Learn the BIO tagging scheme for named entity recognition, including BIOES variants, span-to-tag conversion, decoding, and handling malformed sequences.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

BIO Tagging

Sequence labeling tasks like named entity recognition face a fundamental challenge: how do you represent multi-word entities using per-token labels? The sentence "New York City is beautiful" contains three tokens that together form a single location entity. Assigning all three the label "LOC" creates ambiguity. Does "New" start a new entity, or does it continue one that began earlier? Are "New," "York," and "City" three separate locations, or one?

BIO tagging solves this problem elegantly. The scheme uses a small set of prefixes to encode entity boundaries directly in the labels. B marks the beginning of an entity, I marks inside (continuation), and O marks outside (no entity). With BIO tags, "New York City" becomes B-LOC I-LOC I-LOC, unambiguously marking a single three-token entity.

This chapter explores BIO tagging from its basic mechanics through practical implementation. You'll learn the standard BIO scheme and its variants, implement converters between span annotations and BIO tags, build decoders that extract entities from tagged sequences, and handle the edge cases that arise in real-world tagging scenarios.

The BIO Scheme

BIO tagging encodes entity boundaries through prefix annotations. Each token receives a label combining a position indicator (B, I, or O) with an entity type. The three positions work together to delimit entity spans without ambiguity.

BIO (Beginning-Inside-Outside) is a tagging scheme for sequence labeling where each token receives a label indicating its position relative to entity spans: B marks the first token of an entity, I marks subsequent tokens within the same entity, and O marks tokens outside any entity.

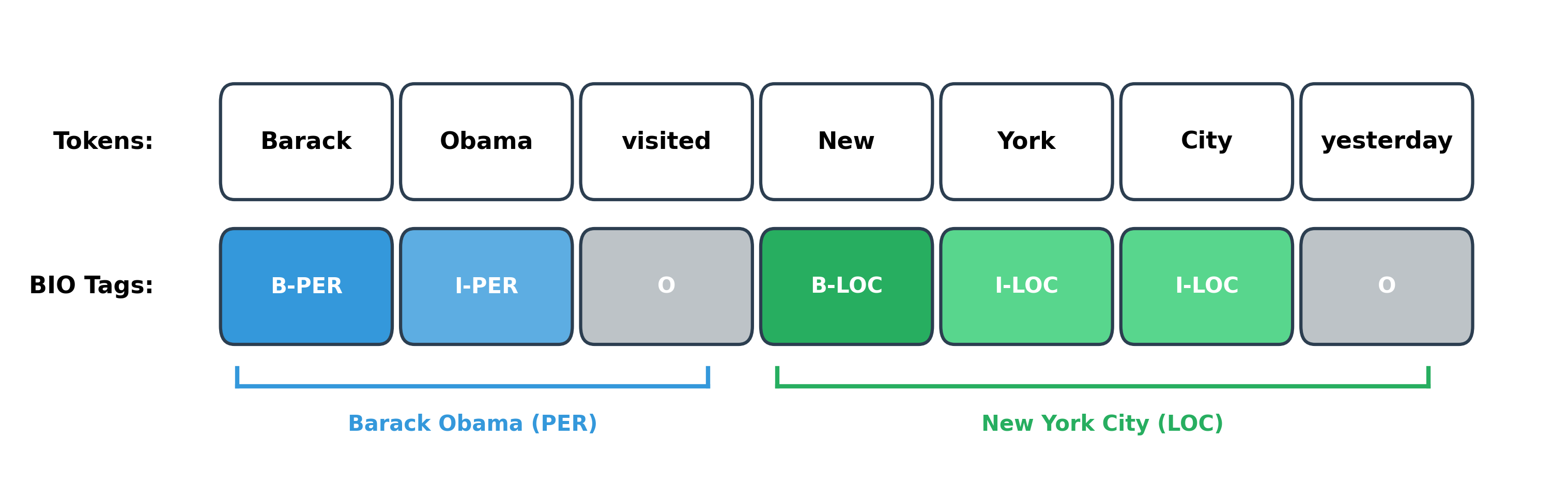

Let's see how BIO tagging works on a concrete example:

The BIO scheme achieves two critical goals. First, it marks entity boundaries explicitly. When you see a B tag, you know a new entity starts at that position. When you see an I tag following a B tag of the same type, you know the entity continues. Second, it handles adjacent entities correctly. If "Barack Obama" and "Michelle Obama" appeared consecutively without a gap, the B prefix on "Michelle" would clearly mark the second entity's start: B-PER I-PER B-PER I-PER.

