Learn how constrained decoding forces language models to generate valid JSON, SQL, and regex-matching text through token masking and grammar-guided generation.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Constrained Decoding

Language models generate text by sampling from a probability distribution over the vocabulary at each step. This works well for creative writing, conversational responses, and open-ended generation. But what happens when you need the model to produce structured output, like valid JSON, SQL queries, or text matching a specific pattern? Standard sampling offers no guarantees. The model might produce syntactically invalid JSON, hallucinate field names, or ignore your carefully specified schema.

Constrained decoding solves this problem by modifying the generation process itself. Instead of allowing the model to choose freely from all tokens at each step, we restrict it to tokens that keep the output on a valid path. The model still leverages its learned distributions, but we guide it toward outputs that satisfy our structural requirements. This technique has become essential for building reliable AI systems that integrate with existing software infrastructure.

Why Unconstrained Generation Fails

Before diving into solutions, let's understand why asking a model nicely to follow a format often doesn't work. Language models learn patterns from training data, including the patterns of JSON, XML, and other structured formats. They can often produce valid structured output. But "often" isn't good enough for production systems.

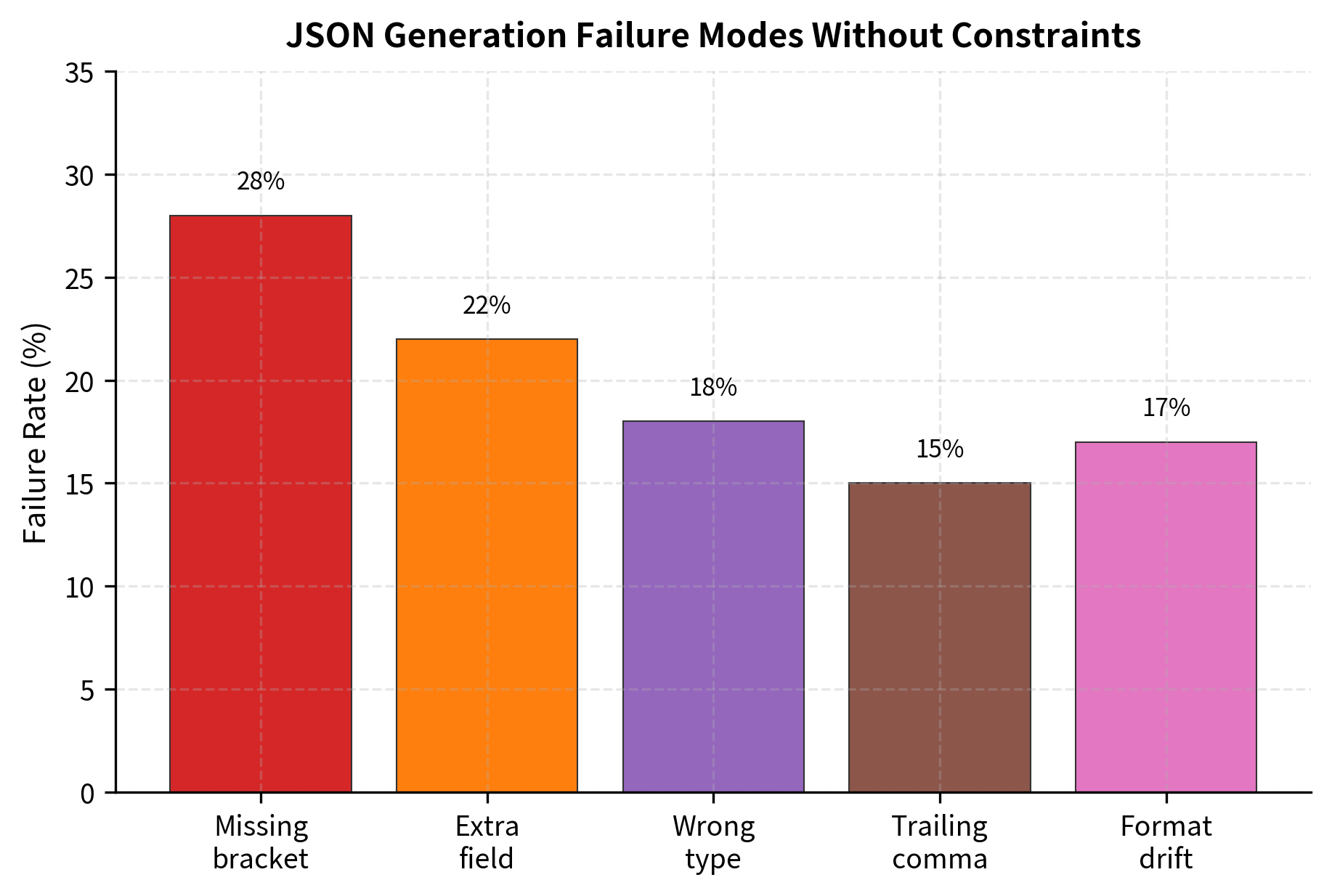

Consider a simple scenario: you want the model to output a JSON object with specific fields. Even with careful prompting, several failure modes emerge:

- Syntax errors: Missing commas, unmatched brackets, trailing commas that violate strict JSON

- Schema violations: Extra fields the model invented, missing required fields, wrong data types

- Encoding issues: Unescaped special characters, invalid Unicode sequences

- Format drift: The model starts with JSON but drifts into natural language explanation

These failures aren't bugs in the model. They reflect the fundamental nature of autoregressive generation: each token is sampled independently given the context, with no mechanism to enforce global constraints. The model doesn't "know" it needs to close a brace three tokens from now. Constrained decoding adds that knowledge.

