Learn how to assemble transformer blocks by combining residual connections, normalization, attention, and feed-forward networks. Includes implementation of pre-norm and post-norm variants with worked examples.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Transformer Block Assembly

We've explored each component of a transformer block in isolation: residual connections that enable gradient flow, layer normalization that stabilizes activations, the choice between pre-norm and post-norm configurations, feed-forward networks that inject nonlinearity, and the activation functions and gating mechanisms that power them. Now it's time to assemble these pieces into a complete, working transformer block.

This chapter takes a systems perspective. We'll examine how components connect, understand the data flow through a complete block, implement both encoder and decoder variants, and trace a concrete example through every operation. By the end, you'll have the knowledge to implement transformer blocks from scratch and understand the design decisions that distinguish different architectures.

The Standard Transformer Block

A transformer block is a modular unit that can be stacked to build arbitrarily deep models. Each block takes a sequence of token representations as input and produces a refined sequence as output. The refinement happens through two complementary operations: attention (which mixes information across positions) and the feed-forward network (which transforms each position independently).

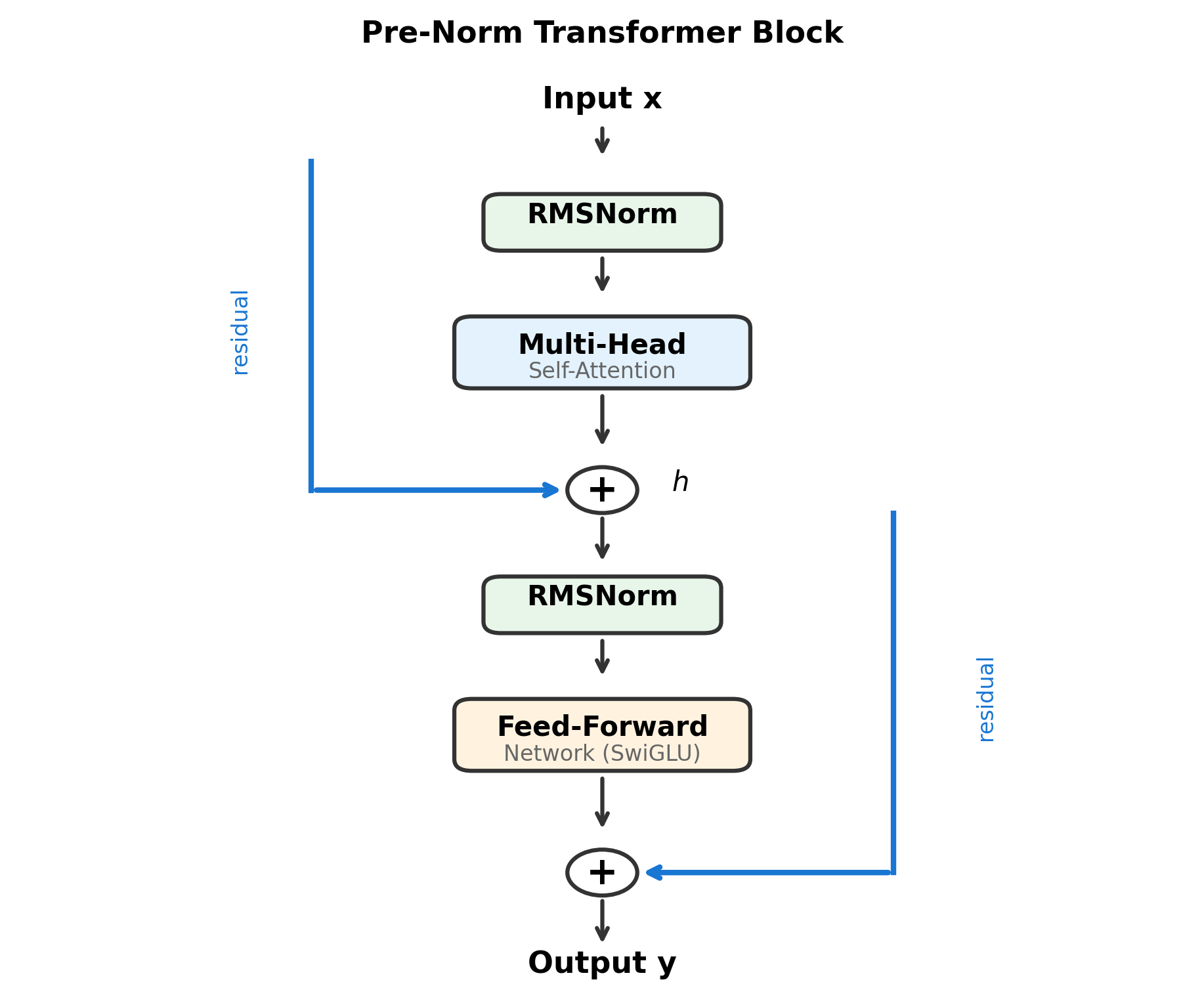

The modern pre-norm block, used in GPT, LLaMA, and most contemporary language models, follows a specific structure. The computation proceeds in two stages (first attention, then feed-forward), with each stage wrapped in a residual connection:

where:

- : the input to the block, a matrix containing tokens (one per row) with -dimensional representations

- : normalization function, typically RMSNorm in modern architectures, which stabilizes activations before each sublayer

- : multi-head self-attention, which allows each token to gather information from other positions in the sequence

- : the feed-forward network, which transforms each token independently through nonlinear layers (potentially with gating like SwiGLU)

- : intermediate representation after the attention sublayer, combining the original input with attention's contribution

- : the block output, passed to the next block in the stack

The structure of each sublayer follows the same pattern: (1) normalize the input, (2) apply the transformation (attention or FFN), and (3) add the result back to the original input via a residual connection. This "normalize → transform → add" pattern repeats for both sublayers.

The normalization appearing before each sublayer (pre-norm) is crucial: it ensures gradients can flow directly through the residual path without being distorted by normalization. This ordering, which we analyzed in the pre-norm vs post-norm chapter, has become the standard for training deep transformer models (50+ layers).

Every transformer block contains exactly two sublayers: attention and feed-forward. Each sublayer follows the same pattern: normalize, transform, add residual. This uniformity simplifies implementation and enables modular stacking of blocks.

Component Inventory

Before diving into implementation, let's catalog the components we'll need. Each has been covered in previous chapters, but seeing them together clarifies their roles.

Normalization layers ensure stable activations by normalizing each token's representation to have consistent statistics. We need one normalization layer before each sublayer, plus optionally a final normalization after all blocks.

Multi-head self-attention enables tokens to gather information from other positions in the sequence. It projects inputs to queries, keys, and values, computes attention weights, and produces context-aware representations.

Feed-forward network transforms each position independently through a two-layer MLP with nonlinearity. Modern architectures often use gated variants like SwiGLU for improved expressiveness.

Residual connections add each sublayer's input directly to its output, creating gradient highways that enable training of deep networks.

