Learn how attention mechanisms solve the information bottleneck in encoder-decoder models through soft lookup, alignment scores, and dynamic context vectors.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Attention Intuition

In the encoder-decoder framework, we compress an entire input sequence into a single fixed-length vector. This works reasonably well for short sequences, but as inputs grow longer, that single vector becomes an information bottleneck. How can we expect one vector to faithfully represent a 50-word sentence, let alone an entire paragraph?

Attention solves this by allowing the decoder to look back at all encoder states and decide which parts of the input are most relevant at each decoding step. Instead of relying on a compressed summary, the model learns to focus on different parts of the input as it generates each output token. This idea improved sequence-to-sequence models and became the foundation for the transformer architecture used in modern NLP.

Attention as Soft Lookup

Think of attention as a soft, differentiable dictionary lookup. In a traditional dictionary, you provide a key and get back exactly one value. Attention works similarly, but instead of retrieving a single value, it retrieves a weighted combination of all values based on how well each key matches your query.

Consider a translation task where you're generating the French word for "cat" from an English sentence. Rather than searching through the entire compressed representation, attention lets the decoder ask: "Which parts of the input are most relevant right now?" The answer comes as a probability distribution over all input positions.

Hard attention selects exactly one input position (like a traditional lookup), while soft attention computes a weighted average over all positions. Soft attention is differentiable and can be trained with backpropagation, making it the standard choice for neural networks.

The mechanics involve three components: a query (what we're looking for), keys (what we're comparing against), and values (what we retrieve). In the context of encoder-decoder models:

- The query comes from the decoder's current state

- The keys are the encoder's hidden states

- The values are also the encoder's hidden states (often the same as keys)

The attention mechanism computes similarity scores between the query and all keys, normalizes these scores into a probability distribution, and then returns a weighted sum of the values. This weighted sum is the context vector that the decoder uses alongside its own state to generate the next token.

The Mathematics of Attention

Now that we have the intuition, let's translate it into precise mathematics. The goal is to build a mechanism that answers a simple question at each decoding step: "Which parts of the input should I focus on right now?"

Imagine you're the decoder, trying to generate the next word in a translation. You have your current state , which encodes what you've generated so far and what you're trying to produce next. Meanwhile, the encoder has processed the entire input sentence and produced a sequence of hidden states , one for each of the input words. Each encoder state captures the meaning of word in context.

The challenge is clear: you need to selectively combine information from all these encoder states, giving more weight to positions that are relevant to your current generation task. Attention solves this in three steps.

Step 1: Measuring Relevance with Alignment Scores

The first question attention must answer is: "How relevant is each input position to what I'm currently generating?" We need a way to compare the decoder's current state with each encoder state and produce a relevance score.

This comparison happens through a scoring function:

where:

- : the alignment score, a single number indicating how relevant encoder position is when generating at decoder position

- : the decoder's hidden state at step , encoding the generation context

- : the encoder's hidden state at position , encoding information about input word

- : any function that takes two vectors and returns a scalar measuring their compatibility

Think of this as the decoder asking each encoder position: "How useful are you for what I'm trying to do right now?" The score function quantifies the answer. A high score means "very useful," while a low or negative score means "not relevant."

What should this scoring function look like? The simplest choice is the dot product, , which measures how aligned the two vectors are in the embedding space. Vectors pointing in similar directions yield high scores; orthogonal vectors yield zero. We'll explore more sophisticated scoring functions in subsequent chapters, but the core idea remains: compare the query (decoder state) against each key (encoder state) to measure relevance.

Step 2: Converting Scores to a Probability Distribution

Raw alignment scores present a problem: they can be any real number, positive or negative, large or small. We need to convert them into something more interpretable and usable, specifically, a probability distribution over input positions.

The softmax function accomplishes this transformation:

where:

- : the attention weight for position , now guaranteed to be between 0 and 1

- : the exponential function applied to the alignment score, converting any real number to a positive value

- : the sum of all exponentiated scores, serving as a normalizing constant

Why softmax? It has exactly the properties we need. First, the exponential function maps any real number to a positive value, ensuring all weights are non-negative. Second, dividing by the sum of all exponentials guarantees that . The result is a valid probability distribution.

Softmax also has a useful amplification property. If one score is much larger than the others, its corresponding weight will dominate. For example, if and all other scores are near 0, then will be close to 1 while the other weights approach 0. This allows the model to focus sharply on a single position when appropriate, or spread attention across multiple positions when the relevance is more evenly distributed.

