Learn how repetition penalty, frequency penalty, presence penalty, and n-gram blocking prevent language models from getting stuck in repetitive loops during text generation.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Repetition Penalties

Language models have a peculiar tendency to get stuck in loops. Ask GPT to write a story, and without intervention, you might get output like "The cat sat on the mat. The cat sat on the mat. The cat sat on the mat..." This repetitive behavior emerges from a fundamental property of autoregressive generation: at each step, the model selects tokens that maximize likelihood given the context, and if a pattern worked once, the same pattern often has high probability again.

Repetition is not always undesirable. Certain phrases naturally repeat in language: "again and again", "more and more", or the rhythmic repetition in poetry and song lyrics. But uncontrolled repetition signals a failure mode where the model has collapsed into a degenerate loop, producing text that no human would write. This chapter explores techniques to prevent such loops while preserving natural language patterns.

We'll examine three approaches that modify the probability distribution during generation. Repetition penalty scales down the logits of previously used tokens. Frequency penalty applies increasingly strong penalties based on how many times each token has appeared. Presence penalty applies a flat penalty to any token that has appeared at all. We'll also explore n-gram blocking, a deterministic approach that prevents exact phrase repetition. Each technique offers different trade-offs between preventing loops and preserving natural repetition.

Why Models Repeat Themselves

Before diving into solutions, let's understand why repetition happens. The answer lies in how autoregressive models generate text and how they're trained.

During training, language models learn to predict the next token given all previous tokens. They're optimized to assign high probability to tokens that frequently follow specific contexts in the training data. When a particular phrase or structure appears often in training text, the model learns to give it high probability in similar contexts.

The problem manifests during generation. Suppose the model generates "The results show that" and then produces "the model performs well." Now "The results show that the model performs well" becomes part of the context. If the training data contained similar patterns of presenting multiple results, the phrase "The results show that" might again have high probability, leading to another similar sentence. Each repetition reinforces the pattern in the context, making further repetition even more likely.

The output may contain repetitive phrases or sentence structures. While sampling strategies like temperature and nucleus sampling add randomness, they don't specifically target repetition. A token that appeared recently still has the same probability as before, so the model can easily select it again.

The Feedback Loop

Repetition often starts subtly and escalates. The model might repeat a word, then a phrase, then entire sentences. This acceleration happens because each repetition adds more of the same pattern to the context, which the model uses to predict the next token. The context becomes increasingly dominated by the repeated content, making continuation of that content more and more likely.

Consider a model generating a list. After producing "First, we need to consider..." it might generate "Second, we need to consider..." and then "Third, we need to consider...". So far, this is reasonable parallel structure. But without intervention, the model might continue with "Fourth, we need to consider..." long after the list should have ended, trapped in a pattern that keeps reinforcing itself.

The Repetition Penalty

The most direct approach to preventing repetition modifies the logits for tokens that have already appeared in the generated sequence. The repetition penalty, introduced by Keskar et al. (2019) in the CTRL paper, divides the logits of previously seen tokens by a penalty factor, making them less likely to be selected.

