Master attention masking techniques including padding masks, causal masks, and sparse patterns. Learn how masking enables autoregressive generation and efficient batch processing.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Attention Masking

Self-attention computes pairwise interactions between all positions in a sequence. But sometimes we need to block certain interactions. A model generating text should not peek at future tokens. Sequences padded to equal length should not attend to padding tokens. These constraints are implemented through attention masking, a technique that selectively prevents certain positions from influencing others.

Masking modifies the attention computation by adding large negative values to specific positions before the softmax. Recall that attention weights are computed as:

where:

- : the attention weight from query position to key position

- : the raw attention score between positions and

- : the sequence length

When we add a large negative value (like ) to a score , the exponential becomes vanishingly small, driving to near-zero. These masked positions effectively disappear from the weighted sum. This simple mechanism enables causal language modeling, efficient batch processing, and custom attention patterns.

Why Masking Matters

Consider training a language model to predict the next word. Given "The cat sat on the," the model should predict "mat" based only on the preceding words. But standard self-attention allows every position to see every other position, including future tokens. Without intervention, the model could cheat by looking ahead.

An attention mask is a matrix of values that modifies attention scores before softmax. Positions marked for masking receive large negative values, causing the softmax to assign them near-zero weights. This effectively prevents the query from attending to those positions.

Masking solves this by blocking attention to future positions during training. The model learns to predict each token using only past context, matching the autoregressive setup it will encounter during generation.

Padding presents a similar challenge. When batching sequences of different lengths, we pad shorter sequences to match the longest. But these padding tokens carry no meaning. Allowing real tokens to attend to padding would corrupt their representations with noise. Masking removes padding from the attention computation entirely.

Padding Masks

Real-world text comes in varying lengths. "Hello" has one token while "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" has nine. To process multiple sequences efficiently in a batch, we pad shorter sequences to a common length using a special padding token.

Padding ensures uniform tensor shapes, but it introduces tokens that should be invisible to the attention mechanism. A padding mask marks which positions contain real tokens versus padding.

The padding mask is a boolean array where True marks real tokens and False marks padding. To apply this mask to attention scores, we need to convert it into an additive mask.

Converting to Attention Mask

We have a boolean padding mask, but attention needs numerical scores. How do we bridge this gap? The answer lies in understanding how softmax behaves with extreme values.

Softmax converts a vector of arbitrary real numbers into a probability distribution. The key insight is that softmax is sensitive to relative differences between values, not their absolute magnitudes. When computing softmax, each score is exponentiated, then divided by the sum of all exponentials:

If one score is extremely negative while others are moderate, its exponential becomes vanishingly small. To illustrate, consider applying softmax to a vector with one large negative value:

The third element receives essentially zero weight. Why? Because is astronomically small compared to and . In fact, is so close to zero that floating-point arithmetic rounds it to exactly zero.

This gives us our masking strategy: add a large negative value to positions we want to block. We typically use rather than true infinity to avoid numerical edge cases, though both work in practice.