The Core Idea: Token Masking

To understand constrained decoding, we need to think carefully about what happens at each generation step. A language model produces a probability distribution over its entire vocabulary, perhaps 50,000 tokens or more. From this distribution, we sample a single token to continue the sequence. The challenge is that the model has no built-in knowledge of our structural requirements. It might assign high probability to tokens that would break our desired format.

The solution is simple: before sampling, we modify the distribution to exclude impossible choices. This is called token masking, and it forms the foundation of all constrained decoding techniques.

Building Intuition

Consider a concrete scenario. You're generating JSON, and so far you've produced {"name": "Alice". What tokens could come next in valid JSON?

- A comma

,to add another field - A closing brace

}to end the object

What tokens would break the JSON?

- A letter like

aorb(no string delimiter) - A number without a preceding colon

- Another opening brace

{(not a valid position)

The model might assign probability to any of these tokens based on patterns it learned during training. Our job is to intercept the sampling process and remove the invalid options before the model can choose them.

Token masking modifies the probability distribution at each generation step by setting the probability of invalid tokens to zero (or negative infinity in log-space). The remaining valid tokens are renormalized to form a proper probability distribution for sampling.

The Constrained Generation Process

At each step of generation, given the tokens produced so far , we follow a four-step process:

- Query the model: Compute the probability distribution over the full vocabulary

- Evaluate constraints: Determine which tokens are valid given our structural requirements and the current partial output

- Mask invalid tokens: Set the probability of every invalid token to zero

- Renormalize and sample: Adjust the remaining probabilities to sum to 1, then sample

The critical question is: how do we "adjust" the probabilities in step 4? We can't simply zero out invalid tokens and sample, because the remaining probabilities no longer form a valid distribution (they don't sum to 1). We need a principled approach.

The Mathematical Formulation

Let denote the set of tokens that satisfy our constraint given the current context. We want to construct a new probability distribution, , that:

- Assigns zero probability to invalid tokens

- Preserves the relative ranking among valid tokens

- Forms a proper probability distribution (sums to 1)

The solution is to divide each valid token's probability by the total probability mass of all valid tokens:

where:

- : the candidate token at generation step

- : the original probability assigned by the model to token

- : the set of tokens that satisfy the constraint given the current context

- : the sum of probabilities over all valid tokens, serving as the normalization constant

Why This Formula Works

The formula accomplishes exactly what we need through a technique called renormalization. Let's trace through why each component matters.

The numerator preserves the model's original preference for token . If the model strongly preferred this token before masking, it will still be favored afterward.

The denominator is the total probability mass that was originally assigned to all valid tokens. By dividing by this sum, we scale up the valid probabilities so they sum to 1.

The conditional structure ensures invalid tokens get exactly zero probability. They cannot be sampled, period.

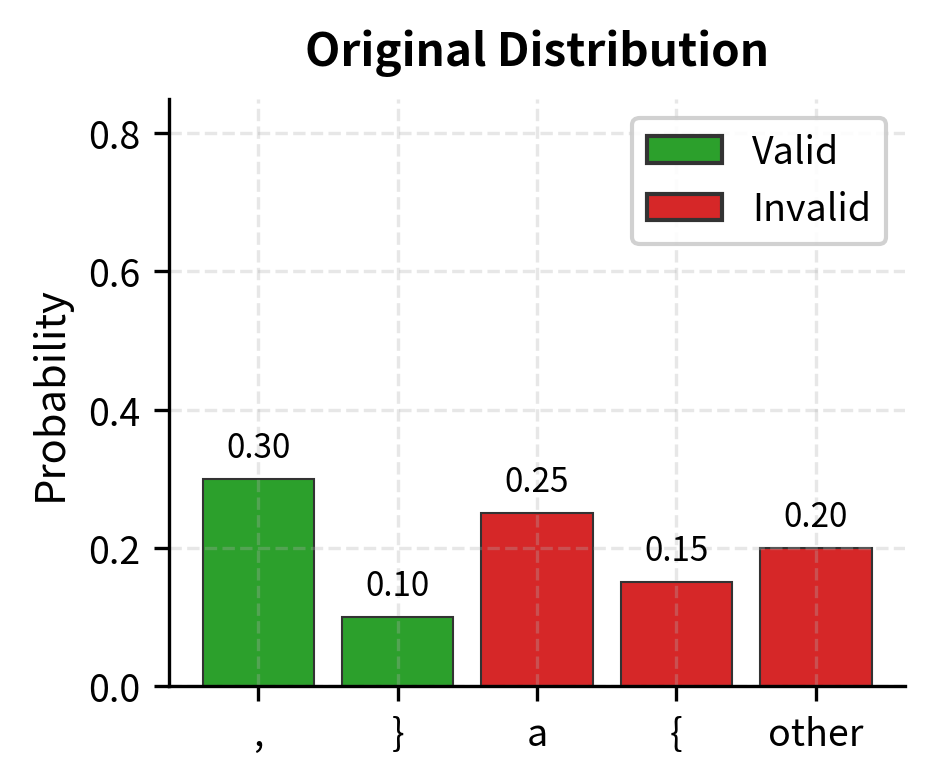

Consider a worked example. Suppose the model produces these probabilities:

| Token | Original | Valid? |

|---|---|---|

, | 0.30 | ✓ |

} | 0.10 | ✓ |

a | 0.25 | ✗ |

{ | 0.15 | ✗ |

| other | 0.20 | ✗ |

The valid tokens (, and }) together have probability mass . The invalid tokens have mass .

