Master prefix LM, the hybrid pretraining objective that enables bidirectional prefix understanding with autoregressive generation. Covers T5, UniLM, and implementation.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Prefix Language Modeling

What if you could have the best of both worlds? Causal language modeling excels at generation but sees only left context. Masked language modeling captures bidirectional context but cannot generate text autoregressively. Prefix Language Modeling (Prefix LM) bridges this gap by treating part of the input bidirectionally and the rest causally, enabling models that both understand context deeply and generate fluently.

The key insight is simple: when generating a continuation of a prompt, the prompt itself is fully known. There's no reason to hide later prompt tokens from earlier ones. Only the generation, which unfolds token by token, requires causal masking. Prefix LM formalizes this intuition into a training objective that powers models like T5, UniLM, and UL2.

In this chapter, we'll explore the prefix LM formulation, understand its distinctive attention pattern, implement the objective from scratch, and examine how it enables unified models for both understanding and generation.

The Prefix LM Intuition

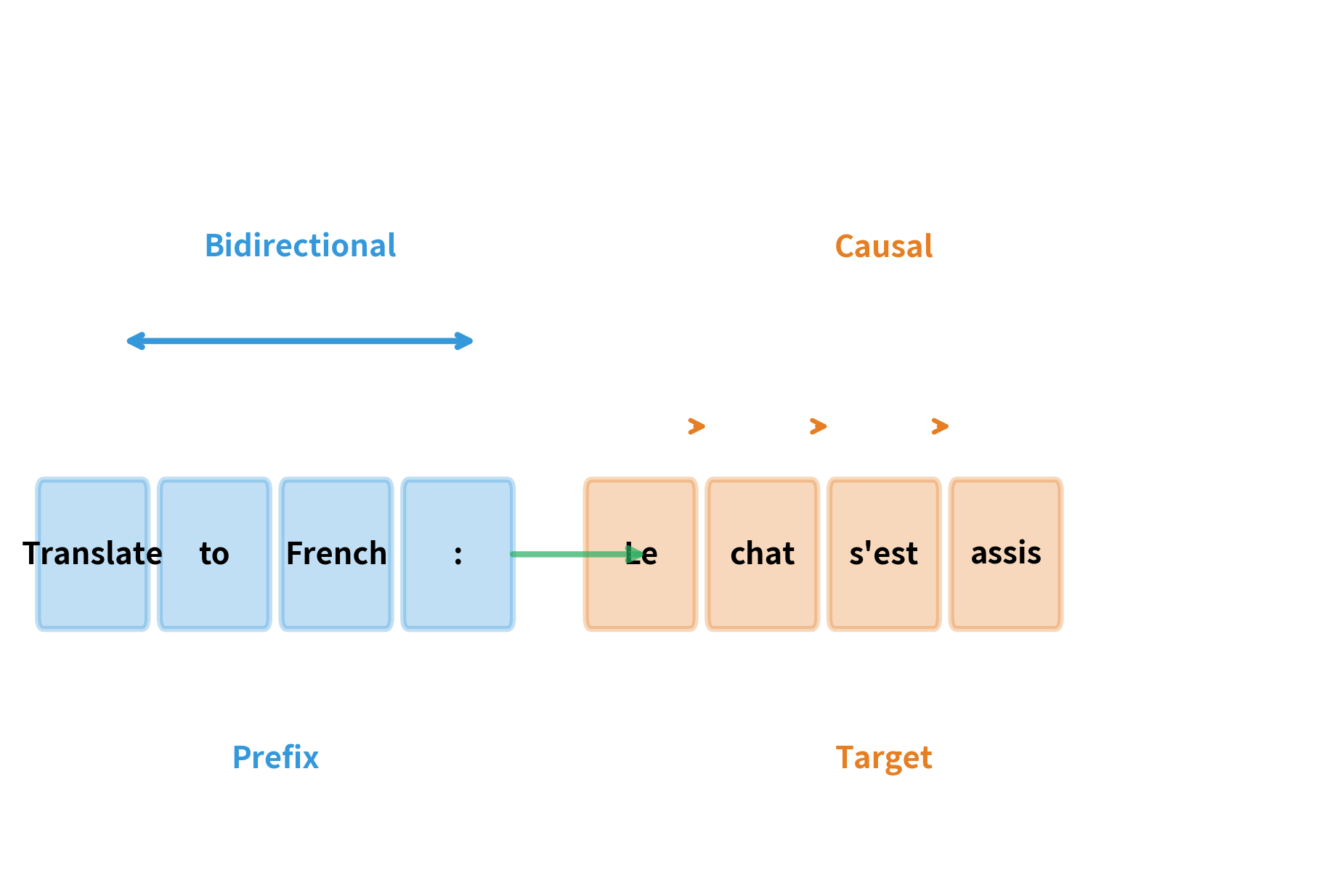

Consider a translation task: "Translate to French: The cat sat on the mat." The input prompt is complete and known. When generating "Le chat s'est assis sur le tapis," each French word depends on the entire English prompt plus previously generated French words. There's no benefit to hiding "mat" from "cat" in the English prompt.

Prefix LM captures this asymmetry. The sequence is split into two parts:

- Prefix: The conditioning context (prompt, input, instruction). Tokens here can attend to each other bidirectionally.

- Target: The continuation to be generated. Tokens here can attend to the full prefix plus their own left context, following causal constraints.

This hybrid attention pattern preserves the generation capability of causal LM while allowing richer representation of the prefix through bidirectional attention.

This structure matches many real-world scenarios. In question answering, the question is the prefix and the answer is the target. In summarization, the document is the prefix and the summary is the target. In dialogue, the conversation history is the prefix and the next response is the target. The bidirectional prefix captures the full context, while the causal target enables coherent generation.

The Prefix LM Objective

Now that we understand the intuition behind splitting sequences into prefix and target regions, we need a formal training objective. The key question is: how do we mathematically express what we want the model to learn?

From Intuition to Formalization

Think about what happens when you complete someone's sentence. You don't just hear the first word and guess; you take in the entire context they've provided, then generate a continuation that fits seamlessly. Prefix LM captures exactly this: the model should fully understand the prefix before generating the target.

This leads to two requirements that our objective must encode:

- Full prefix visibility: When predicting any target token, the model should have access to the complete prefix, not just the tokens that came before.

- Causal target generation: Target tokens should be generated left-to-right, each depending on previous target tokens but not future ones.

The Mathematical Formulation

Consider a sequence divided at position into two parts: the prefix and the target . The training objective minimizes the negative log-likelihood of predicting target tokens:

where:

- : the prefix language modeling loss to minimize

- : the total sequence length

- : the position where the prefix ends and the target begins (the split point)

- : the prefix tokens , which are fully visible bidirectionally

- : the target tokens generated before position , specifically

- : the probability the model with parameters assigns to token , conditioned on the full prefix and all preceding target tokens

- The summation iterates only over target positions, from to

Understanding the Conditioning

The heart of this formula lies in the conditioning term . Let's unpack what this means for a concrete example.

