Master WordPiece tokenization, the algorithm behind BERT that balances vocabulary efficiency with morphological awareness. Learn how likelihood-based merging creates smarter subword units than BPE.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

title: "WordPiece Tokenization" format: html: code-fold: false jupyter: python3

Introduction

WordPiece is a subword tokenization algorithm that powers BERT and many other transformer-based models. While it shares the iterative merge approach with Byte Pair Encoding (BPE), WordPiece makes a subtle but important change: instead of merging the most frequent pairs, it merges pairs that maximize the likelihood of the training data.

This difference matters. BPE's frequency-based criterion treats all pairs equally regardless of context. A pair appearing 100 times in rare words contributes the same as one appearing 100 times in common words. WordPiece's likelihood objective weights pairs by how much they improve the overall model, giving more influence to patterns that appear in frequent contexts.

The result is a tokenization scheme that tends to produce slightly different vocabularies than BPE, often capturing more linguistically meaningful units. You'll recognize WordPiece tokens by their distinctive ## prefix, which marks subword units that continue a word rather than starting one.

Technical Deep Dive

To understand what makes WordPiece different from BPE, we need to think carefully about what it means for a tokenization to be "good." BPE takes a straightforward approach: frequently occurring pairs should become single tokens. But frequency alone misses something important. Consider two pairs that each appear 100 times in a corpus:

- Pair A appears in a very common word that occurs 1,000 times

- Pair B appears in a rare word that occurs only 100 times

Which pair has a stronger "bond"? Pair B seems more tightly associated: whenever that rare word appears, the pair appears too. Pair A's 100 occurrences represent only 10% of its opportunities. WordPiece captures this intuition by asking not "how often does this pair occur?" but "how often does this pair occur relative to what we'd expect by chance?"

This leads us to a likelihood-based formulation that we'll build up step by step.

Building the Likelihood Model

The foundation is a simple probabilistic model of text. We treat the tokenized corpus as a sequence of independent tokens, each drawn from a probability distribution over the vocabulary. This is called a unigram language model. The term "unigram" reflects that each token is modeled independently, without considering its neighbors.

Given a vocabulary and a training corpus tokenized into subword units, the likelihood of the corpus under this model is the product of probabilities for each token:

where:

- : the likelihood of the corpus, indicating how probable the entire tokenized text is under our model

- : the total number of tokens in the tokenized corpus

- : the -th token in the tokenized corpus

- : the probability of token , estimated from the training data

The product arises from the independence assumption: the probability of seeing tokens in sequence equals .

How do we estimate each token's probability? The simplest approach is maximum likelihood estimation: count how often each token appears and divide by the total:

where:

- : the probability assigned to token

- : the number of times token appears in the tokenized corpus

- : the total count of all tokens in the vocabulary , which normalizes the probability

This formula simply says: a token's probability equals its count divided by the total token count, which is the fraction of all tokens that are . If "the" appears 50,000 times in a corpus of 1,000,000 tokens, then .

From Likelihood to Merge Decisions

Now comes the key insight. When we merge a pair into a new token , the likelihood changes. Every occurrence where and appeared adjacent is now represented by a single token instead of two separate tokens. WordPiece selects the merge that maximizes this likelihood increase.

The key question during training is: which pair of adjacent tokens should we merge next? To answer this, we need to compute how much each possible merge would improve the corpus likelihood. WordPiece does this by computing a score for each candidate pair :

where:

- : the merge priority score for the pair, where higher values mean this pair should be merged sooner

- : the number of times tokens and appear adjacent to each other in the corpus

- : the total number of times token appears in the corpus

- : the total number of times token appears in the corpus

This score captures the association strength between tokens and . To build intuition, consider what the denominator represents. If tokens appeared randomly and independently throughout the corpus, how often would we expect to see followed by ? The product gives a baseline expectation. Dividing the actual co-occurrence count by this baseline measures the "surprise" of seeing them together, quantifying how much more often they appear adjacent than random chance would predict.

A high score means and have a strong affinity for each other. They're not just frequent; they're specifically associated. This is exactly what we want in a subword unit.

The WordPiece score is closely related to Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI), a classic measure of association in computational linguistics. PMI measures how much more likely two items appear together compared to if they were independent. The WordPiece score is proportional to the probability ratio that underlies PMI.

