Master Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), the subword tokenization algorithm powering GPT and BERT. Learn how BPE bridges character and word-level approaches through iterative merge operations.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Byte Pair Encoding

In the previous chapter, we explored the vocabulary problem: word-level tokenization struggles with out-of-vocabulary words, rare tokens, and the combinatorial explosion of morphologically rich languages. The solution is to work with smaller units that can be composed to represent any word. But what should these units be?

One option is individual characters. Character-level models have a tiny vocabulary and can represent any string, but they create extremely long sequences and lose the linguistic structure that makes words meaningful. At the other extreme, word-level models preserve semantic units but suffer from vocabulary explosion.

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) finds the sweet spot between these extremes. It starts with characters and iteratively merges the most frequent pairs into new tokens, building a vocabulary of common subword units. The result is a compact vocabulary that can represent any word while preserving meaningful linguistic patterns. BPE powers the tokenizers behind GPT models, RoBERTa, and many other state-of-the-art language models.

In this chapter, we'll understand how BPE works, implement it from scratch, and see how it addresses the challenges we identified earlier.

The Core Insight

BPE originated as a data compression algorithm in the 1990s. The insight is simple: if certain byte sequences appear frequently, replacing them with a single symbol reduces the total size of the data. Applied to text, this means learning which character combinations appear most often and treating them as single units.

A subword tokenization algorithm that iteratively replaces the most frequent pair of consecutive tokens with a new token, building a vocabulary of variable-length subword units from character-level representations.

Consider the word "lowest". A character-level approach produces ['l', 'o', 'w', 'e', 's', 't'], which is six tokens. But if we've seen "low" and "est" frequently in our training data, BPE might encode this as ['low', 'est'], capturing meaningful morphological units in just two tokens.

BPE discovers these patterns automatically from data. You don't need linguistic expertise or hand-crafted rules. Given enough text, BPE learns that "ing", "tion", "pre", and "un" are useful units because they appear frequently and help compress the corpus.

The BPE Algorithm

The BPE algorithm has two phases: training (learning merge rules) and encoding (applying those rules to new text). Let's start with training.

Learning Merge Rules

Training BPE proceeds as follows:

- Initialize the vocabulary with all individual characters plus a special end-of-word token

- Count all adjacent token pairs in the corpus

- Find the most frequent pair and merge it into a new token

- Add a merge rule recording this transformation

- Repeat steps 2-4 until reaching the desired vocabulary size

Each iteration adds one new token to the vocabulary. If you want 10,000 subword tokens and start with 256 characters (bytes), you run 9,744 merge operations.

Let's trace through a small example to see how this works:

We start with each word split into individual characters, with a special </w> marker indicating word boundaries. This marker is crucial: it lets BPE distinguish between "un" at the start of "unhappy" and "un" at the end of "sun".

Now let's count adjacent pairs and find the most frequent one:

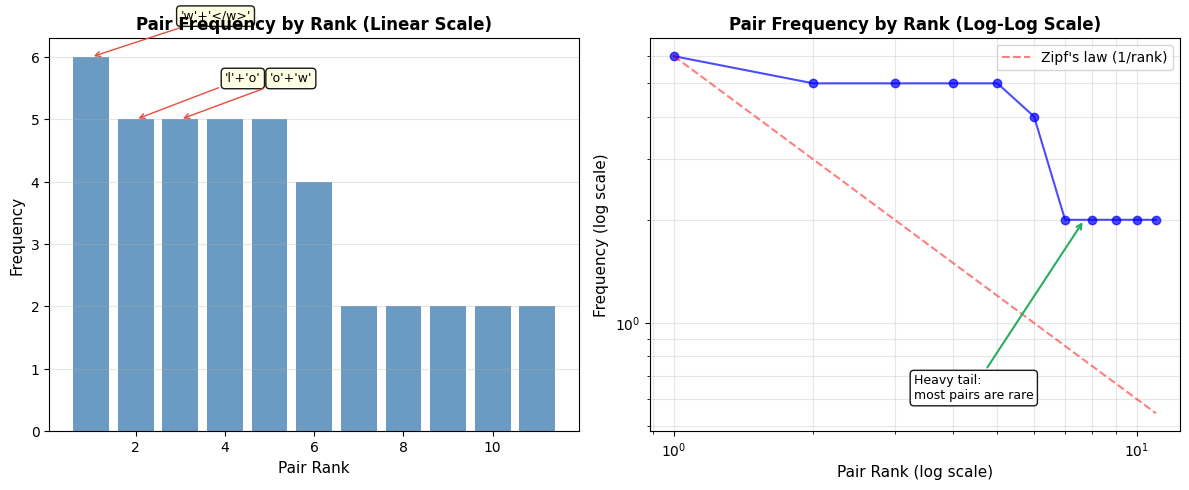

Let's visualize this distribution to see the frequency gap between pairs:

The pair ('e', 'w') appears most frequently (in "new", "newer", "newest"). Let's merge it into a single token:

Notice how "n e w" became "n ew" throughout the vocabulary. The merge is applied everywhere the pair appears. Let's continue for several more iterations to see the vocabulary evolve:

After 10 merges, the algorithm has discovered several meaningful units:

ewfrom words like "new"loandlowfrom words like "low", "lower", "lowest"estas a superlative suffixeras a comparative suffix

These emerge purely from frequency patterns in the data. The algorithm doesn't know English morphology; it simply notices that certain character sequences co-occur frequently.

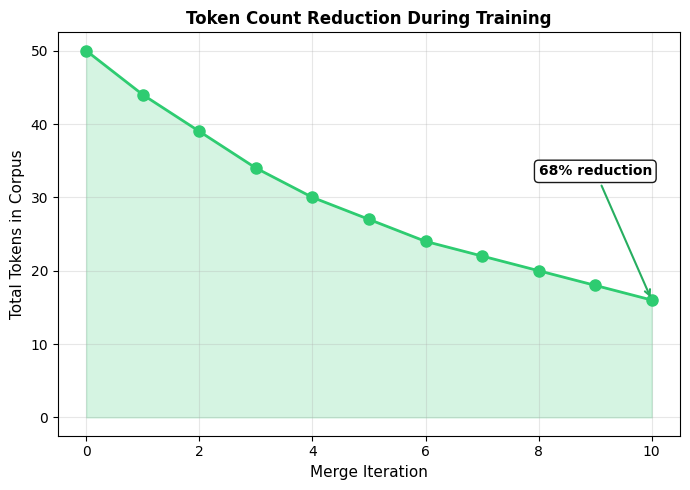

Let's visualize how the pair frequencies are distributed and how token counts decrease as merges are applied:

The left plot shows that pair frequencies follow a Zipf-like distribution: a few pairs dominate while most are rare. This explains why greedy selection works so well. By always choosing the most frequent pair, BPE captures the patterns that matter most for compression.

The right plot shows the payoff: each merge reduces the total token count. Early merges have the biggest impact because they target the most frequent pairs. As training progresses, the remaining pairs are less frequent, so each merge contributes less to compression.

