Learn how ELECTRA achieves BERT-level performance with 1/4 the compute by detecting replaced tokens instead of predicting masked ones.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

ELECTRA

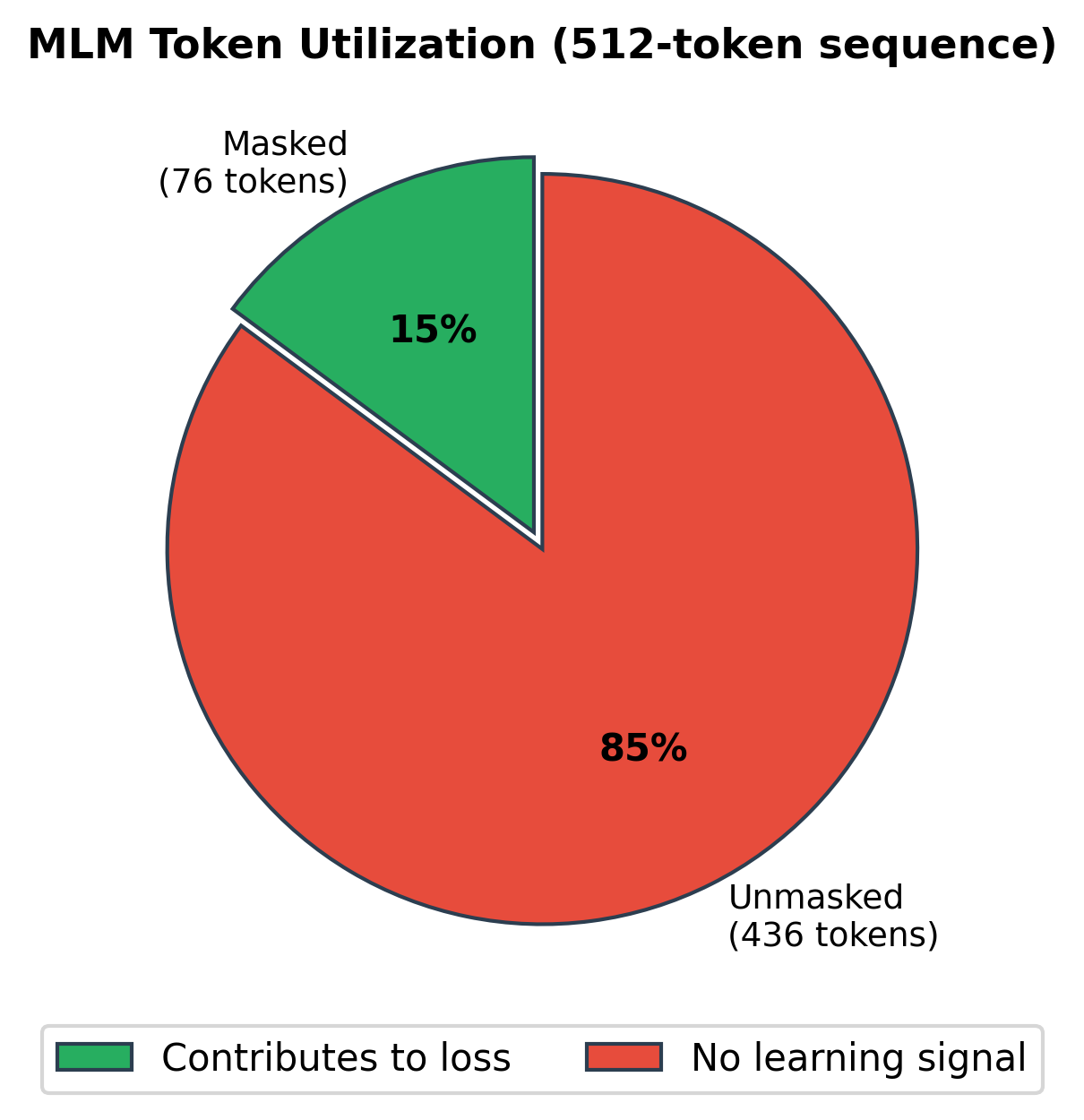

BERT learns language by predicting masked tokens. But there's a fundamental inefficiency in this approach: the model only learns from the 15% of tokens that are masked. The remaining 85% flow through the network, consuming compute, but contribute nothing to the loss. What if we could learn from every token instead?