Suppose we have the sequence "The cat sat on the mat" with (prefix is "The cat sat"). When predicting the fourth word "on":

- The model sees: all of "The cat sat" (bidirectionally) + nothing yet from the target

- When predicting "the": sees "The cat sat" + "on"

- When predicting "mat": sees "The cat sat" + "on the"

Notice the asymmetry: prefix tokens are always fully visible, while target tokens accumulate causally. This is the mathematical expression of the L-shaped attention mask we'll implement shortly.

Why Loss on Target Only?

The loss summation starts at , not at 1. This means we compute loss only on target tokens, ignoring prefix tokens entirely. Why?

The prefix is given as input at inference time. Asking the model to predict prefix tokens would be like testing whether someone can recite back what you just told them. That's not the skill we want to develop. Instead, we focus all learning signal on the generation task: given this context, what comes next?

This differs from causal LM, where every position contributes to the loss. In prefix LM, the prefix serves purely as conditioning context, its representation is refined through gradient flow, but no direct prediction loss applies to it.

A pretraining objective that splits sequences into a prefix with bidirectional attention and a target with causal attention. The model learns to generate the target conditioned on the full bidirectional context of the prefix, combining the representational power of encoder-style models with the generation capability of decoder-style models.

The Prefix LM Attention Pattern

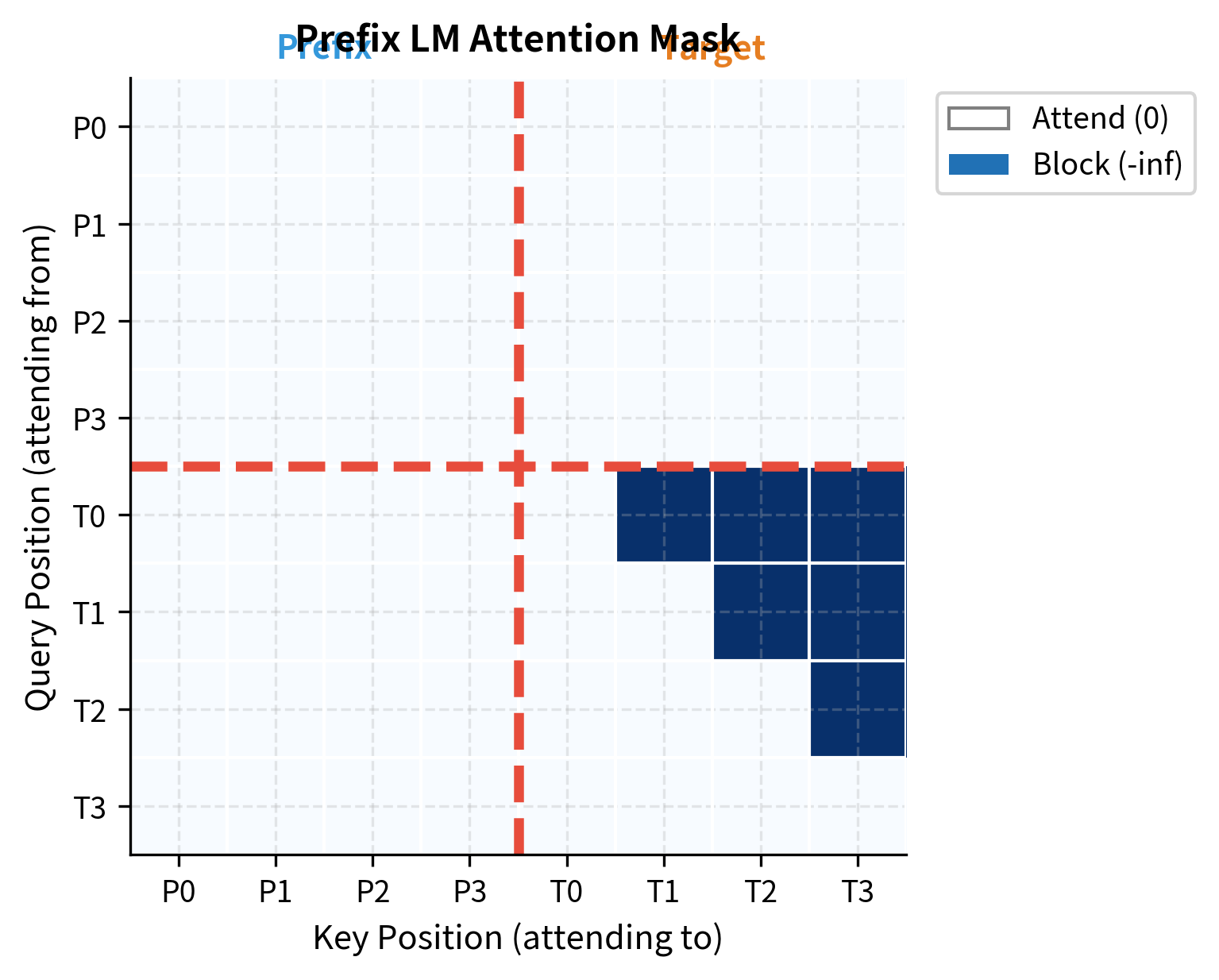

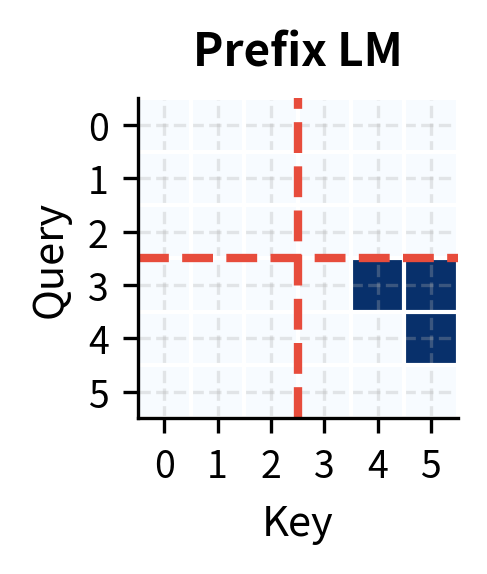

The mathematical objective we just defined has a direct physical manifestation: the attention mask. This mask controls which tokens can "see" which other tokens during the forward pass, and it must encode our two key requirements: bidirectional prefix and causal target.

