Master Conditional Random Field training with the forward-backward algorithm, gradient computation, and L-BFGS optimization for sequence labeling tasks.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

CRF Training

Conditional Random Fields are powerful models for sequence labeling, but their power comes with computational challenges. Unlike simple classifiers that make independent predictions for each token, CRFs model dependencies between labels across the entire sequence. Training a CRF means finding weights that maximize the probability of correct label sequences given their input features, while accounting for all possible alternative labelings.

This chapter explores how to train CRFs effectively. You'll learn the mathematical foundation of the log-likelihood objective, understand why the forward-backward algorithm is essential for efficient gradient computation, see how modern optimizers like L-BFGS converge faster than simple gradient descent, and discover how feature templates and regularization shape what a CRF can learn. By the end, you'll be able to train CRFs on real sequence labeling tasks and understand what's happening under the hood.

The Log-Likelihood Objective

Training a CRF means finding feature weights that make correct label sequences probable. Given training data consisting of observation sequences and their correct label sequences , we want to maximize the conditional probability of seeing these correct labels.

The log-likelihood is the sum of log probabilities of the correct label sequences across all training examples. Taking the log transforms products into sums and makes optimization numerically stable.

For a single training example with observation sequence and label sequence , the CRF defines the conditional probability as:

where:

- : the label sequence of length

- : the observation sequence (features at each position)

- : the -th feature function, which examines the previous label , current label , the full observation sequence , and position

- : the weight for feature (what we're learning)

- : the partition function, which sums over all possible label sequences to normalize probabilities

The partition function deserves special attention:

where:

- : ranges over all possible label sequences

- The sum includes sequences, where is the number of possible labels

This summation over exponentially many sequences is what makes CRF training computationally interesting. With 9 labels and 20 tokens, we'd have possible sequences. Enumerating them directly is impossible.

The Objective Function

Taking the log of the conditional probability gives us the log-likelihood for a single example:

The first term is the "score" of the correct sequence, which is easy to compute. The second term, , requires summing over all possible sequences, which is the computational bottleneck.

For the full training set with examples, we sum the log-likelihoods:

where:

- : the total log-likelihood as a function of all weights

- : the vector of all feature weights

Our goal is to find .

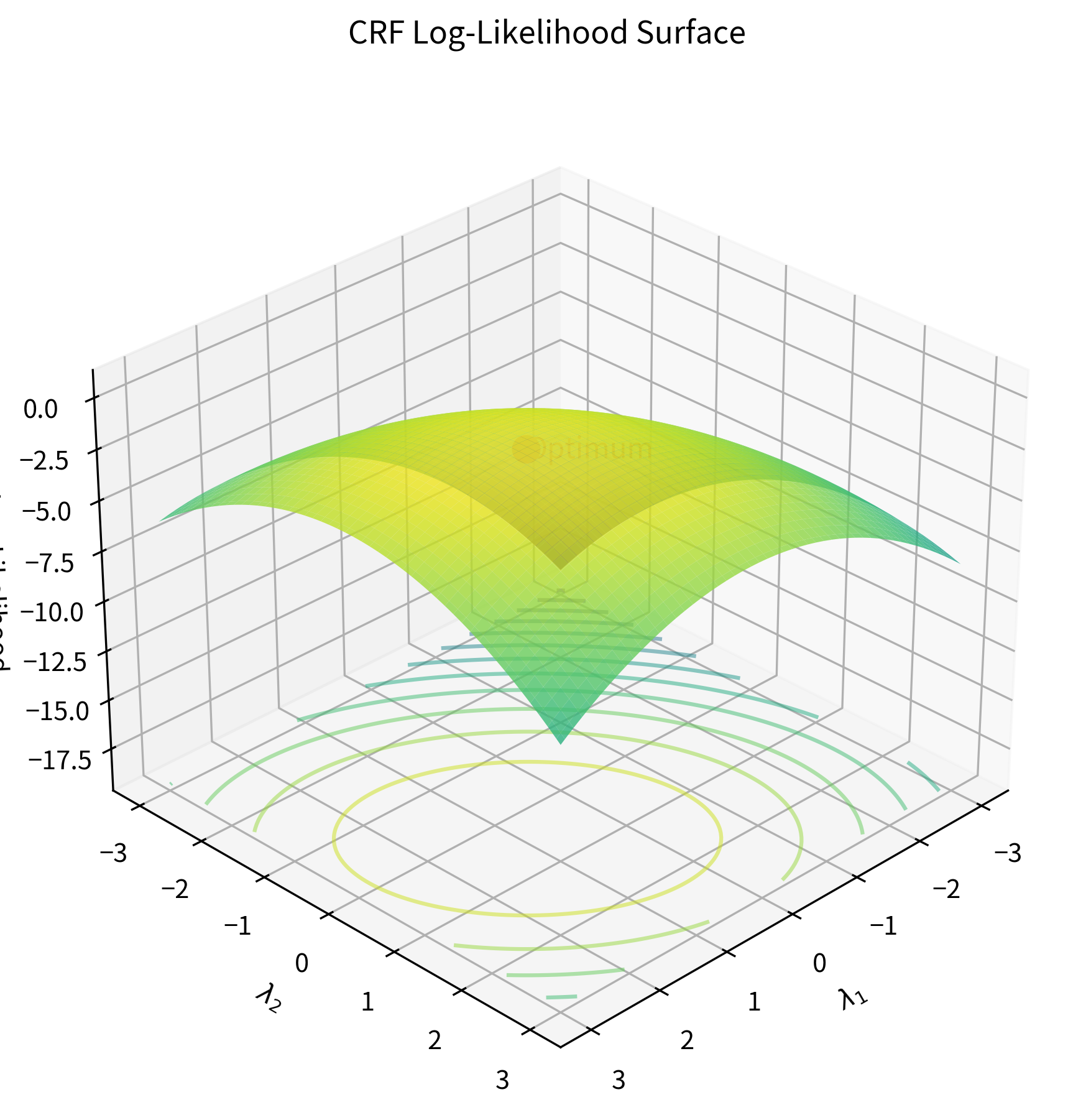

Let's visualize what this objective looks like for a simple case:

