Learn how NER identifies and classifies entities in text using BIO tagging, evaluation metrics, and spaCy implementation.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Named Entity Recognition

Text is full of references to real-world entities: people, organizations, locations, dates, monetary amounts. Extracting these mentions automatically is one of the most practically useful NLP tasks. Named Entity Recognition (NER) identifies spans of text that refer to specific entities and classifies them into predefined categories.

Consider the sentence: "Apple announced that Tim Cook will visit Paris next Monday." A NER system should identify "Apple" as an organization, "Tim Cook" as a person, "Paris" as a location, and "next Monday" as a date. This extracted information powers applications from search engines to question answering systems to business intelligence tools.

NER sits at the intersection of sequence labeling and information extraction. Like POS tagging, it assigns labels to tokens. Unlike POS tagging, NER deals with multi-word spans and faces the challenge of detecting entity boundaries. This chapter covers entity types, the framing of NER as sequence labeling, boundary detection challenges, and evaluation methodologies.

Entity Types

NER systems categorize entities into a taxonomy of types. The specific categories depend on the application domain, but several core types appear across most NER systems.

A named entity is a real-world object that can be denoted with a proper name: a person, organization, location, or other specific entity. The term "named" distinguishes these from generic references: "the company" is not a named entity, but "Apple Inc." is.

Standard Entity Categories

The most common NER taxonomy includes three core categories that appear in virtually every system:

- PER (Person): Names of individuals, including fictional characters. Examples: "Albert Einstein", "Sherlock Holmes", "Dr. Smith"

- ORG (Organization): Companies, institutions, agencies, teams. Examples: "Google", "United Nations", "New York Yankees"

- LOC (Location): Geopolitical entities, physical locations, addresses. Examples: "France", "Mount Everest", "123 Main Street"

Extended taxonomies add additional categories for specific applications:

- DATE/TIME: Temporal expressions like "January 2024", "next Tuesday", "3:00 PM"

- MONEY: Monetary values like "$50 million", "€100", "fifty dollars"

- PERCENT: Percentage expressions like "25%", "a third"

- MISC (Miscellaneous): Entities that don't fit other categories, often events, products, or works of art

Let's explore entity types using spaCy's NER system:

The output shows spaCy correctly extracting diverse entity types from the text. Notice that "Apple Inc." is tagged as ORG (organization), while "Tim Cook" and "Emmanuel Macron" are PERSON entities. The model also recognizes "Paris" as a GPE (geo-political entity), extracts the date "January 15, 2024", identifies the monetary value "$2 billion" as MONEY, and captures "75%" as a PERCENT. The position columns show character offsets, which are useful for highlighting entities in the original text.