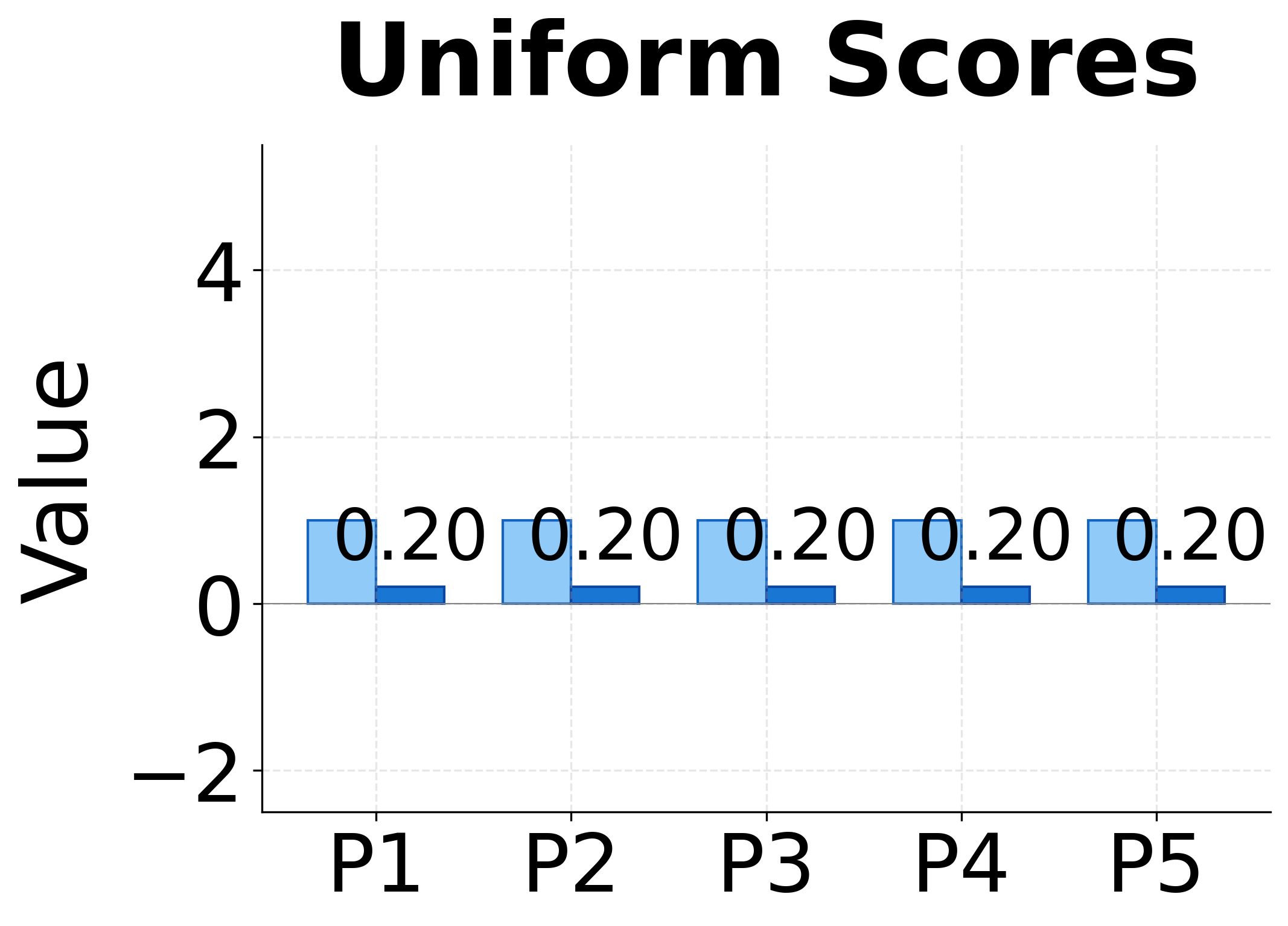

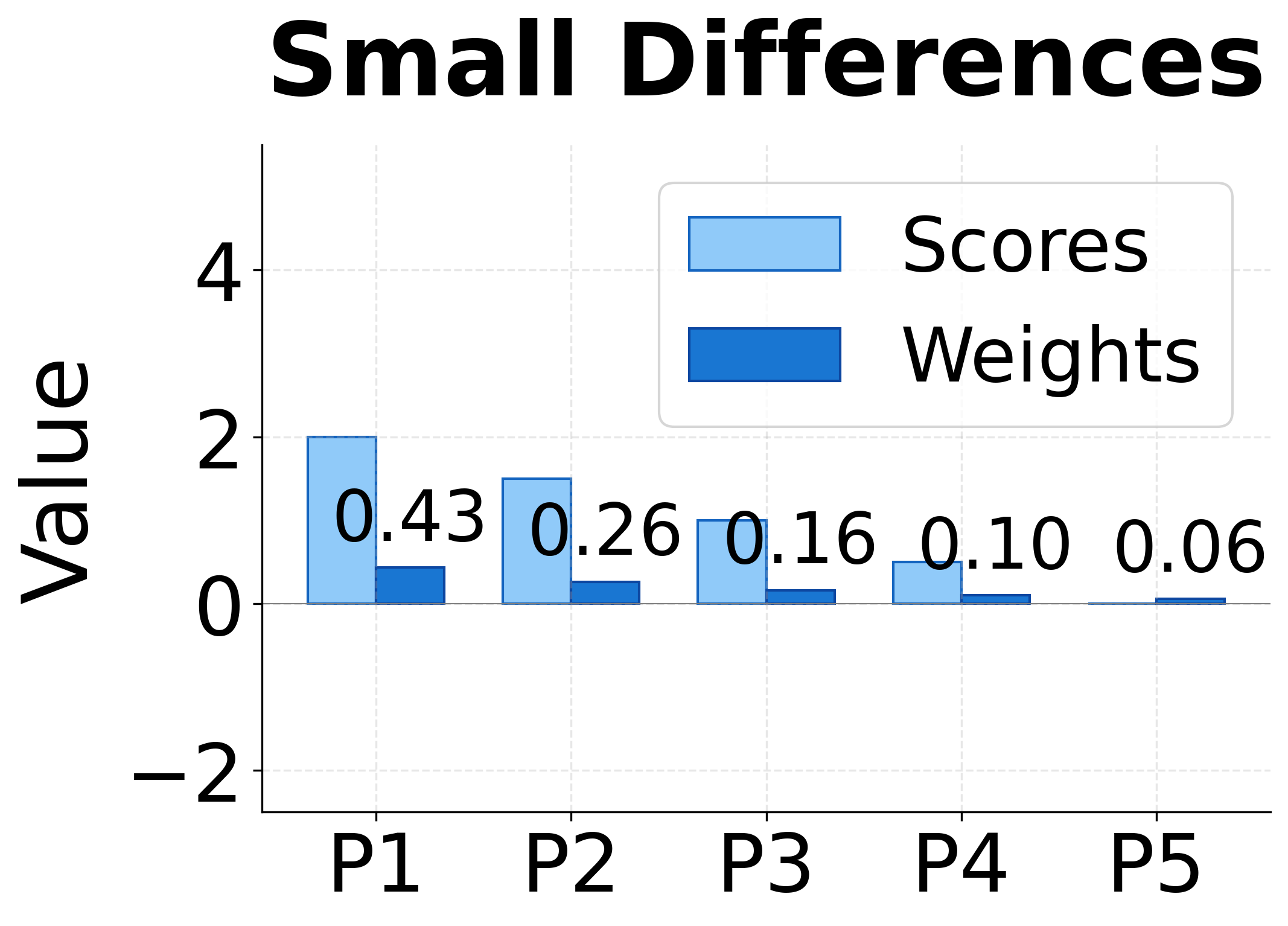

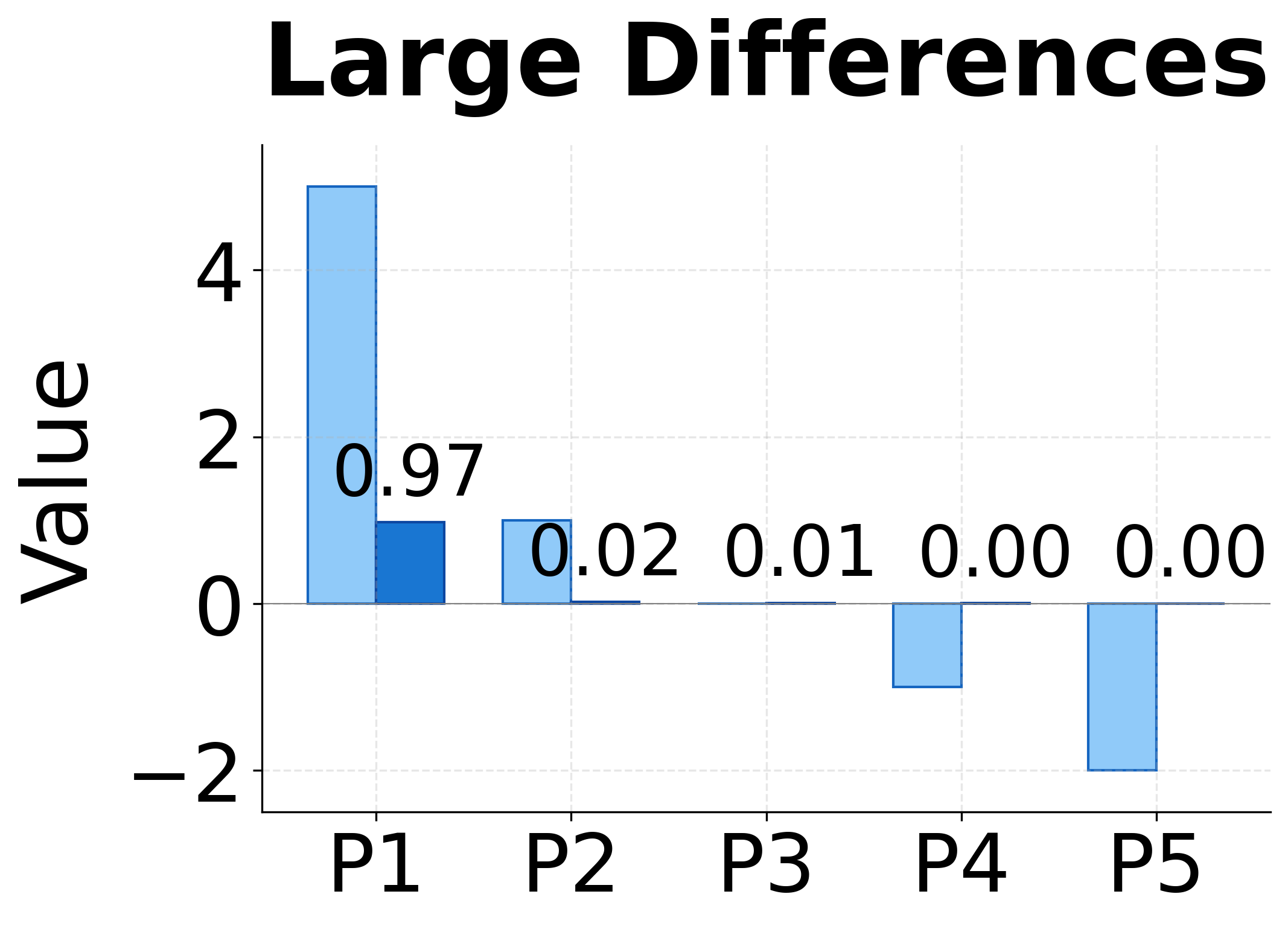

The visualization above demonstrates this amplification effect. With uniform scores, softmax produces uniform weights (0.20 each). Small score differences get amplified into clearer preferences. Large differences produce nearly one-hot attention, where almost all weight concentrates on the highest-scoring position.

