Learn to train custom tokenizers with HuggingFace, covering corpus preparation, vocabulary sizing, algorithm selection, and production deployment.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Tokenizer Training

Introduction

Training a tokenizer is the first step in building any language model. Before a single weight is learned, you must decide how to split text into tokens. This decision affects everything downstream: vocabulary size determines embedding table dimensions, token boundaries influence what patterns the model can learn, and the training corpus shapes which subwords exist in the vocabulary.

In previous chapters, we explored the algorithms behind subword tokenization: BPE, WordPiece, and Unigram. Now we turn to the practical side: how do you train a tokenizer from scratch? What corpus should you use? How do you choose vocabulary size? And once trained, how do you save, load, and version your tokenizer for production use?

This chapter walks through the complete tokenizer training pipeline using the HuggingFace tokenizers library, the industry standard for fast, flexible tokenizer training. By the end, you'll be able to train custom tokenizers for any domain, from legal documents to code to biomedical text.

Corpus Preparation

The quality of your tokenizer depends entirely on the quality of your training corpus. A tokenizer learns which character sequences are common enough to become tokens. If your corpus doesn't represent your target domain, the tokenizer will produce suboptimal splits at inference time.

The collection of text used to learn tokenizer vocabulary. The corpus determines which subwords are considered frequent enough to become tokens, so it should be representative of the text the tokenizer will process at inference time.

What Makes a Good Training Corpus?

A well-chosen corpus has three properties:

- Representative: It should match the distribution of text you'll tokenize in production. Training on Wikipedia won't help if you're tokenizing tweets.

- Large enough: You need sufficient data for frequency statistics to be meaningful. For general-purpose tokenizers, this means billions of tokens. For domain-specific tokenizers, millions may suffice.

- Clean: Noise in the corpus becomes noise in the vocabulary. HTML artifacts, encoding errors, and garbage text waste vocabulary slots on useless tokens.

