Learn how special tokens like [CLS], [SEP], [PAD], and [MASK] structure transformer inputs. Understand token type IDs, attention masks, and custom tokens.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Special Tokens

Introduction

Special tokens are the invisible orchestrators of modern language models. While subword tokenization handles the vocabulary problem for regular words, special tokens serve a fundamentally different purpose: they provide structural signals that guide how models process, understand, and generate text. These tokens do not represent words or subwords from the training corpus. Instead, they carry meta-information about sequence boundaries, padding, masking, and task-specific markers.

When you feed text into BERT, GPT, or any transformer-based model, the tokenizer doesn't just convert words to numbers. It wraps your input in a scaffold of special tokens. The [CLS] token tells BERT where to look for a sentence-level representation. The [SEP] token marks boundaries between segments. The [PAD] token fills sequences to uniform length. Without these structural markers, transformers would struggle to know where sentences begin, where they end, and which parts to attend to.

This chapter explores the taxonomy of special tokens, their roles in different architectures, and how to work with them effectively. You'll learn not just what each token does, but why it exists and how its design reflects the underlying model's training objectives.

Technical Deep Dive

To understand special tokens, we must first recognize a fundamental problem: transformer models operate on sequences of embeddings, but they have no inherent understanding of where a sentence begins, ends, or how multiple sentences relate to each other. Raw token sequences carry content but lack structure. Special tokens solve this by embedding structural information directly into the input. They are reserved vocabulary positions that carry meta-information rather than linguistic content.

Unlike subword tokens that emerge organically from frequency-based algorithms like BPE or WordPiece, special tokens are manually defined before training begins. They occupy fixed positions in the vocabulary (typically at the very beginning) and are never merged or split during tokenization. This deliberate design ensures they retain their intended structural meaning throughout training and inference.

The Core Special Tokens

Modern language models share a common vocabulary of structural markers, though the exact symbols vary between architectures. Let's examine each one, understanding not just what it does, but why it's needed.

The Classification Token [CLS]

Consider the challenge of sequence classification. You have a sentence like "I loved this movie!" and need a single vector representation to feed into a classifier. But transformers produce one embedding per token. Where should you look for the "meaning" of the whole sentence?

A special token prepended to every input sequence. The hidden state corresponding to this token is used as the aggregate sequence representation for classification tasks. During pre-training, the model learns to encode sentence-level information into this position.

The [CLS] token provides a dedicated aggregation point. Because self-attention allows every token to attend to every other token, information from the entire sequence flows into the [CLS] position. By the final layer, the [CLS] embedding has "seen" the whole sentence and can represent its overall meaning. This is more principled than alternatives like averaging all token embeddings, because the model learns during pre-training exactly what information to aggregate.

The Separator Token [SEP]

Many NLP tasks involve comparing two pieces of text: question answering (question + context), natural language inference (premise + hypothesis), or semantic similarity (sentence A + sentence B). How does the model know where one ends and the other begins?

Marks boundaries between segments in multi-segment inputs. For tasks like question answering or natural language inference, the input contains two distinct text segments. The [SEP] token tells the model where one segment ends and another begins.

The [SEP] token acts as a visible boundary marker. When the model sees [CLS] question tokens [SEP] context tokens [SEP], it can learn that tokens before the first [SEP] are the question and tokens after are the context. This explicit boundary enables the model to learn different attention patterns for cross-segment reasoning.

The Padding Token [PAD]

GPU computation is most efficient when processing batches of sequences simultaneously. But what if your batch contains sentences of different lengths? You can't have a jagged tensor: all sequences must have the same length.

Fills sequences to a uniform length within a batch. Since transformers process batches of sequences in parallel, all sequences must have the same length. Shorter sequences are padded, and attention masks ensure the model ignores these padding positions.

The [PAD] token fills shorter sequences to match the longest one in the batch. But padding introduces a problem: we don't want the model to attend to these meaningless positions. This is where attention masks become essential (we'll explore this mechanism shortly).

The Mask Token [MASK]

How do you train a language model without labeled data? BERT's innovation was masked language modeling: hide some words and train the model to predict them from context. But you need a placeholder for the hidden words.

Used exclusively during masked language modeling pre-training. A percentage of input tokens are replaced with [MASK], and the model learns to predict the original tokens. This creates a self-supervised learning signal without requiring labeled data.

The [MASK] token signals "predict what goes here." During pre-training, about 15% of tokens are replaced with [MASK], and the model's objective is to reconstruct the original vocabulary item. This forces the model to build rich contextual representations, since it must understand the surrounding context deeply enough to infer the missing word.

The Unknown Token [UNK]

What happens when the tokenizer encounters something it cannot represent? While subword tokenization can theoretically decompose any string into known pieces, edge cases exist.

A fallback for tokens that cannot be represented by the vocabulary. While subword tokenization can theoretically handle any input by breaking it into smaller pieces, some tokenizers may encounter truly unknown characters or sequences.

The [UNK] token is a fallback for characters or sequences the tokenizer cannot handle. Modern byte-level tokenizers rarely need it, but it remains a safety net.