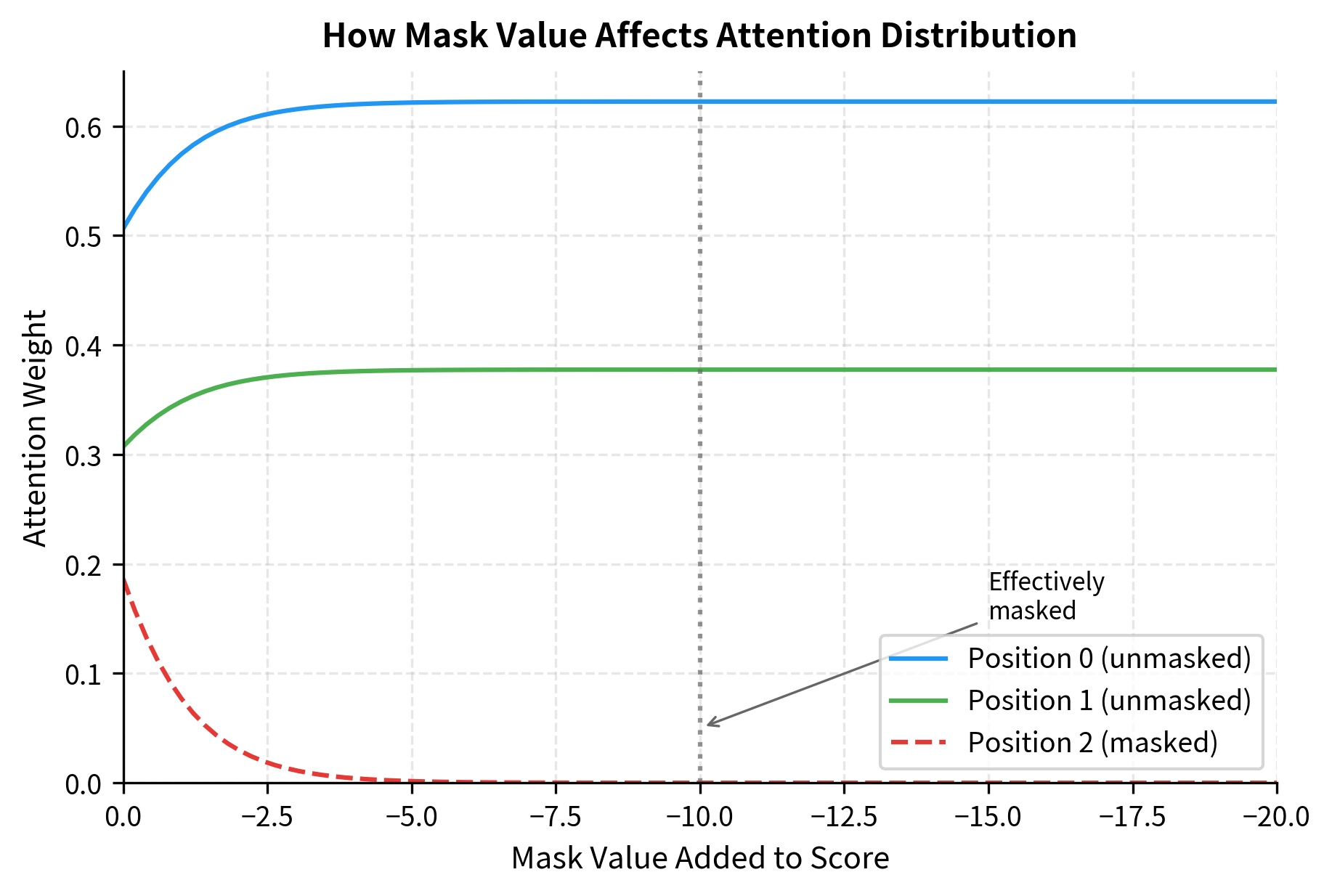

The plot demonstrates why we use large negative values like . Even a mask value of reduces the masked position's weight to near zero, while makes it essentially invisible. The unmasked positions automatically absorb the redistributed attention.

The attention mask has shape (batch, seq_len, seq_len). For sequence 0, the last column contains large negative values because position 3 is padding. Every query position will receive near-zero attention weight for position 3 after softmax.