Deriving the Score from Likelihood

Let's work through why this score maximizes likelihood. Seeing the derivation helps build deeper understanding.

Step 1: Identify what changes during a merge. When we merge into :

- We remove occurrences of and where they appeared as a pair

- We add occurrences of the new token

- Occurrences of and that weren't adjacent remain unchanged

Step 2: Compute the likelihood ratio. The ratio of the new likelihood to the old likelihood captures the improvement from the merge. For the positions where becomes , the old likelihood contribution was for each occurrence, and the new contribution is . The likelihood ratio for this merge is proportional to:

where:

- : the probability of the new merged token after the merge

- and : the probabilities of the original tokens before merging

- : the number of merge operations (how many times the pair appears)

The exponent appears because each occurrence of the pair contributes independently to the likelihood.

Step 3: Simplify to the score formula. Taking the logarithm converts products to sums and exponents to multiplications, making the expression easier to work with. After simplifying (and noting that the probabilities are proportional to counts), the pair that maximizes the likelihood improvement is the one that maximizes , which is exactly the WordPiece score.

This derivation reveals that WordPiece's merge criterion isn't arbitrary; it emerges directly from the goal of maximizing data likelihood under a unigram model.

The ## Prefix Notation

WordPiece uses a special notation to distinguish word-initial tokens from continuation tokens. Tokens that continue a word (not at the start) are prefixed with ##.

For example, tokenizing "unhappiness":

un ##happi ##ness

This tells us:

unstarts the word##happicontinues from the previous token##nesscontinues from the previous token

The ## prefix serves two purposes:

-

Disambiguation: The token

##ing(word continuation) is different froming(word start). This matters because "ing" at the start of a word (like "ingot") has different distributional properties than "-ing" as a suffix. -

Reconstruction: During decoding, we can easily reconstruct the original text by removing

##prefixes and joining tokens.

The Greedy Tokenization Algorithm

Once we have a trained WordPiece vocabulary, encoding new text follows a greedy longest-match algorithm:

-

For each word in the input: a. Start at the beginning of the word b. Find the longest token in the vocabulary that matches the current position c. Add that token to the output (with

##prefix if not at word start) d. Move past the matched characters e. Repeat until the word is consumed -

If at any point no vocabulary token matches (not even single characters), output the special

[UNK]token for the entire word

This greedy approach is fast but not guaranteed to find the globally optimal tokenization. However, it works well in practice and is computationally efficient.

Handling Unknown Characters

Unlike BPE, which typically includes all individual characters in its base vocabulary, WordPiece implementations often have a fixed character set. When encountering characters outside this set:

- Character-level fallback: Some implementations add unknown characters to the vocabulary during training

- UNK replacement: Others map entire words containing unknown characters to

[UNK] - Normalization: Pre-processing can normalize or remove problematic characters

BERT's WordPiece vocabulary, for instance, was trained primarily on English and has limited coverage of characters from other scripts.

Worked Example

Let's trace through WordPiece training on a small corpus to see how the likelihood-based scoring works.

Consider this training corpus with word frequencies:

"low" (5), "lower" (2), "newest" (6), "widest" (3)

Step 1: Initialization

We start with individual characters (plus the end-of-word marker if used):

Vocabulary: ['d', 'e', 'i', 'l', 'n', 'o', 'r', 's', 't', 'w']

Initial tokenization:

l o w (5)

l o w e r (2)

n e w e s t (6)

w i d e s t (3)

Step 2: Calculate Merge Scores

For each adjacent pair, we calculate the WordPiece score. Recall the formula:

where is how often and appear adjacent, and , are the total occurrences of each token. Let's compute some scores:

-

Pair

(e, s): appears in "newest" (6) and "widest" (3) = 9 times- count(e) = 2 + 6 + 3 = 11 (in "lower", "newest", "widest")

- count(s) = 6 + 3 = 9

- score = 9 / (11 × 9) = 0.091

-

Pair

(s, t): appears in "newest" (6) and "widest" (3) = 9 times- count(s) = 9

- count(t) = 6 + 3 = 9

- score = 9 / (9 × 9) = 0.111

-

Pair

(l, o): appears in "low" (5) and "lower" (2) = 7 times- count(l) = 5 + 2 = 7

- count(o) = 5 + 2 = 7

- score = 7 / (7 × 7) = 0.143

The pair (l, o) has the highest score, so we merge it first.