Input Formats Across Architectures

Different model architectures use special tokens in characteristic patterns. Understanding these patterns helps you correctly format inputs for any model.

Encoder-only models (BERT, RoBERTa, ALBERT)

These models process text bidirectionally, attending to both past and future tokens. Their input format follows a strict template:

For single-segment tasks (like sentiment classification):

For two-segment tasks (like question answering):

The [CLS] always appears first, providing the aggregation point. Each segment ends with [SEP]. This consistent structure allows the model to learn reliable positional expectations during pre-training.

Decoder-only models (GPT-2, GPT-3, LLaMA)

Autoregressive models generate text left-to-right and need different markers. They typically use:

- Beginning-of-sequence (BOS): Signals the start of generation

- End-of-sequence (EOS): Signals when to stop generating

The naming varies across implementations:

| Model | BOS Token | EOS Token |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-2 | <|endoftext|> | <|endoftext|> |

| LLaMA | <s> | </s> |

| Generic | <bos> | <eos> |

GPT-2's use of the same token for both beginning and end reflects its design: text documents are simply concatenated with <|endoftext|> between them during training.

Encoder-decoder models (T5, BART)

These models combine conventions: the encoder uses separator-style tokens, while the decoder uses beginning/end tokens. T5 introduces additional sentinel tokens (<extra_id_0>, <extra_id_1>, etc.) for its span corruption pre-training objective.

Token Type IDs: Distinguishing Segments

Knowing where segments end (via [SEP]) isn't enough. The model also needs to know which segment each token belongs to. Token type IDs (also called segment IDs) provide this information explicitly.

Consider processing "The cat sat." and "A dog barked." as a sentence pair:

Tokens: [CLS] The cat sat . [SEP] A dog barked . [SEP]

Token Type IDs: 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1

The pattern is straightforward:

where:

- All tokens in segment 1 (including

[CLS]and the first[SEP]) receive type ID 0 - All tokens in segment 2 (including the final

[SEP]) receive type ID 1

These IDs are converted to learned embeddings, giving the model explicit information about segment membership. This allows the model to learn different behaviors for tokens depending on which segment they belong to, which matters for tasks like determining if one sentence entails another.

