Learn how nucleus sampling dynamically selects tokens based on cumulative probability, solving top-k limitations for coherent and creative text generation.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Nucleus Sampling

When GPT models generate text, they face a fundamental challenge: how do you sample from a probability distribution over thousands of possible next tokens in a way that produces coherent, creative, and diverse text? We've seen how temperature scaling adjusts the sharpness of the distribution and how top-k sampling restricts choices to the k most likely tokens. But top-k has a flaw: the number of reasonable next tokens varies dramatically depending on context. Sometimes only one or two tokens make sense; other times, dozens are equally valid.

Nucleus sampling, introduced by Holtzman et al. in 2020, solves this problem. Instead of fixing the number of candidate tokens, it dynamically selects the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds a threshold . This adaptive approach captures the "nucleus" of the probability mass, keeping high-probability tokens while excluding the unreliable tail, regardless of how many tokens that requires.

The Problem with Fixed-k Sampling

Top-k sampling works by selecting the tokens with the highest probabilities and redistributing probability mass among them. This works well when the model's confidence is consistent, but language is anything but consistent.

Consider two scenarios:

-

High certainty: The model predicts "The capital of France is ___" and assigns 95% probability to "Paris". Here, sampling from the top 50 tokens includes 49 tokens that collectively share only 5% of the probability mass, many of which would produce nonsensical completions.

-

Low certainty: The model predicts "I had a wonderful ___" where "day", "time", "experience", "meal", "trip", and dozens of other tokens are all reasonable. With top-k=10, we might exclude perfectly valid continuations.

The core issue is that is a hyperparameter that cannot adapt to the context. What we really want is to keep all tokens that represent "reasonable" choices, and the most principled way to define "reasonable" is through probability mass.

The Top-p Formulation

The insight behind nucleus sampling is simple: instead of asking "how many tokens should I consider?", we ask "how much probability mass should I capture?" This shift in perspective leads to an adaptive algorithm that naturally handles both high-confidence and uncertain predictions.

From Intuition to Definition

Think about what we really want when sampling the next token. We want to include all tokens that have a reasonable chance of being correct, and exclude all tokens that are essentially noise. But "reasonable" depends on context. After "The sky is", the token "blue" might have 40% probability, meaning we should consider other options. After "2 + 2 =", the token "4" might have 99% probability, meaning alternatives are probably mistakes.

The key insight is that probability itself tells us what's reasonable. If we capture 90% of the total probability mass, we've included essentially all the tokens the model considers plausible. Everything in the remaining 10% is, by definition, something the model thinks is unlikely.

This leads us to define the nucleus as the smallest set of highest-probability tokens that together account for at least fraction of the total probability. Formally, given a probability distribution over vocabulary , the nucleus is the minimal set such that:

where:

- : the nucleus, the minimal set of highest-probability tokens we'll sample from

- : the probability assigned to token by the model

- : the cumulative probability threshold, typically set between 0.9 and 0.95

The nucleus is the minimal set of highest-probability tokens whose cumulative probability mass meets or exceeds the threshold . Tokens outside the nucleus are discarded, and the remaining probabilities are renormalized.

The Algorithm Step by Step

How do we actually find this minimal set? The algorithm is straightforward once you see the logic:

-

Sort tokens by probability in descending order. This puts the most likely tokens first.

-

Walk through the sorted list, accumulating probabilities. Keep adding tokens until your running sum reaches or exceeds .

-

Stop as soon as you cross the threshold. The tokens you've accumulated form the nucleus. Discard everything else.

-

Renormalize so that the remaining probabilities sum to 1, giving you a valid distribution to sample from.

Let's express this mathematically. After sorting, we have tokens ordered so that , where is the vocabulary size. We find the smallest such that:

where:

- : the token with the -th highest probability

- : the number of tokens in the nucleus (determined dynamically based on the distribution)

- : the total vocabulary size

The nucleus is then , containing exactly the top tokens needed to reach the probability threshold. The key property of this formulation is that emerges from the distribution itself. A peaked distribution yields small ; a flat distribution yields large .

Why Renormalization Matters

After truncating to the nucleus, the probabilities no longer sum to 1. If our nucleus contains 90% of the probability mass, the probabilities inside it sum to 0.90, not 1.0. To sample correctly, we need to renormalize.

The renormalized probability for each token in the nucleus is simply its original probability divided by the total probability mass in the nucleus:

where:

- : the renormalized probability used for sampling

- : the original probability of token

- : the sum of original probabilities over all tokens in the nucleus, which serves as the normalizing constant

This renormalization preserves the relative ordering of tokens. If "nice" was twice as likely as "good" before, it remains twice as likely after. We're simply scaling everything up so the probabilities form a valid distribution that sums to 1.

