Explore tokenization challenges in NLP including number fragmentation, code tokenization, multilingual bias, emoji complexity, and adversarial attacks. Learn quality metrics.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Tokenization Challenges

You've now learned the major subword tokenization algorithms: BPE, WordPiece, Unigram, and SentencePiece. These techniques have transformed NLP by elegantly solving the vocabulary problem. But tokenization isn't a solved problem. Edge cases lurk everywhere, from numbers that fragment unpredictably to emoji sequences that explode into dozens of tokens.

This chapter examines the practical challenges that arise when tokenizers meet real-world text. We'll explore why "1000" and "1,000" produce different token sequences, how code tokenization creates surprising failure modes, and why multilingual models struggle with fair representation across languages. You'll learn to recognize tokenization artifacts, understand adversarial attacks that exploit tokenizer weaknesses, and measure tokenization quality systematically.

These aren't academic curiosities. When your model fails to count to ten correctly, produces garbled output for certain inputs, or shows unexpected biases across languages, tokenization is often the culprit. Understanding these challenges helps you debug mysterious model behaviors and choose appropriate tokenizers for your applications.

Number Tokenization

Numbers present one of the most frustrating challenges for subword tokenizers. Unlike words, which have stable morphological structure, numbers can appear in countless formats: "42", "42.0", "42,000", "4.2e4", "0x2A". Each format fragments differently during tokenization, creating inconsistent representations that downstream models struggle to interpret.

The Fragmentation Problem

Most tokenizers learn their vocabularies from text corpora where numbers appear less frequently than words. As a result, numbers often get split into seemingly arbitrary chunks. The number "1234567" might become ['12', '34', '567'] or ['1', '234', '567'] depending on what patterns the tokenizer happened to see during training.

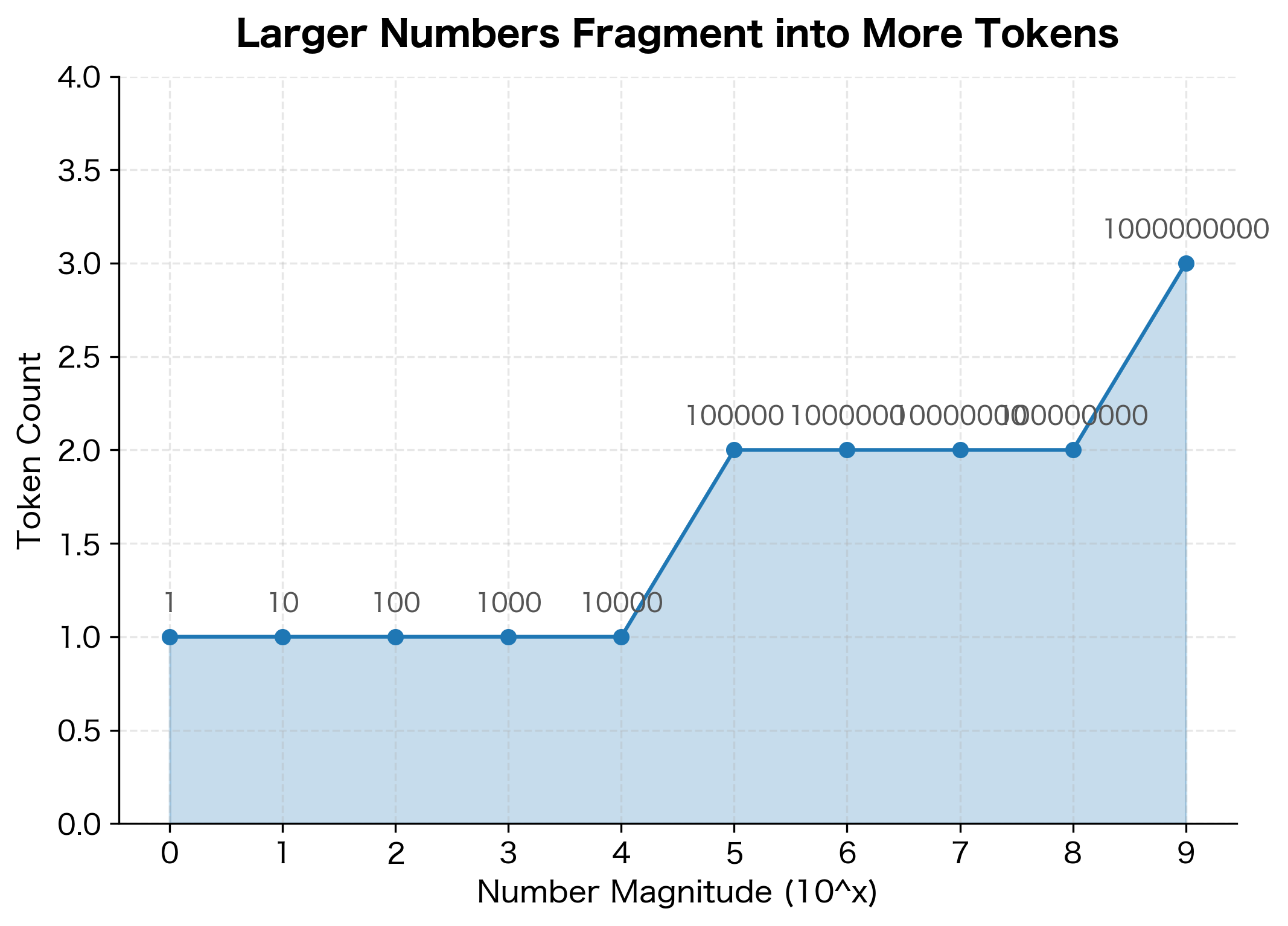

The results reveal several concerning patterns. Small numbers like "42" and "100" tokenize efficiently as single tokens because they appear frequently in training data. But larger numbers fragment unpredictably: "1000" might be two tokens while "10000" becomes three. Decimal numbers split at the decimal point, and scientific notation produces even more fragments.