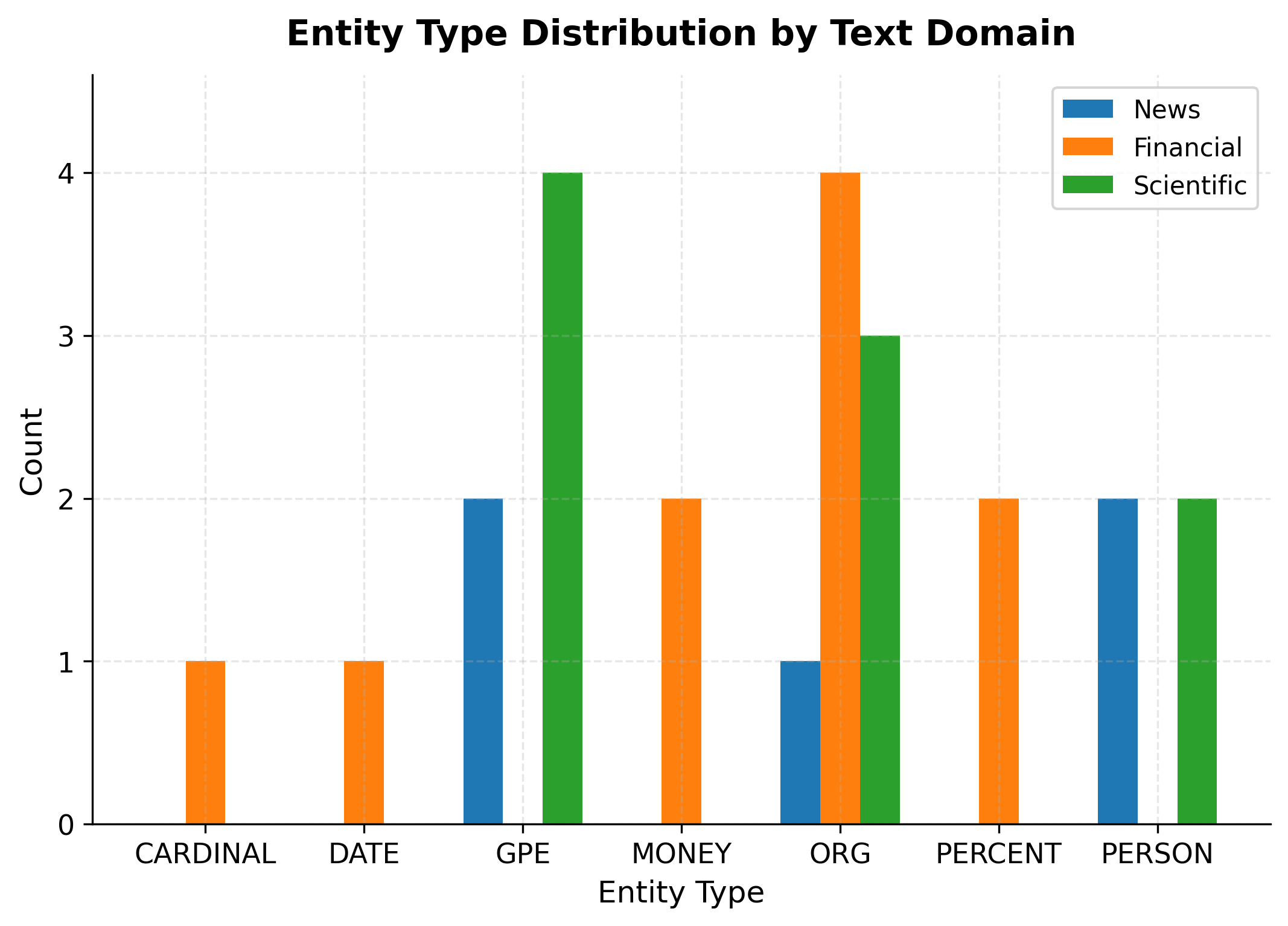

Entity Type Distributions

Different domains exhibit different entity distributions. News text contains many person and organization mentions. Scientific papers reference organizations and locations. Financial documents are dense with monetary values and percentages.

The distribution reveals clear domain patterns. Financial text is dense with MONEY and PERCENT entities, while news text contains more PERSON mentions (politicians) and ORG references. Scientific text shows a balance of ORG (institutions) and GPE (locations of research sites). These patterns matter for NER system design. Training data should reflect the target domain's entity mix, and evaluation should weight entity types according to their importance in the application.

NER as Sequence Labeling

NER is fundamentally a sequence labeling problem: given a sequence of tokens, assign a label to each token indicating whether it's part of an entity and, if so, which type. This framing connects NER to other sequence labeling tasks like POS tagging, allowing us to apply similar models and techniques.

The key difference from POS tagging is that entities span multiple tokens. "Tim Cook" is a single PERSON entity spanning two tokens. "United States of America" spans four tokens. The sequence labeling formulation must handle these multi-token spans.

Token-Level Labels

The simplest approach assigns each token one of three labels:

- B-TYPE: Beginning of an entity of TYPE

- I-TYPE: Inside (continuation of) an entity of TYPE

- O: Outside any entity

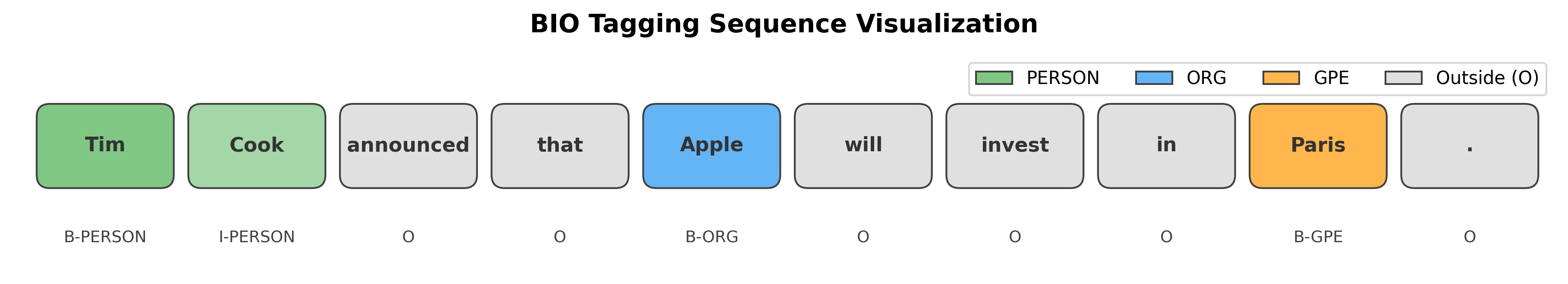

This is the BIO tagging scheme, which we'll explore in depth in the next chapter. For now, let's see how it works:

Notice how "Tim" receives the B-PERSON tag (beginning of a person entity) while "Cook" gets I-PERSON (inside/continuation). This two-token sequence forms a single PERSON entity. Similarly, "Apple" and "Paris" each receive B-ORG and B-GPE tags as single-token entities. All other tokens are tagged O (outside), indicating they're not part of any entity.

The B (beginning) tag marks the first token of an entity, while I (inside) tags mark continuation tokens. The O (outside) tag marks tokens that aren't part of any entity. This scheme handles adjacent entities of the same type by using B tags to signal new entity boundaries.

From Classification to Structured Prediction

Token-level classification treats each token independently, but entity spans have structure. Consider a sequence of tokens with corresponding labels . If token receives label , then the preceding label must be either B-PER or I-PER. A sequence starting with I-PER violates the tagging constraints.

This structural dependency makes NER a structured prediction problem. Models must consider not just individual token features but also the consistency of the entire label sequence. Approaches like Conditional Random Fields (CRFs) explicitly model these dependencies, which we'll cover in later chapters.

The valid sequences demonstrate proper BIO structure: entities start with B and continue with I of the same type. The invalid sequences show common violations. Starting with I-PER is invalid because there's no preceding B-PER to begin the entity. A B-PER followed by I-ORG is invalid because the entity type must be consistent throughout the span. An orphan I-LOC without a preceding B-LOC is likewise invalid.

Understanding these constraints is crucial for both training NER models and decoding their predictions. Many NER systems add a constraint layer that ensures outputs always form valid BIO sequences.

Nested Entity Challenges

Real text often contains nested entities, where one entity is contained within another. Consider "Bank of America headquarters in Charlotte." The full location "Bank of America headquarters in Charlotte" contains the organization "Bank of America" and the location "Charlotte."

Nested entities occur when one named entity mention is contained within another. Standard sequence labeling with BIO tags cannot represent nested structures since each token receives exactly one label.

Standard BIO tagging forces a choice: you can only assign one label per token. Different strategies handle this limitation.

Flat Annotation

Most NER datasets and systems use flat annotation, where nested entities are resolved by choosing one level. Common strategies include:

- Outermost entity: Label the largest span

- Innermost entities: Label only the most specific mentions

- Head-based: Label based on the syntactic head

spaCy and most production NER systems use flat annotation. This works well for many applications, but loses information when nesting matters.

Nested NER Approaches

When nested entities are important, specialized approaches can capture them:

- Multi-layer tagging: Run multiple passes, each extracting one nesting level

- Span-based models: Score all possible spans rather than labeling tokens

- Constituency parsing-based: Use tree structures to represent nesting

For just four tokens, we generate 10 candidate spans. Notice this includes both "New York" (a potential location) and "New York Times" (a potential organization), allowing a nested NER system to recognize both. A span-based model would score each of these spans for each entity type, keeping only those with high confidence scores.