The log-likelihood function for CRFs has a crucial property: it is concave. This means there are no local maxima to get trapped in. Any hill-climbing algorithm will find the global optimum given enough iterations. This mathematical guarantee makes CRF training well-behaved compared to neural network training, where the loss landscape is riddled with local minima and saddle points.

The Forward-Backward Algorithm

Computing the partition function by enumerating all sequences is intractable. The forward-backward algorithm exploits the sequential structure of the model to compute it in polynomial time.

The key insight is that the CRF score decomposes into local terms. At each position , the contribution depends only on the label at and the label at . This Markov property enables dynamic programming: we can build up the sum over all sequences incrementally, position by position.

Forward Variables

The forward variable represents the sum of scores for all partial label sequences that end with label at position :

where:

- : all possible label sequences from position 1 to

- : constrained to end with label

- The summation accumulates scores of all paths reaching state at time

We compute forward variables recursively:

Base case (t = 1):

where is a special start symbol.

Recursive case:

This recursion says: to get the total score of paths ending in at position , sum over all possible previous labels , multiplying the forward score at (all paths ending in ) by the transition score from to .

The partition function is simply the sum of all forward variables at the final position:

Backward Variables

The backward variable represents the sum of scores for all partial sequences starting from position , given that position has label :

where is fixed.

Base case (t = T):

Recursive case:

Computing Marginal Probabilities

The forward and backward variables together give us the probability of any label at any position. The posterior marginal probability of label at position is:

And the probability of a specific transition from to at positions to :

where is the transition score matrix at position .

Let's implement the forward-backward algorithm:

Notice how the marginals sum to 1.0 at each position. This is because they represent the probability distribution over labels at that position, marginalized over all possible label sequences. The forward-backward algorithm computes these marginals in time, compared to for brute-force enumeration.

