Learn how ALBERT reduces BERT's size by 18x using factorized embeddings and cross-layer parameter sharing while maintaining competitive performance.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

ALBERT

BERT's success came at a cost: it was enormous. BERT-Large packed 340 million parameters into a model that required significant GPU memory just to fine-tune. Scaling language models further seemed to require proportionally more parameters, memory, and compute. But does it have to be this way?

ALBERT (A Lite BERT) challenged this assumption. Published by Google Research in 2019, ALBERT introduced two parameter-reduction techniques that slashed model size by up to 18x while maintaining competitive performance. The key insight was that much of BERT's parameter budget was redundant. By factorizing the embedding matrix and sharing parameters across layers, ALBERT demonstrated that smaller models could learn equally rich representations.

This chapter explores ALBERT's architecture, its parameter-sharing strategies, and how it achieves efficiency without sacrificing quality. We'll implement the core techniques from scratch and examine the trade-offs involved in building lighter transformer models.

The Parameter Problem

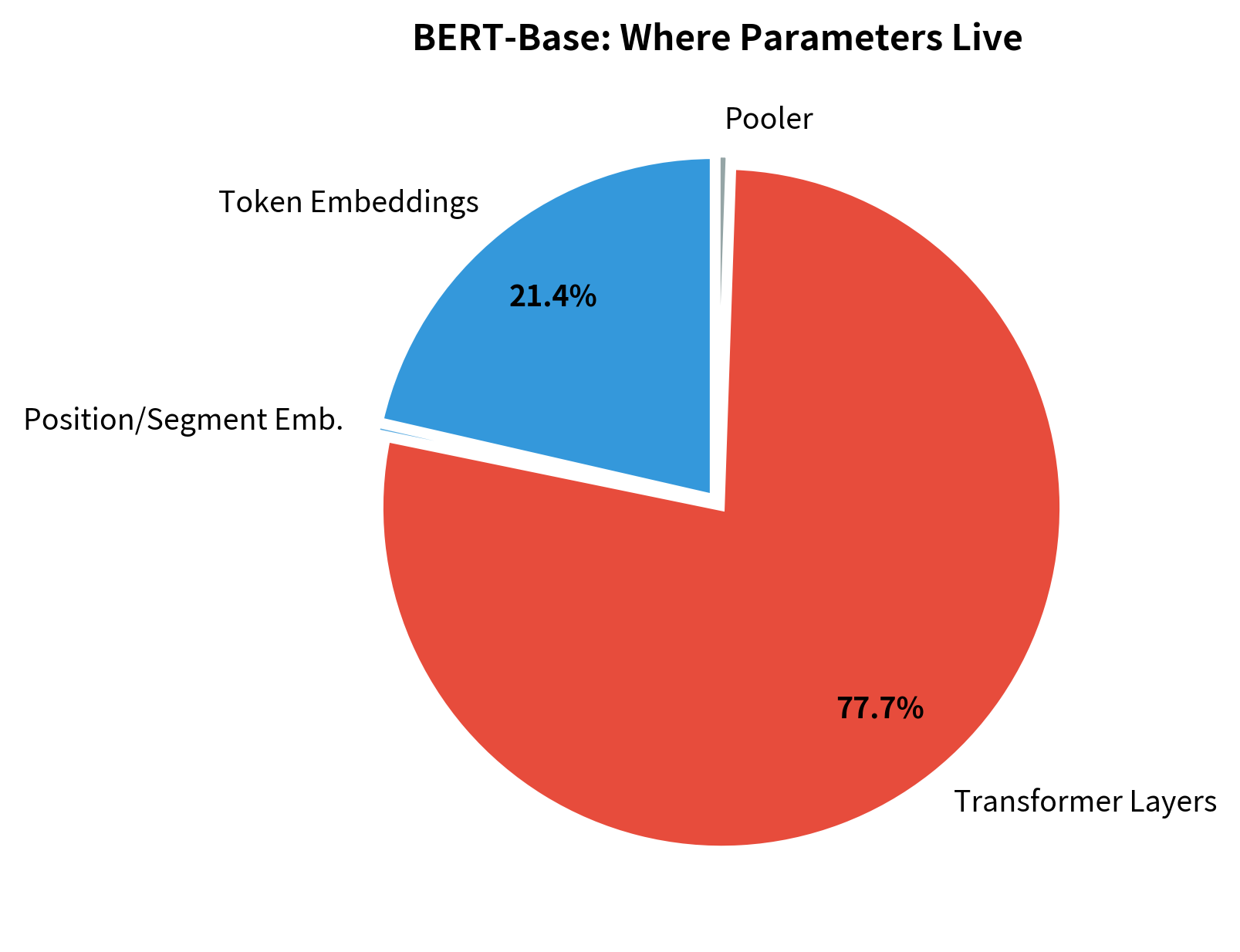

BERT's parameters concentrate in two places: the embedding layer and the transformer blocks. For BERT-Base with a vocabulary of approximately 30,000 tokens and hidden dimension of 768, the embedding matrix alone contains roughly 23 million parameters. That's about 21% of the model's total 110 million parameters, devoted entirely to a lookup table.

The embedding matrix size follows a simple formula: , where is vocabulary size and is hidden dimension. This means larger vocabularies and wider models both inflate embedding costs linearly.

The transformer layers present a different kind of redundancy. Each of BERT's 12 layers has its own attention weights and feed-forward network, but researchers observed that layers often learn similar transformations. The question ALBERT asks: can we share parameters across layers without losing representation quality?

Over 20% of parameters sit in embeddings, while the remaining ~80% are spread across transformer layers. ALBERT targets both sources of redundancy with separate techniques.

Factorized Embedding Parameterization

BERT ties the embedding dimension directly to the hidden dimension. Every token maps to a 768-dimensional vector, which then flows through transformer layers of the same size. This seems natural, but it creates a problem: the embedding matrix grows with vocabulary size and hidden dimension , requiring parameters.

A technique that decomposes the large embedding matrix into two smaller matrices. Instead of mapping tokens directly to hidden-size vectors (), factorized embeddings first map to a smaller intermediate dimension (), then project up to the hidden size (). When , this dramatically reduces parameters.

ALBERT decouples these dimensions. Tokens first embed into a smaller space of dimension , then a linear projection maps them up to the hidden dimension . The parameter count changes from:

to:

where:

- : vocabulary size (number of unique tokens the model can represent)

- : hidden dimension (size of the representations flowing through transformer layers)

- : embedding dimension (smaller intermediate dimension, typically 128)

The first term () represents the token-to-embedding lookup table. The second term () represents the projection matrix that expands embeddings to the hidden size. When , the factorization saves parameters because the expensive vocabulary-sized matrix uses the smaller dimension.