A Worked Example

Abstract formulas come alive with concrete numbers. Let's trace through nucleus sampling step by step with a realistic example.

Setting Up the Problem

Suppose a language model predicts the next token after "The weather is" and produces the following probability distribution:

| Token | Probability |

|---|---|

| nice | 0.35 |

| good | 0.25 |

| bad | 0.15 |

| great | 0.10 |

| terrible | 0.05 |

| wonderful | 0.04 |

| cold | 0.03 |

| hot | 0.02 |

| (other tokens) | 0.01 |

This distribution is already sorted by probability. The model strongly favors positive weather descriptions, with "nice" and "good" together accounting for 60% of the mass.

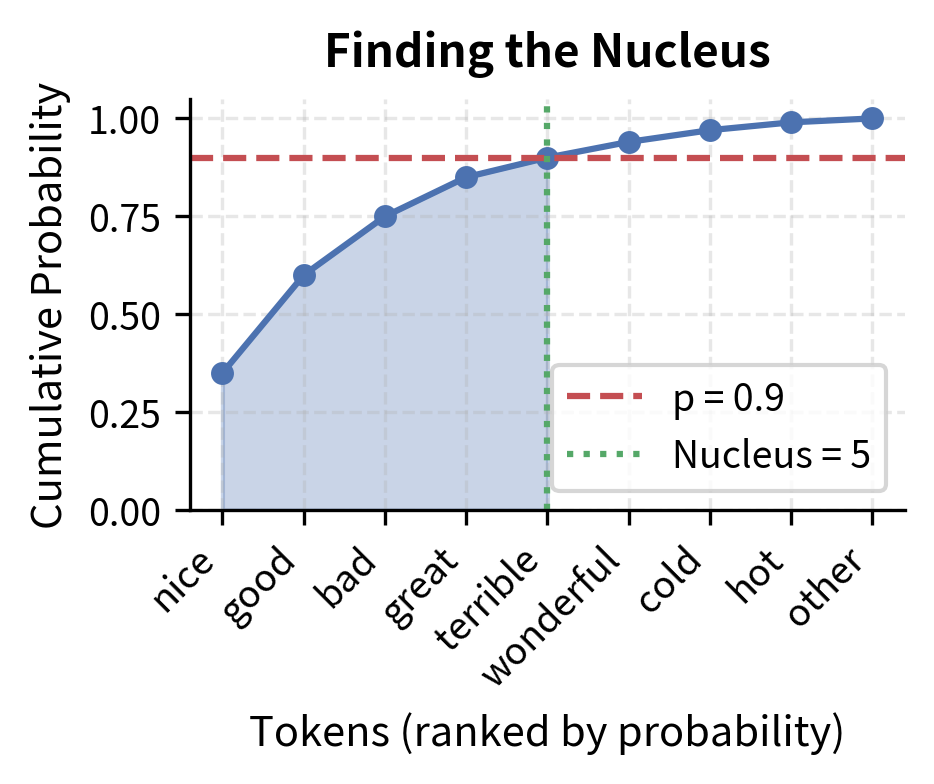

Finding the Nucleus

With , we walk through the tokens from highest to lowest probability, keeping a running sum:

| Step | Token | Probability | Cumulative Sum | In Nucleus? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nice | 0.35 | 0.35 | ✓ |

| 2 | good | 0.25 | 0.60 | ✓ |

| 3 | bad | 0.15 | 0.75 | ✓ |

| 4 | great | 0.10 | 0.85 | ✓ |

| 5 | terrible | 0.05 | 0.90 | ✓ (threshold reached) |

| 6 | wonderful | 0.04 | — | ✗ (excluded) |

| 7 | cold | 0.03 | — | ✗ (excluded) |

At step 5, our cumulative sum hits exactly 0.90, meeting the threshold. We stop here. The nucleus is {"nice", "good", "bad", "great", "terrible"}, containing 5 tokens.

Notice what happened: we didn't need to decide in advance how many tokens to include. The distribution itself determined that 5 tokens were needed to capture 90% of the probability mass.