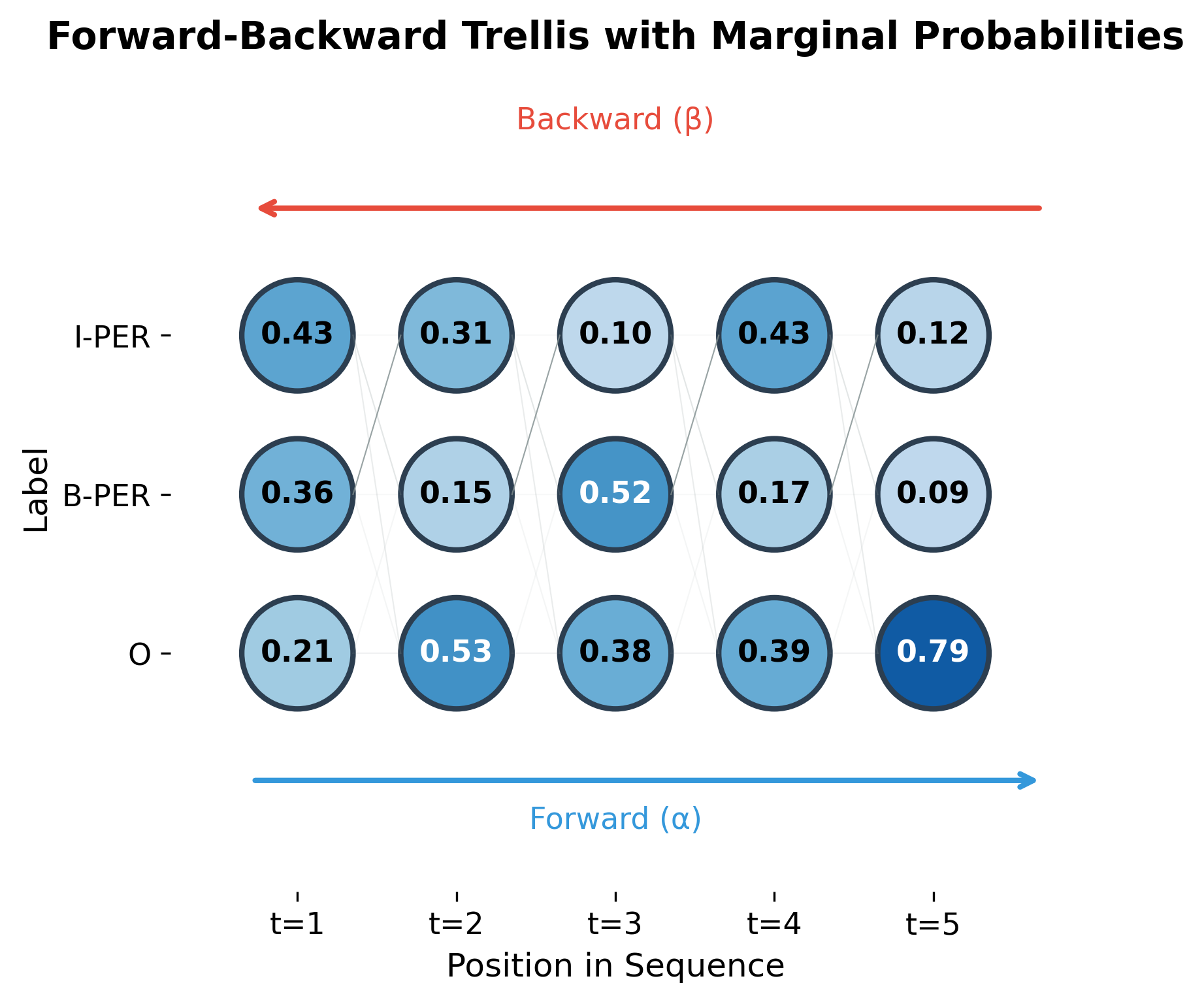

The trellis visualization shows how forward and backward passes combine. Each node's color intensity represents its marginal probability. States with high marginal probability (darker blue) are more likely to be part of the optimal sequence.

Gradient Computation

To optimize the log-likelihood, we need its gradient with respect to each weight . The gradient has an elegant form that emerges from the structure of the CRF.

Taking the derivative of the log-likelihood for a single example:

where:

- The first term is the observed feature count: how often feature fires on the correct label sequence

- The second term is the expected feature count: the expected number of times feature would fire under the model's current probability distribution

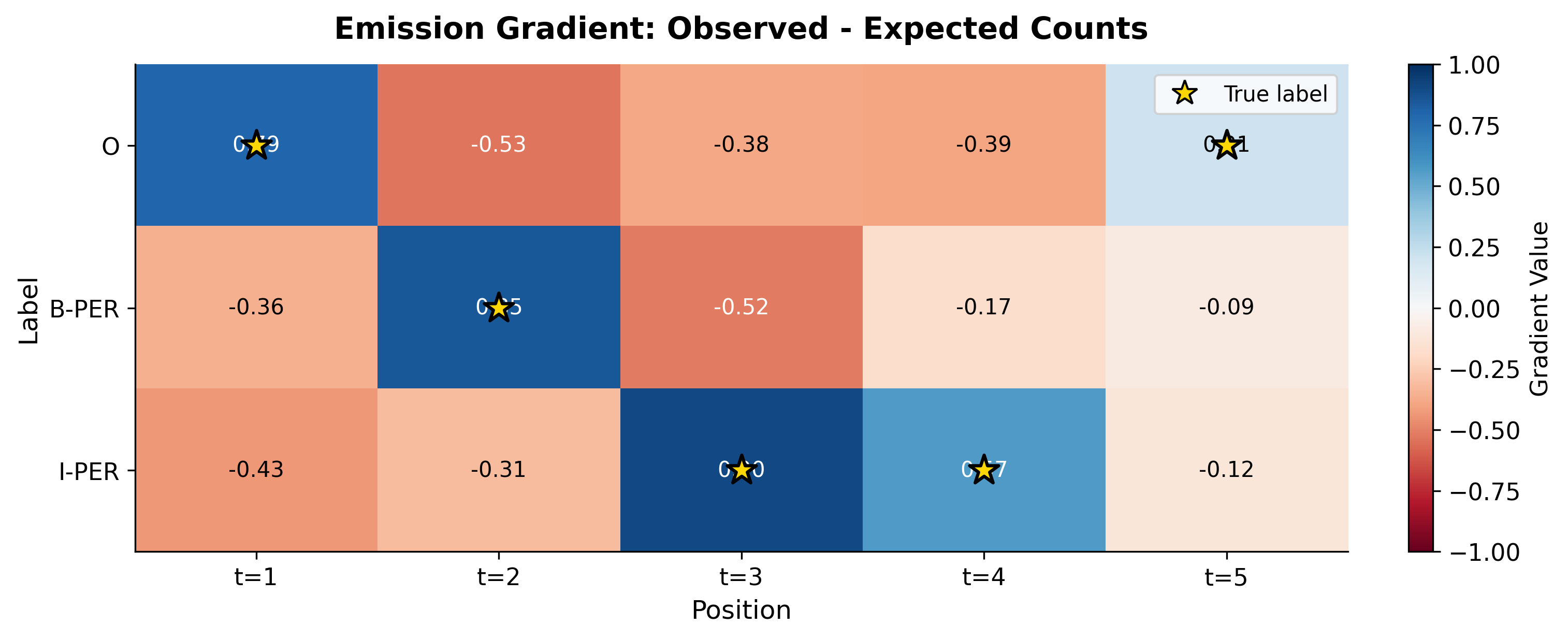

This gradient has an intuitive interpretation:

- If a feature fires more often in the training data than the model expects, increase its weight (positive gradient)

- If a feature fires less often than expected, decrease its weight (negative gradient)

- When observed counts match expected counts, the gradient is zero (we've reached a stationary point)

Computing Expected Feature Counts

The expected feature count requires summing over all positions and all label pairs, weighted by their posterior probabilities:

The forward-backward algorithm gives us exactly what we need: the pairwise marginals .