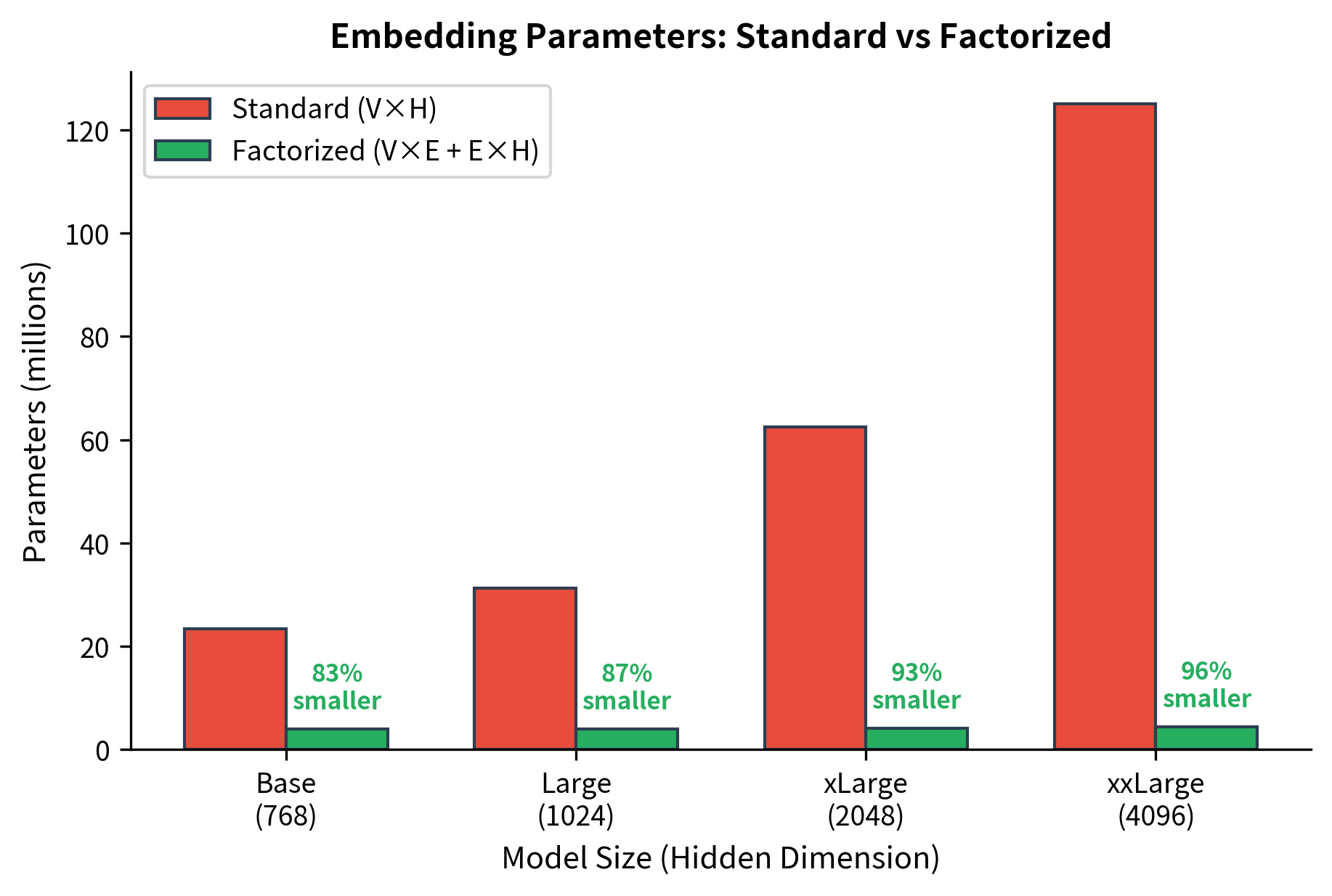

For BERT's vocabulary of 30,522 tokens, hidden size of 768, and an embedding dimension of 128:

That's an 83% reduction in embedding parameters with a single architectural change.

Let's compare parameter counts:

Why Factorization Works

At first glance, reducing embedding dimension seems like it would hurt representation quality. Tokens have less room to encode meaning. But the key insight is that embedding vectors and hidden states serve different purposes.

Token embeddings capture context-independent information. The embedding for "bank" is the same whether it appears in "river bank" or "savings bank." This relatively simple lookup doesn't require the full expressiveness of the hidden dimension, which must capture context-dependent representations built through multiple layers of attention.

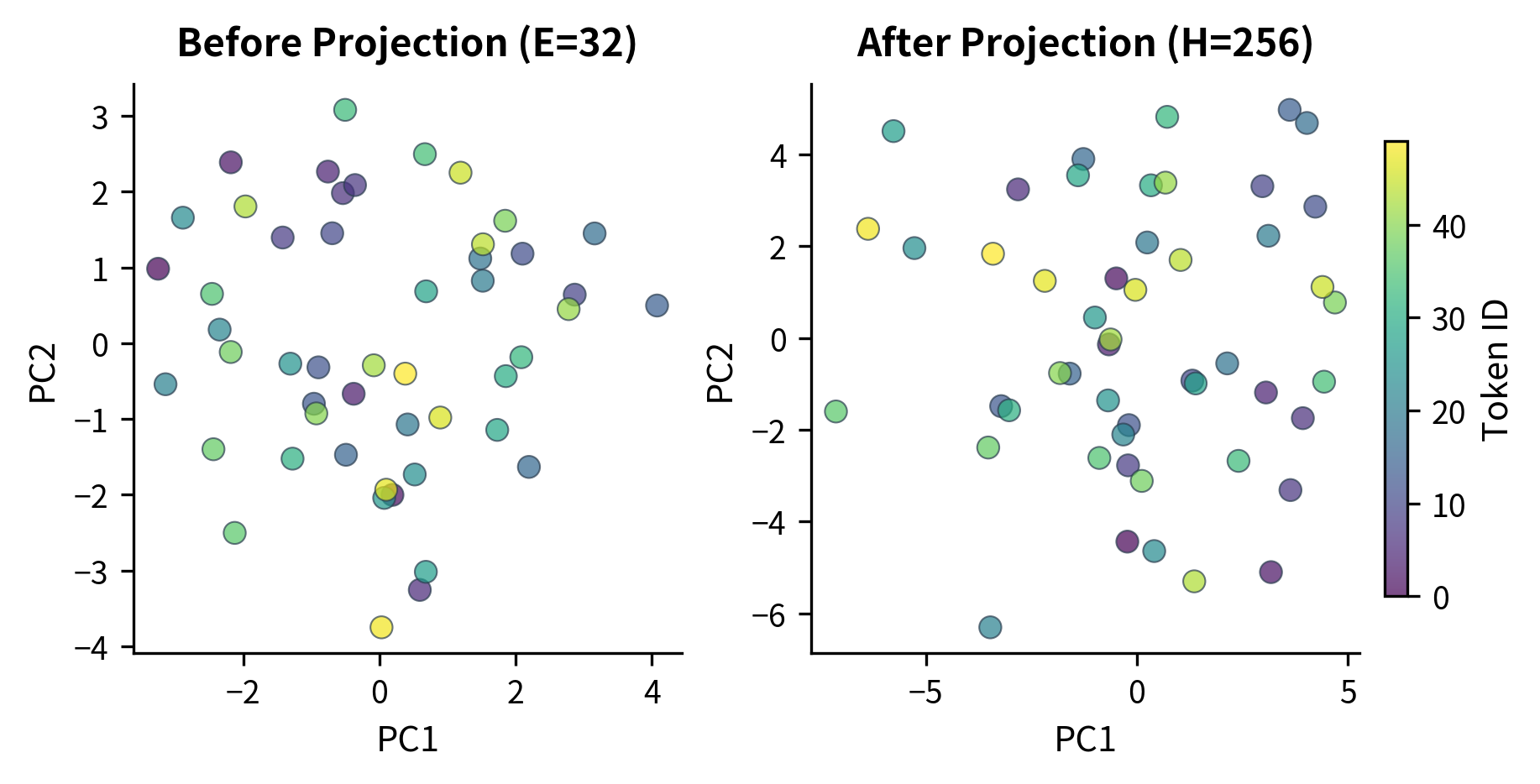

The intermediate representation is 4x smaller than the final output (64 vs 256 dimensions), yet it preserves the information needed for the projection layer to expand it. The variance change shows how the projection redistributes activation magnitudes across the larger hidden space.

The projection layer learns to expand the compressed representations into the full hidden space. During pretraining, this projection adapts to whatever patterns the model needs, effectively learning a task-appropriate decompression of the initial token representations.

We can visualize this by examining how different tokens map through the factorized embedding space:

Cross-Layer Parameter Sharing

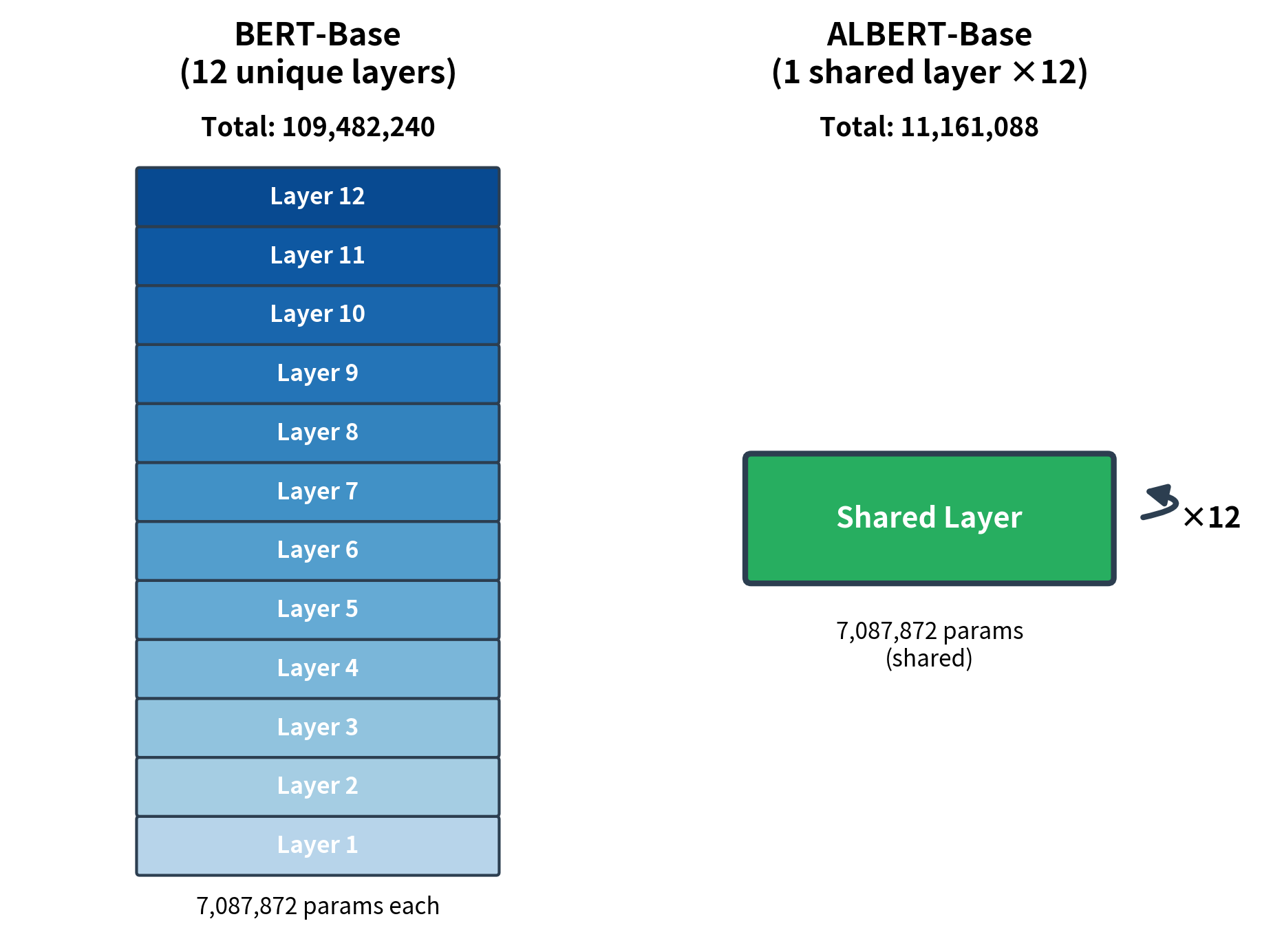

ALBERT's second major innovation is sharing parameters across transformer layers. Rather than each layer having its own attention and feed-forward weights, all layers share a single set of parameters. The model applies the same transformation repeatedly, with only the input changing between iterations.

A technique where transformer layers share the same weight matrices instead of learning independent parameters. This reduces model size proportionally to the number of layers while creating a form of iterative refinement where the same transformation is applied multiple times to progressively update representations.

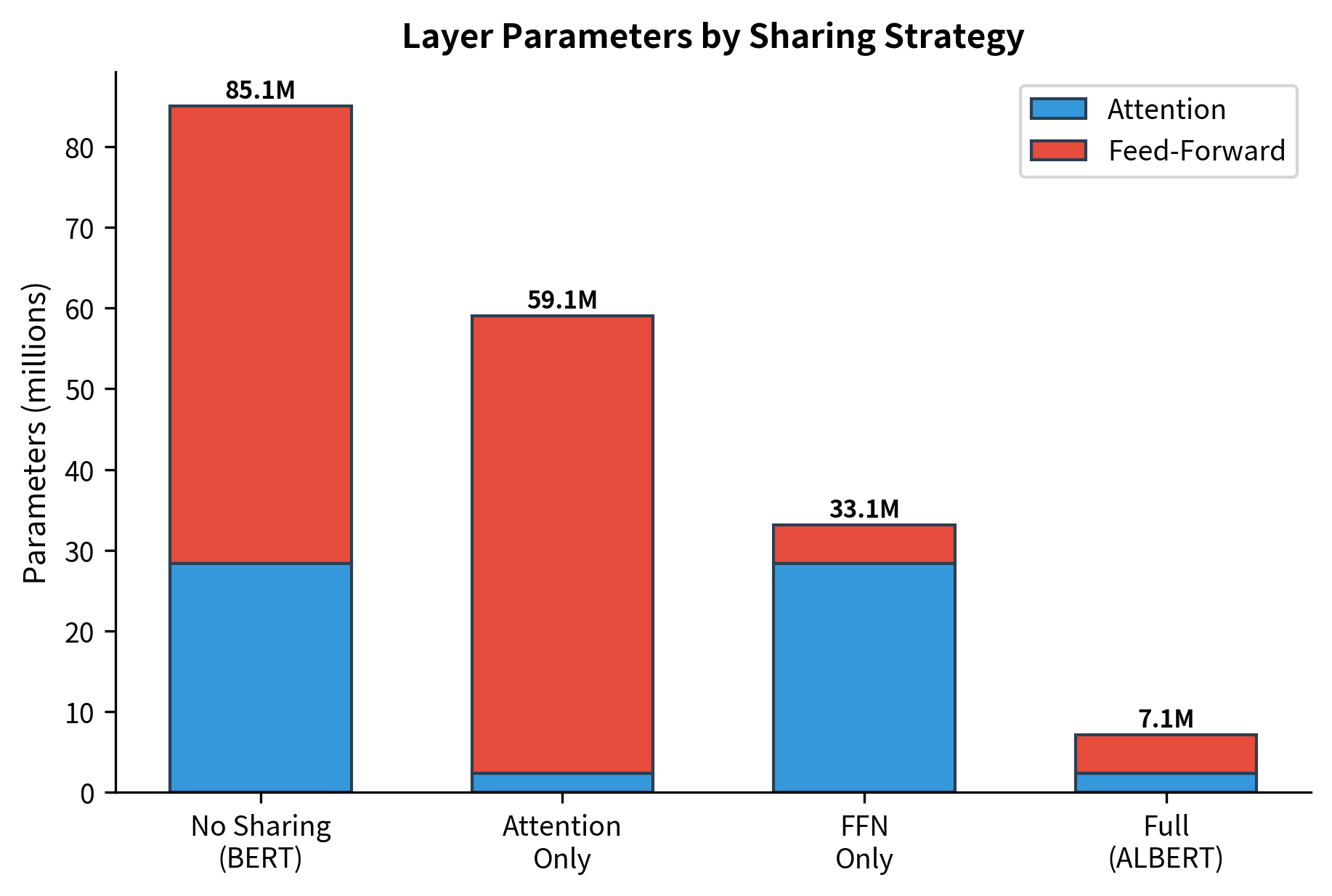

Let's compare the parameter counts:

Different Sharing Strategies

ALBERT's paper explored several sharing strategies beyond full sharing. You can share only attention parameters, only feed-forward parameters, or share everything. The experiments revealed that full sharing works surprisingly well.

Full sharing provides the largest reduction. The ALBERT paper showed that performance degradation from sharing was minimal, particularly for the feed-forward layers. Attention sharing has slightly more impact because different layers benefit from attending to different aspects of the input.