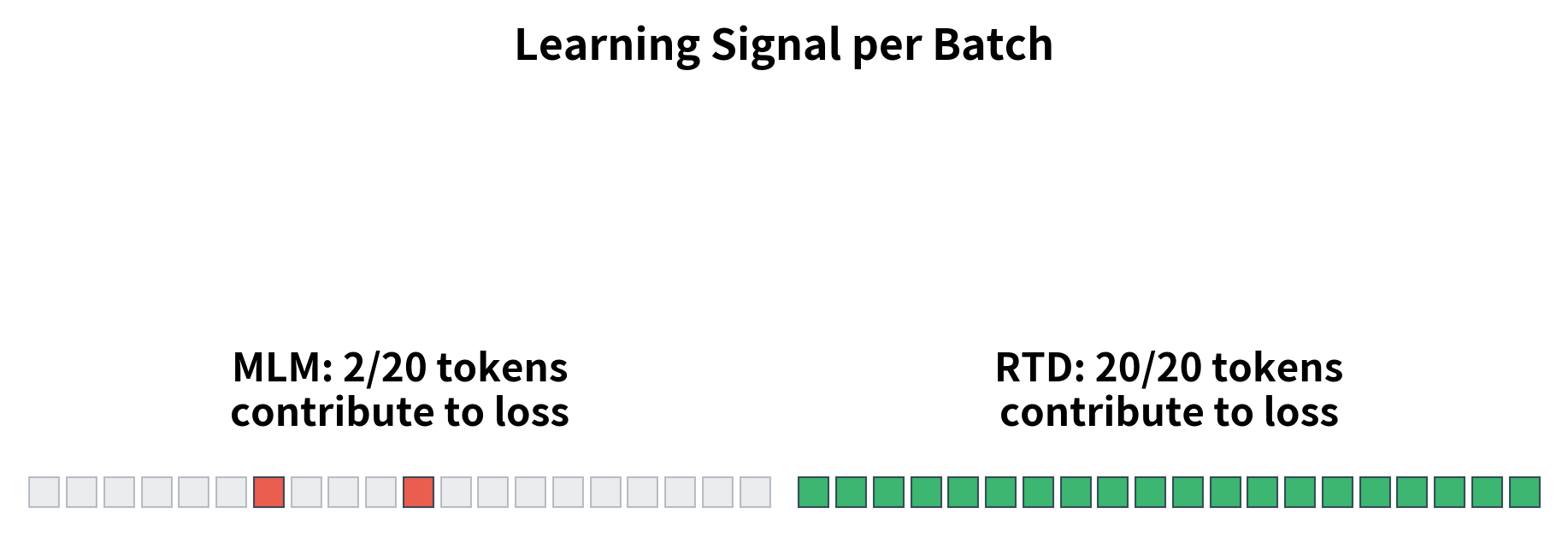

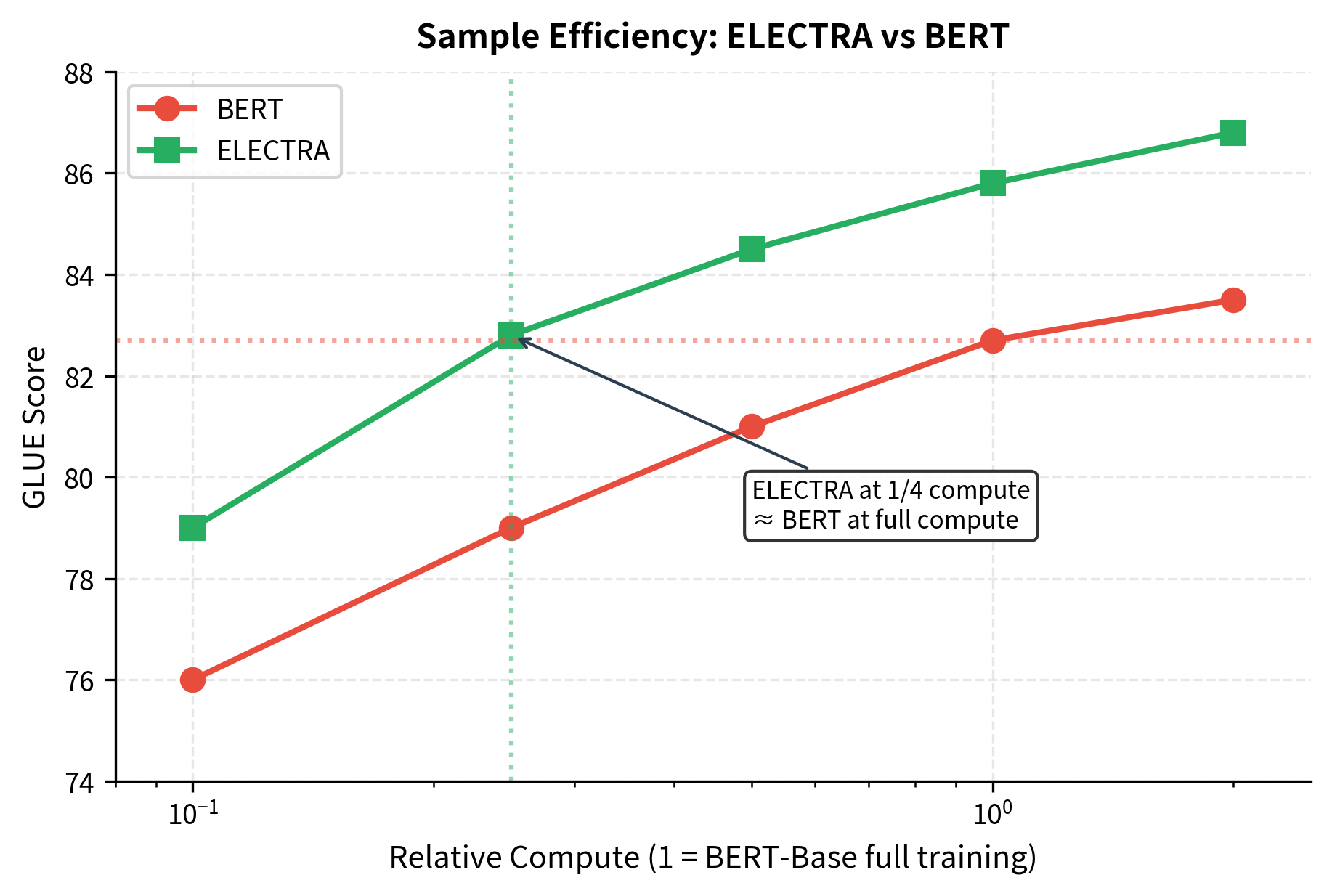

ELECTRA (Efficiently Learning an Encoder that Classifies Token Replacements Accurately) answers this question with a clever training paradigm. Instead of masking tokens and predicting them, ELECTRA replaces tokens with plausible alternatives and trains a model to detect which tokens were swapped. Every position now provides a learning signal, not just the masked ones. This seemingly simple change dramatically improves sample efficiency: ELECTRA matches BERT's performance with just 1/4 of the compute and exceeds it when given equal resources.