Why Not Just Use Entity Types?

A simpler approach might label each token with just its entity type: PER, LOC, or O. Let's see why this fails:

Without the B prefix, we cannot determine where one entity ends and another begins. The simple scheme makes adjacent same-type entities indistinguishable from single multi-token entities. Real text contains many such cases: lists of names, multiple locations, consecutive organization mentions. BIO tagging handles all of them correctly.

The O Tag

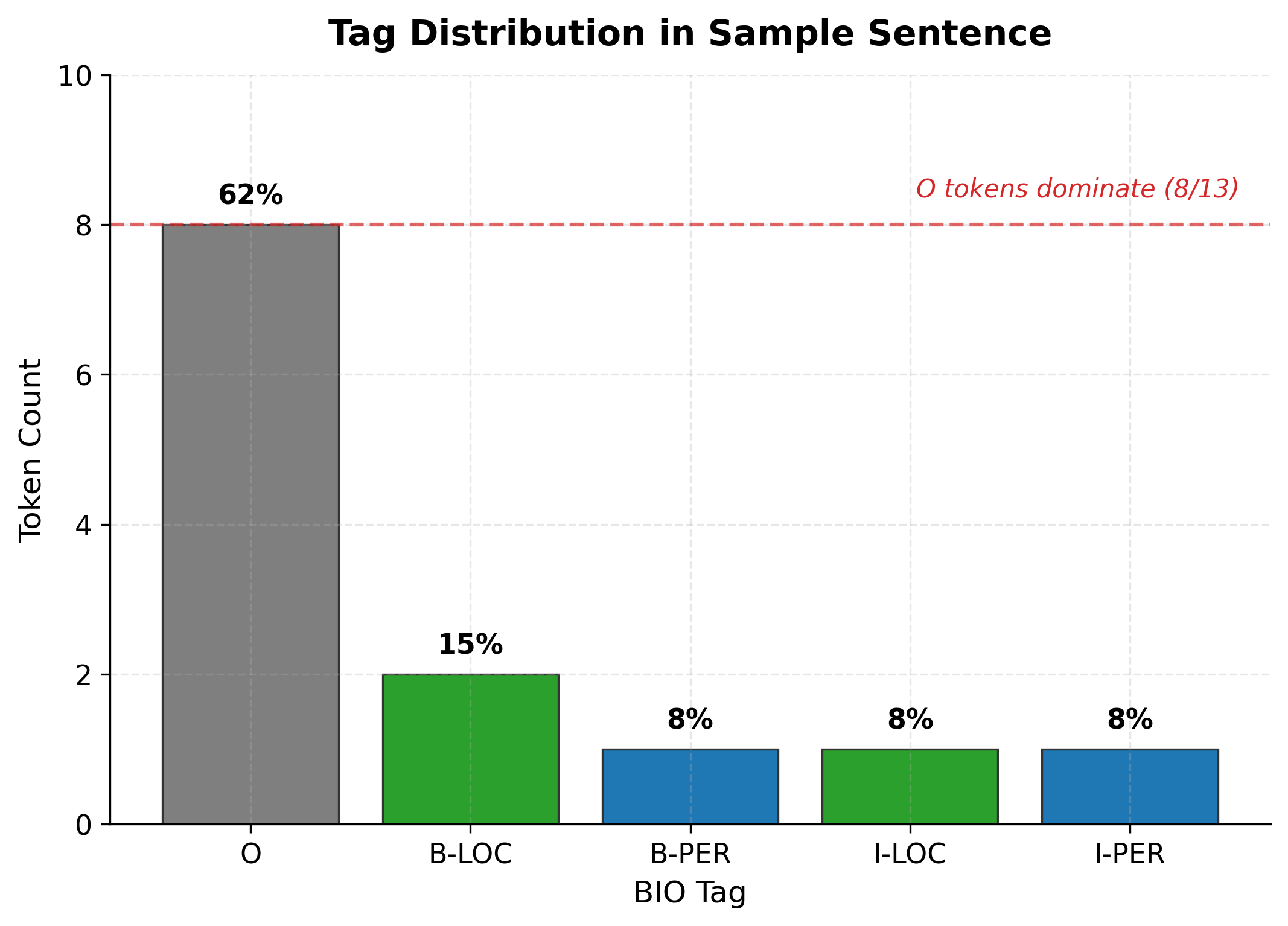

The O tag marks tokens that don't belong to any entity. It carries no suffix because "outside" is the only interpretation. In typical NER datasets, O tokens vastly outnumber entity tokens since most words in a sentence are not named entities:

This class imbalance, where O tokens dominate, is characteristic of sequence labeling tasks. Training algorithms must account for it, often through weighted loss functions or sampling strategies. The O tag's prevalence also means that a baseline of always predicting O achieves deceptively high accuracy but zero utility.

Extended Tagging Schemes

The basic BIO scheme is sufficient for many applications, but more complex annotation scenarios have motivated several extensions. These variants add prefixes to capture additional boundary information or handle special cases.

BIOES (BILOU) Scheme

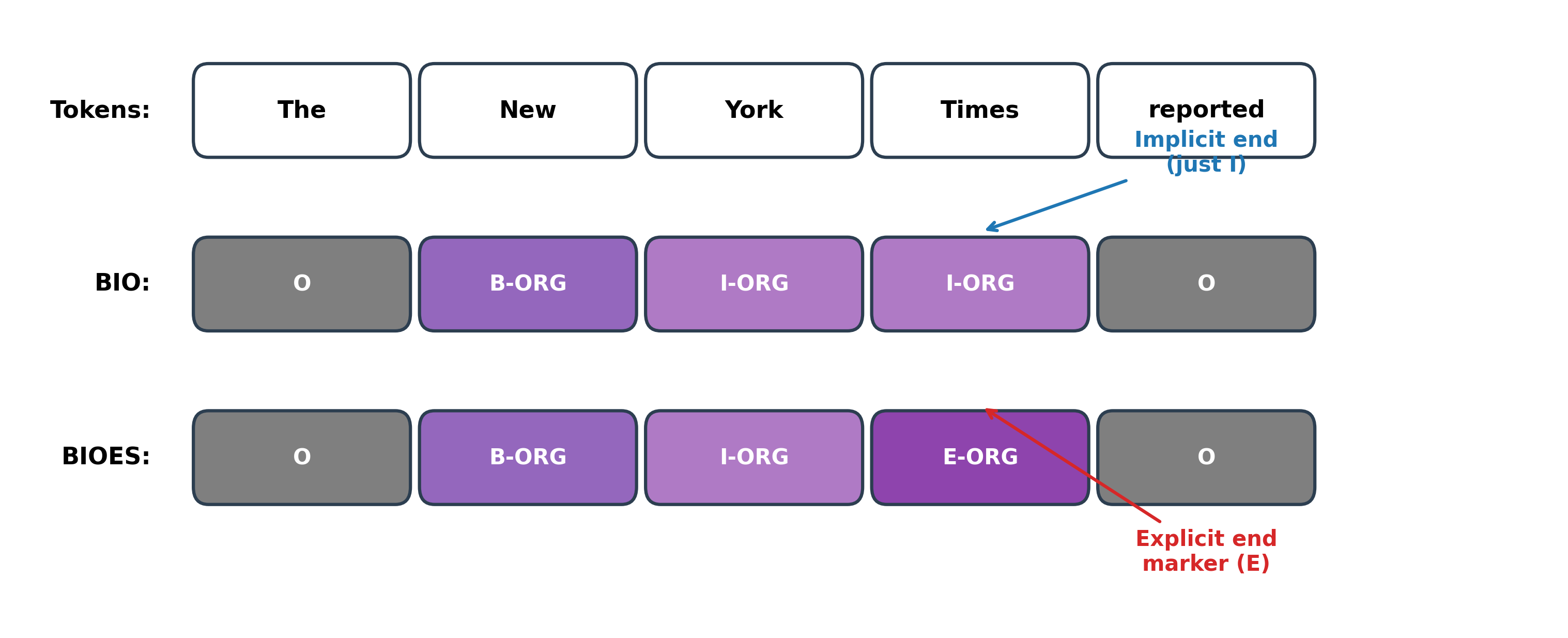

The BIOES scheme adds two more prefixes: E for the end of a multi-token entity and S for single-token entities. Some practitioners call this BILOU, using L (last) instead of E and U (unit) instead of S, but the semantics are identical.