Iterative Refinement

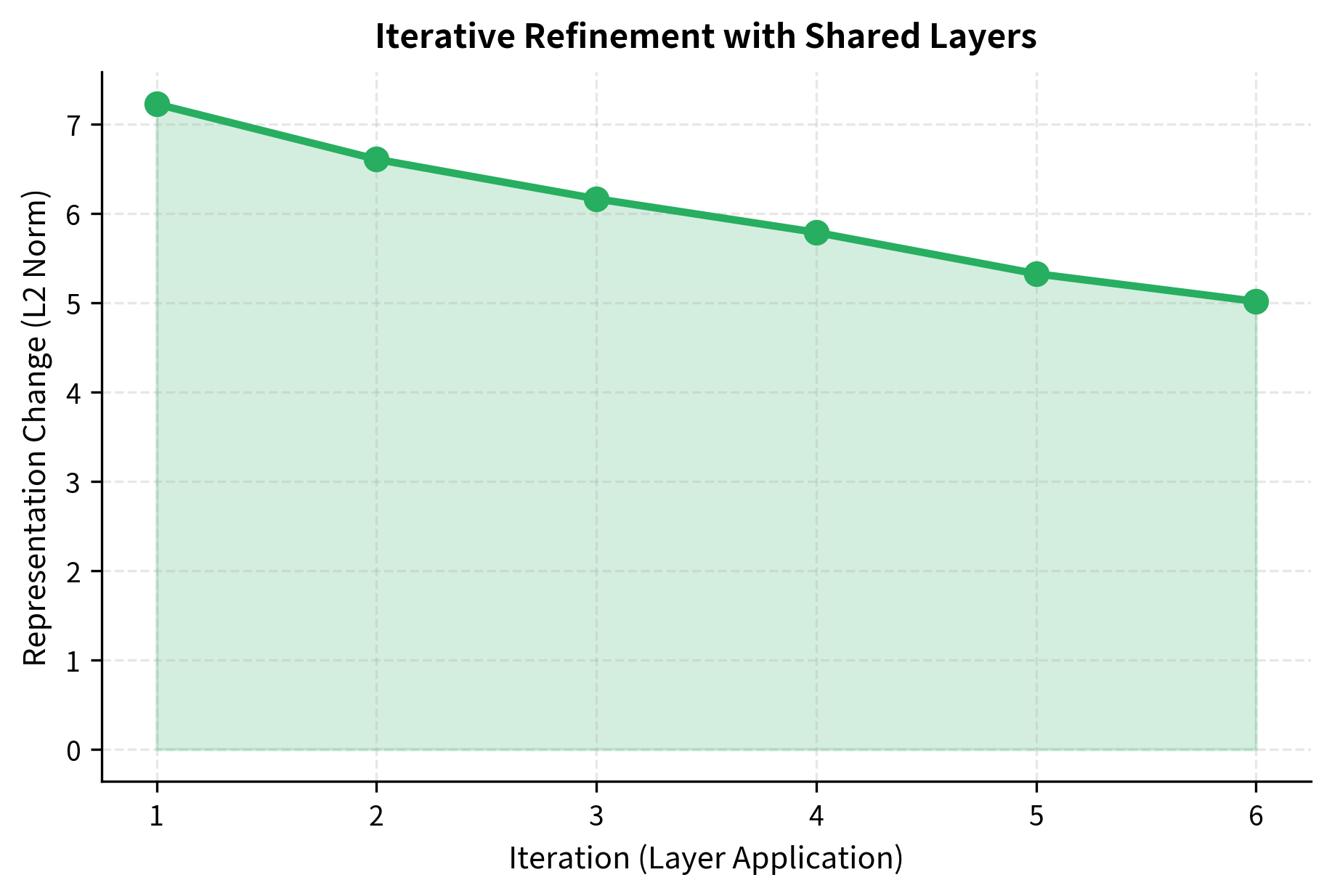

Cross-layer sharing creates an interesting computational pattern. Instead of passing through 12 different transformations, the input passes through the same transformation 12 times. Each iteration refines the representation, similar to how iterative algorithms converge toward a solution.

The representation changes decrease across iterations, indicating that repeated applications of the same layer produce diminishing modifications. This convergence-like behavior suggests the model is iteratively refining toward a stable representation rather than making dramatic changes at each step.

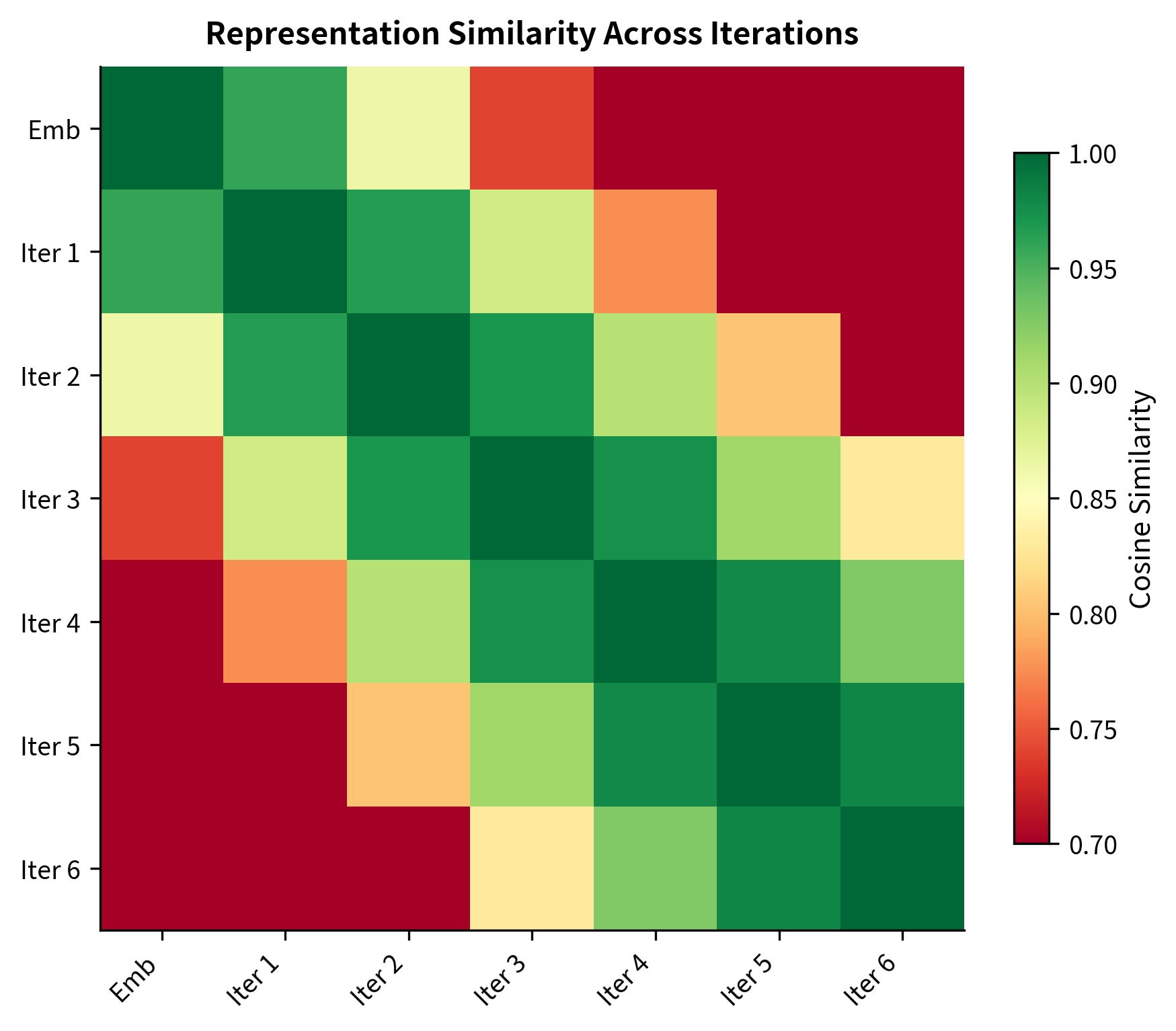

We can visualize how similar representations are across iterations using cosine similarity. If shared layers truly perform iterative refinement, we should see adjacent iterations being more similar than distant ones:

This iterative behavior has theoretical connections to fixed-point computation and recurrent neural networks. The shared layer learns a single step of refinement, and multiple applications accumulate into a complete transformation.