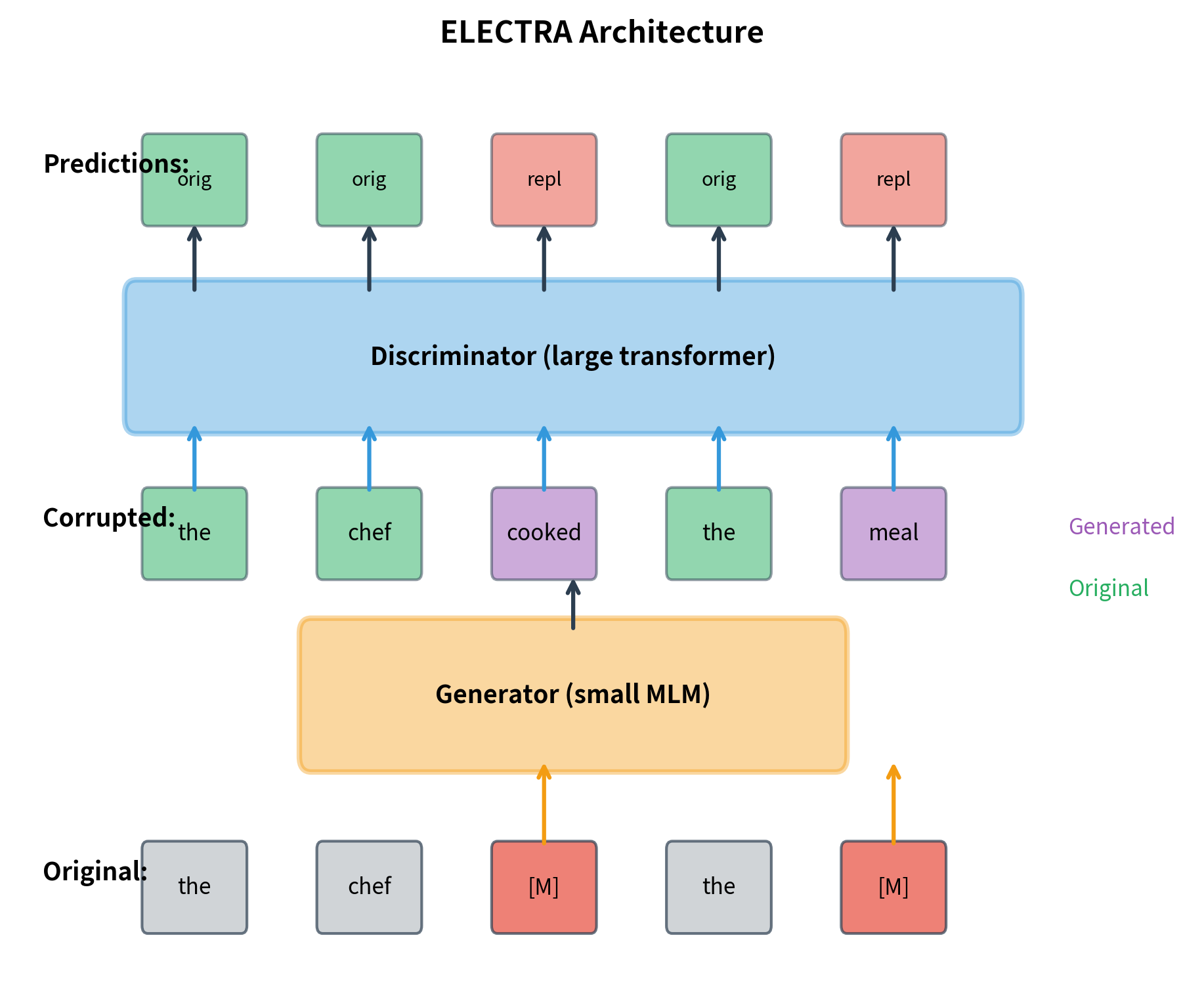

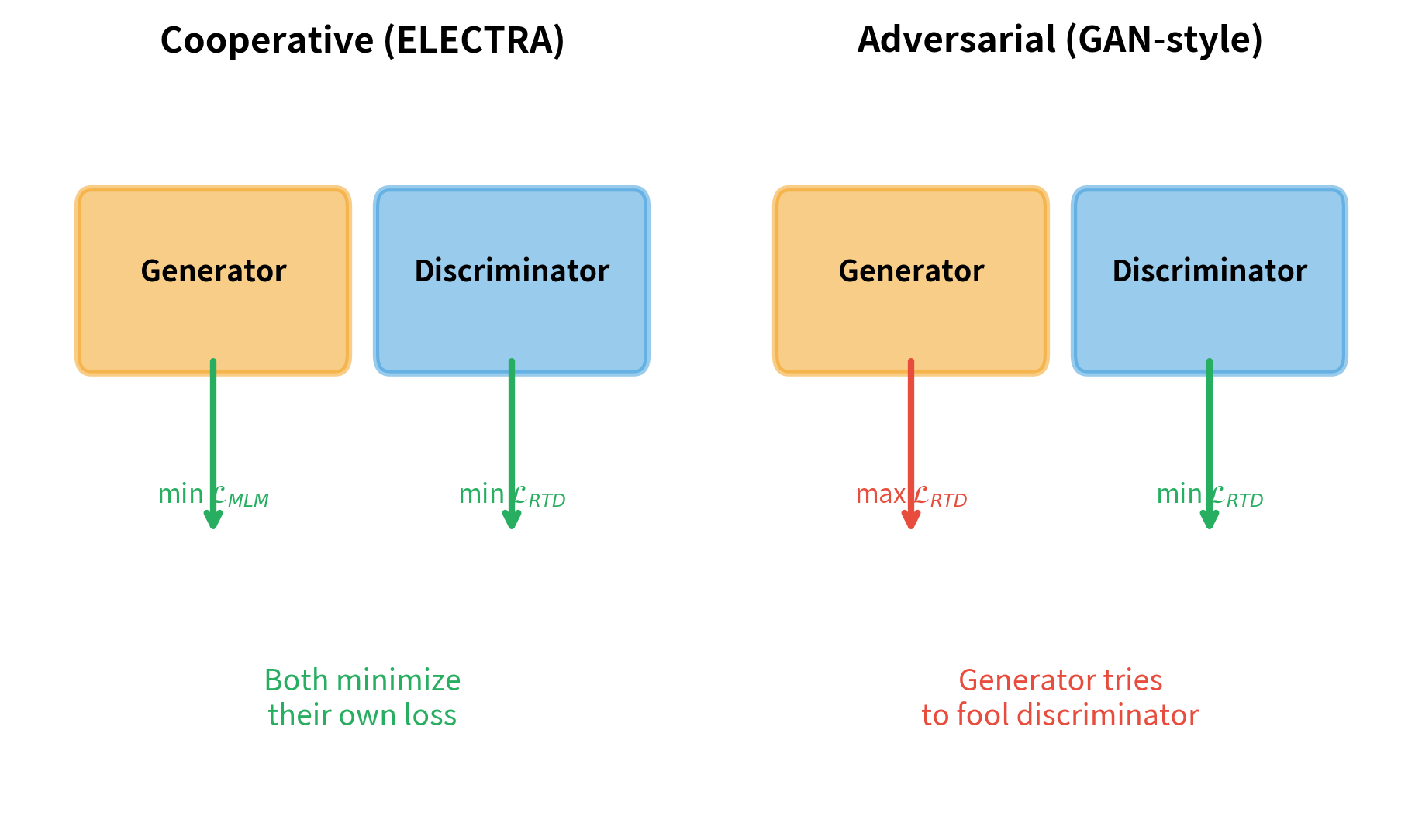

The approach borrows ideas from generative adversarial networks. A small generator network produces realistic token replacements. A larger discriminator network learns to distinguish original tokens from generated ones. But unlike GANs, the two networks cooperate through shared training rather than competing in a minimax game. This chapter explores how ELECTRA's replaced token detection objective works, why it's so efficient, and how to implement it from scratch.

