Master the mechanics of autoregressive generation in transformers, including the generation loop, KV caching for efficiency, stopping criteria, and speed optimizations for production deployment.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Autoregressive Generation

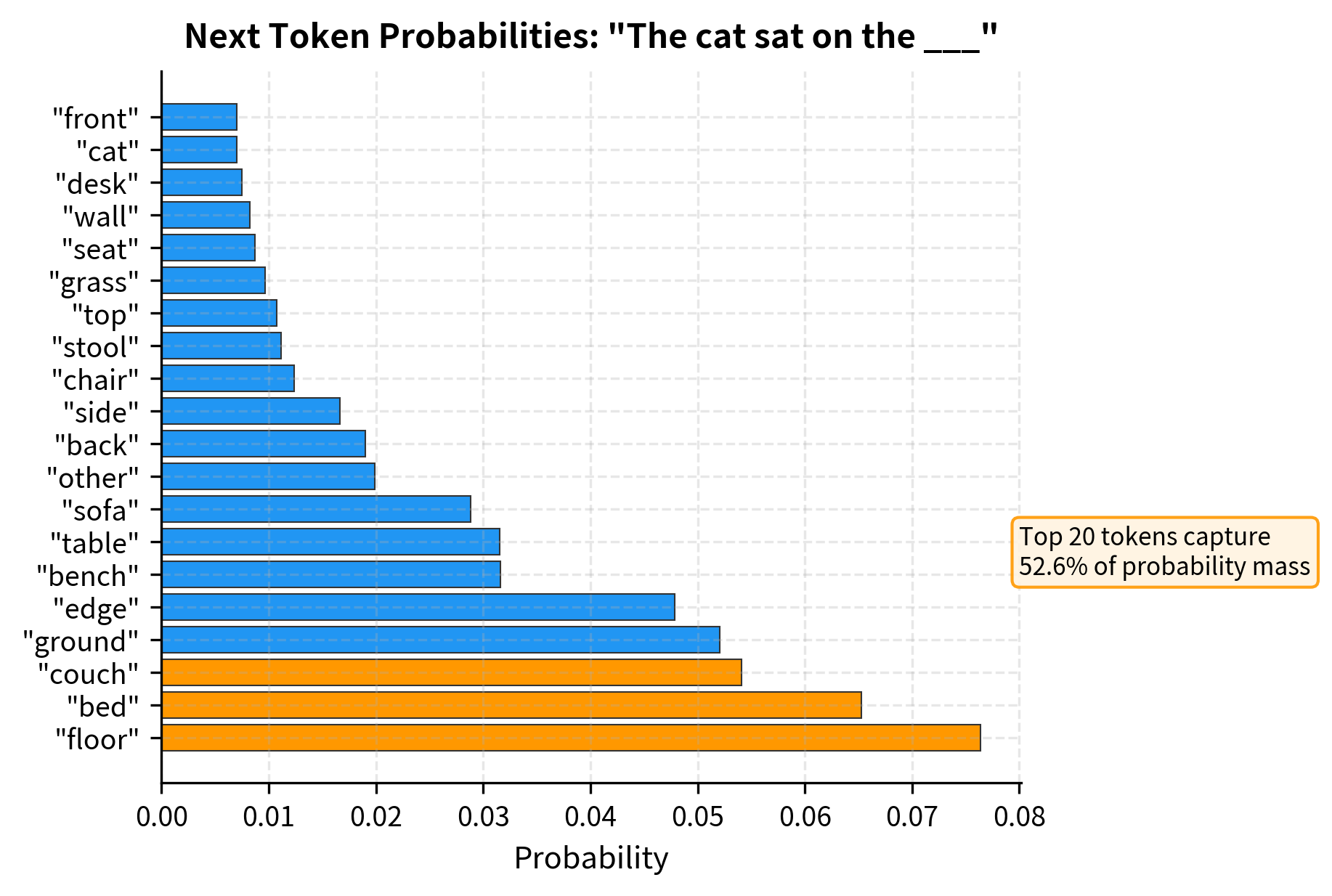

When you ask a language model to complete the sentence "The cat sat on the", it doesn't produce the entire response at once. Instead, it generates text one token at a time, each new token conditioned on all the tokens that came before. This process, called autoregressive generation, is the fundamental mechanism by which decoder-only transformers like GPT produce coherent, contextually appropriate text.

Understanding autoregressive generation is essential for working with modern language models. The process seems simple on the surface: predict the next token, append it to the sequence, and repeat. But underneath this simple loop lies a computational challenge that has driven significant research into efficiency optimizations. The key insight is that naive generation would recompute the same attention calculations repeatedly, wasting enormous amounts of compute. The solution, key-value caching, transforms generation from quadratically expensive to linearly efficient.

This chapter explores the mechanics of autoregressive generation in detail. We'll implement the generation loop from scratch, understand why KV caching is crucial for practical deployment, examine stopping criteria that determine when generation ends, and explore techniques for optimizing generation speed. By the end, you'll understand not just how to call a generation function, but how generation actually works inside the model.

The Generation Procedure

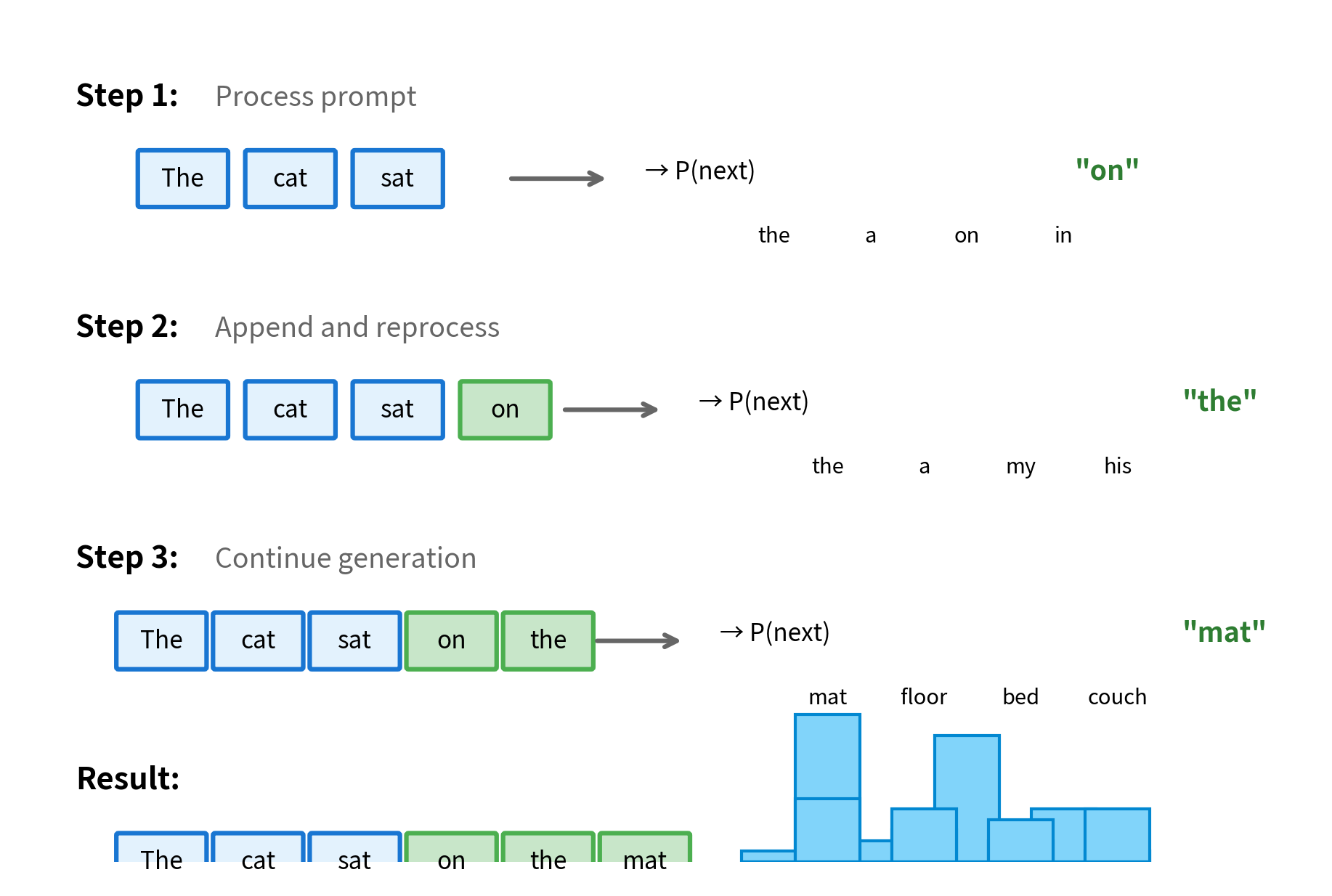

Autoregressive generation follows a straightforward principle: at each step, the model predicts a probability distribution over possible next tokens, selects one token from that distribution, appends it to the sequence, and repeats until some stopping condition is met.