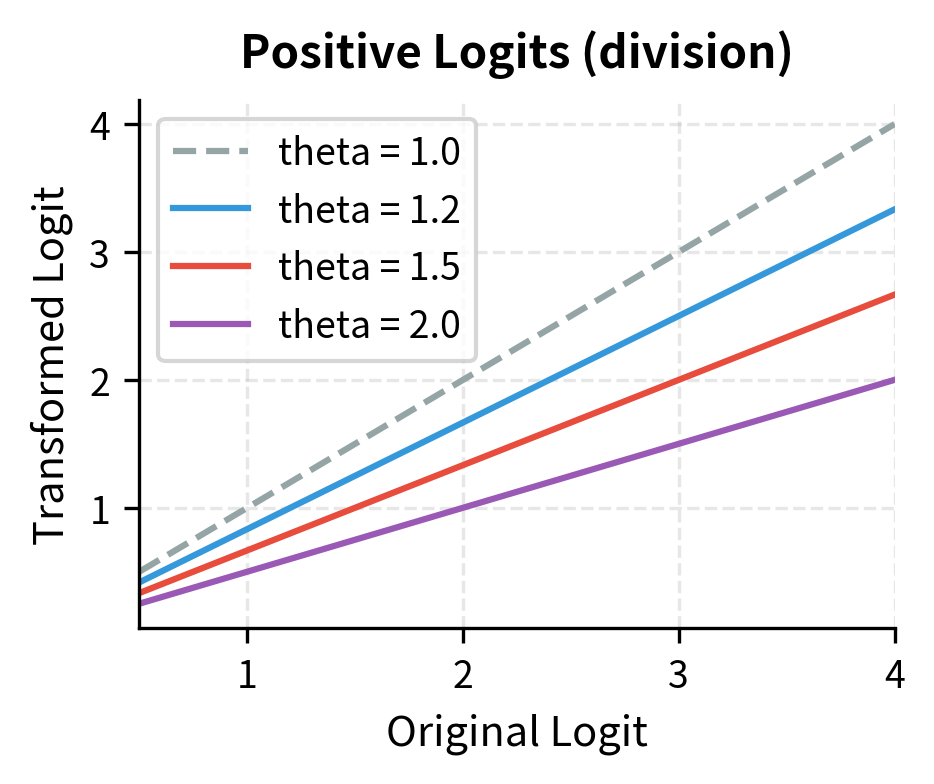

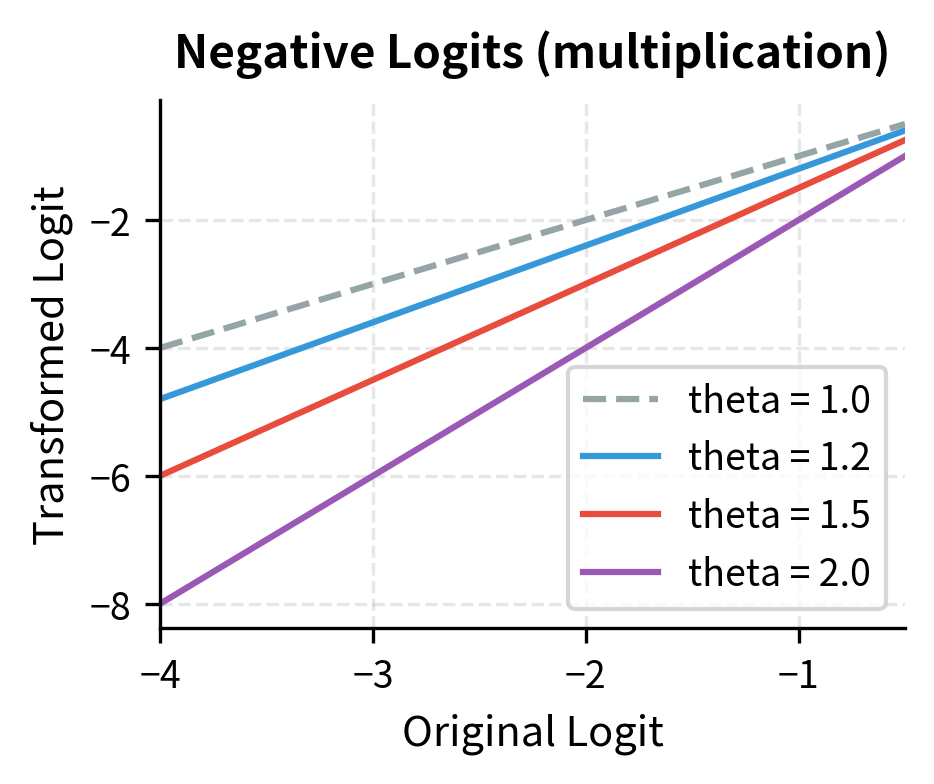

The repetition penalty modifies logits for tokens that appear in the existing context. For each token that has already been generated, its logit is divided by the penalty factor if positive, or multiplied by if negative. This reduces the probability of repeating tokens without eliminating them entirely.

Mathematical Formulation

To understand how repetition penalty works, we need to trace the path from model output to token selection. When a language model predicts the next token, it doesn't output probabilities directly. Instead, it produces logits: raw, unnormalized scores for each token in the vocabulary. These logits then pass through the softmax function to become probabilities, and finally, we sample from that probability distribution.

This pipeline gives us a natural intervention point. If we want to reduce the probability of certain tokens, we can modify their logits before softmax. The question is: how should we modify them?

The Core Insight

Our goal is straightforward: make previously used tokens less likely to appear again. Since softmax converts logits to probabilities, reducing a logit reduces its corresponding probability. But there's a subtlety. Logits can be positive or negative, and the operation that reduces a positive number (division) actually increases a negative number (makes it closer to zero). We need an operation that pushes logits in the "less likely" direction regardless of their sign.

The solution is a piecewise function that applies different operations based on the sign of the logit. Let be the logit for token and let be the set of tokens that have already appeared in the generated sequence. The repetition penalty modifies logits as follows:

where:

- : the original logit for token , the raw score from the model before softmax

- : the modified logit after applying the penalty

- : the repetition penalty factor, typically in the range

- : the set of token indices that have appeared in the context

- : notation meaning "token is a member of set " (i.e., token has appeared before)

The formula reads: for each token, check if it has appeared before. If it has and its logit is positive, divide by the penalty factor. If it has and its logit is zero or negative, multiply by the penalty factor. If it hasn't appeared, leave it unchanged.

Why the Asymmetric Treatment?

This asymmetry might seem arbitrary, but it follows directly from how softmax works. Recall that softmax converts a logit to a probability:

The probability depends on , the exponential of the logit. The exponential function is strictly increasing: larger inputs produce larger outputs. So to reduce , we must reduce .

For a positive logit like , dividing by gives . Since , we've reduced the logit and thus reduced the probability. Division works as intended.

For a negative logit like , the same division gives . But (it's closer to zero), so we've actually increased the logit and the probability. Division fails here.

The fix is multiplication. Multiplying by gives . Since , we've pushed the logit further negative, reducing the probability. Both operations, division for positive logits and multiplication for negative ones, consistently reduce probability.

The Neutral Case

When , the penalty has no effect. Dividing by 1 or multiplying by 1 leaves any number unchanged. This gives us a natural "off switch" for the penalty and a baseline for comparison. As increases above 1.0, the penalty strengthens, pushing repeated tokens further toward improbability.