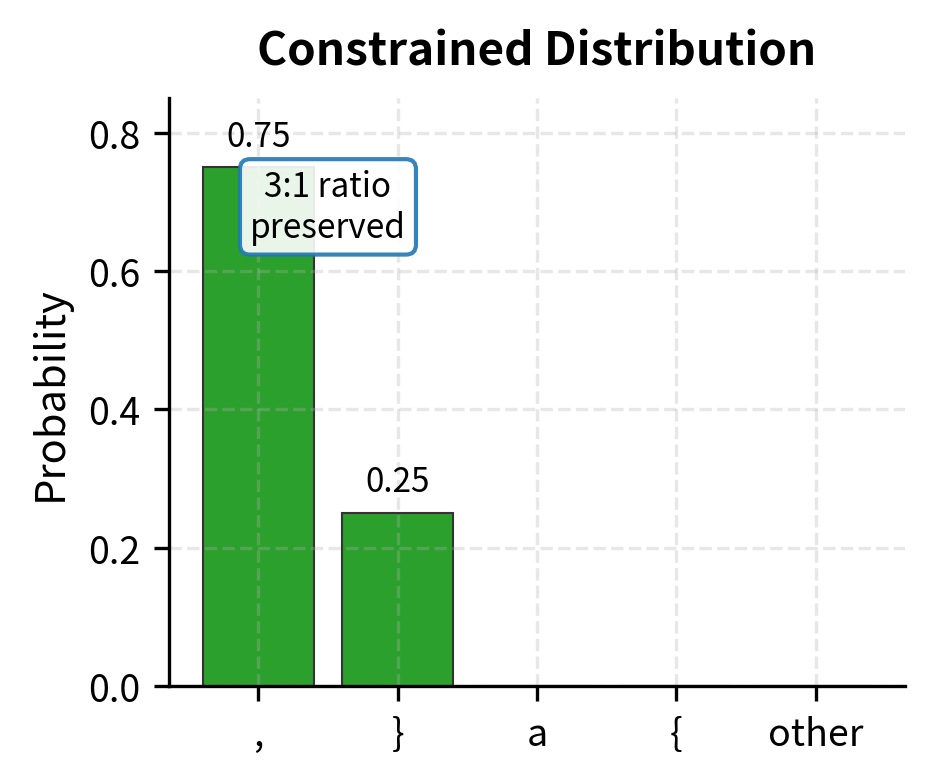

After applying the constrained formula:

- , and so on for all invalid tokens

Notice that the 3:1 ratio between , and } is preserved (0.30:0.10 becomes 0.75:0.25). The model originally preferred comma over closing brace by this ratio, and constrained decoding respects that preference. We've filtered out the impossible options without overriding the model's learned intuitions about likely continuations.

Preserving Model Intelligence

This is the key insight that makes constrained decoding powerful. We're not overriding the model's preferences. We're filtering them. The model brings its understanding of language, context, and likely continuations. The constraint brings the structural requirements. Together, they produce output that is both fluent (because the model guides token selection among valid options) and valid (because invalid options are impossible to select).

If the model assigns probability 0.3 to token A and 0.1 to token B, and both are valid, the constrained distribution preserves this 3:1 ratio. Token A remains three times more likely than token B. We only intervene when the model would choose something structurally invalid.