Step 3: Computing the Context Vector

With attention weights in hand, we can finally answer our original question: "What information from the input should I use?" The answer is a weighted combination of all encoder states:

where:

- : the context vector, a single vector summarizing the relevant input information

- : how much weight to give to position (from step 2)

- : the information available at position (the encoder hidden state)

This weighted sum is the heart of attention. Each encoder state contributes to the context vector in proportion to its attention weight. If and all other weights are small, then will be dominated by , the information at position 3. If weights are more evenly spread, the context vector blends information from multiple positions.

The context vector has the same dimension as the encoder states, making it easy to combine with other parts of the model. The decoder uses alongside its own state to predict the next output token.

The Complete Picture

Let's trace through a concrete example. Suppose we're translating "The cat sat" and currently generating the French word "chat" (cat). The decoder state encodes that we've generated "Le" and are now producing the noun.

-

Alignment scores: The scoring function compares with each encoder state. It finds high compatibility with (the representation of "cat") and lower compatibility with ("The") and ("sat").

-

Attention weights: Softmax converts these scores into probabilities. Perhaps , , .

-

Context vector: The weighted sum produces a context vector dominated by the representation of "cat."

The decoder combines with and predicts "chat" as the next word. At the next step, when generating "noir" (black), the attention mechanism will shift focus to a different part of the input.

This dynamic, step-by-step focus is what makes attention effective. Rather than relying on a single compressed representation of the entire input, the model can look back at the original encoder states and select the information most relevant to each generation step.

Attention Weight Interpretation

Attention weights offer something rare in deep learning: interpretability. By examining which input positions receive high attention weights, we can understand what the model is "looking at" when making predictions.

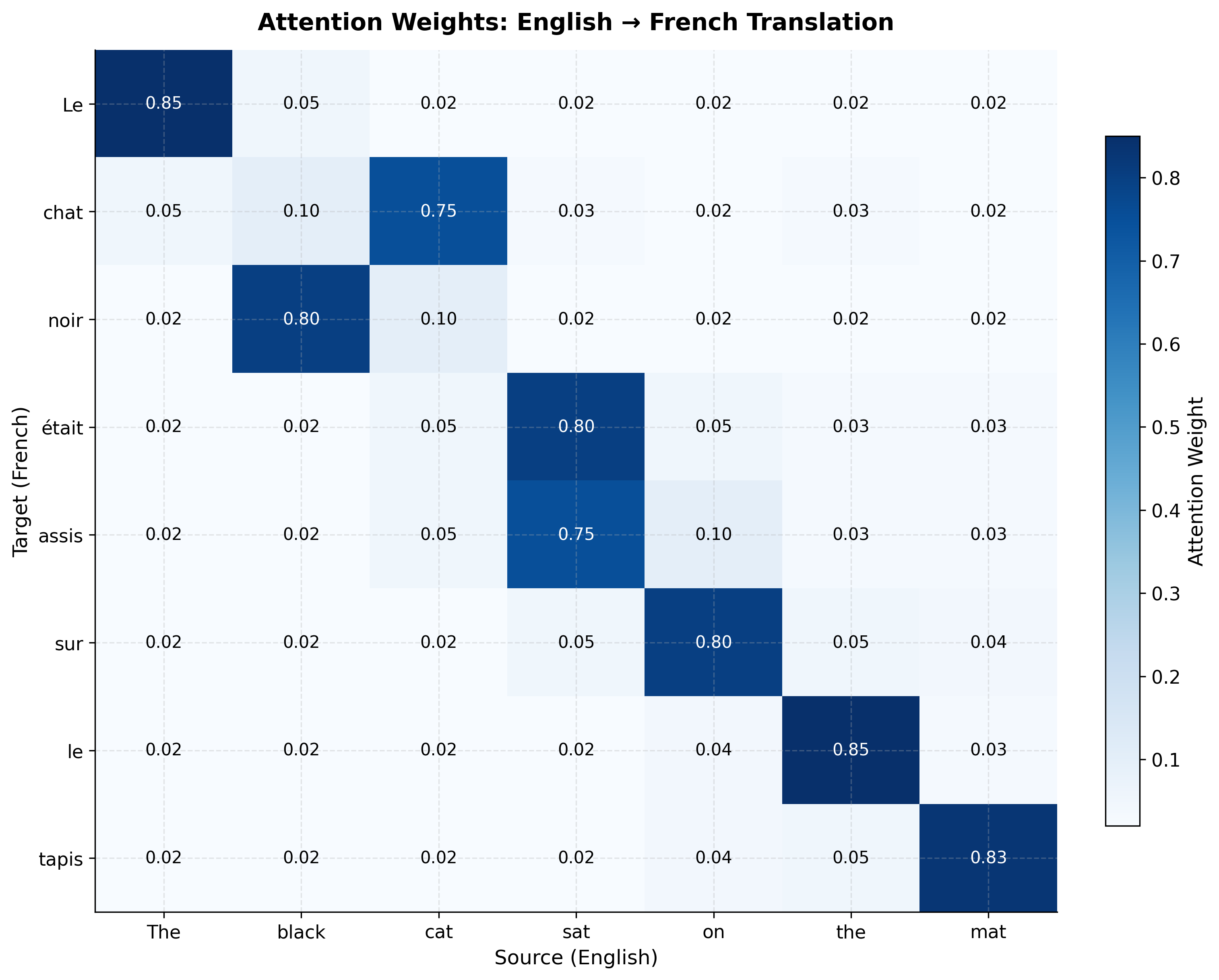

In machine translation, attention weights often reveal meaningful alignments between source and target languages. When translating "The black cat sat on the mat" to French "Le chat noir était assis sur le tapis", the model typically attends to:

- "cat" when generating "chat"

- "black" when generating "noir"

- "mat" when generating "tapis"

This alignment emerges automatically from training. The model learns that certain source words are most relevant for generating certain target words, without explicit supervision about word correspondences.