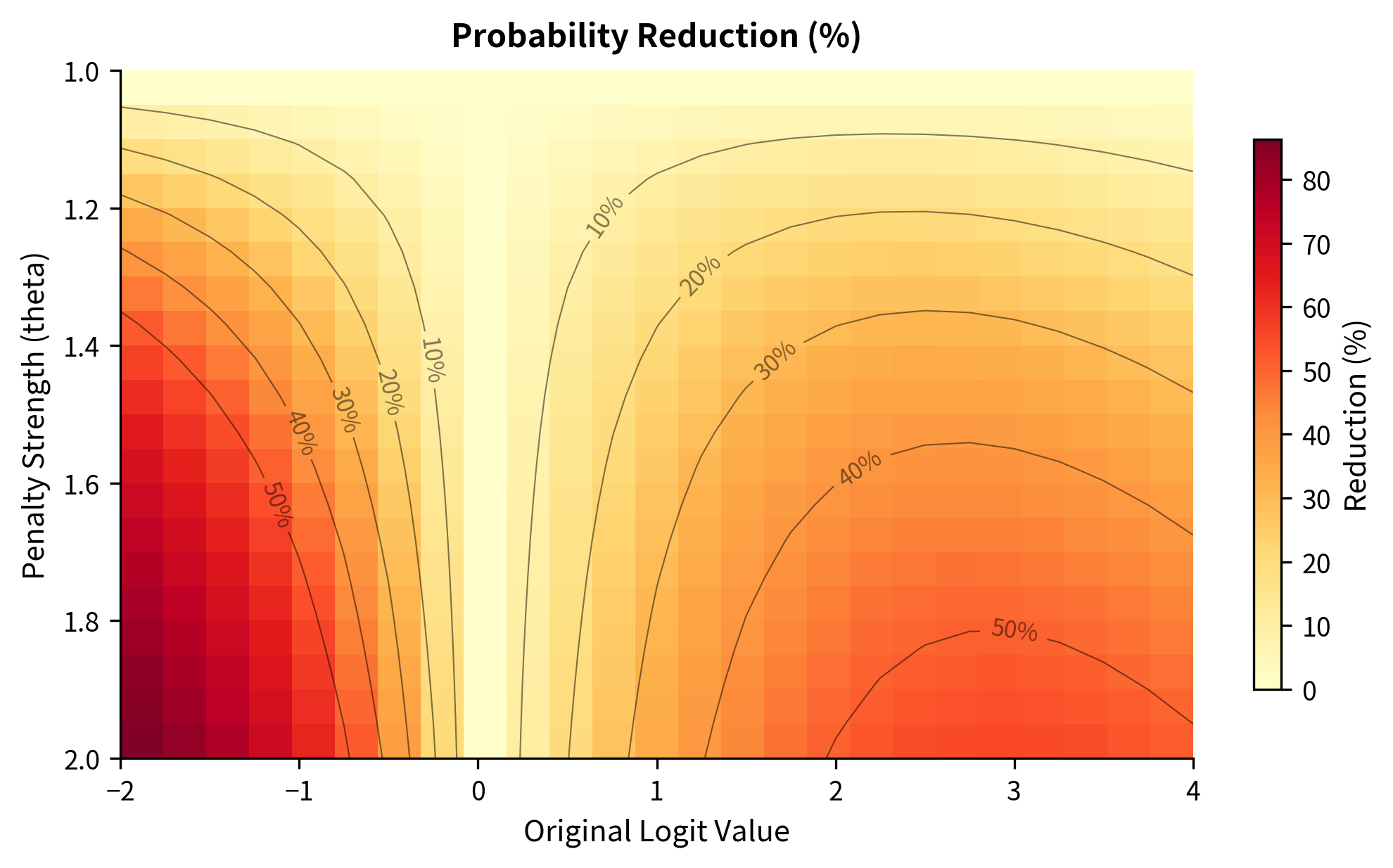

The visualization shows the key insight: for positive logits, division pulls values toward zero (reducing probability), while for negative logits, multiplication pushes values further negative (also reducing probability). Both transformations achieve the same goal through different arithmetic operations.

Implementation

Let's implement the repetition penalty from scratch to see exactly how it works:

The function iterates through each token that has appeared in the context and applies the appropriate modification based on the sign of its logit. This is conceptually simple but reveals an important property: the penalty treats all repeated tokens equally, whether they appeared once or a hundred times.