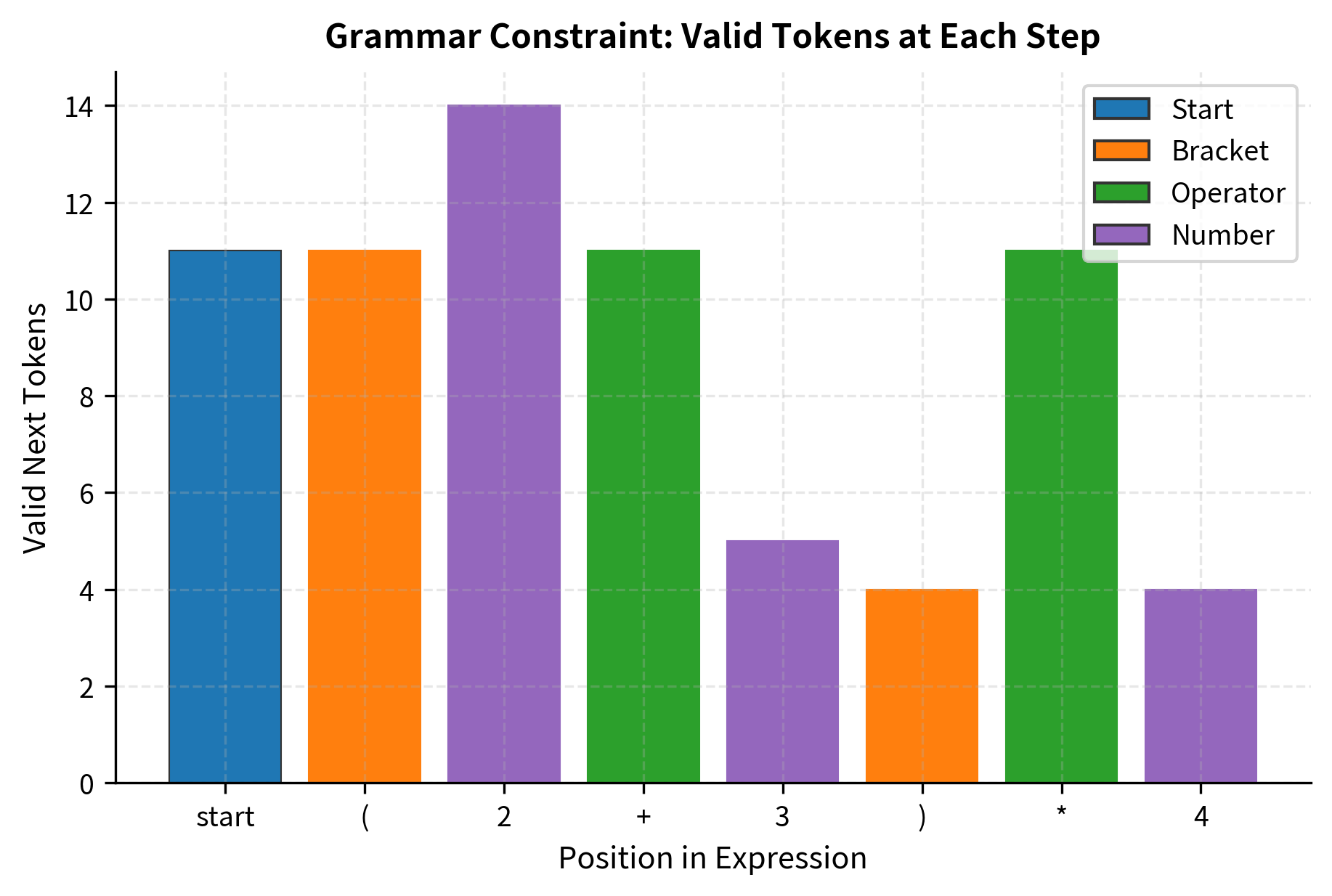

Grammar-Guided Generation

The most powerful form of constrained decoding uses formal grammars to specify valid outputs. A grammar defines the structure of valid strings, and we use it to compute valid tokens at each step.

Context-Free Grammars

Context-free grammars (CFGs) can express the syntax of most structured formats: JSON, XML, SQL, programming languages, and more. A grammar consists of production rules that define how to expand non-terminal symbols into terminals (actual tokens) and other non-terminals.

The parser maintains state as tokens are generated, computing valid continuations at each step. Real grammar-guided generation uses more sophisticated parsing algorithms, but the core principle remains: track the grammar state and filter tokens accordingly.

Implementing Grammar Constraints

For practical grammar-guided generation, we need to map between the language model's tokens (often subwords) and the grammar's terminals. This mapping is non-trivial because a single grammar terminal might span multiple model tokens, and vice versa.

Notice how the sampler never outputs ')' even though the model assigned it the highest logit. The constraint prevents invalid tokens from being selected, while the relative preferences among valid tokens are preserved.

JSON Schema Constraints

JSON is the most common structured format for LLM outputs. Schema-constrained generation ensures the model produces valid JSON that conforms to a specified schema.

From Schema to Grammar

A JSON schema can be converted into a grammar that describes all valid JSON documents matching that schema. This grammar then guides generation token by token.

The Outlines Library

For production use, the Outlines library provides efficient JSON schema constraints. It compiles schemas into finite state machines that run in parallel with generation.

The FSM approach is crucial for performance. Instead of parsing the entire output at each step, we simply look up the current state and get the valid tokens in constant time.

