Learn how SentencePiece tokenizes text using BPE and Unigram algorithms. Covers byte-level processing, vocabulary construction, and practical implementation for modern language models.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

SentencePiece

Introduction

SentencePiece represents a fundamental shift in how we approach text tokenization. Instead of starting with preprocessed text and applying rules-based tokenization, SentencePiece treats raw text as a sequence of bytes and learns optimal subword units directly from the data. This approach eliminates the need for language-specific preprocessing and enables truly multilingual tokenization.

The key insight behind SentencePiece is that we can learn meaningful subword units by treating text as raw bytes and using data-driven algorithms to discover optimal token boundaries. This approach has become the foundation for tokenization in many modern language models, including BERT, ALBERT, and T5.

Technical Deep Dive

SentencePiece operates on the principle that text can be treated as a sequence of Unicode code points, which are then converted to bytes. This byte-level representation allows the algorithm to work across languages without requiring language-specific knowledge.

Byte-Level Processing

At its core, SentencePiece processes text through these steps:

- Unicode normalization: Text is normalized to a consistent Unicode form (typically NFKC)

- Byte encoding: Each Unicode code point is encoded as UTF-8 bytes

- Subword learning: Statistical algorithms learn optimal subword units

- Token mapping: Learned subwords are mapped to token IDs

The key insight is treating whitespace as just another byte pattern. Instead of explicit whitespace tokenization, SentencePiece uses a special prefix character (▁, U+2581) to mark word boundaries during training.

Training Algorithms

How should we decide which subword units to include in our vocabulary? This is the central question that SentencePiece's training algorithms address. We need a principled way to discover token boundaries that capture meaningful patterns in language, patterns that will generalize to new text we haven't seen before.

SentencePiece offers two philosophically different approaches to this problem:

- Bottom-up construction (BPE): Start with the smallest possible units and build up by merging frequent patterns

- Top-down pruning (Unigram): Start with many possible tokens and remove the least useful ones

Both approaches aim to find a vocabulary that efficiently represents the training corpus while generalizing well to new text. Let's explore each in detail.

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE)

BPE takes an intuitive, greedy approach to vocabulary construction. The core insight is simple: if two symbols frequently appear next to each other, they probably represent a meaningful unit that should be treated as a single token.

The intuition: Imagine you're reading a corpus and noticing patterns. You see "ing" appearing constantly at the end of words. You see "th" starting many common words. These frequent co-occurrences suggest natural boundaries where characters "belong together." BPE formalizes this intuition into an algorithm.

Building the vocabulary step by step:

The algorithm begins with the smallest possible vocabulary, individual bytes (or characters). From this minimal starting point, it iteratively discovers larger units:

- Initialize: Start with all unique bytes/characters as the vocabulary

- Count: Scan the corpus and count how often each pair of adjacent tokens appears

- Merge: Take the most frequent pair and combine them into a new token

- Repeat: Continue until the vocabulary reaches the target size

At each iteration, BPE identifies the pair of adjacent tokens with the highest frequency across the corpus:

where:

- : a pair of adjacent tokens in the current vocabulary

- : the number of times tokens and appear consecutively in the corpus

- : the most frequent pair, which will be merged into a new token

The algorithm then creates a new token by concatenating and , adds it to the vocabulary, and replaces all occurrences of the pair in the corpus. This process repeats until the vocabulary reaches the target size.

Why does this work? The greedy nature of BPE means it captures the most common patterns first. Early merges tend to be language-universal patterns (common letter combinations), while later merges capture domain-specific vocabulary. This creates a natural hierarchy: high-frequency subwords get their own tokens, while rare words are decomposed into smaller pieces.

Unigram Language Model

While BPE builds vocabulary through local decisions (always merge the most frequent pair), the unigram approach takes a global perspective. It asks: what vocabulary would make the entire corpus most probable under a simple language model?

The intuition: Think of tokenization as a compression problem. Given limited vocabulary slots, which tokens should we include to most efficiently represent our corpus? Tokens that appear frequently and can't be easily composed from other tokens are the most valuable. The unigram model formalizes this by treating tokenization as probabilistic inference.