Let's implement each component, then assemble them into a complete block:

RMSNorm Implementation

Modern transformers predominantly use RMSNorm over standard LayerNorm due to its computational efficiency. While LayerNorm computes both mean and variance, RMSNorm normalizes by the root mean square alone:

where:

- : the input vector (one token's representation)

- : the root mean square, with for numerical stability

- : learnable scale parameters (initialized to ones)

- : element-wise multiplication

RMSNorm saves compute by skipping the mean calculation and subtraction that LayerNorm requires. Here's the implementation:

Multi-Head Self-Attention

Attention is the mechanism that enables tokens to exchange information. The core computation projects each token into queries (), keys (), and values (), computes attention scores between all query-key pairs, and uses these scores to create weighted combinations of values. Multi-head attention runs this process in parallel across multiple "heads," each learning different attention patterns:

where:

- : input sequence with tokens

- : number of attention heads

- : attention computed for head

- : output projection that combines all heads

We'll implement a clean version that handles the full attention computation:

Feed-Forward Network with SwiGLU

Modern architectures use gated linear units for improved expressiveness. SwiGLU, used in LLaMA and PaLM, combines a gating mechanism with the SiLU activation. The computation applies two parallel projections, one passed through SiLU (the "gate") and one linear (the "up" projection), then multiplies them element-wise:

where:

- : input token representation

- : projection matrices to the hidden dimension

- : projection back to model dimension

- : the Swish activation, where is the sigmoid function

- : element-wise multiplication (the "gating" operation)

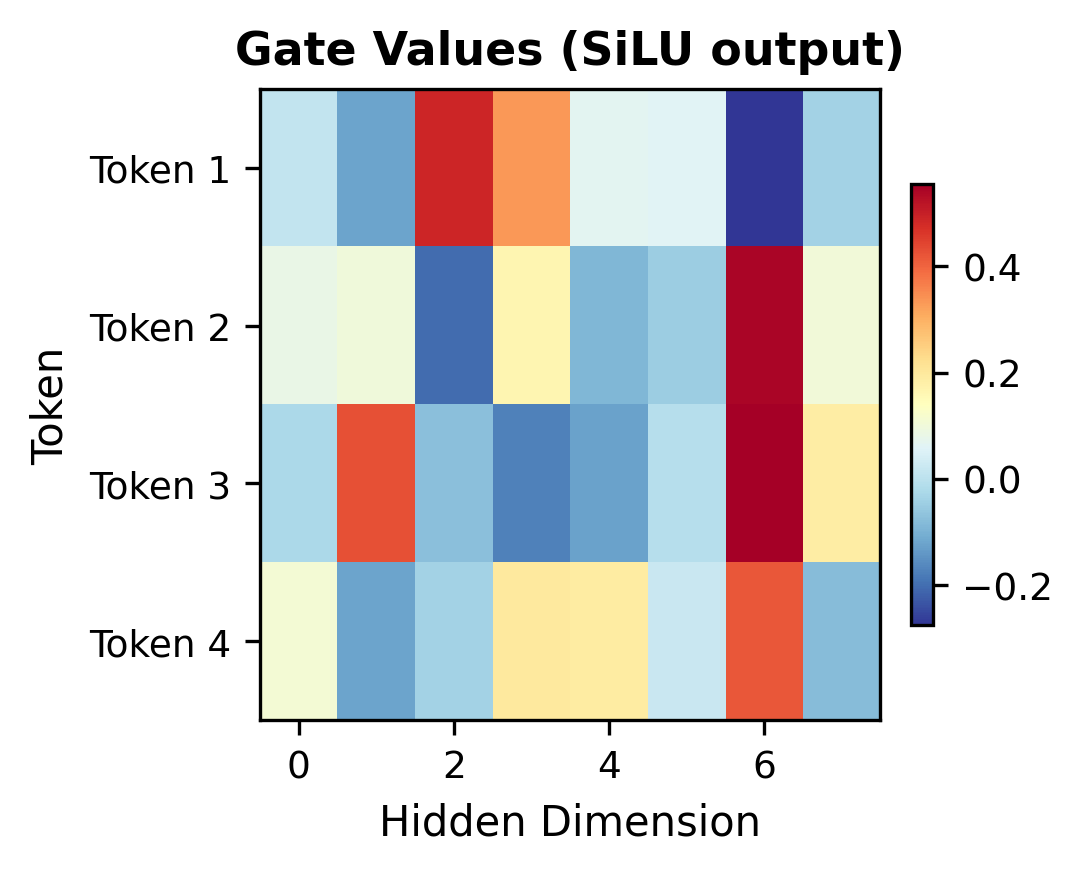

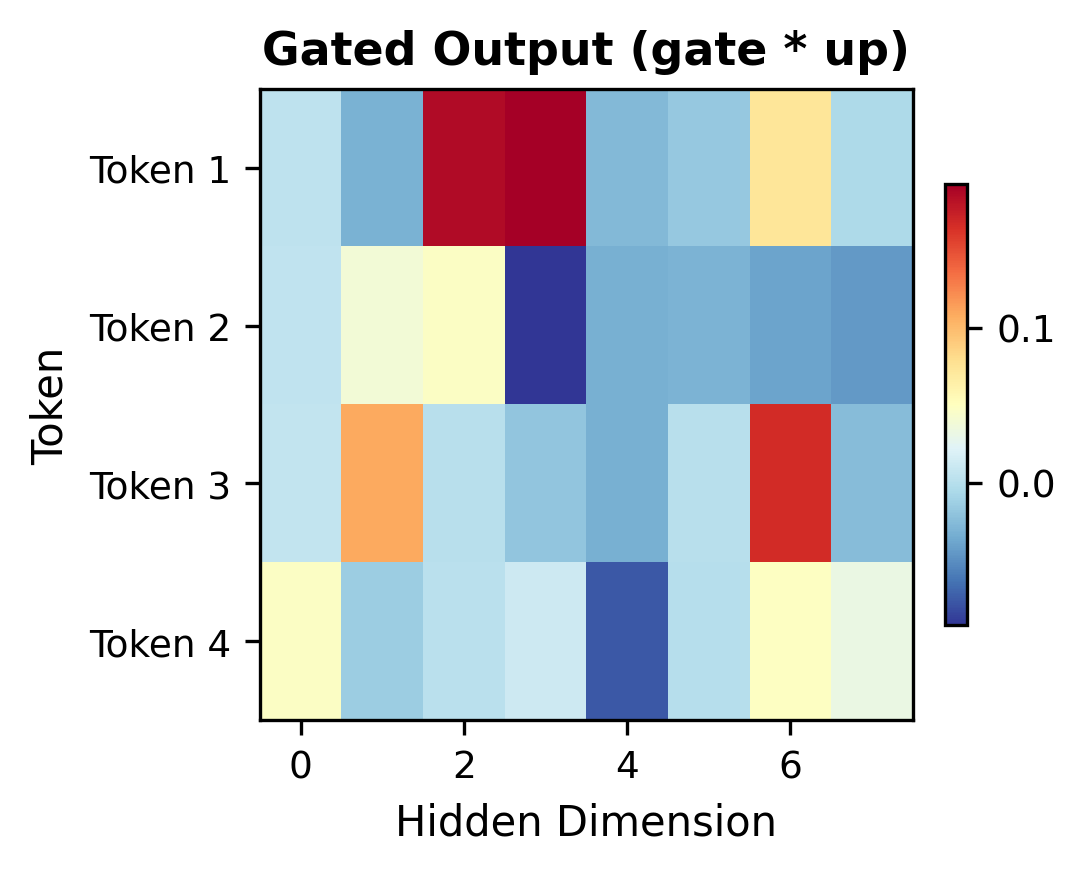

The gating allows the network to selectively pass or block information, providing more expressive power than a simple nonlinearity. To see gating in action, let's visualize how the gate signal modulates the information flow:

The heatmaps illustrate the gating mechanism's selective nature. Notice how dimensions with near-zero gate values (blue) suppress the corresponding up-projection values, while high gate values (red) allow information to pass through. This selective filtering gives SwiGLU its expressive advantage over simple activations.