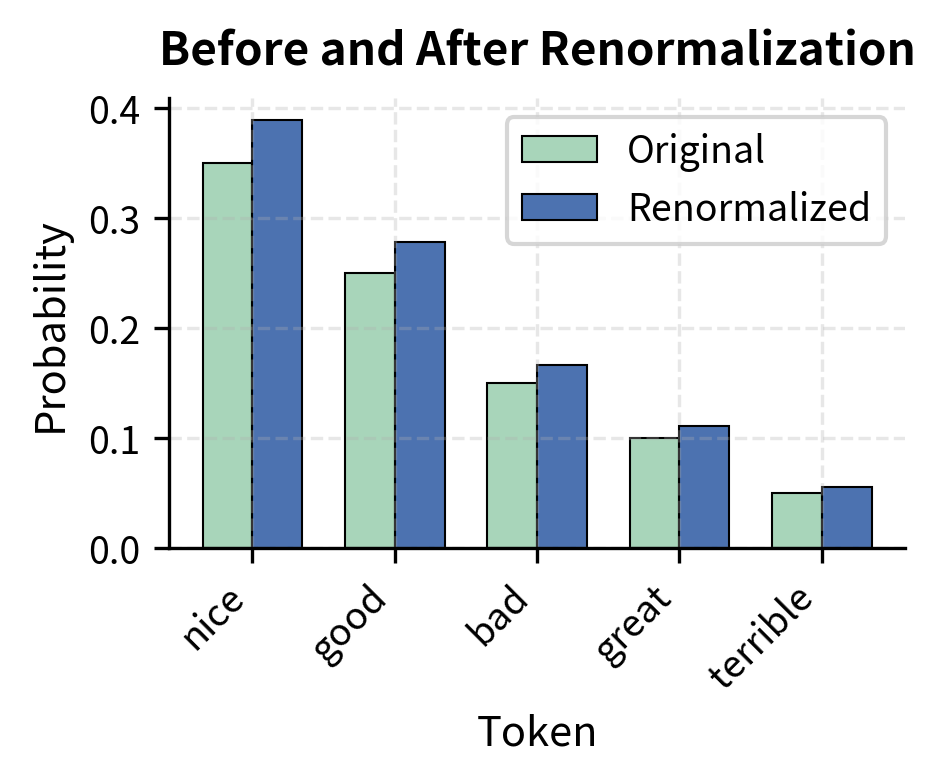

Renormalizing for Sampling

The five tokens in our nucleus have probabilities summing to 0.90. To sample from a valid probability distribution, we divide each by this sum:

| Token | Original | Calculation | Renormalized |

|---|---|---|---|

| nice | 0.35 | 0.389 | |

| good | 0.25 | 0.278 | |

| bad | 0.15 | 0.167 | |

| great | 0.10 | 0.111 | |

| terrible | 0.05 | 0.056 |

You can verify: (the small discrepancy is rounding). We now have a valid probability distribution over just five tokens.

The left panel shows how cumulative probability grows as we add tokens. The curve rises steeply at first (the top tokens contribute most of the mass) then flattens. We stop when we cross . The right panel shows how renormalization scales up each probability proportionally, preserving relative rankings while creating a valid distribution.

Comparing to Top-k

In this particular case, top-k=5 would include the same tokens. But consider what happens if the model were 90% confident in a single token. Say "Paris" has 0.90 probability and everything else shares the remaining 0.10.

With nucleus sampling at , we'd include just "Paris" (0.90 meets the threshold immediately). With top-k=5, we'd include "Paris" plus four tokens that collectively have only 10% probability. Those four tokens are noise that nucleus sampling correctly excludes.

This is the adaptive behavior that makes nucleus sampling effective: it contracts when the model is confident and expands when the model is uncertain.

Implementation

Now that we understand the algorithm conceptually, let's implement it. We'll build nucleus sampling from scratch, verify it works correctly, then see how to use the production-ready version in Hugging Face's transformers library.

Building the Core Algorithm

The implementation follows our algorithm directly. We'll work with logits (the raw model outputs before softmax), apply optional temperature scaling, convert to probabilities, then perform the nucleus truncation.

One subtlety deserves attention: the shift operation in the cutoff logic. When we compute cumulative_probs > p, the first position where this is True is the token that crosses the threshold. But we want to include that token in the nucleus, not exclude it. The shift ensures we remove tokens after the one that crosses the threshold, keeping the nucleus at exactly the right size.

Verifying Our Implementation

Let's confirm our implementation produces the expected behavior using the "weather" example:

The samples concentrate on the five nucleus tokens, with "wonderful" appearing rarely or never. The empirical frequencies should approximate our renormalized probabilities: "nice" around 39%, "good" around 28%, and so on.