Why Number Fragmentation Matters

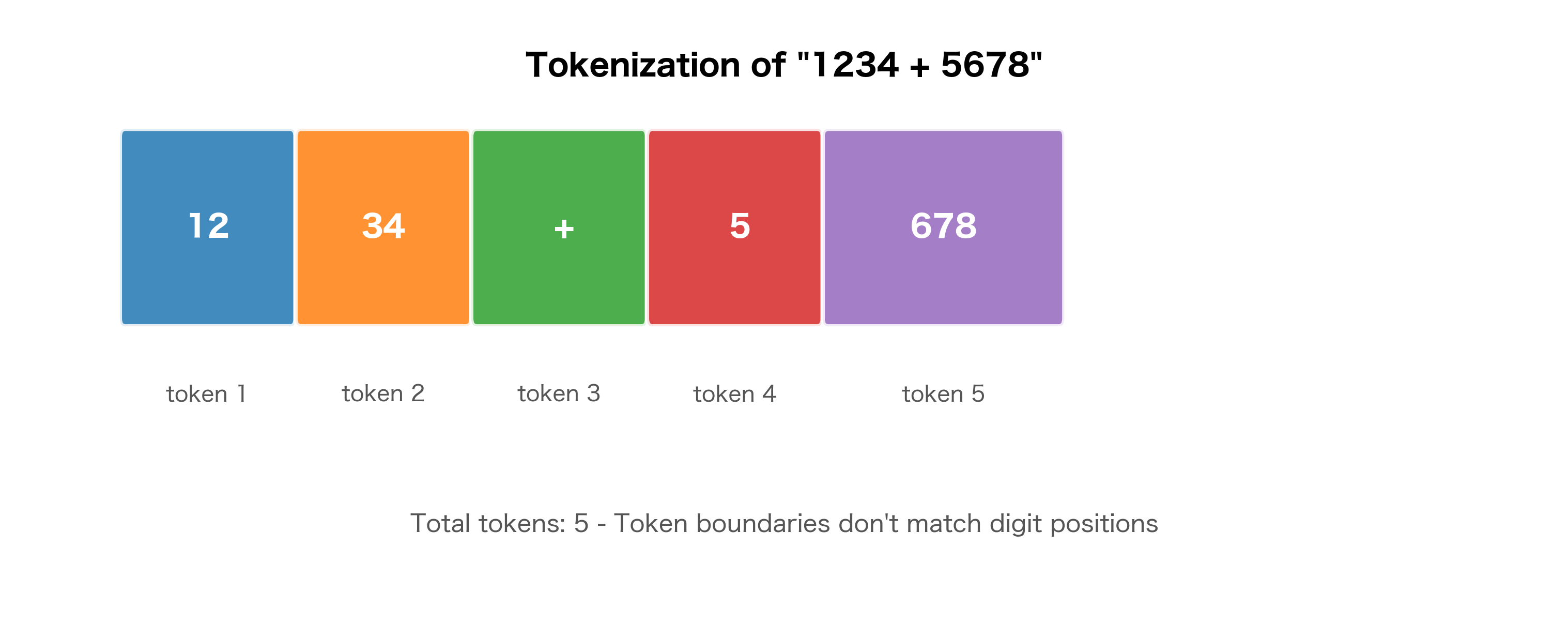

This fragmentation creates real problems for language models. Consider arithmetic: to compute "1234 + 5678", the model must somehow understand that ['12', '34'] represents twelve hundred thirty-four, not the numbers twelve and thirty-four. The model has no explicit representation of place value, so it must learn these relationships from context.

The relationship between number magnitude and token count is roughly logarithmic, but with steps rather than a smooth curve. This reflects the tokenizer's vocabulary: it learned tokens for common number patterns (like "000" or "100") but must decompose less common combinations character by character.

Format Sensitivity

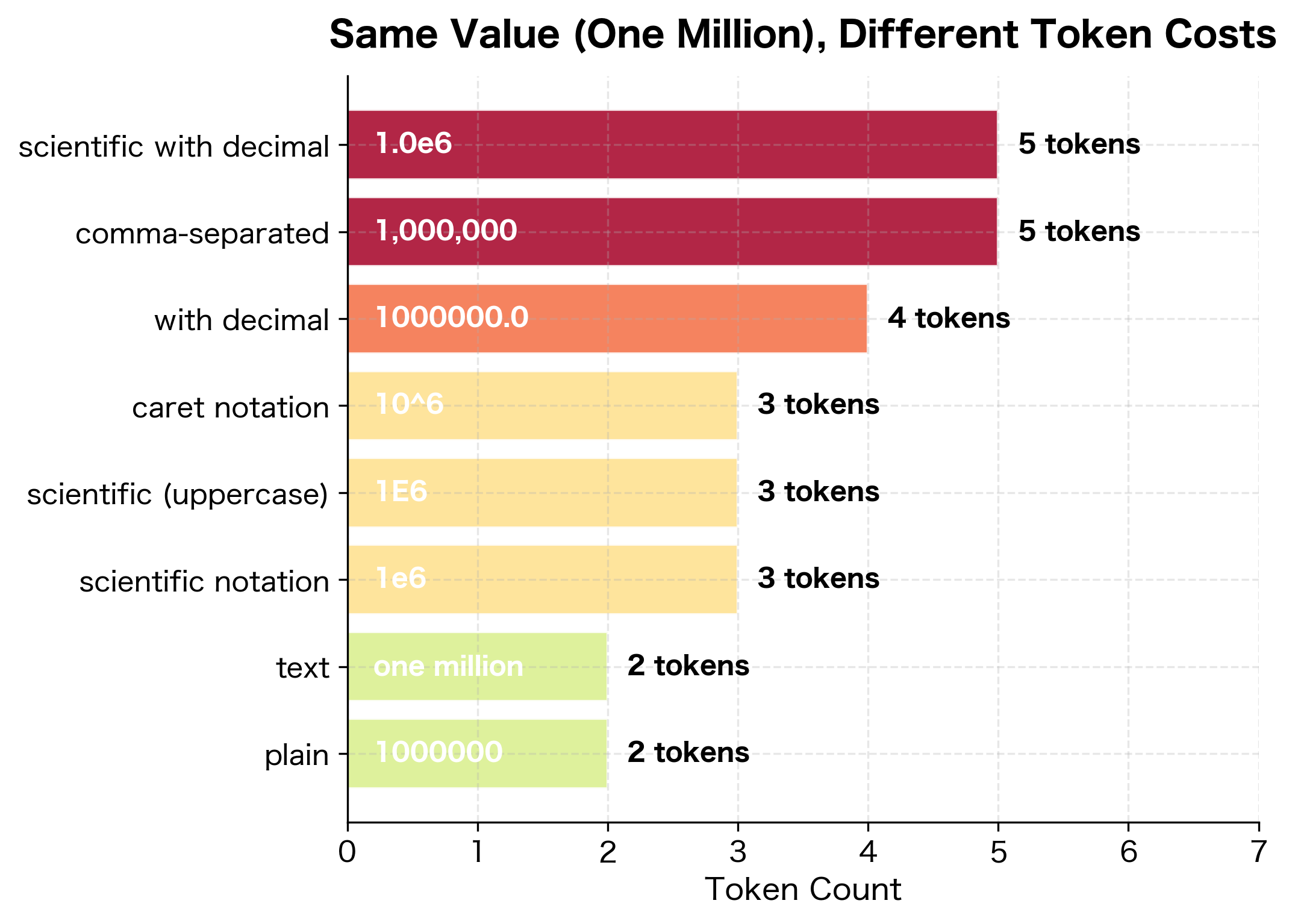

The same numeric value can produce wildly different tokenizations depending on its format. This creates unexpected inconsistencies in how models process equivalent quantities.

The table reveals dramatic variation. "1000000" as a plain number might tokenize into three or four pieces, while "1,000,000" with commas adds tokens for each separator. Scientific notation "1e6" is often more compact but less common in training data. The text representation "one million" uses two intuitive tokens but looks nothing like the numeric forms.

This format sensitivity has practical implications. A model trained primarily on comma-separated numbers might struggle with scientific notation, and vice versa. Financial applications often encounter mixed formats, which models process inconsistently.

Arithmetic Challenges

Number tokenization directly impacts arithmetic performance. When numbers fragment into tokens that don't align with place value, models must learn implicit arithmetic patterns that humans take for granted.

Simple expressions like "5 + 3 = 8" tokenize cleanly, with each number as a single token. But multi-digit arithmetic creates alignment problems: "1234" becomes multiple tokens with different boundaries than "5678", yet the model must learn that carrying happens across these arbitrary splits.

Code Tokenization

Programming languages present unique tokenization challenges. Code mixes natural language elements (variable names, comments) with syntactic structures (operators, brackets, indentation) in ways that confuse tokenizers trained primarily on prose.