Framing tokenization as optimization:

Given a text string , there are many possible ways to segment it into tokens. For example, "learning" could be segmented as:

["learning"](one token)["learn", "ing"](two tokens)["l", "e", "a", "r", "n", "i", "n", "g"](eight characters)

Which segmentation is "best"? The unigram model answers this by assigning probabilities to each possible segmentation and choosing the most probable one.

The core optimization problem is finding the best segmentation for input text :

where:

- : a candidate segmentation consisting of tokens

- : the set of all possible segmentations of text

- : the probability of segmentation under the unigram model

Under the unigram assumption, each token is generated independently. The probability of seeing token doesn't depend on what tokens came before or after it. This simplifying assumption transforms the probability of a segmentation into a product:

where:

- : the probability of token in the learned vocabulary

- : the number of tokens in segmentation

This multiplicative form is what makes the unigram model computationally tractable. Despite the exponentially many possible segmentations, we can use dynamic programming (specifically, the Viterbi algorithm) to find the optimal segmentation in time linear in the text length.

In practice, multiplying many small probabilities leads to numerical underflow. We instead work with log-probabilities, converting the product into a sum: . This is mathematically equivalent but numerically stable.

Training the unigram model:

Unlike BPE which builds up from nothing, the unigram model starts with a large initial vocabulary (all substrings up to some maximum length) and prunes it down using Expectation-Maximization (EM):

- Initialize: Create a vocabulary containing all possible subwords up to a maximum length

- E-step: For each possible segmentation of the corpus, compute how likely it is under current token probabilities. This gives us "expected counts" for each token.

- M-step: Re-estimate token probabilities based on these expected counts:

- Prune: Remove tokens whose deletion would least harm the corpus likelihood

- Repeat steps 2-4 until the vocabulary reaches the desired size

The key insight is that step 4 removes tokens that are "redundant," tokens that can be reconstructed from other tokens without much loss in probability. This naturally preserves the most useful subword units.

Whitespace Handling

SentencePiece's approach to whitespace is straightforward. During training, all whitespace characters are replaced with the special character ▁. This allows the algorithm to learn where word boundaries naturally occur based on the training data.

For example, the sentence "Hello world" becomes "▁Hello▁world" during training. The ▁ prefix indicates word boundaries, and the algorithm can learn that spaces between words are meaningful segmentation points.

A Worked Example

To solidify our understanding, let's trace through exactly how SentencePiece processes a simple sentence: "natural language processing". We'll follow the BPE algorithm step by step, watching how the vocabulary evolves and how tokenization decisions emerge from the learned merge rules.

Step 1: Preprocessing

Before any learning happens, SentencePiece transforms the raw text. Spaces are replaced with the special boundary marker ▁, and a boundary is added at the start to indicate the beginning of a word:

Input: "natural language processing"

Output: "▁natural▁language▁processing"

This preprocessing matters because it allows the algorithm to learn that certain patterns (like "▁the") typically start words, while others (like "ing") typically end them. The ▁ character becomes just another symbol that can participate in merges.

Step 2: Initialize with Characters

The BPE algorithm starts with the finest possible granularity: individual characters. Our initial vocabulary contains every unique character that appears in the preprocessed corpus:

Initial vocabulary: {▁, a, c, d, e, g, i, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, u}

At this point, our text is represented as a sequence of 29 individual tokens:

[▁, n, a, t, u, r, a, l, ▁, l, a, n, g, u, a, g, e, ▁, p, r, o, c, e, s, s, i, n, g]

Step 3: Iterative Merging

Now the algorithm scans the corpus, counting how often each pair of adjacent tokens appears. Suppose the counts look like this (simplified for illustration):

| Pair | Count |

|---|---|

| (a, l) | 3 |

| (a, n) | 2 |

| (n, g) | 2 |

| (i, n) | 1 |

| ... | ... |

The pair (a, l) appears most frequently (in "natural" and "language"), so we merge it:

Merge 1: (a, l) → al

The vocabulary now includes "al" as a single token. Importantly, only adjacent a + l pairs are merged; other instances of "a" and "l" remain separate:

[▁, n, a, t, u, r, al, ▁, l, a, n, g, u, a, g, e, ▁, p, r, o, c, e, s, s, i, n, g]

The algorithm continues, perhaps next merging (a, n) → an, then (n, g) → ng, and so on. After several iterations, we might have:

After 5 merges:

- Vocabulary:

{▁, a, c, d, e, g, i, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, u, al, an, ng, in, ing} - Merge sequence:

[(a,l)→al, (a,n)→an, (n,g)→ng, (i,n)→in, (in,g)→ing]

Notice how "ing" emerges naturally: first "in" is merged, then "in" + "g" becomes "ing". The algorithm discovers morphological patterns without being told about English grammar.

Step 4: Tokenization at Inference Time

Once training is complete, tokenizing new text is straightforward. Given the input "natural language":

-

Preprocess: "natural language" → "▁natural▁language"

-

Start with characters:

[▁, n, a, t, u, r, a, l, ▁, l, a, n, g, u, a, g, e] -

Apply merges in order:

- After

(a,l)→al:[▁, n, a, t, u, r, al, ▁, l, a, n, g, u, a, g, e] - After

(a,n)→an:[▁, n, a, t, u, r, al, ▁, l, an, g, u, a, g, e] - ...and so on until no more merges apply

- After

-

Final tokens: Depending on vocabulary size and training corpus, we might get:

["▁natural", "▁language"]if these full words are in the vocabulary["▁natur", "al", "▁langu", "age"]if the vocabulary is smaller["▁", "n", "a", "t", "u", "r", "a", "l", ▁", "l", ...]if vocabulary is very small

The key insight: the merge order matters. BPE applies merges in exactly the order they were learned during training. This deterministic process ensures that the same text always produces the same tokenization.

Comparing BPE and Unigram Tokenization

For the unigram model, the tokenization process is different. Instead of applying merge rules, we solve an optimization problem. Given "▁natural▁language", we consider all possible segmentations and choose the one with highest probability:

If our vocabulary assigns:

▁natural:▁language:▁nat: ,ural:- ...

The algorithm might find that ["▁natural", "▁language"] gives the highest probability product, making it the optimal segmentation. The Viterbi algorithm efficiently searches through all possibilities without explicitly enumerating them.

Code Implementation

Having walked through the algorithm by hand, let's now implement it in code. Building SentencePiece from scratch will solidify our understanding of each component: the preprocessing that adds word boundaries, the iterative counting and merging that builds the vocabulary, and the deterministic application of merge rules during tokenization.

Defining the SentencePiece Class

Our SimpleSentencePiece class encapsulates the entire BPE pipeline. It maintains two key pieces of state:

vocab: A dictionary mapping each token (string) to its unique ID (integer)merges: An ordered list of merge operations, each recording which pair was merged and what token it produced

The ordering of merges is critical. During tokenization, we must apply them in exactly the same order they were learned:

Let's trace through the key methods:

-

train(): Implements the BPE loop we described earlier. It preprocesses the corpus (adding ▁ boundaries), initializes with character vocabulary, then iteratively finds and merges the most frequent pair until reaching the target vocabulary size. -

tokenize(): Given new text, applies the learned merges in order. This is the deterministic process that ensures consistent tokenization. -

encode(): Converts tokens to their integer IDs, ready for input to a neural network.

Training on a Sample Corpus

Now let's see the algorithm in action. We'll train on a small NLP-themed corpus and observe what patterns it discovers:

The output reveals the compression at work. We started with individual characters and, through iterative merging, built up a vocabulary of subword units. The number of tokens needed to represent "natural language" is now much smaller than the character count. This compression is what makes subword tokenization efficient.

Examining Learned Merges

The merge sequence tells us exactly what patterns the algorithm discovered in the training corpus. Early merges capture the most frequent character pairs, the "building blocks" that appear across many words:

Notice the progression: early merges are simple character pairs, while later merges combine previously-merged tokens into increasingly complex units. This hierarchical structure mirrors the morphological patterns in language. Common suffixes like "ing" or "tion" emerge naturally from the statistics, even though the algorithm knows nothing about linguistics.

