Master the encoder-decoder transformer architecture that powers T5 and machine translation. Learn cross-attention mechanism, information flow between encoder and decoder, and when to choose encoder-decoder over other architectures.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Encoder-Decoder Architecture

The previous chapters explored encoder-only and decoder-only transformers as specialized tools: encoders for understanding, decoders for generation. But the original transformer from "Attention Is All You Need" was neither. It combined both components into a unified architecture designed for a specific challenge: transforming one sequence into another where input and output can have completely different lengths, vocabularies, and structures.

Machine translation epitomizes this challenge. "The quick brown fox" has four words, but its German translation "Der schnelle braune Fuchs" also has four, while its Japanese translation might have a completely different structure. Summarization compresses a 1000-word article into a 50-word abstract. Question answering takes a question and a passage, then produces an answer span. These tasks share a common pattern: process an input sequence, understand it deeply, then generate an output sequence that relates to but differs from the input.

The encoder-decoder architecture handles this by dividing labor. The encoder builds rich, bidirectional representations of the input. The decoder generates the output autoregressively, attending both to its own previous outputs and to the encoder's representations through a mechanism called cross-attention. This chapter explores how these components interact, the mathematics of cross-attention, and when encoder-decoder models outperform their encoder-only or decoder-only alternatives.

The Complete Transformer Architecture

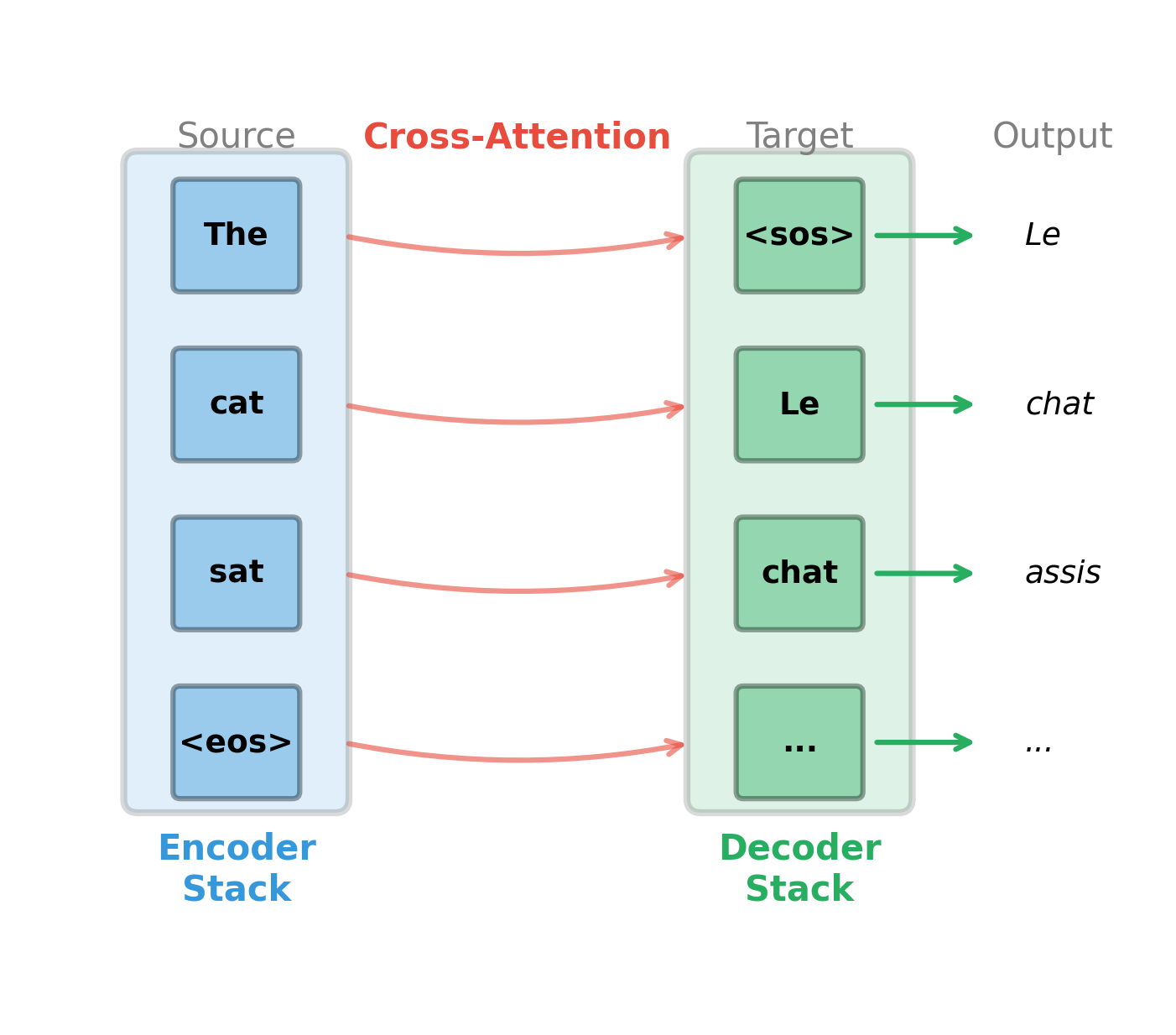

The original transformer architecture consists of three main components that work together to transform input sequences into output sequences:

-

Encoder stack: A series of encoder blocks that process the source sequence bidirectionally, producing contextualized representations for every input position.

-

Decoder stack: A series of decoder blocks that generate the target sequence autoregressively. Each decoder block contains not just self-attention (masked for causality) but also cross-attention to the encoder's output.

-

Cross-attention mechanism: The bridge between encoder and decoder. At each decoder position, cross-attention queries the encoder's representations to gather relevant source information for generation.

This division of labor reflects a fundamental insight: understanding input requires different processing than generating output. The encoder sees everything at once and can use bidirectional context. The decoder must respect temporal ordering since it generates tokens sequentially, but it benefits from full access to the encoder's understanding of the source.

Cross-Attention: The Bridge Between Encoder and Decoder

Consider the challenge of translation. When generating the French word "chat," how does the decoder know to look at the English word "cat" rather than "the" or "sat"? The encoder has produced rich representations of every source word, but the decoder needs a way to selectively access the right information at each generation step.

This is precisely what cross-attention accomplishes. It creates a dynamic, learned connection between the decoder's current state and the encoder's representations, allowing each generated token to "query" the source sequence and retrieve relevant information.