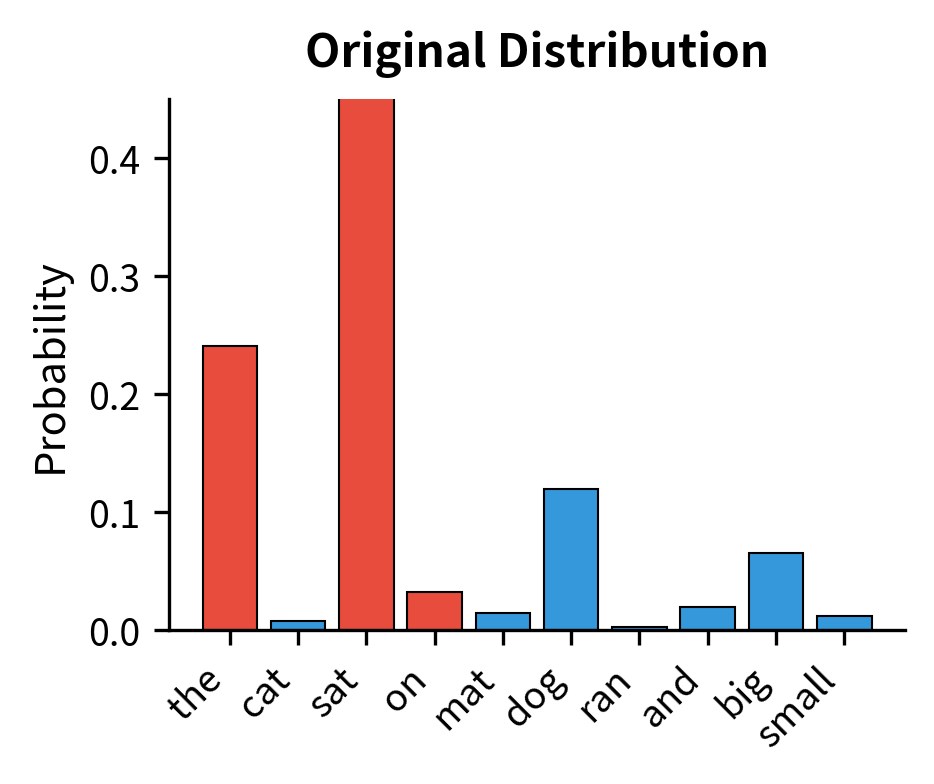

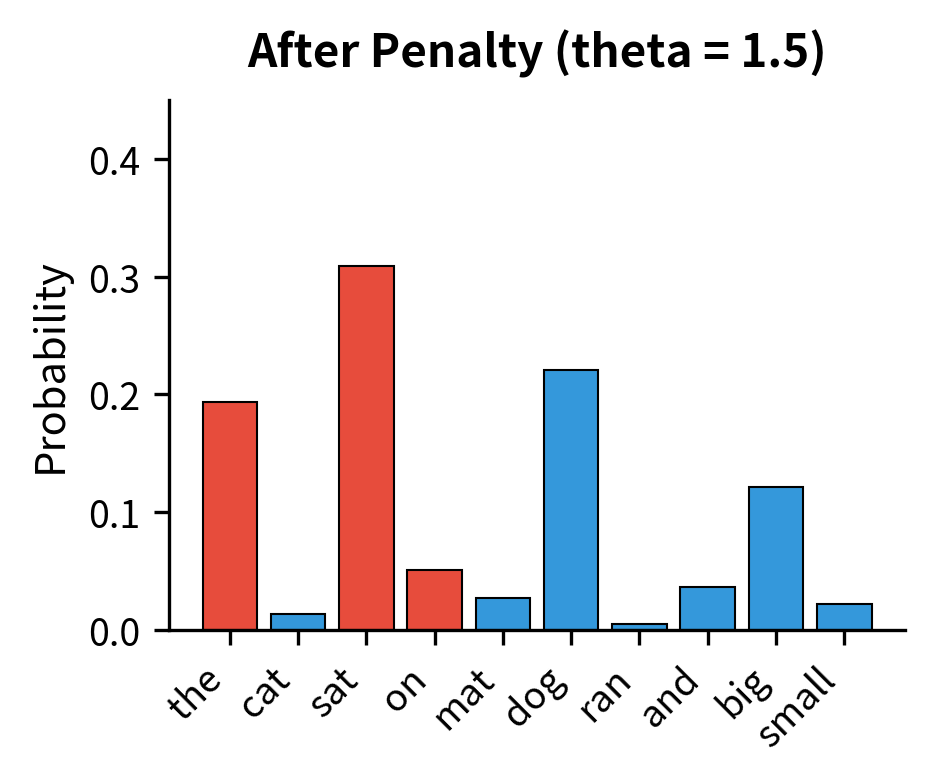

The table shows how the repetition penalty redistributes probability mass. Tokens that appeared in the context (marked with *) have their probabilities reduced, while tokens that haven't appeared receive proportionally higher probabilities. Notice that "sat" (token 2), which had the highest original logit, is no longer the most likely token after applying the penalty.

Visualizing the Effect

Choosing the Penalty Value

The repetition penalty parameter requires careful tuning. Too low, and repetition persists. Too high, and the model avoids necessary repetition, producing awkward text that never uses "the" or "a" more than once.

Common values and their effects:

- : No penalty applied. Baseline behavior with full repetition potential.

- to : Light penalty. Gently discourages repetition while allowing natural patterns. Good starting point for most applications.

- to : Moderate penalty. Noticeably reduces repetition. May affect fluency for texts requiring repeated terms (technical writing, legal documents).

- : Strong penalty. Significantly suppresses any repeated token. Can produce stilted or unnatural text, especially for longer outputs.

As the penalty increases, you'll notice the text becomes more varied in vocabulary but may also become less coherent. The model is forced to find alternative words even when repetition would be natural.

The heatmap reveals an important pattern: the probability reduction depends on both the penalty strength and the token's original standing. Tokens with moderate positive logits (around 1-3) experience the largest percentage reductions because they start with meaningful probability that can be substantially reduced. Very high logits still dominate even after penalty, while very low logits have little probability to lose.

Frequency Penalty

While repetition penalty treats all repeated tokens identically, frequency penalty scales with occurrence count. A token used once receives a small penalty; a token used ten times receives ten times that penalty. This graduated approach allows some repetition while strongly discouraging excessive use of any single token.

Frequency penalty subtracts a value from each token's logit proportional to how many times that token has appeared in the generated text. The formula is , where is the penalty strength and is the number of times token has been generated.

Mathematical Formulation

Repetition penalty has a limitation: it treats a token that appeared once the same as one that appeared fifty times. Both receive the same penalty. But intuitively, we might want to allow occasional repetition (the word "the" naturally appears multiple times in most texts) while strongly discouraging tokens that have become overused. This calls for a penalty that accumulates with each occurrence.

From Binary to Graduated Penalties

Frequency penalty introduces a simple but powerful shift: instead of asking "has this token appeared?", we ask "how many times has this token appeared?" The penalty then scales proportionally with the answer.

The mechanism is additive rather than multiplicative. For each occurrence of a token, we subtract a fixed amount from its logit. Let denote the number of times token has appeared in the generated sequence. The frequency penalty modifies logits as:

where:

- : the original logit for token

- : the modified logit after applying the penalty

- : the frequency penalty coefficient, typically in the range , controlling how strongly each occurrence is penalized

- : the count of token in the generated sequence (0 if the token has not appeared)

The formula subtracts once for each time the token has appeared. If a token appeared three times and , we subtract from its logit.

Why Additive Works

Unlike repetition penalty, frequency penalty doesn't need to handle positive and negative logits differently. Subtraction always reduces a number, regardless of its sign. Subtracting from a positive logit makes it smaller (or even negative). Subtracting from a negative logit makes it more negative. Both operations reduce the logit and thus reduce the probability after softmax.

This simplicity is a feature. The formula is easy to implement, easy to understand, and produces predictable behavior: each occurrence adds the same "cost" to using that token again.