Identifier Fragmentation

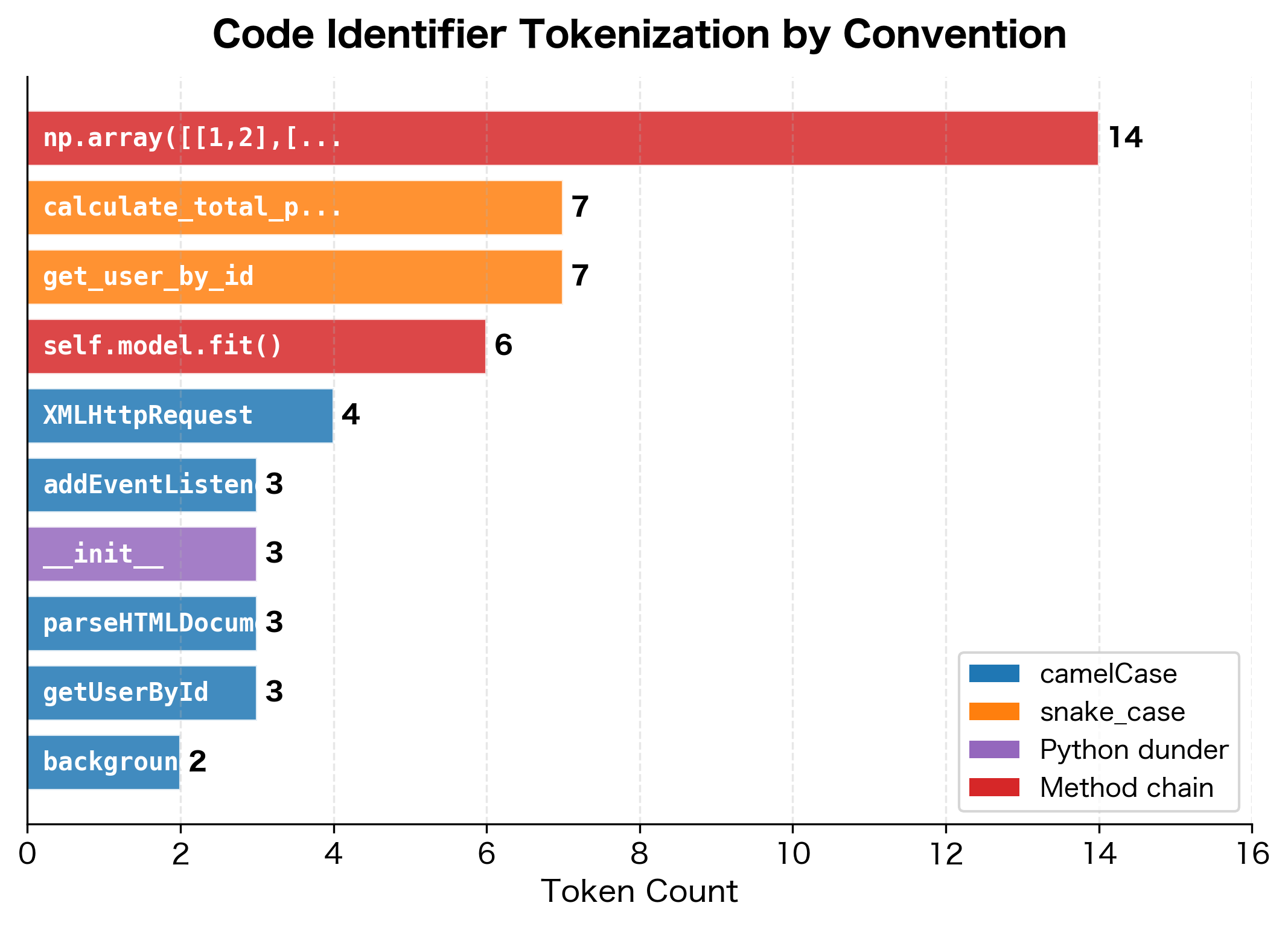

Variable and function names in code often use conventions like camelCase or snake_case that pack multiple words into single identifiers. Tokenizers must decide whether to split these at boundaries or treat them as atomic units.

The tokenization reveals inconsistent handling of coding conventions. CamelCase names like "getUserById" might split at capital letters, but not consistently. For example, "XMLHttpRequest" handles the acronym differently. Snake_case names split at underscores since they're treated as separate tokens. Special Python identifiers like __init__ produce surprising fragments.

Operator and Syntax Tokenization

Programming operators and syntactic elements often tokenize inefficiently because they appear infrequently in natural language training data.

Multi-character operators like "==" or "!=" sometimes tokenize as single units if they appeared frequently in the training data, but more exotic operators like "<<<" (shell redirect) or "::" (C++ scope resolution) fragment into their component characters. Python decorators and keywords may or may not be recognized depending on the tokenizer's training corpus.

Whitespace and Indentation

Python and other whitespace-sensitive languages pose a particular challenge. Indentation carries semantic meaning, but tokenizers often collapse or normalize whitespace.

The tokenization preserves newlines and some indentation, but the representation is verbose. Each line of code produces many tokens, and the model must learn that four-space indentation has different meaning than two-space. This creates a semantic gap between how programmers think about code structure and how models process it.

The same simple add function produces different token counts depending on the language syntax:

addfunctions across programming languages. Python's terseness and minimal syntax yield the highest efficiency, while Rust's type annotations and C's verbosity produce more tokens.| Language | Tokens | Characters | Chars/Token |

|---|---|---|---|

| Python | 11 | 30 | 2.7 |

| JavaScript | 18 | 42 | 2.3 |

| C | 21 | 44 | 2.1 |

| Rust | 22 | 40 | 1.8 |

Python's minimal syntax produces the fewest tokens, achieving 2.7 characters per token. Rust's explicit type annotations (i32) and return type syntax add overhead, dropping efficiency to 1.8 characters per token. This efficiency gap matters when processing large codebases: a Python project may fit 50% more code into the same context window compared to Rust.

Multilingual Challenges

Tokenizers trained primarily on English text struggle with other languages, creating systematic biases that affect model performance and fairness across linguistic communities.