Here's the implementation:

Assembling the Transformer Block

Now we combine these components into a complete transformer block. The key is getting the ordering right: normalize before each sublayer, apply the transformation, then add the residual.

Let's test the block and examine its behavior:

The block preserves the shape of its input: 16 tokens with 512 dimensions go in, and 16 tokens with 512 dimensions come out. The output statistics differ from the input, reflecting the transformations applied by attention and the FFN.

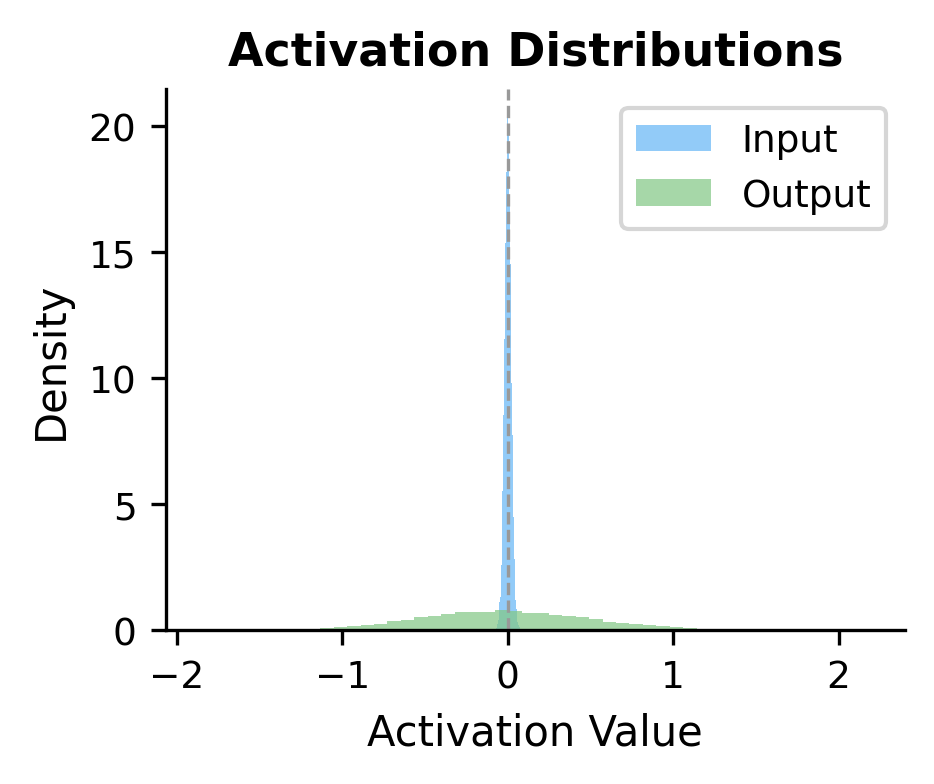

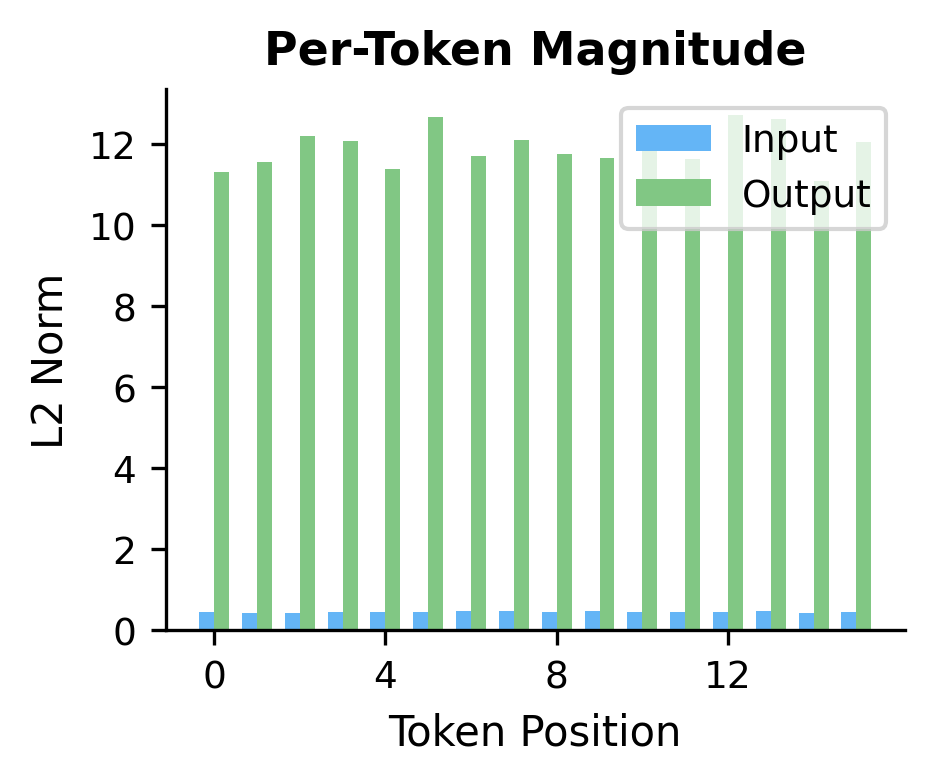

To understand how the block transforms representations, let's compare the input and output for each token:

The histograms show that the block broadens the distribution of activation values, while the per-token norms reveal that different tokens are transformed by varying amounts. This position-dependent transformation is a signature of the attention mechanism, which allows tokens to selectively incorporate information from other positions.

Visualizing the Block Structure

The component relationships become clearer with a visual diagram:

The diagram makes the pre-norm pattern explicit. At each sublayer, the input first passes through RMSNorm, then through the main transformation (attention or FFN), and finally the result is added back to the original input via the residual connection. The blue residual paths bypass the transformations entirely, ensuring gradients can flow directly from output to input.

