphologically complex words built from Greek and Latin roots. "Phosphofructokinase" combines "phospho-" (phosphate), "fructo-" (fructose), and "-kinase" (enzyme that transfers phosphate groups). General-purpose vocabularies trained on news or web text have no representation for these specialized terms, forcing domain-specific applications to either expand their vocabularies dramatically or accept high OOV rates.

Code Tokenization: A Special Challenge

Code presents unique tokenization challenges. Unlike natural language, code uses explicit conventions like camelCase and snake_case to pack multiple concepts into single tokens.

The splitting functions reveal the compositional structure embedded in programming identifiers. Both getUserById (camelCase) and get_user_by_id (snake_case) decompose into the same four meaningful tokens: ["get", "user", "by", "id"]. Notice how the camelCase splitter handles acronyms like "XML" and "HTML": it keeps them together as single units rather than splitting each uppercase letter. Each resulting component is a common English word that likely exists in any general vocabulary, even though the combined identifier would be OOV. This insight, that complex tokens often contain recognizable subparts, motivates the subword tokenization approach we explore in subsequent chapters.

The Case for Subword Units

The challenges we've examined, OOV words, vocabulary explosion, rare word embeddings, and morphological complexity, all point toward a common solution. Rather than treating words as indivisible units, we can decompose them into smaller, reusable pieces.

Breaking Words into Meaningful Pieces

The vocabulary problem has an elegant solution: stop treating words as atomic units. Instead, break words into smaller pieces that can be combined to form any word.