Script and Language Coverage

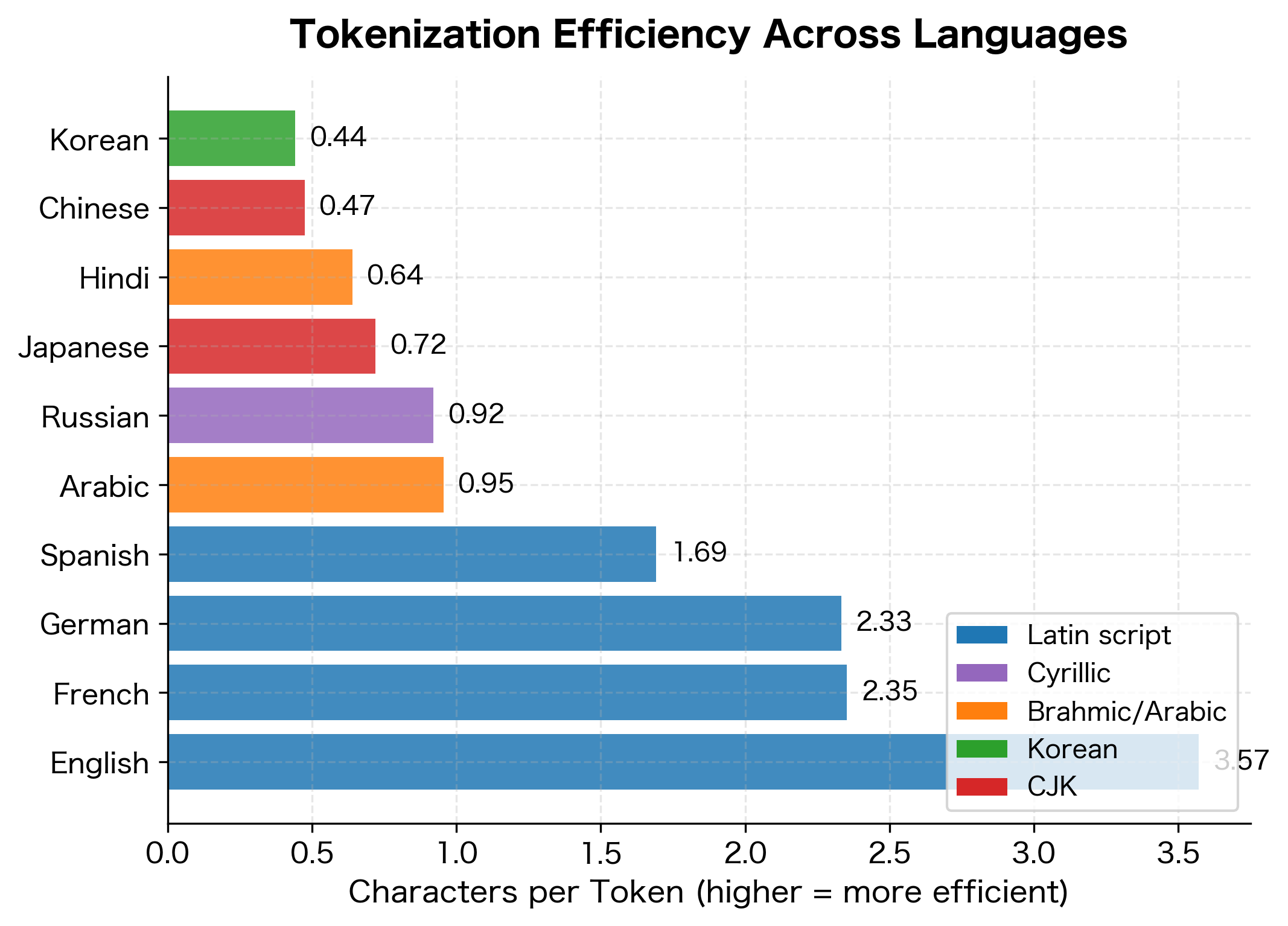

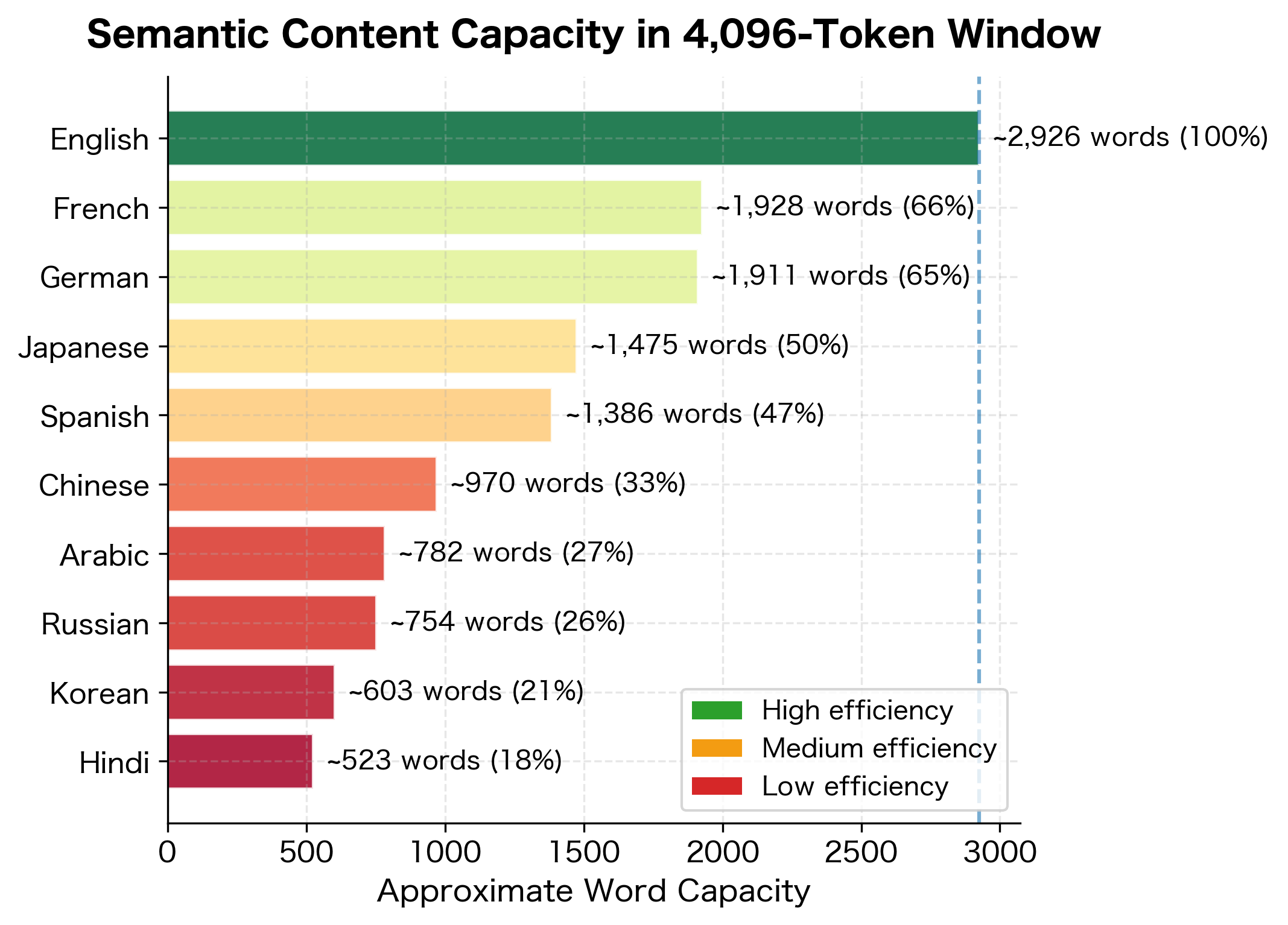

Different writing systems require dramatically different tokenization strategies. Alphabetic languages like English segment into words at whitespace, but Chinese, Japanese, and Thai have no word boundaries. Arabic and Hebrew write right-to-left. Devanagari and other Brahmic scripts combine consonants and vowels into complex glyphs.

The table reveals striking disparities. English achieves high efficiency with around 4-5 characters per token, while Chinese and Japanese fragment into many more tokens for equivalent semantic content. This isn't just an efficiency problem: models have a fixed context window measured in tokens, so Chinese text effectively gets less context than English text of similar length.

The Cost of Multilingual Text

The efficiency disparity has concrete costs. When you're paying per token for API access or working with limited context windows, users of lower-efficiency languages effectively pay more or get less context.

Code-Switching and Mixed Language

Real-world text often mixes languages, creating additional challenges for tokenizers trained on monolingual corpora.

When languages mix within a sentence, the tokenizer must handle sudden script changes. The non-English portions typically fragment more heavily than if they appeared in monolingual text, because the surrounding English context doesn't provide helpful merge patterns.