A Worked Example: Token by Token

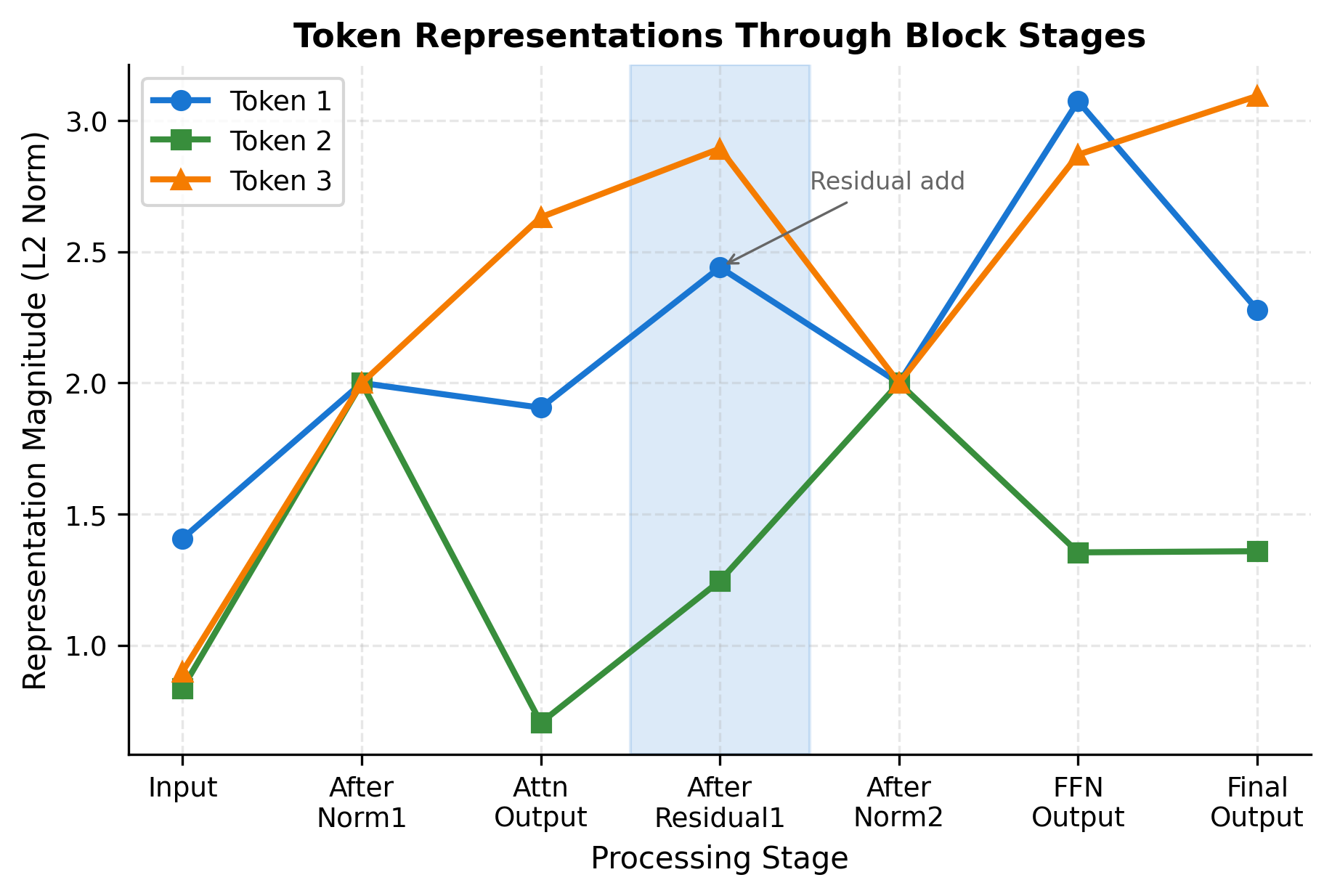

To truly understand how data flows through a transformer block, let's trace a small concrete example with actual numbers. We'll use a tiny configuration so you can follow each computation:

- : each token is represented by just 4 numbers

- : we split attention into 2 parallel heads

- : the FFN's hidden layer has 8 dimensions

- : our sequence contains 3 tokens

Let's visualize how each token's representation evolves through the block stages:

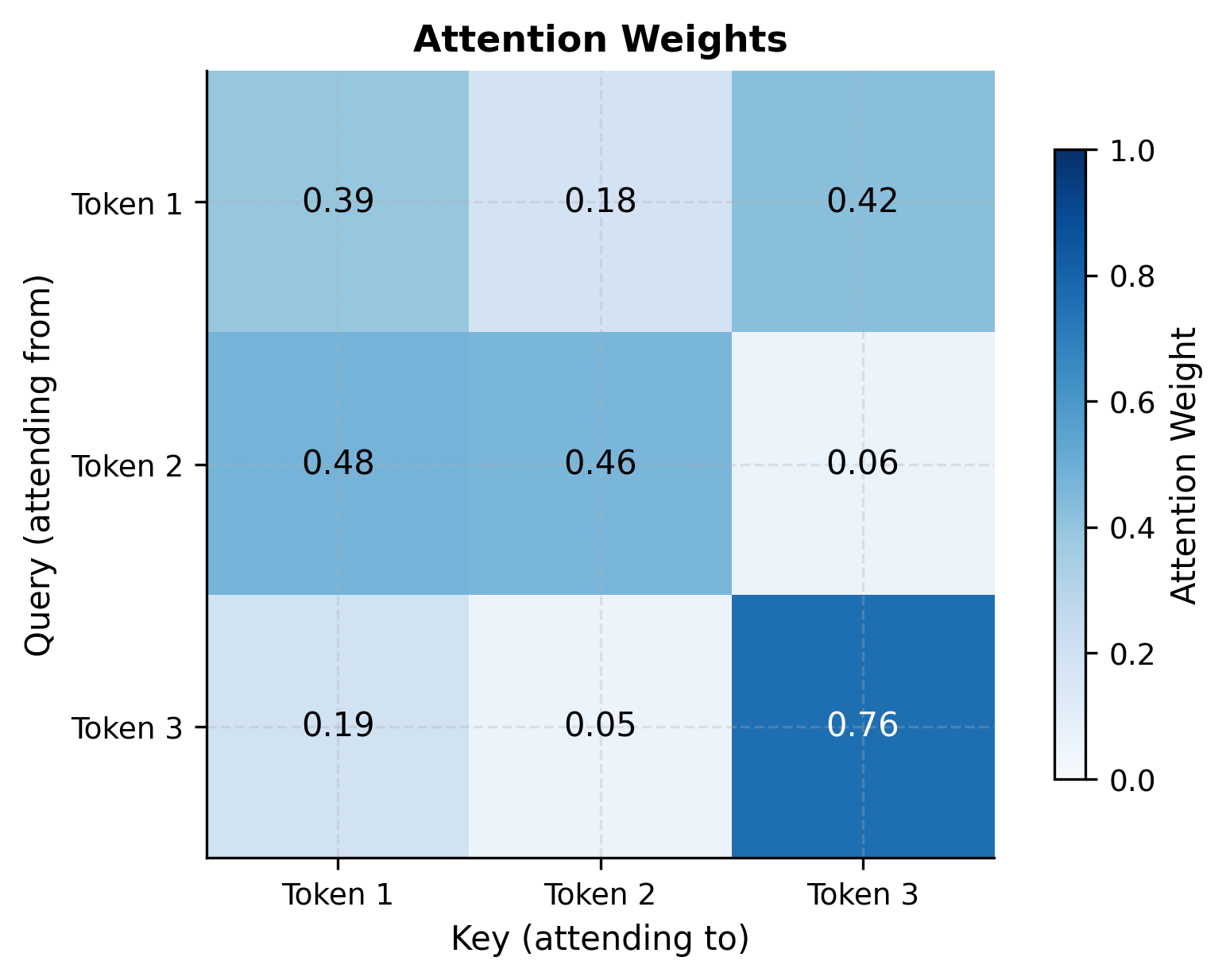

Understanding the Attention Weights

The attention weights matrix shows how each token attends to others in the sequence. Let's visualize this pattern:

Each row in the attention matrix sums to 1.0 (due to softmax normalization). If we denote the attention weight from token to token as , then:

where is the sequence length. This constraint ensures that each token's output is a valid weighted average of the value vectors from all positions. No attention weight can be negative, and the weights form a probability distribution over the sequence.