The Inefficiency of Masked Language Modeling

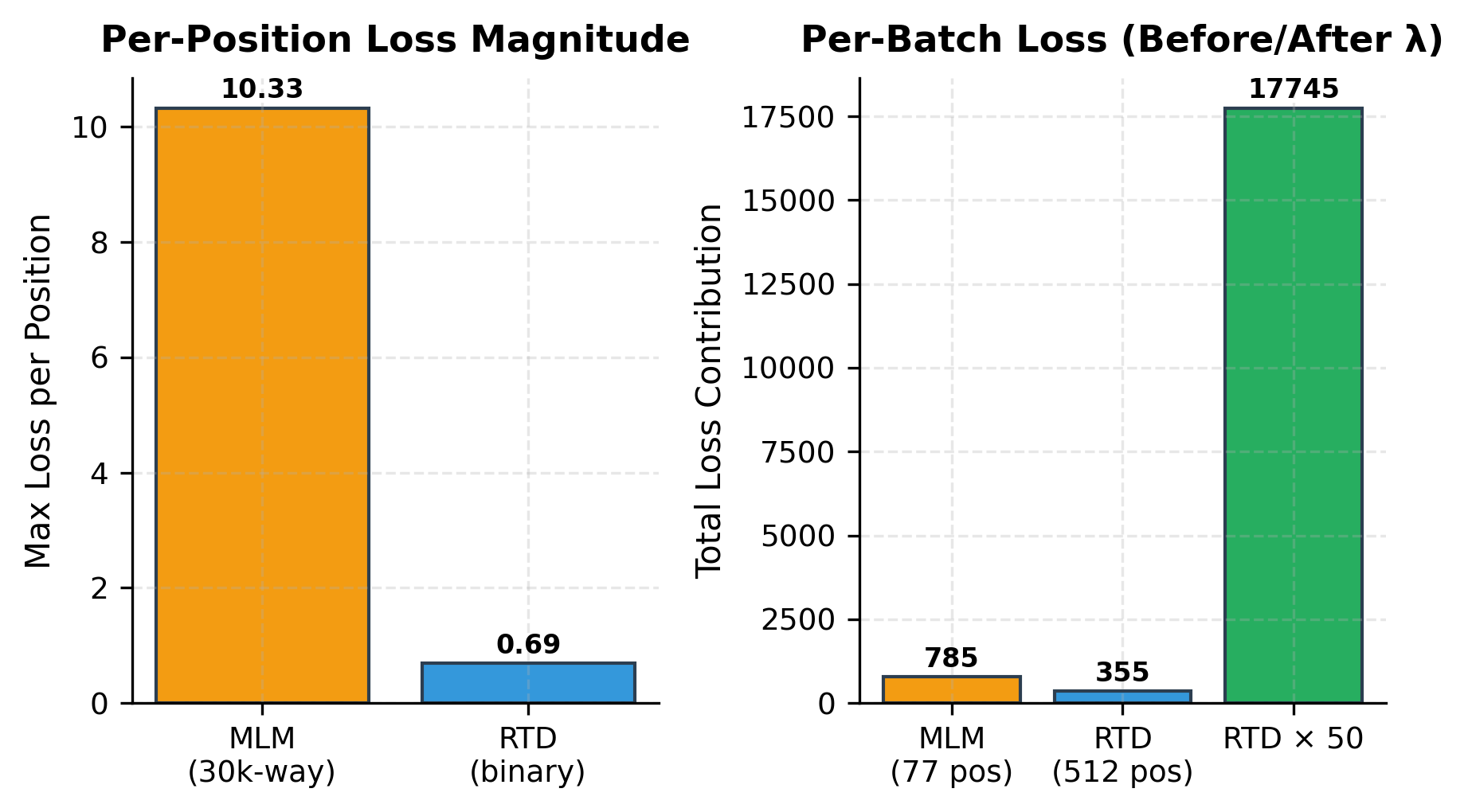

Let's quantify what BERT wastes. For a 512-token sequence with 15% masking, only 77 tokens contribute to the MLM loss. The other 435 tokens pass through 12 transformer layers, consuming attention computations and memory, but generate no gradient signal. They're essentially free riders.

Only 15% of tokens contribute to learning. This is inherent to the MLM objective: predicting from a large vocabulary is hard, so we can only mask a small fraction without destroying context. Mask too many tokens and the task becomes impossible.

ELECTRA sidesteps this limitation by changing the task entirely. Instead of predicting masked tokens (a 30,000-way classification problem), the model classifies each token as original or replaced (a binary classification problem). Binary classification per token means every position can contribute to the loss without overwhelming the model.

A pre-training objective where the model predicts, for each token in a sequence, whether it is the original token or a replacement generated by a separate model. Unlike MLM's vocabulary-sized softmax, RTD uses a simple sigmoid classifier, enabling learning from every token position.

The Generator-Discriminator Architecture

ELECTRA uses two transformer networks: a generator and a discriminator. The generator is a small masked language model that proposes plausible replacements for masked tokens. The discriminator is a larger network that learns to detect which tokens were replaced. Despite the naming, this is not adversarial training in the GAN sense. Both networks are trained jointly to minimize their respective losses.

The key insight is that the generator doesn't need to be good, just good enough to fool a naive discriminator occasionally. A small generator (1/4 to 1/3 the discriminator's size) works well because it produces plausible but imperfect replacements. If the generator were perfect, every replacement would match the original, and the discriminator would learn nothing. If the generator were random, the replacements would be obviously wrong, making discrimination trivial. The sweet spot is a generator that produces contextually appropriate tokens that are sometimes, but not always, correct.

Generator Training

The generator is a small masked language model. It receives the original sequence with some positions masked and predicts tokens for those positions. Training follows the standard MLM objective: minimize cross-entropy between predicted and original tokens.

The generator samples from its predicted distribution rather than taking the argmax. Sampling introduces diversity: the same masked position might get different replacements across training steps. This prevents the discriminator from memorizing specific generator mistakes and forces it to learn genuine linguistic features.

The generator is compact at roughly 10M parameters, much smaller than the discriminator. With a 15% masking rate, we masked 10 positions out of 64 tokens (batch of 2 × 32).

The generator is deliberately small. In the original ELECTRA paper, the generator has 1/4 to 1/3 the parameters of the discriminator. A larger generator would produce better replacements, but paradoxically, this hurts training. The discriminator needs somewhat detectable replacements to learn from. Perfect replacements (indistinguishable from originals) provide no signal.

Discriminator Training

The discriminator is the main model. It receives the corrupted sequence (where masked positions have been filled by the generator) and predicts for each token whether it's original or replaced. Unlike the generator's vocabulary-sized output, the discriminator outputs a single logit per position.

The discriminator loss is binary cross-entropy computed over all tokens, not just the ones that were candidates for replacement. This is the key to ELECTRA's efficiency: the loss involves every position.

Let's trace through a complete forward pass to see how the pieces connect:

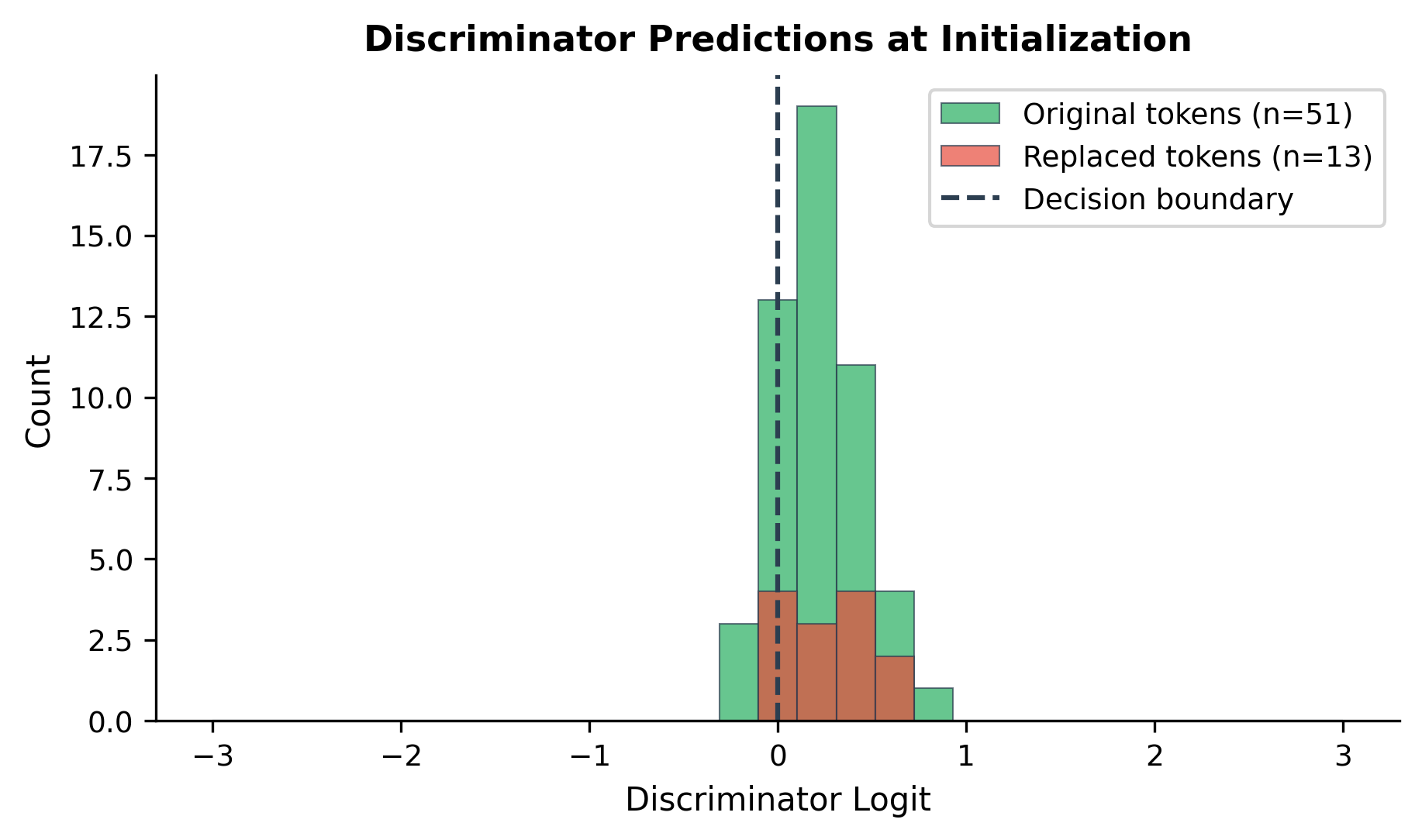

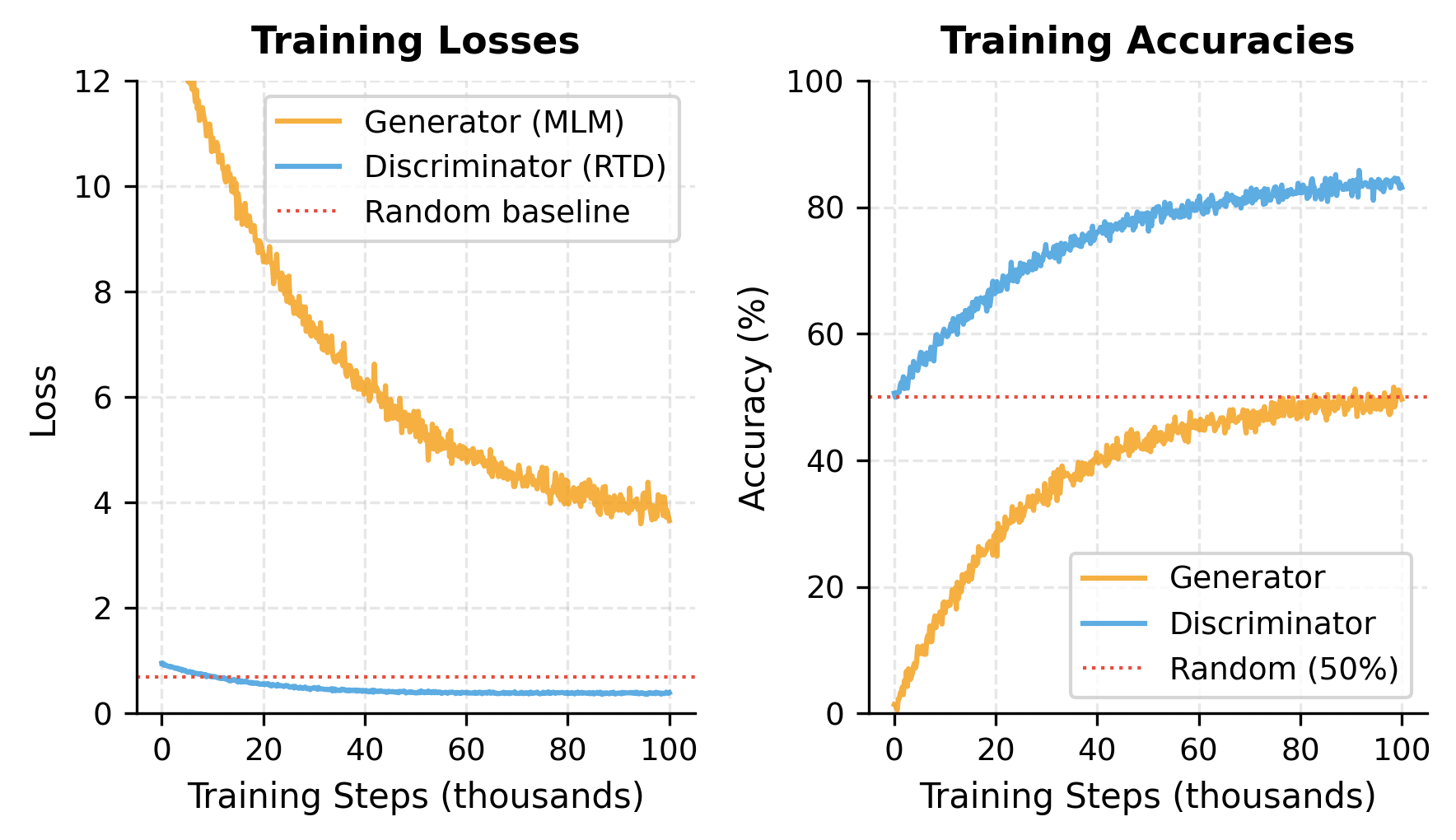

The discriminator has roughly 85M parameters, significantly larger than the generator. The replacement rate is lower than the 15% masking rate because the generator sometimes predicts the correct original token. The discriminator loss starts near the random baseline (0.69, which is for binary classification), indicating the untrained model has no ability to distinguish original from replaced tokens.