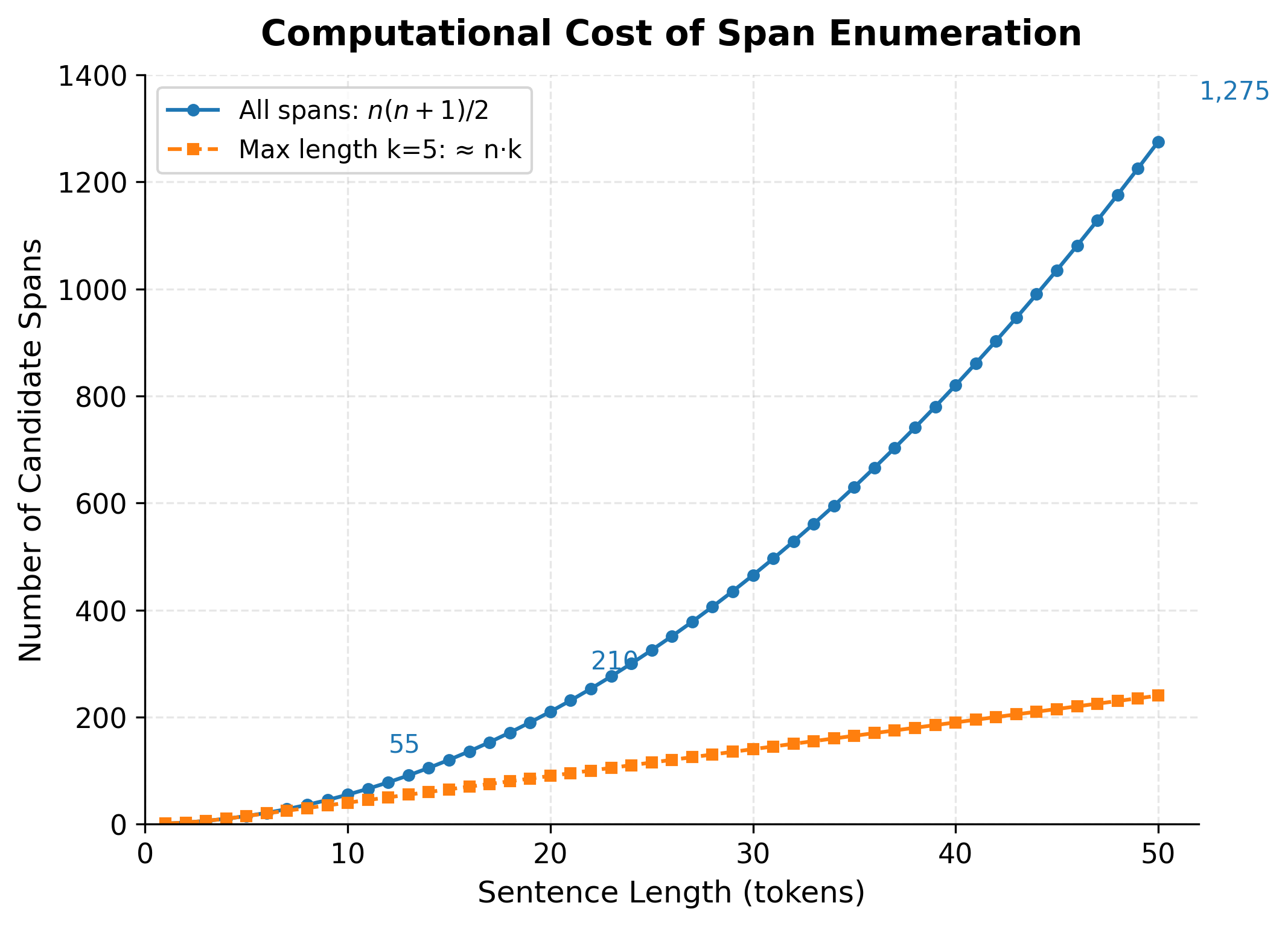

The Computational Cost of Span Enumeration

Span-based approaches are elegant conceptually: enumerate all possible spans and classify each one. This naturally handles nesting since overlapping spans can receive different labels. But this flexibility comes with a computational cost that grows rapidly with sentence length.