Tracing the Residual Contribution

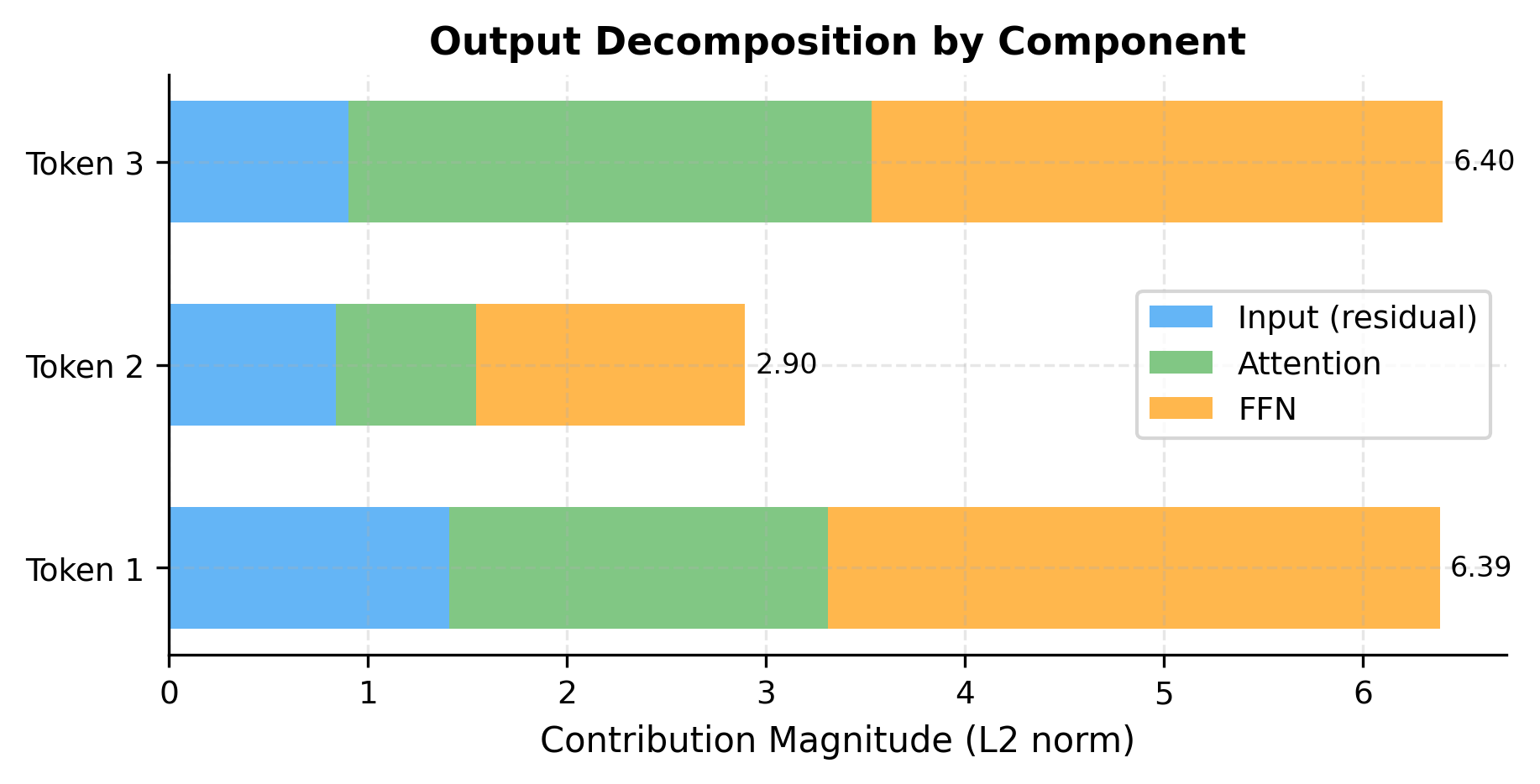

One key insight from residual connections is that the output preserves information from the input. Let's quantify this:

The decomposition reveals how each component contributes to the final representation. Mathematically, the output can be written as:

where:

- : the original input, which passes through both residual connections unchanged

- : the attention sublayer's contribution

- : the FFN sublayer's contribution

The original input remains a substantial part of the output, demonstrating how residual connections preserve information while allowing sublayers to add refinements. This additive structure also explains why gradients flow easily backward through transformer blocks: they can bypass the nonlinear sublayers entirely via the residual paths.