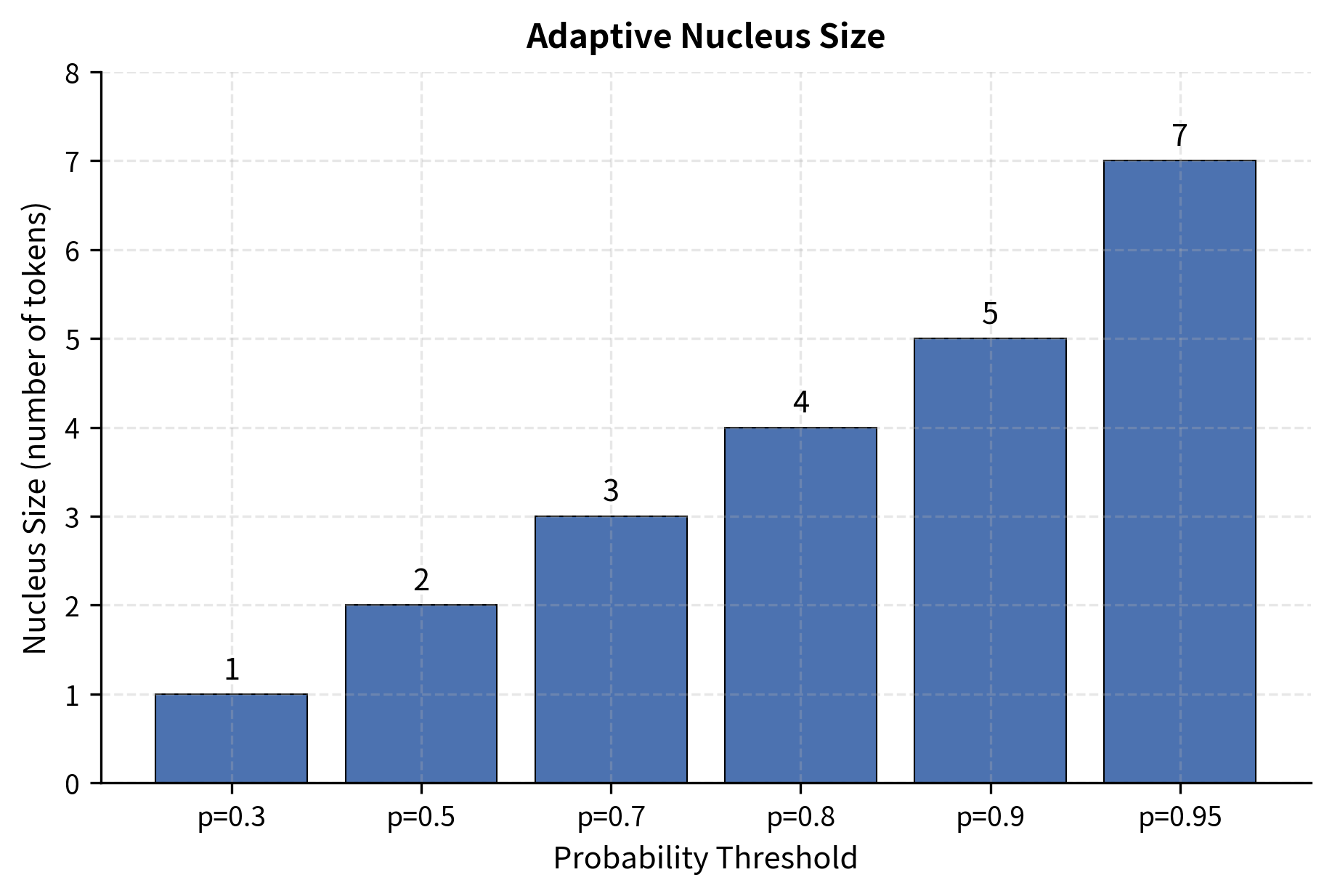

Visualizing Adaptive Nucleus Size

The real insight comes from seeing how nucleus size varies with . Let's visualize this:

With our example distribution, requires only 1 token (just "nice" at 35%), while needs 6 tokens. The relationship is non-linear because probability mass concentrates in the top tokens. Moving from to adds just one token, but moving from to also adds one. Each additional token contributes less marginal probability.