Visualizing Padding Mask Effects

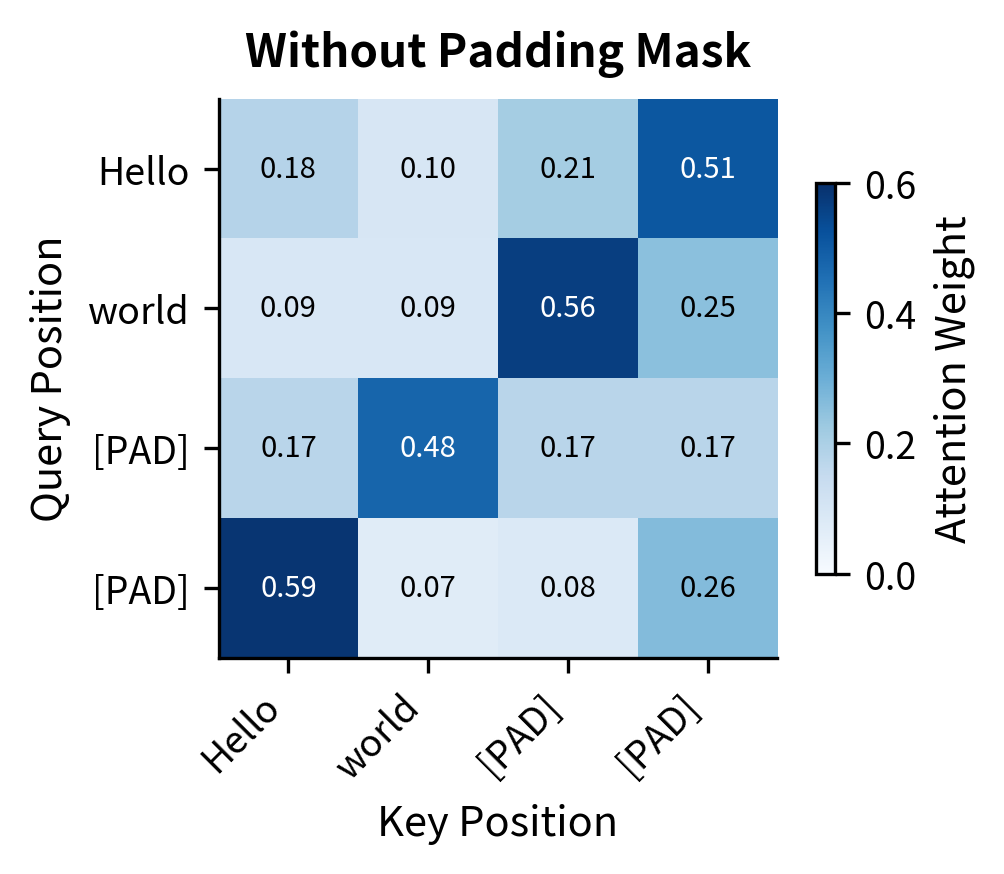

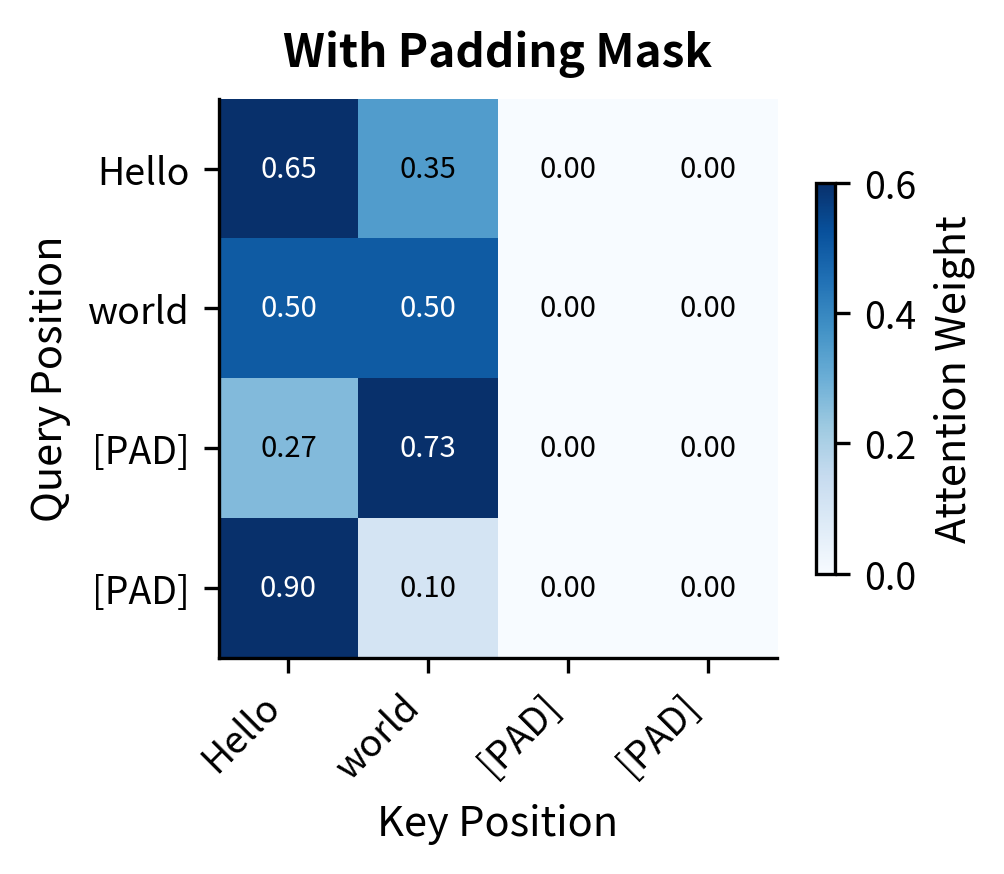

Let's see how padding masks affect attention weights. We'll create random attention scores and compare the distributions with and without masking.

The contrast is stark. Without masking, attention flows to all positions including padding. The padding tokens absorb 10-30% of the attention weight at each query position. With the mask applied, padding positions receive exactly 0.00 weight, and the remaining attention redistributes entirely to real tokens. This ensures padding never contaminates token representations.

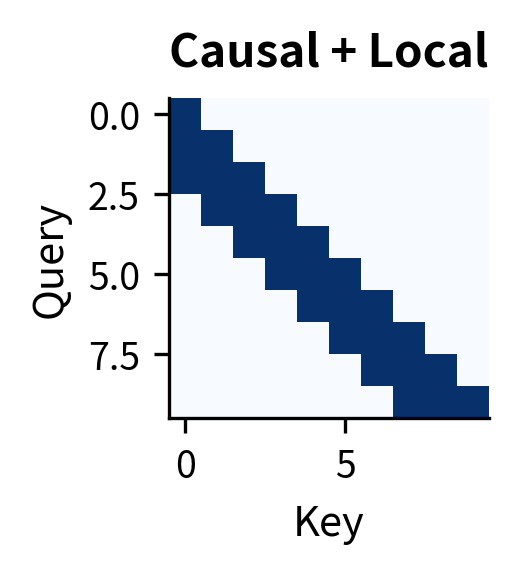

Causal Masks

Causal masking, also called look-ahead masking, prevents positions from attending to future positions. This is essential for autoregressive language models that generate text one token at a time.

During training, we process entire sequences in parallel for efficiency. But the model must learn to predict each position using only past context. Causal masking enforces this constraint: position can only attend to positions , where is the current position index (0-indexed).

Causal attention restricts each position to attend only to itself and previous positions. This creates a left-to-right information flow where future tokens cannot influence past representations.

The Causal Mask Formula

How do we formalize "only attend to past positions"? We need a mask that blocks any attention where the key position comes after the query position. Mathematically, the causal mask is defined as:

where:

- : the query position (row index), representing the token that is "asking"

- : the key position (column index), representing the token being attended to

- : the mask value added to the attention score at position

The condition means "key position is at or before query position." When this holds, we add 0 (no masking). When , the key is in the future relative to the query, so we add to block attention.

This creates a lower triangular pattern of zeros and an upper triangular pattern of infinities:

Position 0 can only attend to itself (only position 0 has value 0). Position 1 can attend to positions 0 and 1. Position 4 can attend to all positions. The upper triangle is filled with large negative values, blocking all look-ahead.