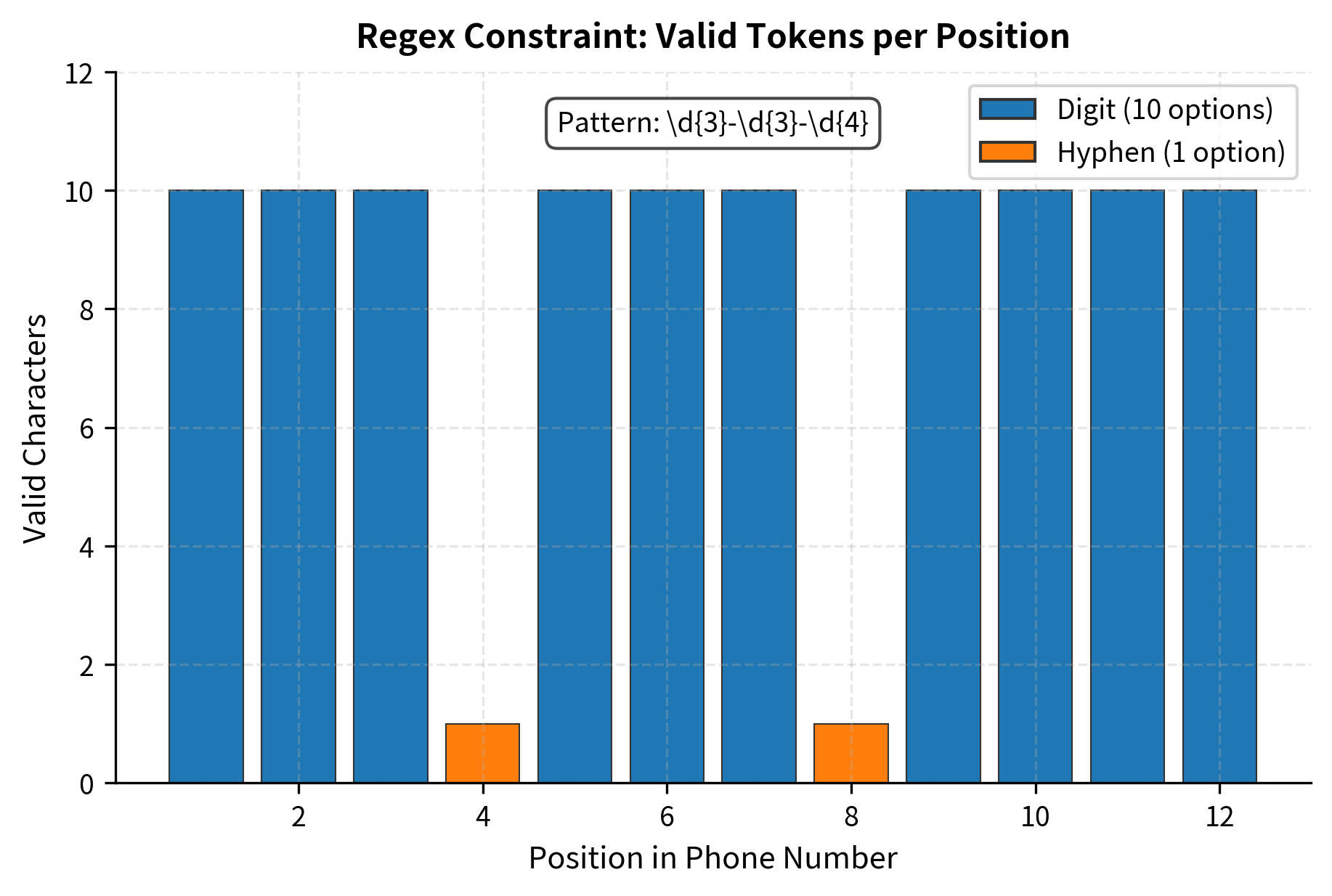

Regex Constraints

Regular expressions provide a flexible way to constrain generation when you need pattern matching without full grammar complexity. Common use cases include:

- Phone numbers:

\d{3}-\d{3}-\d{4} - Email addresses:

[a-zA-Z0-9._%+-]+@[a-zA-Z0-9.-]+\.[a-zA-Z]{2,} - Dates:

\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2} - Custom identifiers:

[A-Z]{2}\d{6}

Regex to DFA Conversion

Regular expressions can be converted to deterministic finite automata (DFAs), which then guide generation exactly like grammar-based FSMs.

The regex constraint ensures that partial outputs always remain on a path toward completing the pattern. Once you've generated "555-", only digits are valid for the next three positions, followed by a mandatory hyphen, then four more digits.

Combining Regex with Semantic Guidance

A powerful technique combines regex constraints with the model's semantic knowledge. The regex ensures format correctness while the model contributes meaningful content.