However, attention weights require careful interpretation:

- Weights show correlation, not causation: High attention on a position doesn't mean that position caused the output

- Distributed information: Important information might be spread across multiple positions with moderate weights

- Layer effects: In multi-layer models, different layers may attend to different aspects of the input

Despite these caveats, attention visualization remains one of the most valuable tools for understanding model behavior.

Handling Variable-Length Inputs

One of attention's most practical benefits is graceful handling of variable-length sequences. Traditional encoder-decoder models compress inputs of any length into a fixed-size vector, creating a fundamental mismatch: longer inputs must squeeze more information into the same space.

Attention sidesteps this entirely. The context vector is always a weighted average of encoder states, regardless of sequence length. For a 10-word sentence, we average over 10 states. For a 100-word paragraph, we average over 100 states. The mechanism scales naturally.

This property is crucial for tasks with highly variable input lengths:

- Document summarization: Articles range from a few sentences to thousands of words

- Question answering: Questions are short, but context passages can be lengthy

- Code generation: Function descriptions vary from one-liners to detailed specifications

Without attention, longer inputs would require either truncation (losing information) or larger hidden states (increasing memory and computation). Attention avoids both problems by dynamically selecting relevant information at each step.

Attention vs Pooling

Before attention became widespread, sequence models often used pooling operations to aggregate information. Mean pooling averages all hidden states, while max pooling takes the element-wise maximum. How does attention compare?

Mean pooling treats all positions equally by computing a simple average:

where:

- : the aggregated context vector (same dimension as hidden states)

- : the number of positions in the sequence

- : the hidden state at position

Each position receives weight , regardless of its content. This works when all parts of the input contribute equally to the output, but fails when relevance varies. In sentiment analysis, the phrase "not good" carries more weight than "the movie was", yet mean pooling gives them equal importance.

Max pooling extracts the strongest signal at each dimension independently:

where:

- : the -th dimension of the aggregated vector

- : the -th dimension of the hidden state at position

- : the maximum value across all positions

This captures salient features by selecting the most activated value for each dimension. However, it loses information about which positions contributed and cannot combine information from multiple positions in a nuanced way.

Attention provides learned, context-dependent weighting:

where:

- : the context vector

- : the learned attention weight for position (computed dynamically)

- : the hidden state at position

The weights are computed dynamically based on what the model needs at each step. Unlike mean pooling's uniform weights or max pooling's binary selection, attention learns which positions matter most for the current prediction. This flexibility makes attention strictly more expressive than fixed pooling strategies.

Consider the sentence "The movie was absolutely terrible" for sentiment classification. The table below compares how mean pooling and attention weight each word:

| Word | Mean Pooling | Attention |

|---|---|---|

| The | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| movie | 0.20 | 0.08 |

| was | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| absolutely | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| terrible | 0.20 | 0.75 |

The contrast is stark. Mean pooling treats "The" and "terrible" as equally important, diluting the sentiment signal across all words. Attention learns to focus on "terrible" (and to a lesser extent "absolutely"), producing a context vector that emphasizes what actually matters for sentiment classification.

| Method | Weights | Context-dependent | Interpretable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean pooling | Uniform () | No | No |

| Max pooling | Binary (0 or 1) | No | Partial |

| Attention | Learned | Yes | Yes |

Building Intuition with Code

The mathematics of attention translates directly into code. Let's implement the three-step process we just described: compute alignment scores, apply softmax to get attention weights, and produce a context vector through weighted summation. Working through a concrete example will solidify these concepts and reveal what happens inside the attention mechanism.

We have 5 encoder states representing the words in "The cat sat on mat". Each state is a 4-dimensional vector containing the hidden representation learned by the encoder. The decoder state, also 4-dimensional, represents what the model is currently trying to generate. In practice, these dimensions would be much larger (256 to 1024), but the small size here makes the computation easy to follow.

Now let's implement the attention mechanism. The function below follows our three-step formula exactly: compute dot product scores, apply softmax normalization, and return the weighted sum:

The attention weights show how much the model focuses on each input position. Notice that the weights sum to exactly 1.0, forming a valid probability distribution over input positions. In this random example, the weights are distributed based on how similar each encoder state is to the decoder state (measured by dot product). The context vector is a weighted combination of all encoder states, with dimensions matching the encoder hidden size. In a trained model, these similarities would reflect learned relevance patterns rather than random correlations.

Visualizing Attention Patterns

Attention weights are typically visualized as heatmaps, with rows representing decoder steps (outputs) and columns representing encoder positions (inputs). Let's create a visualization for a hypothetical translation task.