Why add more tags? BIOES provides two benefits. First, the model learns to recognize entity endpoints explicitly rather than inferring them from tag transitions. Research has shown modest accuracy improvements from BIOES over BIO, particularly for longer entities where boundary precision matters. Second, BIOES makes certain decoding errors impossible: a valid BIOES sequence must have every B paired with an E (or be followed by more I tags and then E), and S must stand alone. These constraints can be enforced during decoding.

BMEWO and Other Variants

Researchers have proposed numerous other schemes for specialized scenarios:

The choice of scheme involves tradeoffs. More tags provide richer supervision but increase the number of classes the model must predict. For most NER tasks, BIO strikes a good balance, while BIOES offers marginal improvements when maximum boundary precision is critical.

Valid Tag Transitions

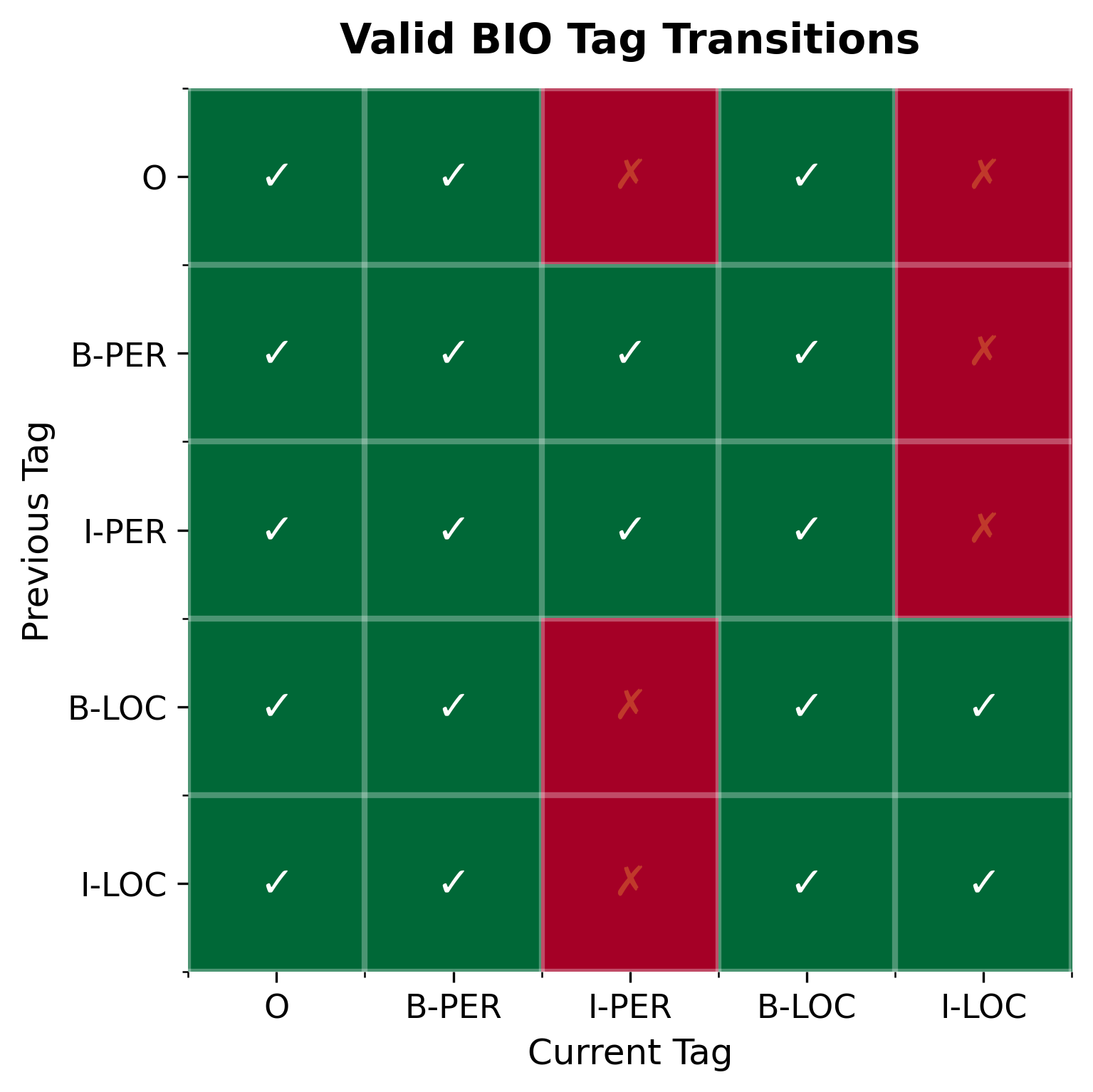

Understanding which tag sequences are valid helps when designing decoders or training models with constraints. Not all tag combinations make sense: an I-PER cannot follow a B-LOC, and an I tag cannot appear after O without a preceding B tag. The following heatmap shows which transitions are valid in the BIO scheme:

The key constraint is that I tags must match the type of their preceding B or I tag. An I-PER can follow B-PER or I-PER, but not B-LOC or I-LOC. This constraint can be enforced during inference using constrained beam search or CRF layers, improving the coherence of predicted sequences.

Converting Spans to BIO Tags

Annotation tools often store entity information as character or token spans rather than per-token labels. Converting these span annotations to BIO format is a common preprocessing step. Let's build a robust converter.

The converter handles the common case well. But real-world data presents edge cases: what happens with overlapping spans, single-token entities, or spans at sentence boundaries?

Single-token entities receive only a B tag since there's no continuation. Adjacent same-type entities each start with B, correctly distinguishing them. The converter handles boundary positions without special-casing.

BIOES Conversion

For applications requiring BIOES format, we extend the converter to track entity boundaries:

The BIOES output makes the entity endpoint explicit: "Times" receives E-ORG rather than I-ORG, marking it as the final token.