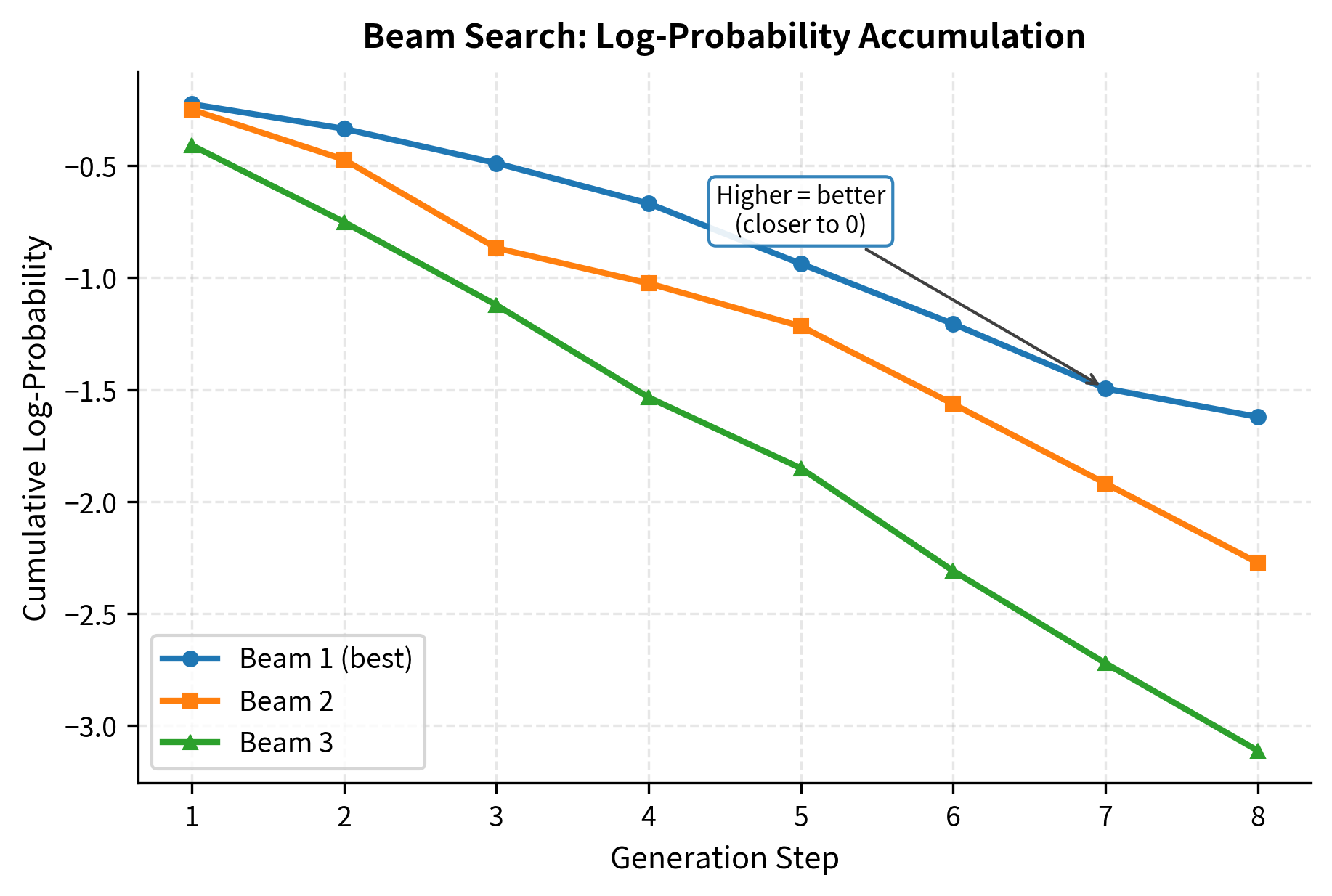

Constrained Beam Search

Beam search maintains multiple candidate sequences to find higher-quality outputs. Adding constraints to beam search requires filtering candidates at each step, keeping only beams that remain on valid paths.

Standard vs Constrained Beam Search

In standard beam search, we expand each beam with the top-k tokens by probability. In constrained beam search, we first filter to valid tokens, then take the top-k among those.

Beam search tracks cumulative log-probabilities rather than raw probabilities. For a sequence of tokens , the log-probability is:

where:

- : the log-probability of the entire sequence

- : the conditional probability of token given all preceding tokens

- : summation over all tokens in the sequence

We use log-probabilities because multiplying many small probabilities quickly leads to numerical underflow. Adding log-probabilities is numerically stable and mathematically equivalent to multiplying the original probabilities.

All three beams contain only characters from the valid set [a-z0-9.], demonstrating that the constraint successfully filtered out any invalid tokens. The top beam "oooooooo" has the highest log-probability because our mock model assigns high weight to vowels. The log-probabilities are negative because we're summing log-probabilities of tokens with probability less than 1.

The constrained beam search explores multiple valid paths simultaneously. Even if the model's top choice at some step is invalid, the beam search can recover by following the next-best valid option. This makes it more robust than greedy constrained decoding.