The gradient reveals which adjustments would improve the model. Positive gradients at the true labels mean the model should increase those scores. Negative gradients at incorrect labels mean those should be suppressed. The transition gradient shows similar patterns: transitions that occurred in the true sequence but have low model probability will have positive gradients.

L-BFGS Optimization

Simple gradient descent can optimize the CRF objective, but it converges slowly. Each step moves in the direction of the gradient, but the step size is tricky to tune: too large and you overshoot, too small and you crawl toward the optimum.

L-BFGS (Limited-memory Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno) is a quasi-Newton method that approximates the curvature of the objective function. Instead of using only the gradient direction, it uses gradient history to estimate how the objective curves in different directions, enabling larger steps in flat directions and smaller steps in steep directions.

L-BFGS is a quasi-Newton optimization algorithm that uses a limited memory approximation to the inverse Hessian matrix. It converges much faster than gradient descent for convex problems like CRF training, typically requiring 50-200 iterations instead of thousands.

The key advantages of L-BFGS for CRF training are:

- Faster convergence: Uses curvature information to take better steps

- No learning rate tuning: Line search automatically finds good step sizes

- Memory efficient: Stores only the last gradient pairs (typically ), not the full Hessian

- Robust: Works well on the convex CRF objective without careful hyperparameter tuning