Step 3: After First Merge

Vocabulary: ['d', 'e', 'i', 'l', 'lo', 'n', 'o', 'r', 's', 't', 'w']

Updated tokenization:

lo w (5)

lo w e r (2)

n e w e s t (6)

w i d e s t (3)

We continue this process until reaching our target vocabulary size.

Contrast with BPE

With pure frequency counting (BPE), we might merge (e, s) or (s, t) first since they each appear 9 times, compared to (l, o)'s 7 times. The likelihood-based score adjusts for the base frequencies of each token, preferring pairs where the co-occurrence is more "surprising" given the individual token frequencies.

Code Implementation

Let's implement WordPiece from scratch to understand the algorithm deeply. We'll build a simplified version that captures the core concepts.

First, we set up our basic data structures and the scoring function:

Now let's add the scoring and merge selection logic:

Finally, let's add the training loop:

Let's test our implementation:

The trained vocabulary contains 20 tokens, including both word-initial characters and merged subword units. Notice how the algorithm has learned tokens like "lo" (from "low"/"lower"), "est" (from "newest"/"widest"), and other common patterns from our corpus.

Now let's test how the trained tokenizer handles various words, including some it hasn't seen before:

The tokenizer successfully handles both training words and novel words like "lowest" and "newer". Words from training ("low", "lower", "newest", "widest") tokenize efficiently using learned subwords. Novel words are decomposed into known subword units. For example, "lowest" uses the learned "lo" and "est" patterns, while "newer" combines "n", "e", "w", "e", "r" since these character-level tokens are in the vocabulary.

Using Hugging Face Tokenizers

In practice, you'll use optimized implementations like the Hugging Face tokenizers library. Let's see how to train and use a WordPiece tokenizer:

With a vocabulary of 100 tokens trained on our small corpus, the tokenizer has learned common words and subword patterns. Let's test it on some example sentences:

Common words like "machine" and "learning" that appeared frequently in training are kept as whole tokens, while less common words like "transformational" are split into subword units. The ## prefix on continuation tokens allows perfect reconstruction of the original text.

The Hugging Face tokenizer provides a production-ready implementation with special token handling, efficient encoding, and seamless integration with transformer models.

Comparing WordPiece and BPE

The table below compares how WordPiece and BPE tokenize the same words. Notice the key differences: WordPiece uses the ## prefix to mark continuation tokens, while BPE treats all tokens uniformly. WordPiece also tends to find more morphologically meaningful boundaries.

##prefix to indicate continuation tokens, making word boundaries explicit.| Word | WordPiece Tokens | BPE Tokens |

|---|---|---|

| playing | play ##ing | play ing |

| unhappiness | un ##happy ##ness | un happ iness |

| internationalization | inter ##nation ##al ##ization | inter national ization |

| transformer | transform ##er | trans former |

| embedding | embed ##ding | emb ed ding |

The likelihood-based scoring in WordPiece produces different token boundaries than BPE's frequency-based approach. For example, WordPiece keeps "transform" intact as a meaningful unit, while BPE splits it into "trans" and "former". Similarly, WordPiece identifies "happy" as a complete morpheme, while BPE produces "happ" which is less linguistically meaningful.

WordPiece in BERT

WordPiece became famous as the tokenization algorithm behind BERT. Understanding how BERT uses WordPiece helps explain its practical impact.

BERT's Vocabulary

BERT's original English model uses a 30,522 token vocabulary trained on Wikipedia and BookCorpus. The vocabulary includes:

- Special tokens:

[PAD],[UNK],[CLS],[SEP],[MASK] - Word-initial tokens: Complete words and word prefixes without

## - Continuation tokens: Subword units prefixed with

##

Let's examine how this vocabulary is structured by counting the different token types:

The vocabulary splits roughly evenly between word-initial tokens and continuation tokens. This balance allows BERT to represent common words as single tokens while still handling rare or complex words through subword decomposition.