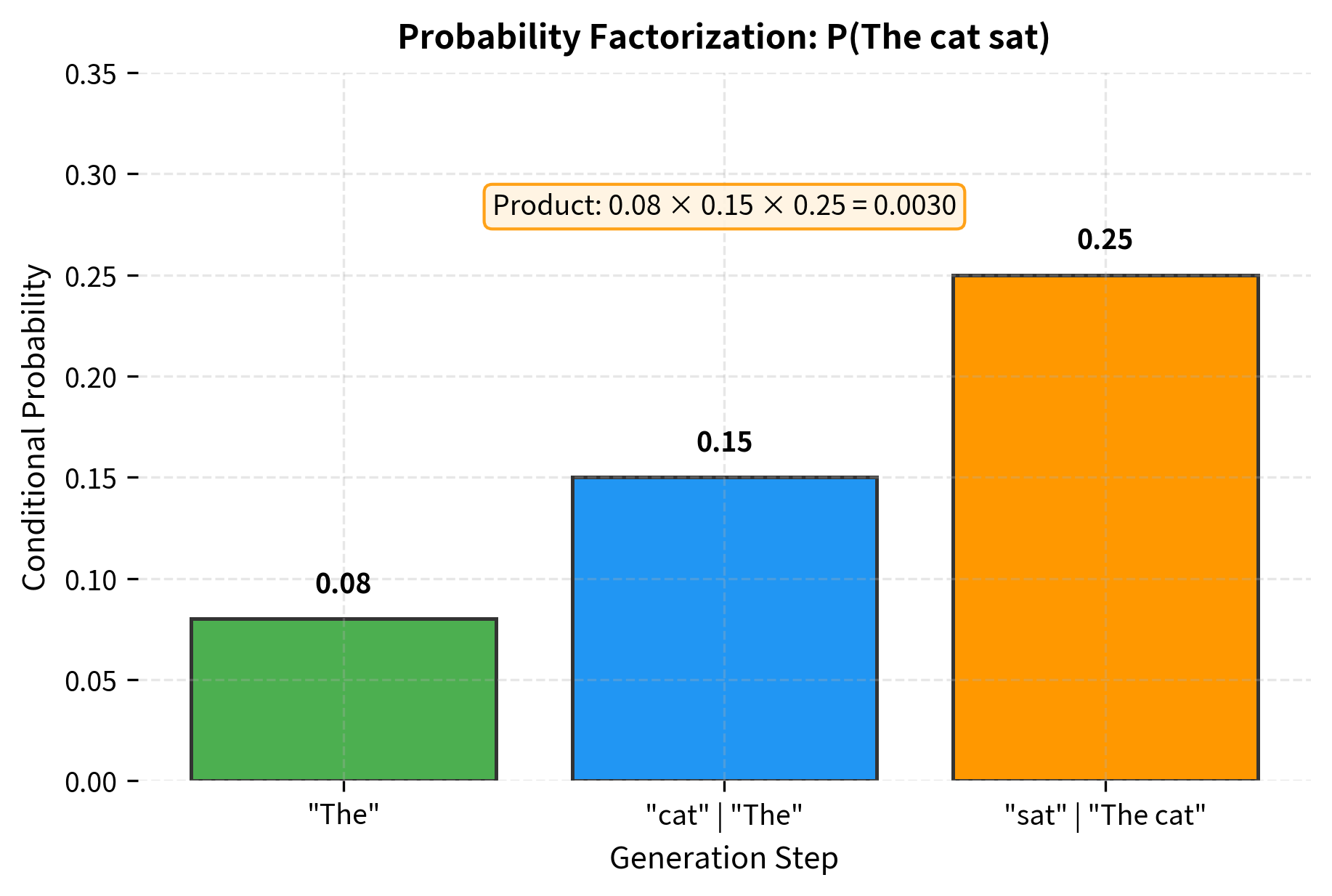

Autoregressive generation produces sequences token-by-token, where each new token is conditioned on all previously generated tokens. The probability of generating a complete sequence factorizes as , meaning we multiply together the probability of each token given everything that came before it.

The process begins with a prompt, which is a sequence of tokens provided by the user. The model processes this prompt to produce hidden states, then uses the final hidden state to predict the first generated token. This token is appended to the prompt, the model processes the extended sequence, and the cycle continues.

This implementation reveals several important aspects of generation. First, the model produces logits (unnormalized log-probabilities) for every position in the vocabulary at once. We only use the logits at the final position since that's where the next token prediction happens. Second, greedy decoding, which always selects the most probable token, is deterministic: the same prompt always produces the same output. Third, the loop continues until we either reach max_new_tokens or generate an end-of-sequence token.

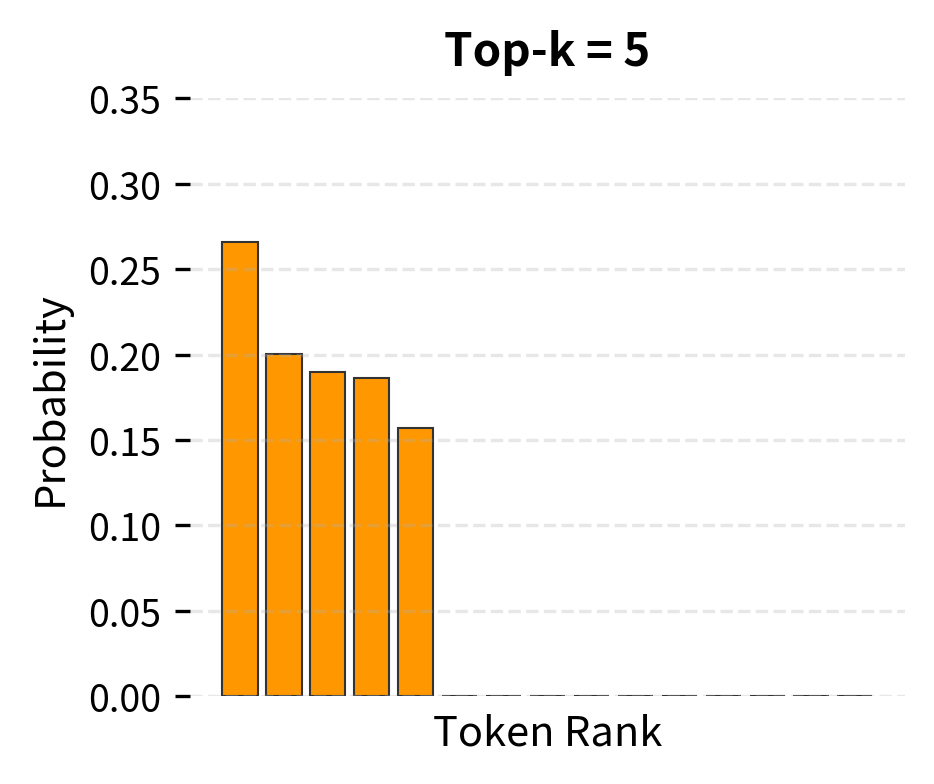

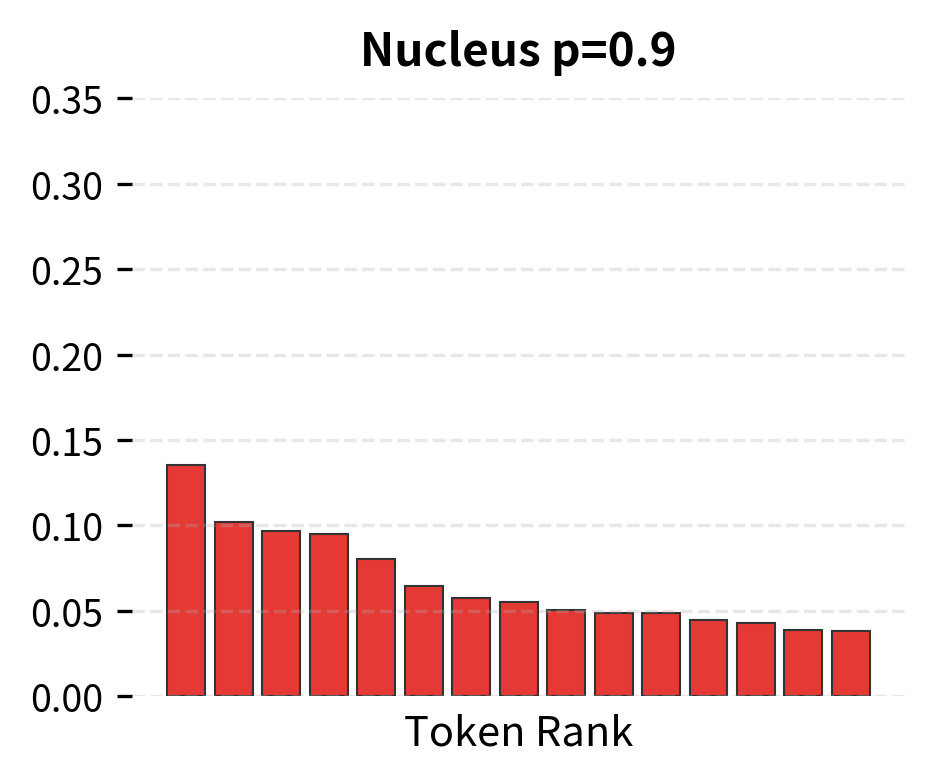

The generated continuation flows naturally from the prompt, demonstrating that the model has learned meaningful language patterns. Notice how each word follows logically from the previous context. Greedy decoding often produces repetitive or generic text because it always takes the safe, high-probability path. We'll explore more sophisticated sampling strategies in subsequent chapters on temperature, top-k sampling, and nucleus sampling. For now, the key insight is that all generation strategies share the same underlying loop: predict, select, append, repeat.

The Generation Loop in Detail

Let's trace through exactly what happens at each step of generation. Consider a simple 4-token vocabulary and a prompt of 3 tokens:

At each step, the model must process the entire sequence to maintain the correct attention patterns. The attention mechanism at position computes weighted sums over all positions , so earlier tokens influence later predictions. This creates a computational challenge: as the sequence grows, each forward pass becomes more expensive.

Mathematical Formulation

The generation loop we've been exploring raises a fundamental question: how do we assign a probability to an entire sequence of tokens? Consider the sentence "The cat sat on the mat". It would be impractical to maintain a probability table for every possible sentence, as natural language allows infinitely many valid sequences. Instead, we need a way to decompose sequence probability into manageable pieces.

From Intuition to the Chain Rule

Think about how you might estimate the likelihood of a sentence. You wouldn't evaluate it as a monolithic unit. Instead, you'd naturally consider: How likely is "The" as an opening word? Given that we started with "The", how likely is "cat" to follow? Given "The cat", how likely is "sat"? This intuitive approach of building probability step by step is exactly what autoregressive models formalize.

The mathematical foundation comes from the chain rule of probability, which states that any joint probability can be decomposed into a product of conditional probabilities. For a sequence of tokens, this gives us the autoregressive factorization:

where:

- : the token at position in the sequence

- : the total sequence length (number of tokens)

- : the conditional probability of token given all preceding tokens, often written as for brevity

- : the product over all positions from 1 to

This factorization is powerful because it transforms the impossible task of modeling all possible sentences into a tractable one: we only need to model what comes next given what we've seen so far. Each factor in the product corresponds to exactly one step of the generation loop.

A Concrete Example

Let's trace through the factorization for our example sentence "The cat sat":

-

First token: asks how likely "The" is as an opening. Common sentence starters like "The", "A", "I" receive high probability.

-

Second token: asks what noun is likely after "The". Words like "cat", "dog", "man", "house" all receive some probability mass.

-

Third token: asks what action a cat might perform. "sat", "jumped", "ran", "slept" become likely candidates.

The full sequence probability is the product: . If any factor is near zero, the entire product collapses, reflecting that an unlikely transition makes the whole sequence improbable.