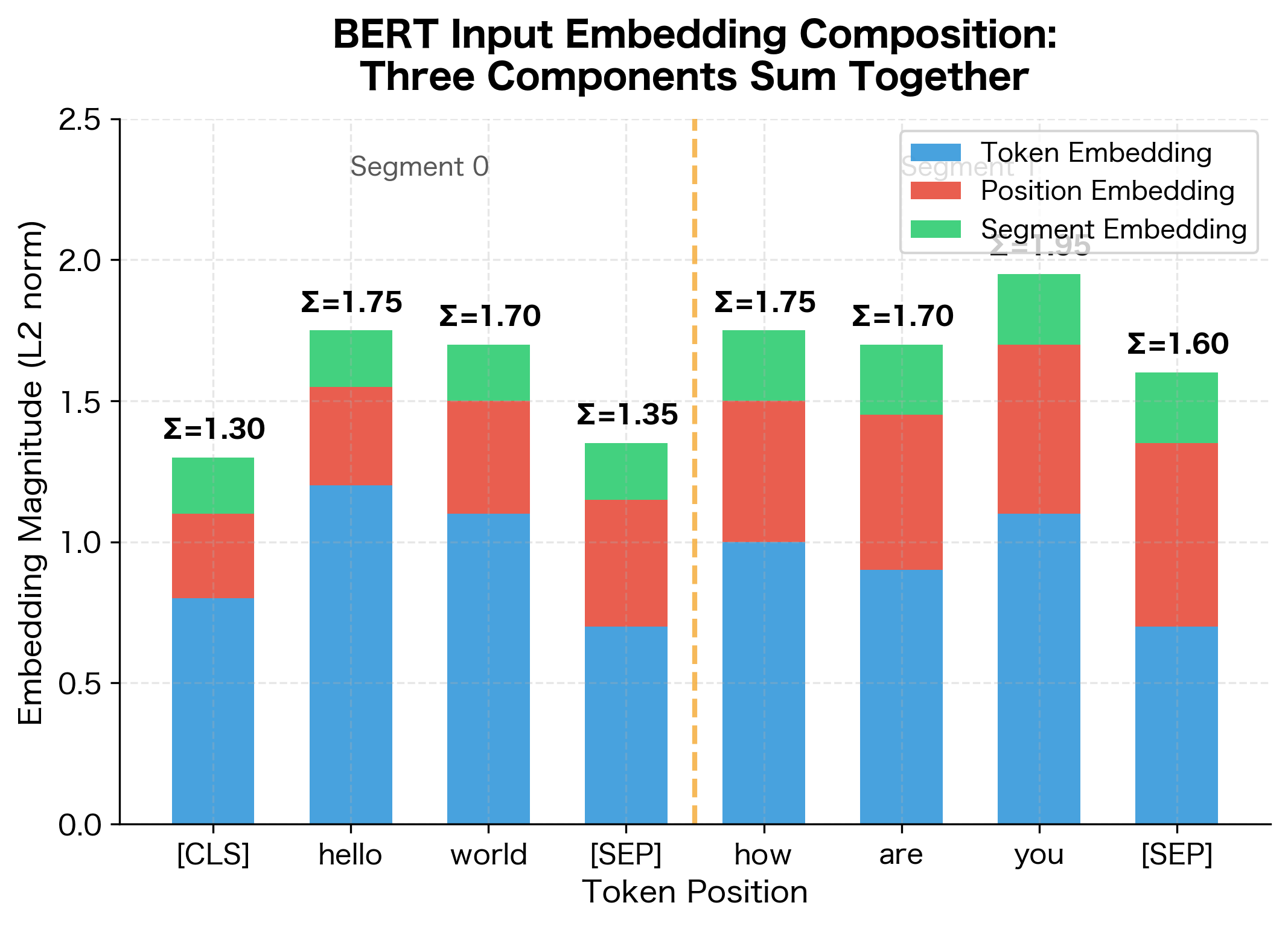

The Complete Input Embedding

With all the pieces in place, we can now understand how a token's position, identity, and segment membership combine into a single representation. For each position in the input sequence, the model computes a total embedding by summing three components:

where:

- : the embedding for token , looked up from the vocabulary embedding table. This captures the token's semantic meaning.

- : the positional embedding for position . This encodes where the token appears in the sequence.

- : the segment embedding for the token type at position . This distinguishes which segment the token belongs to.

All three embedding tables are learned during pre-training. The additive combination allows each type of information to influence the representation while keeping the model architecture simple.

The visualization shows how each token's input representation combines three distinct signals. Token embeddings (blue) carry semantic meaning and vary based on what word appears at each position. Position embeddings (red) encode sequential order, gradually increasing as we move through the sequence. Segment embeddings (green) distinguish the two segments, with a visible boundary at position 4 where the second segment begins.