Sentence Order Prediction

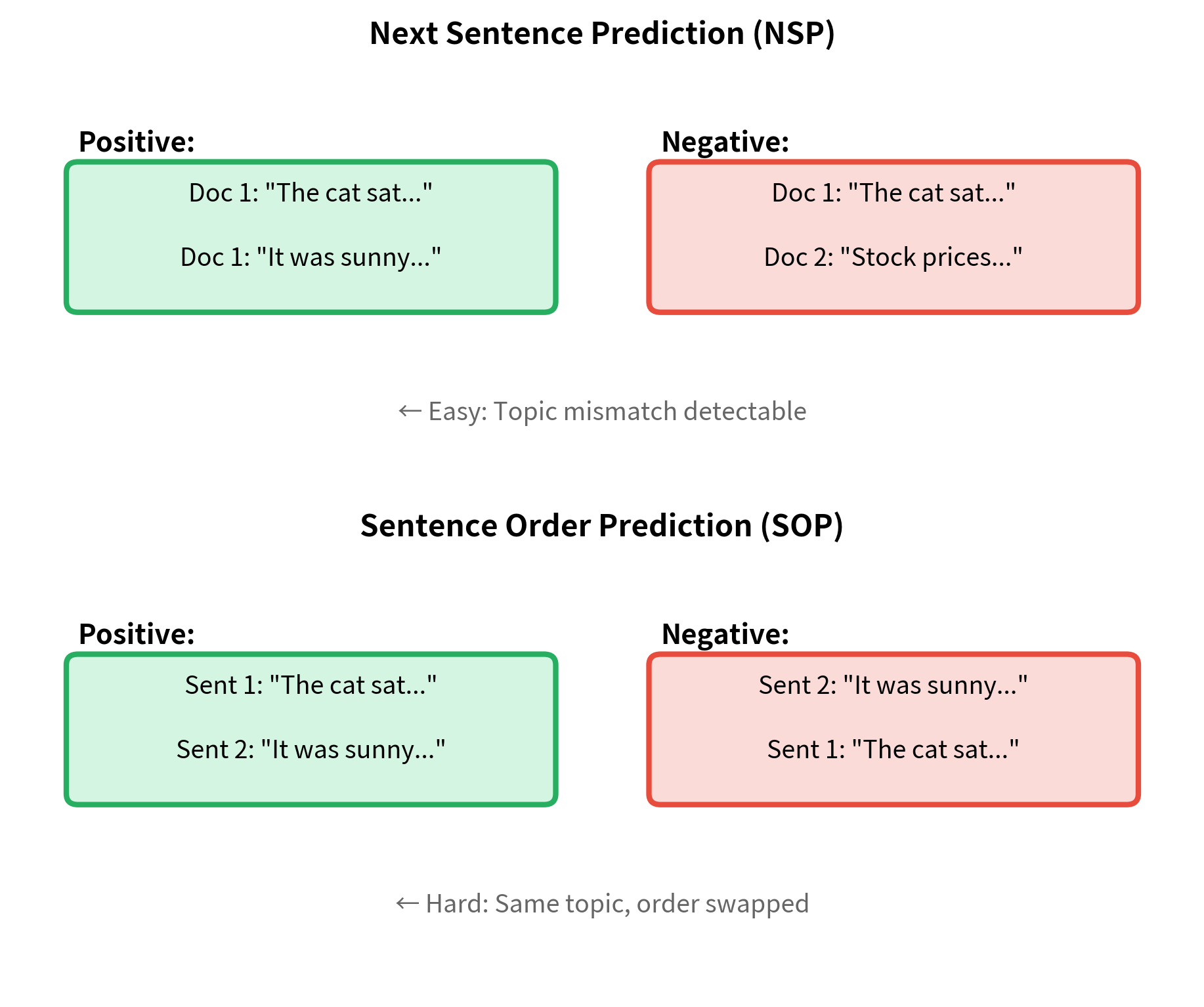

BERT's Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) task asked whether two sentences appeared consecutively in the original document. Critics argued this task was too easy: the model could often succeed by detecting topic consistency rather than understanding inter-sentence coherence.

ALBERT replaced NSP with Sentence Order Prediction (SOP), a harder task. Given two consecutive sentences, SOP asks whether they appear in the correct order or have been swapped.

A pretraining task where the model predicts whether two consecutive sentences appear in their original order or have been swapped. Unlike Next Sentence Prediction, SOP requires understanding discourse coherence since both sentences come from the same document and share the same topic.

SOP is harder than NSP because both sentences always come from the same document. The model cannot rely on topic mismatch to detect negatives. Instead, it must understand temporal and logical relationships between sentences. Does "It fell asleep" make sense before "It watched them lazily"? Only genuine discourse understanding can answer that.

Implementing a Complete ALBERT Model

Let's put together factorized embeddings, shared layers, and the SOP classification head into a complete ALBERT model.