Causal Masking for Decoder Blocks

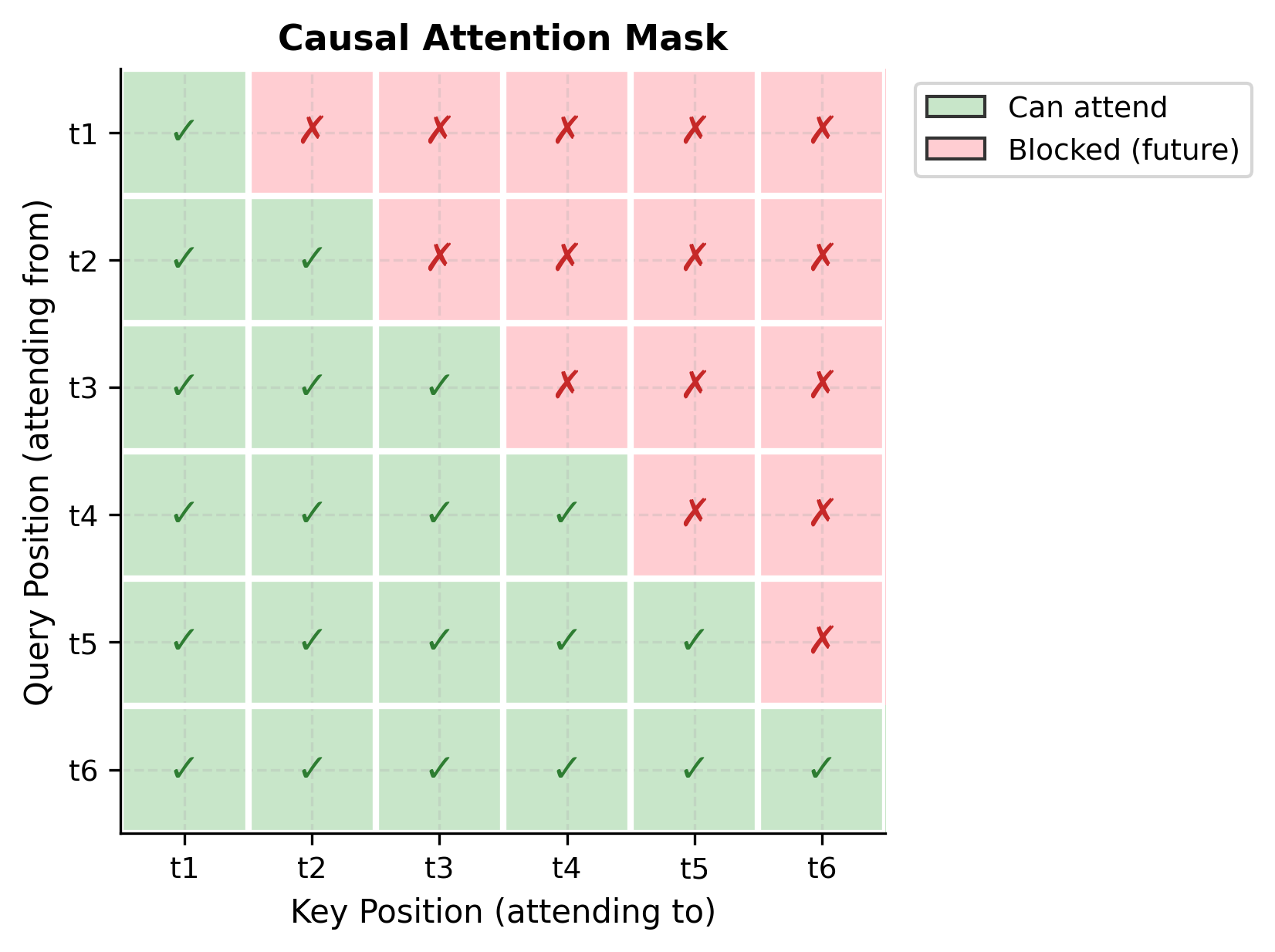

Language models like GPT are autoregressive: they generate tokens one at a time, with each token depending only on previous tokens. This requires causal masking in attention, preventing tokens from attending to future positions.

The causal mask modifies the attention score computation. Recall that attention scores between queries and keys are computed as:

where:

- : the query vector for token at position

- : the key vector for token at position

- : the dimension of the key vectors (used for scaling)

To prevent token from attending to any future token , we add a mask to the scores before applying softmax:

where:

- if (past or current positions, allowed)

- if (future positions, blocked)

After softmax, positions with scores become exactly zero, effectively removing them from the weighted average. The result is a triangular attention pattern where each token can only "see" itself and previous tokens:

Decoder Block Implementation

A decoder block is identical to the standard block, but with causal masking applied during attention:

Stacking Blocks: Building a Complete Model

A transformer model stacks multiple blocks in sequence. The output of one block becomes the input to the next, with each block refining the representations:

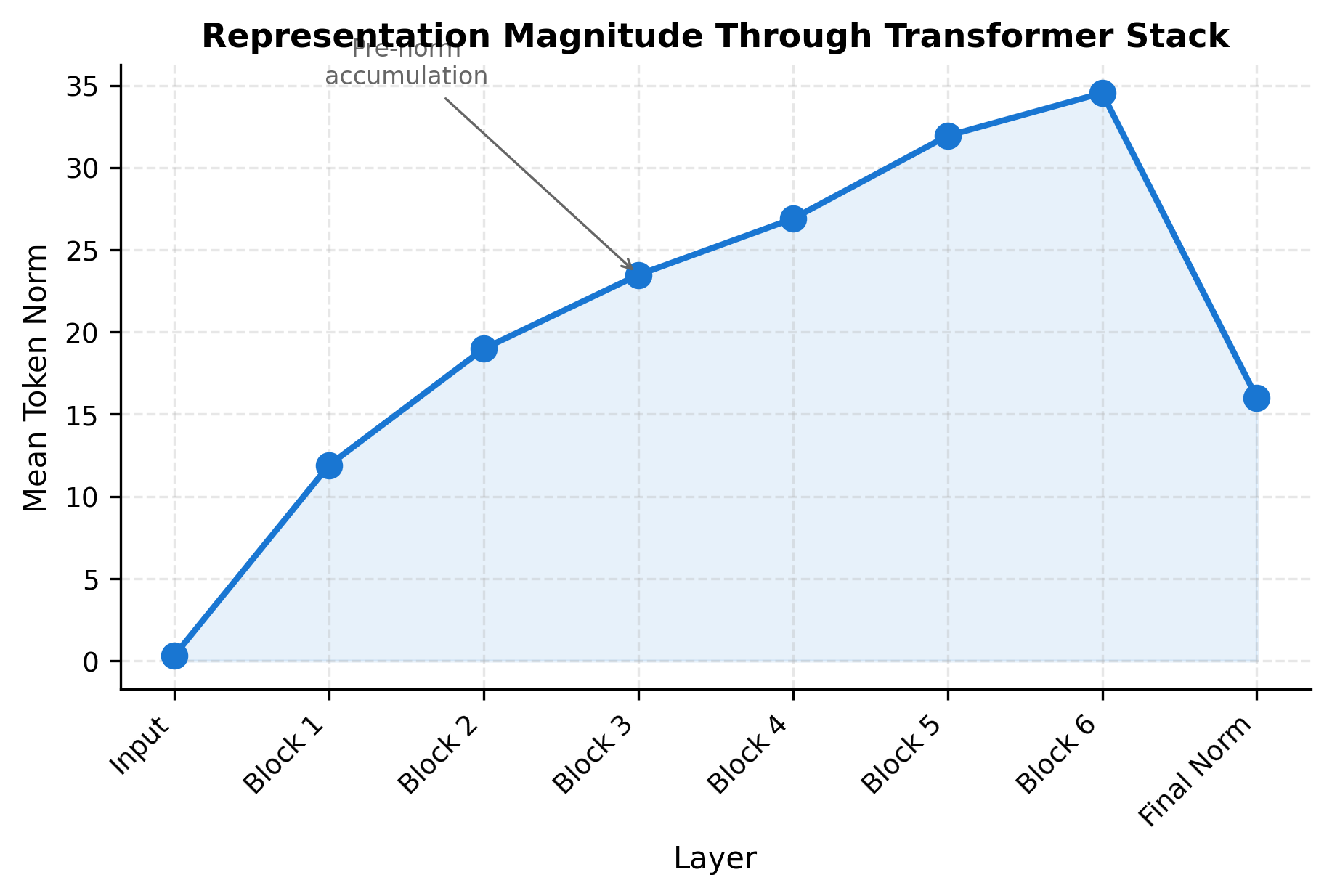

Let's trace how representations evolve through the stack:

The visualization shows how pre-norm architectures allow representation magnitude to grow through the network. Each residual connection adds to the running sum. The final normalization (RMSNorm after all blocks) brings the representations back to a controlled scale before the output layer.