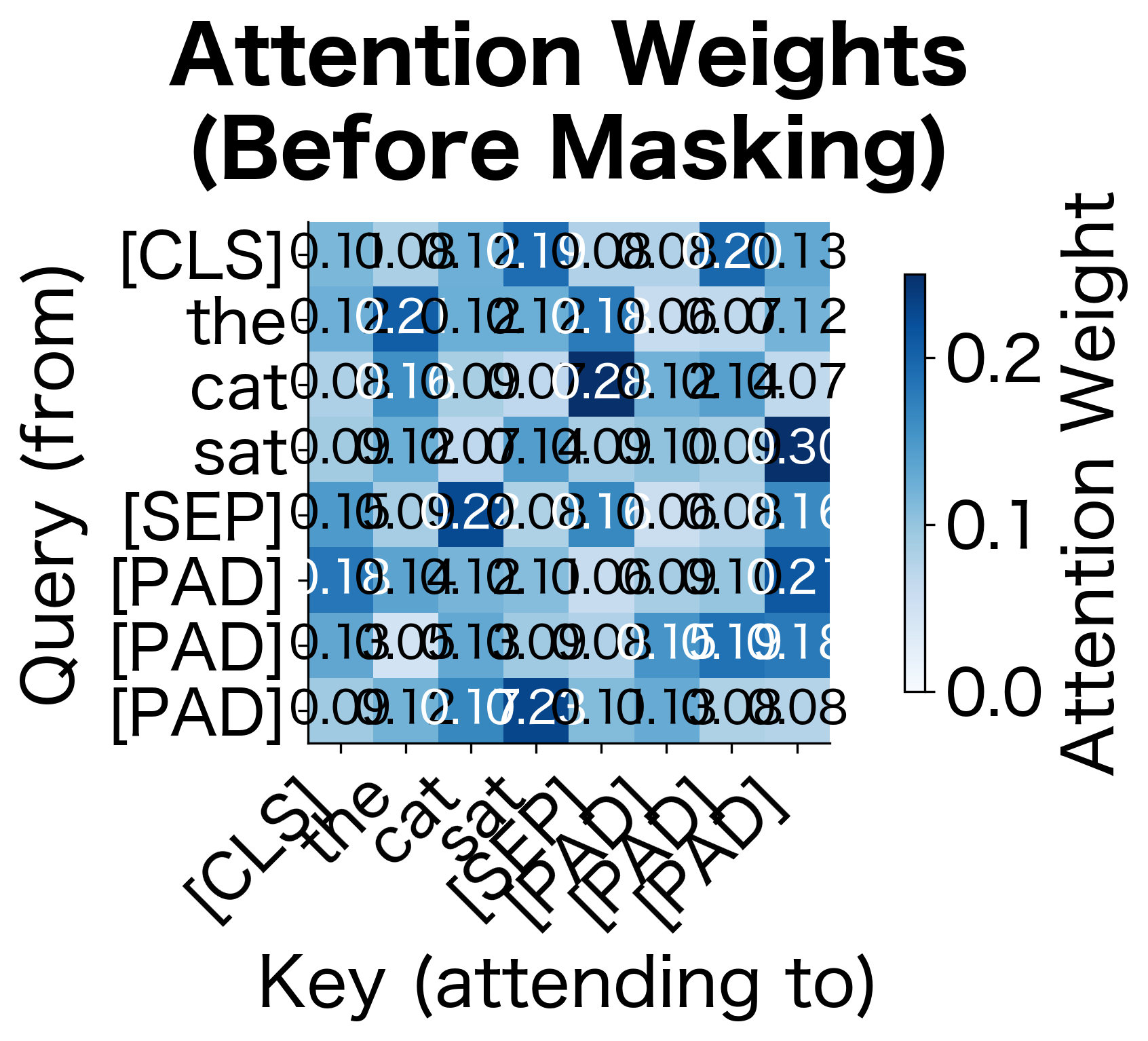

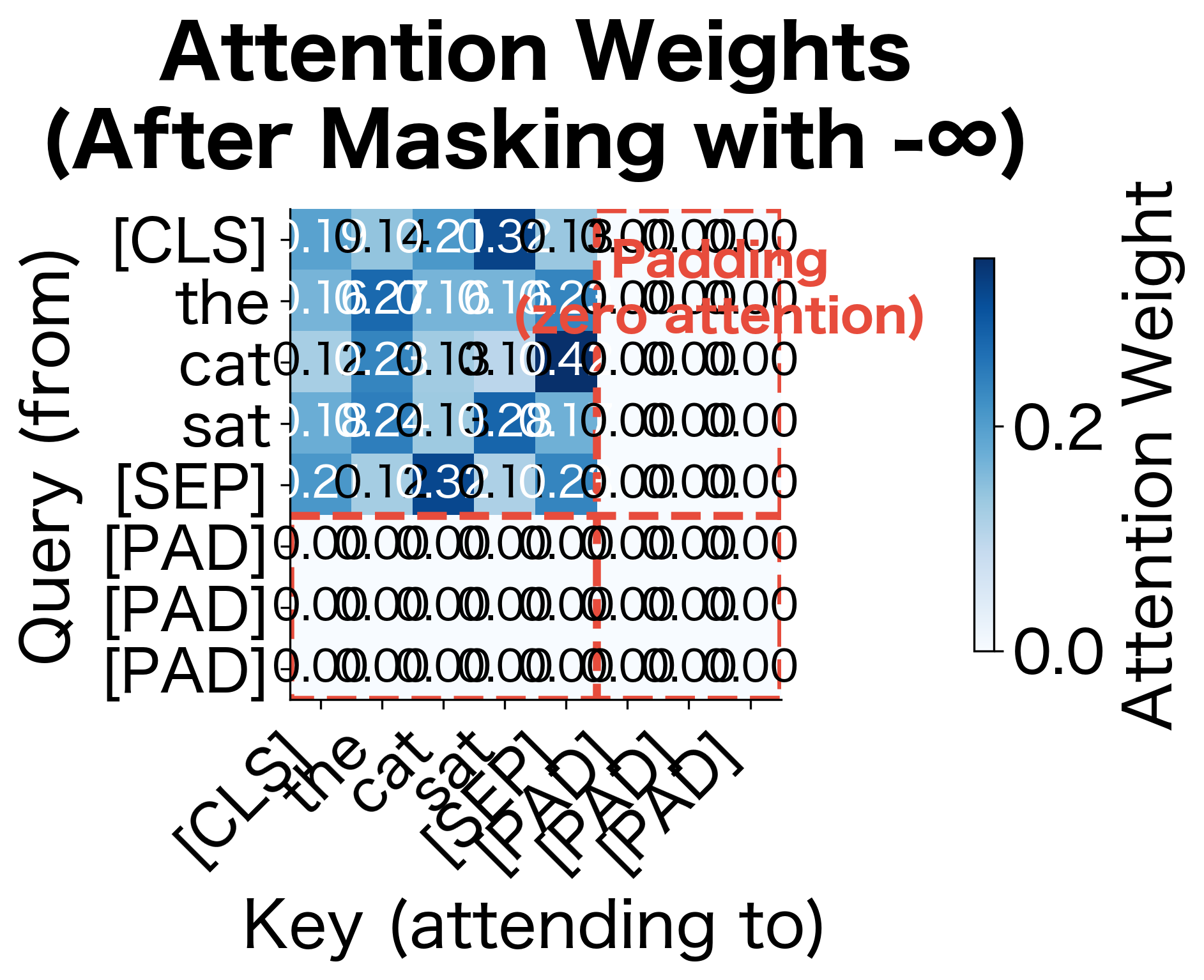

Attention Masks: Neutralizing Padding

Padding solves the variable-length problem but creates a new one: how do we prevent the model from attending to these meaningless positions? The answer is the attention mask, a binary vector that marks which tokens are real:

where:

- 1 indicates a real token that should participate in attention

- 0 indicates padding that should be ignored

The mechanism works by modifying the attention computation. Recall that self-attention computes a weighted combination of values based on query-key compatibility. Before applying softmax to the attention scores, we add a mask matrix :

where:

- , , are the query, key, and value matrices

- is the key dimension (for scaling stability)

- is the mask matrix with values of for real tokens and for padding

Why negative infinity? When you add to an attention score and then apply softmax, the exponential of negative infinity is zero:

This mathematically eliminates padding positions from the attention computation. Real tokens never "see" padding, ensuring that representations are computed purely from meaningful content.