Notice that the generator can produce the same token as the original. When it does, that position is not "replaced" even though it went through the generator. This means the actual replacement rate is typically lower than the masking rate. The discriminator learns to identify both truly replaced tokens and those where the generator happened to guess correctly.

The Replaced Token Detection Objective

The RTD objective trains the discriminator to predict is_replaced for every token. Let's formalize the setup before presenting the loss function.

Problem setup:

- We start with an original sequence containing tokens

- A random subset of positions is selected for masking (typically 15% of positions)

- The generator receives the sequence with

[MASK]tokens at positions in and produces replacement tokens for each - The corrupted sequence combines original and generated tokens: for positions not in , and equals the generator's sampled token for positions in

Note that even at masked positions, the generator might sample the same token as the original. These positions are technically "original" for the discriminator's task, since no replacement occurred.

The discriminator outputs logits for each position. The RTD loss is the standard binary cross-entropy, summed across all positions in the sequence:

where:

- : the total number of tokens in the sequence (e.g., 512)

- : the discriminator's raw logit output at position , representing how confident the model is that the token was replaced

- : the sigmoid function, which converts the logit to a probability between 0 and 1

- : the ground truth label, equal to 1 if the token at position was replaced by the generator, and 0 if it's the original token

The loss decomposes into two cases: when (token was replaced), the loss is , encouraging the model to output a high logit. When (token is original), the loss is , encouraging a low logit. The sum runs over all positions, not just the masked ones. This is the crucial difference from MLM: every token contributes to learning.

Joint Training

ELECTRA trains the generator and discriminator simultaneously. The total loss combines both objectives into a single scalar that drives gradient updates:

where:

- : the masked language modeling loss for the generator

- : the replaced token detection loss for the discriminator

- : a weighting factor (typically 50) that balances the two losses

The high weight on RTD ensures the discriminator is the primary focus of training. Without this upweighting, the generator's gradients would dominate because MLM involves a 30,000-way classification (much harder per token than binary classification).

The generator's MLM loss is computed only at masked positions:

where:

- : the set of masked positions (typically 15% of sequence length)

- : the original token at position (the target we want the generator to predict)

- : the input sequence with

[MASK]tokens at positions in - : the probability the generator assigns to the correct token given the masked input

This is standard cross-entropy loss: the generator is rewarded for assigning high probability to the original tokens at masked positions.

At initialization, both networks perform near chance level: the generator accuracy is close to random guessing among 30,000 vocabulary tokens, and the discriminator accuracy hovers around 50% for binary classification. The generator loss is high (around 10, reflecting the log of vocab size), while the discriminator loss is near 0.69 (the random baseline for binary cross-entropy). During training, both losses decrease as the generator learns to predict masked tokens and the discriminator learns to detect replacements.

The weight is important and deserves explanation. The generator loss is computed over approximately 15% of tokens with a 30,000-way classification at each position, while the discriminator loss is computed over 100% of tokens but with only binary classification at each position.

The cross-entropy loss magnitude scales with the log of the number of classes: for MLM, this is approximately per position, while for RTD it's per position. Even though RTD has more positions, the per-position loss magnitude is much smaller. Without upweighting RTD, the MLM gradients would dominate the shared embeddings. The factor ensures both networks receive comparable gradient magnitudes, allowing the discriminator to learn effectively.

Why No Adversarial Training?

You might wonder why ELECTRA doesn't use adversarial training like a GAN. The generator could try to fool the discriminator, making training competitive rather than cooperative. The ELECTRA authors experimented with this and found it hurt performance.

The problem is the discreteness of text. GANs work well for continuous outputs (images, audio) where small gradient-based adjustments smoothly improve quality. Text is discrete: you either sample token 7842 or you don't. There's no gradient to flow back from the discriminator's judgment of that specific token choice.

Techniques like REINFORCE can estimate gradients through discrete sampling, but they introduce high variance. In ELECTRA's experiments, adversarial training with REINFORCE produced unstable training and worse results. The simple cooperative approach, where both networks minimize their own losses, proved more effective.

Sample Efficiency

ELECTRA's main contribution is sample efficiency: it achieves the same performance as BERT with far less compute. The original paper demonstrated this across multiple scales.

At the small scale (comparable to BERT-Small with 14M parameters), ELECTRA trained for 1/4 of BERT's training steps matched BERT's full-training performance. At the base scale (110M parameters), ELECTRA trained with 1/4 the compute exceeded BERT's performance. At the large scale (335M parameters), ELECTRA achieved new state-of-the-art results on GLUE.

Why is ELECTRA so efficient? Three factors contribute:

-

Learning from all tokens: RTD provides signal for every position, not just 15%. This roughly 6.7x increase in gradient information per batch directly translates to faster learning.

-

Easier task per token: Binary classification is simpler than vocabulary prediction. The discriminator can focus its capacity on understanding context rather than memorizing rare vocabulary items.

-

Generator bootstrapping: The small generator quickly learns to produce plausible replacements, providing meaningful training signal to the discriminator from early in training.

ELECTRA provides gradient signal at 6.7× more positions than MLM. While the per-position information content differs (15 bits for vocabulary prediction versus 1 bit for binary classification), the increased coverage more than compensates. The model receives learning signal from every token, not just the sparse masked positions.

The comparison isn't quite apples-to-apples because MLM's vocabulary-sized prediction is harder per position than RTD's binary classification. But the positions matter more than the per-position complexity: learning about context from 512 positions beats learning about vocabulary from 77 positions. The model needs to understand context to succeed at either task, and more positions means more context learning.