Linear Scaling in Action

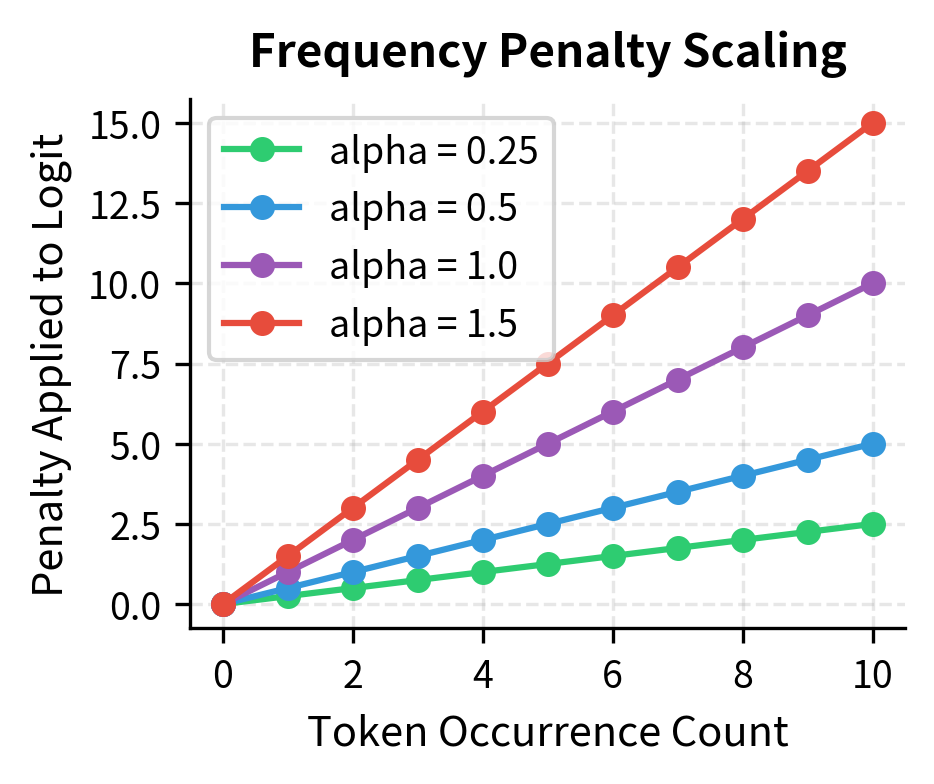

The linearity of frequency penalty creates a distinctive pattern. Early occurrences of a token receive mild penalties, allowing natural repetition of common words. But as a token accumulates, the penalty grows relentlessly. Consider :

| Occurrences | Penalty Applied |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 1.0 |

| 5 | 2.5 |

| 10 | 5.0 |

By the tenth occurrence, the token's logit has been reduced by 5.0, a substantial penalty that makes it far less competitive against tokens that haven't been overused. This graduated pressure naturally prevents any single token from dominating the output without harsh early constraints.

Implementation

Let's see how frequency penalty differs from repetition penalty:

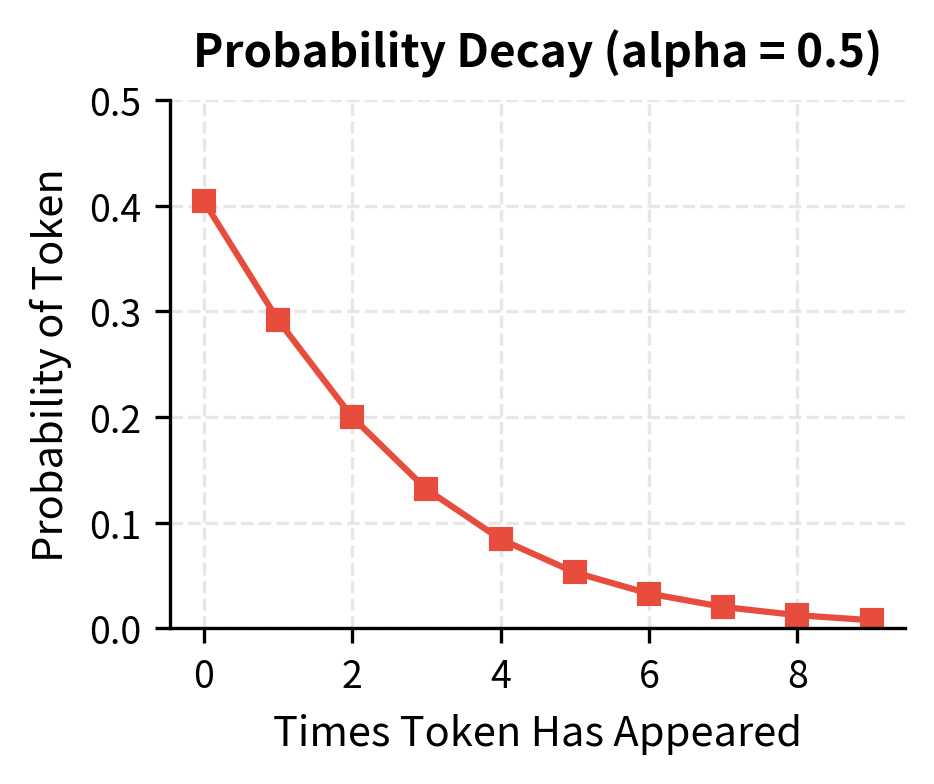

The key difference is apparent: tokens with higher counts receive proportionally stronger penalties. "The", which appeared 5 times, has its logit reduced by 2.5 (5 × 0.5), while "data", which appeared once, only loses 0.5 from its logit. This graduated penalty is particularly effective for suppressing overused words while allowing reasonable repetition of less common terms.

Visualizing Frequency Penalty

Presence Penalty

Presence penalty takes an even simpler approach: penalize any token that has appeared, regardless of how many times. This binary penalty treats "appeared once" and "appeared twenty times" identically.

Presence penalty applies a fixed penalty to the logit of any token that has appeared in the generated text, regardless of frequency. The formula is , where is the penalty strength and is an indicator that equals 1 if token has appeared and 0 otherwise.

Mathematical Formulation

We've now seen two approaches: repetition penalty treats all repeated tokens equally (ignoring count), while frequency penalty scales with count. Presence penalty takes the opposite extreme from frequency penalty: it also ignores count, but uses the simpler additive mechanism.

The Binary Question

Presence penalty asks the simplest possible question about each token: "Have you appeared before, yes or no?" If yes, apply a fixed penalty. If no, leave the logit unchanged. The number of previous occurrences is irrelevant.