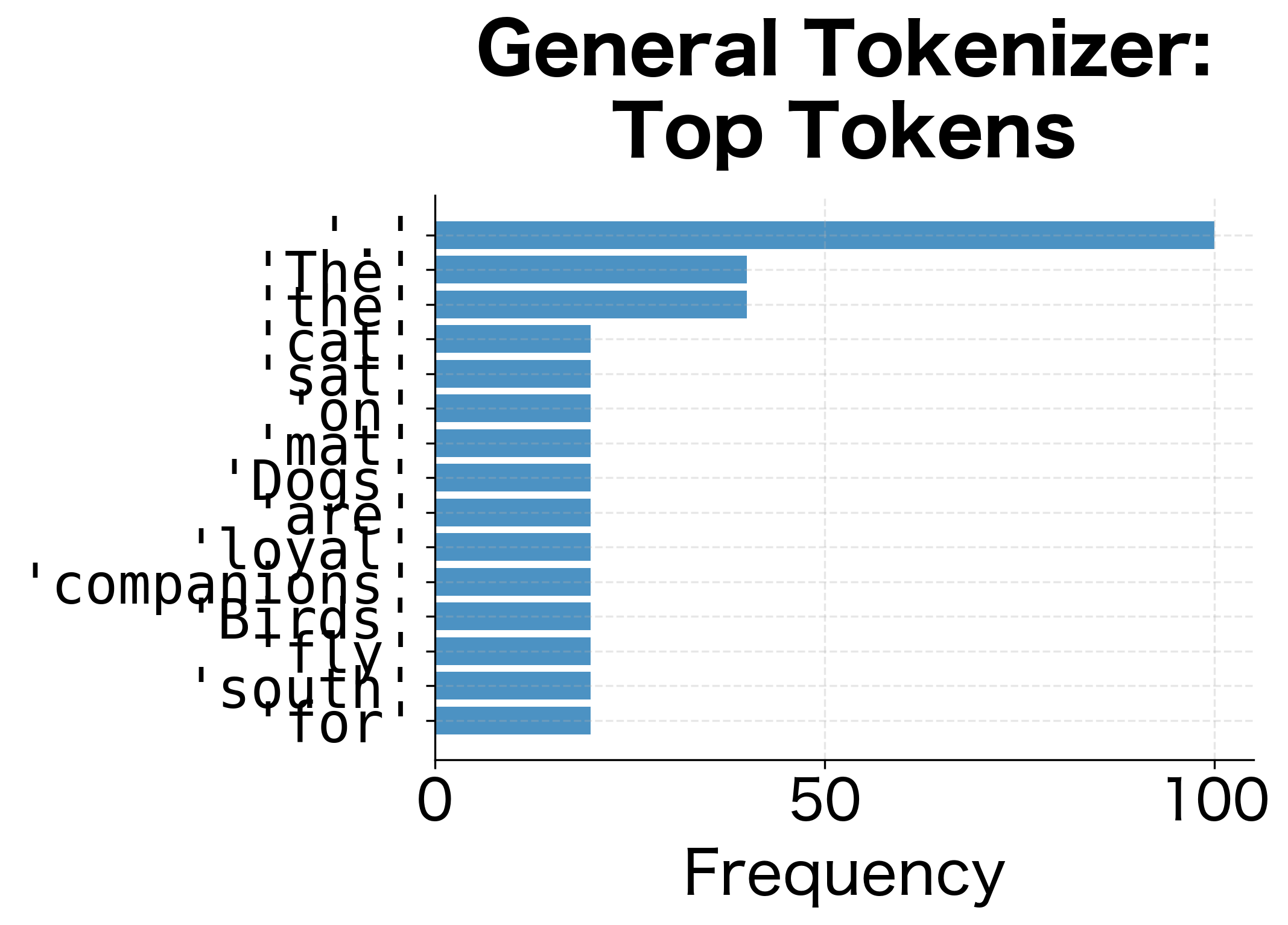

Let's examine how corpus choice affects the learned vocabulary:

The difference is striking. The general-purpose tokenizer, trained on natural language, fragments the code into many small pieces because it never learned that def, return, or None are meaningful units. The code tokenizer recognizes these as complete tokens, producing a more compact and semantically meaningful representation.

Let's see this difference across multiple code snippets:

| Code Snippet | General Tokenizer | Code Tokenizer | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

def sum(a, b): | 9 | 4 | 56% |

return x + y | 7 | 3 | 57% |

for i in range(10): | 11 | 4 | 64% |

import numpy as np | 8 | 3 | 63% |

class Model: | 6 | 2 | 67% |

Corpus choice has a dramatic effect on tokenization efficiency. For code, the domain-specific tokenizer reduces token counts by 50-70%, which translates directly to faster training and inference.

Preprocessing for Tokenizer Training

Before training, you typically preprocess the corpus to remove noise and normalize text. Common preprocessing steps include:

The preprocessing removed the HTML tags, collapsed multiple spaces into single spaces, and stripped the control characters. Notice how <p>Hello world!</p> became just Hello world!. This cleanup ensures your vocabulary contains meaningful tokens rather than HTML fragments or encoding artifacts. The specific preprocessing steps depend on your use case: code tokenizers might preserve certain control characters, while chat tokenizers might normalize emoji variants.

Vocabulary Size Selection

Vocabulary size is the most impactful hyperparameter in tokenizer training. It controls the tradeoff between sequence length and vocabulary coverage.

The total number of unique tokens in the tokenizer's vocabulary, including special tokens. Larger vocabularies produce shorter sequences but require more embedding parameters. Typical values range from 30,000 to 100,000 for general-purpose models.

The Vocabulary Size Tradeoff

Consider what happens at the extremes:

- Very small vocabulary (e.g., 256 bytes): Every word is split into many tokens, creating long sequences that are slow to process and hard for attention to span

- Very large vocabulary (e.g., 1 million tokens): Most words are single tokens, but the embedding table becomes enormous and rare tokens have poor representations