Emoji and Unicode Edge Cases

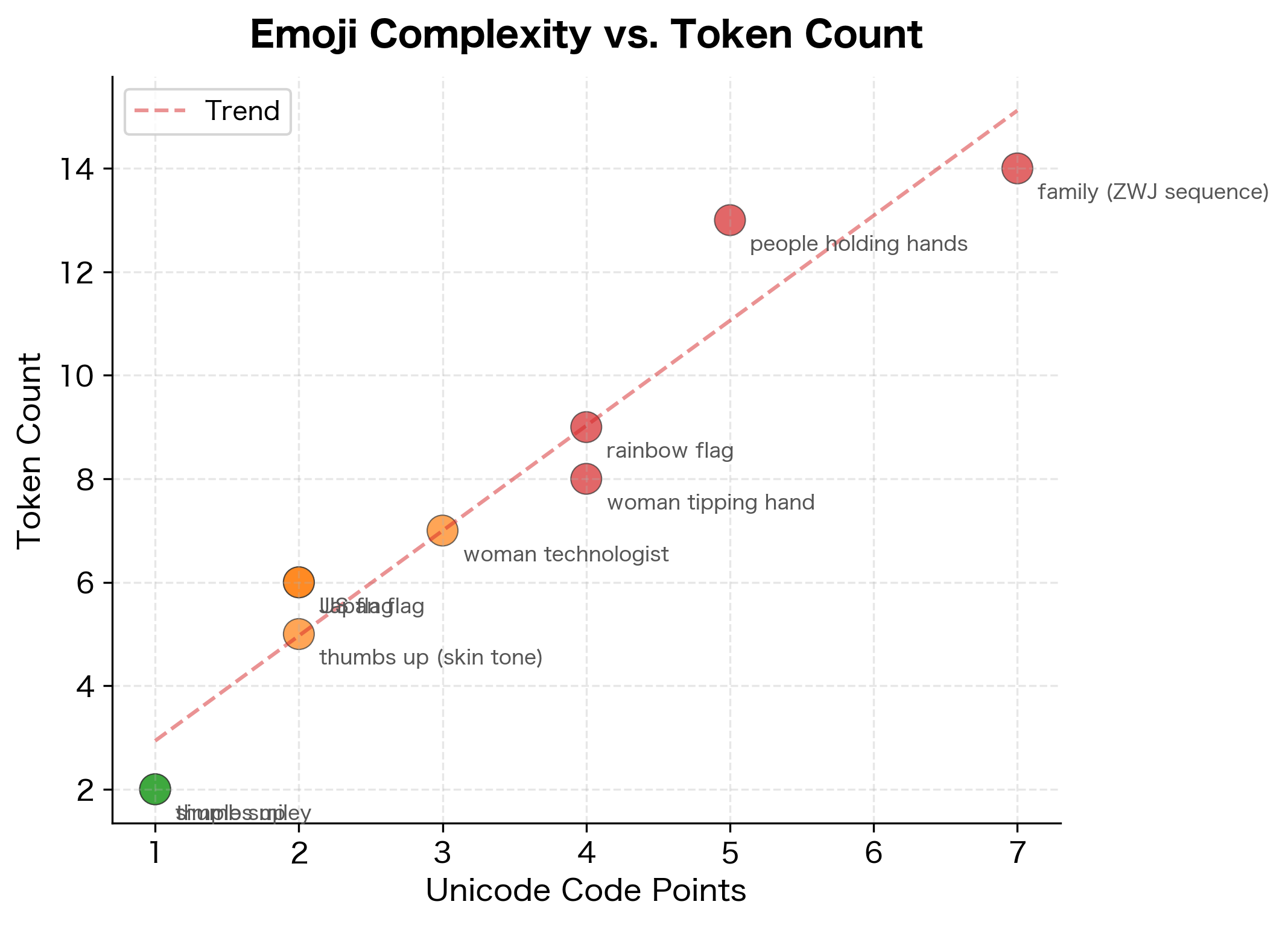

Emoji and special Unicode characters reveal the limits of byte-based tokenization. What appears as a single character on screen might be multiple Unicode code points, each encoded as multiple bytes.

Emoji Tokenization

Modern emoji can be surprisingly complex. A simple smiley face is one code point, but emoji with skin tone modifiers, gender variations, or family compositions are sequences of multiple code points joined by Zero Width Joiners (ZWJ).

A simple smiley might be 1-2 tokens, but a family emoji with multiple people can explode into a dozen or more tokens. Each skin tone modifier, gender indicator, and ZWJ character adds to the byte count and thus the token count.

Unicode Normalization Issues

Unicode allows multiple ways to represent the same visual character. The letter "é" can be a single code point (U+00E9, "Latin Small Letter E with Acute") or two code points (U+0065 "Latin Small Letter E" + U+0301 "Combining Acute Accent"). These normalize to the same visual appearance but may tokenize differently.

Special Characters and Symbols

Mathematical symbols, currency signs, and other special characters may or may not be in the tokenizer's vocabulary.

Mathematical symbols like π and ∑ may fragment into byte sequences that models must learn to interpret. Greek letters used in scientific text face similar challenges. This creates a disparity between prose and technical writing that affects how well models handle STEM content.

Tokenization Artifacts

Tokenization creates artifacts: patterns in the token sequence that don't reflect linguistic structure but arise from the tokenizer's learned merge rules. These artifacts can cause unexpected model behaviors.

Position-Dependent Tokenization

The same substring may tokenize differently depending on its position in a word. This happens because BPE learns different merge rules for word-initial, word-internal, and word-final positions.

Notice how "low" tokenizes differently as a standalone word versus when embedded in "fellow" or "allow". The leading space marker (Ġ in GPT-2) affects which merge rules apply. This position sensitivity means morphologically related words may have different token representations.