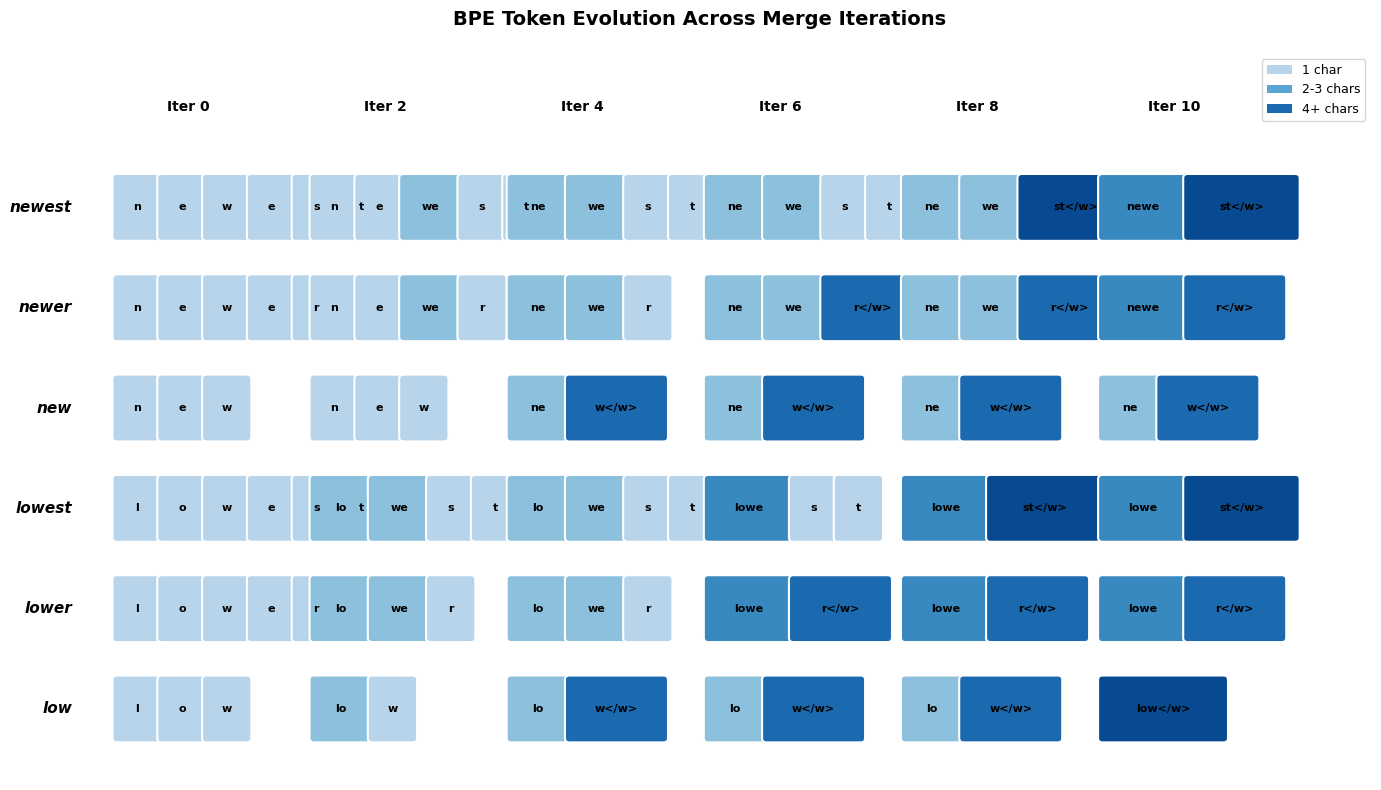

Visualizing the Merge Process

Let's visualize how BPE builds up tokens across iterations:

The visualization shows how BPE progressively builds larger tokens. Initially, each word is a sequence of individual characters. Through merges, common patterns like "ew", "lo", "er", and "est" emerge and get combined into single tokens. By iteration 10, "lowest" is represented as just two tokens: "low" and "est".

Encoding New Text

Once we've learned merge rules, we can encode any new text, including words never seen during training. The encoding algorithm applies merge rules in the order they were learned:

Let's test encoding on both known and unknown words:

Words from training are encoded using the learned merge rules. "low" becomes a single token because the algorithm merged those characters together, while "newest" splits into "new" and "est", reflecting the morphological structure.

BPE handles unknown words gracefully by decomposing them into known subword units. "slower" becomes ['s', 'low', 'er'], correctly identifying the root "low" and comparative suffix "er" even though the full word wasn't in training. "renew" splits into ['r', 'e', 'new'], preserving the common suffix. This is the key advantage over word-level tokenization: BPE can represent any word by falling back to smaller units, ensuring no word ever becomes an unknown token.

Decoding: From Tokens to Text

Decoding is straightforward. Simply concatenate the tokens:

In practice, tokenizers use special markers (like Ġ or ##) to indicate word boundaries, allowing proper spacing when decoding. We'll see this when working with real tokenizers.