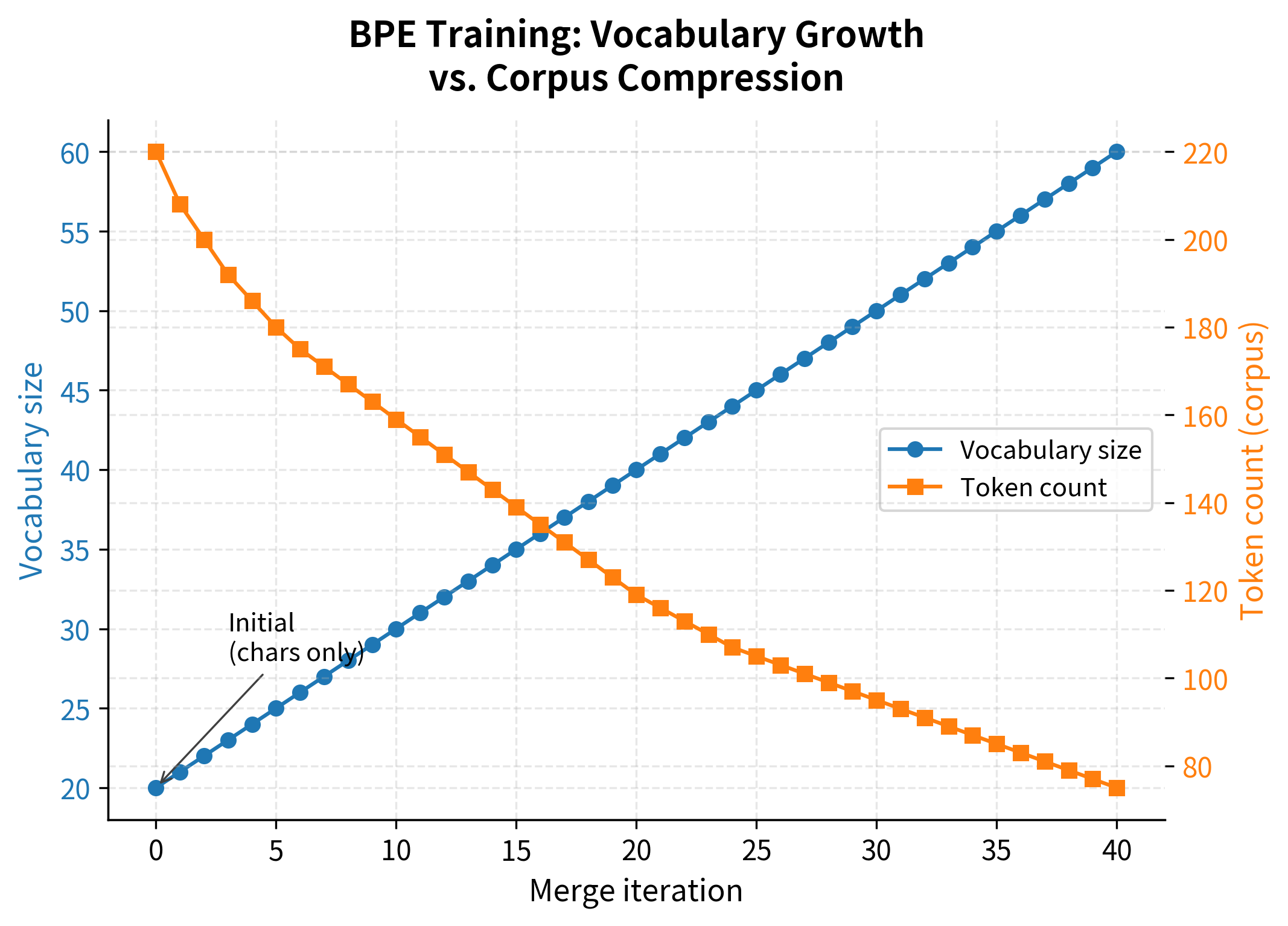

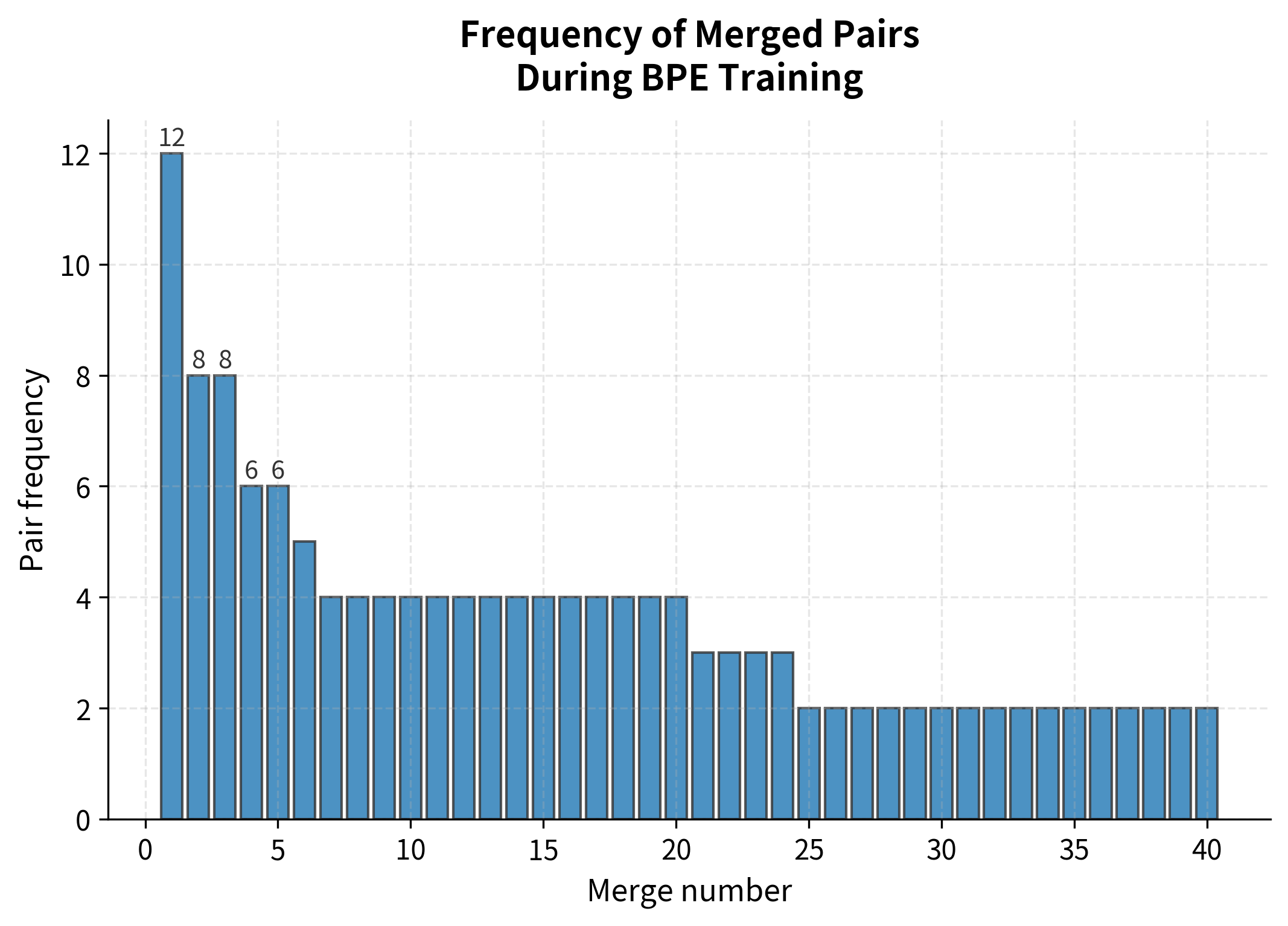

Visualizing the BPE Training Process

To better understand how BPE builds its vocabulary, let's visualize the training dynamics. We'll track how the vocabulary grows and how the corpus representation becomes more compressed with each merge operation:

The visualization reveals the fundamental trade-off in BPE training: each merge adds one token to the vocabulary while reducing the number of tokens needed to represent the corpus. Early merges achieve the greatest compression gains because they target the most frequent pairs.