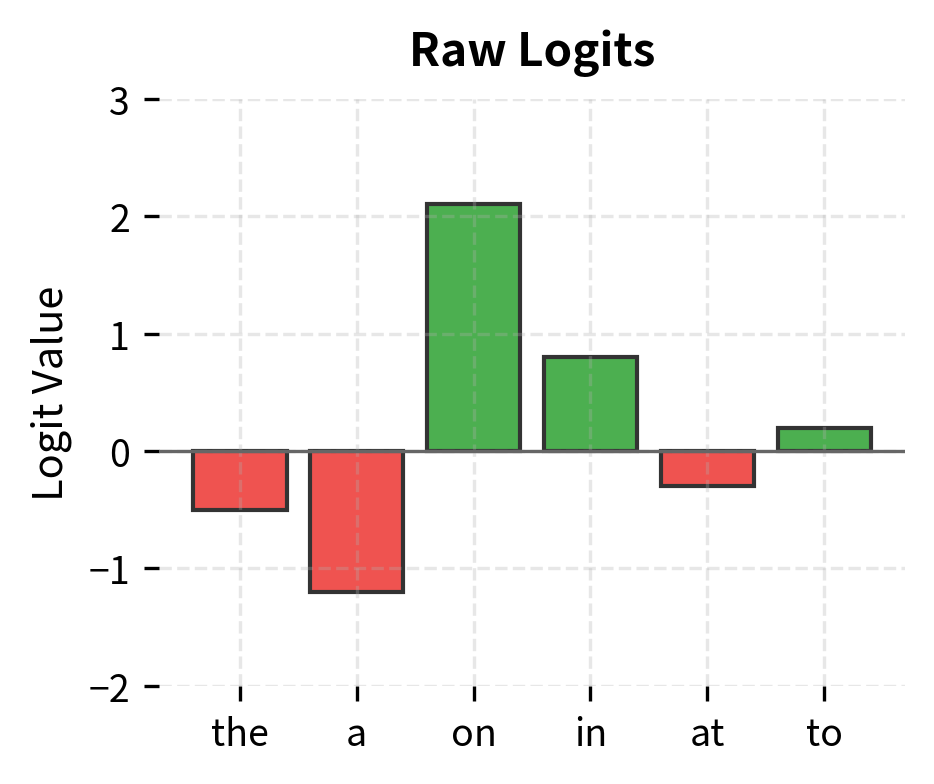

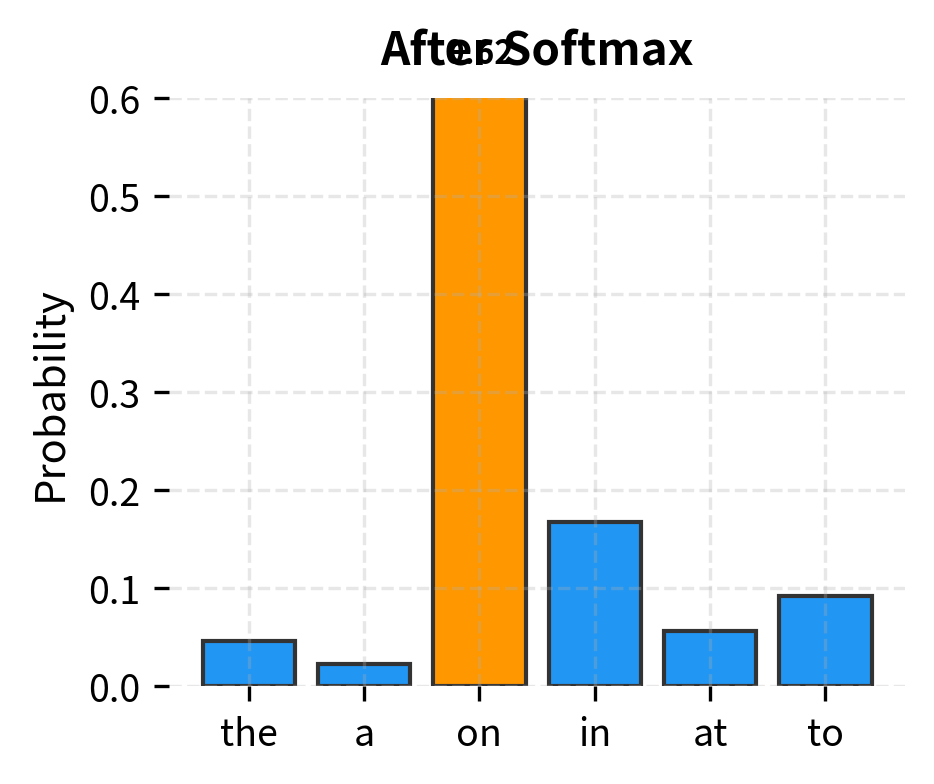

From Hidden States to Probabilities

Now we need to understand how the model actually computes each conditional probability . This happens in two stages:

-

Encode the context: The transformer processes all tokens to produce a hidden state that summarizes the relevant context.

-

Project to vocabulary: A linear layer maps this hidden state to a score for every token in the vocabulary, then softmax converts these scores to probabilities.

The formula for this computation is:

where:

- : the hidden state vector at position from the final transformer layer, where is the hidden dimension (e.g., 768 for GPT-2 Small). This vector encodes everything the model "knows" about the context so far.

- : the language modeling head weight matrix that projects from hidden dimension to vocabulary size . Each row of this matrix can be thought of as a "template" for one vocabulary token.

- : the bias term (often zero or absent in modern implementations), which captures token-independent frequency preferences.

- : the probability assigned to token after normalization.

The product computes a score (logit) for each vocabulary token by measuring how similar the current context representation is to each token's template. Higher scores indicate more likely next tokens. The softmax function then performs two crucial operations:

- Exponentiation () ensures all values become positive

- Normalization (dividing by the sum) ensures probabilities sum to 1

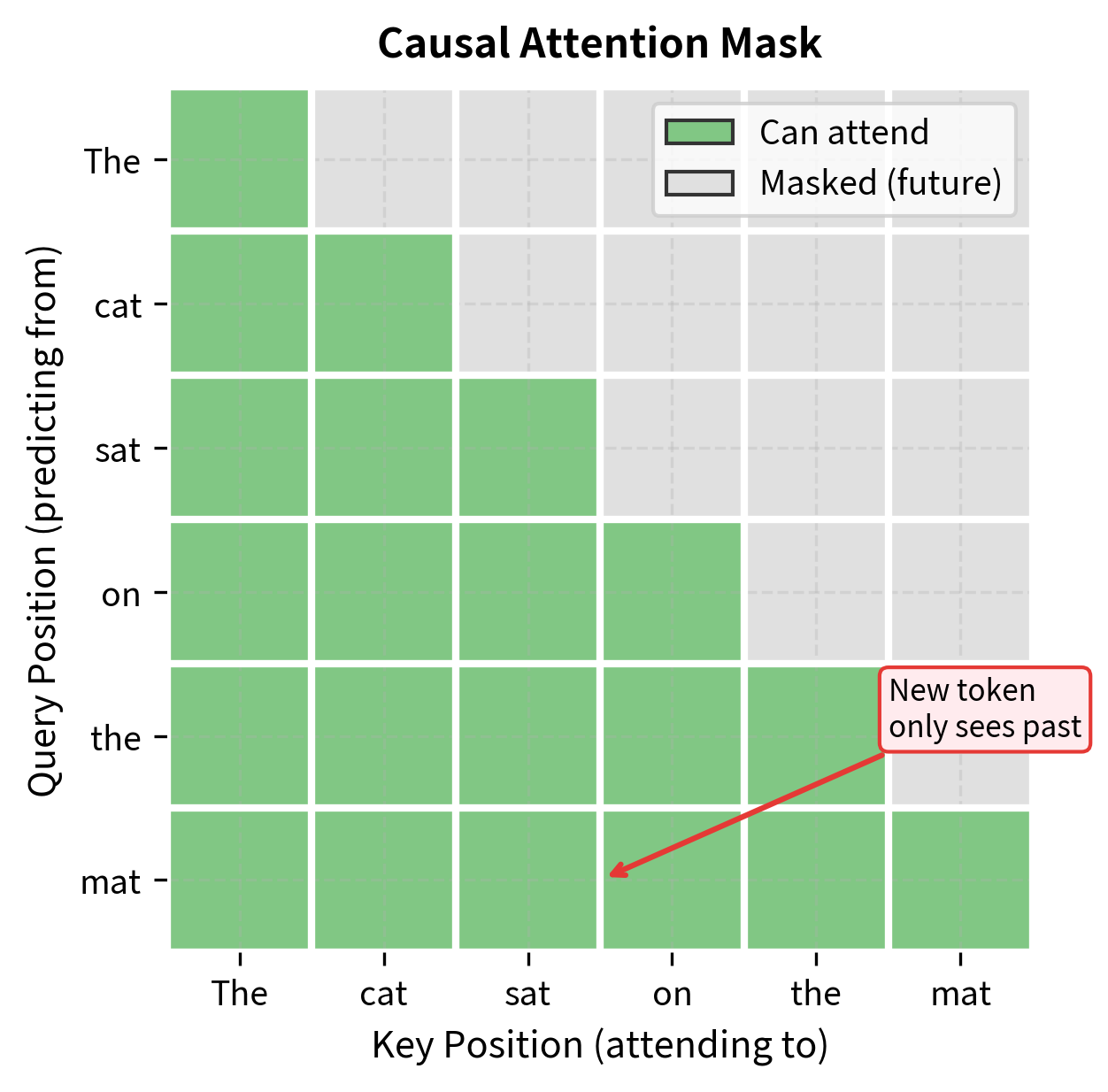

Why Generation Must Be Sequential

This mathematical structure reveals a fundamental constraint: we cannot parallelize generation across positions. To compute , the model must know tokens , because the transformer's causal attention mask prevents each position from seeing future tokens.

Concretely, if we want to predict the 10th token:

- We need , the hidden state at position 10

- Computing requires attention over positions 1 through 9

- But positions 1 through 9 must contain actual tokens, not placeholders

- Therefore, we must have already generated tokens 1 through 9

This sequential dependency is what makes autoregressive generation inherently step-by-step. Unlike tasks like classification where we process the entire input in parallel, generation must proceed one token at a time, with each new token depending on all previous decisions.