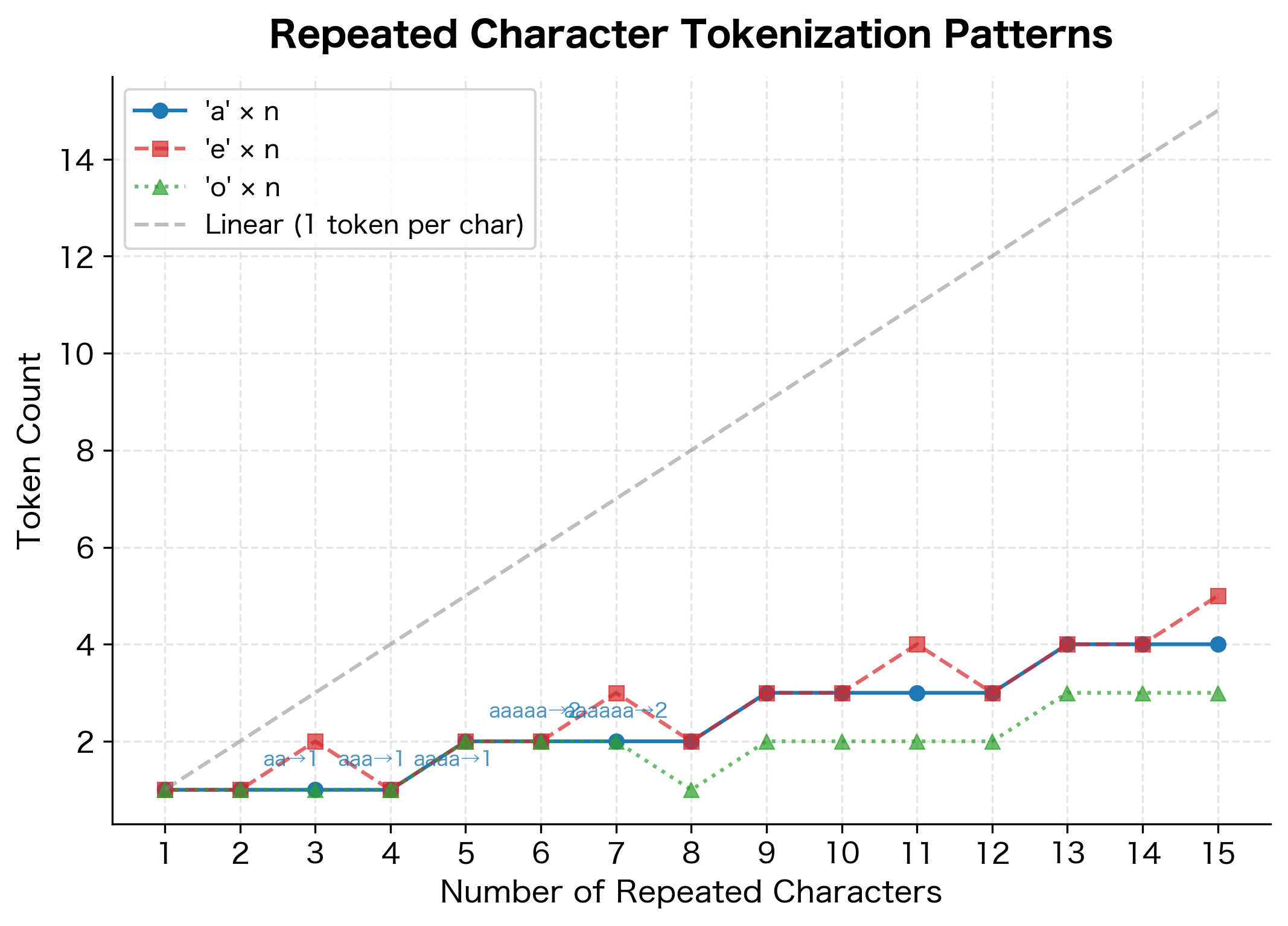

Repeated Character Anomalies

Long sequences of repeated characters create unusual tokenization patterns. The tokenizer may have learned specific tokens for common repeats (like "ee" in "feet") but must fall back to character-by-character tokenization for longer sequences.

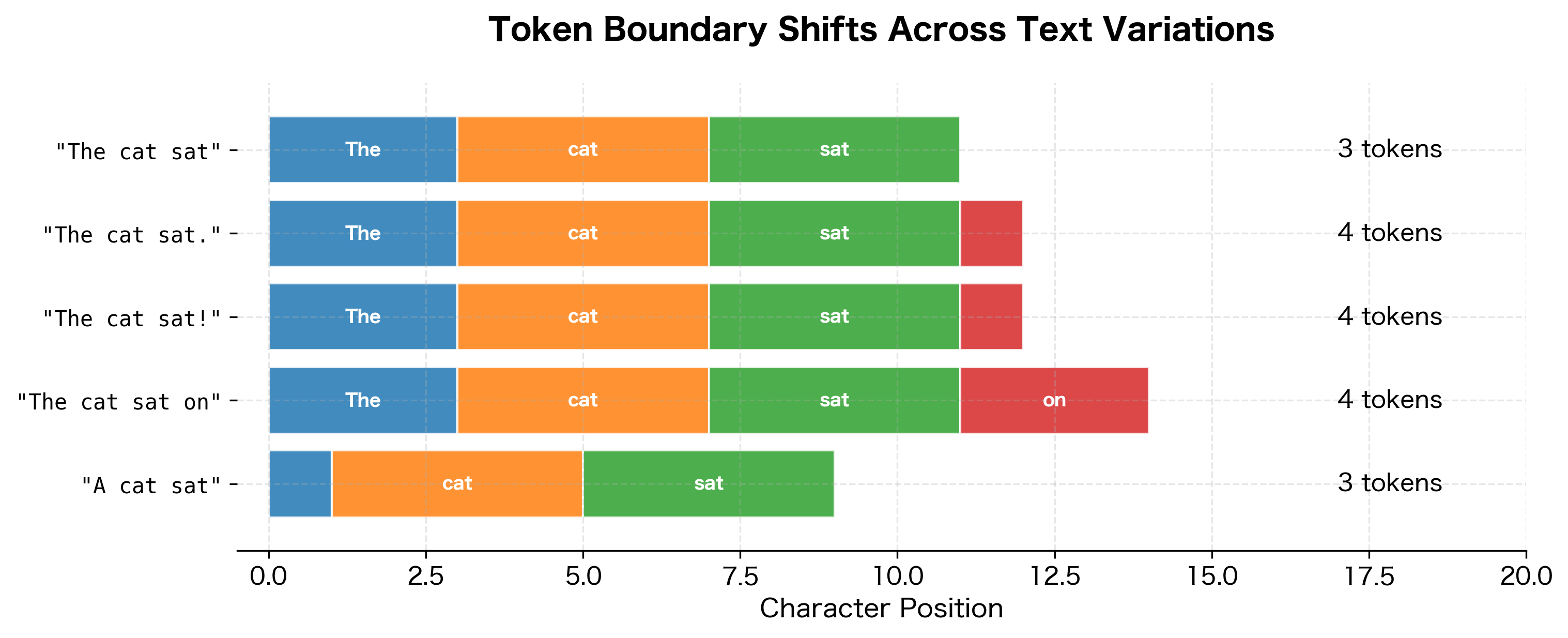

Tokenization Boundary Effects

Slight changes in input text can cause cascading changes in tokenization. Adding or removing a single character might shift token boundaries throughout the sequence.

Notice how adding a single punctuation mark can change the token count. More significantly, changing a word can affect the tokenization of adjacent words if it shifts the byte alignment of subsequent text.

Adversarial Tokenization

Malicious actors can exploit tokenization quirks to confuse language models or bypass content filters. Understanding these attacks helps build more robust systems.

Token Boundary Manipulation

By carefully crafting input text, attackers can create token boundaries that obscure the true meaning of the input. This technique can evade content moderation systems that operate on token-level patterns.

Prompt Injection via Tokenization

Attackers can insert invisible characters or use Unicode lookalikes to inject instructions that appear innocuous to human reviewers but get processed differently by models.

An attack where malicious instructions are embedded in user input, designed to override the system's intended behavior. Tokenization artifacts can make these injections harder to detect because the malicious content may not match expected token patterns.

| Word | Script | Tokens | Token Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| admin | Latin script | 1 | ['admin'] |

| аdmin | Cyrillic 'а' | 5 | ['Ð', '°', 'dm', 'in'] |

| αdmin | Greek 'α' | 5 | ['α', 'dm', 'in'] |

This attack vector is particularly dangerous for content moderation. A filter searching for the token ['admin'] will miss both homoglyph variants entirely, since they produce completely different token sequences. Robust detection requires Unicode normalization and script analysis before tokenization.