Building a Complete BPE Tokenizer

Let's build a more complete BPE tokenizer class that handles the full pipeline:

The tokenizer converts text to both human-readable tokens and numeric IDs. Notice how "running" is split into subword pieces since the full word wasn't common enough in training to get its own token, while frequent words like "the" and "cat" remain intact.

Controlling Vocabulary Size

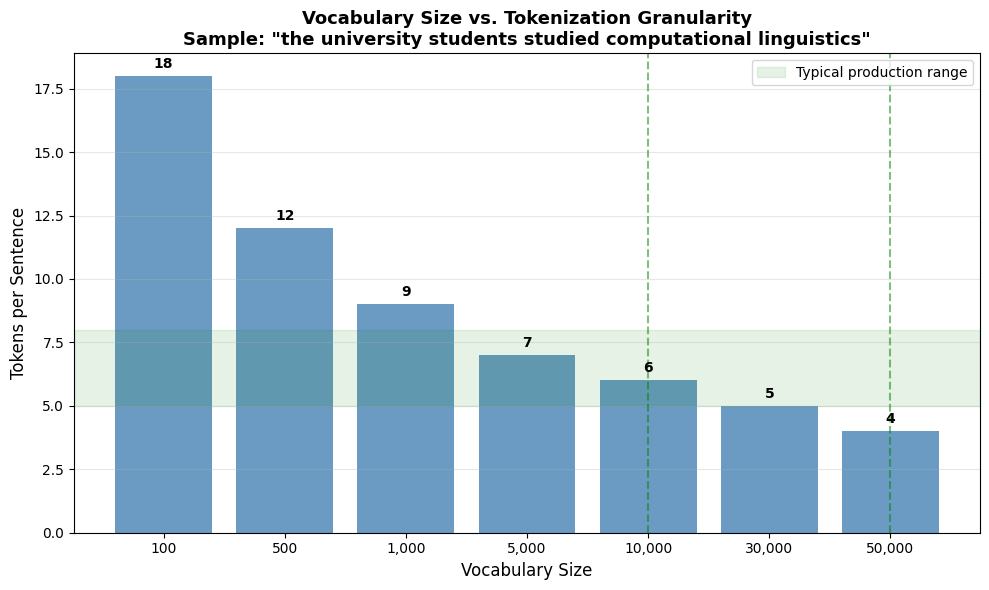

The vocabulary size is BPE's main hyperparameter. It controls the granularity of tokenization:

- Small vocabulary (hundreds of tokens): More character-like, longer sequences, better compression of rare words

- Large vocabulary (tens of thousands): More word-like, shorter sequences, more tokens to learn embeddings for

Let's visualize this tradeoff:

Production models typically use vocabularies between 30,000 and 50,000 tokens:

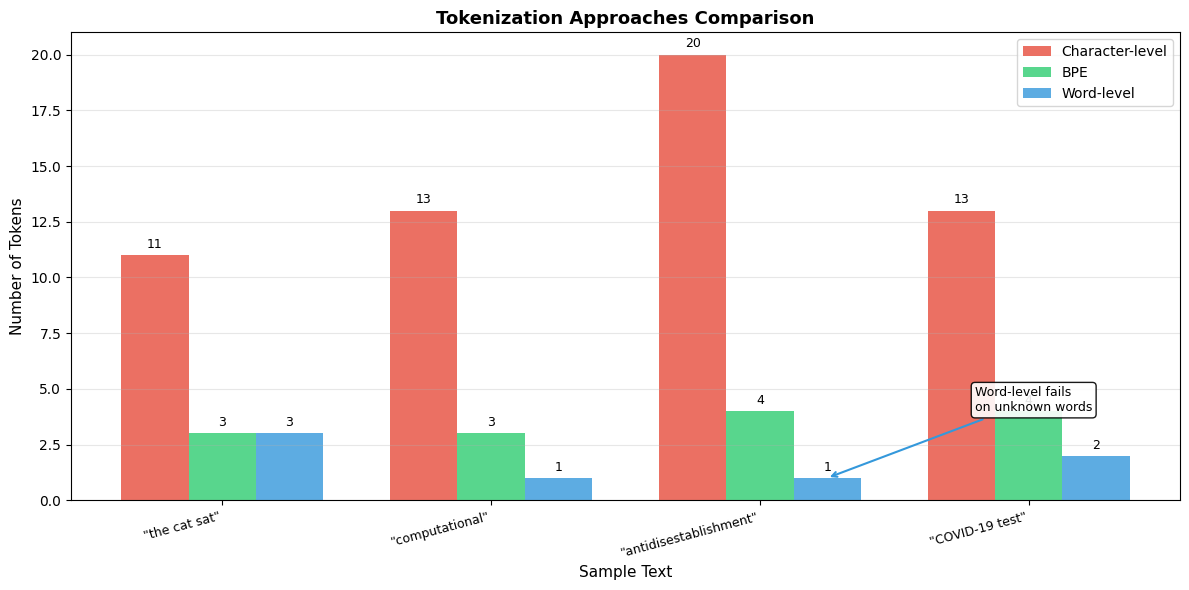

Let's compare how different tokenization strategies handle the same text to see why BPE offers a compelling middle ground:

The comparison shows BPE's advantages clearly. Character-level tokenization creates sequences that are 5-20x longer than necessary. Word-level tokenization fails on novel words like "computational" or "antidisestablishment", mapping them to unknown tokens. BPE balances these tradeoffs: it produces reasonably compact sequences while handling any word through subword decomposition.

Pre-tokenization

Before applying BPE, most implementations pre-tokenize the text. Pre-tokenization splits text into words or word-like units, preventing BPE from merging across word boundaries.

The process of splitting raw text into initial units (typically words) before applying subword tokenization. This prevents merges across word boundaries and often handles whitespace, punctuation, and special characters.

Different models use different pre-tokenization strategies:

Simple whitespace splitting keeps "can't" as a single unit, while GPT-2's regex-based approach separates contractions into their components: "can" and "'t". GPT-2 also preserves leading spaces attached to words (encoded as Ġ in the final vocabulary), allowing the model to distinguish between a word at the start of a sentence versus the middle.

Using Real BPE Tokenizers

In practice, you'll use optimized implementations from the tokenizers library or model-specific tokenizers from Hugging Face. Let's compare our implementation to a production tokenizer:

GPT-2 tokenizes this sentence into around 7-8 tokens. Notice how the tokenizer produces tokens like 'Ġuniversity' where the Ġ character (a special representation of a space) indicates a word boundary. Common words like "The" and "students" remain intact, while less frequent terms like "computational" and "linguistics" may be split into subwords.

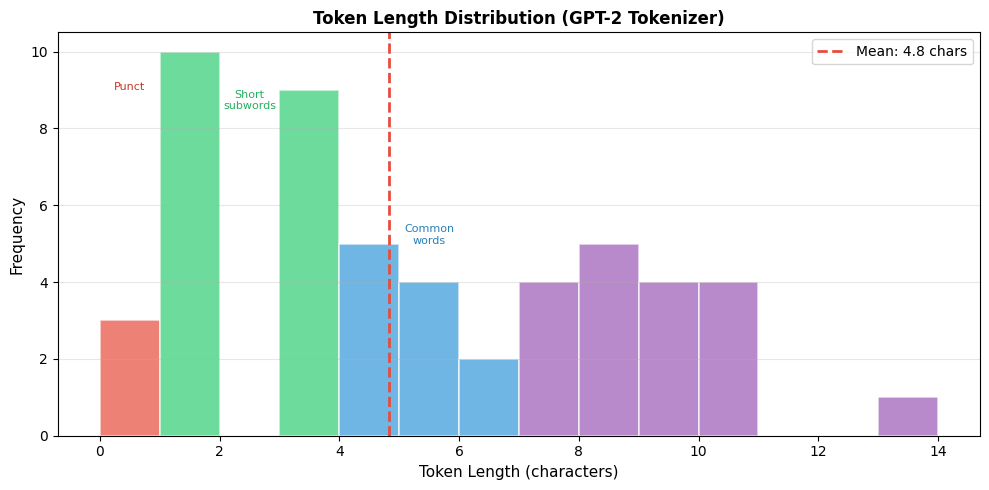

Let's analyze the token length distribution across a sample of English text:

The distribution reveals BPE's subword nature: most tokens are 2-6 characters long, representing common morphemes and short words. Tokens longer than 6 characters are typically complete common words, while single-character tokens often represent punctuation or rare characters.

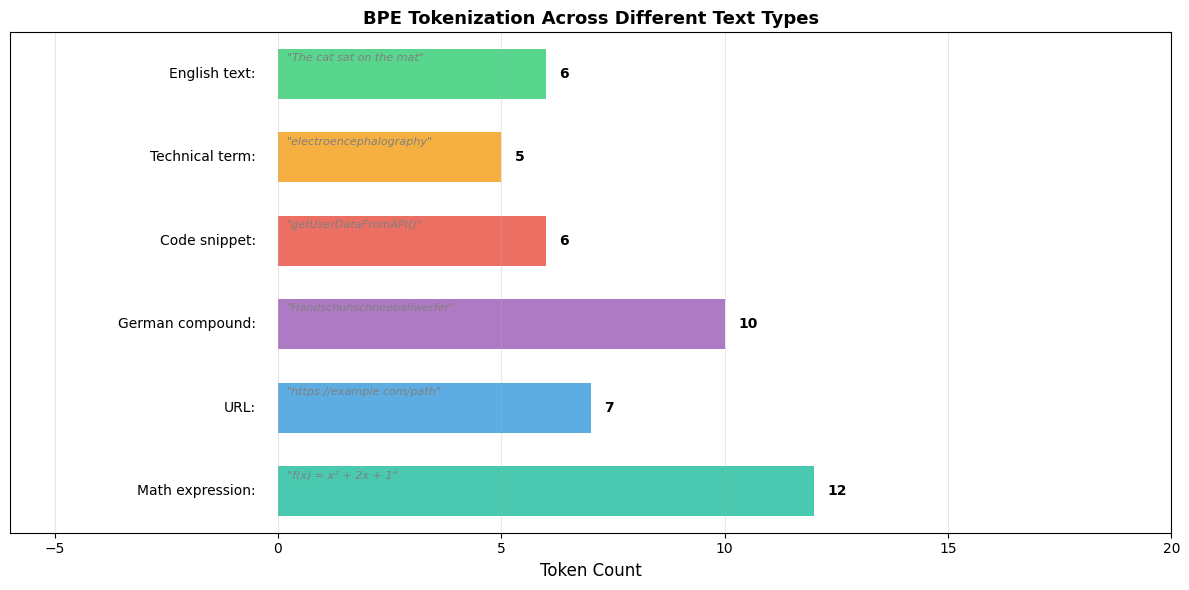

Let's examine how it handles challenging cases:

The tokenizer handles:

- Novel compounds: Breaking "COVID-19" into sensible pieces

- Long words: Decomposing the famously long word into subwords

- Code: Splitting camelCase and snake_case identifiers

- Emojis: Either including them in vocabulary or splitting into bytes

BPE Variations

Several variations of BPE exist, each with different characteristics:

Byte-Level BPE

Standard BPE operates on characters, but byte-level BPE operates directly on UTF-8 bytes. This has a key advantage: the base vocabulary is always exactly 256 tokens (one per byte), regardless of language or script.

ASCII characters like "H" and "e" require just one byte each, while Chinese characters need three bytes and the emoji needs four. Byte-level BPE treats each of these bytes as base tokens, then learns merges on top. This is why GPT-2 and GPT-3 can handle any Unicode text without special preprocessing: the 256-byte base vocabulary covers all possible inputs.