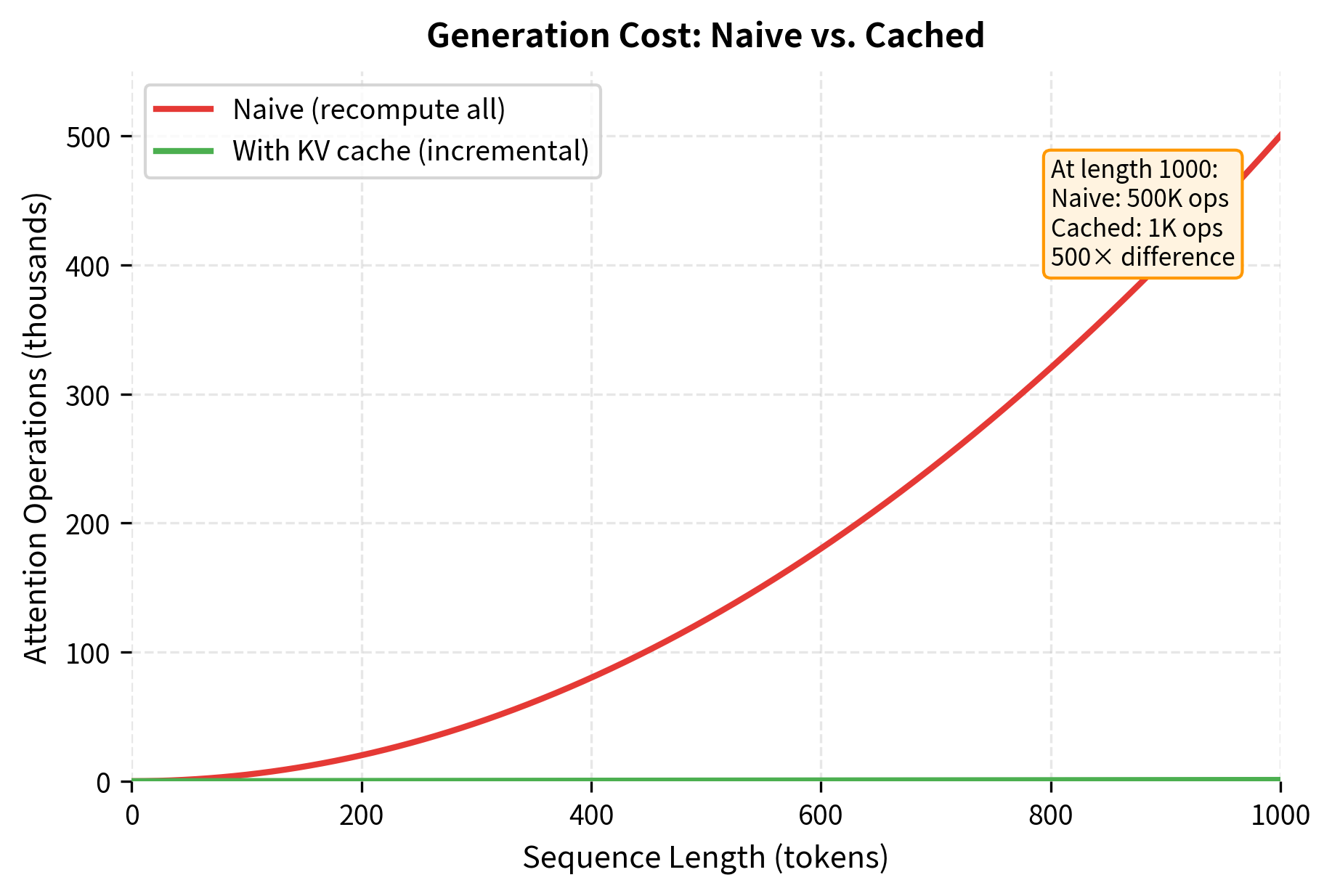

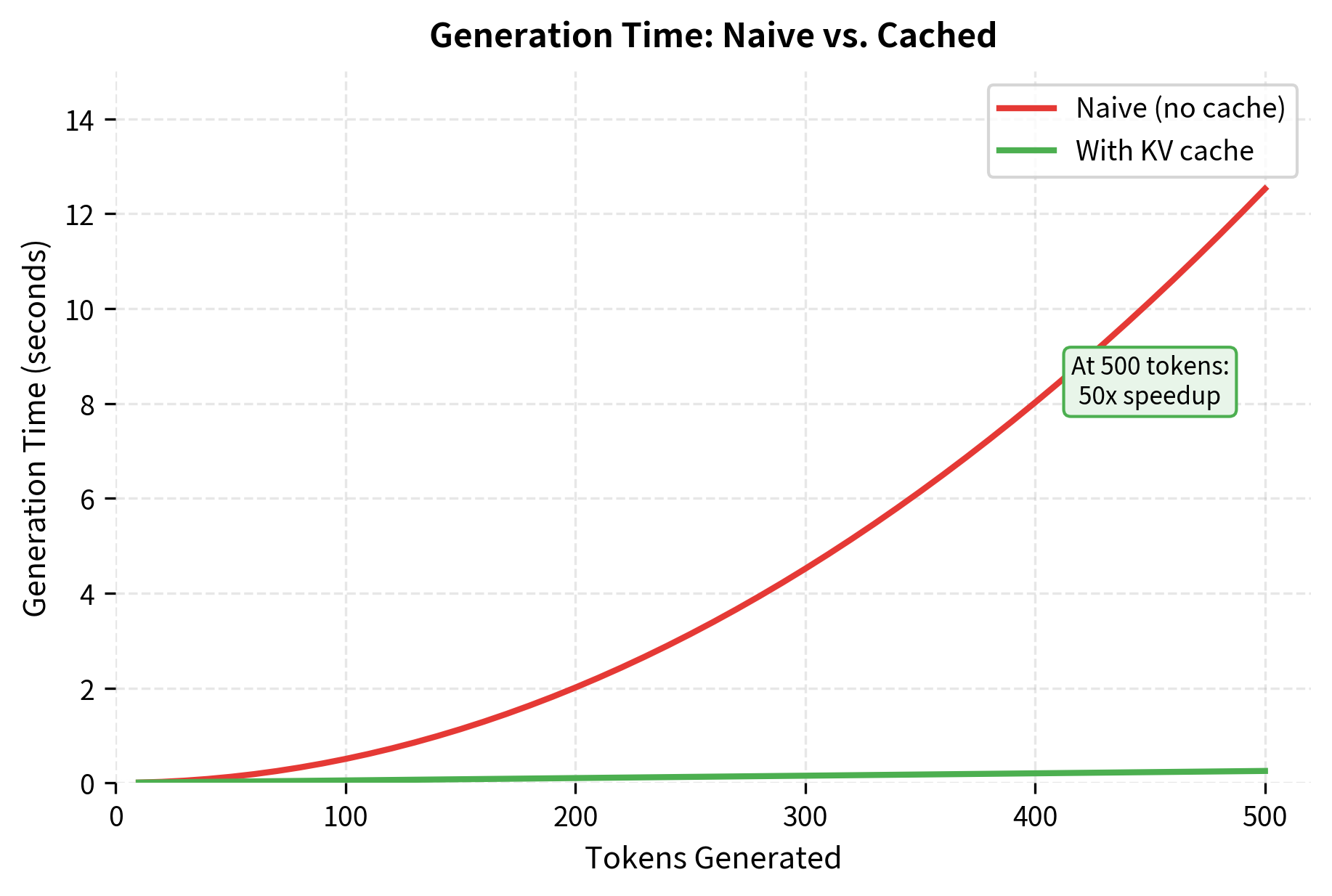

Why Naive Generation is Expensive

Consider generating 100 tokens after a 50-token prompt. With naive generation, each step requires a full forward pass through the model. The first generated token requires processing 50 tokens. The second requires processing 51 tokens. The hundredth requires processing 149 tokens.

The total computation scales quadratically with sequence length because attention at each position must attend to all previous positions. To see why, consider that at generation step , we must compute attention over a sequence of length . The total number of attention operations across all generation steps is:

where:

- : the total number of tokens generated

- : the sum of sequence lengths processed at each step (1 + 2 + 3 + ... + T)

- : the closed-form solution for this arithmetic series

- : big-O notation indicating quadratic growth with sequence length

This quadratic relationship means that generating 1000 tokens requires roughly 1,000,000 attention operations proportionally, while generating just 100 tokens requires only about 10,000. The cost grows much faster than the output length.

For practical deployments where latency matters, this quadratic scaling is unacceptable. Generating a single response could take tens of seconds even on powerful hardware. The solution is to cache intermediate computations and reuse them across generation steps.