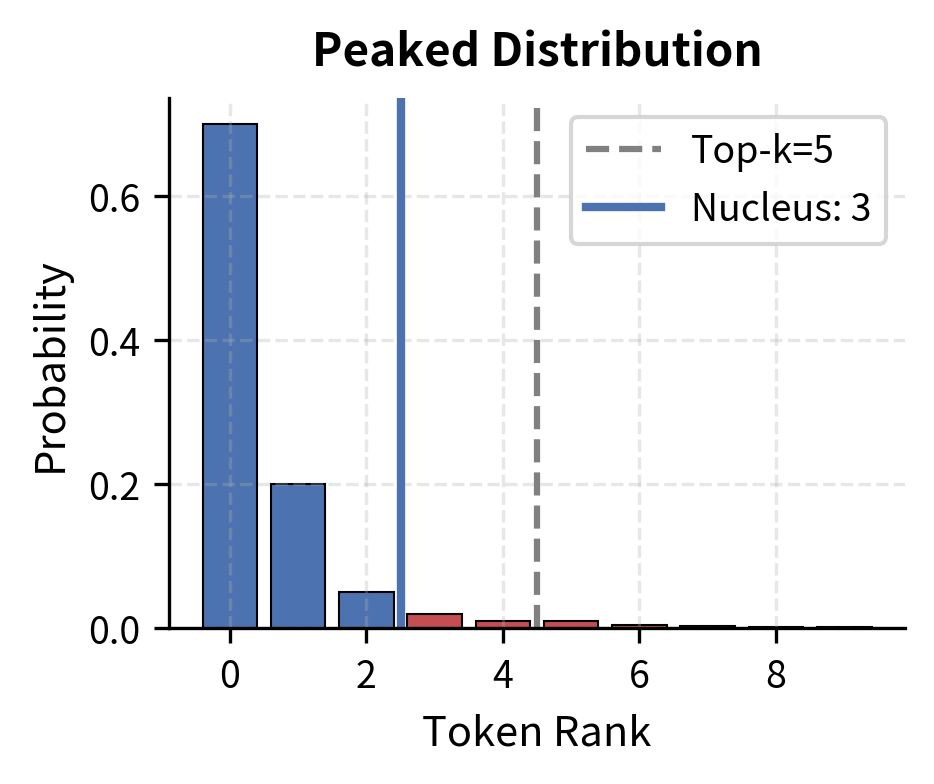

The Adaptive Advantage: Peaked vs. Flat Distributions

The advantage of nucleus sampling becomes clear when we compare it to top-k across different distributional shapes. Consider two scenarios:

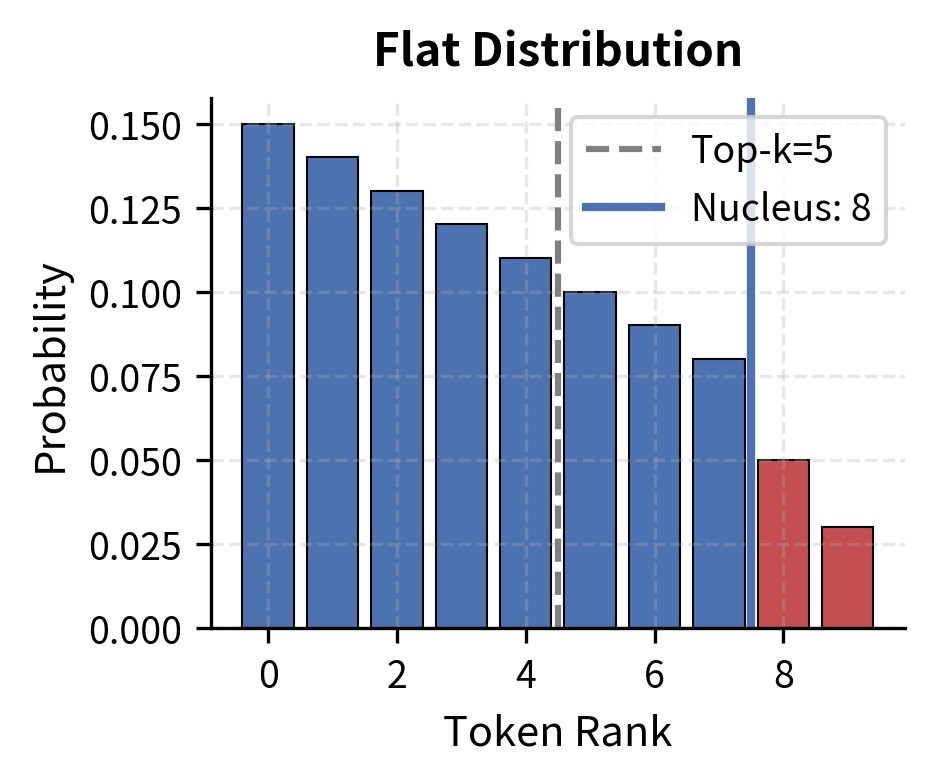

These visualizations show why nucleus sampling outperforms top-k. When the model is confident (peaked distribution), nucleus sampling automatically tightens to just 2 tokens, while top-k=5 wastefully includes 3 near-zero tokens. When the model is uncertain (flat distribution), nucleus sampling expands to 8 tokens to capture the spread probability mass, while top-k=5 arbitrarily excludes 3 reasonable options.

Top-k makes the same decision regardless of context. Nucleus sampling reads the distribution and responds appropriately.