To understand the cost, let's count how many spans exist in a sentence of tokens. A span is defined by its starting position (any token from 1 to ) and its ending position (any token from the start to ). For each starting position , we can form spans ending at positions , , , ..., up to . This gives us:

- Starting at position 1: possible spans

- Starting at position 2: possible spans

- Starting at position 3: possible spans

- ...

- Starting at position : 1 possible span

The total is , which is the sum of the first integers:

This quadratic growth means span enumeration becomes expensive for long sentences. A 10-token sentence has 55 spans. A 20-token sentence has 210 spans. A 50-token sentence has 1,275 spans to classify. For each span, the model must compute features and score it against each entity type, multiplying the computational burden.

In practice, span-based NER models mitigate this cost by limiting the maximum span length. Most named entities are short (1-5 tokens), so ignoring spans longer than some threshold loses little recall while dramatically reducing computation. With a maximum span length of , the number of spans becomes approximately rather than , making the approach tractable for longer documents.

Entity Boundary Detection

Detecting where entities start and end is often harder than classifying entity types. The word "New" in "New York" is clearly part of a location, but in "New policy announced" it's not part of any entity.

Boundary Ambiguity

Entity boundaries are ambiguous for several reasons. First, modifiers may or may not be included: is it "President Biden" or just "Biden"? Second, compound entities are tricky: does "Apple iPhone 15" contain one entity or two? Third, coordination creates challenges: in "Microsoft and Google", are there two separate ORG entities or one?

The results reveal interesting boundary decisions. "Joe Biden" is recognized without "President", but "United States Department of Defense" is captured as a complete span. For the Apple example, the model may or may not include "iPhone 15 Pro Max" as part of the entity. The coordination case shows how "Microsoft", "Google", and "Meta" are correctly identified as three separate ORG entities rather than one.

Annotation guidelines must make consistent decisions about these edge cases. Different datasets make different choices, which means NER systems trained on one dataset may produce different boundaries than systems trained on another.

Titles and Honorifics

A common boundary question is whether titles should be included in person names. "Dr. Smith" could be annotated as a single PERSON entity or as a title plus a PERSON.

The spaCy model typically excludes titles from person names, treating "Dr." as a separate token. This is a design choice that affects downstream applications. If your use case requires titles, you may need to extend entity spans post-hoc.

NER Evaluation

How do we know if a NER system is any good? This question is more subtle than it first appears. Unlike classification tasks where each input has exactly one label, NER involves identifying spans of varying length and assigning types to them. A prediction might get the entity type right but the boundaries wrong, or it might find some entities but miss others entirely. We need evaluation metrics that capture these nuances.

The Challenge of Measuring NER Performance

Consider a sentence where the gold standard annotation marks "New York Times" as an ORG entity. Suppose our NER system predicts "New York" as a LOC entity instead. How should we score this?

- The system found something at roughly the right location

- But the span is too short (missing "Times")

- And the type is wrong (LOC instead of ORG)

Should this receive partial credit? Zero credit? The answer depends on your evaluation paradigm, and understanding these choices is crucial for interpreting NER benchmarks.

Exact Match Evaluation

The standard approach in NER evaluation is exact match: a prediction counts as correct only if it matches a gold entity exactly in both span boundaries and entity type. This binary decision creates a clean framework built on three fundamental counts.

When comparing predicted entities against gold standard annotations, every entity falls into exactly one of three categories:

-

True Positives (): Predictions that exactly match gold entities. The span boundaries must be identical (same start and end positions), and the entity type must match.

-

False Positives (): Predictions that don't match any gold entity. This includes entities with wrong boundaries (even by one token), wrong types, or completely spurious predictions.

-

False Negatives (): Gold entities that the system failed to predict. These represent missed entities that should have been found.

From these three counts, we derive the standard evaluation metrics. Precision answers the question: "Of all the entities we predicted, how many were correct?"

A system with high precision makes few mistakes when it does predict an entity, but it might be overly cautious and miss many entities. Think of a conservative NER system that only predicts entities when it's highly confident.

Recall answers the complementary question: "Of all the entities that exist, how many did we find?"

A system with high recall finds most entities but might also predict many false positives. Think of an aggressive NER system that marks anything that could possibly be an entity.