Key-Value Caching

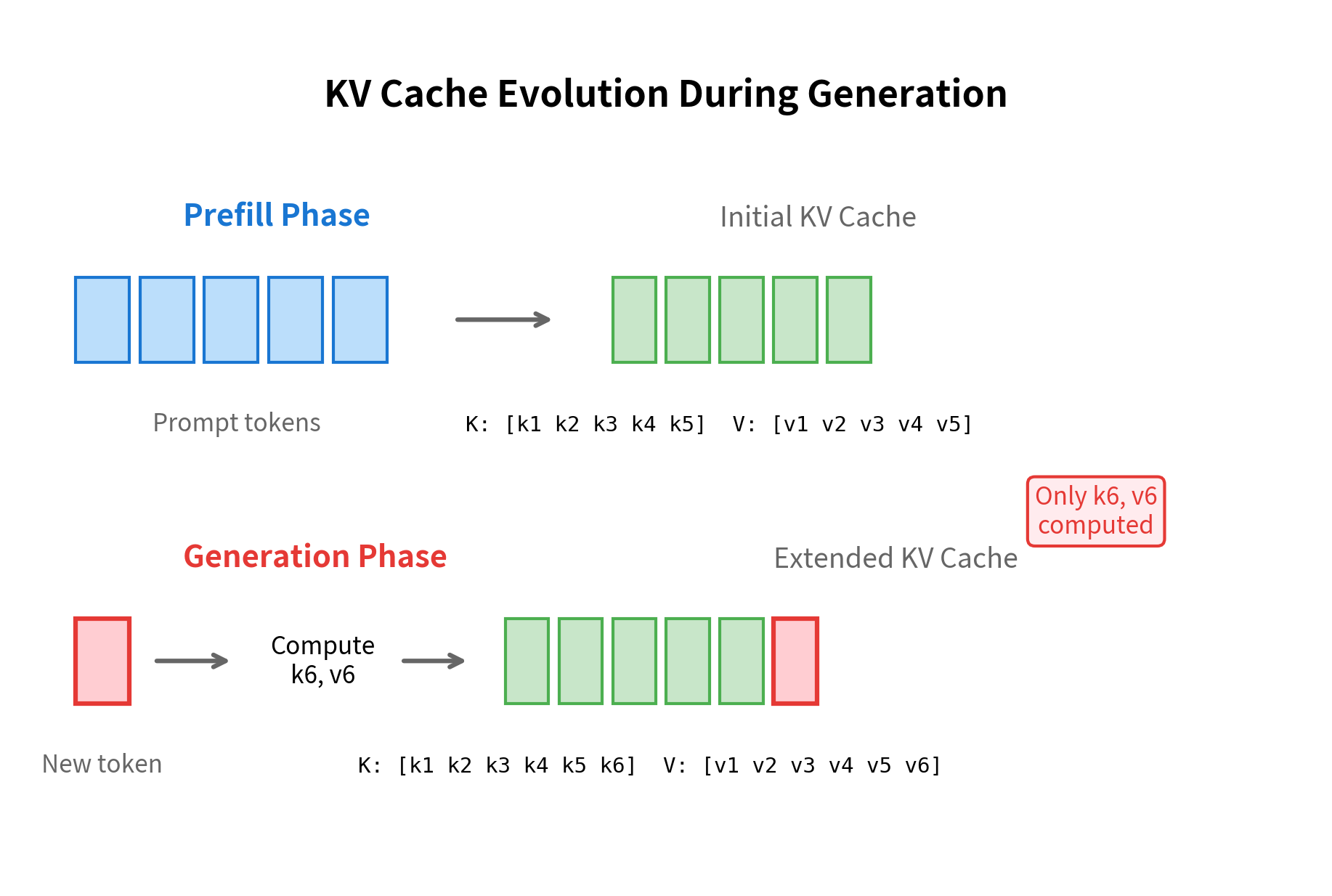

The key insight behind KV caching is that during autoregressive generation, the attention keys and values for positions 1 through don't change when we generate token . Only the new token at position introduces new keys and values. Instead of recomputing everything, we cache the keys and values from previous positions and only compute the new entries.

The KV cache stores the key and value projections from each attention layer for all previously processed tokens. During generation, only the new token's keys and values are computed and appended to the cache, avoiding redundant computation.

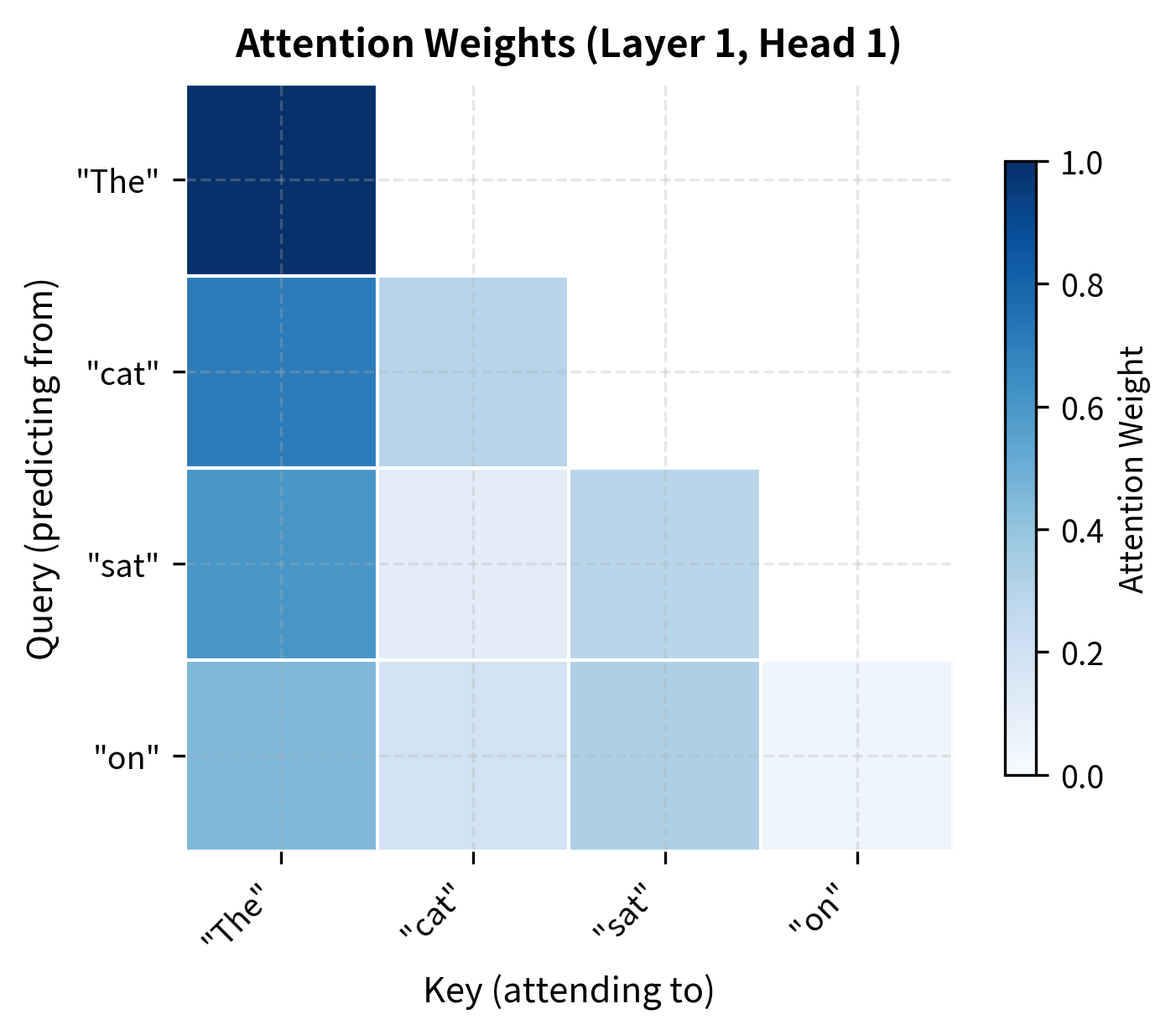

How Attention Works Without Caching

To understand why KV caching helps, we first need to understand what happens in standard attention. In multi-head attention, for a sequence of length , we compute queries, keys, and values from the input, then use them to compute a weighted sum:

where:

- : the query matrix containing a query vector for each of the positions

- : the key matrix containing a key vector for each position

- : the value matrix containing a value vector for each position

- : the dimension of each key (and query) vector, typically 64 in GPT-2

- : the attention score matrix where entry measures how much position attends to position

- : a scaling factor that prevents the dot products from growing too large, which would push softmax into regions with vanishing gradients

- : normalizes each row of the attention scores to sum to 1, creating attention weights

The formula works in three steps: (1) compute attention scores by taking dot products between queries and keys, (2) normalize scores with softmax to get attention weights, and (3) compute weighted sums of values using those weights.

During generation, we actually only need the query at the last position to predict the next token. But without caching, we must recompute the entire and matrices at every step because the attention mechanism requires all previous keys and values to compute the softmax normalization correctly.

How Attention Works With Caching

With KV caching, we maintain running matrices and that accumulate the keys and values for all tokens processed so far. When generating token :

- Compute only , , for the new token (a single vector each)

- Append to and to (cache grows by one row)

- Compute attention using (single query) against the full cache

The attention computation for the new token becomes:

where:

- : the query vector for the single new token at position

- : the cached key matrix containing keys for all positions seen so far

- : the cached value matrix containing values for all positions

- : a single row of attention scores (the new token attending to all previous positions)

- : the same scaling factor as before

The key insight is that produces just a single row of attention scores rather than a full matrix. We compute dot products instead of , reducing the per-step computation from to . Over the full generation of tokens, this changes the total cost from to , a dramatic improvement for long sequences.

The cache has grown from 10 to 11 positions after processing a single new token. Notice that the input to this step was just one token, not the entire sequence of 11. This is the efficiency gain: we only compute the new keys and values while reusing all previously cached entries.

The shapes reveal the broader efficiency principle. After the initial prompt, each generation step only processes a single token, but the cache grows to include all previous positions. The attention computation uses the single-token query against the full key cache.