BPE with Dropout

During training, some implementations randomly skip merge rules with a small probability. This creates multiple valid tokenizations for the same word, acting as data augmentation:

With 20% dropout, the same word produces different tokenizations across runs. Some runs apply all merges, producing compact tokenizations, while others skip merges and produce more fragmented outputs. This variation during training acts as regularization, helping models become robust to tokenization differences at inference time.

The Mathematical Perspective

At its core, BPE is a compression algorithm. The goal is simple: represent a corpus using fewer tokens. But why does merging frequent pairs achieve this, and what makes the greedy approach work so well in practice?

From Compression to Tokenization

Consider a corpus represented as a sequence of tokens. Initially, these tokens are individual characters, so a corpus with 1 million characters contains 1 million tokens. Every time we merge two adjacent tokens into one, we reduce the total token count. The question is: which merge gives us the biggest reduction?

Suppose we merge the pair into a new token . Every occurrence of followed by becomes a single token instead of two. If this pair appears 10,000 times in the corpus, we replace 20,000 tokens (10,000 pairs of two) with 10,000 tokens (10,000 single merged tokens), for a net reduction of 10,000 tokens.

This insight leads directly to the BPE merge criterion: choose the pair that appears most frequently, because that merge reduces the token count the most.

The Greedy Merge Formula

Let denote how many times tokens and appear consecutively in the corpus. The optimal merge at each iteration is:

where:

- : the pair selected for merging at this iteration

- : the count of adjacent occurrences of followed by

This formula is simple but effective. We don't need to predict future merges or optimize globally. We simply count pairs, pick the winner, merge it, and repeat. Each merge is locally optimal: it provides the maximum possible reduction in token count given the current vocabulary.

Why Greedy Works

You might wonder: is greedy selection actually optimal? Mathematically, no. There exist contrived examples where a different merge sequence would achieve better compression. However, BPE's greedy approach works well in practice for two reasons:

-

Language has hierarchical structure. Characters form morphemes, morphemes form words, and words form phrases. Frequent character pairs often correspond to meaningful linguistic units. By merging them first, BPE naturally discovers this hierarchy.

-

Local decisions compound well. Merging "e" + "s" into "es" doesn't prevent us from later merging "es" + "t" into "est". The greedy choice at each step creates building blocks for future merges.

The key insight is that pair frequencies in natural language follow a Zipf-like distribution: a few pairs are extremely common, while most pairs are rare. This heavy-tailed distribution means the greedy choice is often dramatically better than alternatives.

The left plot shows the stark difference between top pairs and the rest: the most frequent pair appears far more often than typical pairs. The right plot uses log-log scaling to reveal the Zipf-like distribution. When frequencies follow this pattern, greedy selection captures most of the compression benefit in early iterations.

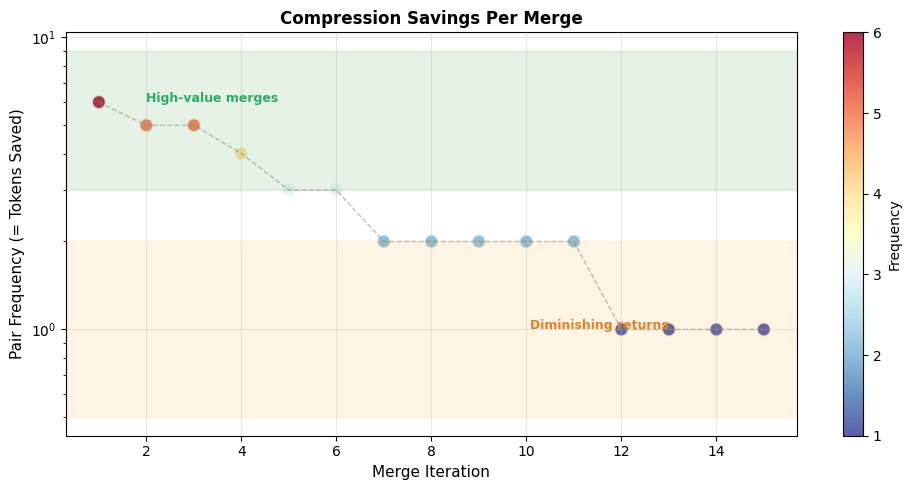

Let's visualize how compression savings relate to pair frequency:

This visualization clearly shows the diminishing returns of BPE merging. Early merges capture pairs that appear many times, yielding large compression gains. As training progresses, we run out of high-frequency pairs and resort to merging less common patterns.