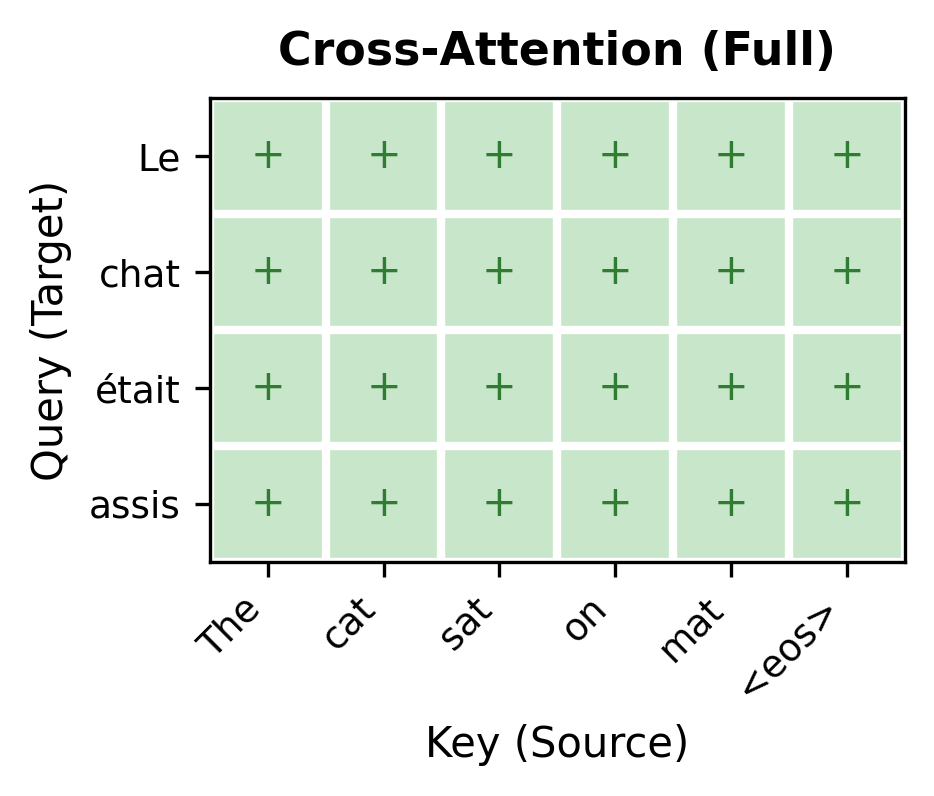

In self-attention, queries, keys, and values all come from the same sequence, with tokens attending to other tokens within their own context. Cross-attention breaks this symmetry: queries come from the decoder (what information am I looking for?), while keys and values come from the encoder (what information is available in the source?). This asymmetry is what enables the decoder to search for and retrieve relevant source information at each generation step.

The Cross-Attention Mechanism

To understand cross-attention mathematically, we need to track two distinct sequences flowing through the architecture. The decoder maintains hidden states for the target positions generated so far. The encoder has already produced its output for all source positions. The key insight is that these sequences can have completely different lengths. We might translate a 10-word English sentence into a 15-word French sentence, or summarize a 1000-token document into 50 tokens.

Cross-attention connects these two sequences through three projections, each serving a distinct purpose:

where:

- : decoder hidden states, one per target position

- : encoder output, one per source position

- : learned projection matrices

- : query matrix with queries from decoder

- : key matrix with keys from encoder

- : value matrix with values from encoder

The asymmetry is crucial: queries come from the decoder, while keys and values come from the encoder. Think of it as the decoder asking questions (queries) and the encoder providing a searchable index (keys) along with the actual information to retrieve (values).

With these projections in place, the attention computation proceeds through three steps. First, we measure compatibility between every decoder query and every encoder key. Then we convert these compatibility scores into attention weights. Finally, we use these weights to compute a weighted sum of encoder values:

Let's unpack each component:

-

Compatibility scores : This matrix multiplication compares each decoder query against all encoder keys. Entry measures how strongly decoder position should attend to encoder position . Higher values indicate stronger relevance.

-

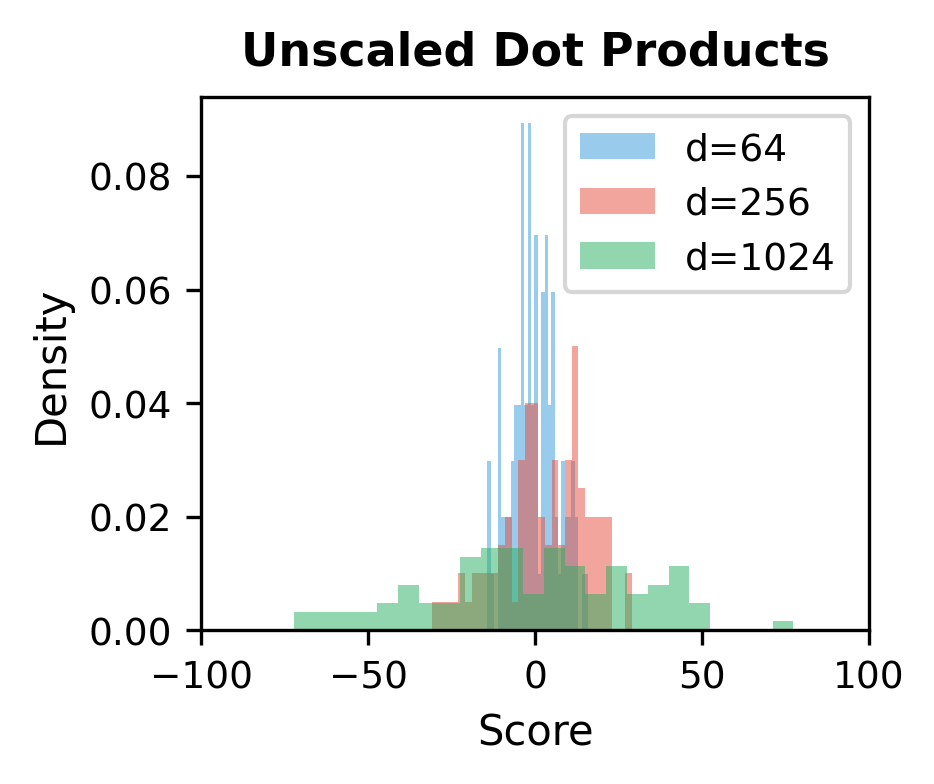

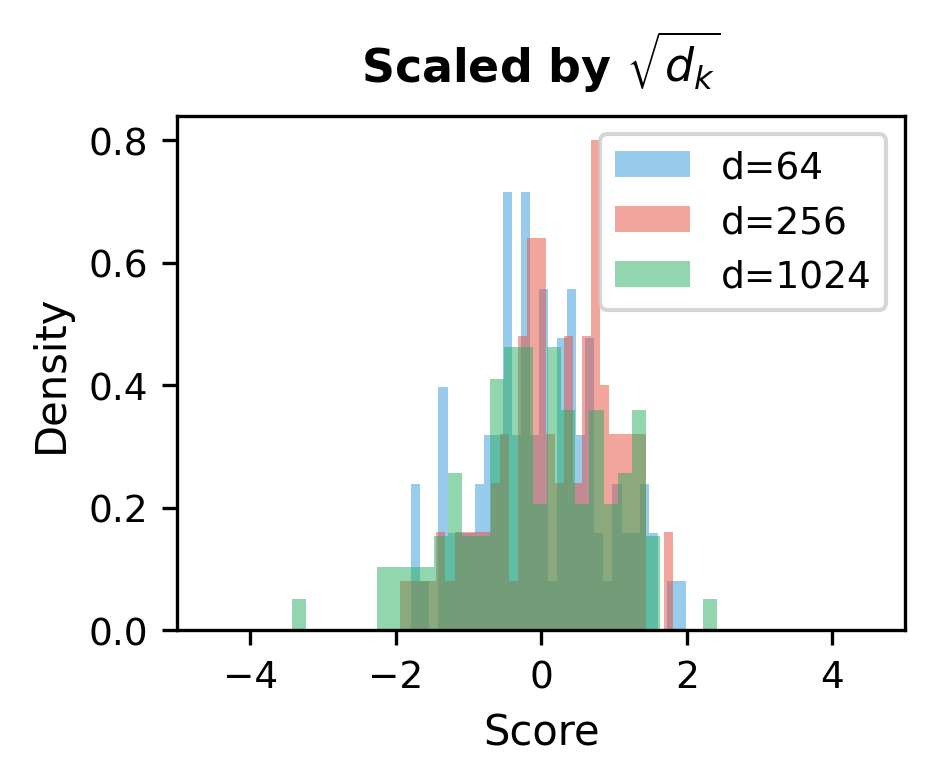

Scaling by : As dimension grows, dot products tend to grow in magnitude, pushing softmax toward extreme values (near 0 or 1). Dividing by keeps gradients stable during training.