Memory Implications

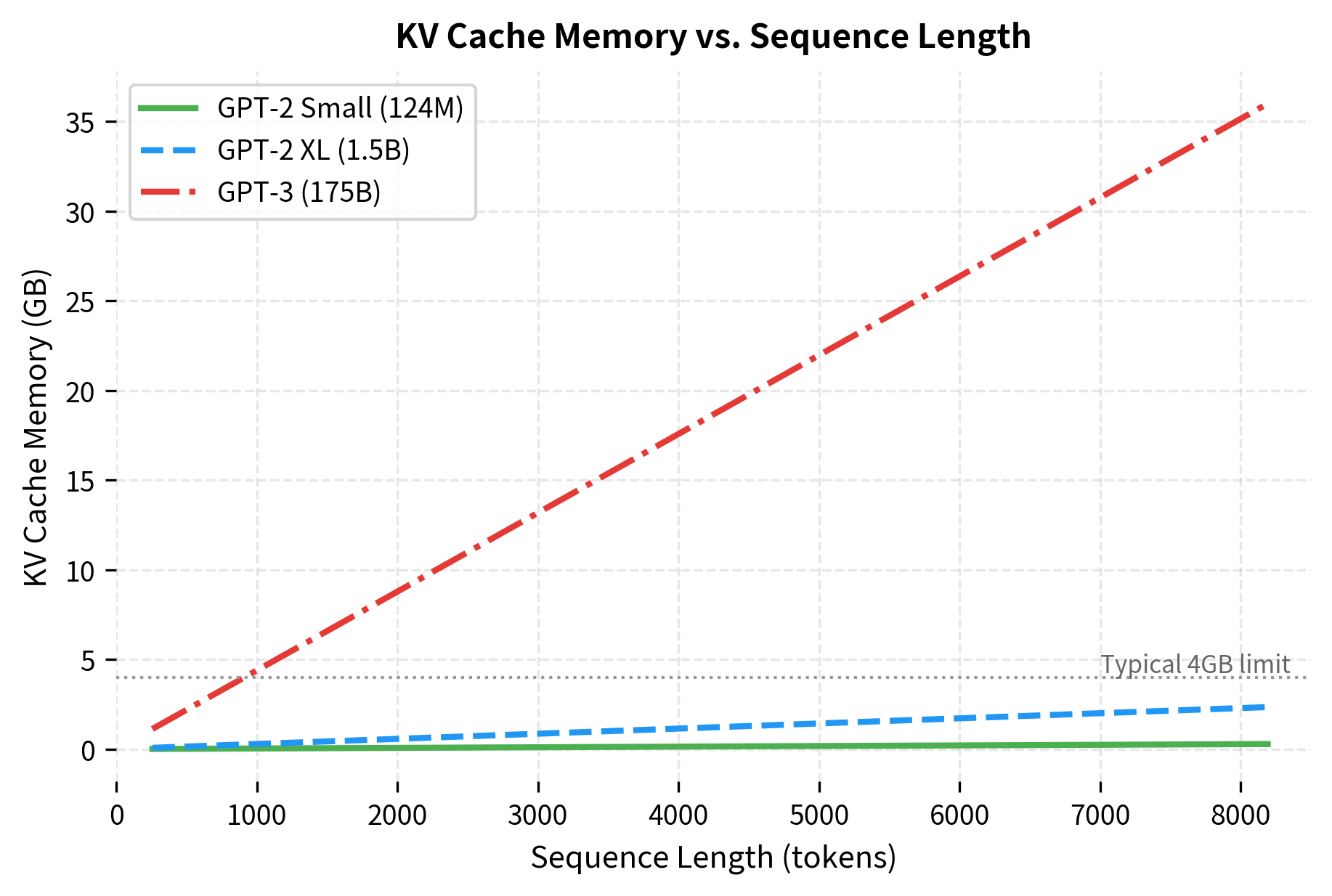

KV caching trades memory for computation. We gain speed by storing intermediate results, but this requires additional GPU memory that grows with sequence length. Understanding this trade-off is essential for deploying models with long context windows.

For a model with layers, attention heads per layer, head dimension , batch size , and sequence length , the total cache memory requirement is:

where:

- : accounts for storing both keys and values (two tensors per layer)

- : number of transformer layers (each layer has its own cache)

- : batch size (number of sequences being generated in parallel)

- : number of attention heads per layer

- : dimension of each head (typically )

- : current sequence length (grows during generation)

- : bytes per element (4 for float32, 2 for float16/bfloat16)

The product equals the model's hidden dimension , so we can also write this as . The key insight is that cache memory grows linearly with both model depth and sequence length .

For GPT-2 Small (12 layers, 12 heads, 64-dimensional heads, giving ) with float16 precision:

These numbers reveal a key practical constraint. For GPT-2 Small, cache requirements remain modest even at 8K tokens. But for production-scale models like GPT-3, the cache alone consumes multiple gigabytes. When serving many concurrent users, cache memory often becomes the limiting factor before model weights.

For very long sequences or large batch sizes, the KV cache can become a significant memory bottleneck. This has motivated research into cache compression, sparse attention patterns, and other memory-efficient generation techniques.

Implementation with Full Model

Let's implement efficient generation with KV caching using the Hugging Face transformers library, which handles cache management automatically:

The cached version runs faster because it avoids recomputing keys and values for the entire sequence at each step. For this short 30-token generation, the speedup may appear modest, but it grows substantially with sequence length. At 1000 tokens, the difference becomes orders of magnitude.

The speedup from KV caching becomes more pronounced with longer sequences. For production deployments, cached generation is essential for acceptable latency.

Stopping Criteria

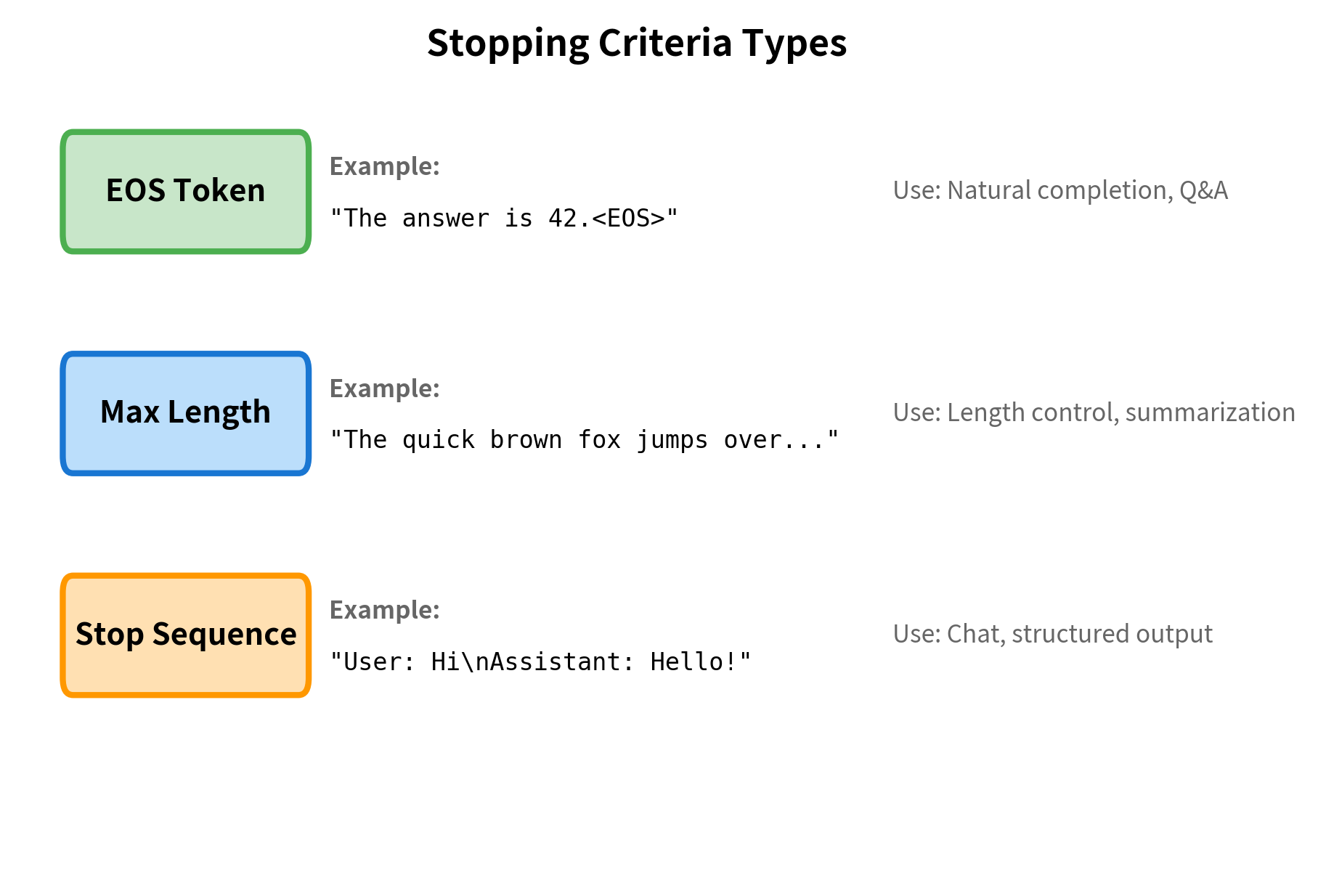

Generation must stop at some point. Without explicit stopping criteria, the model would continue generating tokens indefinitely (or until hitting a maximum length). Several strategies determine when to halt generation.

End-of-Sequence Token

The most common stopping criterion is the end-of-sequence (EOS) token. During training, sequences end with a special token that signals completion. When the model generates this token, we stop:

The EOS token works well for tasks with natural endings, like completing a sentence or answering a question. However, some prompts don't have clear endpoints, and the model may never generate EOS.

Maximum Length

A hard maximum length prevents runaway generation:

Stop Sequences

For specific applications, we might want to stop when certain text patterns appear. This is common in chat applications where we stop at user turn markers:

The generation stopped as soon as it encountered one of our specified patterns. This is particularly useful for structured outputs where you know the format in advance, such as generating exactly three items in a list or stopping at the end of an assistant's turn in a conversation.

Multiple Stopping Criteria

In practice, we often combine multiple criteria. The Hugging Face library supports this through StoppingCriteria objects:

Generation Speed Optimization

Beyond KV caching, several techniques can accelerate generation. These optimizations are crucial for production deployments where latency directly impacts user experience.

Batch Processing

Processing multiple prompts simultaneously amortizes the overhead of loading model weights. The attention computation is parallelized across the batch dimension:

Batch generation processes all four prompts faster than running them one at a time. The speedup comes from amortizing the model loading overhead and parallelizing the attention computations across the batch dimension. This makes batching essential for high-throughput serving scenarios.

Mixed Precision

Using half-precision (float16) or brain floating point (bfloat16) reduces memory bandwidth and enables faster computation on modern GPUs:

The memory savings from half precision are substantial:

Cutting the model precision in half directly halves the memory footprint, allowing larger batch sizes or longer sequences to fit in the same GPU memory. On modern GPUs with tensor cores, float16 operations are also faster than float32, providing both memory and speed benefits.