The heatmaps demonstrate the masking mechanism. Before masking (left), attention is distributed across all positions including padding. After adding to padding positions and applying softmax (right), those columns and rows become exactly zero. Real tokens only attend to other real tokens, while padding positions are completely isolated from the computation.

A Worked Example

Now that we understand the theory, let's trace through the complete tokenization process step by step. We'll see exactly how special tokens, token type IDs, and attention masks come together to create a properly formatted input.

Single-Segment Example: Sentiment Classification

Consider classifying the sentiment of: "I loved this movie!"

Step 1: Subword Tokenization

First, the text is converted to subword tokens using the model's vocabulary:

["i", "loved", "this", "movie", "!"]

At this point, we have content tokens but no structure. The model wouldn't know where the sentence starts or ends.

Step 2: Adding Special Tokens

The tokenizer wraps the sequence with structural markers:

["[CLS]", "i", "loved", "this", "movie", "!", "[SEP]"]

Now the model has:

- A dedicated position (

[CLS]) for aggregating sequence-level meaning - A clear boundary marker (

[SEP]) indicating the sequence is complete

Step 3: Converting to IDs

Each token is mapped to its vocabulary ID. Special tokens occupy fixed positions at the start of the vocabulary:

[101, 1045, 2866, 2023, 3185, 999, 102]

Here, 101 is always [CLS] and 102 is always [SEP] in BERT's vocabulary. These fixed IDs ensure consistent behavior across all inputs.

Step 4: Creating Auxiliary Tensors

The tokenizer generates two additional tensors that guide the model's attention:

| Tensor | Values | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Attention mask | [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1] | All positions contain real tokens |

| Token type IDs | [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0] | Single segment (all zeros) |

With no padding needed, the attention mask is all ones. With only one segment, all token type IDs are zero.

Two-Segment Example: Natural Language Inference

Now consider a more complex case. Natural language inference requires comparing two sentences:

- Premise: "The cat sat on the mat."

- Hypothesis: "A feline was resting."

The model must determine their relationship (entailment, contradiction, or neutral).

Step 1-2: Tokenization with Special Tokens

Both segments are tokenized and joined with appropriate markers:

["[CLS]", "the", "cat", "sat", "on", "the", "mat", ".", "[SEP]",

"a", "fe", "##line", "was", "resting", ".", "[SEP]"]

Notice several things:

[CLS]starts the entire input- The first

[SEP]separates premise from hypothesis - The second

[SEP]marks the end of the hypothesis - "feline" is split into

["fe", "##line"]by WordPiece (the##indicates continuation)

Step 3: Token Type IDs

This is where segment distinction matters:

Position: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Token: [CLS] the cat sat on the mat . [SEP] a fe ##line was resting . [SEP]

Token Type: 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1

The first 9 positions (premise including its [SEP]) have type 0. The remaining positions (hypothesis) have type 1. This explicit segmentation enables the model to learn different reasoning patterns for cross-segment comparison.

Step 4: Attention Mask

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1]

All tokens are real, so all positions get attention weight 1.

Adding Padding

What if we're batching multiple inputs of different lengths? Consider adding a shorter sentence to our batch:

- Input 1: "The cat sat on the mat." + "A feline was resting." (16 tokens)

- Input 2: "Hello world!" (5 tokens after adding

[CLS]and[SEP])

To process these together, Input 2 must be padded to length 16:

Input 2 tokens: ["[CLS]", "hello", "world", "!", "[SEP]", "[PAD]", "[PAD]", ... "[PAD]"]

Attention mask: [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

The attention mask now contains zeros for padding positions, telling the model to ignore them during attention computation. Without this mask, the model would attend to padding and produce corrupted representations.

Code Implementation

Having understood the theory and traced through examples by hand, let's now implement and explore special tokens using the Hugging Face transformers library. We'll verify our understanding through code, examining how tokenizers handle special tokens internally and how to work with them in practice.

Examining BERT's Special Tokens

Let's start by inspecting BERT's special token configuration to confirm what we learned in the theory section:

As expected, BERT reserves the first vocabulary positions for special tokens. The [PAD] token at ID 0 follows a common convention: zero-padding is the default behavior in many frameworks, so placing [PAD] at index 0 aligns with standard tensor initialization.

Tokenizing with Special Tokens

Now let's observe special token addition in action. We'll encode text with and without special tokens to see exactly what the tokenizer adds:

The comparison reveals exactly what the tokenizer adds: [CLS] (ID 101) at the beginning and [SEP] (ID 102) at the end. The add_special_tokens=True flag (the default) triggers this wrapping automatically. Notice that the full encoding includes all three components we discussed: input IDs, attention mask (all ones for real tokens), and token type IDs (all zeros for a single segment).