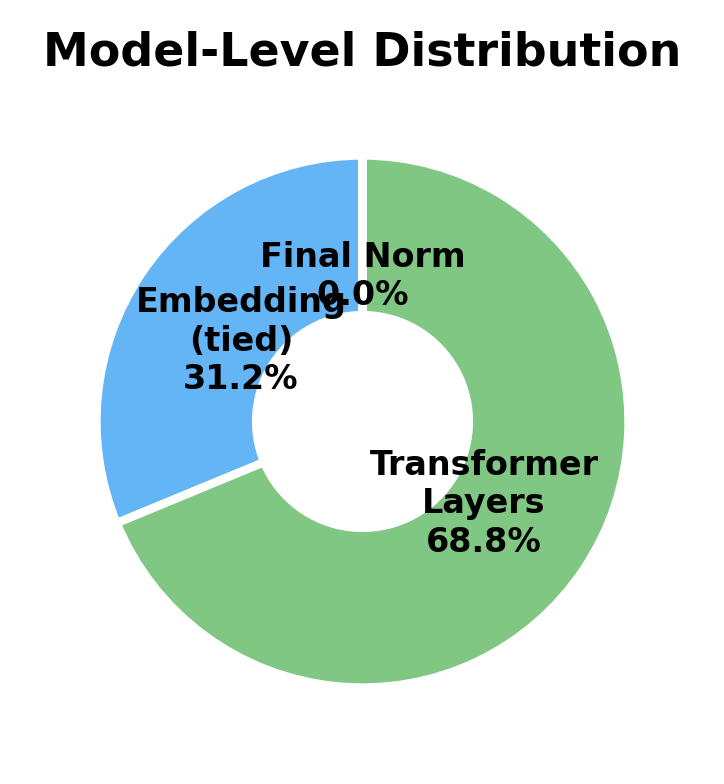

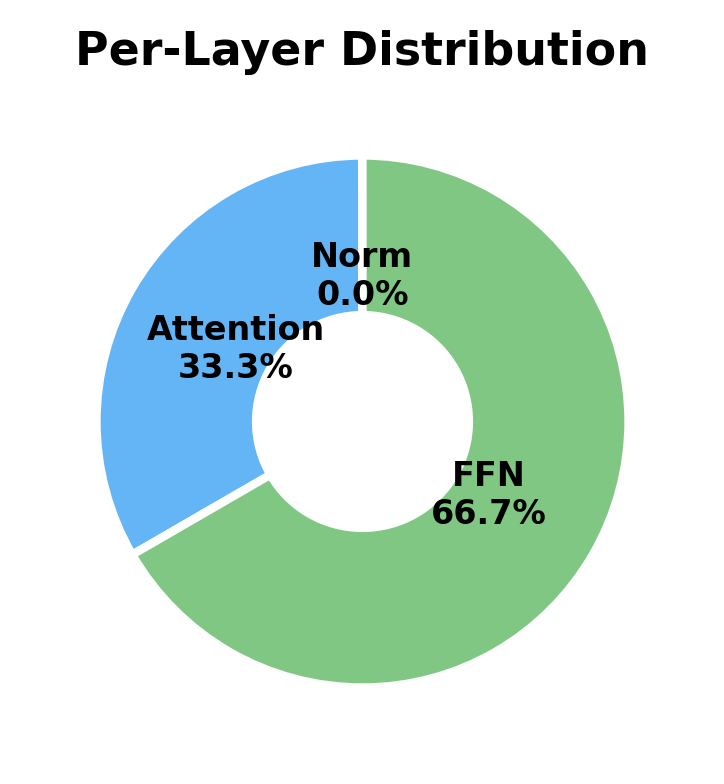

Parameter Breakdown by Component

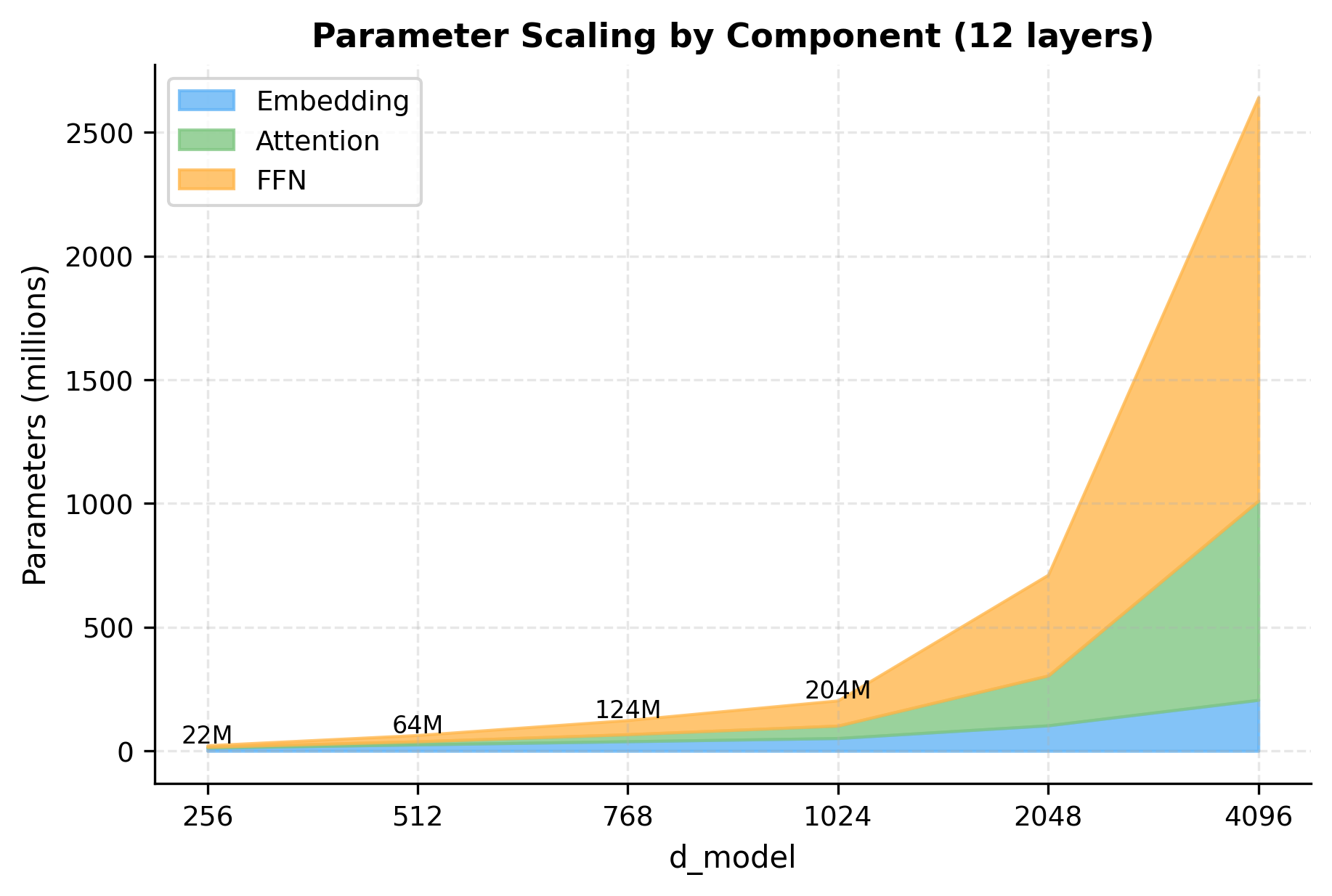

Understanding where parameters live helps with model analysis and optimization. Let's break down a complete model:

The analysis reveals that FFN parameters dominate within each transformer block. Let's quantify this for SwiGLU:

- Attention parameters: (for Q, K, V, and O projections)

- SwiGLU FFN parameters: (for gate, up, and down projections)

With typical SwiGLU expansion (), the FFN has about parameters versus attention's . This is roughly a 2:1 ratio, meaning FFN accounts for about 67% of each block's parameters. At the model level, the embedding layer is also significant: with vocabulary size , the embedding matrix has parameters, which can exceed a single layer's parameters for large vocabularies.