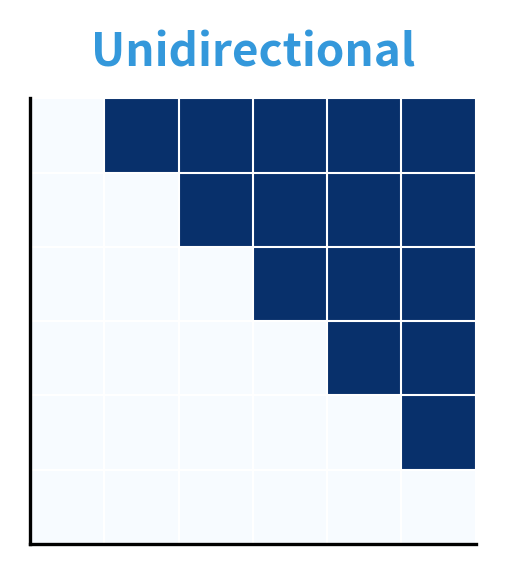

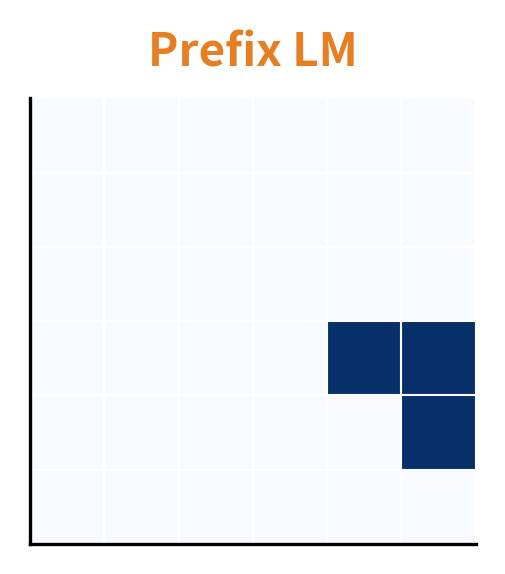

Unlike the uniform lower-triangular mask of causal LM or the full-attention mask of masked LM, prefix LM uses a hybrid pattern that changes behavior partway through the sequence.

Anatomy of the Attention Mask

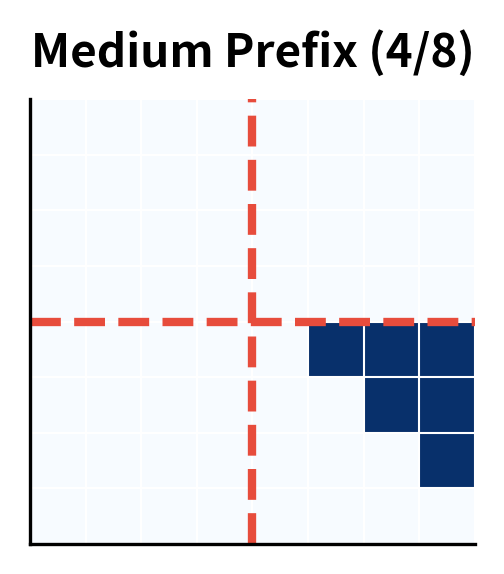

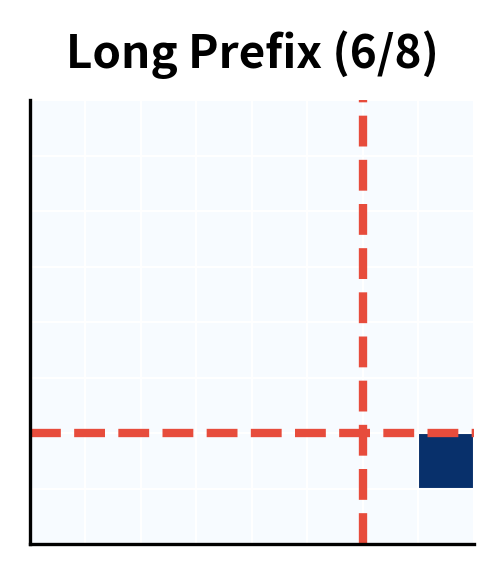

The mask divides naturally into three regions, each serving a distinct purpose:

- Prefix-to-prefix (upper-left quadrant): Full bidirectional attention. Every prefix token attends to every other prefix token, and can also attend to all target positions. This is what gives the prefix its representational richness, as each word can incorporate context from the entire sequence.

- Target-to-prefix (lower-left rectangle): Full attention. Every target token attends to all prefix tokens. This is how the conditioning flows, when generating "Le" in our translation example, the model can look back at any part of "Translate to French: The cat sat on the mat."

- Target-to-target (lower-right quadrant): Causal attention. Each target token attends only to itself and preceding target tokens. This preserves the autoregressive property needed for generation, you can't peek at future words you haven't generated yet.

Together, these regions create the characteristic L-shaped pattern visible in the mask visualization. The prefix forms a fully connected subgraph where information flows freely in all directions, while the target maintains causal structure that enables token-by-token generation.

Implementing the Mask

Translating this pattern into code requires building a matrix where each entry indicates whether position can attend to position :

The first four positions (prefix) have all zeros, meaning they attend to everything. Positions 4-7 (target) have zeros up to and including their own position, then negative infinity to block future tokens.