-

Softmax normalization: Converts each row of scores into a probability distribution. After softmax, each decoder position has attention weights over the source that sum to 1. These weights represent "how much" of each source position to incorporate.

-

Weighted value sum: The final matrix multiplication retrieves information from the encoder. Each decoder position gets a weighted combination of encoder values, where the weights come from the attention distribution.

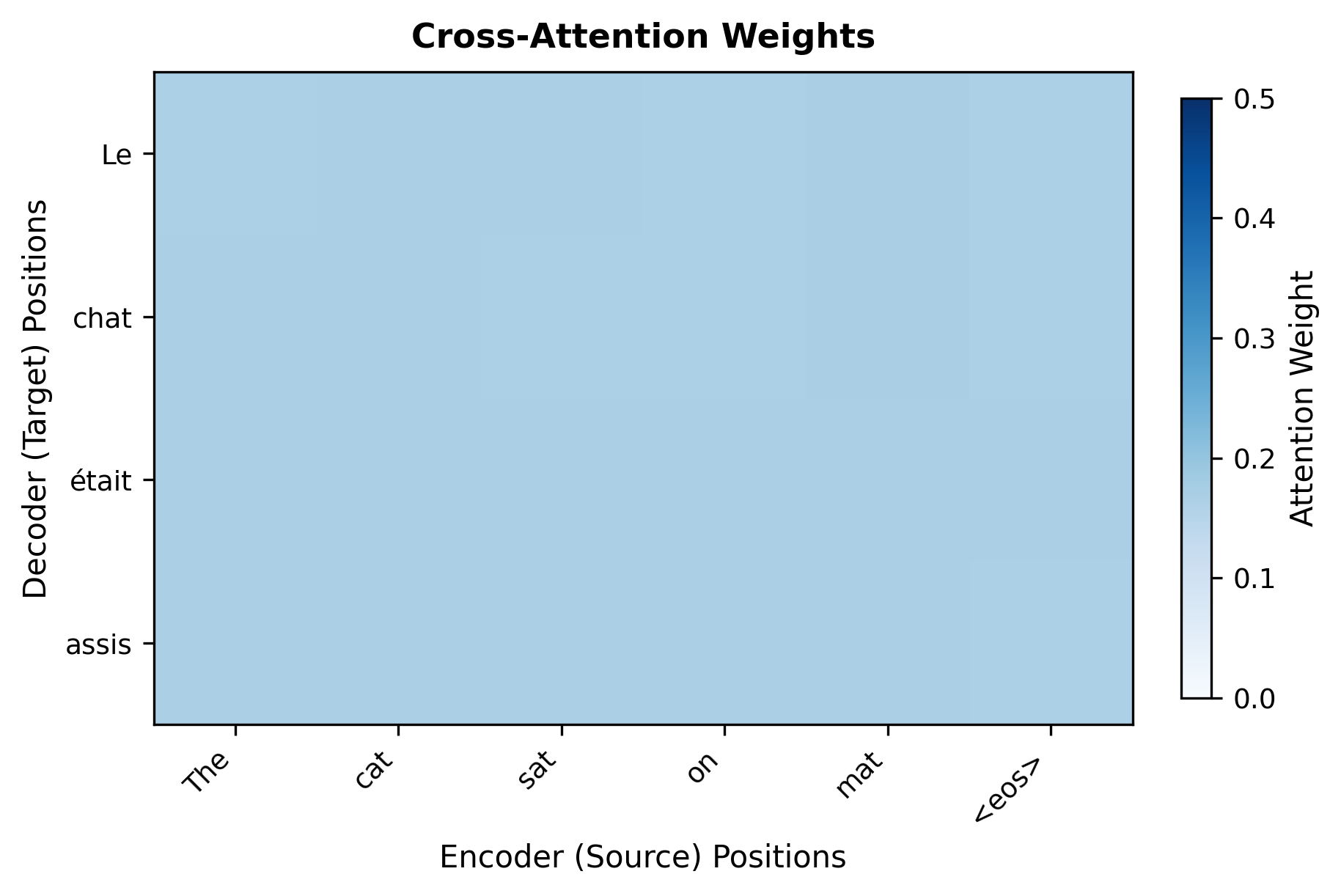

The key geometric insight is that produces an rectangular matrix, not a square matrix. Each of the decoder positions computes attention weights over all encoder positions. This rectangular attention matrix is what distinguishes cross-attention from self-attention and enables sequence-to-sequence transformation between sequences of different lengths.

The output confirms cross-attention produces a rectangular attention weight matrix rather than a square one. Each decoder position computes a probability distribution over all 6 encoder positions, which is why the row sums equal exactly 1.0. This demonstrates the key insight: queries from 4 target positions attend to keys from 6 source positions, creating asymmetric attention that lets each generated word "look at" the entire input sequence.

What Cross-Attention Learns

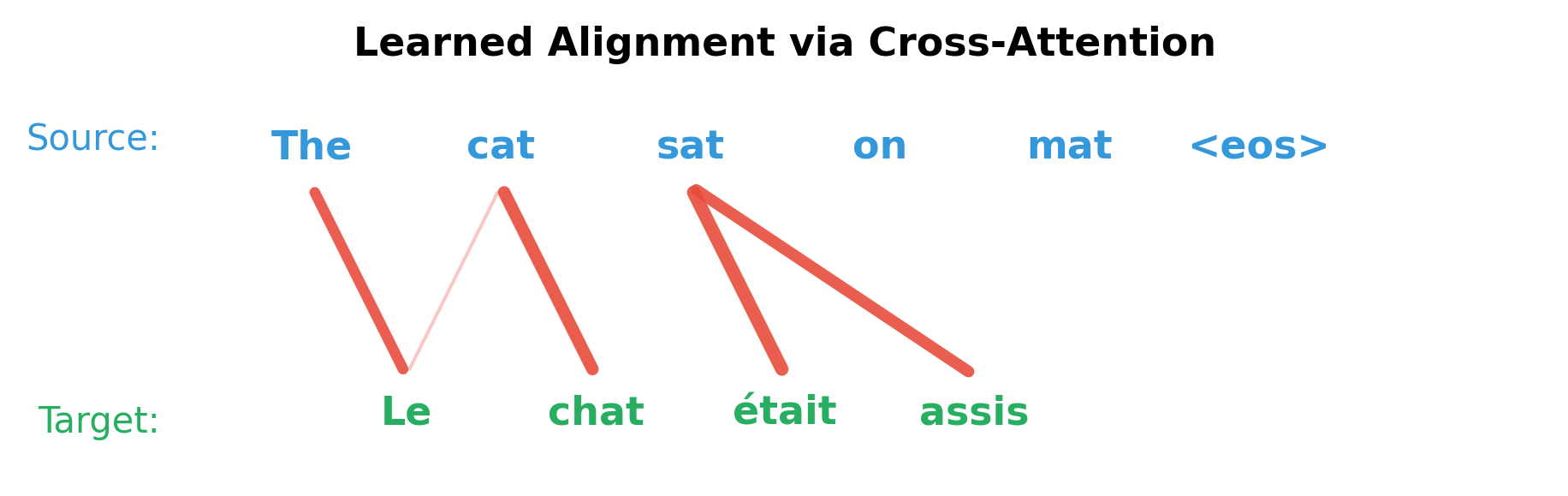

The remarkable property of cross-attention is that it learns meaningful alignments entirely from the end task, without any explicit supervision about which source words correspond to which target words. During training, gradients flow backward from the translation loss, gradually shaping the attention weights to focus on the most relevant source positions.