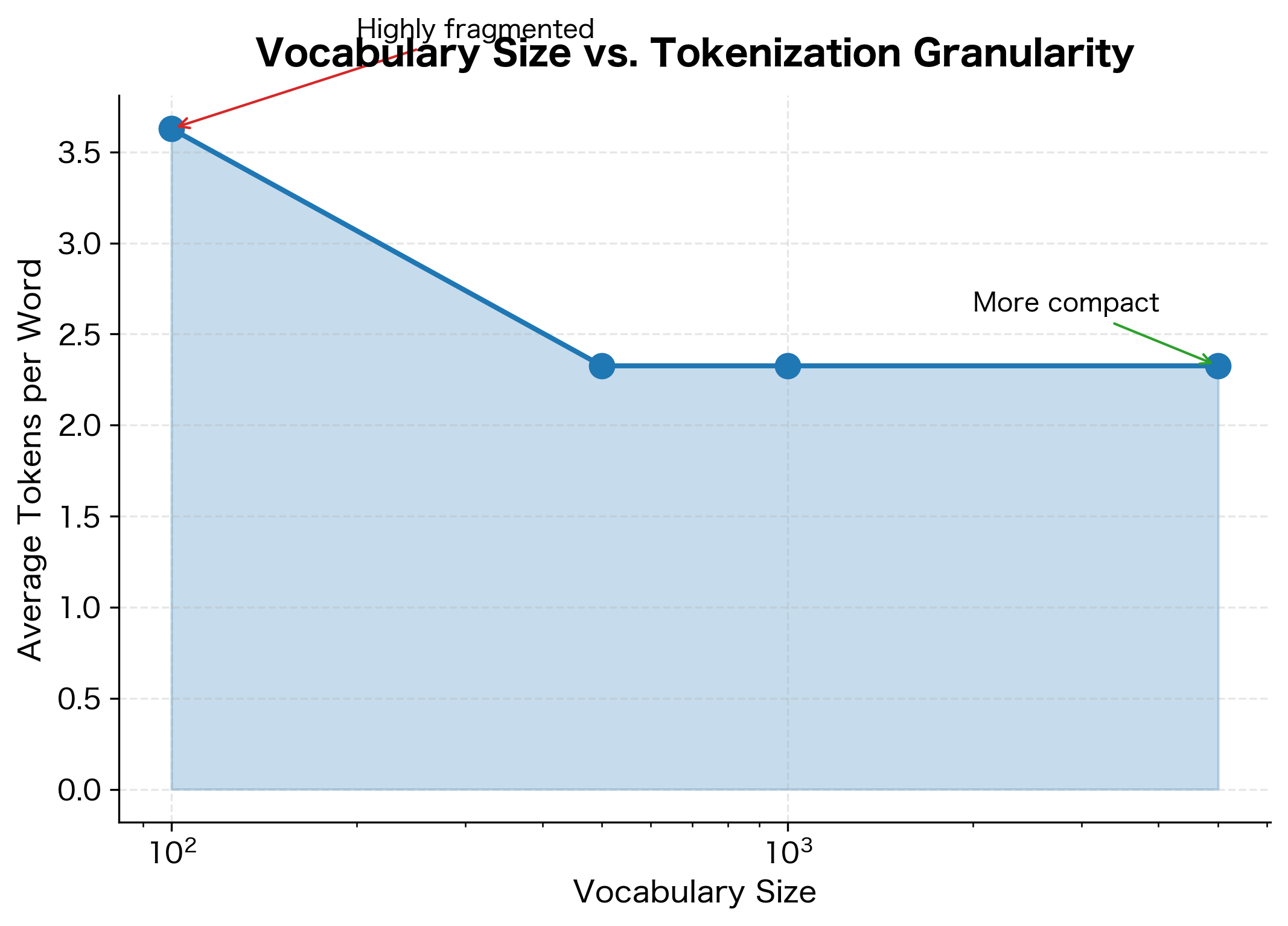

The sweet spot depends on your model size, training data, and target languages. Here's how vocabulary size affects tokenization:

The results demonstrate a clear inverse relationship between vocabulary size and token count. With only 100 vocabulary slots, common words like "Transformers" get split into many character-level tokens. As vocabulary size increases to 5,000, common words and morphemes become single tokens, dramatically reducing sequence length.