To express this mathematically, we use an indicator function, a standard notation for encoding yes/no conditions as 1/0 values:

where:

- : the original logit for token

- : the modified logit after applying the penalty

- : the presence penalty coefficient, controlling how strongly any prior appearance is penalized

- : the indicator function, which equals 1 if token has appeared (is in set ), and 0 otherwise

- : the set of tokens that have appeared in the generated sequence

Reading the Indicator Function

The notation might look intimidating, but it simply acts like a switch. The condition inside the brackets, "" (token is in set ), is evaluated as true or false. The indicator function converts this to a number:

- If the condition is true (token has appeared):

- If the condition is false (token has not appeared):

Substituting back into the formula:

- For a token that has appeared:

- For a token that hasn't appeared:

The indicator function elegantly handles both cases in a single equation.

Presence vs. Frequency: A Comparison

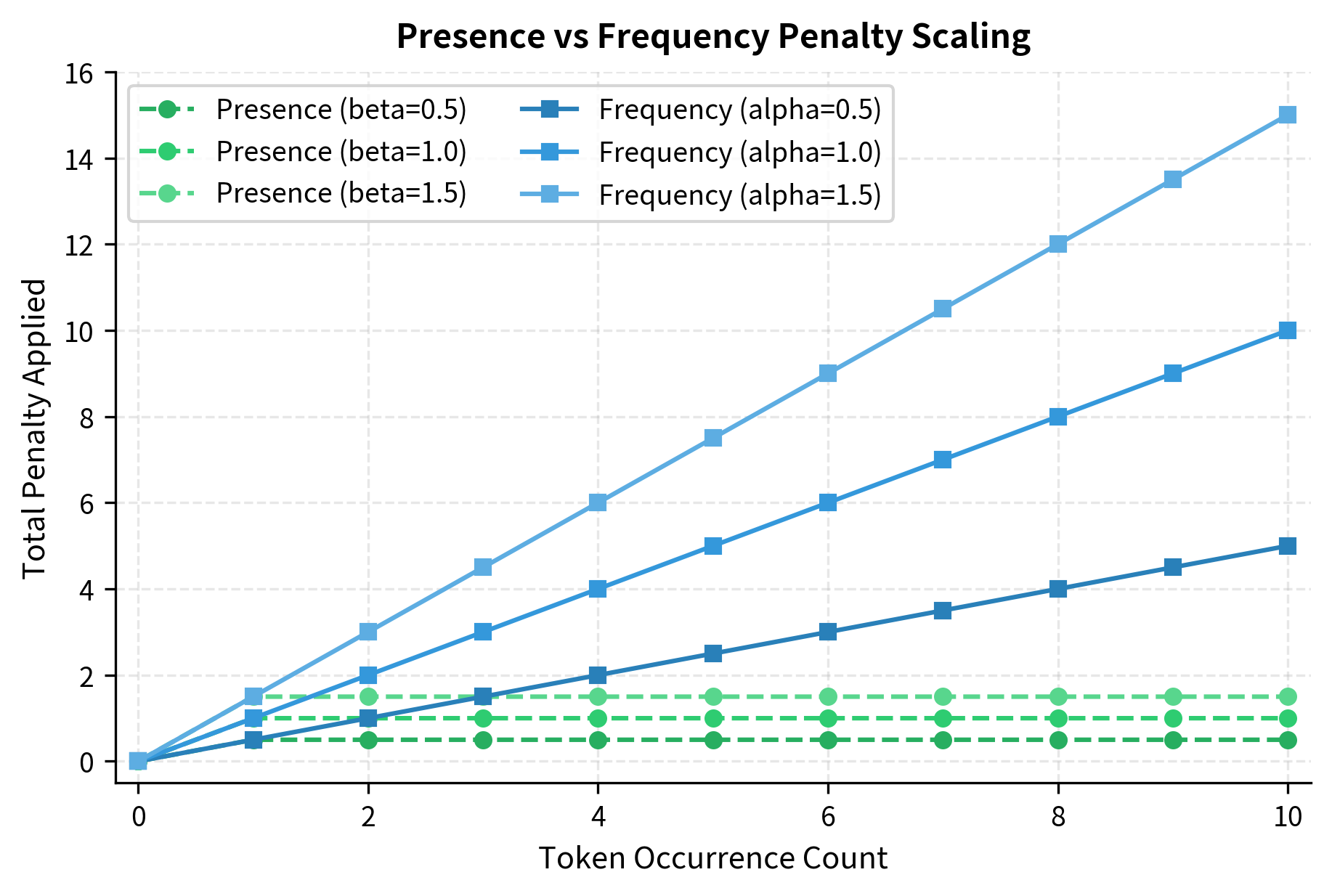

The contrast with frequency penalty is instructive. Frequency penalty applies for each occurrence, so a token appearing 10 times receives 10 times the penalty of one appearing once. Presence penalty applies exactly once regardless of occurrence count. Whether a token appeared 1 time or 100 times, it receives the same penalty .

This makes presence penalty particularly effective for encouraging vocabulary diversity. Once a word has been used, it faces a fixed "tax" on appearing again. The model is pushed to explore alternatives, to find synonyms, to vary its phrasing. It's a blunt instrument compared to frequency penalty's graduated pressure, but for tasks like brainstorming or generating diverse lists, that bluntness can be exactly what's needed.

The contrast is stark. Presence penalty (dashed lines) jumps to its full value after the first occurrence and stays flat. Frequency penalty (solid lines) starts at zero and grows steadily. For tokens that appear many times, frequency penalty eventually dominates; for tokens that appear just once or twice, presence penalty applies stronger immediate pressure.