Two-Segment Encoding

Let's now verify our understanding of segment handling by encoding a sentence pair:

The output confirms our worked example. Token type IDs switch from 0 to 1 exactly at the segment boundary, and both segments end with [SEP]. The model receives explicit information about which tokens belong to which segment, enabling it to learn appropriate cross-segment reasoning patterns.

Padding and Batching

Now let's examine the padding mechanism. We'll encode multiple sentences of different lengths to see how the tokenizer handles batching:

The output demonstrates the padding mechanism in action. Each sequence is padded to match the longest one (the medium sentence). The attention mask precisely tracks which positions are real (1) versus padding (0). Shorter sentences like "Tiny." have mostly zeros in their attention masks, ensuring the model ignores all those [PAD] tokens during attention computation.

The table below quantifies the computational cost of padding in our batch:

This table reveals a hidden cost of padding. While the attention mask prevents padding from corrupting representations, the model still processes every padding token through all its layers, consuming memory and computation for no benefit. Sentence 3, with only 5 real tokens padded to 13, wastes over 60% of its allocated computation. Techniques like dynamic batching (grouping similar-length sequences) and sequence packing (concatenating multiple sequences) can significantly reduce this overhead in production systems.

Comparing Tokenizers Across Models

We noted earlier that different architectures use different special token conventions. Let's verify this by comparing BERT, GPT-2, and T5:

The comparison reveals fundamental differences in architecture design. BERT uses [CLS] for sequence representation and [SEP] for boundaries, reflecting its bidirectional encoder nature. GPT-2 lacks a dedicated padding token, reflecting its original design for unpadded text generation. T5 uses </s> as both separator and end marker, consistent with its encoder-decoder design.

When fine-tuning GPT-2, you'll often need to set a padding token explicitly (commonly by reusing the EOS token, since GPT-2 wasn't designed for batched training).