Tokenization in Action

Let's see how BERT tokenizes various text examples:

Common words like "hello", "world", and "machine" appear as single tokens because they're frequent enough to have their own vocabulary entries. More complex words get decomposed: "revolutionized" splits into "revolution" + "##ized", preserving the morphological structure. The extremely long word "antidisestablishmentarianism" is broken into many subword pieces, but each piece is a meaningful unit that BERT has learned during pre-training.

Handling Special Cases

WordPiece in BERT includes several practical handling mechanisms:

The tokenizer handles accented Latin characters ("café", "naïve") by decomposing them into base characters and accent marks. Numbers and punctuation are also tokenized character-by-character. Chinese characters may produce [UNK] tokens in the English-only BERT model since they weren't in the training vocabulary.

BERT's vocabulary was primarily trained on English text, so it has limited coverage of non-Latin scripts. Multilingual BERT (mBERT) addresses this with a larger vocabulary trained on 104 languages.

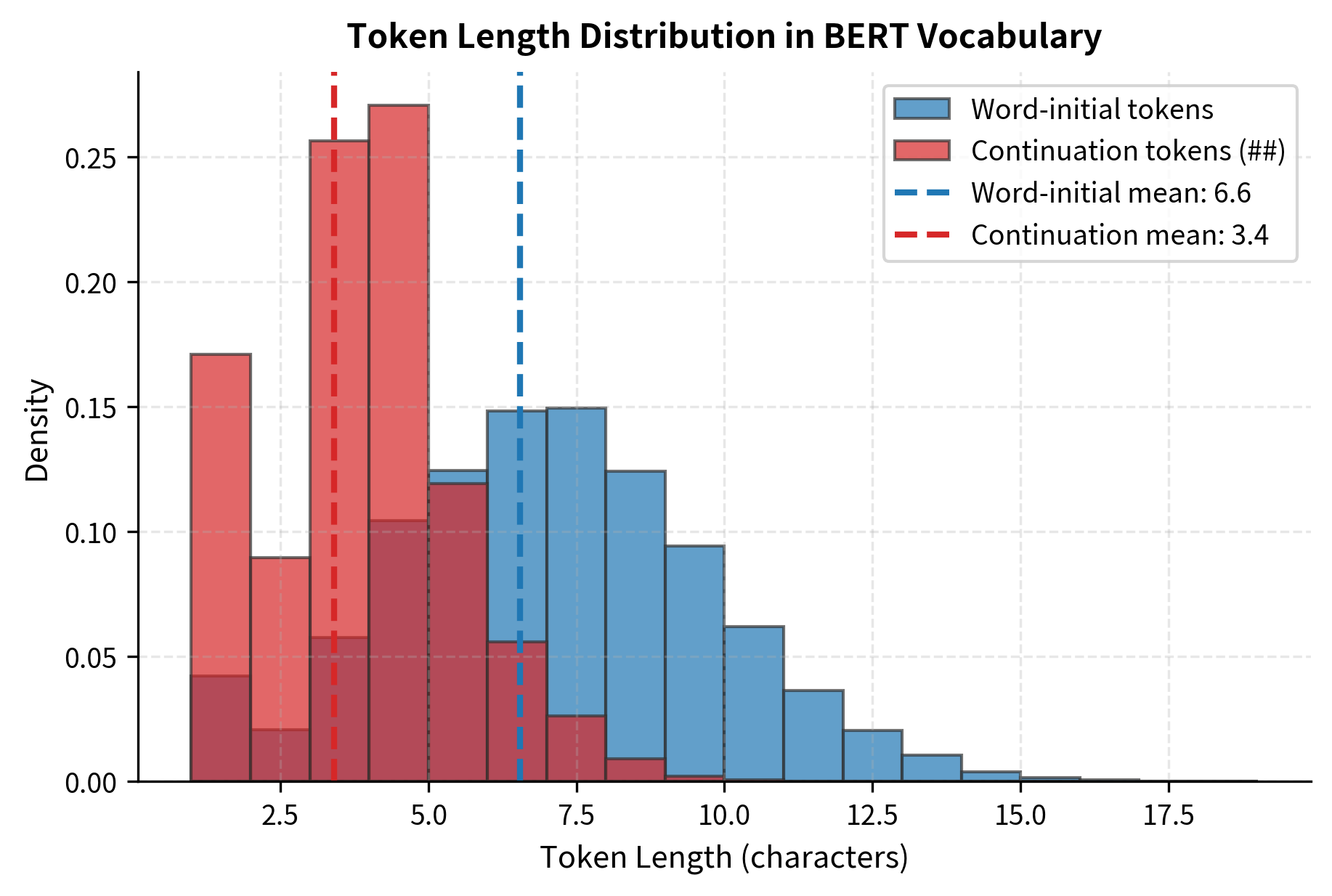

Visualization: Token Length Distribution

The token length distribution reveals interesting patterns. Continuation tokens (##) tend to be shorter on average because they capture common suffixes like "##ing", "##ed", "##ly". Word-initial tokens include both short function words and longer content words.