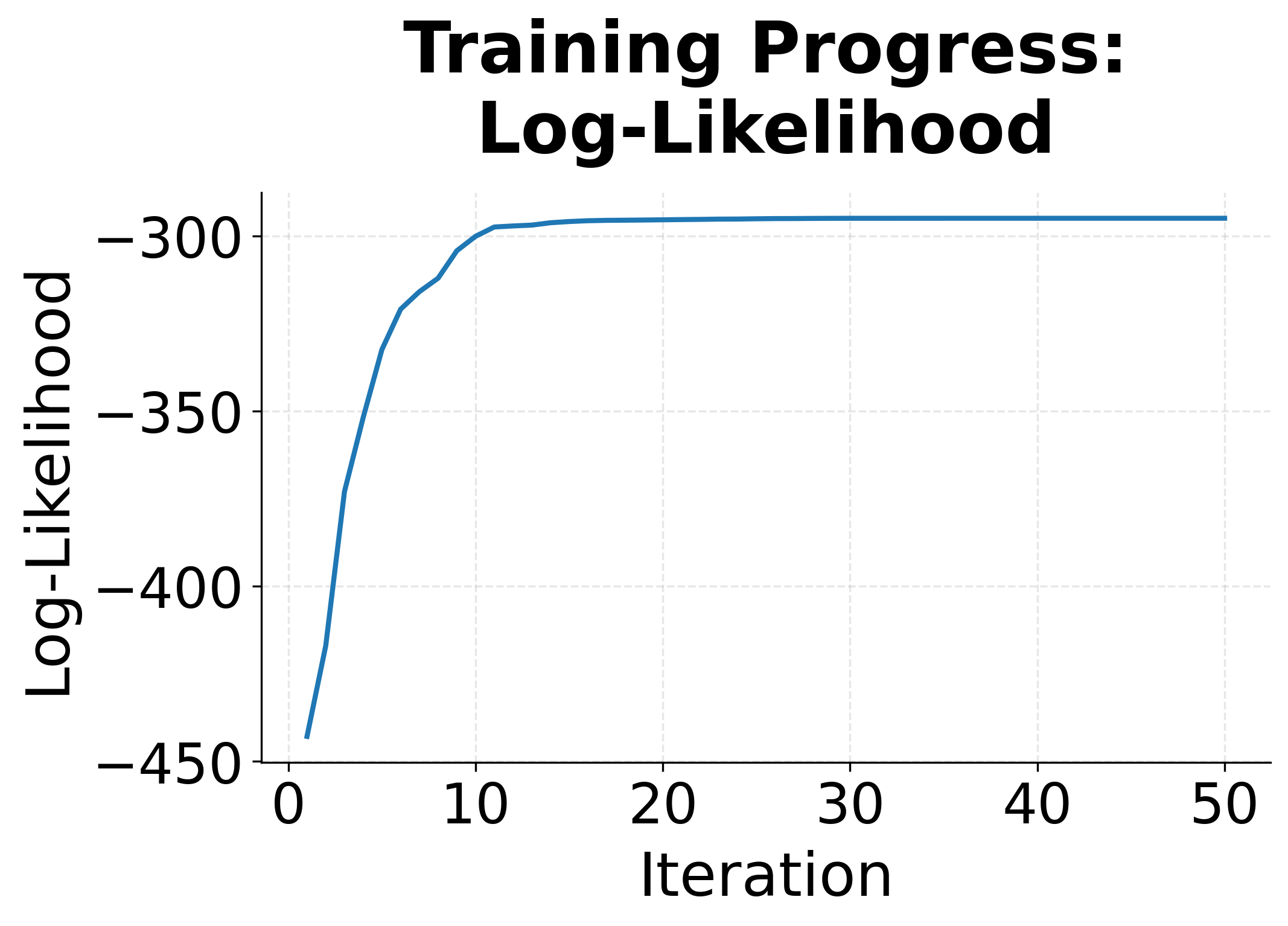

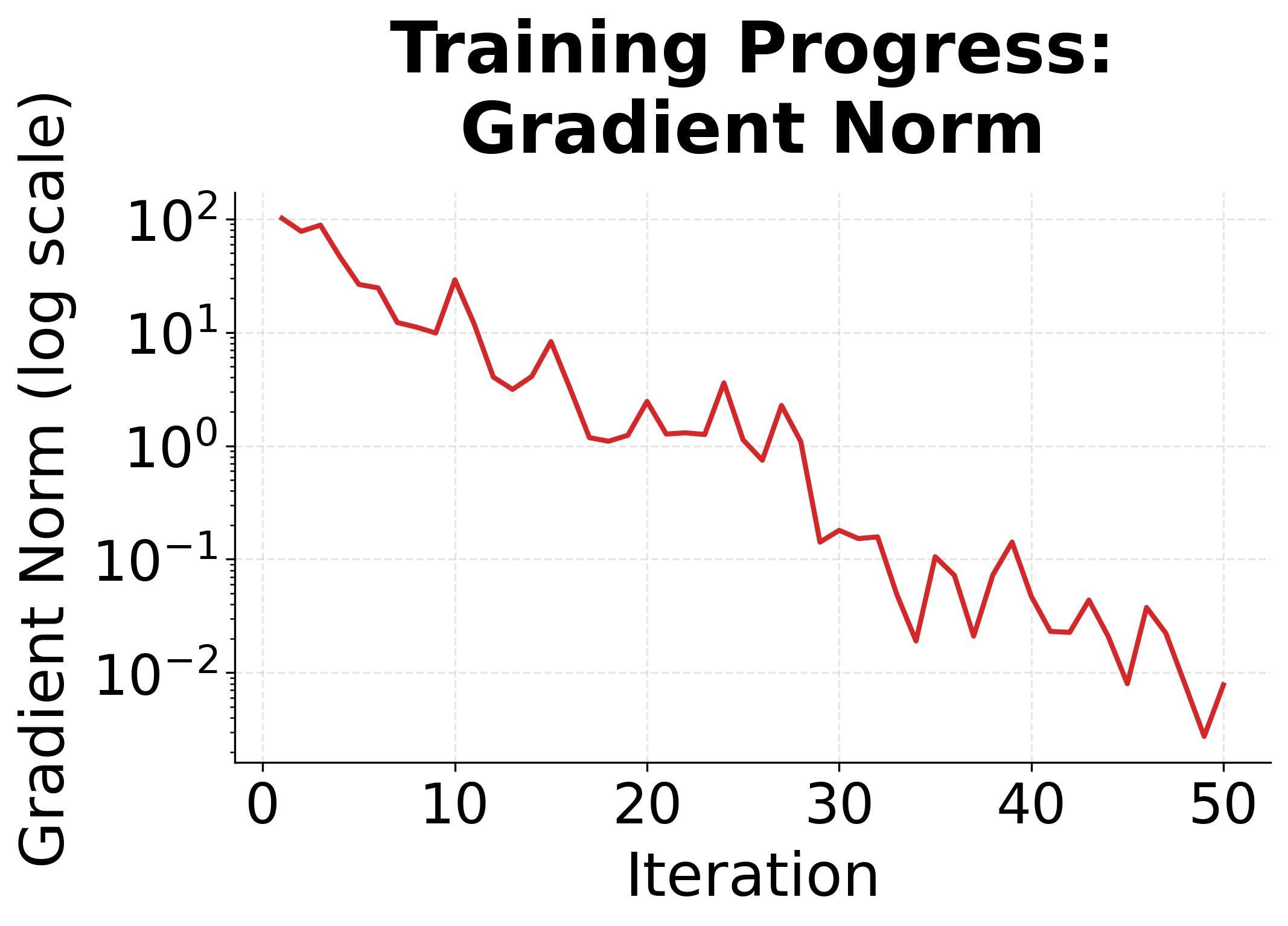

The convergence plots show the characteristic behavior of L-BFGS on a convex problem. The log-likelihood rises steeply at first, then levels off as we approach the optimum. The gradient norm drops exponentially, indicating we're getting closer to a point where the gradient is zero.

Feature Template Design

CRF features are the heart of the model. Well-designed features capture the patterns that distinguish correct label sequences from incorrect ones. Feature templates define how to extract features from the input, and the CRF learns which features matter most.

A feature template is a pattern that generates binary features from observations. For example, the template "current word = X" generates one feature for each unique word X in the vocabulary. Templates let you define feature types; the actual features are instantiated from training data.

Common Feature Types

Features for sequence labeling typically fall into several categories:

- Lexical features: The word itself, lowercase form, word shape (capitalization pattern)

- Contextual features: Surrounding words in a window

- Morphological features: Prefixes, suffixes, presence of digits or punctuation

- Part-of-speech features: POS tags from a tagger (if available)

- Transition features: Combinations of previous and current labels

The feature extractor captures patterns that are predictive of entity labels. Title-cased words are often names. Words ending in "-ia" might be locations. Words preceded by "at" might be organizations. The CRF learns which of these patterns are actually reliable predictors.

Feature Templates in Practice

Real NER systems use extensive feature templates. The sklearn-crfsuite library provides a convenient way to train CRFs with custom features:

The learned feature weights reveal what the CRF considers important. High positive weights for "word.istitle=True" on B-PER indicate that title-cased words are strong signals for person names. The CRF automatically discovers these patterns from the training data.

Regularization

Without regularization, CRF training can overfit to the training data. If a feature appears only once in training and perfectly predicts a label, the optimal weight is infinity. Regularization prevents extreme weights and improves generalization.