ELECTRA Scaling

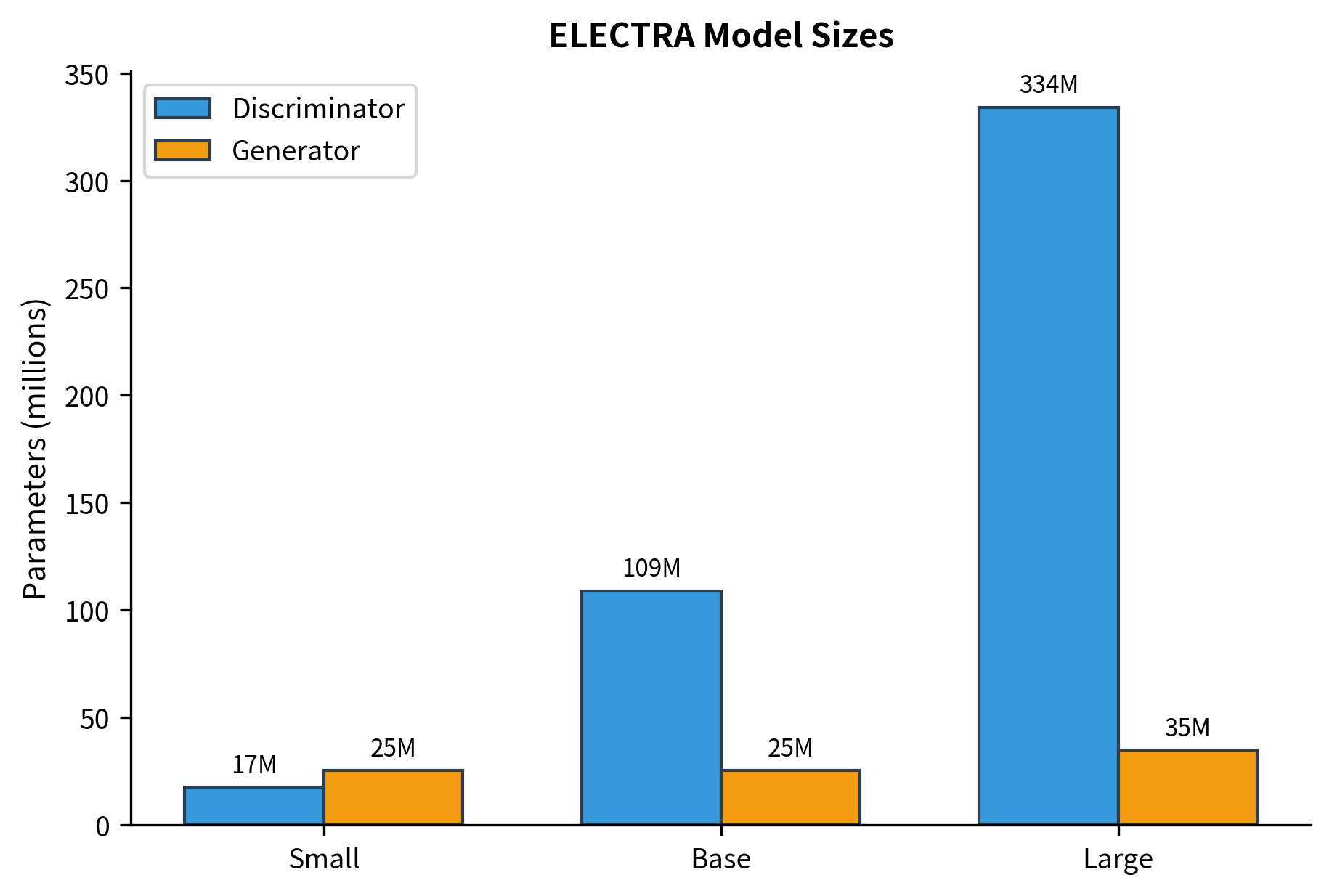

ELECTRA was released in three sizes: Small, Base, and Large. The configurations follow BERT's patterns but with the addition of a proportionally-sized generator.

The discriminator size scales from ~14M parameters (Small) to ~335M (Large), matching BERT's configurations. The generator stays fixed at 256 hidden dimensions across all sizes, contributing only ~16M additional parameters. For downstream tasks, only the discriminator parameters matter. The generator is discarded after pre-training.

Notice that the generator is always small (256 hidden size) regardless of discriminator size. This is intentional. A small generator produces imperfect replacements that are challenging but not impossible for the discriminator. The generator parameters are discarded after pre-training; only the discriminator is used for downstream tasks.

Weight Sharing

ELECTRA can optionally share embeddings between the generator and discriminator. Since both networks process the same vocabulary, their token embeddings can be identical. This reduces total parameters and ensures consistent token representations.

When the generator and discriminator have different hidden sizes (as in ELECTRA-Base and Large), sharing requires a linear projection to map between sizes:

Weight sharing introduces a subtle issue. If we backpropagate through both networks simultaneously, the shared embeddings receive gradients from both the MLM loss (via generator) and the RTD loss (via discriminator). The ELECTRA paper found this works well, with the discriminator's gradients dominating due to the higher RTD weight and the learning from all positions.

Fine-tuning ELECTRA

After pre-training, the generator is discarded. Only the discriminator is used for downstream tasks. Fine-tuning follows the same pattern as BERT: add a task-specific head and train on labeled data.

For classification tasks, the [CLS] token representation from the discriminator feeds into a classification layer:

For token-level tasks like NER or question answering, we use the full sequence output instead of just [CLS]:

One consideration for fine-tuning: ELECTRA's pre-training teaches the model to detect replaced tokens, not to understand [MASK] tokens. This means ELECTRA doesn't have the pretrain-finetune mismatch that affects BERT (where [MASK] appears in pre-training but not fine-tuning). The discriminator always sees real tokens, both during pre-training and fine-tuning.

Using Pre-trained ELECTRA

In practice, you'll load pre-trained ELECTRA models from Hugging Face rather than training from scratch:

The model outputs a 256-dimensional vector for each token (ELECTRA-Small's hidden size). The [CLS] token's representation at position 0 aggregates information from the entire sequence and is typically used for classification tasks.

For classification tasks, use the task-specific model directly:

The probabilities are close to 50/50, which is expected: the classification head was randomly initialized and hasn't been fine-tuned on any labeled data. After fine-tuning on a sentiment dataset (like SST-2), the model would produce meaningful, confident predictions.

Note that the untrained classification head produces random outputs. After fine-tuning on a sentiment dataset, the model would produce meaningful predictions.