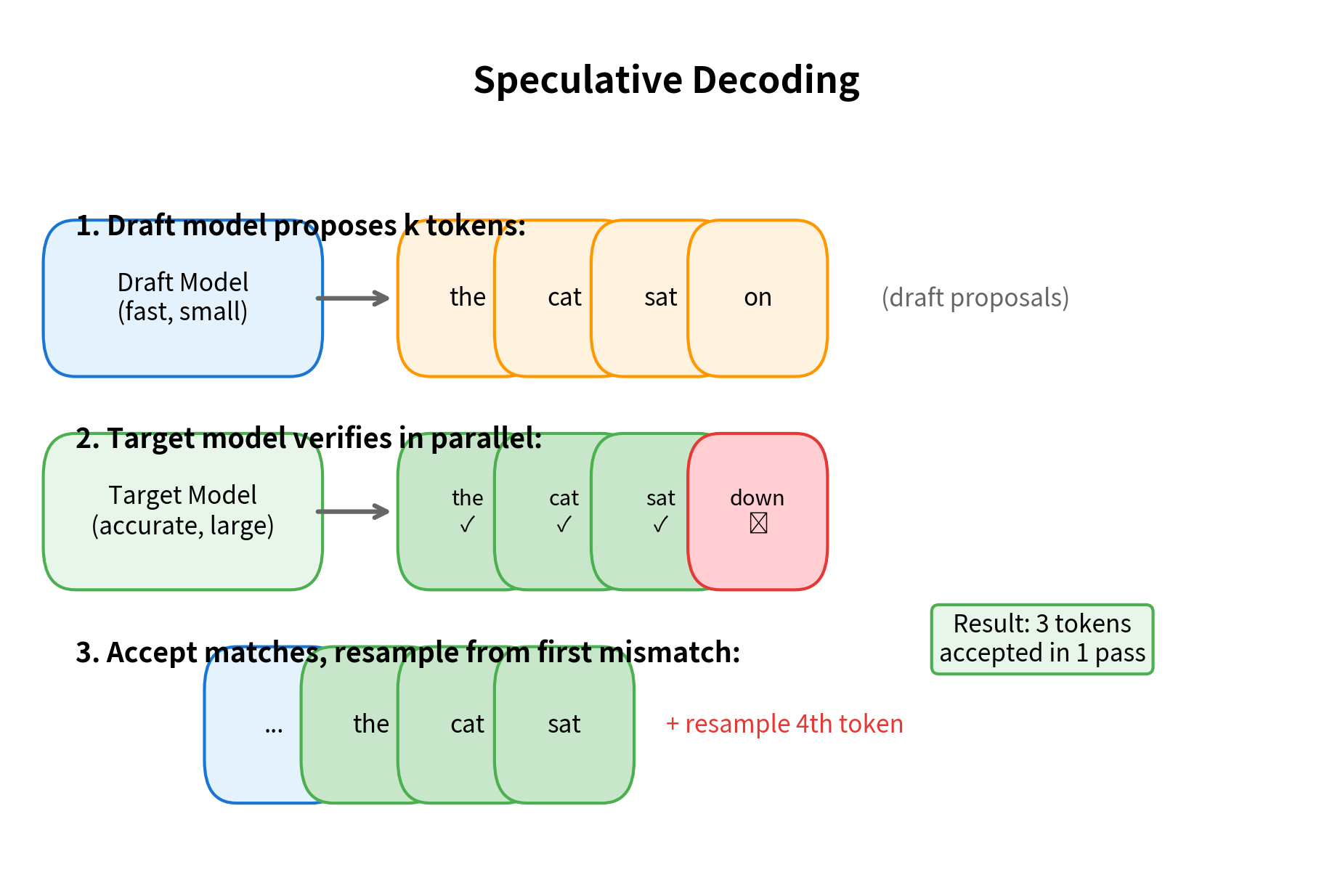

Speculative Decoding

Speculative decoding uses a smaller "draft" model to propose multiple tokens, then verifies them with the larger model in a single forward pass. When predictions align, multiple tokens are accepted at once:

The effectiveness of speculative decoding depends on how well the draft model predicts the target model's outputs. When they agree frequently, significant speedups are possible. When they disagree often, the overhead of running two models provides little benefit.

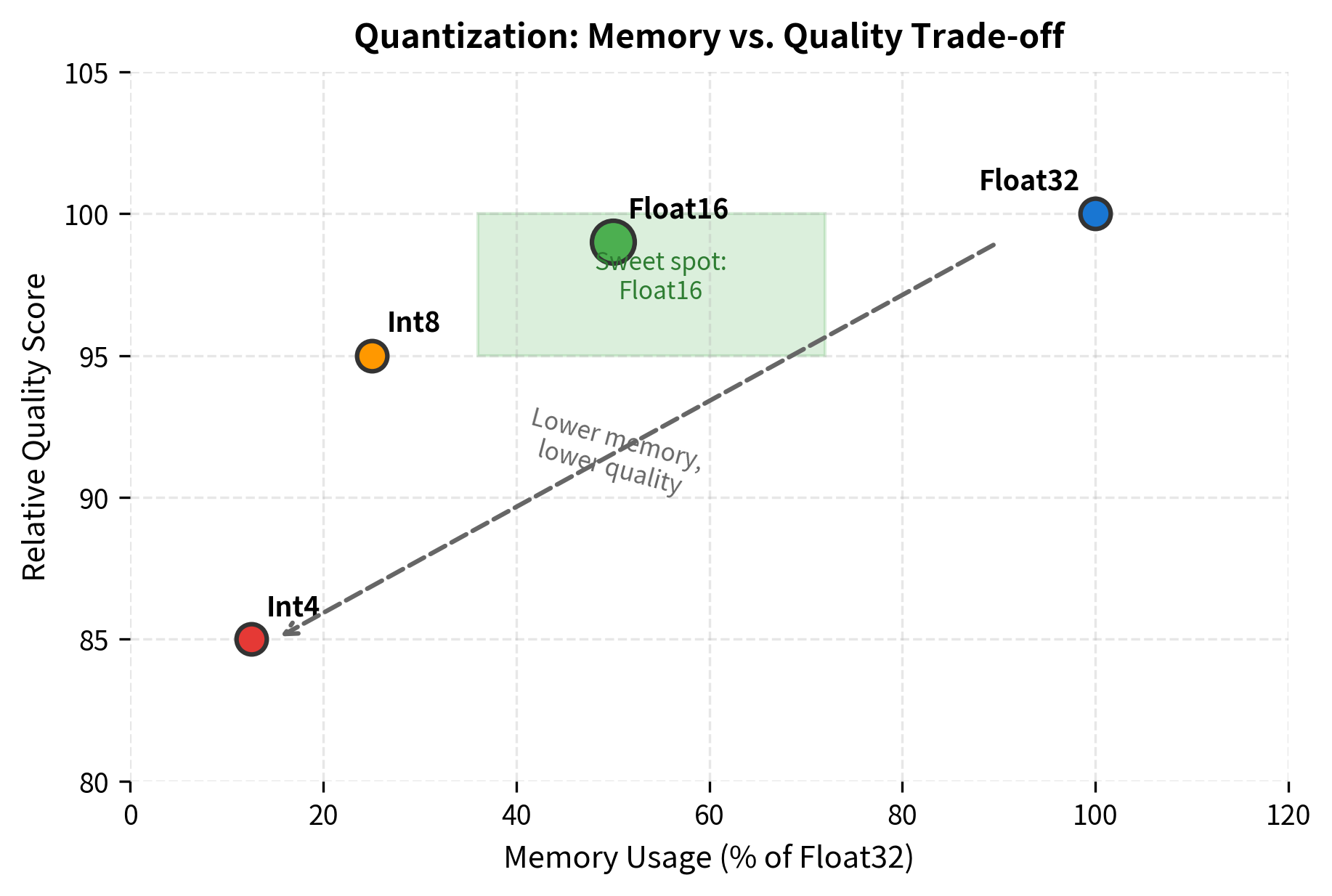

Quantization

Reducing model precision further with quantization (8-bit, 4-bit, or even lower) enables faster inference with reduced memory:

The trade-off between precision and quality is application-dependent. For many tasks, float16 provides virtually identical results to float32. Int8 quantization typically works well for inference with minimal degradation. Int4 can cause noticeable quality loss but enables running much larger models on limited hardware.

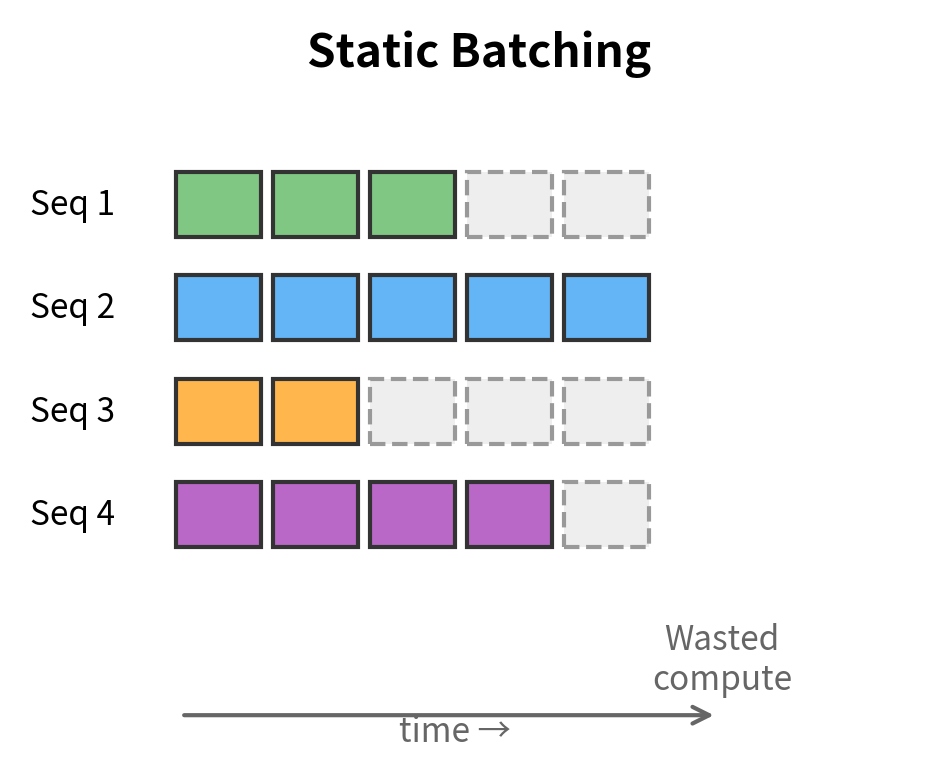

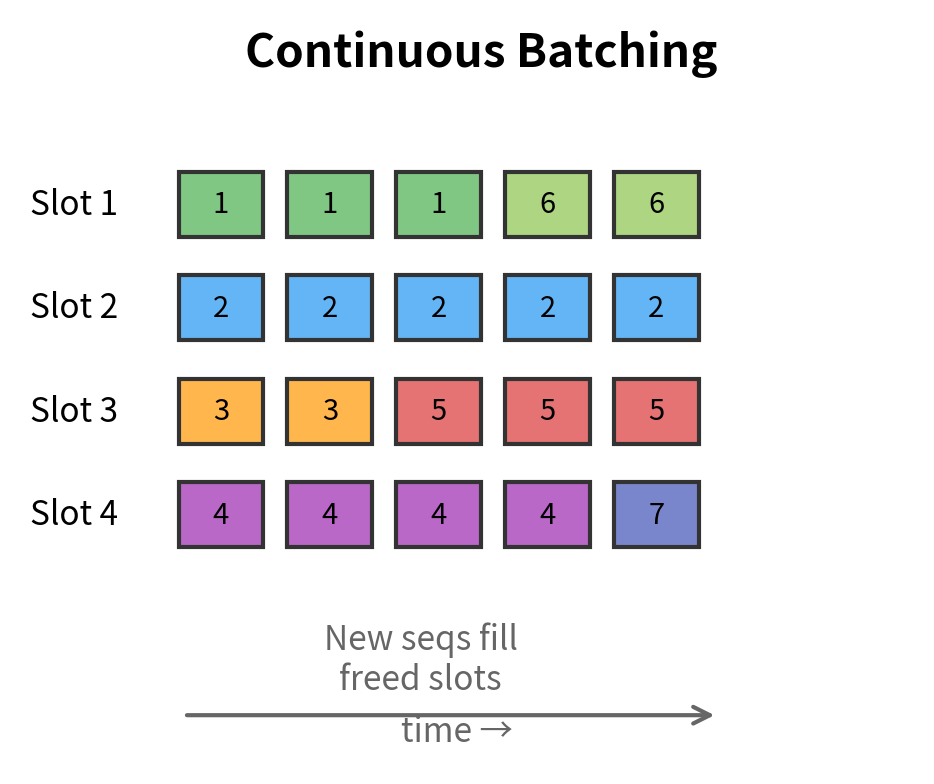

Continuous Batching

For serving multiple users, continuous batching (also called in-flight batching) dynamically adds and removes sequences from a batch as they complete. This maximizes GPU utilization compared to static batching where all sequences must wait for the longest one:

Complete Generation Implementation

Let's put everything together into a complete, production-quality generation function:

The different configurations produce noticeably different outputs. Near-greedy decoding (low temperature) gives focused, predictable completions. Higher temperature introduces more variety but can become less coherent. Top-k and nucleus sampling offer different ways to balance diversity and quality. The right choice depends on your application: creative writing benefits from higher diversity, while factual Q&A typically works better with lower temperature.

Limitations and Considerations

Autoregressive generation, while powerful, comes with inherent limitations that affect both capability and deployment.

The sequential nature of generation creates a fundamental latency floor. No matter how fast each token can be generated, producing 100 tokens requires at least 100 sequential steps. This contrasts with encoding, where an entire sequence can be processed in parallel. For applications requiring very long outputs, this sequential bottleneck becomes significant. Techniques like speculative decoding and parallel draft trees attempt to mitigate this, but the fundamental constraint remains.

KV cache memory grows linearly with sequence length, which can become problematic for very long contexts. A 7B parameter model with 32 layers and a 128K context window might require tens of gigabytes just for the cache. This has motivated research into cache compression techniques like sliding window attention, sparse attention patterns, and cache eviction strategies. Some systems maintain only a fixed-size cache of the most recent tokens, trading off the ability to attend to distant context for bounded memory usage.

The quality of generated text depends heavily on decoding strategy. Greedy decoding, while deterministic, often produces repetitive or generic outputs. Temperature sampling introduces diversity but can also produce incoherent text at high temperatures. Beam search explores multiple hypotheses but tends toward generic, high-probability sequences. Finding the right balance for each application requires experimentation.

Summary

Autoregressive generation is the fundamental process by which decoder-only transformers produce text. The key concepts covered in this chapter include:

-

Generation loop: At each step, the model predicts a probability distribution over the vocabulary, samples or selects the next token, appends it to the sequence, and repeats until a stopping criterion is met.

-

KV caching: By caching the key and value projections from previous positions, we avoid redundant computation during generation. This transforms the computational cost from quadratic to linear in sequence length, making practical generation possible.

-

Stopping criteria: Generation can terminate via EOS tokens for natural endings, maximum length limits for bounded outputs, or custom stop sequences for structured outputs like chat turns.

-

Speed optimizations: Batch processing, mixed precision, speculative decoding, quantization, and continuous batching all contribute to making generation practical for production deployments.

-

Memory trade-offs: KV caching trades memory for computation. For long sequences or large batch sizes, cache memory can become a significant constraint.

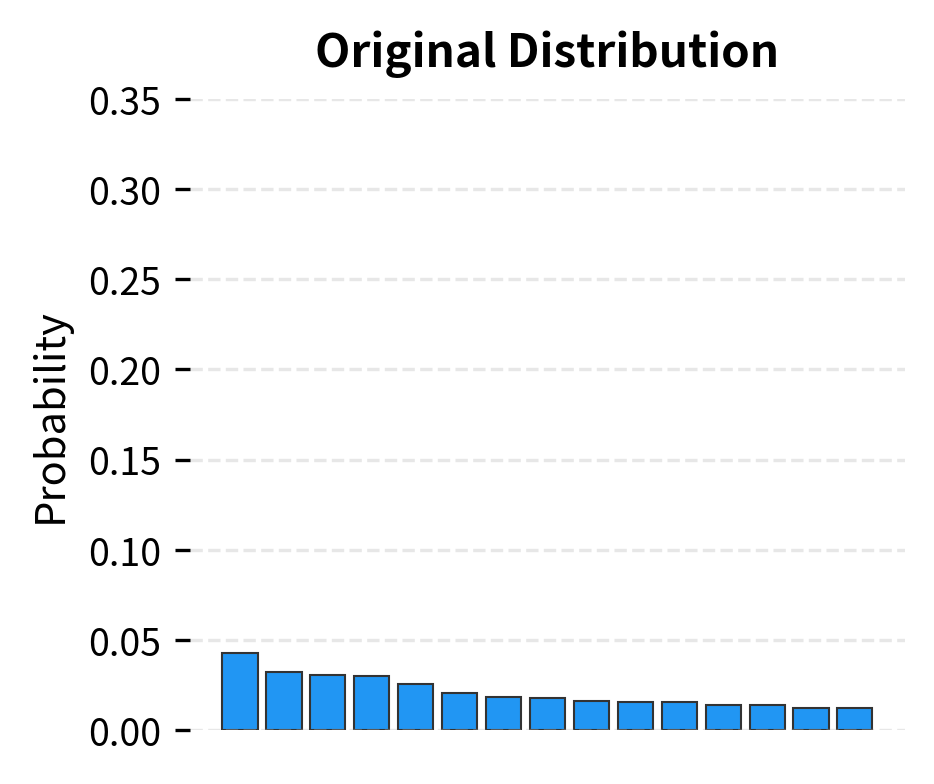

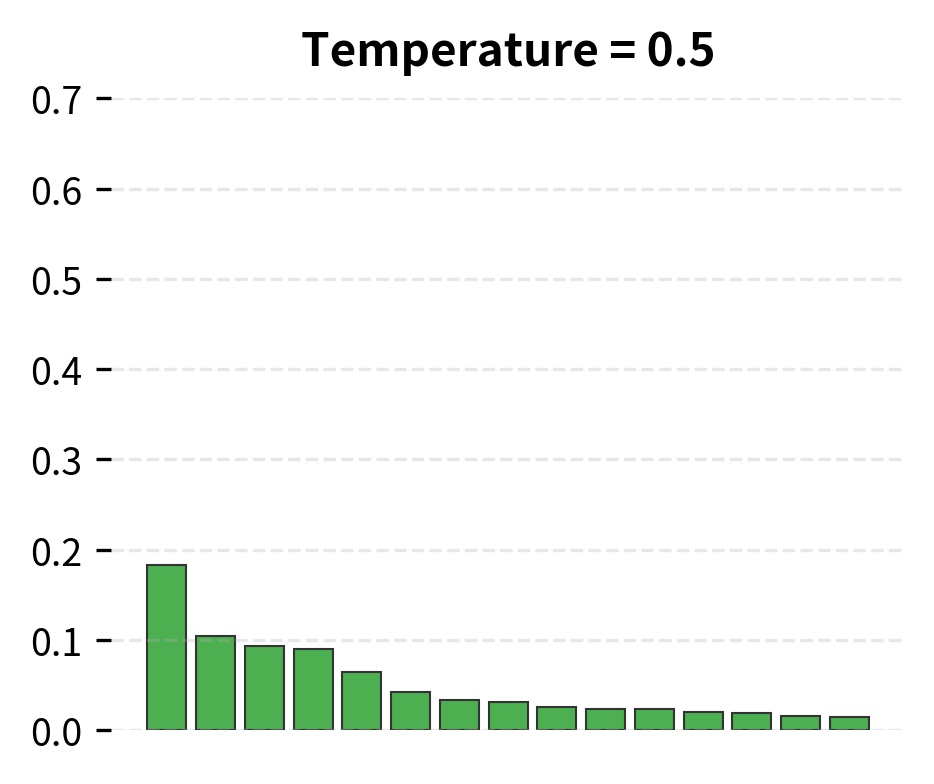

The generation procedure we've explored here forms the foundation for all the decoding strategies covered in subsequent chapters. Temperature scaling, top-k sampling, nucleus sampling, and repetition penalties all operate within this basic framework, modifying how we select the next token from the model's predicted distribution.

Key Parameters

When implementing autoregressive generation, these parameters have the most significant impact on behavior and performance:

-

max_new_tokens: Maximum number of tokens to generate. Set based on your application's typical output length. Shorter limits reduce latency and memory usage. Longer limits allow more complete responses but increase the risk of degenerate outputs.

-

temperature: Controls the randomness of token selection (covered in detail in the next chapter). Values below 1.0 make the distribution sharper, favoring high-probability tokens. Values above 1.0 flatten the distribution, increasing diversity. Use 0.0-0.3 for factual tasks, 0.7-1.0 for creative tasks.

-

use_cache: Whether to use KV caching for efficient generation. Should almost always be

Truefor inference. Only disable for debugging or when memory is extremely constrained. -

pad_token_id: Token ID used for padding in batched generation. Must be set to a valid token ID (often the EOS token ID) to avoid errors with variable-length sequences.

-

do_sample: Whether to sample from the probability distribution (

True) or use greedy decoding (False). Greedy decoding is deterministic but often repetitive. Sampling introduces variety but requires tuning temperature and other sampling parameters. -

stop_sequences: List of strings that trigger generation to stop. Useful for structured outputs, chat applications, and preventing runaway generation. Processed after each token, so slight performance overhead.

-

batch_size: Number of sequences to generate in parallel. Larger batches improve throughput but increase memory usage. Find the sweet spot based on your GPU memory and latency requirements.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about autoregressive generation and KV caching.

Comments