Let's visualize this relationship more systematically:

Guidelines for Vocabulary Size Selection

Production models use vocabulary sizes that balance efficiency and coverage:

| Model | Vocabulary Size | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-2 | 50,257 | Byte-level BPE, English-focused |

| GPT-4 | 100,277 | Expanded for multilingual and code |

| BERT | 30,522 | WordPiece, English uncased |

| LLaMA | 32,000 | SentencePiece, efficient for inference |

| T5 | 32,128 | SentencePiece Unigram |

For domain-specific models, smaller vocabularies often work well:

- Legal/medical domains: 16,000-32,000 (domain vocabulary is specialized but limited)

- Code models: 32,000-50,000 (need tokens for keywords, operators, common identifiers)

- Multilingual: 100,000+ (must cover multiple scripts and languages)

Training with HuggingFace Tokenizers

The HuggingFace tokenizers library provides a fast, flexible framework for tokenizer training. It supports BPE, WordPiece, and Unigram models with customizable pre-tokenization, normalization, and post-processing.

The Tokenizer Pipeline

A HuggingFace tokenizer consists of four components:

- Normalizer: Transforms text before tokenization (lowercasing, Unicode normalization, stripping accents)

- Pre-tokenizer: Splits text into words or word-like units before subword tokenization

- Model: The core algorithm (BPE, WordPiece, or Unigram) that splits words into subwords

- Post-processor: Adds special tokens and formats the output

Let's build a complete tokenizer with all components:

The normalizer processes text before any tokenization occurs. NFD normalization decomposes characters into base characters and combining marks, making it easier to strip accents consistently. Lowercasing reduces vocabulary size by treating "The" and "the" as the same token.