Several patterns emerge from this visualization:

- Diagonal tendency: Many languages share similar word order, so attention often follows a rough diagonal

- Reordering: French adjectives often follow nouns ("chat noir" vs "black cat"), visible in the swapped attention for "noir" and "chat"

- Many-to-one mapping: Both "était" and "assis" attend primarily to "sat", reflecting how French uses two words where English uses one

- Article alignment: Function words like "Le" and "le" align with their English counterparts

Attention in Practice: Sentiment Analysis

Let's see attention in a more complete example. We'll build a simple attention-based classifier for sentiment analysis, showing how attention helps identify which words drive the prediction.

This model uses a bidirectional LSTM to encode the input, then applies attention to create a single context vector for classification. The attention weights tell us which words the model considers most important.

Let's create a simple vocabulary and test the model:

Since this is an untrained model with randomly initialized weights, the attention distribution appears arbitrary. The model hasn't learned which words are semantically important. After training on labeled sentiment data, we would expect sentiment-bearing words like "great", "terrible", "loved", and "hated" to receive substantially higher attention weights (0.5-0.8), while function words like "the" and "was" would receive minimal attention (0.02-0.10).

Learned Attention Patterns

What would attention look like in a trained model? The table below shows realistic attention patterns for four sentiment sentences, with the highest-weighted word in each sentence highlighted:

| Sentence | the | movie/acting/plot | was | sentiment word | other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "the movie was great" | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.70 (great) | — |

| "the movie was terrible" | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.75 (terrible) | — |

| "the acting was not great" | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.35 (great) | 0.45 (not) |

| "really loved the plot" | 0.05 | 0.25 (plot) | — | 0.55 (loved) | 0.15 (really) |

These patterns reveal what we would expect from a trained model:

- Sentiment words dominate: "great", "terrible", and "loved" receive the highest weights

- Negation matters: In "not great", both "not" and "great" receive significant attention, as the model must combine them to understand the negated sentiment

- Function words ignored: Words like "the" and "was" consistently receive low attention

The Attention Computation Pipeline

Let's trace through the complete attention computation step by step. This pipeline applies regardless of the specific scoring function used. The five stages are:

- Encoder states (): The LSTM or other encoder produces one hidden state per input position

- Decoder state (): The decoder's current hidden state serves as the query

- Alignment scores (): A scoring function computes relevance between the query and each key

- Attention weights (): Softmax normalizes scores into a probability distribution

- Context vector (): Weighted sum of encoder states produces the final output

This context vector is then combined with the decoder state to predict the next token. Different attention variants (Bahdanau, Luong) differ primarily in how they compute the alignment scores in step 3.

Comparing Attention Mechanisms

We've established that attention requires a scoring function to measure relevance between decoder and encoder states. But what should this function look like? Different choices lead to different attention mechanisms, each with distinct trade-offs. Understanding these variants prepares you for the detailed treatments in upcoming chapters.

The fundamental question each scoring function answers is the same: "Given what I'm trying to generate (the decoder state) and what information is available (an encoder state), how compatible are they?" The answer is always a single number, the alignment score. But how we compute that number varies significantly.

Dot Product Attention (Luong)

The most direct approach treats compatibility as geometric alignment. Two vectors that point in similar directions should have high compatibility; vectors that are orthogonal should have zero compatibility. The dot product captures exactly this intuition:

where:

- : the decoder state at step , a vector of dimension

- : the encoder state at position , also dimension

- : the inner product, computed as

Geometrically, the dot product equals , where is the angle between the vectors. When both vectors point in the same direction (), the score is maximized. When they're perpendicular (), the score is zero. When they point in opposite directions (), the score is negative.

This simplicity is both a strength and a limitation. The dot product requires no learnable parameters, making it computationally efficient and easy to implement. However, it imposes a constraint: the decoder and encoder must have the same hidden dimension. More subtly, it assumes that compatibility can be measured purely through vector alignment in the existing embedding space, without any learned transformation.

Additive Attention (Bahdanau)

What if simple geometric alignment isn't expressive enough? Perhaps compatibility depends on complex, non-linear relationships between the decoder and encoder states. Additive attention addresses this by introducing a small neural network to compute scores:

where:

- : a weight matrix of dimension that projects the decoder state

- : a weight matrix of dimension that projects the encoder state

- : a weight vector of dimension that produces the final scalar

- : the hyperbolic tangent, introducing nonlinearity

- : the attention hidden dimension, a hyperparameter

Let's trace through what this formula does. First, projects the decoder state into a new space of dimension . Similarly, projects the encoder state into the same space. Adding these projections combines information from both states. The activation introduces nonlinearity, allowing the model to capture complex interactions. Finally, projects the result to a scalar score.

This approach has two key advantages. First, the learnable parameters (, , ) allow the model to discover what "compatibility" means for the specific task, rather than relying on pre-existing geometric relationships. Second, since we project both states into a common space, the encoder and decoder can have different dimensions. This flexibility is valuable when using different architectures for encoding and decoding.

The cost is additional computation and more parameters to learn. For each encoder position, we must perform two matrix multiplications and a nonlinear activation. In practice, this overhead is manageable, and the increased expressiveness often justifies the cost.

Scaled Dot Product Attention (Transformer)

The transformer architecture revived dot product attention but added a crucial refinement. The problem with vanilla dot products becomes apparent in high dimensions: scores can grow very large in magnitude, causing softmax to produce extremely peaked distributions.