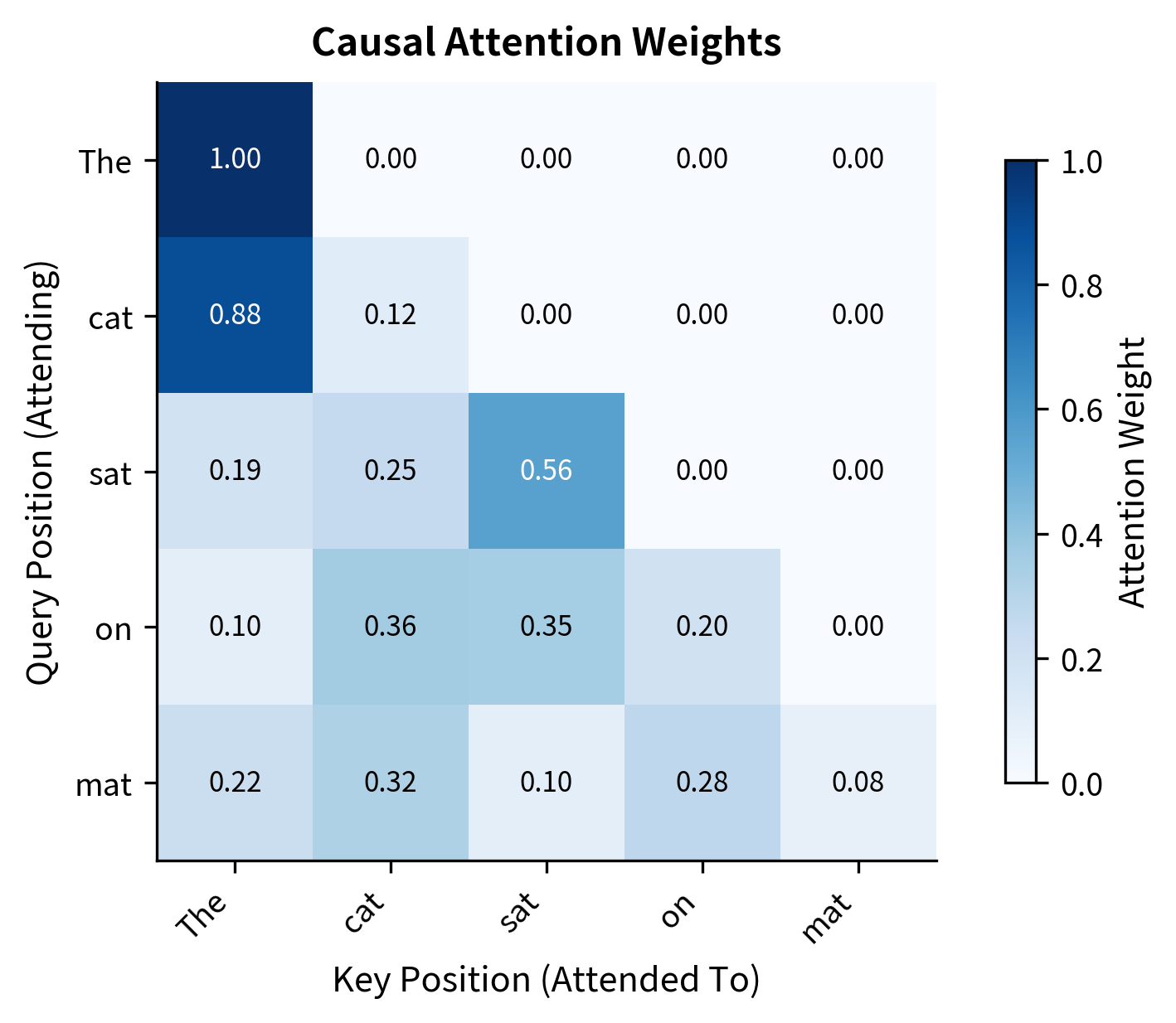

Visualizing Causal Attention

Let's trace through how causal masking affects attention during sequence processing.

The triangular structure is clear. "The" at position 0 attends entirely to itself (weight 1.00) because it has no past context. "cat" can attend to "The" or itself. By position 4, "mat" distributes attention across all five positions based on learned relevance patterns.

This structure ensures that when training on a sequence like "The cat sat on mat," each position learns to predict the next token using only information from positions to its left.

Why Causal Masking Enables Parallel Training

Without causal masking, training autoregressive models would be painfully slow. We would need to generate one token at a time, feeding each output back as input for the next. With causal masking, we can process the entire training sequence in parallel.

Each row of the attention matrix corresponds to one prediction task. Row 0 uses context , row 1 uses context , and so on. The causal mask automatically provides the correct context for each prediction position without needing separate forward passes.