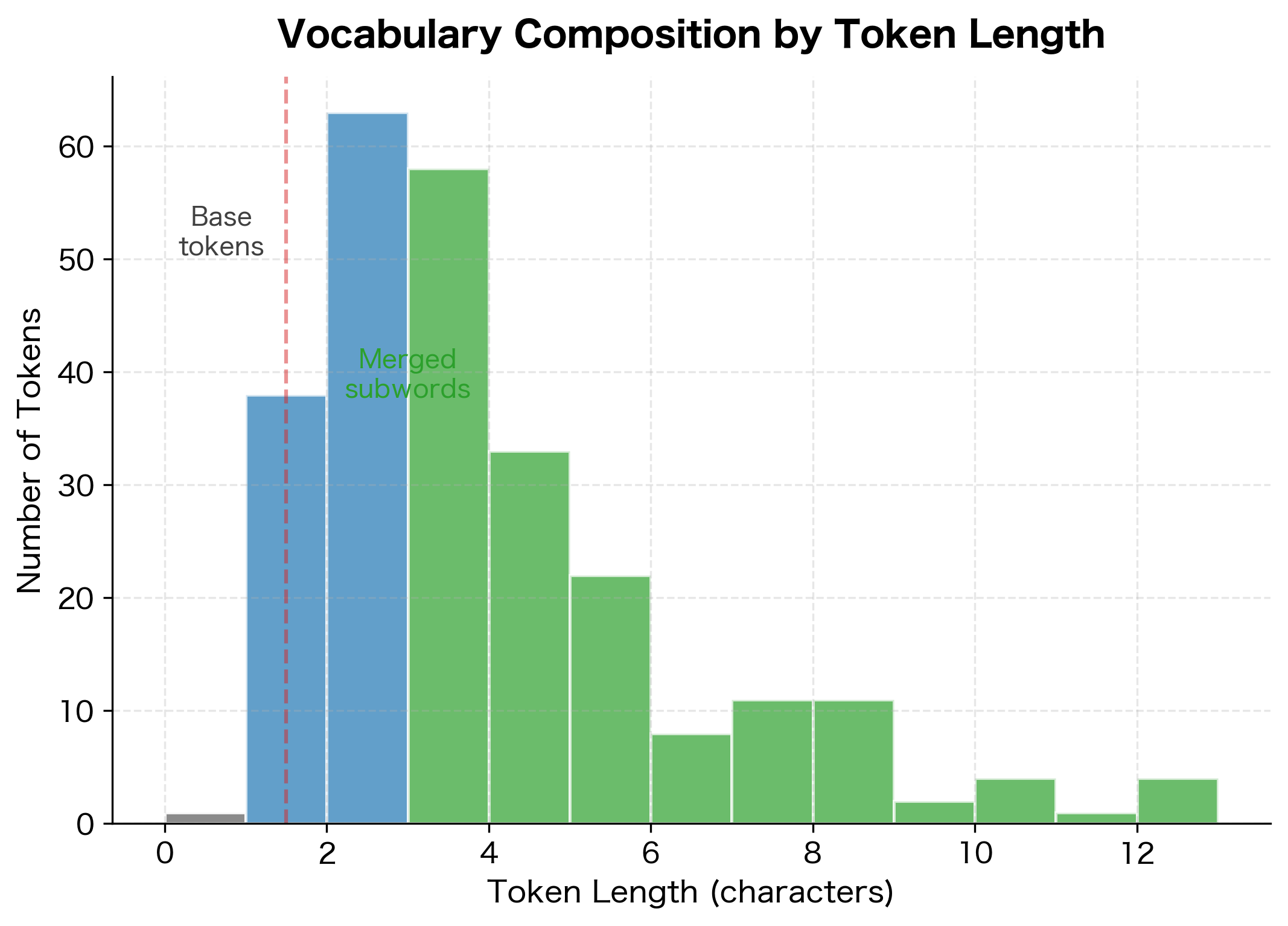

The vocabulary structure reveals the tokenizer's architecture. Special tokens occupy the first slots with reserved IDs (0-4). Next come the 256 byte-level base tokens that ensure any character can be represented. The remaining slots contain merged tokens: progressively longer sequences that the BPE algorithm identified as frequent in the training corpus. This byte-level encoding ensures the tokenizer can handle any input, even characters not seen during training.

The histogram reveals the vocabulary's layered structure. Single-character tokens form the base layer, guaranteeing universal coverage. Most merged tokens are 2-5 characters, representing common morphemes like "ing", "tion", and "pre". Longer tokens capture frequently occurring words that appear often enough in the corpus to earn dedicated vocabulary slots.

Adding Post-Processing

Post-processing adds special tokens that models expect. BERT-style models need [CLS] at the start and [SEP] between segments:

The post-processor automatically wraps the input with [CLS] and [SEP] tokens, matching the format expected by BERT and similar models.

Training Different Model Types

The tokenizers library supports three subword algorithms. Here's how to train each:

The three algorithms produce noticeably different segmentations for the same input. BPE tends to produce longer common subwords through greedy merging of frequent pairs. WordPiece often shows the ## prefix for continuation tokens within words, using likelihood-based scoring. Unigram may choose different boundaries based on its global probability optimization. Despite these differences, all three achieve the same goal: representing text with a fixed vocabulary of subword units.

Let's compare how these algorithms perform across multiple phrases:

While the differences between algorithms are often modest for individual phrases, they can be significant for specific words or domains. BPE's greedy merging sometimes captures longer subwords, while Unigram's probabilistic approach may find different optimal segmentations. In practice, the choice of algorithm matters less than vocabulary size and corpus quality.

Saving and Loading Tokenizers

Once trained, you need to save your tokenizer for later use. The HuggingFace tokenizers library provides multiple saving formats.

Saving to JSON

The native format saves the complete tokenizer configuration as JSON:

The tokenizer serializes to a compact JSON file containing all necessary components. The model key stores vocabulary and merge rules, while normalizer, pre_tokenizer, and post_processor store the processing pipeline configuration. This self-contained file enables exact reproduction of the tokenizer on any system.

Loading a Saved Tokenizer

Loading is straightforward:

The loaded tokenizer produces identical output to the original, confirming that all vocabulary entries and configuration were preserved. This reproducibility is essential for production deployments where tokenizers are saved once and loaded many times across different systems.

Saving for Transformers Integration

To use your tokenizer with the HuggingFace Transformers library, save it in a format that PreTrainedTokenizer can load:

The Transformers format creates multiple files: tokenizer.json contains the full tokenizer configuration, tokenizer_config.json stores metadata like special token mappings, and special_tokens_map.json explicitly lists all special tokens. This format integrates seamlessly with the Transformers library:

Loading via AutoTokenizer demonstrates full compatibility with the Transformers ecosystem. The tokenizer now works with any Transformers model that expects the same vocabulary and special token configuration.