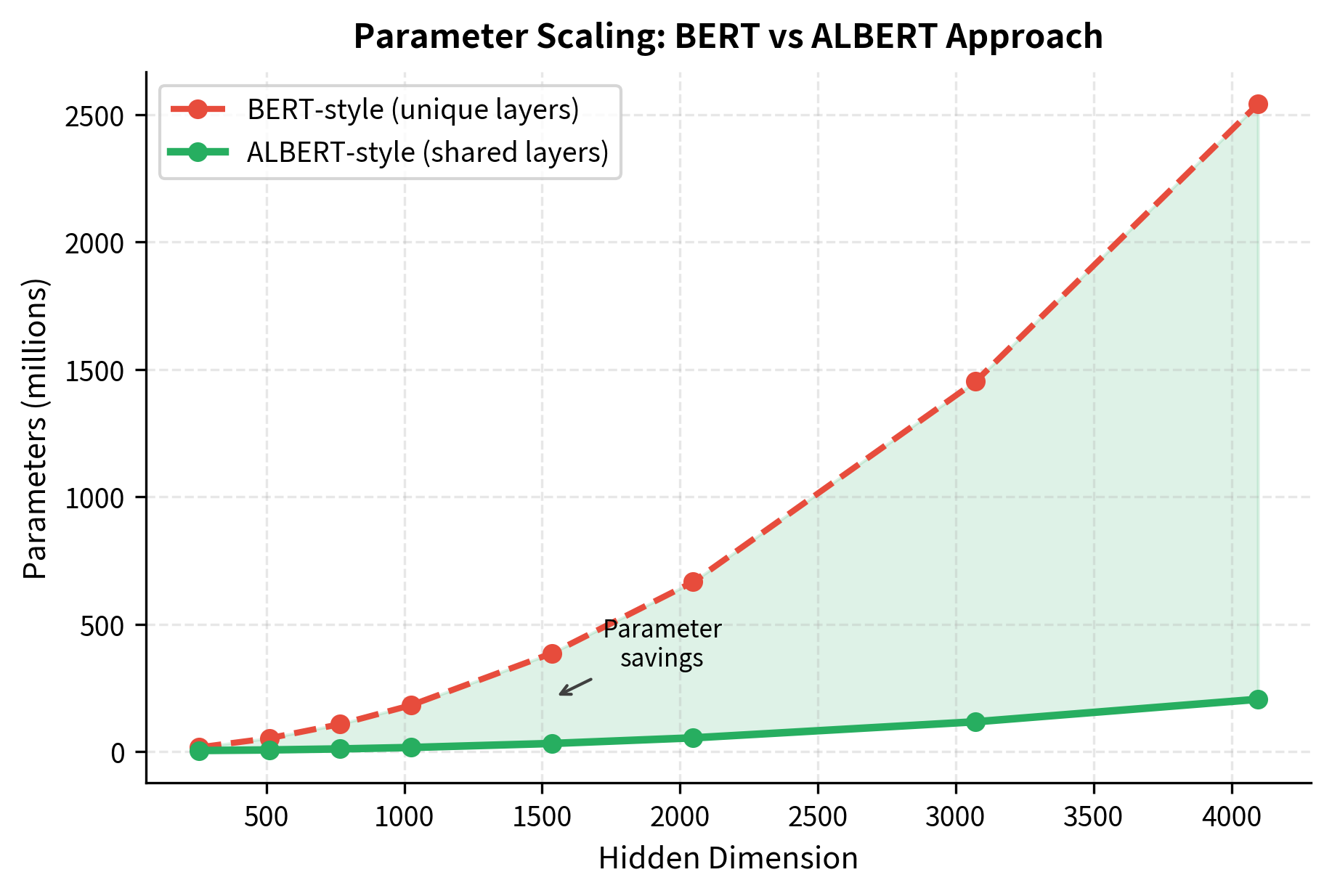

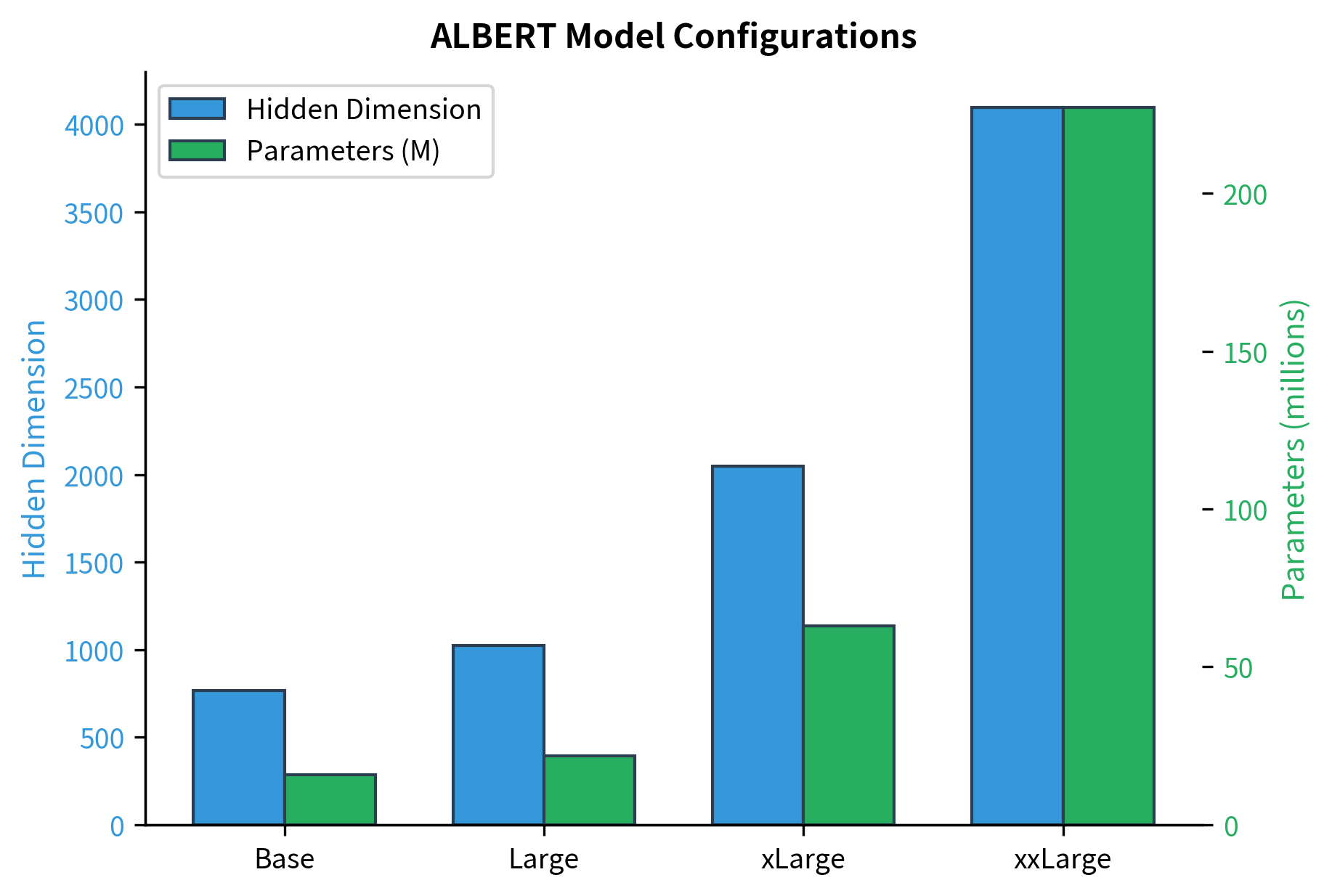

Notice how parameter counts grow much slower than hidden dimensions. ALBERT-xxLarge has a hidden dimension 5.3x larger than ALBERT-Base (4096 vs 768), but its parameter count is only about 20x larger. With BERT's approach, the parameter ratio would match the hidden dimension ratio squared, since attention parameters scale with .

The largest model, ALBERT-xxLarge, uses only 12 layers but has a massive 4096-dimensional hidden space. This reflects the finding that wider models with shared parameters can match deeper models with unique parameters.

We can visualize how differently parameters scale between BERT's approach and ALBERT's:

The MLM loss around 10 is expected for an untrained model predicting among 30,522 vocabulary tokens (random guessing would give ). The SOP loss near 0.69 corresponds to random binary classification (50/50 guessing). Both losses would decrease during actual pretraining as the model learns meaningful patterns.

Memory and Speed Trade-offs

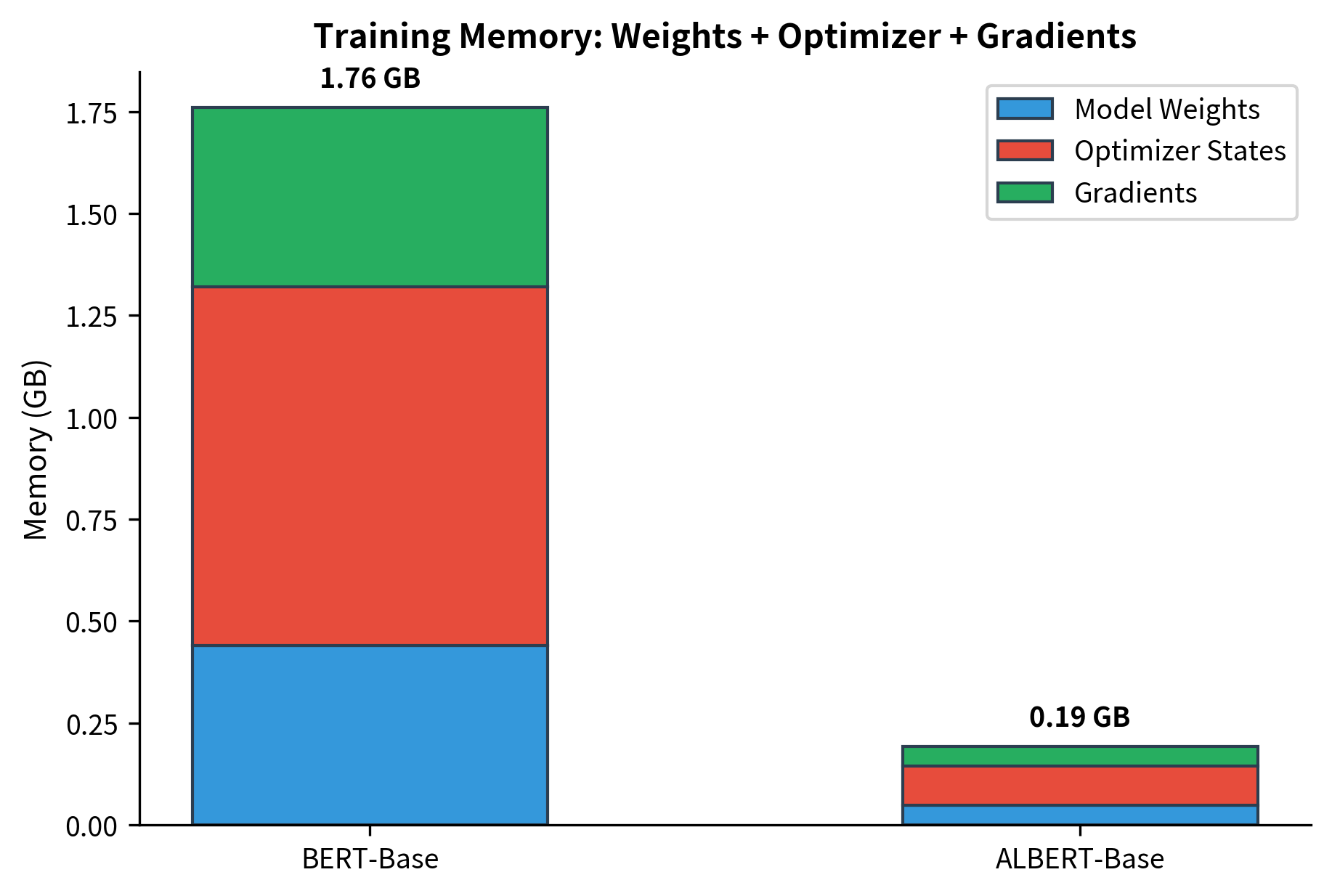

Parameter sharing reduces memory for storing weights but doesn't reduce computation. ALBERT still performs the same number of matrix multiplications as BERT. The savings come from:

- Model storage: The saved model is smaller.

- Gradient memory: Only one set of layer gradients needed.

- Optimizer states: Adam's momentum and variance buffers are smaller.

However, inference speed remains similar because the same operations execute.