The frequency distribution confirms the greedy selection pattern: the first merge captures a pair appearing many times, while later merges address progressively rarer combinations. This explains why BPE tends to create short, frequent tokens early and longer, domain-specific tokens later.

Tokenizing Unseen Text

The true test of any tokenization algorithm is how it handles text it hasn't seen before. Unlike word-level tokenizers that map unknown words to a single <UNK> token, subword tokenizers gracefully decompose novel words into known pieces:

Even though "deep processing" as a complete phrase never appeared in training, the model handles it gracefully. It recognizes subword patterns it learned from related words, perhaps "process" from "processing" and "deep" from other contexts. The compression ratio quantifies this efficiency: a ratio of 2x means we need half as many tokens as characters, 3x means one-third, and so on.

This robustness to unseen text is why subword tokenization has become the standard in modern NLP. Rare words, technical terms, and even typos can be decomposed into known subwords, allowing models to make reasonable predictions about their meaning.

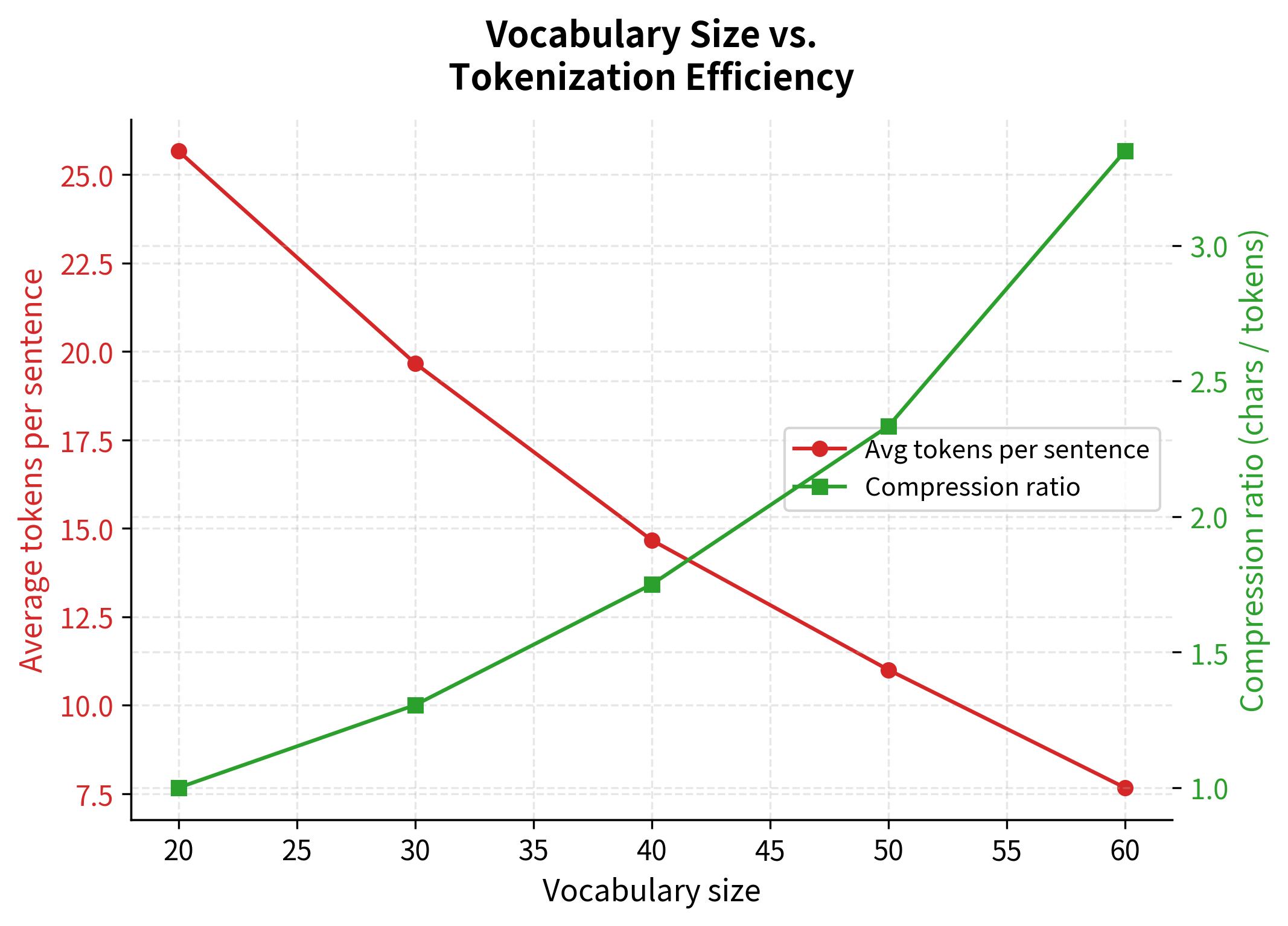

The Effect of Vocabulary Size

How does vocabulary size affect tokenization? Let's train multiple models with different vocabulary sizes and compare how they tokenize the same text:

The plot reveals the diminishing returns of larger vocabularies. Early vocabulary additions (the first 20-30 tokens beyond characters) provide substantial compression improvements. However, as vocabulary size grows further, each additional token contributes less to overall efficiency. This trade-off motivates the choice of vocabulary sizes in practice. Models like BERT use ~30,000 tokens, balancing compression against embedding table size.

Production Usage

SentencePiece is widely used in production systems. Let's see how to use the official implementation:

The official implementation handles edge cases like rare Unicode characters, provides both BPE and unigram modes, and supports multilingual text out of the box.

Key Parameters

When working with SentencePiece, several parameters critically affect tokenization quality and model performance:

-

vocab_size (): Controls the final vocabulary size. Larger vocabularies (8,000-32,000) capture more subword patterns but increase computational cost. Smaller vocabularies (1,000-4,000) are more efficient but may lose rare patterns. The vocabulary size directly affects the average number of tokens per word; larger vocabularies tend to produce fewer, longer tokens.