Tokenizer Versioning

Tokenizers are a critical part of your model's reproducibility. Changing the tokenizer after training, even slightly, can break your model. A token ID that meant "the" during training might mean something entirely different with a new tokenizer.

Why Versioning Matters

Consider what happens if you modify your tokenizer:

- Adding tokens: New token IDs are outside the embedding table's range, causing index errors

- Removing tokens: Embeddings for removed tokens are wasted; text containing them becomes [UNK]

- Reordering vocabulary: Token IDs change meaning, producing garbage outputs

The solution is to version your tokenizer alongside your model and never modify a tokenizer once training begins.

Versioning Strategies

There are several approaches to tokenizer versioning:

1. Hash-based versioning: Compute a hash of the vocabulary to detect changes:

The 12-character hash provides a unique fingerprint for this exact vocabulary. Comparing hashes is faster and more reliable than diffing full vocabulary files, especially for vocabularies with 50,000+ tokens.

2. Semantic versioning: Include version in the save path:

The metadata file records when the tokenizer was created, its vocabulary size, and the unique hash for verification. This information is invaluable for debugging issues months later when you need to confirm which tokenizer version was used for a particular model.

3. Model-bundled tokenizers: The safest approach is bundling the tokenizer with the model checkpoint:

Domain-Specific Tokenizers

Generic tokenizers trained on web text perform poorly on specialized domains. Legal documents, medical records, source code, and scientific papers all contain vocabulary that general tokenizers fragment into many subwords.

When to Train a Domain Tokenizer

Train a domain-specific tokenizer when:

- Your domain has specialized vocabulary (legal terms, chemical formulas, API names)

- General tokenizers produce excessive fragmentation on your text

- You want more efficient representations for downstream tasks

- You're training a model from scratch on domain data

Don't bother training a domain tokenizer when:

- You're fine-tuning an existing model (use its tokenizer)

- Your domain text is mostly standard language

- You have limited domain data (vocabulary statistics will be unreliable)