Implementation

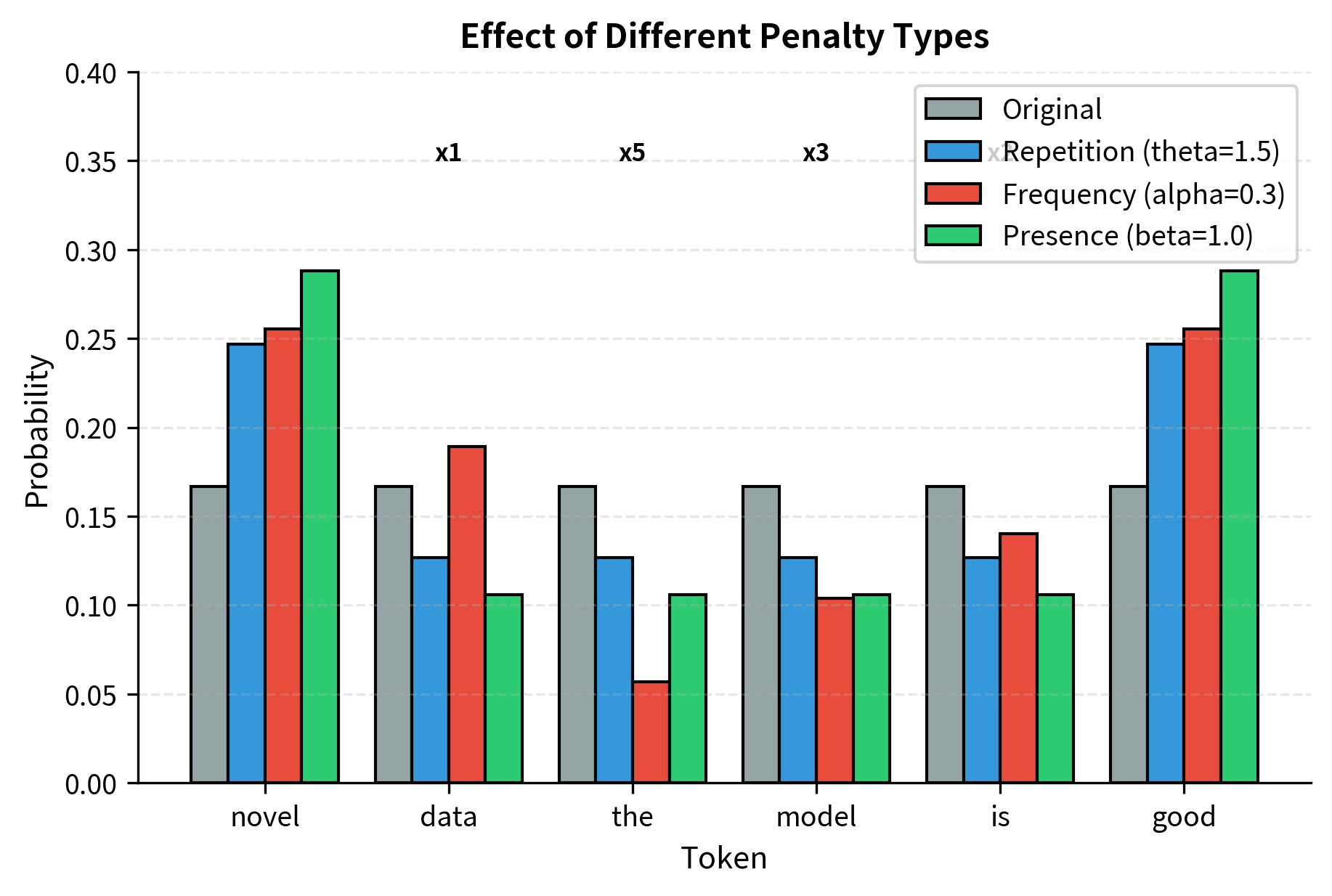

Comparing All Three Penalties

Let's see how the three penalties differ when applied to the same scenario:

The visualization reveals each penalty's character:

- Repetition penalty (blue) uniformly reduces all appeared tokens, regardless of count

- Frequency penalty (red) creates graduated reductions: "the" (×5) drops dramatically while "data" (×1) drops minimally

- Presence penalty (green) applies equal reduction to all appeared tokens, similar to repetition penalty but using additive rather than multiplicative adjustment

N-gram Blocking

The penalties we've explored so far are probabilistic: they reduce the likelihood of repetition without preventing it entirely. N-gram blocking takes a deterministic approach by absolutely forbidding the repetition of specific token sequences.

N-gram blocking prevents the model from generating any n-gram (sequence of n consecutive tokens) that has already appeared in the generated text. When the model would complete a forbidden n-gram, that token's probability is set to zero, forcing selection of a different continuation.

How N-gram Blocking Works

The penalties we've explored, repetition, frequency, and presence, all work by adjusting probabilities. They make repetition less likely but don't prevent it entirely. Sometimes a token's original probability is so high that even after penalization, it remains the most likely choice. For applications where exact repetition would be clearly wrong (legal documents, safety-critical outputs), we need a stronger guarantee.

N-gram blocking provides that guarantee through a fundamentally different mechanism: instead of adjusting probabilities, it eliminates certain tokens from consideration entirely by setting their probability to zero.

What Is an N-gram?

An n-gram is simply a contiguous sequence of n tokens. The terminology comes from computational linguistics:

- A bigram (2-gram) is a sequence of 2 tokens, like ["the", "cat"]

- A trigram (3-gram) is a sequence of 3 tokens, like ["sat", "on", "the"]

- A 4-gram is a sequence of 4 tokens, like ["the", "quick", "brown", "fox"]

N-gram blocking maintains a record of all n-grams that have appeared in the generated text. Before each token is sampled, the algorithm checks: "If I generate this token, will it complete an n-gram that already exists?" If so, that token is forbidden.

The Blocking Mechanism

Consider 3-gram blocking with the sequence "machine learning is powerful. Machine learning is". The current context ends with "Machine learning". If the model generates "is", it would create the trigram ["Machine", "learning", "is"], which already appeared earlier. N-gram blocking detects this and sets the probability of "is" to zero, forcing the model to choose a different continuation.