Computational Complexity

BPE's efficiency makes it practical for large corpora. Let be the total number of token occurrences in the corpus and be the number of merge operations. Each iteration requires:

- Counting all adjacent pairs: using a hash table

- Finding the most frequent pair: where is the number of unique pairs

- Applying the merge: in the worst case

With careful implementation using hash tables and priority queues, the total complexity is approximately . For a corpus of 1 billion tokens and 50,000 merges, this remains tractable on modern hardware. Optimized implementations maintain incremental pair counts, avoiding full rescans after each merge.

The practical implication is that BPE training scales well. You can train a production-quality tokenizer on massive web corpora in hours rather than days, which is one reason BPE became the dominant approach for large language models.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite its success, BPE has several limitations:

Tokenization inconsistency: The same substring might be tokenized differently depending on its position within a word. For example, "low" as a standalone word might be a single token, but the same characters within "fellow" might be split as ['fel', 'low']. This positional sensitivity can affect how models process morphologically related words.

Suboptimal for some languages: BPE was designed for alphabetic languages. For logographic scripts like Chinese, where each character already represents a morpheme, character-level tokenization might be more appropriate.

No linguistic knowledge: BPE discovers patterns purely from frequency. It might merge semantically unrelated characters if they happen to co-occur frequently, while splitting meaningful units that are rare.

Training data sensitivity: The learned vocabulary depends heavily on the training corpus. A tokenizer trained on English text will poorly handle French, even if the languages share an alphabet.

Key Parameters

When training or using BPE tokenizers, these parameters have the most significant impact:

| Parameter | Typical Values | Effect |

|---|---|---|

vocab_size | 30,000-50,000 | Controls granularity: smaller vocabularies produce more tokens per word but handle rare words better |

min_frequency | 2-5 | Minimum times a pair must appear to be merged; higher values produce more stable vocabularies |

dropout | 0.0-0.1 | Probability of skipping merge rules during encoding; adds regularization but slows training |

end_of_word_suffix | </w>, Ġ | Marker distinguishing word-final from word-internal subwords |

Vocabulary size is the primary hyperparameter. Production models typically use 30,000-50,000 tokens, balancing compression efficiency against embedding table size. Smaller vocabularies (around 10,000) work well for domain-specific applications where the text is more predictable.

Pre-tokenization strategy significantly affects the learned vocabulary. GPT-2's regex-based pre-tokenization preserves contractions and attaches spaces to tokens, while simpler whitespace splitting may miss these distinctions.

Summary

Byte Pair Encoding solves the vocabulary problem through a simple iterative process. Starting from individual characters, it merges the most frequent adjacent pairs until reaching a target vocabulary size. The result is a set of subword tokens that can represent any word through composition, balancing the vocabulary explosion of word-level tokenization against the long sequences of character-level approaches.

Key takeaways:

- BPE learns merge rules by iteratively combining the most frequent adjacent pairs

- The vocabulary size controls granularity: smaller vocabularies produce more tokens per word but handle rare words better

- Encoding applies merge rules in order, decomposing words into learned subword units

- Unknown words are handled gracefully by falling back to smaller units or individual characters

- Pre-tokenization splits text into words before BPE, preventing cross-word merges

- Byte-level BPE operates on UTF-8 bytes, providing a fixed 256-token base vocabulary for any language

BPE's simplicity and effectiveness have made it the foundation for tokenization in GPT models and many other large language models. In the next chapter, we'll explore WordPiece, a variant that uses a different merging criterion and powers BERT-family models.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding of Byte Pair Encoding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about subword tokenization.

Comments