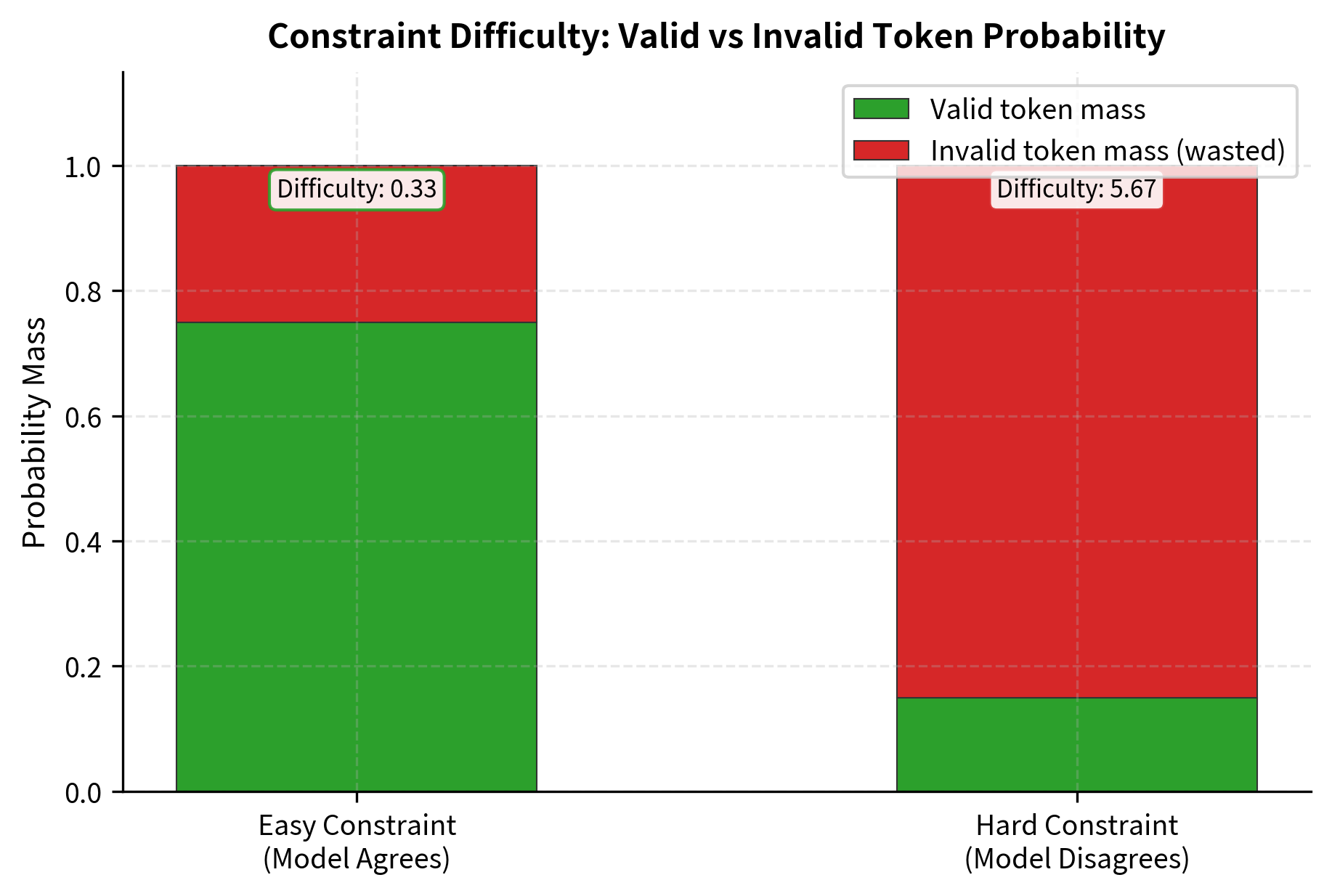

Handling Constraint Conflicts

Sometimes constraints conflict with what the model has learned, leading to low-probability valid tokens. The model might strongly prefer tokens that violate the constraint, leaving only tokens it considers unlikely. This can produce disfluent or unnatural text.

The easy constraint has a difficulty score near 0.33, indicating the model naturally prefers valid tokens. Only 25% of the probability mass goes to invalid options. In contrast, the hard constraint has a difficulty score of 5.67, meaning the model strongly prefers invalid tokens. When 85% of probability mass goes to tokens we must reject, the constrained output may feel forced or unnatural.

When constraint difficulty is high, consider whether the constraint is too restrictive or whether the task requires a model fine-tuned on the target format.

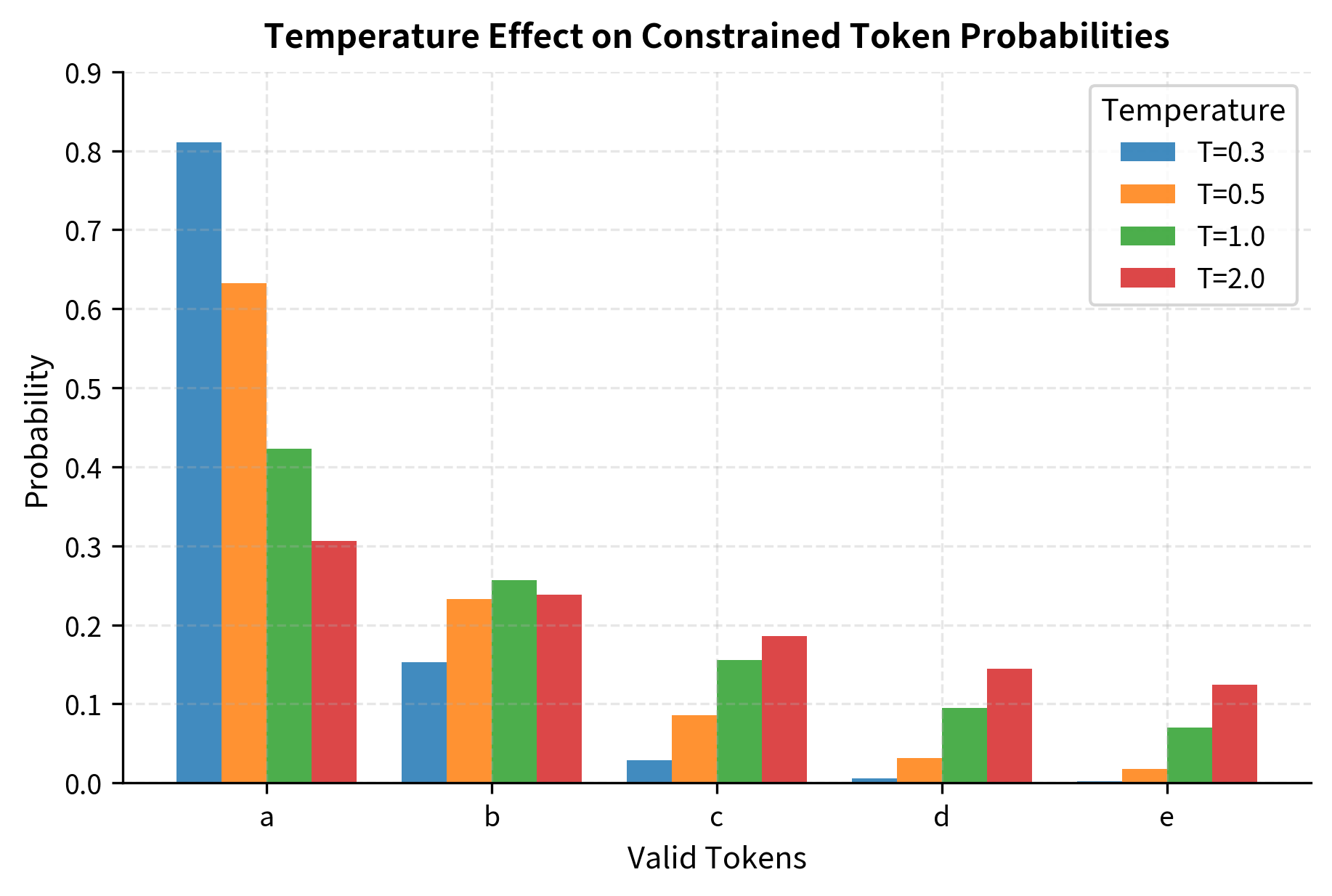

Constrained Sampling Strategies

Beyond masking invalid tokens, we can combine constraints with sampling strategies like temperature, top-k, and nucleus sampling.