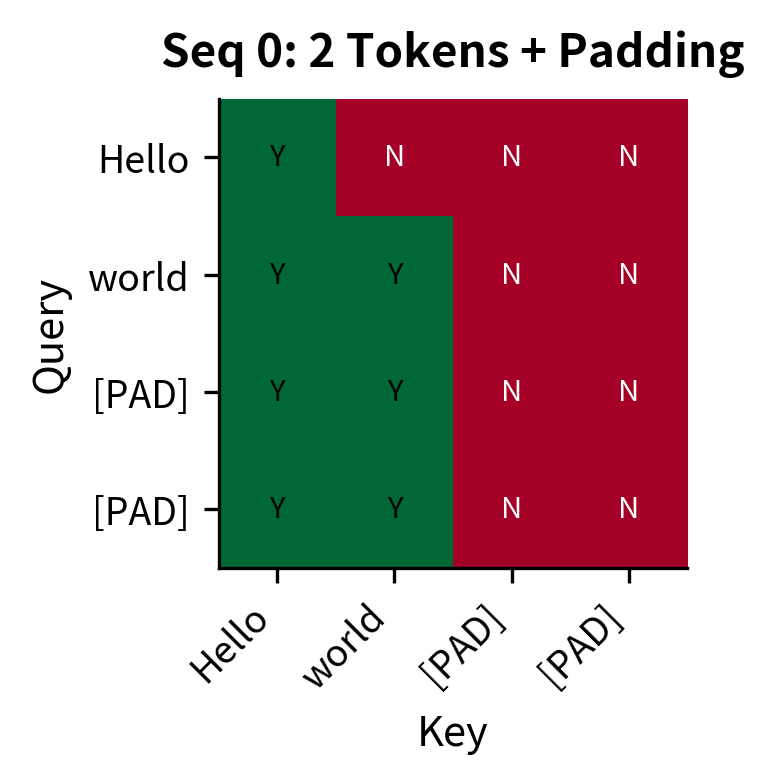

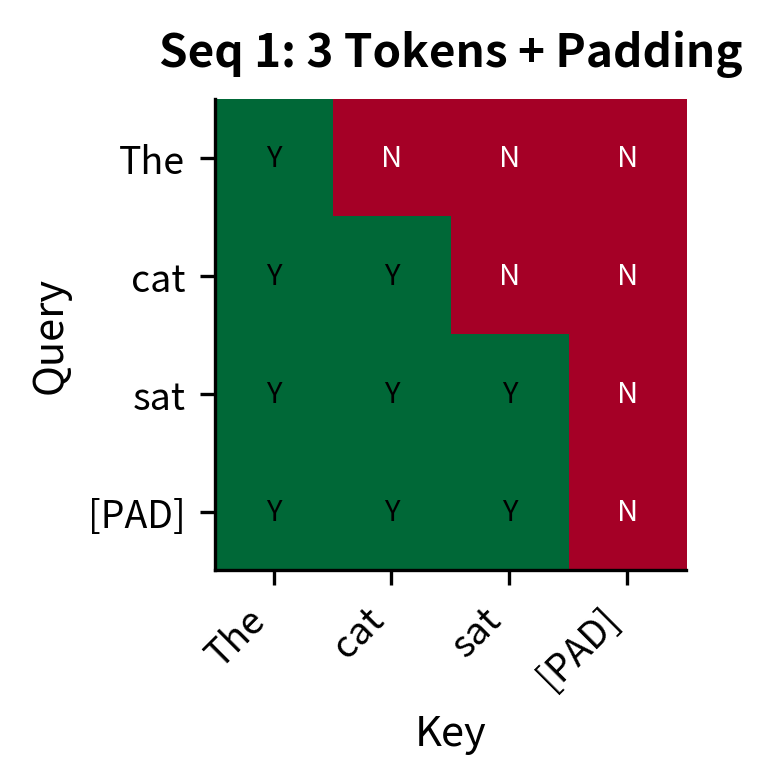

Combining Multiple Masks

Real models often need both padding and causal masks simultaneously. A decoder processing batched sequences must handle variable lengths (requiring padding masks) while maintaining autoregressive constraints (requiring causal masks).

The solution is straightforward: combine masks by addition. If we have a causal mask and a padding mask , the combined mask is:

Since both masks use for blocked positions and 0 for allowed positions, the sum gives wherever either mask blocks attention. A position is only allowed (value 0) when both masks allow it.

For sequence 0 with 2 real tokens, the combined mask blocks:

- Upper triangle (causal constraint)

- Columns 2 and 3 (padding positions)

The resulting mask allows each position to attend only to past, non-padding positions.

The green cells marked "Y" show where attention is allowed. For sequence 0, only the 2x2 lower-left block is active. For sequence 1, the 3x3 lower-left block allows attention. Both patterns combine causal and padding constraints in a single mask.

Mask Shapes and Broadcasting

Attention masks can have different shapes depending on the use case. Understanding these shapes and how they broadcast is crucial for correct implementation.

The attention score matrix has shape (batch, num_heads, seq_len, seq_len) in a full transformer with multi-head attention. Masks can be:

- Full shape

(batch, num_heads, seq_len, seq_len): Fully specified mask for every batch item and head - Per-batch

(batch, 1, seq_len, seq_len): Same mask across all heads, different per batch item - Per-batch compact

(batch, 1, 1, seq_len): Key-only masking (like padding masks) - Global

(1, 1, seq_len, seq_len): Same mask for entire batch (like causal masks)

NumPy and PyTorch broadcast smaller masks to match the score tensor shape.

Broadcasting rules make mask combination elegant. The causal mask (1, 1, 8, 8) applies identically to all batch items and heads. The padding mask (2, 1, 1, 8) applies per batch item across all heads, masking keys based on which positions are padding. The final result (2, 4, 8, 8) has the correct combined mask for each batch item and attention head.

Memory-Efficient Masking

For very long sequences, storing full (seq_len, seq_len) masks becomes expensive. A 10,000-token sequence requires 100 million entries per mask. Several strategies reduce this cost.