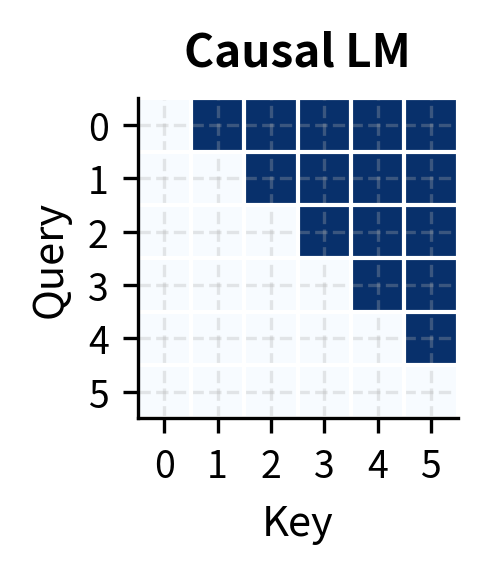

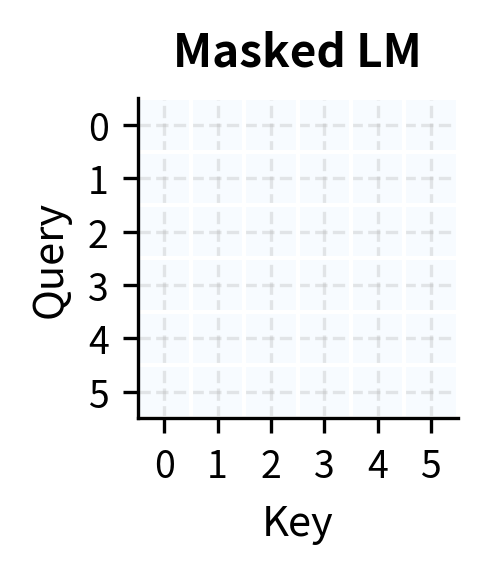

Comparing Attention Patterns

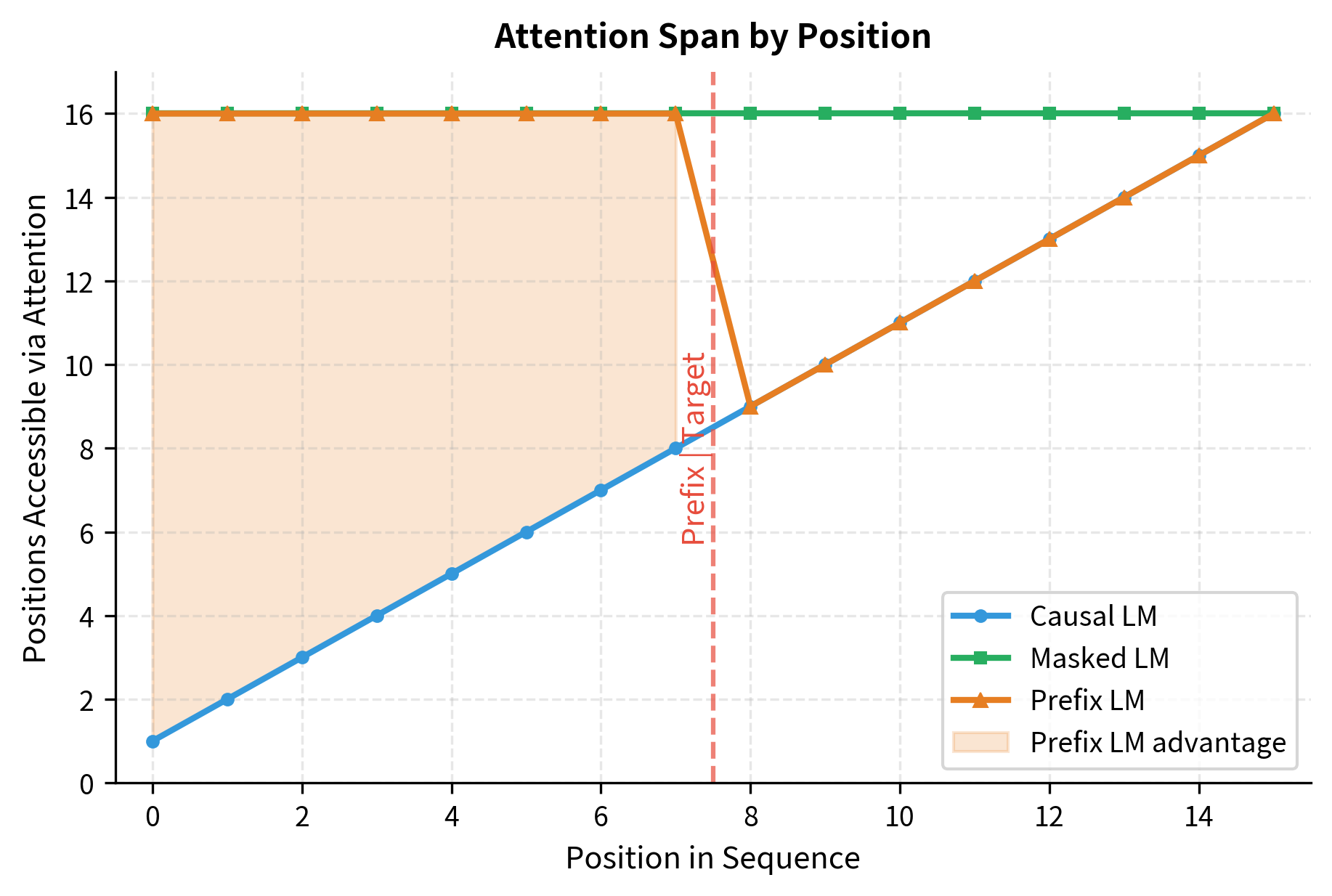

To understand prefix LM's unique position, let's compare it with causal and masked LM attention patterns:

The visual comparison reveals the key differences:

| Aspect | Causal LM | Masked LM | Prefix LM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefix attention | Causal | Bidirectional | Bidirectional |

| Target attention | Causal | Bidirectional | Causal |

| Generation | Yes | No | Yes |

| Context richness | Limited | Full | Hybrid |

| Use case | Pure generation | Understanding | Conditioned generation |

Prefix LM occupies the middle ground. It enables generation like causal LM while providing richer prefix representations like masked LM.

This plot quantifies the representational advantage of prefix LM. In the prefix region (positions 0-7), each token has full access to all 16 positions, just like masked LM. In the target region (positions 8-15), the attention span follows the causal pattern, growing linearly. The shaded area represents the additional context each prefix position gains compared to causal LM, which translates to richer representations that inform target generation.

Implementing Prefix LM Training

With the mathematical foundation and attention pattern in place, we can now build a complete prefix LM from scratch. This implementation brings together everything we've discussed: the hybrid attention mask, the target-only loss computation, and the conditioning structure that makes prefix LM unique.

We'll construct the model in three stages: first the attention mechanism that applies our L-shaped mask, then the full transformer architecture, and finally the loss function that focuses learning on target positions.

The Attention Mechanism

The core innovation happens in the attention layer. We need to apply the prefix LM mask during the attention computation, ensuring that information flows according to our bidirectional-prefix, causal-target pattern:

The key line is scores = scores + mask. By adding negative infinity to positions we want to block, the subsequent softmax converts those positions to zero probability. The mask is created dynamically based on prefix_len, allowing different sequences in a batch to have different split points.

The Complete Model

Now we wrap this attention mechanism in a full transformer architecture. The model includes embeddings, multiple transformer layers with our prefix LM attention, and an output projection to vocabulary logits:

Notice how compute_prefix_lm_loss implements the target-only loss from our mathematical formulation. By slicing logits[:, prefix_len:, :], we extract only the predictions for target positions. The model produces logits for all positions (including the prefix), but we discard the prefix predictions when computing the loss, focusing the learning signal entirely on the generation task.

The model applies prefix LM attention in each layer, passing the prefix length to determine where the bidirectional/causal boundary lies. This is more flexible than hardcoding the mask, as different examples in a batch could have different prefix lengths.