Temperature and Constraints

Temperature scaling adjusts the "sharpness" of the distribution. With constraints, we apply temperature before masking to maintain proper probability ratios among valid tokens.

Lower temperatures make the sampler more deterministic within the valid set, while higher temperatures spread probability more evenly across valid options. The constraint always prevents invalid tokens regardless of temperature.

Combining Top-k with Constraints

Top-k sampling and constraints interact in an important way: we should apply constraints first, then take top-k among valid tokens.

A Worked Example: Generating Valid SQL

Let's work through a complete example of constrained decoding for SQL generation. SQL has strict syntax rules that make it an ideal candidate for grammar-guided generation.

Defining the Constraint

We'll generate simple SELECT statements with a constraint that ensures valid syntax.

The SQL constraint leverages schema knowledge to ensure only valid table and column names appear, and it enforces proper keyword ordering.

Full Generation Pipeline

Putting it all together, here's how constrained generation produces a valid SQL query:

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Constrained decoding is powerful but comes with tradeoffs that affect both quality and performance.

Computational Overhead

Computing valid tokens at each generation step adds overhead. For simple regex constraints, this is minimal. For complex grammars or JSON schemas, the constraint checking can become a bottleneck. Production systems address this by precompiling constraints into efficient finite state machines, caching state transitions, and leveraging parallelism. The Outlines library, for instance, compiles JSON schemas into index structures that enable O(1) valid token lookup per step. Without such optimization, naive implementations can increase generation time by 2-5x.

Quality Degradation

When constraints force the model away from its preferred tokens, output quality can suffer. If the model's top-10 tokens are all invalid, it must choose from lower-probability alternatives. This can produce text that is grammatically correct but semantically awkward, like a translation that follows syntax rules but reads unnaturally. Fine-tuning the model on constrained output formats mitigates this problem by aligning the model's preferences with the constraint requirements.

Constraint Expressiveness

Not all requirements can be expressed as grammar or regex constraints. Semantic constraints like "output must be factually accurate" or "response must be polite" cannot be enforced through token masking. Hybrid approaches combine hard syntactic constraints with soft semantic guidance through prompting or reward models. For instance, you might use constrained decoding to ensure valid JSON structure while relying on prompts to guide the content within that structure.

Tokenization Mismatches

Modern language models use subword tokenization, where a single model token might represent multiple characters or partial words. Mapping grammar terminals to model tokens requires careful handling. The token "json" might be a single token in some vocabularies but "js" + "on" in others. Robust implementations must handle these cases, potentially allowing a token if any valid extension of it could eventually satisfy the constraint.

Key Parameters

When implementing constrained decoding, several parameters control the behavior of the system:

-

temperature (float, typically 0.1-2.0): Controls randomness within valid tokens. Lower values make generation more deterministic, always choosing the highest-probability valid token. Higher values spread probability more evenly across valid options. Temperature of 1.0 preserves the model's original distribution.

-

top_k (int, typically 5-50): After filtering to valid tokens, further restricts sampling to the k highest-probability options. Reduces variance in generation by excluding low-probability valid tokens.

-

beam_width (int, typically 3-10): For constrained beam search, determines how many candidate sequences to maintain. Larger widths explore more paths but increase computation linearly.

-

max_length (int): Maximum number of tokens to generate. Prevents infinite loops when constraints allow arbitrarily long valid sequences.

-

constraint_type: The type of constraint to apply. Options include grammar-based (context-free grammars), schema-based (JSON schemas), regex-based (regular expressions), or custom constraint functions.

For production use with JSON output, libraries like Outlines handle these parameters automatically. For custom constraints, start with temperature=1.0 and no top_k filtering to preserve the model's preferences, then tune based on output quality.

Summary

Constrained decoding transforms language model generation from probabilistic text production into structured output generation. The key concepts covered in this chapter include:

- Token masking forms the foundation: at each step, we zero out probabilities for tokens that would violate constraints, then sample from the remaining valid tokens

- Grammar-guided generation uses formal grammars (typically context-free grammars compiled to finite state machines) to specify valid output structures and compute valid tokens efficiently

- JSON schema constraints convert schemas into grammars that enforce both valid JSON syntax and adherence to the specified schema structure

- Regex constraints provide a lighter-weight alternative for pattern matching, converted to DFAs for efficient constraint checking

- Constrained beam search extends beam search to maintain multiple valid hypotheses, enabling recovery from locally suboptimal choices

- Combining with sampling strategies allows constraints to work alongside temperature, top-k, and nucleus sampling for controlled randomness within valid outputs

The technique has become essential for building reliable AI systems that must produce machine-readable output. When you need a language model to return valid JSON, generate syntactically correct code, or produce output matching any formal specification, constrained decoding provides the guarantee that pure prompting cannot.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about constrained decoding and structured output generation.

Comments