Performance Comparison

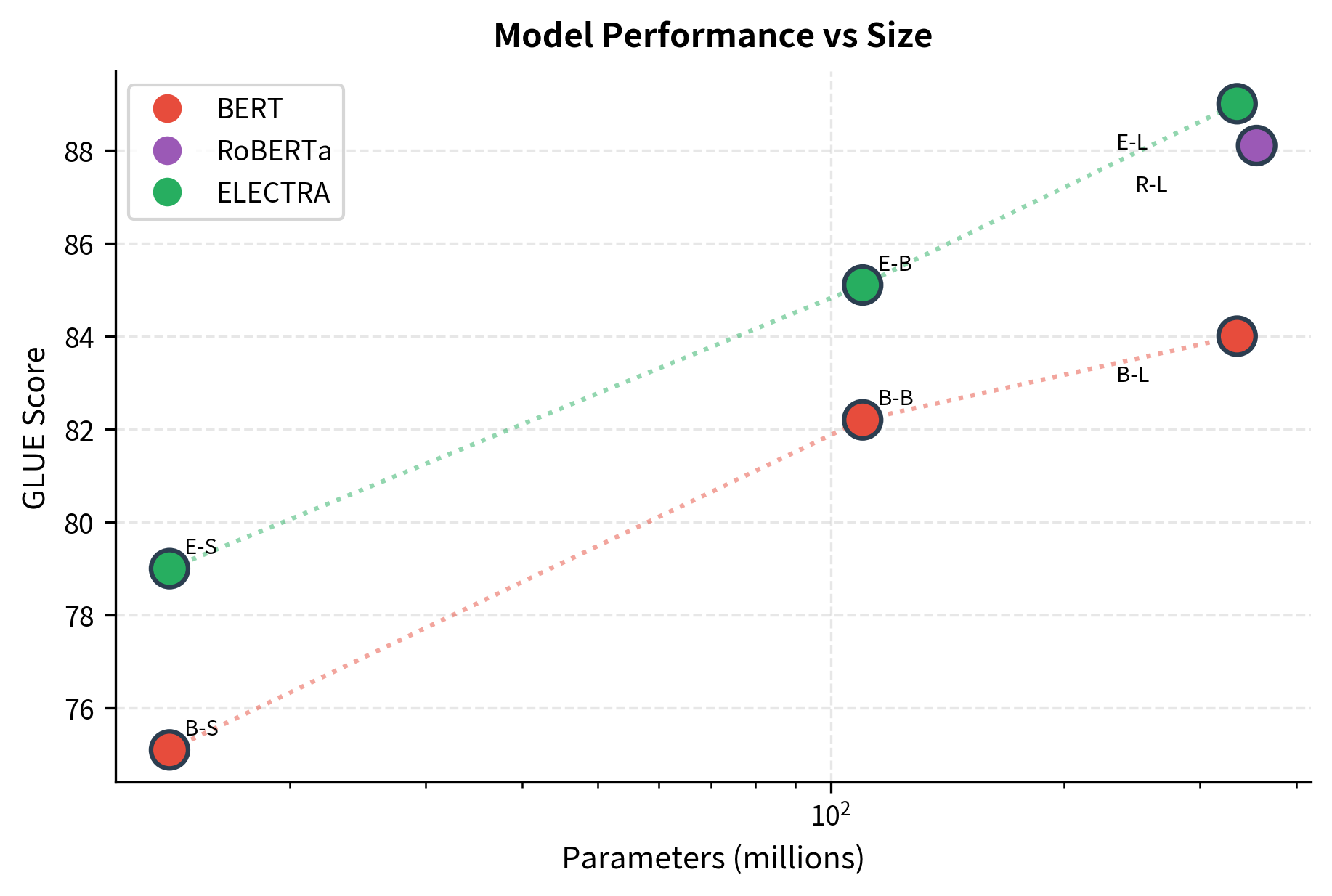

ELECTRA's results on standard benchmarks demonstrate its efficiency. Here's a comparison with BERT and RoBERTa at various scales:

The results reveal ELECTRA's remarkable efficiency. At each parameter budget, ELECTRA outperforms BERT by 3-4 points on GLUE. Most striking is ELECTRA-Small: with just 14M parameters, it achieves 79.0 on GLUE, comparable to BERT-Base at 110M parameters. This 8× parameter reduction with similar performance demonstrates that sample efficiency translates directly to model efficiency.

ELECTRA-Small outperforms BERT-Base despite having 8x fewer parameters. ELECTRA-Base exceeds RoBERTa-Base's performance. ELECTRA-Large achieves new state-of-the-art results on GLUE, exceeding RoBERTa-Large despite slightly fewer parameters.

Limitations and Impact

ELECTRA's design comes with trade-offs worth understanding.

The generator must strike a balance between too good and too bad. If the generator produces perfect replacements, the discriminator receives no learning signal because all tokens look original. If the generator is random, replacements are trivially detectable and the discriminator learns little about language. The solution of using a small generator works but adds a hyperparameter (generator size relative to discriminator) that requires tuning.

Pre-training is more complex than BERT. Two networks, two losses, sampling from the generator, and the RTD weight all need coordination. Debugging is harder because problems might arise from either network or their interaction. The implementation overhead is real, though not prohibitive.

The generator parameters are wasted after pre-training. During training, compute is split between generator and discriminator, but only the discriminator matters for downstream tasks. The ELECTRA paper argues this is worthwhile because the generator is small (1/4 to 1/3 discriminator size) and the efficiency gains outweigh the cost.

Despite these limitations, ELECTRA's impact on the field was significant. It demonstrated that MLM's inefficiency wasn't inherent to pre-training but rather a design choice that could be improved. The replaced token detection paradigm influenced subsequent models and showed that creative objective design matters as much as architecture or scale. ELECTRA remains one of the most parameter-efficient pre-training approaches, particularly valuable when compute is limited.

Key Parameters

When implementing or fine-tuning ELECTRA, these parameters matter most:

-

mask_prob (default: 0.15): Fraction of tokens masked for generator input. Follows BERT's 15% rate. Higher rates create more replaced tokens but may make generator predictions less accurate.

-

rtd_weight (default: 50): Weight on discriminator loss relative to generator loss. The high weight ensures discriminator gradients dominate shared embeddings. Lower weights may cause generator to overfit.

-

generator_size_fraction (default: 0.25 to 0.33): Generator hidden size relative to discriminator. Smaller generators produce less accurate replacements, creating harder but more varied training signal.

-

temperature (default: 1.0): Sampling temperature for generator. Higher temperatures increase diversity of replacements. Lower temperatures produce more likely tokens, which may be too easy to detect.

-

learning_rate (default: 2e-4 for ELECTRA-Base): Both networks use the same learning rate. The standard BERT learning rate works well.

-

weight_sharing (default: True for embeddings): Whether generator and discriminator share token embeddings. Reduces parameters and ensures consistent token representations.

-

max_seq_length (default: 512): Maximum sequence length. ELECTRA uses full 512 throughout training, unlike BERT's phased approach.

Summary

ELECTRA reimagines pre-training by replacing masked language modeling with replaced token detection:

-

Two-network architecture: A small generator creates plausible token replacements for masked positions. A larger discriminator learns to detect which tokens were swapped.

-

Sample efficiency: By learning from every token position (not just 15% masked ones), ELECTRA achieves BERT's performance with 1/4 the compute. Given equal resources, it significantly exceeds BERT.

-

Cooperative training: Unlike GANs, both networks minimize their own losses rather than competing. This avoids gradient estimation problems for discrete text.

-

Generator size matters: The generator should be small enough to make mistakes but good enough for those mistakes to be plausible. This sweet spot provides optimal training signal.

-

Fine-tuning simplicity: Only the discriminator is used for downstream tasks. Fine-tuning follows the standard BERT pattern with no

[MASK]token mismatch. -

State-of-the-art efficiency: ELECTRA-Small outperforms BERT-Base despite 8x fewer parameters. ELECTRA-Large achieves the best GLUE results among comparably-sized models.

ELECTRA demonstrates that pre-training objective design matters as much as architecture scale. By learning from every token, it extracts maximum value from each training batch, making it particularly valuable when compute is limited.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about ELECTRA's efficient pre-training approach.

Comments