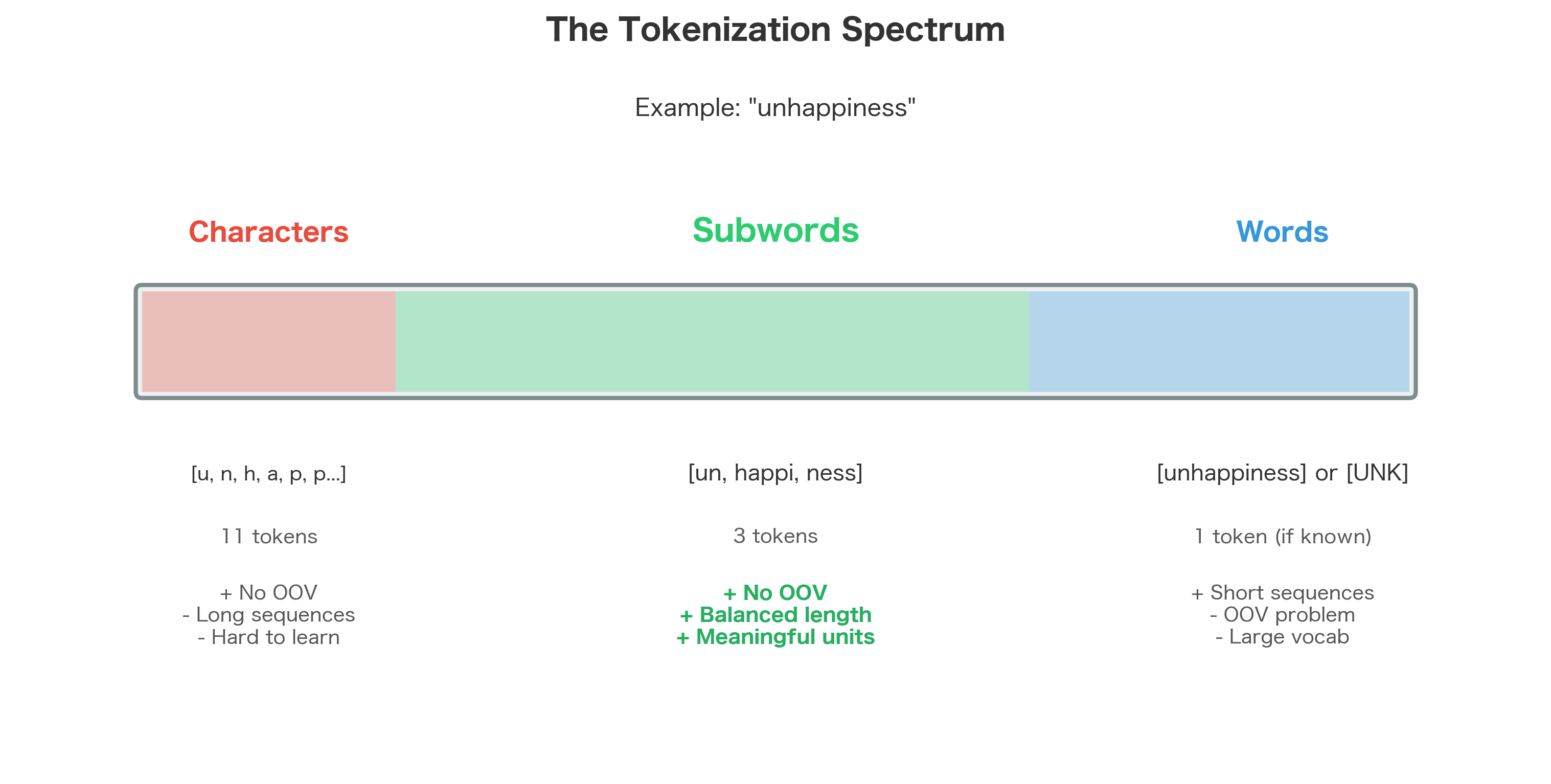

Consider the word "unhappiness":

- As a whole word, it might be rare and poorly represented

- Split into "un" + "happi" + "ness", each piece is common

The prefix "un-" appears in hundreds of words (undo, unfair, unable). The suffix "-ness" appears in thousands (happiness, sadness, kindness). The root "happy" is common. By representing "unhappiness" as a sequence of these pieces, we:

- Eliminate OOV entirely: Any word can be broken into subword units

- Share parameters: "un-" learned from "undo" helps with "unfair"

- Reduce vocabulary size: Thousands of subwords can generate millions of words

- Handle morphology: Compositional words decompose naturally

The decomposition table shows how diverse words break into reusable pieces. Morphologically complex words like "unhappiness" and "internationalization" split at natural boundaries: prefixes, roots, and suffixes. Novel words like "ChatGPT" and "COVID19" decompose into shorter segments that, while perhaps not semantically meaningful individually, are learnable patterns. The reuse statistics reveal the key advantage: the prefix "un" appears in multiple words, so learning its meaning from "unhappiness" transfers to "unbelievable." This parameter sharing dramatically reduces the effective vocabulary size while maintaining complete coverage.

From Characters to Subwords

At one extreme, we could tokenize at the character level. Every word becomes a sequence of characters, and there's no OOV problem: any text is just a sequence of characters from a fixed alphabet.

But character-level tokenization has severe drawbacks:

- Sequences become very long (a 10-word sentence might have 50+ characters)

- The model must learn to compose characters into meaningful units

- Long-range dependencies become harder to capture

Subword tokenization finds the sweet spot. Subwords are longer than characters (capturing more meaning per token) but shorter than words (enabling composition). A typical subword vocabulary might have 30,000-50,000 entries, able to represent any text without OOV.

Looking Ahead: Subword Tokenization Algorithms

The next chapters explore the algorithms that make subword tokenization work. Each takes a different approach to deciding how to split words:

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): Starts with characters and iteratively merges the most frequent pairs. The vocabulary grows bottom-up, with common sequences becoming single tokens.

WordPiece: Similar to BPE but uses a likelihood-based criterion for merging. Used by BERT and many Google models.

Unigram Language Model: Takes a top-down approach. Starts with a large vocabulary and iteratively removes pieces that contribute least to the language model likelihood.

SentencePiece: A framework that can implement BPE or Unigram, treating text as raw bytes rather than requiring pre-tokenization. Enables truly language-agnostic tokenization.

Each algorithm produces a vocabulary of subword units and a procedure for tokenizing new text. The key insight uniting them all: words are not atoms. They can and should be decomposed into smaller, reusable pieces.

Summary

The vocabulary problem arises from a fundamental mismatch between the infinite productivity of language and the finite capacity of NLP models. We've explored several facets of this challenge:

-

Out-of-vocabulary words plague any fixed vocabulary system. New words, rare words, typos, and domain-specific terms all become

[UNK], losing their meaning entirely. -

Vocabulary size creates a tradeoff: Larger vocabularies reduce OOV rates but consume more memory, slow computation, and suffer from poorly-learned embeddings for rare words.

-

Morphologically rich languages make the problem exponentially worse. Agglutinative languages like Finnish and Turkish can form millions of valid word forms from a fixed set of morphemes.

-

Domain-specific text including code, scientific writing, and medical text introduces specialized vocabulary that general-purpose models cannot handle.

-

Subword tokenization offers an elegant solution by breaking words into reusable pieces. A vocabulary of 30,000 subwords can represent any text without OOV, sharing parameters across morphologically related words.

The vocabulary problem taught NLP an important lesson: the word is not the right unit of meaning. In the following chapters, we'll explore the algorithms that learn optimal subword vocabularies and how to tokenize text using them.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding of the vocabulary problem? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about why word-level tokenization breaks down and why subword approaches are needed.

Comments