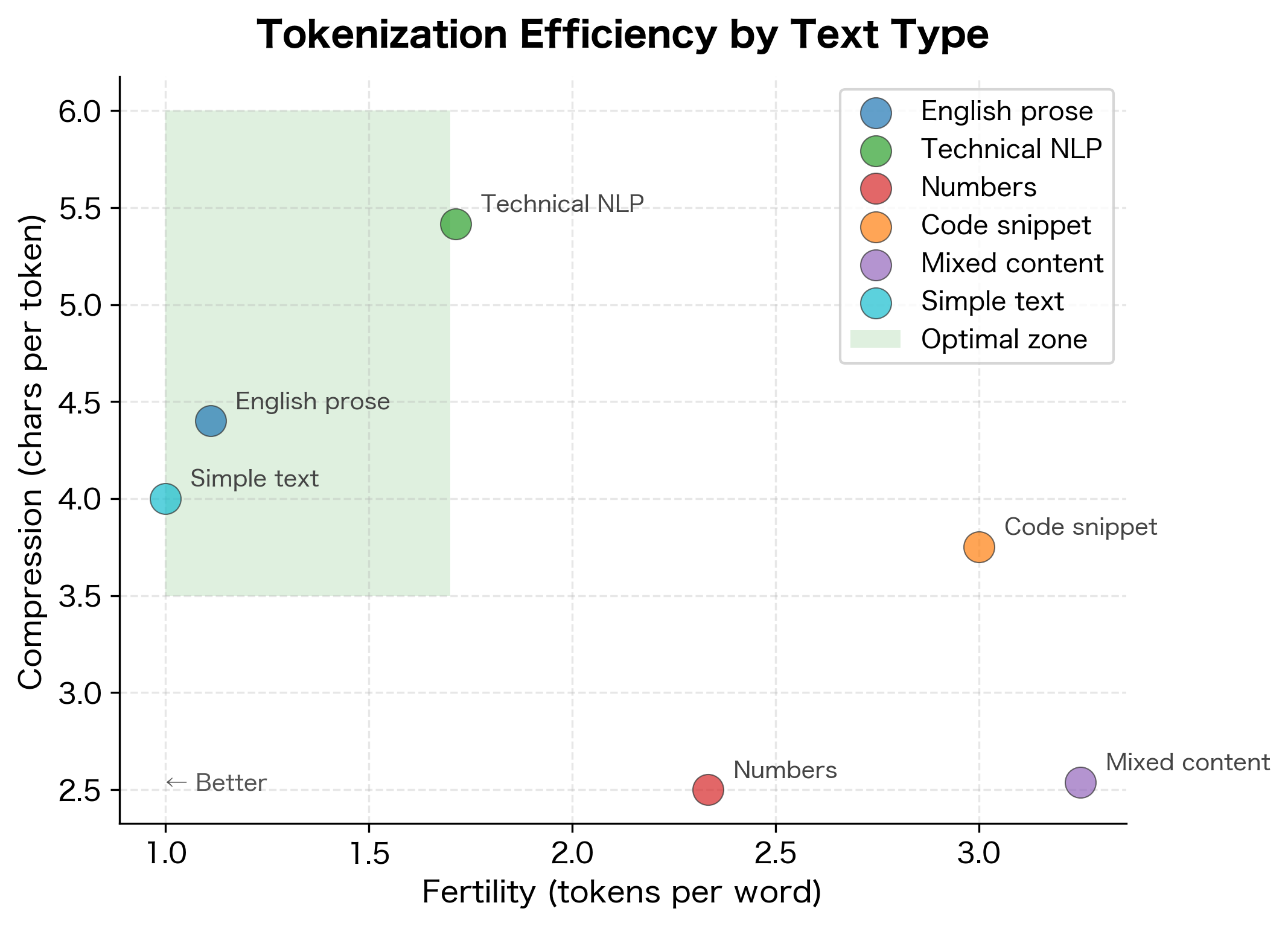

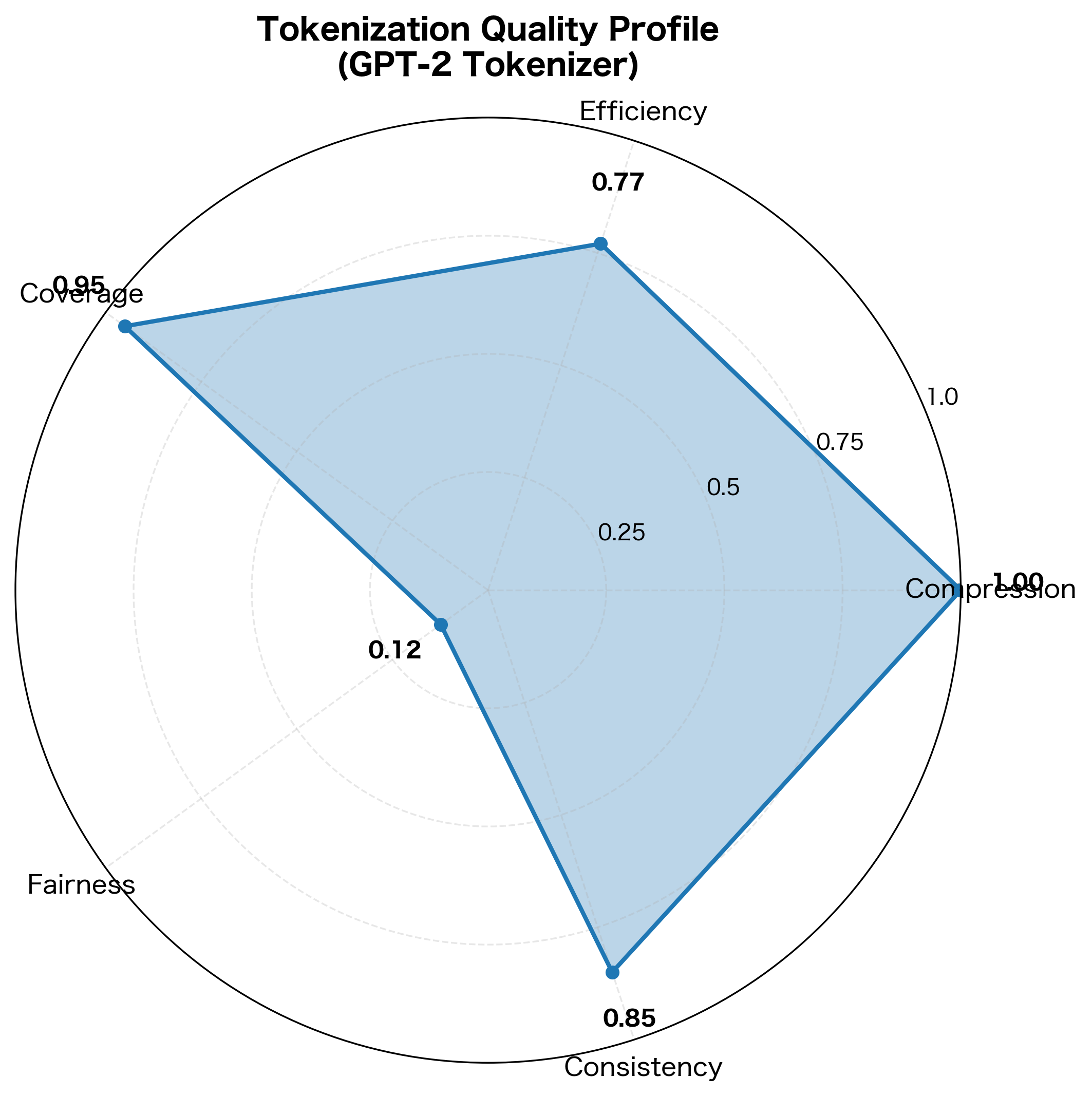

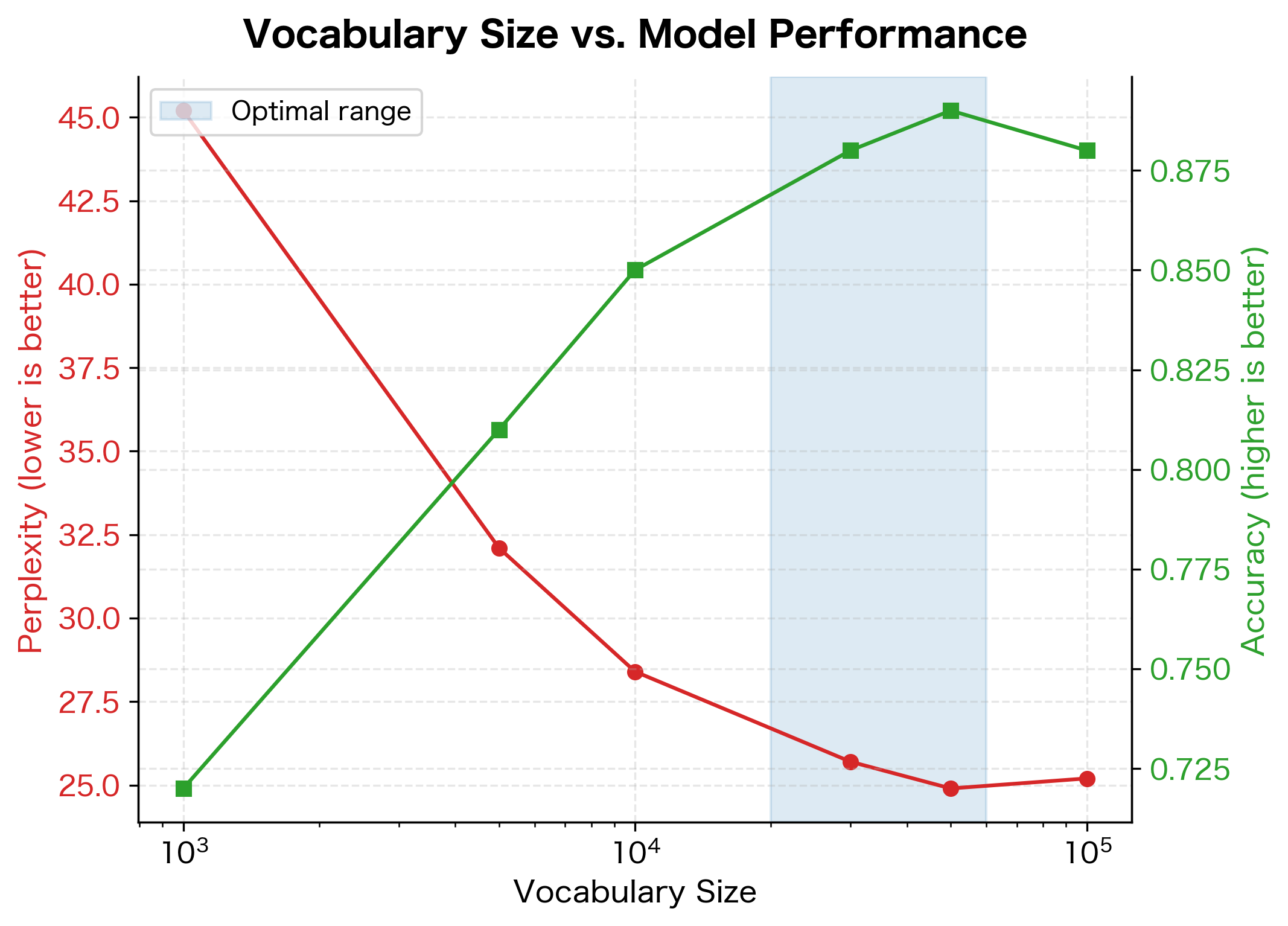

Measuring Tokenization Quality

How do we evaluate whether one tokenizer is better than another? Several metrics help quantify tokenization quality across different dimensions.

Compression Metrics

The primary goal of subword tokenization is compression: representing text with fewer tokens than characters. Compression ratio and fertility measure this directly.

The average number of tokens produced per word. Lower fertility indicates more efficient tokenization, meaning common words are represented by single tokens rather than being split into subwords.

A compression ratio around 4-5 characters per token is typical for English text with a well-trained tokenizer. Fertility around 1.2-1.5 tokens per word indicates that most words are either single tokens or split into just two pieces.

Cross-Language Fairness

For multilingual applications, tokenization efficiency should be roughly equal across languages. Large disparities indicate unfair representation.

A disparity ratio close to 1.0 indicates fair representation across languages. Ratios above 2.0 suggest significant bias toward some languages. The standard deviation captures how much variation exists in tokenization efficiency.

Downstream Task Correlation

Ultimately, tokenization quality matters because it affects downstream task performance. Better tokenization generally correlates with better model performance, but the relationship isn't always straightforward.

Best Practices and Recommendations

Based on these challenges, several best practices emerge for working with tokenizers effectively.

Choosing the Right Tokenizer

The optimal tokenizer depends on your application:

- English-only applications: GPT-2/GPT-4 tokenizers work well, offering good compression and vocabulary coverage

- Multilingual applications: Consider tokenizers trained on balanced multilingual corpora, like those from mT5 or XLM-RoBERTa

- Code-heavy applications: Look for tokenizers explicitly trained on code, like CodeBERT or StarCoder tokenizers

- Domain-specific: Consider training a custom tokenizer on domain text if standard tokenizers perform poorly

Preprocessing for Better Tokenization

Some preprocessing steps can improve tokenization consistency:

Monitoring Tokenization in Production

Track tokenization metrics to catch issues early:

- Token count per request: Sudden increases may indicate adversarial input or unusual content

- OOV rates: If you're using an older tokenizer, track how often byte-fallback occurs

- Language distribution: Monitor whether tokenization efficiency varies across user populations

- Cost per character: Track effective costs across different content types

Summary

Tokenization challenges arise at the intersection of linguistic diversity and computational constraints. We've explored several key problem areas:

Number tokenization fragments inconsistently based on magnitude and format, creating challenges for arithmetic and numerical reasoning. The same value tokenizes differently depending on whether it's written as "1000", "1,000", or "1e3".

Code tokenization struggles with programming conventions like camelCase and snake_case, creating verbose representations of identifiers and operators. Whitespace-sensitive languages pose particular challenges.

Multilingual text reveals systematic biases in tokenizers trained primarily on English. Scripts like Chinese and Japanese fragment into many more tokens for equivalent semantic content, creating unfair representation in fixed-context models.

Emoji and Unicode expose the complexity beneath seemingly simple characters. Compound emoji can explode into dozens of tokens, and Unicode normalization affects tokenization consistency.

Tokenization artifacts cause unexpected model behaviors when slight input changes cascade into different token boundaries. Position-dependent tokenization means the same substring represents differently in different contexts.

Adversarial attacks exploit these quirks to bypass content filters and inject malicious prompts. Homoglyphs and invisible characters can obscure true content while appearing innocuous to human reviewers.

Quality metrics help evaluate and compare tokenizers: compression ratio, fertility, cross-language fairness, and correlation with downstream performance all provide useful signals.

Understanding these challenges helps you debug mysterious model behaviors, choose appropriate tokenizers for your applications, and build more robust NLP systems. Tokenization may seem like a solved problem, but as we've seen, edge cases lurk everywhere, and careful attention to tokenization quality can significantly impact model performance.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about tokenization challenges in NLP.

Comments