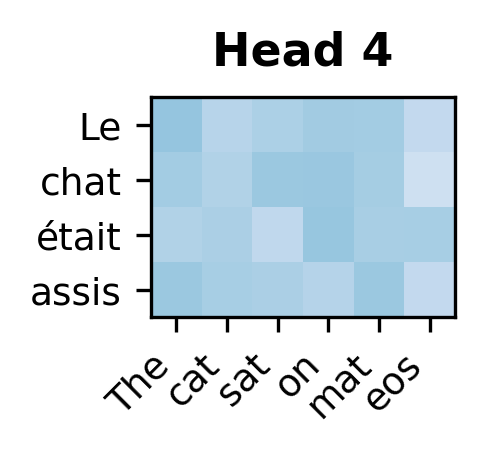

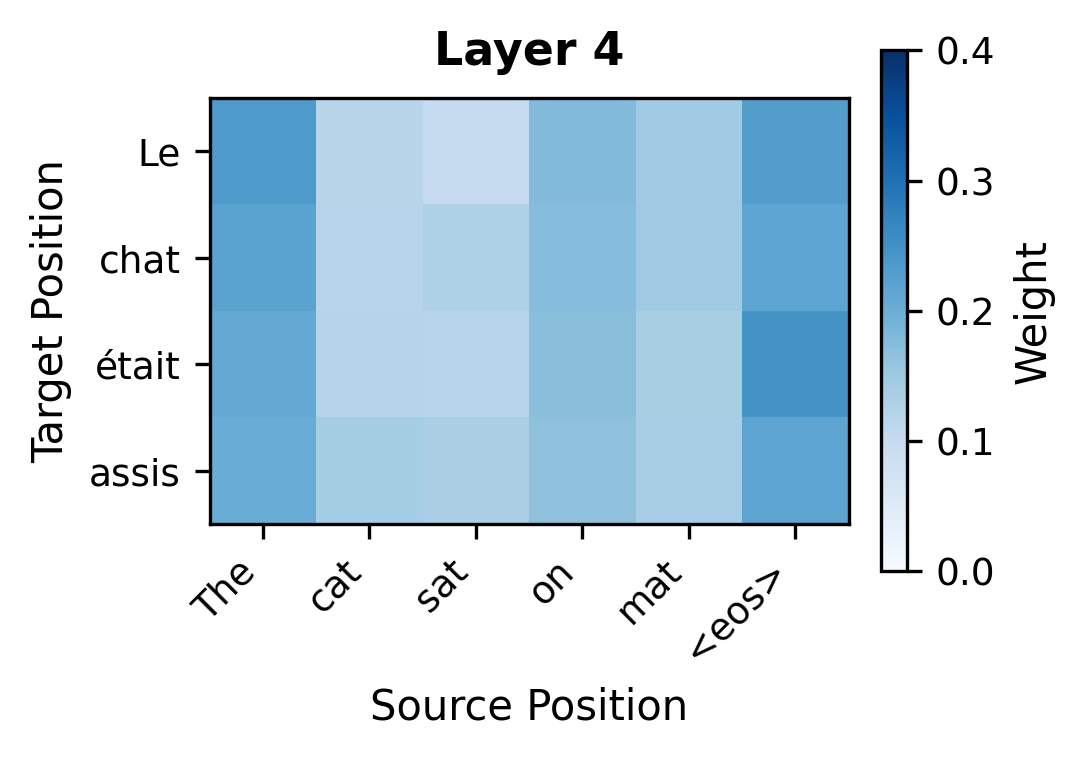

When translating "The cat sat" to "Le chat était assis," a trained model learns attention patterns that reflect linguistic structure:

- When generating "chat" (French for cat), attend strongly to "cat" in the source, a direct lexical correspondence

- When generating "était assis" (was sitting), attend primarily to "sat", capturing a one-to-many mapping where one English word expands to two French words

- When generating "Le," attend to context that determines grammatical gender, since the model learns that "cat" requires the masculine article

This learned alignment emerges from the training signal alone. The model discovers through thousands of examples that attending to the right source positions helps produce correct translations. In effect, cross-attention replaces the explicit alignment models used in pre-neural statistical machine translation, while being more flexible since it can capture soft, distributed alignments rather than hard one-to-one correspondences.

Anatomy of a Decoder Block with Cross-Attention

Understanding the decoder block requires recognizing that it must accomplish two distinct but interrelated tasks: it must generate coherent, grammatical output (like any language model), while also staying faithful to the source sequence (which distinguishes translation from free generation). The architecture addresses these requirements through a carefully ordered sequence of three sublayers.

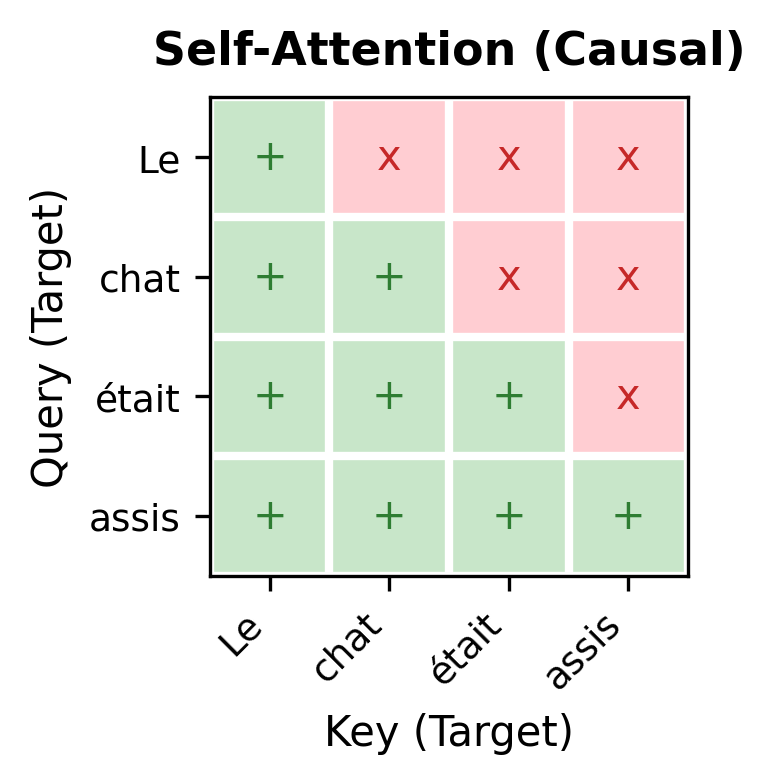

Sublayer 1: Masked Self-Attention. The decoder first attends to its own previous outputs. When generating the fourth target word, it considers the first three words it has already produced. This builds a representation of the generation context so far. The attention is masked (causal) to prevent the decoder from seeing future tokens, which is essential for autoregressive generation where we produce one token at a time.

Sublayer 2: Cross-Attention. Armed with context about what it has generated, the decoder now queries the encoder. This is where source information enters. The decoder's refined representation serves as queries, and the encoder's output provides keys and values. The cross-attention sublayer answers: "Given what I've generated so far, what source information is relevant for the next token?"