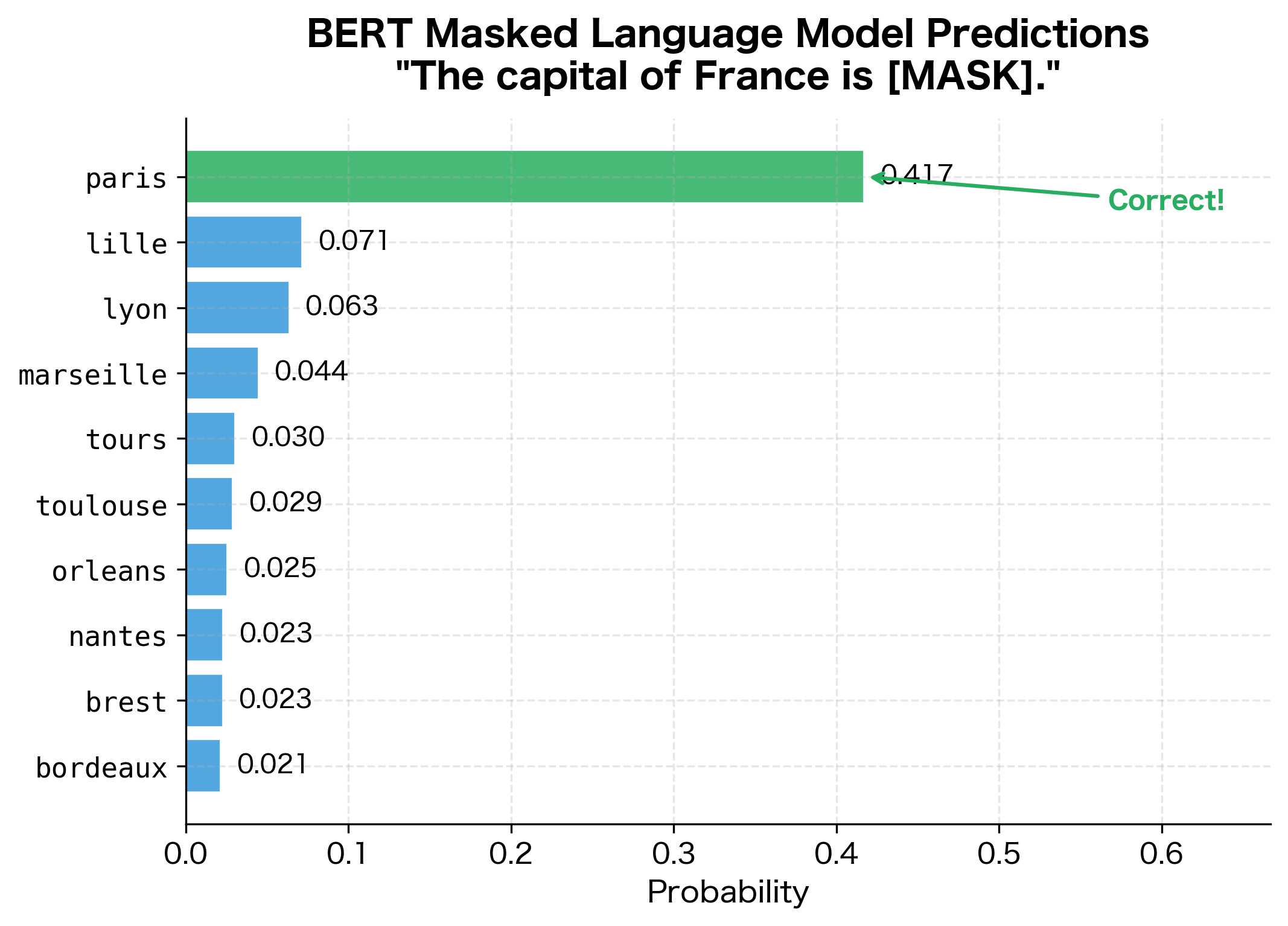

Masked Language Modeling

Having explored structural tokens, let's now see the [MASK] token in action. This token is central to BERT's pre-training. Let's verify that a trained model can actually predict masked words:

The model correctly predicts "paris" with high confidence. The probability distribution reveals how BERT has internalized factual knowledge through pre-training: it strongly favors the correct capital while assigning lower probabilities to plausible alternatives. This pattern of learning factual associations through self-supervised prediction is the foundation of how language models acquire world knowledge.

Adding Custom Special Tokens

Sometimes you need special tokens beyond the standard set. For example, a dialogue system might need speaker markers:

The custom tokens receive IDs at the end of the existing vocabulary (30522 onwards in BERT's case). Each custom token is treated atomically during tokenization. Notice how [SPEAKER1] remains intact rather than being split.

One critical detail: when using a model with custom tokens, you must resize its embedding layer to accommodate the new vocabulary size. Otherwise, token IDs beyond the original vocabulary size will cause index errors:

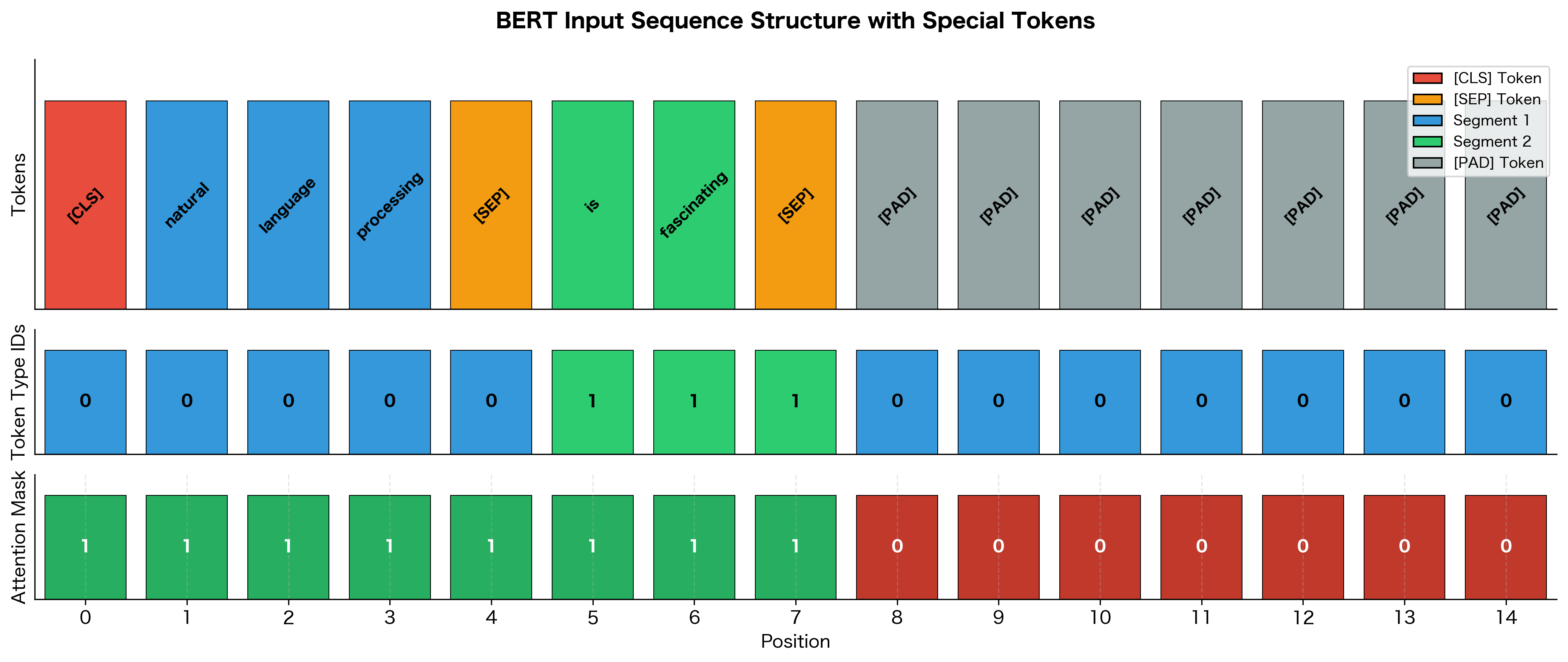

Visualizing Special Token Positions

To consolidate our understanding, let's create a comprehensive visualization showing how all the components (tokens, token type IDs, and attention masks) work together:

The visualization brings together everything we've learned. The top row shows the actual tokens with color-coding: red for [CLS], orange for [SEP], blue for segment 1, green for segment 2, and gray for padding. The middle row displays token type IDs. Notice how they switch from 0 to 1 at the segment boundary. The bottom row shows the attention mask with clear 1s for real tokens and 0s for padding.