Performance Benchmarks

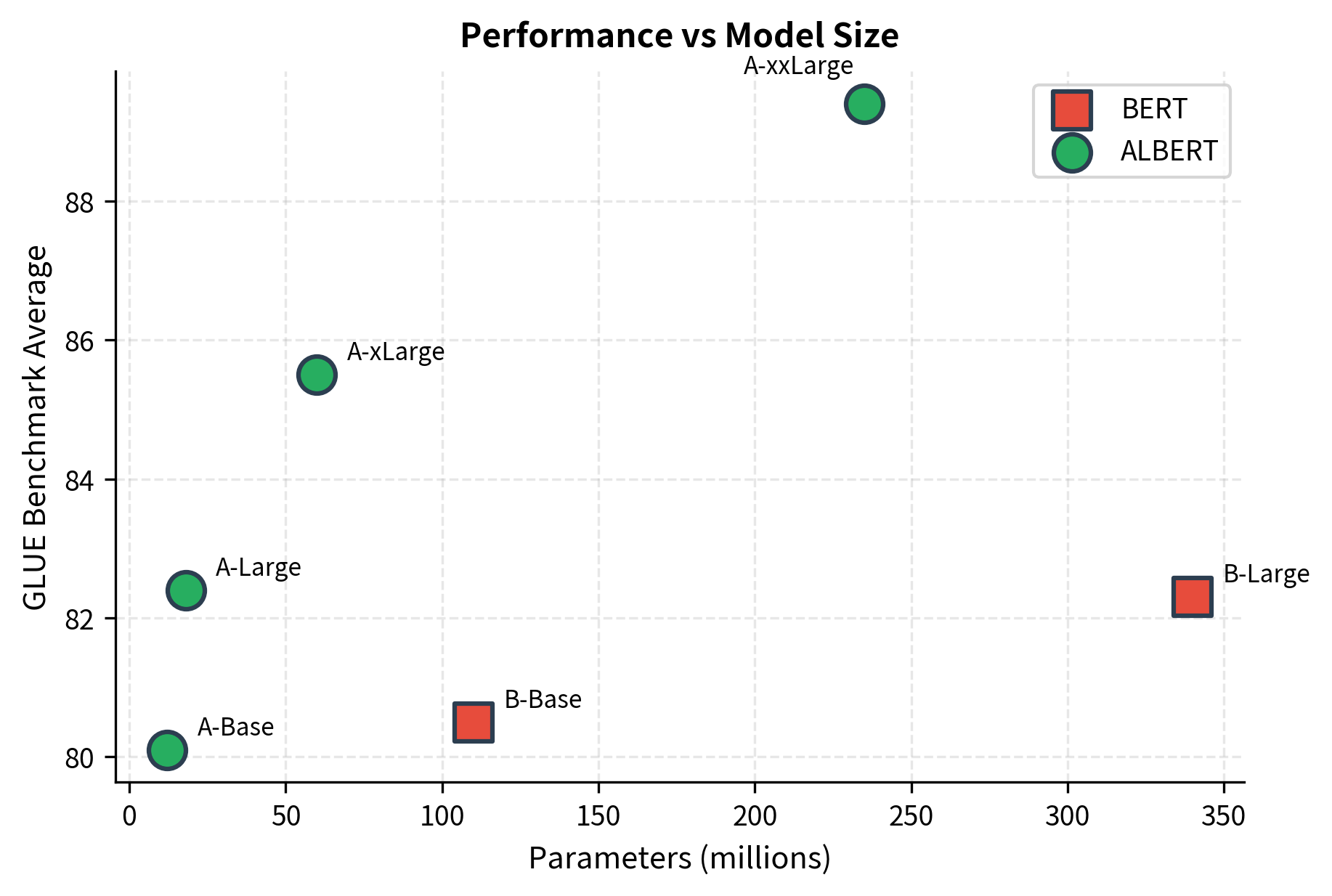

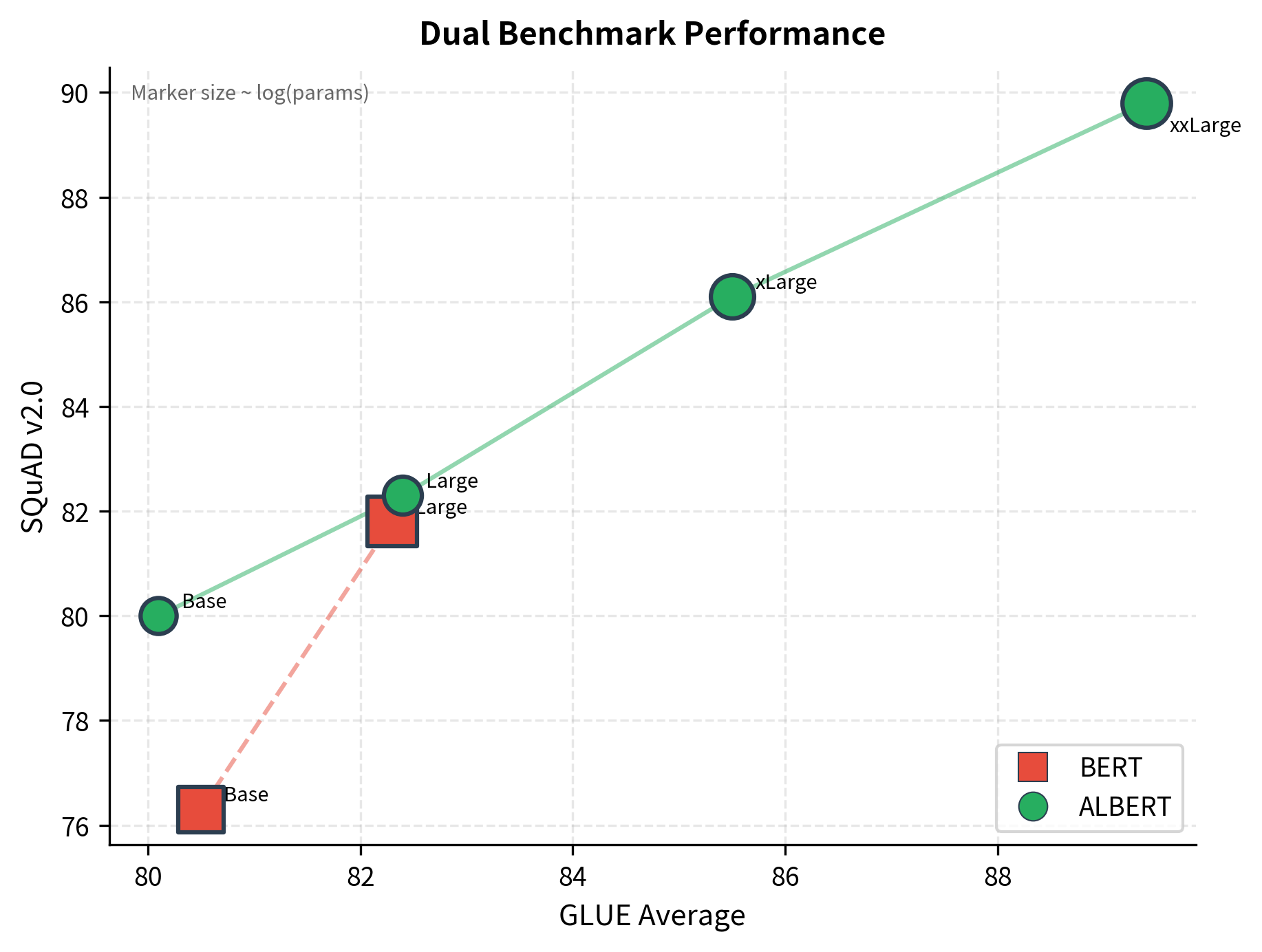

The ALBERT paper demonstrated that smaller models could match or exceed BERT's performance. On GLUE benchmark tasks, ALBERT-xxLarge achieved state-of-the-art results despite having fewer unique parameters than BERT-Large.

The key finding: representation quality depends more on model width and depth of computation than on parameter count. ALBERT's shared parameters still learn effective transformations when applied repeatedly.