Training a Code Tokenizer

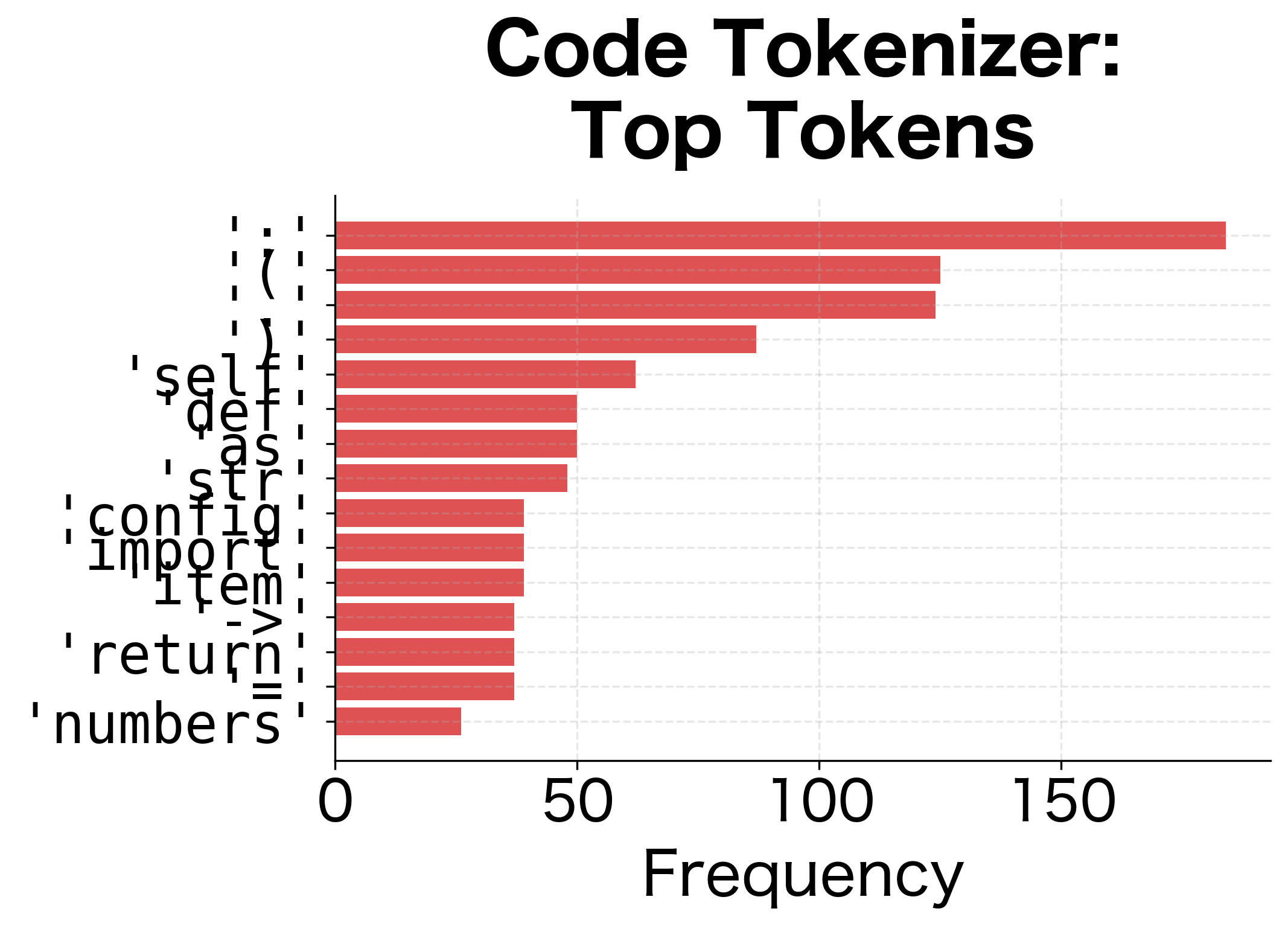

Let's train a tokenizer optimized for Python code:

The code tokenizer recognizes Python keywords like def, common patterns like ->, and frequently-used names like items and list as single tokens. This produces a more compact and meaningful representation.

Visualizing Domain Vocabulary Differences

Let's compare what tokens each tokenizer learns:

The vocabulary distributions reveal fundamentally different priorities. The general tokenizer learns common English words and function words. The code tokenizer learns Python syntax: parentheses, colons, keywords, and common identifier patterns.

Combining Domain and General Vocabulary

Sometimes you want a tokenizer that handles both domain-specific and general text. One approach is to train on a mixed corpus:

The mixed tokenizer finds a reasonable middle ground, handling both general English and code with moderate efficiency. Neither domain is tokenized as compactly as with a specialized tokenizer, but the combined vocabulary covers both adequately. This tradeoff is appropriate for models that need to process diverse inputs, such as coding assistants that must understand both natural language instructions and source code.

A Complete Training Pipeline

Let's put everything together into a complete tokenizer training pipeline:

The output shows the complete pipeline in action. Each sequence begins with token ID 2 (<s>) and ends with token ID 3 (</s>), matching the expected format for sequence-to-sequence models. The byte-level encoding handles punctuation and spaces cleanly, while the vocabulary captures common English words as single tokens.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Training tokenizers involves tradeoffs that affect downstream model performance. Understanding these limitations helps you make informed decisions.

The most significant limitation is corpus dependency. Your tokenizer's vocabulary is a frozen snapshot of the training corpus. If your production data differs significantly from your training corpus, you'll see excessive fragmentation. A tokenizer trained on English news articles will struggle with social media text full of emojis, hashtags, and informal spelling. The only solution is to ensure your training corpus is truly representative, or to retrain when your target distribution shifts substantially.

Vocabulary exhaustion is another practical concern. Once you've allocated vocabulary slots to special tokens and common subwords, rare but important terms may be fragmented. Domain-specific terminology often suffers: a medical tokenizer might perfectly handle "aspirin" but fragment "pembrolizumab" into many pieces because it didn't appear often enough in training. You can mitigate this by increasing vocabulary size, but this increases memory usage and may hurt generalization for rare tokens that get poor embedding estimates.