Sublayer 3: Feed-Forward Network. Finally, a position-wise FFN applies nonlinear transformation to each position independently. This adds representational capacity and allows the model to process the combined information from self-attention and cross-attention.

The ordering matters: self-attention establishes generation context, cross-attention enriches it with source information, and the FFN transforms the result. Each sublayer includes residual connections and layer normalization, ensuring stable gradient flow through deep stacks.

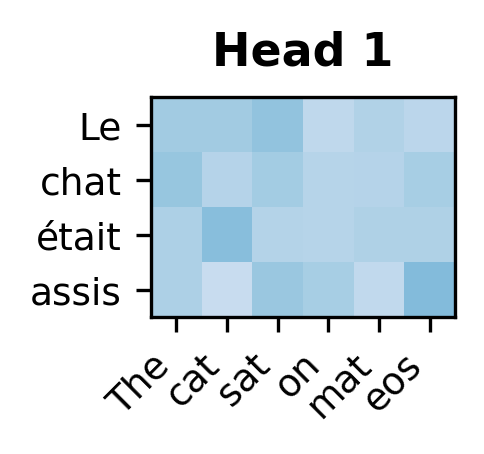

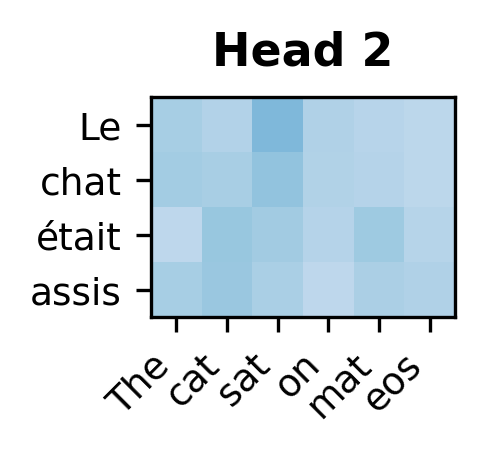

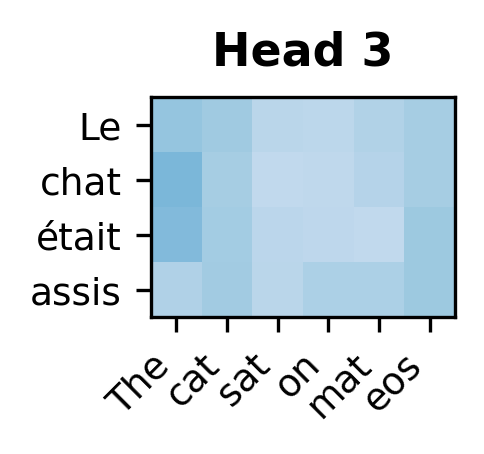

The decoder block successfully processes target embeddings while attending to encoder output. The cross-attention weights have shape (n_heads, tgt_len, src_len), showing that each of the 8 attention heads learns independent patterns for how target positions query source positions. Weight sums of 1.0 across each target position confirm proper softmax normalization. The output maintains the same shape as the input (tgt_len, d_model), ready to be passed to subsequent decoder layers.

Each attention head learns distinct patterns for how target positions attend to source positions. Some heads may specialize in local alignment while others capture longer-range dependencies.

Building the Complete Encoder-Decoder Transformer

With the individual components understood (cross-attention for source access, masked self-attention for autoregressive generation, and feed-forward networks for transformation), we can now assemble the complete architecture.

The full encoder-decoder transformer stacks multiple blocks on each side. The encoder builds increasingly abstract representations of the source through successive bidirectional self-attention layers. The decoder mirrors this depth, with each layer first refining its generation context (self-attention), then consulting the encoder's final output (cross-attention), and finally applying nonlinear transformation (FFN).

A crucial efficiency emerges from this design: the encoder processes the source sequence exactly once. Its output is then reused by every decoder layer at every generation step. When generating a 50-word summary, the decoder queries the same encoder representations 50 times, once per generated token, without recomputing them.

The complete encoder-decoder transformer successfully processes source and target sequences. The encoder compresses the 6-token source into 256-dimensional representations, which the decoder queries through cross-attention while generating 4 target tokens. Each decoder layer produces cross-attention weights of shape (8, 4, 6), representing how 8 heads × 4 target positions attend to 6 source positions. The final logits of shape (4, 12000) give probability distributions over the target vocabulary for each generated position.

Information Flow in Encoder-Decoder Models

The encoder-decoder architecture's power comes from a carefully designed asymmetry in how information flows. The encoder and decoder process their sequences differently, and cross-attention creates a one-way bridge between them.

Encoder: Bidirectional Processing

The encoder enjoys complete freedom: every source position can attend to every other source position through bidirectional self-attention. When encoding "The cat sat on the mat," the representation for "cat" incorporates context from both directions: "The" before it and "sat on the mat" after it. This bidirectional view is essential for understanding meaning, since words often depend on both their left and right context for disambiguation.

The encoder runs in one pass, processing all source positions simultaneously (in parallel). By the time the decoder begins, the encoder has built rich, contextualized representations that capture the full meaning of each source word.

Decoder: Causal Self-Attention + Full Cross-Attention

The decoder operates under two different attention regimes simultaneously, and understanding this distinction is crucial:

Self-attention is causal (masked). When the decoder generates the third target word, it can only attend to the first and second target words, never to future tokens that haven't been generated yet. This respects the autoregressive nature of generation: we can't condition on outputs we haven't produced.

Cross-attention is unrestricted. When generating that same third target word, the decoder can attend to any source position, including positions near the end of the source sequence. There's no masking here because the source is fully available; it was processed by the encoder before generation began.

This asymmetry enables a powerful capability: the decoder can "look ahead" in the source sequence while generating sequentially in the target. When translating "The cat sat" to "Le chat était assis," the decoder can attend to "sat" when generating "Le", which is useful for determining that the sentence structure will require masculine agreement.

Layer-by-Layer Refinement

Both encoder and decoder stack multiple layers, and depth enables increasingly abstract representations. But the pattern of refinement differs between them.

Each encoder layer refines source representations by allowing every position to gather information from all other positions. Early layers might resolve local ambiguities; later layers build higher-level semantic representations. A 6-layer encoder gives each word 6 opportunities to absorb context from the entire source.