-

model_type: Choose between

'bpe'for compression-focused tokenization and'unigram'for language modeling approaches. BPE greedily merges the most frequent pairs at each step, while unigram optimizes the global probability across all possible segmentations. BPE is generally faster to train while unigram often produces better token boundaries for downstream tasks. -

character_coverage (): Set to for multilingual support to ensure all Unicode characters are covered. Lower values (e.g., ) can be used for language-specific models, allowing the algorithm to treat the rarest 0.5% of characters as unknown tokens to reduce vocabulary size.

-

byte_fallback: Enables handling of rare or unseen characters by falling back to byte-level representation. When a character isn't in the vocabulary, it's encoded as its raw UTF-8 bytes (each prefixed with a special marker). Essential for robust multilingual tokenization.

Limitations & Impact

SentencePiece's byte-level approach changed how tokenization works, but it comes with trade-offs. The lack of explicit whitespace handling can make debugging difficult, and the learned token boundaries may not always align with linguistic intuition. However, these limitations are outweighed by the algorithm's ability to handle any language without preprocessing.

SentencePiece enabled the development of truly multilingual models like mBERT and XLM-R, which can process hundreds of languages with a single vocabulary. This made language models more accessible across different linguistic communities.

Summary

SentencePiece introduced a data-driven approach to tokenization that treats text as raw bytes and learns optimal subword units directly from corpora. By eliminating language-specific preprocessing and handling whitespace through special prefixes, it enables truly multilingual tokenization.

The algorithm's two main variants offer different trade-offs:

- BPE greedily merges the most frequent adjacent pair at each step:

- Unigram finds the segmentation that maximizes total probability:

While the approach can produce counterintuitive tokenizations, it enables truly multilingual NLP. Many of today's most capable language models use SentencePiece, including T5, ALBERT, and XLM-RoBERTa.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about SentencePiece tokenization.

Comments