Production Use with Hugging Face Transformers

In practice, you won't implement nucleus sampling yourself. The transformers library provides it out of the box. Here's how to generate text with GPT-2 using top-p:

The generate() method accepts top_p directly. Set do_sample=True to enable sampling, and top_k=0 to disable top-k filtering so nucleus sampling operates alone:

Each completion takes a different path while remaining coherent. At every generation step, nucleus sampling includes only tokens the model considers plausible, allowing for creativity without introducing obvious errors.

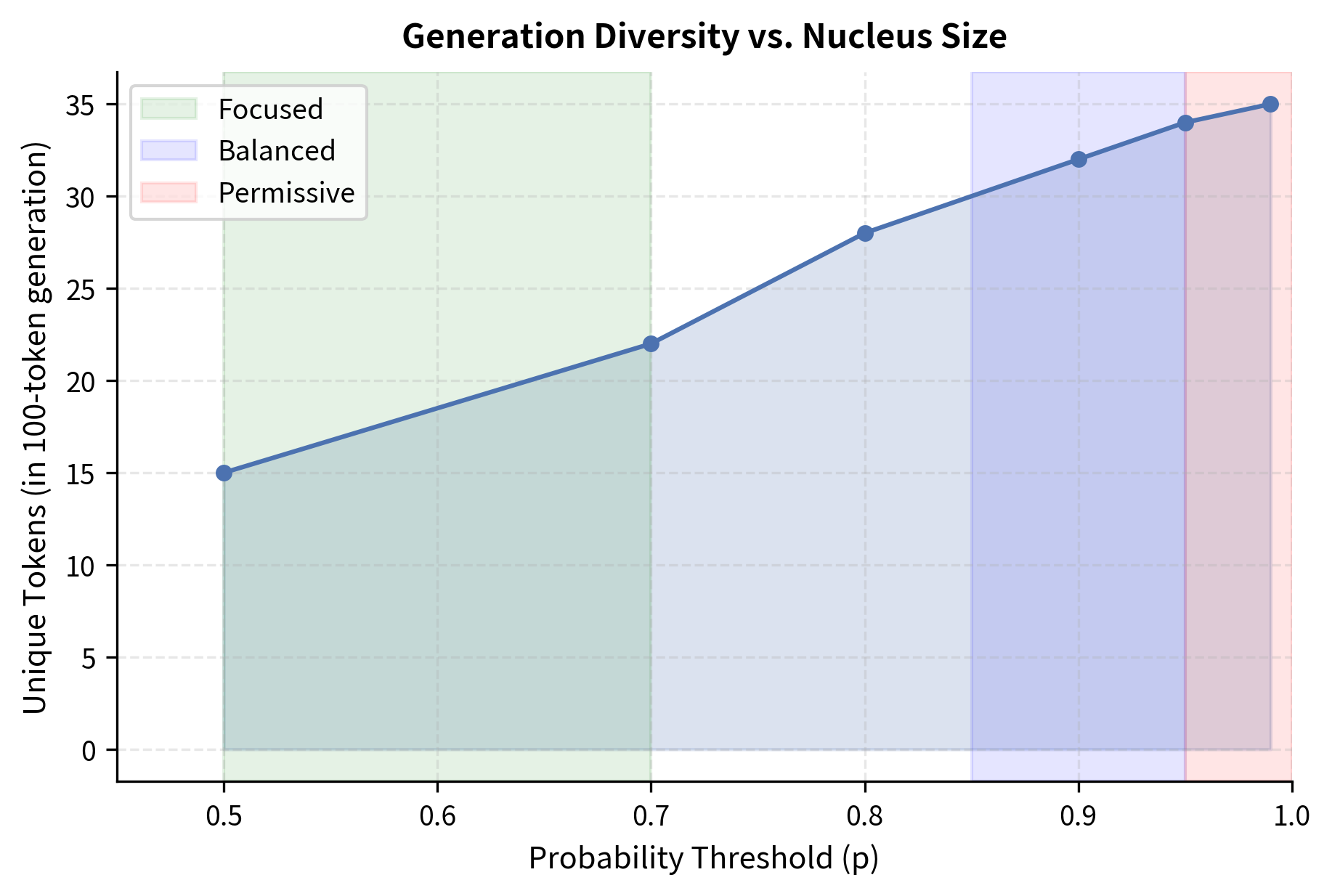

Choosing the Right p Value

The probability threshold controls the trade-off between creativity and coherence. Here are practical guidelines for selecting :

-

to : General-purpose creative writing. This is the most common setting and works well for story generation, dialogue, and open-ended tasks. The nucleus is large enough for variety but excludes the unreliable tail.

-

to : More focused generation. Useful when you want coherent output with moderate diversity, such as paraphrasing or generating multiple options for the same intent.

-

: Very focused generation. Approaches greedy decoding behavior. Use for tasks requiring high precision, like code completion or factual responses.