This is absolute prevention, not probabilistic discouragement. No matter how strongly the model wants to generate "is", it cannot. The token is masked out before sampling occurs.

Let's trace through an example:

The output shows all trigrams extracted from the sentence. Since the context ends with "quick brown" and the trigram ["quick", "brown", "fox"] already exists, generating "fox" next would create an exact repetition. N-gram blocking identifies this and adds "fox" to the banned token list, forcing the model to choose a different continuation.

Implementation in Generation

With 2-gram blocking, the text avoids repeating any two consecutive tokens, which can make the output feel choppy since common phrases like "of the" can only appear once. With 3-gram blocking, the constraint relaxes slightly, allowing more natural flow while still preventing obvious repetition. At 4-gram blocking, only longer repeated phrases are blocked, preserving most natural language patterns while catching more egregious loops.

Trade-offs of N-gram Blocking

N-gram blocking guarantees no exact phrase repetition but has notable limitations:

- Rigidity: It cannot distinguish between undesirable repetition and natural language patterns. Phrases like "on the other hand" might be blocked after first use, even when appropriate.

- Local focus: It only prevents exact matches. "The cat sat" and "A cat sat" are different trigrams, so both could appear despite semantic similarity.

- Brittleness: The blocking can force awkward workarounds when the model genuinely needs to repeat a phrase.

Smaller n values (2 or 3) are more restrictive but may hurt fluency. Larger values (4 or 5) allow more natural repetition while still preventing obvious loops.

Combining Penalties with Sampling Strategies

In practice, repetition penalties work alongside temperature, top-k, and nucleus sampling. The typical processing order is:

- Get raw logits from the model

- Apply repetition/frequency/presence penalties to adjust logit values

- Apply temperature scaling to control distribution sharpness

- Apply top-k or nucleus truncation to limit candidates

- Sample from the resulting distribution

Comparing the outputs reveals how each penalty type shapes generation. Without penalties, the model may fall into repetitive patterns. Repetition penalty alone provides uniform discouragement of repeated tokens. Frequency penalty creates graduated pressure that builds as tokens accumulate, while presence penalty encourages the model to continuously introduce new vocabulary. The combined approach balances these effects, often producing the most natural-sounding output by gently discouraging repetition without forcing unnatural word choices.

When to Use Each Penalty

The choice between penalty types depends on your generation task:

Repetition Penalty works well as a general-purpose solution. It's the most widely implemented (available in Hugging Face's generate() method) and handles most cases adequately. Use it when you want a simple, effective baseline for reducing repetition.

Frequency Penalty excels when you want to allow some repetition while preventing excessive use. It's particularly useful for:

- Long-form content where occasional word repetition is acceptable but word overuse is not

- Creative writing where you want natural variation without harsh constraints

- Technical writing where certain terms must repeat but shouldn't dominate

Presence Penalty promotes vocabulary diversity and topic breadth. Consider it for:

- Brainstorming and idea generation where you want many distinct concepts

- Summarization where you want to cover multiple points without redundancy

- Conversational agents that should avoid fixating on specific words

N-gram Blocking provides guaranteed protection against exact repetition. Use it when:

- Exact phrase repetition would be clearly wrong (e.g., safety-critical applications)

- You need deterministic behavior rather than probabilistic reduction

- Other penalties aren't sufficiently preventing loops

For many applications, combining moderate repetition penalty (-) with nucleus sampling provides a good balance between preventing loops and maintaining fluent output.

Key Parameters

When implementing repetition penalties in generation, these parameters control behavior:

-

repetition_penalty(float, typically 1.0-2.0): Multiplicative penalty applied to logits of repeated tokens. A value of 1.0 applies no penalty. Values around 1.1-1.3 provide gentle repetition reduction. Values above 1.5 strongly discourage any repetition. -

frequency_penalty(float, typically 0-2.0): Additive penalty proportional to token occurrence count. Higher values increasingly penalize frequently used tokens. OpenAI's API uses this parameter with typical values of 0-1.0. -

presence_penalty(float, typically 0-2.0): Flat additive penalty for tokens that have appeared at all. Encourages vocabulary diversity. Also used in OpenAI's API with typical values of 0-1.0. -

no_repeat_ngram_size(int): Size of n-grams to block from repeating. In Hugging Face'sgenerate(), setting this to 2 prevents any bigram repetition, 3 prevents trigram repetition, etc. Set to 0 to disable. -

encoder_no_repeat_ngram_size(int): For encoder-decoder models, prevents generating n-grams that appear in the encoder input. Useful for abstractive summarization to avoid copying source phrases.

Summary

Repetition is a common failure mode in language model generation, emerging from the autoregressive process where patterns reinforce themselves through context accumulation. Several techniques address this problem by modifying token probabilities based on prior usage.

Key takeaways:

-

Repetition penalty divides logits of previously generated tokens by a penalty factor, uniformly reducing their probability regardless of occurrence count. Simple and effective for general use.

-

Frequency penalty subtracts from logits proportionally to occurrence count, creating graduated penalties that scale with overuse. Allows natural repetition while strongly penalizing excessive use.

-

Presence penalty applies a flat reduction to any token that has appeared, promoting vocabulary diversity. Effective for brainstorming and ensuring broad coverage.

-

N-gram blocking deterministically prevents exact phrase repetition by masking tokens that would complete a previously seen n-gram. Provides guaranteed protection but can reduce fluency.

-

Order matters: Apply penalties before temperature and sampling truncation. The modified logits then flow through the standard sampling pipeline.

-

Context window: Consider whether penalties apply to the full context (including prompt) or only generated tokens. Most implementations penalize tokens anywhere in the sequence, which can affect prompt-relevant words.

The optimal configuration depends heavily on your use case. Start with a moderate repetition penalty (-), observe the output quality, and adjust based on whether you see too much repetition or unnaturally varied vocabulary. For production systems, A/B testing different configurations against human evaluations provides the most reliable guidance.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about repetition penalties in language model generation.

Comments