This three-component structure (tokens, token types, and attention mask) is the complete input specification that transformers expect. Every input you send to BERT or similar models must include all three.

Special Tokens in Generation

We've focused on encoder models, but special tokens play equally important roles in generation. The EOS token, in particular, signals when the model should stop producing output:

Two decoding options are shown: with and without special tokens visible. For user-facing output, skip_special_tokens=True produces clean text. For debugging, seeing the special tokens helps verify that the model terminated properly (at <|endoftext|>) and didn't hit the maximum length cutoff.

The eos_token_id parameter defines the stopping condition for generation. Without it, the model would continue generating until hitting max_new_tokens, potentially producing incomplete or rambling output.

Limitations & Impact

While special tokens are essential for transformer architectures, they come with tradeoffs in terms of computational efficiency, model flexibility, and cross-architecture compatibility. Understanding these limitations helps practitioners make informed design decisions.

Limitations

Special tokens introduce subtle but important challenges. The [CLS] token, while convenient, forces sequence-level information into a single position. For long documents or complex reasoning tasks, this bottleneck can limit model performance. Some researchers have proposed using pooled representations from all tokens instead, or learning multiple aggregate representations.

The fixed vocabulary of special tokens can also be limiting. When adapting a pre-trained model to a new domain with new structural requirements (like code with specific delimiters, or legal documents with citation markers), you must add custom special tokens. This requires resizing the embedding layer and potentially fine-tuning to help the model learn useful representations for these new tokens. Models pre-trained without exposure to your custom tokens start with random embeddings, which can slow convergence.

Padding introduces computational inefficiency. Even with attention masks that prevent padding from influencing representations, the model still processes padding tokens through its layers, consuming memory and computation. Techniques like dynamic batching (grouping similar-length sequences) and sequence packing (concatenating multiple sequences with separators) help mitigate this, but add implementation complexity.

The reliance on specific special token formats creates compatibility challenges. A model trained with BERT-style tokens ([CLS], [SEP]) expects exactly that format during inference. Using the wrong special tokens, or forgetting them entirely, leads to degraded performance. This has led to the creation of standardized formats like the ChatML template for conversational models, but fragmentation persists across the ecosystem.

Impact

Despite these limitations, special tokens have become essential to modern NLP. The [CLS] token enabled BERT's approach to transfer learning, allowing a single pre-trained model to be fine-tuned for dozens of different tasks. The [MASK] token made self-supervised pre-training on unlabeled text possible at scale, eliminating the need for expensive labeled datasets.

The segment separation mechanism (using [SEP] and token type IDs) enabled models to jointly reason about multiple text pieces, unlocking tasks like question answering, natural language inference, and semantic similarity. Before this, models typically processed each input independently.

Custom special tokens have enabled specialized applications. Code models use tokens for different programming constructs. Dialogue systems use speaker tokens. Retrieval-augmented models use document boundary tokens. The flexibility to extend the special token vocabulary has made transformers adaptable to an enormous range of tasks beyond their original design.

Special tokens also established a convention for structuring model inputs that the entire field now follows. This standardization enabled the creation of shared benchmarks, reproducible research, and interoperable tools. When you use any modern NLP library, you're building on the foundation that special tokens provide.

Summary

Special tokens are the structural backbone of modern language models, providing essential signals that guide how transformers process text:

- [CLS] aggregates sequence-level information for classification tasks

- [SEP] marks boundaries between segments in multi-input tasks

- [PAD] enables batched processing by filling sequences to uniform length

- [MASK] enables self-supervised pre-training through masked language modeling

- [UNK] handles out-of-vocabulary items when subword tokenization isn't sufficient

Beyond these core tokens, models use:

- Token type IDs to distinguish segments within a sequence

- Attention masks to prevent padding from influencing real token representations

- Beginning/end tokens to mark sequence boundaries in generative models

- Custom special tokens for domain-specific structural needs

The design of special tokens reflects each model's training objectives and intended use cases. BERT's [CLS] and [SEP] support its bidirectional encoder architecture and sentence-pair tasks. GPT's simpler <|endoftext|> matches its autoregressive generation paradigm. T5's sentinel tokens enable its span corruption pre-training.

When working with special tokens, remember to add them during encoding (add_special_tokens=True), handle them appropriately during decoding (skip_special_tokens=True for clean output), and resize model embeddings when adding custom tokens. These small details often determine whether a model performs as expected or produces nonsensical results.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about special tokens in transformer models.

Comments