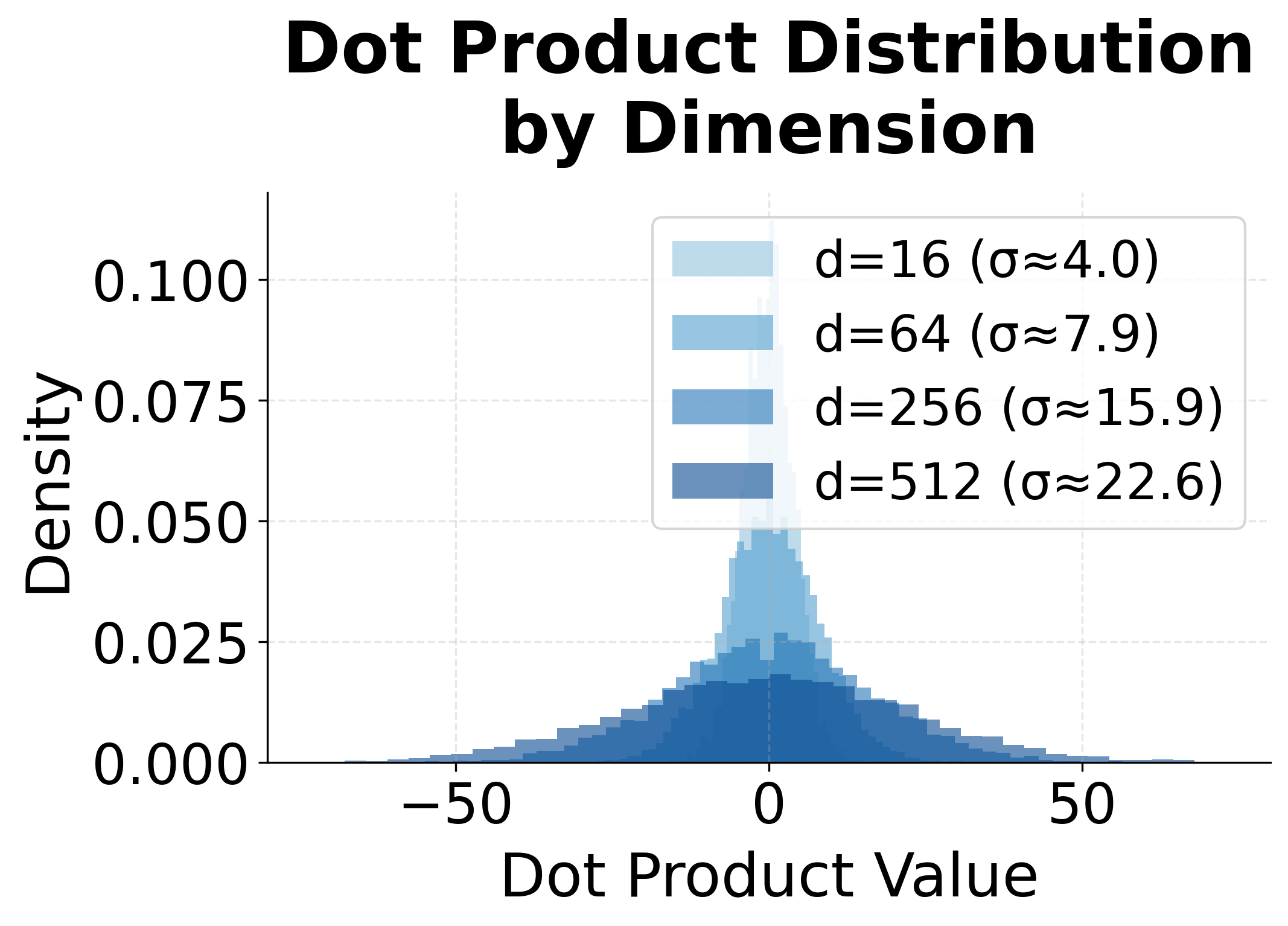

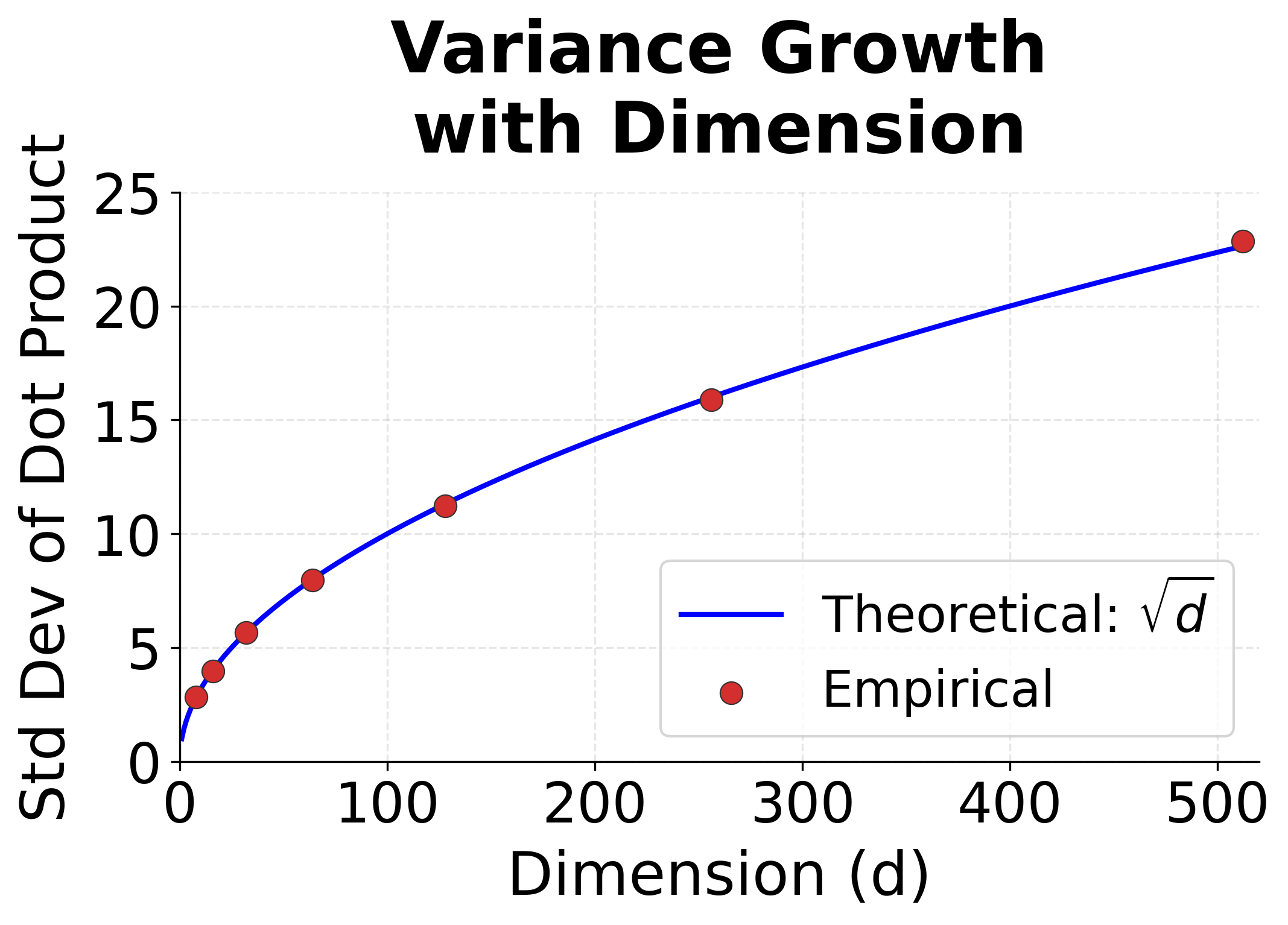

To understand why, consider what happens when we compute for vectors with dimensions. If each component is independently drawn from a distribution with zero mean and unit variance, the expected value of the dot product is zero, but its variance is approximately . For (a typical value), the standard deviation of scores is about 22. Scores this large cause softmax to assign nearly all probability mass to a single position, producing gradients close to zero for all other positions.

Scaled dot product attention fixes this by normalizing:

where:

- : the dimension of the key vectors

- : the scaling factor that stabilizes variance

Dividing by ensures the variance of scores remains approximately 1, regardless of dimension. This keeps softmax operating in a regime where gradients flow healthily during training. The fix is simple but essential for making attention work at scale.

The visualization confirms the scaling problem. As dimension increases, the distribution of dot product scores spreads dramatically. At , scores routinely exceed , which would cause softmax to produce extremely peaked distributions. Scaling by normalizes this spread back to a manageable range.

Choosing a Scoring Function

Each approach represents a different trade-off:

| Scoring Function | Parameters | Computational Cost | Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dot Product | None | Low (same dimension required) | |

| Additive | High (different dimensions OK) | ||

| Scaled Dot Product | None | Low (same dimension required) |

Dot product attention is fastest but least flexible. Additive attention is most flexible but requires more computation. Scaled dot product combines the efficiency of dot products with numerical stability for high dimensions.

In modern practice, scaled dot product attention dominates. Its efficiency allows transformers to use multiple attention heads in parallel, each learning different aspects of relevance. The lack of learnable parameters in the score function is offset by the projection matrices that create queries, keys, and values, which we'll explore in the transformer chapters.

Limitations and Impact