-

: Very permissive. Rarely used alone because it includes many low-probability tokens. Can produce surprising but occasionally incoherent outputs.

Let's visualize how affects generation diversity:

Combining Nucleus Sampling with Temperature

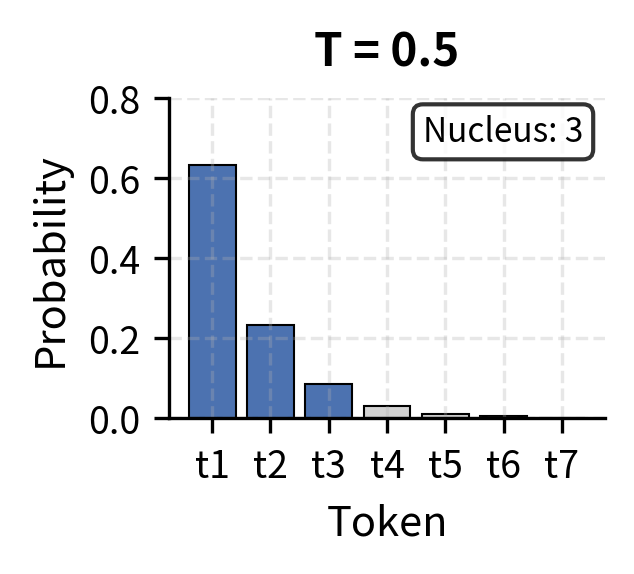

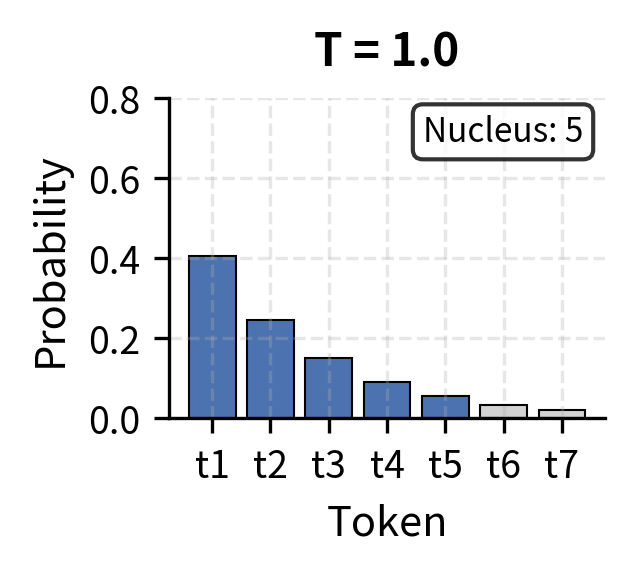

Nucleus sampling and temperature scaling address different aspects of the probability distribution. Temperature reshapes the distribution, making it more peaked or more uniform. Nucleus sampling then truncates based on the reshaped distribution.

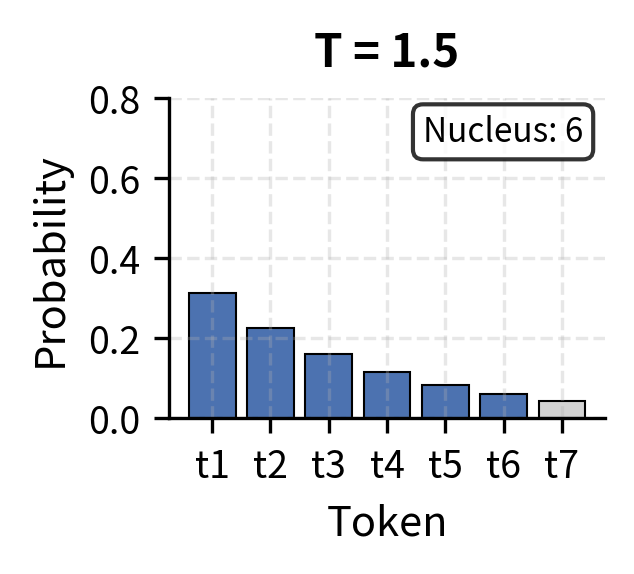

The visualization above shows how temperature and nucleus size interact. At low temperature (T=0.5), probability concentrates heavily in the top token, so the nucleus contains just 1-2 tokens. At high temperature (T=1.5), probability spreads more evenly, requiring 5+ tokens to capture 90% of the mass. This interaction lets you fine-tune generation behavior: temperature controls the shape of the distribution, while the nucleus threshold determines how much of that reshaped distribution you sample from.

Using both together gives you fine-grained control:

- Low temperature + high p: Coherent output with some variety. The temperature concentrates probability mass, while high p still allows sampling from multiple tokens.