Neither metric alone tells the full story. A system that predicts nothing has perfect precision (no false positives) but zero recall. A system that marks every token as an entity has perfect recall but terrible precision. We need a metric that balances both concerns.

The F1 score provides this balance as the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

The harmonic mean, rather than the arithmetic mean, ensures that F1 is low when either precision or recall is low. You cannot achieve a high F1 by excelling at one metric while failing at the other. This property makes F1 the standard single-number summary for NER performance.

Implementing Exact Match Evaluation

Let's implement these metrics and see how they work on a concrete example. We'll compare a set of predicted entities against gold standard annotations.

Now let's create a realistic example. Consider a sentence with three gold entities, and a NER system that makes some correct predictions but also some errors:

Let's trace through the evaluation logic step by step. Of our 4 predictions, only 2 exactly match gold entities ("Tim Cook" and "Apple"). The prediction for "Paris" fails because the boundary is wrong (tokens 8-10 instead of 8-9), even though we correctly identified the location. The DATE prediction at tokens 12-13 is completely spurious. This gives us:

- (the two exact matches)

- (boundary error + spurious prediction)

- (the missed "Paris" entity)

Plugging into our formulas:

- Precision (half our predictions were correct)

- Recall (we found two of three entities)

- F1

The 57% F1 score reflects that our system is mediocre: it makes too many errors and misses too many entities. Notice how the boundary error for "Paris" counts as both a false positive (wrong prediction) and contributes to a false negative (missed entity). Exact match evaluation is strict, which encourages models to learn precise boundaries.

Partial Match: An Alternative Paradigm

Exact match can feel harsh. The prediction "New York" for a gold entity "New York Times" receives zero credit, even though two of three tokens overlap. Partial match evaluation schemes give credit for overlapping predictions, typically proportional to the token overlap.

If the system predicts "New York" for a gold entity "New York Times", partial match might give 2/3 credit for the two overlapping tokens. This is more forgiving but complicates interpretation: a system with 80% partial match F1 might still make frequent boundary errors.

Most NER benchmarks use exact match because it provides a clear, unambiguous standard. However, for applications where approximate entity identification is acceptable, partial match metrics can provide additional insight into system behavior.

Per-Type Evaluation

Overall metrics can hide disparities across entity types. A system might excel at detecting person names but struggle with organizations. Per-type breakdown reveals these patterns:

The per-type breakdown reveals distinct performance patterns across entity categories:

| Entity Type | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOC | 100% | 50% | 67% | 4 |

| ORG | 67% | 100% | 80% | 2 |

| PERSON | 100% | 67% | 80% | 3 |

The system achieves perfect precision on PERSON and LOC entities, meaning every prediction for these types was correct. However, recall gaps tell a different story: the system missed one of three PERSON entities (67% recall) and two of four LOC entities (50% recall). For ORG, the pattern reverses: the system found all gold ORG entities (100% recall) but made one spurious prediction, dropping precision to 67%. This per-type analysis reveals that different entity types may require different improvement strategies.

Standard Benchmarks

NER systems are typically evaluated on standard benchmark datasets:

- CoNLL-2003: News articles with PER, LOC, ORG, MISC tags. The most widely used benchmark for English NER.

- OntoNotes 5.0: Diverse genres with 18 entity types including dates, times, quantities.

- ACE 2005: Focuses on person, organization, location, facility, geo-political entity, vehicle, weapon.

- WNUT: Social media text, particularly challenging due to informal language.

The benchmark statistics reveal a striking performance gap. CoNLL-2003 and OntoNotes achieve state-of-the-art F1 scores above 92%, reflecting the relative consistency of formal news and web text. The WNUT benchmark on social media text shows only 56.5% F1, demonstrating how informal language, novel entities, and creative spelling challenge NER systems trained on formal text. The WNUT benchmark remains challenging because social media text contains novel entities, creative spelling, and informal grammar that confound models trained on formal text.

Implementing NER with spaCy

Let's build a complete NER pipeline using spaCy, demonstrating entity extraction, visualization, and practical post-processing.

The context reveals how surrounding words help identify and classify entities. "Elon Musk's Tesla" shows a possessive construction linking a person to an organization. The phrase "rival Ford Motor Company" provides a semantic cue that this is a competitor company. Context is particularly valuable for ambiguous mentions where the same text could refer to different entity types.