Each decoder layer follows the three-step sequence we saw earlier:

- Refine target representations based on target context so far (masked self-attention)

- Enrich target representations with relevant source information (cross-attention)

- Apply nonlinear transformation (FFN)

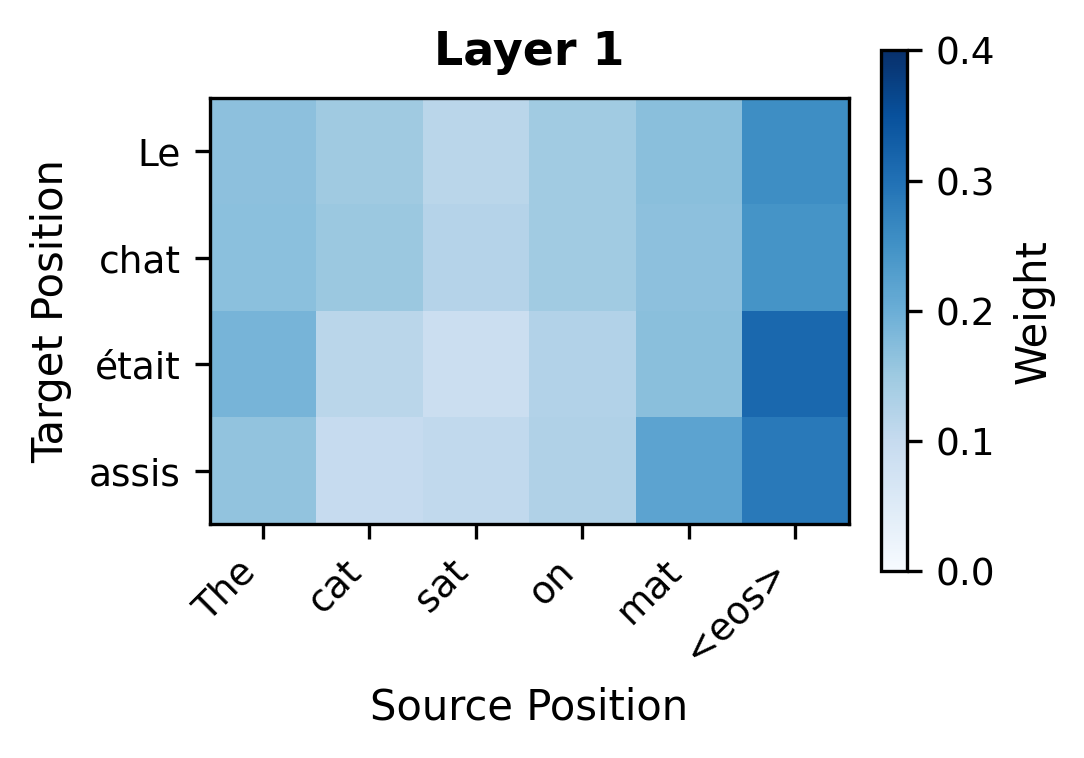

The critical design choice is that cross-attention happens at every decoder layer, not just once. This means source information can influence target representations repeatedly, at multiple levels of abstraction. Early decoder layers might capture lexical correspondences, such as "chat" attending to "cat." Later decoder layers might capture more abstract semantic relationships, like attending to source context that helps determine verb tense or article agreement.

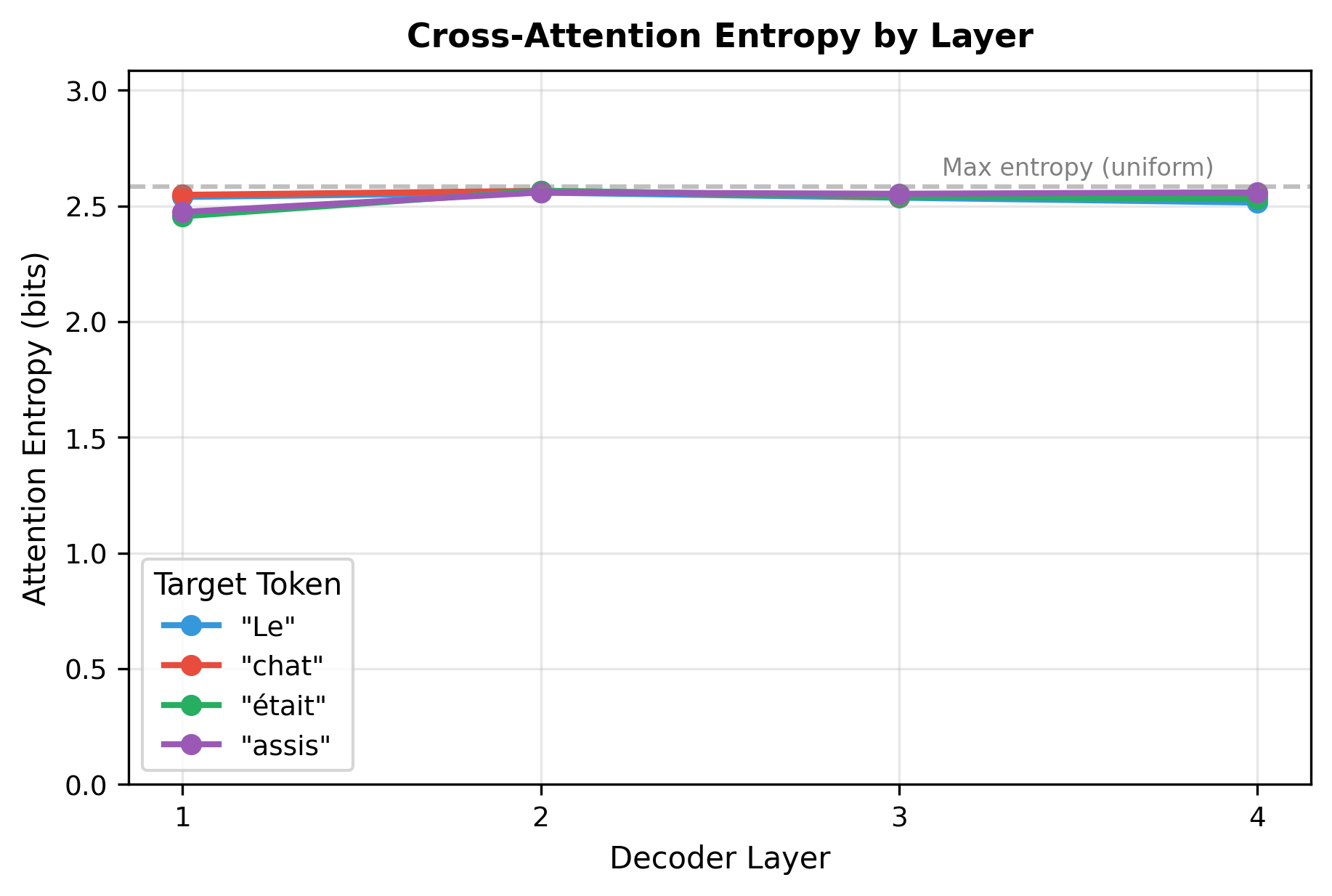

To quantify how attention patterns change across layers, we can measure the entropy of each target position's attention distribution. Higher entropy indicates diffuse attention (looking at many source positions), while lower entropy indicates focused attention (concentrating on a few positions).

T5: Text-to-Text with Encoder-Decoder

T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) exemplifies the encoder-decoder paradigm at scale. Google's T5 treats every NLP task as a text-to-text problem: given some input text, generate some output text. Translation becomes "translate English to German: The cat sat" → "Die Katze saß." Summarization becomes "summarize: [long article]" → "[short summary]." Even classification becomes "sentiment positive or negative: This movie was great" → "positive."

T5 uses the standard encoder-decoder transformer architecture with relative position encodings. Both encoder and decoder share the same vocabulary and can be scaled independently. T5-Base has 220M parameters, T5-Large has 770M, T5-3B has 3 billion, and T5-11B has 11 billion parameters.

T5 Design Choices

T5 made several key architectural decisions that influenced subsequent encoder-decoder models:

-

Relative position encodings: Instead of absolute position embeddings, T5 uses relative position biases in attention, allowing better generalization to different sequence lengths.

-

Pre-norm architecture: Layer normalization applied before each sublayer rather than after, matching modern practice.

-

Shared embeddings: The same embedding matrix is used for both encoder and decoder, as well as for the output projection (tied embeddings).

-

Simplified layer norm: Removes the bias term and centering from standard layer normalization, keeping only learnable scale parameters.