Regularization adds a penalty term to the objective function that discourages large parameter values. This prevents overfitting by trading off training set fit against model complexity.

L1 and L2 Regularization

The regularized log-likelihood objective is:

where:

- : the original log-likelihood

- : L1 regularization coefficient (larger = less regularization)

- : L2 regularization coefficient (larger = less regularization)

- : absolute value of weight (L1 penalty)

- : squared weight (L2 penalty)

L1 and L2 regularization have different effects:

| Regularization | Penalty | Effect | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Drives weights to exactly zero | Feature selection, sparse models | |

| L2 | Shrinks all weights toward zero | General regularization | |

| L1 + L2 | Both | Combines sparsity with shrinkage | Often works best in practice |

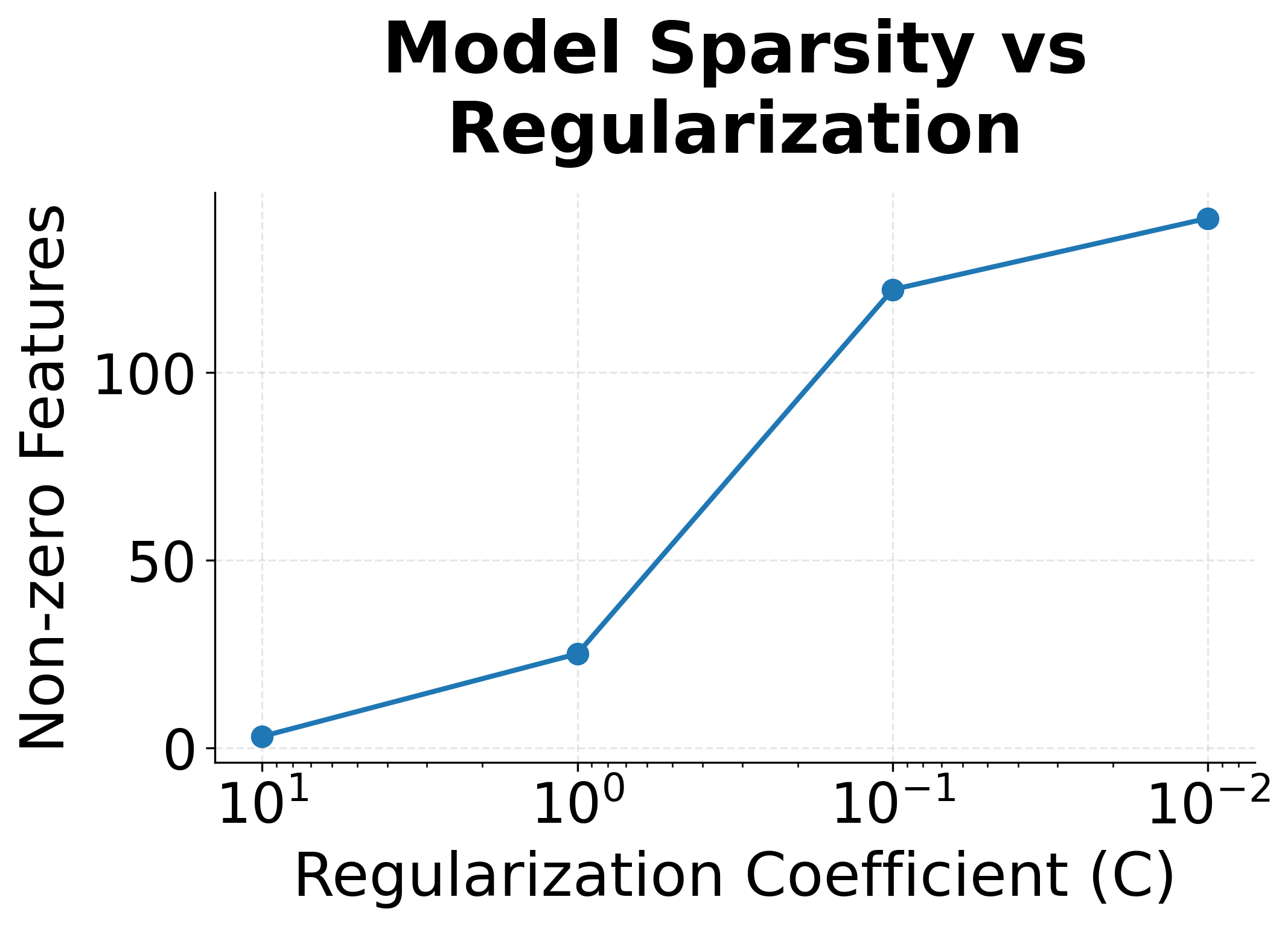

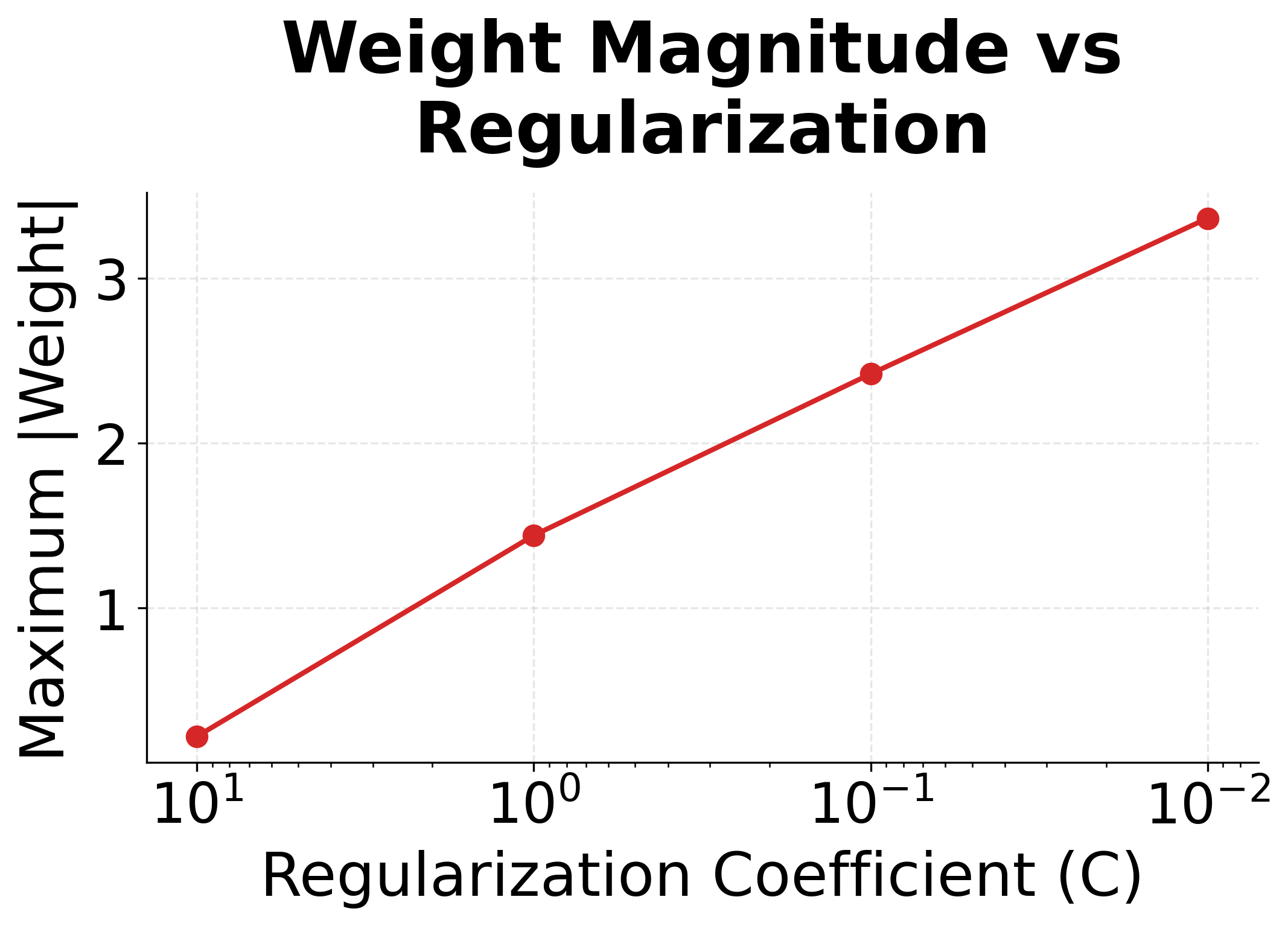

The regularization plots show clear trends. With strong regularization (small C), many features get zeroed out, creating a sparse model that uses only the most informative features. Maximum weight magnitudes also decrease, preventing the model from over-relying on any single feature.

Training a Complete NER Model

Let's put everything together and train a CRF on a real NER dataset:

The trained CRF achieves reasonable performance even on this limited training set. The model correctly identifies many entities by learning patterns from the feature templates. Errors often occur at entity boundaries or with rare entity types that don't have enough training examples.