The cold start problem affects new domains. Training a good tokenizer requires substantial text, but when entering a new domain, you may not have enough data for reliable frequency statistics. In these cases, using a general-purpose tokenizer is often better than training a domain tokenizer on insufficient data.

Finally, tokenizer-model coupling creates maintenance challenges. Once you train a model with a specific tokenizer, you cannot change the tokenizer without retraining the model. This means tokenizer bugs or suboptimal vocabulary choices are locked in for the model's lifetime. Careful validation before training is essential, as is maintaining strict version control to ensure reproducibility.

Summary

Training a tokenizer is a foundational step that shapes everything downstream in your NLP pipeline. The key decisions are:

-

Corpus preparation: Your training corpus must represent your target domain. Preprocessing removes noise that would waste vocabulary slots on meaningless tokens.

-

Vocabulary size: Larger vocabularies produce shorter sequences but require more embedding parameters. Production models typically use 30,000-100,000 tokens, with domain-specific models often using smaller vocabularies.

-

Algorithm selection: BPE, WordPiece, and Unigram produce different tokenizations. BPE is most common for generative models; WordPiece powers BERT; Unigram is used in SentencePiece.

-

Saving and versioning: Always save your tokenizer alongside your model. Use hashing or semantic versioning to detect changes. Never modify a tokenizer after training begins.

-

Domain adaptation: Train specialized tokenizers when your domain has unique vocabulary that general tokenizers fragment poorly. Code, legal, medical, and scientific domains often benefit from custom tokenizers.

The HuggingFace tokenizers library provides a fast, flexible framework for all these tasks. Its modular design lets you customize normalization, pre-tokenization, the subword algorithm, and post-processing to match your exact requirements.

In the next chapter, we'll explore special tokens in depth: what they are, why models need them, and how to configure them for different tasks.

Key Parameters

The following parameters are the most important when training tokenizers with the HuggingFace tokenizers library:

BpeTrainer / WordPieceTrainer / UnigramTrainer

These trainer classes share the same core parameters for controlling vocabulary learning:

| Parameter | Description | Typical Values |

|---|---|---|

vocab_size | Target vocabulary size including special tokens. Larger values produce shorter sequences but require more memory. | 8,000-100,000 |

min_frequency | Minimum number of times a token must appear to be included in vocabulary. Higher values produce cleaner vocabularies but may miss rare but important tokens. | 2-5 |

special_tokens | List of tokens guaranteed to be in vocabulary with fixed IDs. Order matters: the first token gets ID 0. | ["[UNK]", "[PAD]", "[CLS]", "[SEP]", "[MASK]"] |

show_progress | Whether to display a progress bar during training. | True or False |

Pre-tokenizers

Pre-tokenizers split text into initial chunks before the subword algorithm runs:

| Pre-tokenizer | When to Use |

|---|---|

Whitespace() | Simple splitting on whitespace. Good for quick experiments. |

ByteLevel(add_prefix_space=True) | GPT-2 style. Ensures universal character coverage. Best for production. |

Metaspace() | SentencePiece style. Uses ▁ to mark word boundaries. Good for multilingual. |

Normalizers

Normalizers transform text before any splitting occurs:

| Normalizer | Effect |

|---|---|

NFC() / NFD() / NFKC() / NFKD() | Unicode normalization forms. NFC is most common for preserving characters; NFKC for compatibility normalization. |

Lowercase() | Converts all text to lowercase. Reduces vocabulary but loses case information. |

StripAccents() | Removes accent marks. Useful for ASCII-focused vocabularies. |

Sequence([...]) | Chains multiple normalizers in order. |

Post-processors

Post-processors add special tokens and format the final output:

| Post-processor | Purpose |

|---|---|

TemplateProcessing(single="[CLS] $A [SEP]", ...) | Adds special tokens around sequences. Configure for BERT-style ([CLS]/[SEP]) or GPT-style (<s>/</s>) formats. |

ByteLevel(trim_offsets=True) | Required when using byte-level pre-tokenization to properly handle token boundaries. |

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about tokenizer training.

Comments