The T5 family spans three orders of magnitude in parameter count, from 60M to 11B. The scaling pattern reveals interesting design choices: layer count increases modestly (6 → 12 → 24) while hidden dimensions and especially feed-forward dimensions grow substantially. T5-11B achieves its massive scale primarily through a 65,536-dimensional FFN, 16× larger than T5-Base. The number of attention heads also scales with model size, with T5-11B using 128 heads to maintain fine-grained attention patterns at scale.

Why Encoder-Decoder for T5?

Google explored various architectures in the T5 paper and found encoder-decoder models outperformed decoder-only models on most tasks when controlled for computational budget. The encoder's ability to process input bidirectionally proved especially valuable for:

- Tasks with long inputs: Summarization, question answering over passages

- Tasks requiring input understanding: Classification, span extraction

- Tasks with complex input-output alignment: Translation, structured generation

Decoder-only models excelled primarily at pure generation tasks without structured input. For the broad range of NLP tasks T5 targets, the encoder-decoder architecture provided better overall performance.

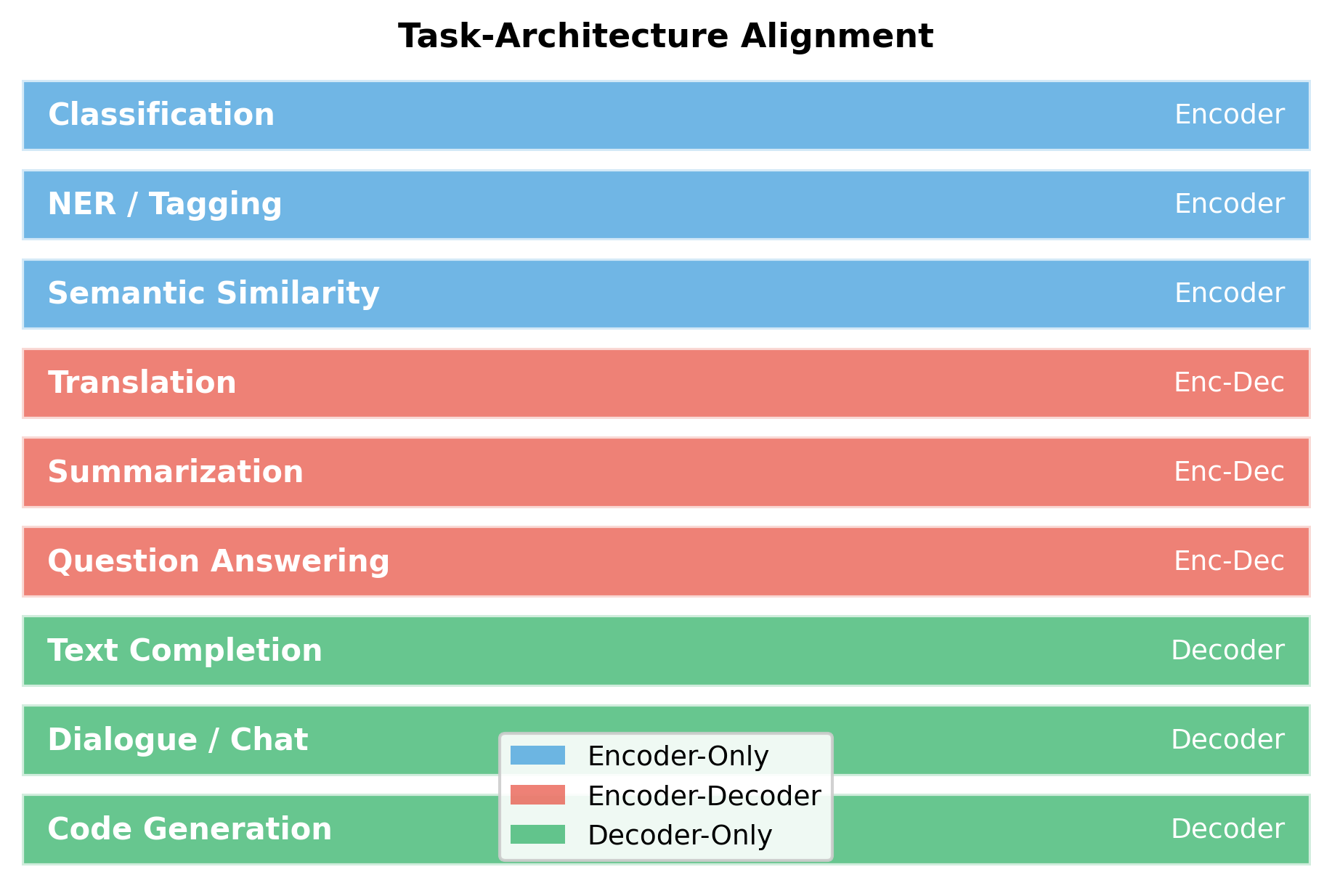

When to Use Encoder-Decoder Architecture

The choice between encoder-only, decoder-only, and encoder-decoder architectures depends on the task structure. Here's a framework for deciding:

Use Encoder-Decoder When:

- Input and output are both sequences but structurally different: Translation, summarization, style transfer

- The input requires deep understanding before generation begins: Question answering, data-to-text

- Input-output alignment is complex and non-monotonic: The output may reorder, add, or drop information from the input

- The input is much longer than the output: Summarization, where encoding the input once and referencing it repeatedly is more efficient than including it in the decoder context

Use Decoder-Only When:

- Generation is the primary goal: Creative writing, code generation, conversational AI

- The task is primarily about extending or continuing: Completion, elaboration

- Prompt engineering is the primary interface: The input is a short prompt, not a structured document to be transformed

- Simplicity and scale are priorities: Decoder-only models are architecturally simpler and have dominated recent scaling efforts

Use Encoder-Only When:

- No generation is required: Classification, NER, extractive QA

- The task is fundamentally about understanding: Semantic similarity, sentiment analysis

- Efficiency at inference is critical: Encoders require one forward pass, not autoregressive generation

Implementing Encoder-Decoder Generation

At inference time, the encoder processes the source sequence once. The decoder then generates the target sequence autoregressively, querying the cached encoder output at each step.

The generation demonstrates the encoder-decoder inference pattern: the encoder runs once to produce cached representations, then the decoder generates tokens autoregressively while querying that cache through cross-attention. The generated sequence (10 tokens) differs in length from the source (6 tokens), showing how the architecture naturally handles variable-length outputs. This "encode once, decode many times" pattern is particularly efficient for tasks like summarization, where a long input document is encoded once and then referenced repeatedly during output generation.

The generation process highlights the efficiency advantage of encoder-decoder models for tasks with long inputs. The encoder processes a 1000-word document once. The decoder then generates a 50-word summary, accessing the encoded document through cross-attention at each of the 50 generation steps. Compare this to a decoder-only approach that would need to include the full document in context at every step.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Encoder-decoder models offer powerful capabilities for sequence transformation, but they come with trade-offs that affect when and how to use them.

Computational Considerations

The encoder and decoder are distinct modules that must be trained and deployed together. This doubles the parameter count compared to using just an encoder or decoder of the same size. For translation between N languages, you need either N(N-1) models (one per direction) or a multilingual model that handles all directions.