Lazy mask generation: Instead of precomputing the full mask, generate it during the attention computation.

A 1000-token sequence requires 4 MB just for the mask tensor. The lazy approach avoids this allocation by setting mask values directly on the score matrix during computation.

Boolean masks: Store masks as boolean arrays (1 byte per element) rather than float32 (4 bytes), converting to float only when needed.

For sequences of length 1000, boolean masks use 75% less memory. This adds up when processing large batches or very long documents.

Efficient Masking Implementation

With our understanding of padding and causal masks in place, we can now build a complete masked attention function. The key insight is that masking integrates seamlessly into the standard attention formula through a single addition operation.

The Masked Attention Formula

Recall that standard scaled dot-product attention computes:

To add masking, we simply insert the mask matrix before the softmax:

where:

- : the query matrix of shape , representing what each position is "looking for"

- : the key matrix of shape , representing what each position "offers"

- : the value matrix of shape , containing the information to aggregate

- : the mask matrix of shape , with 0 for allowed and for blocked positions

- : the dimension of queries and keys, used for scaling to prevent vanishing gradients

- : the sequence length

The formula unfolds in three steps:

-

Compute raw scores: produces an matrix where entry measures the similarity between query and key .

-

Scale and mask: Divide by to stabilize gradients, then add the mask . Masked positions receive , which the softmax will convert to near-zero weights.

-

Normalize and aggregate: Softmax converts scores to weights summing to 1 (per row), then these weights select and combine values from .

This formulation is elegant because the mask doesn't change the computational structure. We still compute all pairwise scores, but the masking happens through simple addition before softmax. The exponential function in softmax then "erases" the masked positions.

Implementing Masked Attention

Let's translate the formula into code. The implementation follows the three-step structure exactly:

Notice how the mask application is just a single line: scores = scores + mask. This simplicity is intentional. The mask contains 0 for allowed positions (no effect on scores) and large negative values for blocked positions (which softmax converts to near-zero weights). No branching, no special cases, just addition.

Testing the Implementation

Let's verify that our implementation correctly handles both padding and causal masks:

The attention weight matrix confirms that both masks work together correctly. Looking at the output for batch 1 (which has 4 real tokens and 2 padding tokens):

-

Columns 4 and 5 are nearly zero: The padding mask successfully blocks attention to padding positions. No real token wastes attention on meaningless padding.

-

Upper triangle is nearly zero: The causal mask blocks attention to future positions. Position 0 cannot see positions 1-5, position 1 cannot see positions 2-5, and so on.

-

Lower-left region has non-zero weights: The intersection of "past positions" and "real tokens" receives all the attention. These are exactly the positions each query should attend to.

The combined mask creates a triangular pattern truncated by the padding boundary. This is precisely what a causal language model needs when processing variable-length batched sequences.

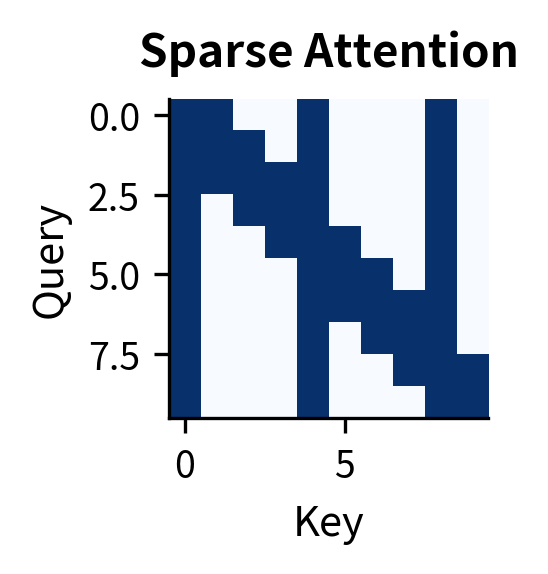

Custom Attention Patterns

Beyond standard padding and causal masks, researchers have explored various attention patterns for efficiency and modeling goals.