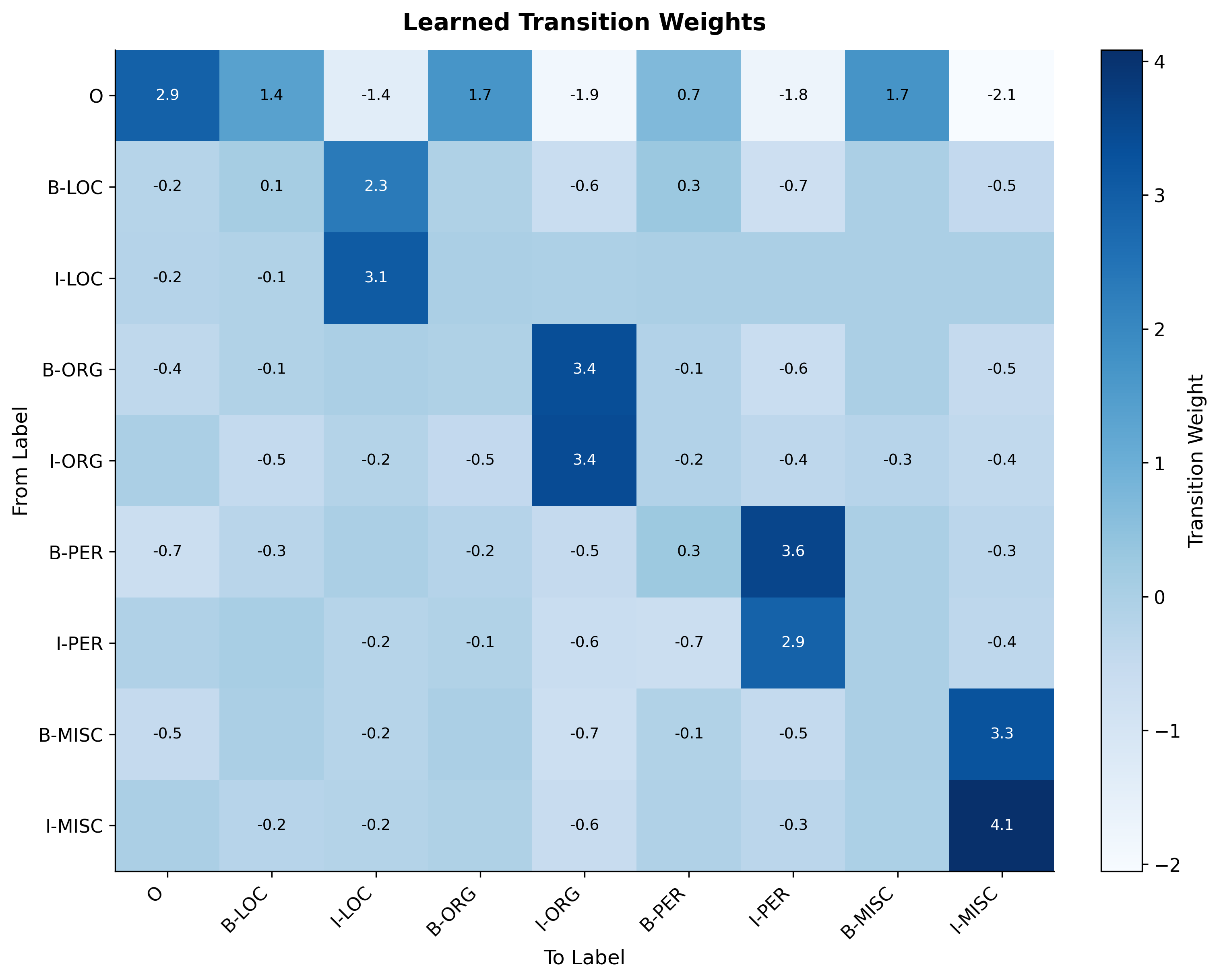

The transition matrix reveals that the CRF has learned BIO constraints. High weights appear for valid transitions like O→B-LOC (starting a location entity) and B-LOC→I-LOC (continuing a location). Low or negative weights appear for invalid transitions like O→I-LOC (continuation without a beginning).

Limitations and Impact

CRF training has both strengths and limitations that shape when and how to use these models effectively.

The forward-backward algorithm makes CRF training tractable, but it still requires time per sequence. For tasks with many labels like fine-grained NER or semantic role labeling, this quadratic scaling becomes expensive. A sequence with 50 labels and 100 tokens requires computing 250,000 transition scores per training example. This cost compounds across thousands of training sentences and hundreds of optimization iterations.

Feature engineering remains both a strength and weakness. Hand-crafted features like word shapes, prefixes, and context windows capture linguistic knowledge effectively. But designing features requires domain expertise and extensive experimentation. Features that work well for English NER may perform poorly on German or Japanese. This manual effort contrasts sharply with neural approaches that learn representations automatically from raw text.

CRFs also struggle with long-range dependencies. The Markov assumption means each label depends only on the immediately preceding label. If a token's correct label depends on context five words away, the CRF must propagate that information through intervening transitions. In practice, this limits how much global context the model can exploit.

Despite these limitations, CRFs made sequence labeling practical before deep learning. Their contribution extends beyond the models themselves to the training paradigms they established. The idea of discriminatively training structured models, using dynamic programming for efficient inference, and designing features to capture domain knowledge influenced subsequent developments in neural NLP. Modern neural CRF layers, which place a CRF on top of BiLSTM or transformer encoders, combine learned representations with the structured prediction framework that CRFs pioneered.

For practitioners today, CRFs remain valuable in several scenarios: when training data is limited (hundreds rather than thousands of examples), when interpretability matters (examining feature weights reveals model behavior), when computational resources are constrained (CRFs train on CPUs in minutes), or as components in hybrid systems (neural encoders + CRF output layers).

Summary

Training Conditional Random Fields requires balancing computational efficiency with model expressiveness. The key ideas covered in this chapter are:

-

Log-likelihood objective: CRF training maximizes the probability of correct label sequences. The objective is concave, guaranteeing a unique global optimum.

-

Forward-backward algorithm: Dynamic programming computes the partition function and marginal probabilities in time, making training tractable despite the exponential number of possible label sequences.

-

Gradient computation: The gradient equals observed feature counts minus expected feature counts. When these match, the model has converged.

-

L-BFGS optimization: Quasi-Newton methods converge much faster than gradient descent by approximating curvature information. Most CRF implementations use L-BFGS by default.

-

Feature templates: Hand-designed features capture patterns like word shapes, context windows, and morphological properties. Good features are essential for CRF performance.

-

Regularization: L1 and L2 penalties prevent overfitting by discouraging extreme weights. L1 produces sparse models; L2 shrinks all weights toward zero.

CRFs established the foundation for structured prediction in NLP. While neural approaches now dominate, the principles of discriminative training, dynamic programming, and structured output remain central to modern sequence labeling systems.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about CRF training.

Comments