Training on Prefix-Target Pairs

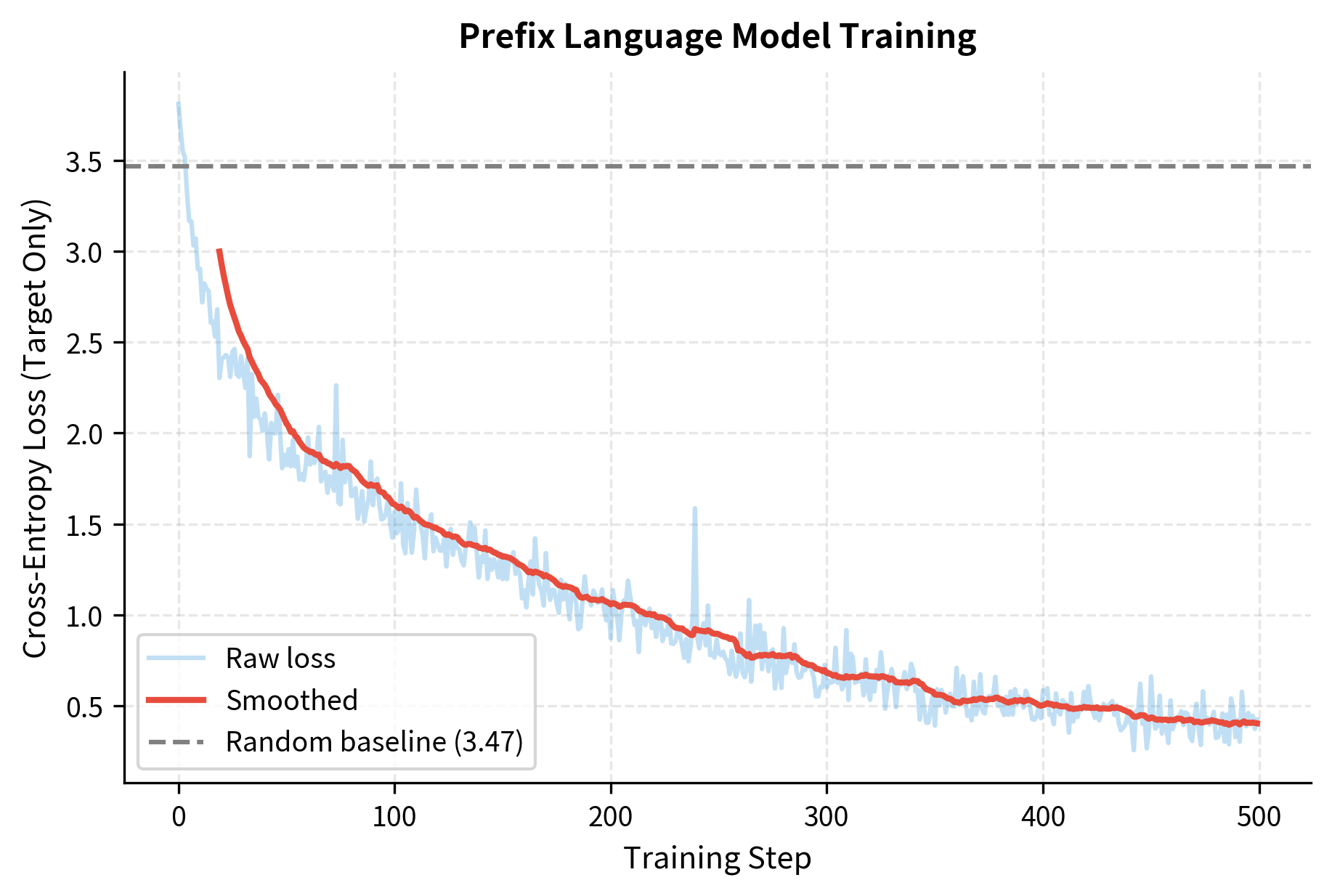

With our model architecture complete, we can now see prefix LM in action. We'll train on a simple task: given the first part of a sentence (the prefix), generate a plausible continuation (the target). Character-level tokenization keeps things interpretable, letting us watch the model learn character-by-character patterns.

Preparing the Data

First, we create a small corpus and tokenize it at the character level:

This tiny corpus is far smaller than what you'd use for real pretraining, but it's enough to demonstrate the mechanics. The vocabulary of unique characters becomes our token space.

The Training Loop with Random Splits

A key design choice in prefix LM training is how to select the split point. We could fix it (always split at position 10), but that would limit generalization. Instead, we randomize the prefix length within a reasonable range. This teaches the model to handle varying amounts of context:

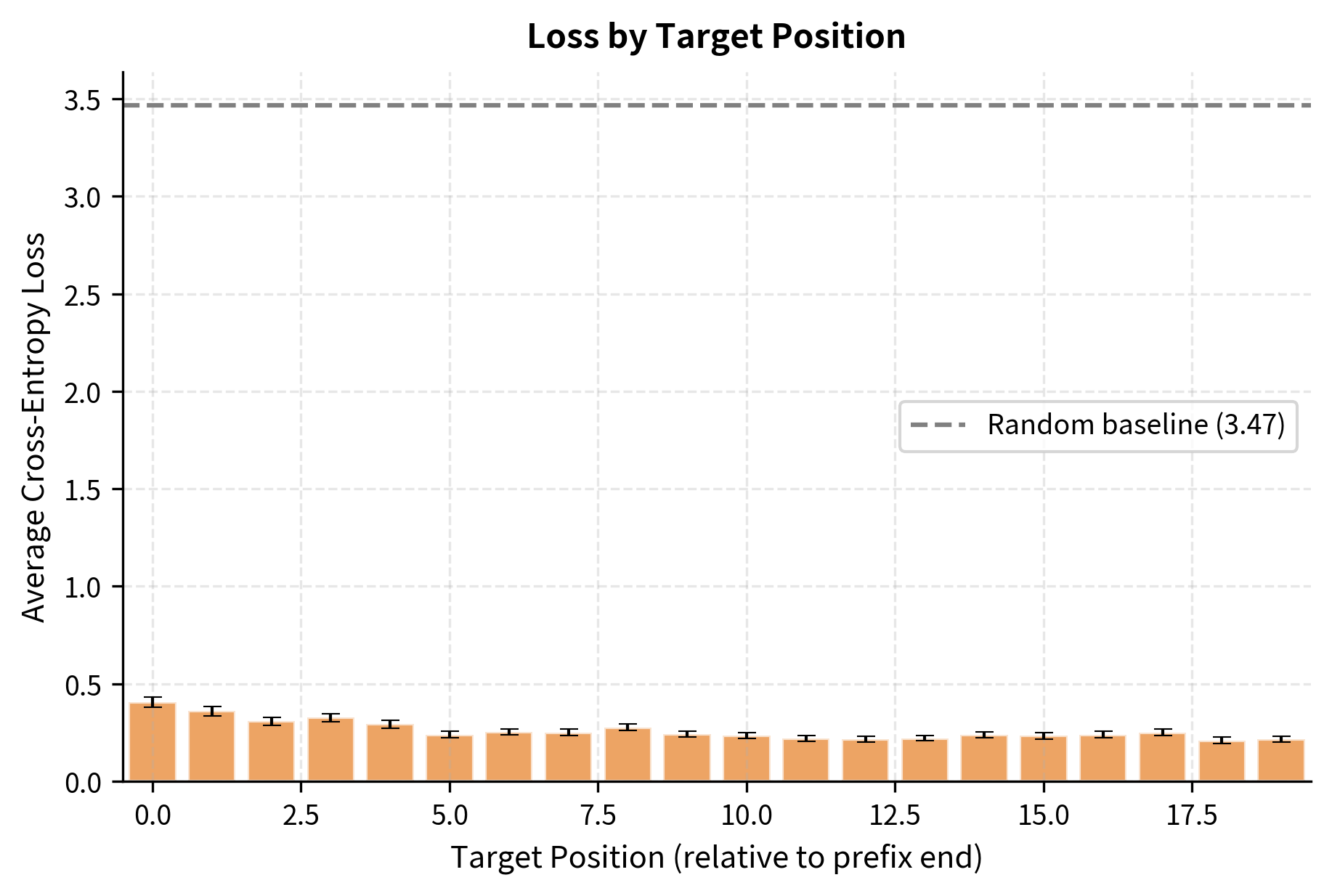

The loss dropped substantially from the random baseline, indicating the model has learned meaningful patterns. A random model would assign equal probability to each token, yielding loss near the random baseline. The significant reduction shows the model is successfully using the bidirectional prefix context to improve target predictions.