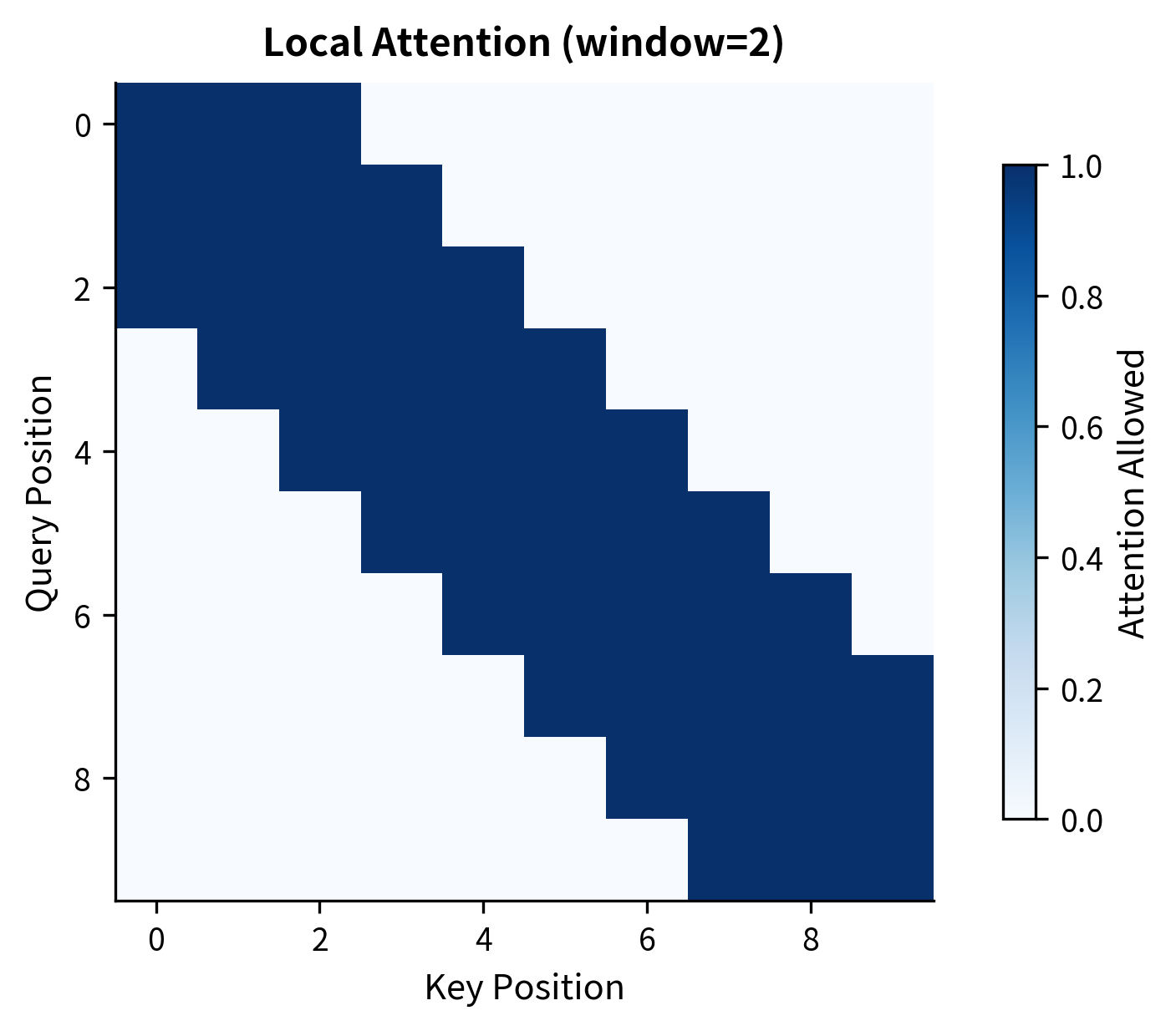

Local Attention

Restrict attention to a fixed window around each position. This reduces complexity from to , where:

- : the sequence length (total number of tokens)

- : the window size (number of positions each token can attend to)

Local attention is used in models like Longformer to handle very long sequences. The window captures local context efficiently, and special "global" tokens can still attend to all positions for long-range information.

Strided Attention

Attend to every -th position, spreading attention across the sequence with fixed intervals. Here, is the stride parameter that controls how far apart attended positions are.

Combined Patterns

Real efficient attention mechanisms often combine multiple patterns. Sparse Transformer uses local + strided attention to cover both nearby and distant positions.