Decoding BIO Tags to Spans

The inverse operation extracts entity spans from a sequence of BIO tags. This is essential for evaluating model predictions and converting output to a usable format. The decoder must handle both well-formed and malformed tag sequences.

The decoder maintains state across tokens, tracking whether we're inside an entity and of what type. Key transitions occur when we encounter a B tag (start new entity), an O tag (end current entity), or reach the sequence end.

Handling Malformed Sequences

Model predictions don't always produce valid BIO sequences. Common errors include I tags without a preceding B tag and type mismatches where I-LOC follows B-PER. A robust decoder must handle these gracefully:

Our decoder applies sensible recovery strategies. Orphan I tags are treated as beginning a new entity. Type mismatches close the previous entity and start a fresh one. Consecutive B tags produce separate single-token entities. These choices maximize recall at the cost of some precision, which is often preferable for downstream error analysis.

BIOES Decoding

Decoding BIOES is slightly more complex but follows the same principles. The S and E tags provide additional boundary information:

The S tags directly produce single-token entities, while B-E pairs define multi-token spans. This explicit boundary marking simplifies validation and can catch more prediction errors.

Tag Consistency and Validation

Real-world tagging systems produce inconsistent output. A well-designed pipeline includes validation to detect problems and, where possible, repair them. Let's build a validator and repair function.

Once we've identified errors, we can attempt repairs. The repair strategy depends on the application. Conservative approaches leave errors in place for manual review. Aggressive approaches apply heuristics to fix common patterns:

The repair function transforms orphan I tags into B tags and creates new entity boundaries at type mismatches. These are common patterns in model output, where the model may predict the correct type but miss a boundary.

Multi-Label BIO Tagging

Standard BIO tagging assumes each token belongs to at most one entity. But some applications require overlapping annotations. Consider "Bank of America," which might be tagged as both an organization (the company) and a location (America is a place). Nested named entities present similar challenges.