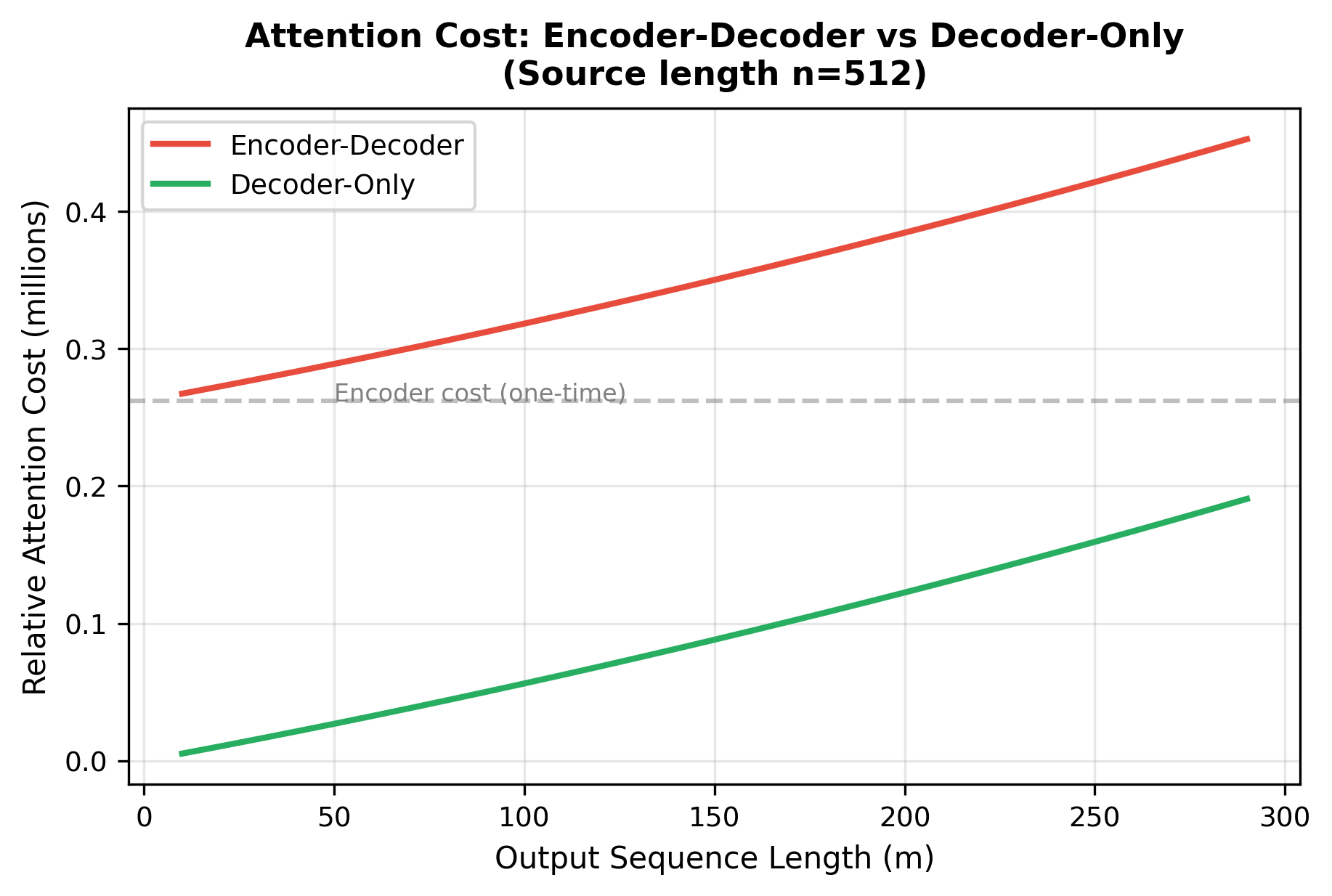

Cross-attention adds computational overhead. Each decoder layer computes attention over the full encoder output, adding operations per layer, where:

- : the target sequence length (number of tokens generated so far)

- : the source sequence length (number of encoder positions)

- : the complexity of computing attention scores between all decoder-encoder position pairs

For long source sequences, this cross-attention cost can dominate computation, especially as the decoder generates many tokens.

The Rise of Decoder-Only Models

Despite encoder-decoder models' strong performance on structured tasks, recent trends have favored decoder-only architectures at scale. GPT-4, Claude, and Llama are all decoder-only. Several factors drive this:

- Simplicity: One architecture handles both understanding and generation

- Scaling: Easier to scale one component than two

- Flexibility: The same model handles diverse tasks through prompting

- Training efficiency: Next-token prediction provides dense supervision

However, encoder-decoder models remain valuable for production systems where task structure is fixed. Translation services, summarization APIs, and document processing pipelines often use encoder-decoder models because the structured input-output relationship benefits from specialized processing.

When Encoder-Decoder Wins

The encoder-decoder architecture offers clear advantages in specific scenarios:

- Repeated access to input: When the decoder needs to reference the input multiple times during generation, encoding once is more efficient than reprocessing.

- Length mismatch: When output is much shorter than input (summarization) or much longer (elaboration), the asymmetric architecture is natural.

- Non-monotonic alignment: When output order differs from input order, cross-attention learns the complex alignment better than a decoder trying to handle both tasks.

Summary

The encoder-decoder transformer architecture combines the strengths of bidirectional encoding and autoregressive decoding through the cross-attention mechanism. Key takeaways:

-

Cross-attention enables the decoder to query encoder representations, creating a bridge between source understanding and target generation. Queries come from the decoder, keys and values from the encoder.

-

Three-sublayer decoder blocks include masked self-attention for autoregressive generation, cross-attention for source access, and a feed-forward network for transformation.

-

Information flow differs between components: the encoder sees bidirectional context, the decoder's self-attention is causal, but cross-attention provides unrestricted access to the source.

-

T5 and similar models demonstrate the architecture's versatility, treating diverse NLP tasks as text-to-text problems.

-

Architecture choice depends on task structure: encoder-decoder for sequence-to-sequence transformation, decoder-only for generation, encoder-only for understanding.

The encoder-decoder paradigm from "Attention Is All You Need" remains the foundation for many production NLP systems, particularly those with structured input-output relationships. While decoder-only models dominate current scaling efforts, encoder-decoder models continue to excel at tasks that benefit from dedicated encoding and controlled generation.

Key Parameters

When configuring encoder-decoder transformers, these parameters most directly impact model capacity and performance:

-

d_model (model dimension): The dimensionality of representations in both encoder and decoder. Must be divisible by n_heads. Typical values: 256 (small), 512 (base), 768 (large), 1024+ (very large).

-

n_heads (attention heads): Number of parallel attention heads in both self-attention and cross-attention. Usually chosen so d_model / n_heads = 64 or 128. More heads enable diverse attention patterns.

-

n_encoder_layers / n_decoder_layers: Depth of encoder and decoder stacks. Often equal (6 layers each in original transformer, 12 in T5-Base). Deeper models learn more complex transformations.

-

d_ff (feed-forward dimension): Hidden dimension in FFN sublayers. Conventionally 4 × d_model. The FFN accounts for most parameters in each layer.

-

src_vocab_size / tgt_vocab_size: Source and target vocabulary sizes. May be equal (shared vocabulary) or different (separate vocabularies). Larger vocabularies reduce sequence length but increase embedding parameters.

-

max_seq_len: Maximum supported sequence length. Affects position embedding size and memory requirements. Original transformer used 512; modern models support 2048-8192+.

-

temperature (generation): Controls randomness during sampling. Lower values (0.7) produce more focused output; higher values (1.2) increase diversity. Affects generation quality and creativity trade-off.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about the encoder-decoder transformer architecture and cross-attention.

Comments