Comparing Block Architectures

Different models use slightly different block configurations. Let's compare the major variants:

The table highlights key design decisions that distinguish architectures:

- Modern models (LLaMA, Mistral) use RMSNorm for efficiency and SwiGLU for improved FFN expressiveness

- BERT is a notable exception, using post-norm placement (it predates the pre-norm stability insights)

- FFN expansion is smaller with gated variants because gating effectively doubles the hidden dimension

To visualize how these architectural choices affect parameter allocation, let's compare parameter counts across different model scales:

The scaling chart reveals an important insight: as models grow larger, the FFN becomes increasingly dominant. At , the FFN accounts for over 80% of transformer layer parameters. This explains why efficiency innovations (like Mixture of Experts) primarily target the FFN component.

Implementation: Production-Ready Block

Let's create a complete, configurable transformer block that supports all the variants we've discussed:

Numerical Stability Considerations

Deep transformers can encounter numerical issues. Several practices help maintain stability:

Mixed precision normalization: Even when using float16 for most computation, normalization should use float32 to prevent underflow when variance is small:

Residual scaling: For very deep networks, scaling residual contributions prevents representation explosion. The intuition is that each residual add accumulates magnitude. After layers without scaling, the representation magnitude can grow as or worse. A common fix is to scale each residual contribution:

where:

- : the input (residual path)

- : the sublayer output

- : a scaling factor, typically for a model with layers

Attention score capping: Large attention logits before softmax can cause numerical issues. Some implementations cap logits:

Limitations and Trade-offs

The standard transformer block design, despite its success, has inherent limitations that shape ongoing research.

Quadratic attention complexity remains the primary bottleneck for long sequences. The attention mechanism computes all pairwise interactions between tokens, resulting in memory and compute for sequence length . Specifically, the attention score matrix has entries, and computing these scores requires dot products. For a 100K token document, this means 10 billion attention scores per layer, quickly becoming impractical. This has driven research into linear attention variants, sparse attention patterns, and hierarchical approaches. Modern architectures like Mistral use sliding window attention to reduce this cost, attending only to a fixed window of previous tokens (giving complexity) while maintaining global context through block-level aggregation.

The FFN bottleneck consumes the majority of parameters and compute for short sequences. With roughly two-thirds of each block's parameters in the FFN, training and inference costs are dominated by these large matrix multiplications. Mixture of Experts (MoE) architectures address this by routing tokens to different expert FFNs, increasing total parameters while keeping per-token compute constant. This allows scaling model capacity without proportionally scaling inference cost.

Position representation in the standard block comes only from positional encodings added to the input. The attention and FFN operations themselves are position-agnostic. While rotary position embeddings (RoPE) inject position information directly into attention, the fundamental architecture still processes positions implicitly rather than explicitly.

Training stability requires careful hyperparameter tuning despite pre-normalization's improvements. Very deep models (50+ layers) still benefit from techniques like residual scaling, careful initialization, and gradient clipping. The interaction between learning rate, batch size, and model depth remains an active area of research.

Despite these limitations, the transformer block's composability has proven highly effective. The same block architecture scales from small research models to GPT-4 class systems, with the primary changes being width, depth, and training data. This modular design enables systematic scaling studies and relatively straightforward implementation of very large models.

Summary

This chapter assembled the components from previous chapters into complete transformer blocks. We implemented both the encoder and decoder variants, traced data flow through concrete examples, and examined the design decisions that distinguish different architectures.

Key takeaways:

-

The two-sublayer pattern: Every transformer block contains attention (for inter-position communication) and FFN (for per-position transformation), each wrapped with normalization and residual connections.

-

Pre-norm is the modern default: Applying normalization before each sublayer creates clean gradient highways through residual connections, enabling stable training of very deep models.

-

RMSNorm replaces LayerNorm: Modern architectures use RMSNorm for its computational efficiency, achieving similar stabilization with fewer operations.

-

SwiGLU FFN improves expressiveness: Gated linear units with SiLU activation (SwiGLU) have become standard in LLaMA-family models, providing better representations than standard GELU FFNs.

-

Causal masking enables autoregressive generation: Decoder blocks use triangular attention masks to prevent tokens from attending to future positions.

-

Parameter distribution matters: FFN parameters dominate (roughly two-thirds of each block), making FFN optimization critical for efficiency.

-

Numerical stability requires care: Mixed-precision normalization, residual scaling, and attention logit capping help maintain stability in deep models.

The transformer block is a modular building block that can be stacked to arbitrary depth. This composability, combined with the attention mechanism's ability to model long-range dependencies, explains why transformers have become the dominant architecture for language modeling and beyond.

Key Parameters

When implementing transformer blocks, these parameters control capacity and efficiency:

-

(model dimension): The embedding dimension that flows through the entire block. Typical values range from 256 (small models) to 12288 (GPT-3 scale). This dimension must be divisible by since each head operates on dimensions.

-

(attention heads): Number of parallel attention mechanisms. More heads enable attending to different types of relationships simultaneously. Common choices are 8, 12, 16, or 32 heads.

-

(FFN hidden dimension): The intermediate dimension of the feed-forward network. For standard FFNs, typically . For SwiGLU, typically (approximately 2.7×) to maintain similar parameter count. The gating mechanism effectively doubles the width, so a smaller explicit expansion compensates.

-

norm_type: Choice between RMSNorm (faster, used in LLaMA/Mistral) and LayerNorm (original, used in GPT-2/BERT). RMSNorm is preferred for new architectures.

-

norm_placement: Pre-norm (normalize before sublayers) or post-norm (normalize after). Pre-norm is standard for modern deep models due to better gradient flow.

-

ffn_type: Standard (two linear layers with activation) or gated (SwiGLU, GeGLU). Gated variants improve expressiveness at similar parameter cost.

-

causal: Whether to apply causal masking in attention. Required for autoregressive language models, disabled for bidirectional encoders like BERT.

-

(normalization epsilon): Small constant (typically to ) added to prevent division by zero in normalization. The RMSNorm formula divides by . Without , a vector of all zeros would cause a division by zero. May need adjustment (e.g., instead of ) for mixed-precision training where numerical precision is lower.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about transformer block assembly.

Comments