Adding context around entities helps with interpretation and debugging. You can see how surrounding words provide disambiguation cues.

Entity Linking and Normalization

Raw entity mentions often need normalization. "Tesla", "Tesla Inc.", and "Tesla Motors" all refer to the same company. Entity linking connects mentions to canonical identifiers in a knowledge base.

Production NER systems often include a normalization step that maps mentions to unique identifiers. This enables aggregation across documents and linking to knowledge bases like Wikidata or corporate databases.

Aggregating Entity Mentions

When processing multiple documents, you often want to count entity occurrences and track co-occurrence patterns:

Entity aggregation is essential for applications like entity-based document clustering, co-reference resolution across documents, and building knowledge graphs from text.

Key Parameters

When working with spaCy for NER, several parameters and configuration options affect performance:

-

Model size (

en_core_web_sm,en_core_web_md,en_core_web_lg,en_core_web_trf): Larger models generally achieve better accuracy. The transformer-basedtrfmodel provides the best performance but requires more memory and computation. -

Entity labels: spaCy's models recognize a fixed set of entity types (PERSON, ORG, GPE, DATE, MONEY, etc.). Custom entity types require fine-tuning with annotated training data.

-

Context window: Entity recognition depends on surrounding context. Short snippets may lack sufficient context for disambiguation, while very long documents may exceed memory limits.

-

Batch processing: For large document collections, process documents in batches using

nlp.pipe()with then_processparameter for parallel processing. -

Entity ruler: For domain-specific entities with known patterns, combine statistical NER with rule-based matching using spaCy's

EntityRulercomponent.

Limitations and Challenges

NER has achieved impressive accuracy on benchmark datasets, but significant challenges remain in real-world applications.

The most pervasive issue is domain shift. NER systems trained on news text struggle with biomedical literature, legal documents, social media, and other specialized domains. Domain-specific entities may not exist in training data, and domain-specific patterns may confuse general-purpose models. A model that excels at detecting political figures and companies may fail entirely when confronted with drug names, gene symbols, or legal citations. The practical impact is substantial: deploying a pre-trained NER system on a new domain typically requires at least some domain-specific fine-tuning to achieve acceptable performance.

Rare and emerging entities pose another fundamental challenge. Language evolves continuously, with new people, organizations, products, and concepts entering the discourse. NER systems can only recognize what they've seen patterns for. A model trained before 2023 wouldn't recognize "ChatGPT" as a product or "Anthropic" as an organization. This temporal gap means production NER systems require regular retraining or sophisticated mechanisms for detecting novel entities.

Ambiguous entity types also cause persistent errors. Is "Washington" a person, a location, or an organization? All three are possible depending on context: George Washington (person), Washington D.C. (location), Washington Nationals (organization). Even with context, some cases remain genuinely ambiguous. The same proper noun can refer to different entity types in different sentences, and NER systems must learn subtle contextual cues to disambiguate.

Summary

Named Entity Recognition extracts references to real-world entities from text, classifying them into categories like person, organization, and location. The key concepts covered in this chapter include:

Entity types define the taxonomy of entities a system can recognize. Standard categories include PER, ORG, LOC, and extensions like DATE, MONEY, and PERCENT. Domain-specific applications may require custom entity types.

NER as sequence labeling assigns labels to each token indicating entity membership. The BIO scheme marks entity boundaries with B (beginning), I (inside), and O (outside) tags, enabling multi-token entity spans.

Nested entities occur when entities contain other entities. Standard sequence labeling cannot represent nesting, requiring either flat annotation choices or specialized span-based approaches.

Entity boundaries are often ambiguous, particularly with modifiers, titles, and compound entities. Annotation guidelines must make consistent decisions that models learn to replicate.

Evaluation uses exact match metrics (precision, recall, F1) where predictions must match gold entities exactly in both span and type. Per-type breakdown reveals performance disparities across entity categories.

The next chapter explores BIO tagging in depth, covering scheme variants, conversion algorithms, and implementation details that underpin practical NER systems.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about Named Entity Recognition.

Comments