Key Parameters

The main parameters for WordPiece tokenization are:

-

vocab_size: The target vocabulary size after training. This controls the trade-off between token granularity and model complexity. BERT uses 30,522 tokens; GPT-2 uses 50,257. Larger vocabularies mean more words are represented as single tokens (reducing sequence lengths), but increase embedding table size. For English-only models, 30,000-50,000 works well. Multilingual models typically use 100,000+ tokens to cover multiple scripts.

-

min_frequency: Minimum occurrence count for a character pair to be considered for merging during training. Setting this to 2-5 filters out rare patterns that might represent noise. Higher values (5-10) create cleaner vocabularies but may miss useful domain-specific patterns. Lower values (1-2) capture more subword patterns at the risk of overfitting to training corpus idiosyncrasies.

-

unk_token: The token used to represent out-of-vocabulary characters or words (typically

[UNK]). Unlike BPE, which can always fall back to bytes, WordPiece may produce[UNK]tokens for characters not in its vocabulary. This is more common when using a vocabulary trained on a different language or domain. -

special_tokens: Reserved tokens with specific roles in the model. Common choices include

[CLS](classification),[SEP](separator),[PAD](padding),[MASK](masked language modeling), and[UNK](unknown). These are added to the vocabulary before training and excluded from the merge process. Design these based on your model's downstream tasks.

Limitations and Impact

Limitations

WordPiece shares some limitations with BPE:

-

Context-independent tokenization: The same word always tokenizes the same way regardless of context. "Lead" (the metal) and "lead" (to guide) produce identical tokens, losing the semantic distinction.

-

Suboptimal for non-Latin scripts: Vocabularies trained primarily on English have poor coverage of other writing systems. Characters from unsupported scripts often become

[UNK]tokens. -

Greedy encoding: The longest-match encoding algorithm doesn't guarantee globally optimal tokenization. Alternative segmentations might better capture the intended meaning.

-

Fixed vocabulary: Once trained, the vocabulary can't adapt to new domains without retraining. A model trained on news may struggle with medical text that uses unfamiliar terminology.

Impact

Despite these limitations, WordPiece has been influential:

-

Enabled BERT's success: The combination of WordPiece tokenization with masked language modeling created one of the most impactful NLP models. BERT's tokenization approach became a template for subsequent models.

-

Balanced coverage and efficiency: WordPiece's likelihood-based merging creates vocabularies that handle both common and rare words effectively, finding a practical balance between vocabulary size and coverage.

-

Established subword conventions: The

##prefix notation became widely adopted, providing a clear standard for distinguishing word-initial from continuation tokens. -

Inspired improvements: Later algorithms like SentencePiece and Unigram Language Model tokenization built on WordPiece's foundations while addressing some limitations.

Summary

WordPiece tokenization differs from BPE in one crucial way: it selects merges based on likelihood improvement rather than raw frequency. This means pairs that occur more often than expected given their individual frequencies get priority, leading to vocabularies that better capture meaningful subword patterns.

You now understand the key elements of WordPiece:

- The likelihood-based scoring formula: , which measures the association strength between adjacent tokens

- The

##prefix notation that distinguishes word-initial from continuation tokens - The greedy longest-match encoding algorithm

- How BERT applies WordPiece in practice

WordPiece remains a foundational technique in modern NLP, powering BERT and its many variants. While newer tokenization methods have emerged, understanding WordPiece provides essential context for working with transformer models and designing tokenization pipelines.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding of WordPiece tokenization? Take this quiz to reinforce the key concepts.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding of WordPiece tokenization? Take this quiz to reinforce the key concepts behind BERT's subword algorithm.

Comments