The model learns to generate continuations conditioned on the prefix. Unlike standard causal LM where loss is computed everywhere, prefix LM focuses the learning signal on the generation task. The prefix serves as rich context, processed bidirectionally, that informs the target generation.

The per-position loss analysis reveals an important pattern: the first few target positions often achieve lower loss than later positions. This makes intuitive sense, the first target token has direct access to the full bidirectional prefix, while later tokens must rely increasingly on autoregressively generated context, which may be less informative than the original prefix.

Generation with Prefix LM

Let's generate text using our trained prefix LM. The key difference from causal generation is that we start with a bidirectional prefix:

The generation process treats the prefix specially: those tokens can attend to each other bidirectionally throughout generation. As new tokens are added, they see the full prefix context plus their left context, following the prefix LM pattern.

Visualizing Learned Attention Patterns

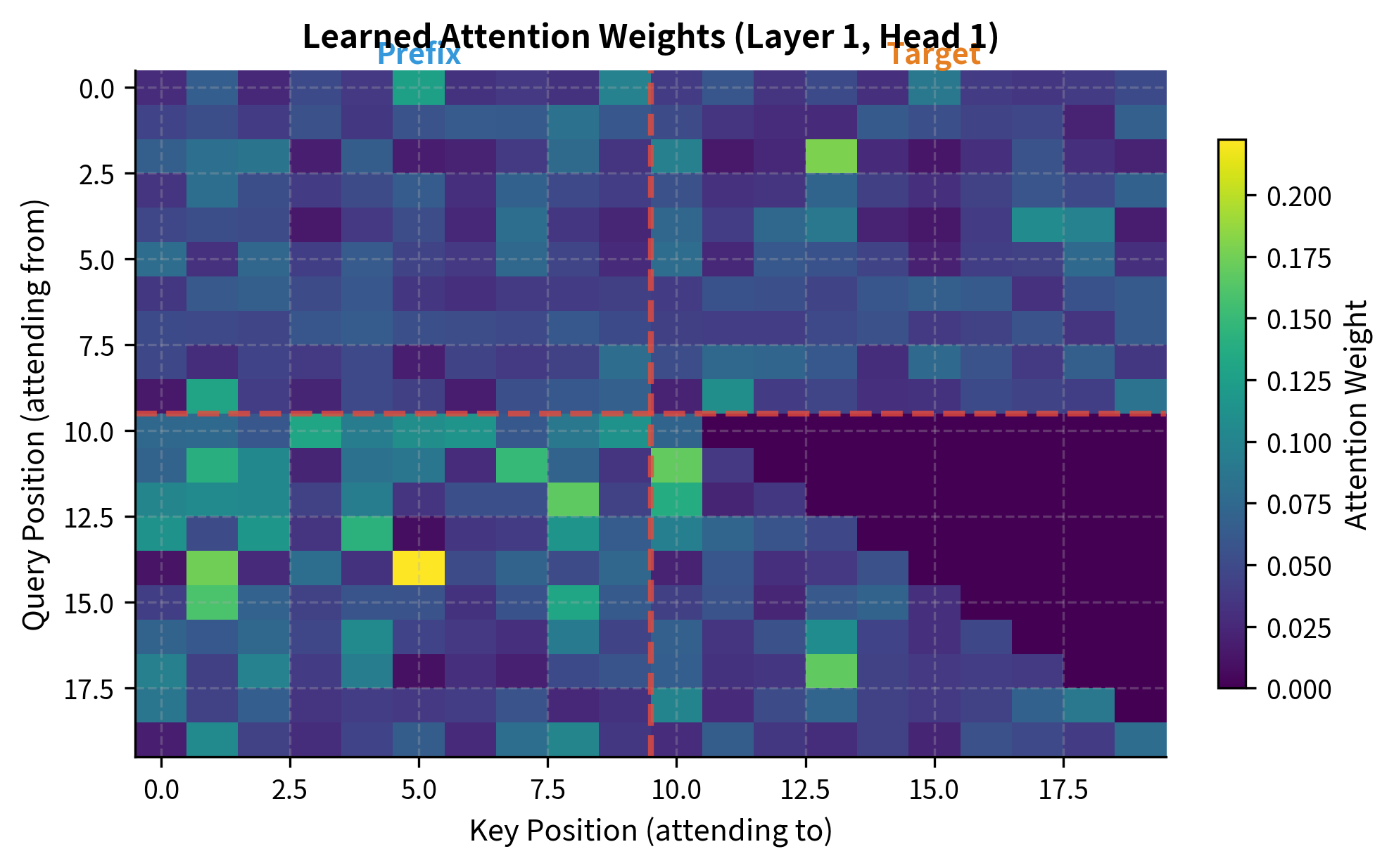

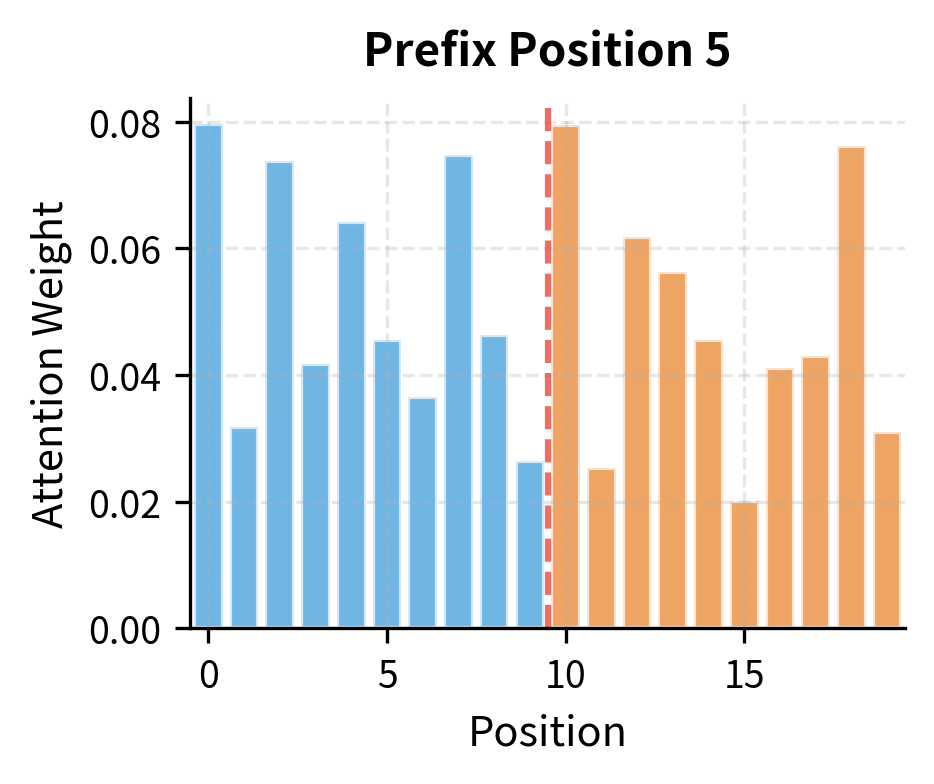

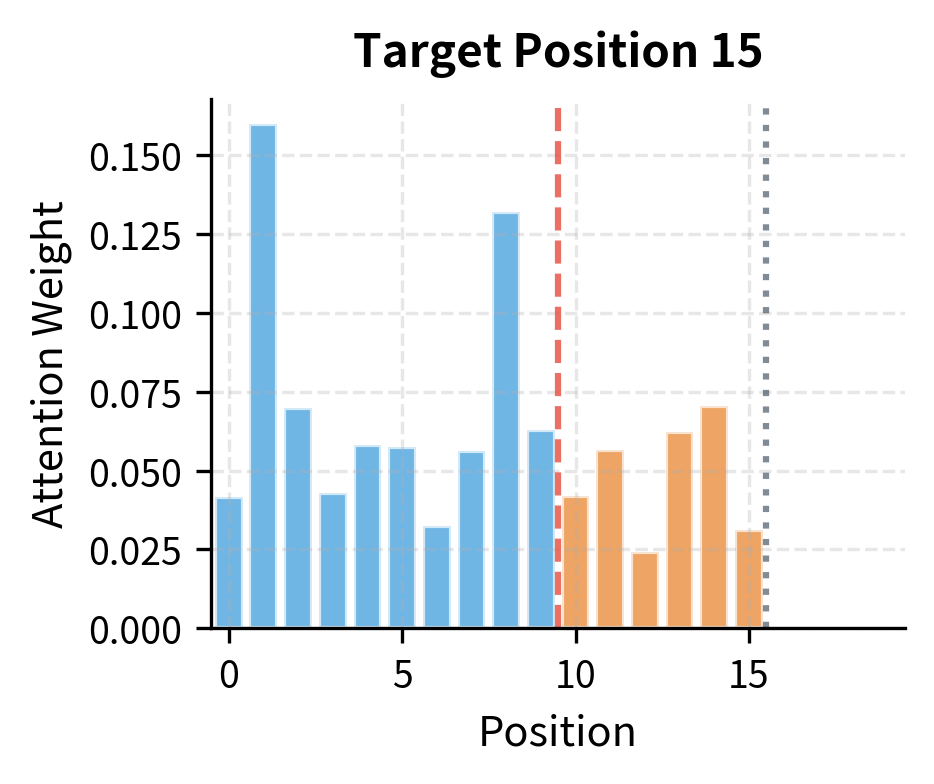

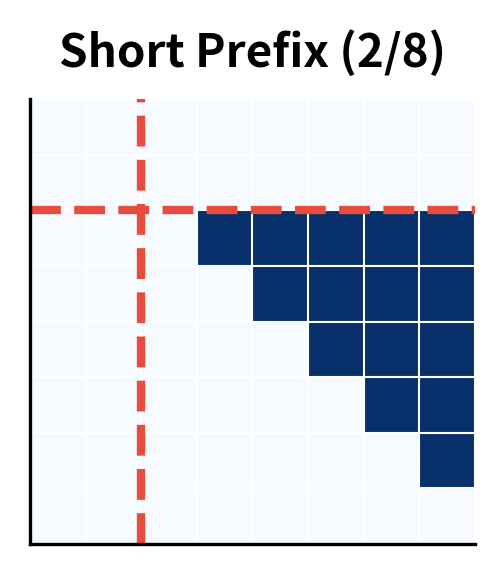

To see the prefix LM attention pattern in action, we can extract and visualize the attention weights from our trained model. This reveals how the model actually distributes attention across prefix and target positions:

The attention heatmap reveals the prefix LM pattern in action. Notice how positions in the prefix region (left of the red dashed line) distribute attention broadly across all prefix positions, indicating bidirectional processing. Target positions (right of the line) show the characteristic causal pattern: each attends heavily to the prefix and to preceding target positions, but attention to future positions is blocked.

Comparing these attention distributions highlights the fundamental difference between prefix and target positions. The prefix position distributes attention across all accessible positions (itself and all others in the sequence), while the target position can only attend to the prefix and prior target positions, with future positions completely masked out.

UniLM-Style Unified Training

A powerful extension of prefix LM is training a single model on multiple objectives simultaneously. UniLM (Unified Language Model) pioneered this approach, training on three objectives in each batch:

The unified training produces a model capable of all three modes. At inference time, you select the appropriate attention pattern for your task. This flexibility makes UniLM-style models particularly versatile.

Bidirectional mode allows all 36 position pairs to attend to each other. Unidirectional mode blocks 15 positions (the upper triangle), allowing only 21 attend pairs. Prefix LM falls between these extremes: with a prefix of 3 tokens, it allows more attention than causal but less than bidirectional, as the last 3 positions still use causal masking.