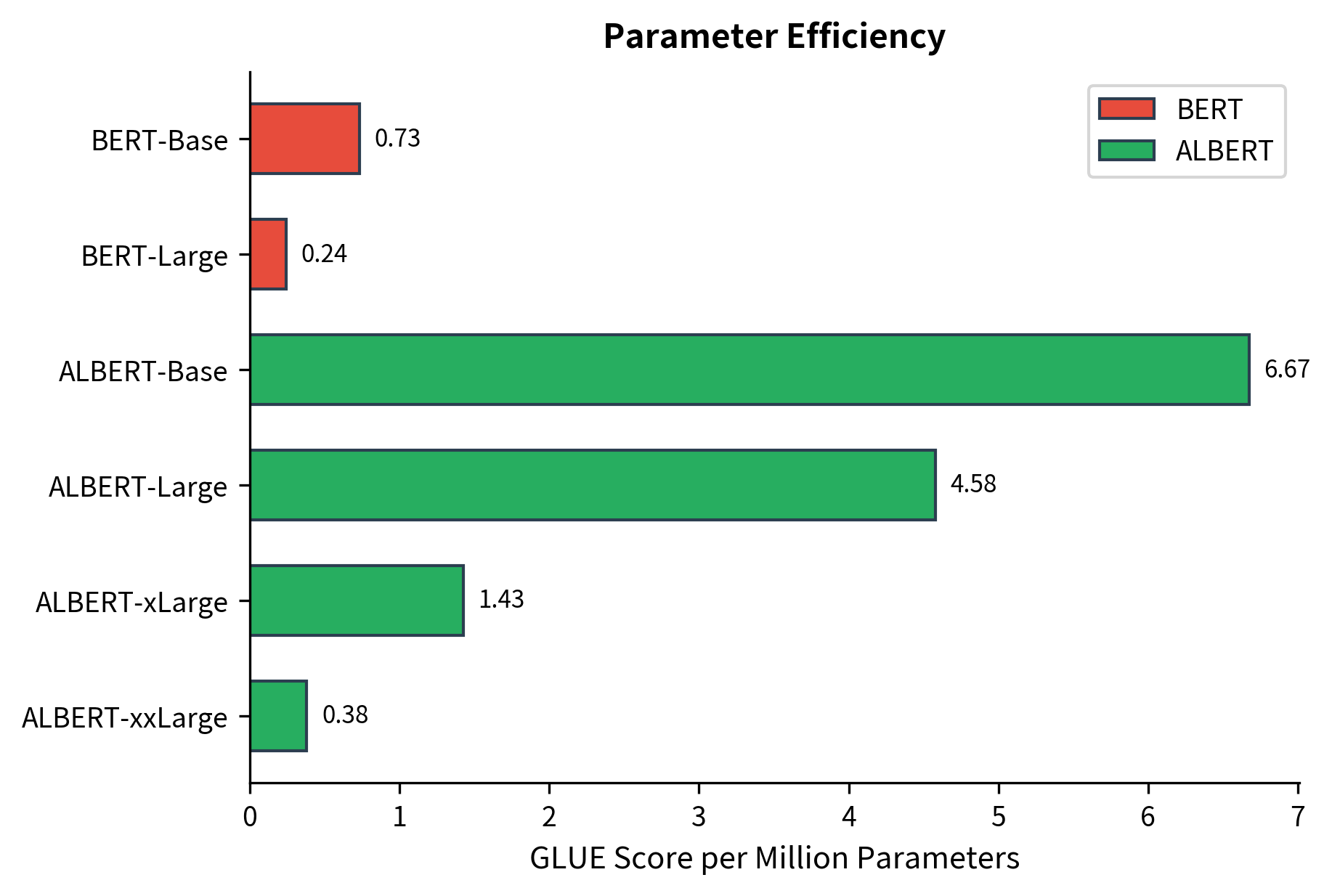

A useful metric for comparing models is parameter efficiency, which measures performance per million parameters. This reveals which architectures extract the most value from their parameters:

When to Use ALBERT

ALBERT shines in specific scenarios:

- Memory-constrained environments: When GPU memory limits model size, ALBERT's smaller parameter count allows training larger effective models.

- Transfer learning: ALBERT's pretrained weights are smaller to download and store.

- Ensemble models: Multiple ALBERT models fit where one BERT might not.

However, ALBERT is not always the best choice:

- Inference latency: Same computational cost as BERT means similar inference time.

- Simple tasks: For easy tasks, smaller unique-parameter models might suffice.

- Maximum performance: At extreme scales, unique parameters can still outperform shared ones.

The following table summarizes these trade-offs:

| Aspect | BERT | ALBERT |

|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 110M (Base), 340M (Large) | 12M (Base), 18M (Large) |

| Training memory | Higher | Lower |

| Inference speed | Same | Same |

| Model file size | Larger | Smaller |

| Layer expressiveness | Unique per layer | Shared across layers |

| Embedding approach | Direct (vocab to hidden) | Factorized (vocab to small, then to hidden) |

Limitations and Impact

ALBERT's innovations come with important caveats that affect practical deployment.

The shared-parameter design creates a fundamental tension. While repeating the same transformation refines representations, it also limits what each pass can do. Unique layers can specialize: early layers might focus on syntax while later layers capture semantics. Shared layers must compromise, learning a transformation that works reasonably well at every depth. For some tasks, this constraint hurts. The original paper showed that very deep ALBERT models sometimes underperform shallower ones because the repeated transformation eventually stops improving representations.

Inference speed remains unchanged despite the smaller parameter count. ALBERT still multiplies inputs by the same-sized weight matrices the same number of times. Memory savings during inference are minimal because activation memory dominates over weight memory. For production systems where latency matters more than storage, ALBERT offers limited advantage over BERT.

The factorized embedding dimension also presents trade-offs. Setting works well empirically, but the optimal value depends on vocabulary size and downstream tasks. Too small an embedding dimension compresses token information too aggressively. The projection layer can only recover what was preserved in the bottleneck.

Despite these limitations, ALBERT's impact on the field was substantial. It demonstrated that parameter efficiency and model quality are not fundamentally opposed. The techniques it introduced, factorized embeddings and cross-layer sharing, appeared in subsequent architectures. Perhaps more importantly, ALBERT challenged the assumption that progress requires ever-larger models. By showing that 12 million parameters could match 110 million, it encouraged research into what models actually need versus what they happen to have.

Key Parameters

When configuring an ALBERT model, these parameters most significantly affect performance and efficiency:

-

embedding_dim: The intermediate embedding dimension before projection to hidden size. ALBERT uses 128 for all model sizes. Smaller values save more parameters but may compress token information too aggressively. Values between 64-256 are reasonable starting points.

-

hidden_dim: The dimension of representations flowing through transformer layers. Larger values increase model capacity but also increase compute cost per layer. ALBERT scales this dimension (768 to 4096) rather than adding unique layers.

-

num_layers: The number of times the shared layer is applied. More applications allow more iterative refinement but increase compute time. With shared parameters, adding layers costs nothing in memory for weights, only activation memory.

-

num_heads: The number of attention heads in multi-head attention. Must divide hidden_dim evenly. More heads allow the model to attend to different aspects of the input simultaneously but increase the attention computation overhead.

-

intermediate_dim: The dimension of the feed-forward network's hidden layer, typically 4x the hidden_dim. Larger values increase the network's capacity to transform representations.

-

dropout: Regularization applied during training. Standard values range from 0.0 to 0.1. Higher dropout can help prevent overfitting but may slow learning.

-

max_position: Maximum sequence length the model can handle. ALBERT uses 512 like BERT. Longer sequences require more memory for attention computation, which scales quadratically with length.

Summary

ALBERT introduced two key innovations for building more efficient transformers:

-

Factorized embeddings decompose the large embedding matrix into two smaller matrices. Instead of directly mapping vocabulary tokens to hidden-dimension vectors (requiring parameters), ALBERT first maps to a smaller embedding space ( parameters) then projects up ( parameters). When the embedding dimension is much smaller than the hidden dimension , this reduces embedding parameters by up to 80%.

-

Cross-layer parameter sharing uses a single set of transformer weights applied repeatedly, cutting layer parameters by a factor equal to the number of layers.

-

Sentence Order Prediction replaces the easier NSP task with order detection, requiring genuine discourse understanding rather than topic matching.

-

Iterative refinement emerges from shared parameters, as the model applies the same transformation multiple times to progressively refine representations.

-

Memory benefits during training come from smaller optimizer states and gradient buffers, though inference speed matches BERT due to identical computation.

-

Performance parity demonstrated that model quality depends more on computational depth and width than on unique parameter count, with ALBERT-xxLarge achieving state-of-the-art results.

ALBERT showed that careful architecture design could dramatically reduce model size without sacrificing performance, influencing subsequent work on efficient transformers.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about ALBERT's parameter-efficient architecture.

Comments