- High temperature + low p: Unusual but still controlled. Temperature spreads probability, but low p keeps only the tokens that remain relatively high after spreading.

- High temperature + high p: Maximum creativity. Use with caution as outputs can become incoherent.

The focused outputs with lower temperature tend to stay closer to common phrasings and high-probability continuations. The creative outputs with higher temperature explore more unusual word choices and directions, though they may occasionally produce less coherent passages. Finding the right balance depends on your application: conversational AI typically benefits from moderate settings, while creative writing tools can push toward higher values.

Nucleus Sampling vs. Top-k: When to Use Which

Both methods truncate the vocabulary, but they do so with different philosophies:

| Aspect | Top-k | Nucleus (Top-p) |

|---|---|---|

| Truncation criterion | Fixed count | Probability mass |

| Adapts to context | No | Yes |

| Parameter intuition | "Keep this many options" | "Keep this much probability" |

| Risk of over-truncation | Yes (when few tokens dominate) | No |

| Risk of under-truncation | Yes (when probability spreads) | No |

| Compute cost | Slightly lower (no cumsum) | Slightly higher |

In practice, nucleus sampling is preferred for creative text generation because of its adaptive behavior. Top-k remains useful when you want explicit control over the number of options or when slight computational savings matter at scale.

Some systems use both: first apply top-k as a coarse filter (e.g., k=100), then apply nucleus sampling within that set. This combines the efficiency of top-k with the adaptivity of top-p.

Limitations and Impact

Nucleus sampling represented a significant advance in text generation quality, but it comes with limitations worth understanding.

The choice of remains a hyperparameter that requires tuning. While works well in many settings, different tasks and domains may benefit from different thresholds. There's no universal value that works optimally across all contexts, and the "right" can even vary within a single generation as the model moves through different parts of a sequence. For instance, the beginning of a story might benefit from higher to establish creative premises, while later passages benefit from lower to maintain consistency.

Nucleus sampling also doesn't address all failure modes of autoregressive generation. Repetition loops, factual errors, and incoherent long-range structure can still occur. The method operates on local token probabilities and has no mechanism for enforcing global coherence or factual accuracy. Modern systems often combine nucleus sampling with additional techniques like repetition penalties, contrastive search, or post-hoc filtering.

The cumulative probability computation adds modest overhead compared to simpler methods like pure sampling or greedy decoding. For most applications this is negligible, but in latency-critical systems processing millions of requests, it can add up. Optimized implementations pre-sort once and reuse the sorted indices.

Despite these limitations, nucleus sampling's impact on practical text generation has been substantial. It became the default sampling method in many popular language model interfaces and APIs. The insight that truncation should adapt to distributional shape rather than use a fixed count influenced subsequent work on decoding strategies. Nucleus sampling also gave practitioners a principled way to balance coherence and creativity that was previously achieved only through extensive trial-and-error with temperature and top-k.

Key Parameters

When using nucleus sampling in Hugging Face's generate() method, the following parameters control the sampling behavior:

-

top_p(float, 0.0 to 1.0): The cumulative probability threshold. Only tokens whose cumulative probability mass is within this threshold are considered. Higher values include more tokens, increasing diversity. Typical range: 0.9 to 0.95 for creative tasks, 0.7 to 0.9 for more focused generation. -

temperature(float, > 0): Scales the logits before applying softmax. Values below 1.0 sharpen the distribution (more deterministic), values above 1.0 flatten it (more random). Applied before nucleus truncation. -

top_k(int): When using nucleus sampling alone, set to 0 to disable top-k filtering. Can be combined with top-p for hybrid filtering. -

do_sample(bool): Must be set toTrueto enable any sampling strategy. WhenFalse, the model uses greedy decoding. -

num_return_sequences(int): Number of independent completions to generate. Useful for generating multiple diverse options.

Summary

Nucleus sampling addresses a fundamental limitation of top-k sampling by adapting the number of candidate tokens to the probability distribution at each step. Rather than asking "how many tokens should I consider?", nucleus sampling asks "how much probability mass should I keep?", and this reframing produces more consistent generation quality across varying contexts.

The key ideas are:

- Cumulative probability threshold: The nucleus is the smallest token set whose probabilities sum to at least

- Adaptive truncation: High-confidence predictions yield small nuclei; uncertain predictions yield large nuclei

- Typical values: to for general creative generation

- Combines with temperature: Temperature reshapes the distribution; nucleus sampling truncates it

- Practical default: Nucleus sampling is the most common choice for open-ended generation in modern systems

When implementing text generation, nucleus sampling should be your default starting point. Adjust based on your tolerance for creativity versus coherence, and combine with temperature scaling for finer control over the output distribution.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about nucleus sampling and top-p text generation.

Comments