Several approaches handle multi-label scenarios:

The multiple-column approach is cleanest but requires training separate models or a model with multiple output heads. Combined tags work for small label sets but explode combinatorially with many types. In practice, most NER systems use flat BIO tagging and handle overlaps through post-processing or by defining a type hierarchy.

Nested Entity Encoding

For nested entities like "New [York [University]]" where "York University" is ORG and "York" is LOC, specialized schemes exist:

This layered approach preserves all entity information but requires models that can predict multiple layers simultaneously. Modern nested NER systems often use span-based prediction instead, directly outputting all valid spans regardless of nesting.

BIO Utilities in Practice

Let's consolidate our functions into a reusable module and demonstrate end-to-end usage with a real NER library.

Integration with spaCy

Real NER systems output entity spans that we can convert to BIO format for analysis or evaluation:

The BIO representation enables token-level evaluation metrics, comparison between different taggers, and training data preparation for sequence models.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

BIO tagging is the dominant approach for sequence labeling, but it has limitations worth understanding.

The fundamental constraint is that standard BIO assumes non-overlapping entities. Each token receives exactly one tag, so nested or overlapping annotations cannot be represented directly. The workarounds we discussed, including multiple layers, combined tags, and separate passes, add complexity and may not suit all applications. For domains with extensive nesting like biomedical text where gene mentions overlap with protein mentions, span-based or graph-based approaches may be more appropriate.

Boundary precision is another challenge. Models often predict the correct entity type but miss exact boundaries. The sentence "the New York Stock Exchange" might be tagged as starting at "New" when it should start at "the New York Stock Exchange" or "New York Stock Exchange" depending on annotation guidelines. BIO's token-level representation means every boundary error affects multiple labels. BIOES mitigates this slightly by making endpoints explicit, but the underlying challenge remains.

Long entities pose particular difficulties for sequence models. An entity spanning ten tokens requires the model to maintain consistent predictions across all ten positions. In BIO, a single mistake, predicting O instead of I in the middle, breaks the entity into two fragments. CRF layers and constrained decoding help by enforcing valid transitions, but very long entities remain error-prone.

Despite these limitations, BIO tagging works well in practice. Its simplicity, universal tooling support, and compatibility with sequence models make it the right choice for most NER applications. Understanding when and why it fails helps you design better systems and interpret results more accurately.

Summary

BIO tagging provides a standardized format for representing entity boundaries in sequence labeling tasks. The key concepts from this chapter:

The BIO scheme uses three prefixes: B (beginning) marks the first token of an entity, I (inside) marks continuation tokens, and O (outside) marks non-entity tokens. This encoding unambiguously represents entity boundaries, handling adjacent same-type entities correctly.

Extended schemes like BIOES add explicit end markers (E) and single-token markers (S) for stronger supervision and easier validation. The choice between BIO and BIOES involves a tradeoff between simplicity and boundary precision.

Conversion utilities transform between span annotations and per-token BIO tags. Robust converters handle edge cases like single-token entities, adjacent entities, and sentence boundaries. Decoders must gracefully handle malformed sequences from model predictions.

Validation and repair catch common errors like orphan I tags and type mismatches. Repair strategies can automatically fix many issues, improving downstream usability.

Multi-label scenarios require extensions like multiple tag columns or layered encoding for nested entities. Standard BIO assumes non-overlapping annotations.

Key Function Parameters

When working with BIO tagging utilities, these parameters control the conversion and validation behavior:

- tokens: List of string tokens representing the input sequence. Must align with span indices for correct conversion.

- spans: List of tuples containing

(start_idx, end_idx, entity_type). Uses Python's exclusive end convention whereend_idxpoints to the position after the last token in the entity. - tags: List of BIO tag strings, one per token. Valid formats include

B-TYPE,I-TYPE, andO. - entity_type: String identifier for the entity category (e.g.,

PER,LOC,ORG). Appears as the suffix in BIO tags after the hyphen.

For BIOES conversion, two additional prefixes are used:

- S-TYPE: Marks single-token entities that don't need B/I/E structure

- E-TYPE: Marks the final token of multi-token entities

The next chapters apply BIO tagging to chunking and introduce the probabilistic models, Hidden Markov Models and Conditional Random Fields, that power production sequence labeling systems.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about BIO tagging for sequence labeling.

Comments