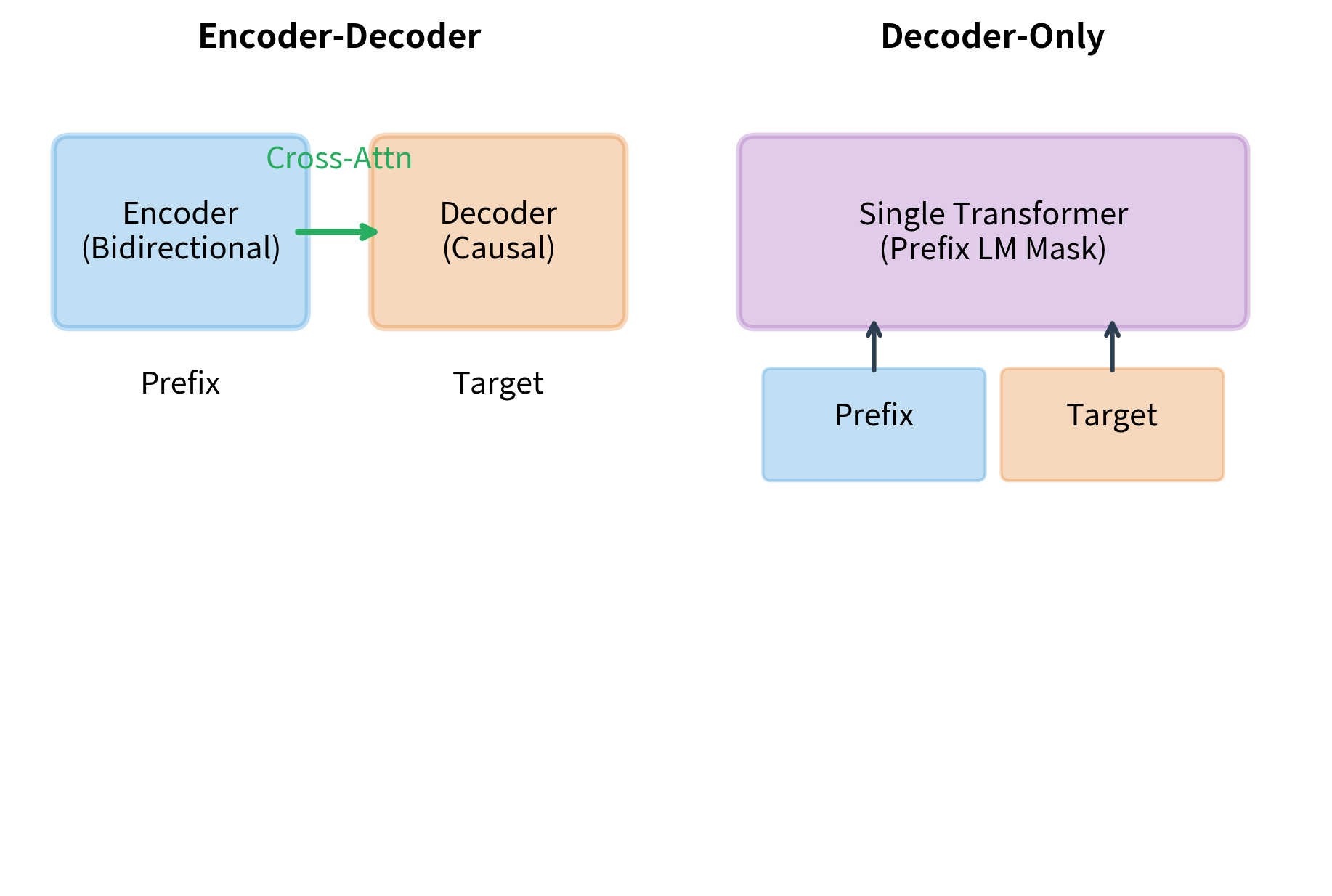

Encoder-Decoder vs Decoder-Only Prefix LM

Prefix LM can be implemented in two architectural styles, each with distinct trade-offs.

Encoder-decoder models like T5 process the prefix through a bidirectional encoder, then pass encoded representations to a causal decoder that generates the target. The encoder and decoder are separate modules with cross-attention connecting them.

Decoder-only models like GPT use a single transformer stack with the prefix LM attention mask. The same weights process both prefix and target, with the attention mask controlling information flow.

The choice between architectures depends on the application. Encoder-decoder models can process very long prefixes efficiently since encoder states are computed once and reused. Decoder-only models are simpler to implement and often perform comparably for shorter contexts.

Prefix Length and Its Effects

The prefix length significantly affects model behavior. Longer prefixes provide more context but leave less room for the target. The split point can be fixed or varied during training.

Random prefix lengths during training, as we used earlier, help the model generalize across different split points. This is especially useful for tasks where the natural prefix-target boundary varies.

Use Cases for Prefix LM

Prefix LM naturally fits many sequence-to-sequence tasks where the input is fully known before generation begins:

- Machine Translation: The source sentence is the prefix, the target sentence is the target. The full source can be processed bidirectionally, enabling the model to understand the complete meaning before generating the translation.

- Summarization: Long documents form the prefix, and the concise summary is the target. Bidirectional processing of the document captures its full structure before generating a condensed version.

- Question Answering: The context passage and question together form the prefix. The answer is generated as the target. The model can cross-reference question words with passage content bidirectionally.

- Code Generation: Comments or specifications serve as the prefix, and the code implementation is the target. Understanding the full specification before generating code produces more coherent implementations.

- Dialogue: Conversation history is the prefix, and the next response is the target. The model attends to the full conversation before generating a contextually appropriate reply.

Limitations and Impact

Prefix language modeling represents a principled middle ground between understanding-focused MLM and generation-focused CLM, but it introduces its own challenges.

The primary limitation is the need to define a split point. Natural language doesn't always divide cleanly into "context" and "continuation." In conversation, the boundary between prior turns and the current response is clear. In creative writing, there's no natural split. Training with random splits helps, but the model may not optimally handle all split configurations at inference time.

Computational considerations also matter. Encoder-decoder implementations can cache prefix encodings efficiently, but decoder-only implementations must recompute prefix attention as the sequence grows. For long prefixes and targets, this quadratic cost becomes significant.

Despite these challenges, prefix LM has shaped how we design language models. T5's text-to-text framework builds on prefix LM ideas, treating every NLP task as conditioned generation. UL2 (Unified Language Learner) combines prefix LM with other objectives for improved general capability. The insight that different parts of a sequence warrant different attention patterns has become a core principle in modern architecture design.

The most significant impact may be conceptual: prefix LM demonstrated that a single architecture can handle both understanding and generation by simply adjusting the attention mask. This unification has driven the field toward flexible, multi-purpose models that adapt their behavior based on how they're queried, rather than requiring separate models for separate tasks.

Key Parameters

When training prefix language models, several parameters significantly affect performance:

- prefix_len: The number of tokens in the bidirectional prefix region. Determines the split point between context and generation. Longer prefixes provide richer context but leave less room for target generation.

- min_prefix_frac / max_prefix_frac: When using random prefix lengths during training (0.3 to 0.7 in our example), these control the range of possible split points. Wider ranges help the model generalize across different prefix-target ratios.

- d_model: The hidden dimension of the transformer. Larger values (64, 128, 256) increase model capacity for capturing complex patterns in both prefix and target.

- n_heads: Number of attention heads. More heads allow the model to attend to different aspects of the prefix context simultaneously.

- n_layers: Depth of the transformer stack. Deeper models can learn more complex relationships between prefix context and target generation.

- learning_rate: Typically 1e-4 to 1e-3 for prefix LM training. The bidirectional prefix may allow slightly higher learning rates than pure causal LM since gradients flow more freely.

- temperature: Controls randomness during generation (0.7 to 1.0 typical). Lower values make generation more deterministic, higher values increase diversity.

Summary

Prefix language modeling combines bidirectional context encoding with causal generation, offering a powerful middle ground between MLM and CLM. This chapter covered the key concepts:

- The prefix LM split divides sequences into a bidirectional prefix and a causal target, enabling rich context understanding while maintaining generation capability

- The attention pattern forms an L-shape, with full attention in the prefix region and causal masking in the target region

- Loss computation focuses only on target positions, training the model specifically for conditioned generation

- UniLM-style training combines multiple objectives (bidirectional, causal, prefix) in a single model, creating versatile architectures

- Architectural choices include encoder-decoder and decoder-only implementations, each with distinct trade-offs for different use cases

- Applications span translation, summarization, QA, and dialogue, where the prefix-target structure matches the task naturally

The next chapter explores replaced token detection, an alternative to masking that uses a discriminative objective for more efficient pretraining.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about prefix language modeling.

Comments