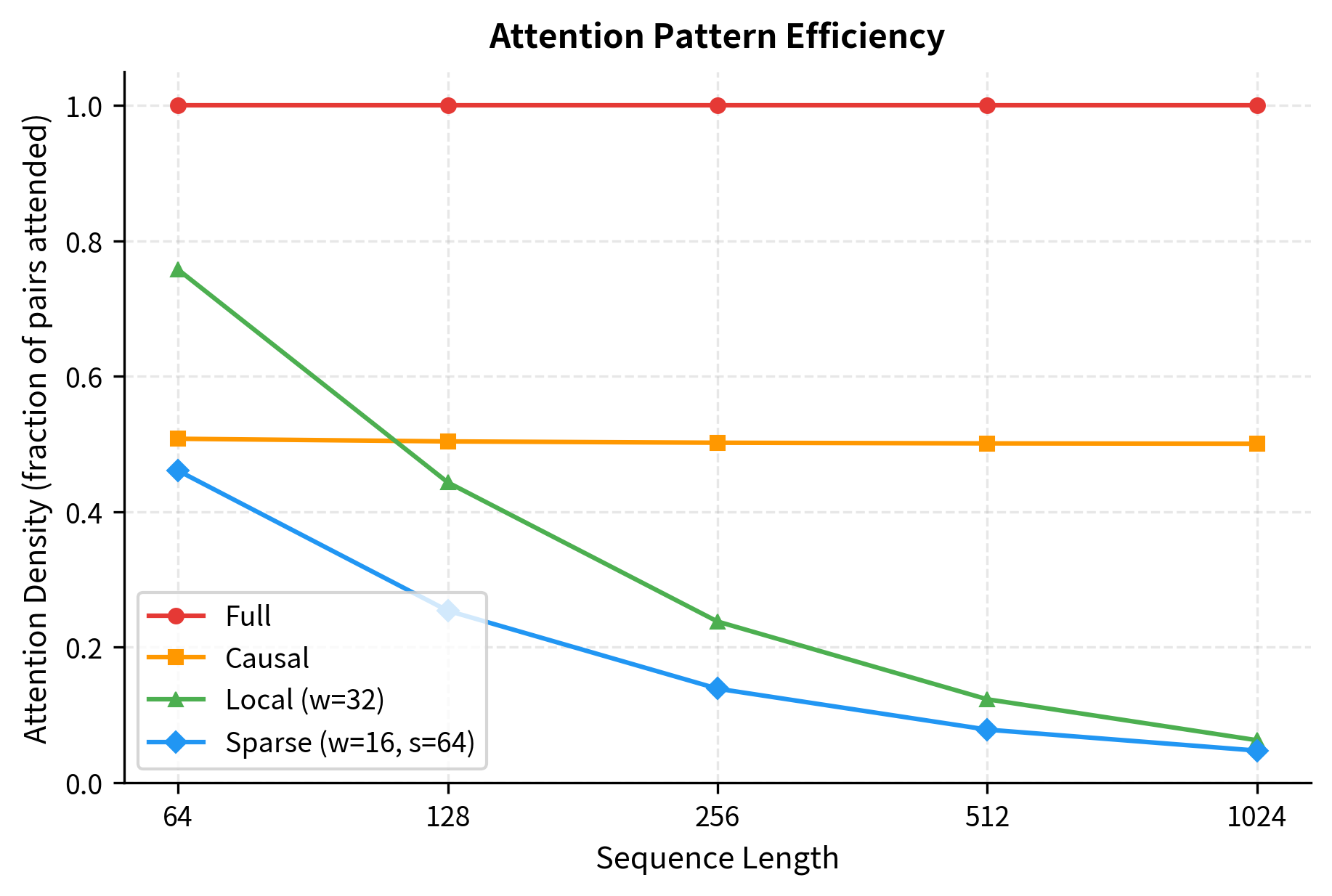

Each pattern represents a different trade-off. Full attention has maximum expressiveness but cost, where is the sequence length. Sparse patterns reduce complexity at the cost of some long-range interactions. The choice depends on sequence length, available compute, and task requirements.

The efficiency gains are dramatic. Full attention always uses 100% of possible pairs. Causal attention uses ~50% (the lower triangle). But local and sparse patterns become increasingly efficient as sequences grow longer: at 1024 tokens, local attention with window 32 uses only ~6% of pairs, and sparse patterns even less. This is why efficient attention variants are essential for processing long documents.

Limitations and Impact

Attention masking is essential infrastructure for modern transformers, but it introduces its own complexities and constraints.

The most significant limitation is computational overhead. While masking itself is cheap (just addition before softmax), it doesn't reduce the fundamental cost of computing all pairwise attention scores, where is the sequence length. Even with half the positions masked, we still compute the full score matrix. Truly sparse attention requires specialized implementations that skip masked computations entirely, which is harder to optimize on GPUs that prefer dense, regular operations. Libraries like FlashAttention address this by fusing the entire attention computation, mask included, into a single kernel.

Masking also constrains what the model can learn. Causal masking prevents bidirectional context, which is suboptimal for tasks like fill-in-the-blank or sentence classification. This is why BERT uses bidirectional attention (no causal mask) while GPT uses causal attention. The mask choice becomes an architectural decision that shapes what the model can and cannot do.

Despite these limitations, masking unlocked critical capabilities. Causal masking enabled efficient parallel training of autoregressive models, which would otherwise require sequential generation during training. Padding masks allowed practical batching of variable-length sequences. Custom patterns like local and strided attention extended transformers to sequence lengths previously impossible. Without masking, the transformer architecture would be far less practical and flexible.

Key Parameters

When implementing attention masking, several parameters control the mask behavior:

-

mask_value: The large negative value used for masked positions (typically or

-float('inf')). Using rather than true infinity avoids numerical issues with some operations while still producing near-zero attention weights after softmax. -

window_size (local attention): Controls how many positions on each side a token can attend to. Smaller windows reduce computation but may miss important long-range dependencies. Common values range from 128 to 512 tokens.

-

stride (strided attention): Determines the spacing between attended positions in sparse patterns. A stride of means attending to every -th position, reducing complexity while maintaining some global connectivity.

-

pad_token_id: The token ID used for padding in tokenized sequences. This must match the padding token used during tokenization to correctly identify positions to mask.

Summary

Attention masking controls which positions can attend to which others, enabling autoregressive generation and efficient batch processing.

The key concepts from this chapter:

- Additive masking: Adding large negative values before softmax drives attention weights to near-zero, effectively blocking those positions

- Padding masks: Prevent attention to padding tokens when batching sequences of different lengths. Real tokens should not be influenced by meaningless padding values

- Causal masks: Block attention to future positions, enforcing left-to-right information flow for autoregressive language models. This enables parallel training while maintaining proper context constraints

- Mask combination: Multiple masks combine by addition. Any position blocked by any mask receives near-zero attention

- Broadcasting: Masks can have shapes like

(1, 1, seq_len, seq_len)for global patterns or(batch, 1, 1, seq_len)for per-sequence patterns, with broadcasting handling dimension expansion - Custom patterns: Local, strided, and sparse attention patterns reduce complexity for long sequences by limiting which positions can interact

In the next chapter, we'll explore multi-head attention, which runs multiple attention operations in parallel with different learned projections. This allows the model to attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about attention masking.

Comments