Attention improved sequence modeling significantly, but it comes with trade-offs worth understanding.

The most significant limitation is computational cost. Standard attention computes pairwise interactions between all query and key positions, resulting in complexity where is the sequence length. For a 1000-token document, this means a million attention computations per layer. This quadratic scaling motivates ongoing research into efficient attention variants like sparse attention, linear attention, and the various approximations used in models like Longformer and BigBird.

Another consideration is that attention weights, while interpretable, don't always tell the complete story. Research has shown that attention patterns can be manipulated without changing model predictions, and that high attention doesn't necessarily mean high importance for the final output. Gradient-based attribution methods sometimes provide more reliable explanations. Still, attention visualization remains valuable for debugging and building intuition about model behavior.

Despite these limitations, attention had a major impact on NLP. Before attention, sequence-to-sequence models struggled with long sequences and provided little insight into their decision-making. Attention enabled:

- State-of-the-art machine translation: The Bahdanau attention paper (2014) dramatically improved translation quality

- Interpretable models: Practitioners could finally see what their models were "looking at"

- Variable-length handling: Models could process inputs of any length without architectural changes

- The transformer architecture: Self-attention, where a sequence attends to itself, became the foundation of BERT, GPT, and virtually all modern language models

The attention mechanism went from a technique for improving translation to a core building block of modern deep learning for language.

Key Parameters

When implementing attention mechanisms, several parameters significantly impact model behavior:

-

Hidden dimension (

hidden_dim): The size of encoder and decoder hidden states. Larger values (256-1024) capture more nuanced representations but increase memory and computation. For attention to work with dot product scoring, encoder and decoder dimensions must match. -

Attention dimension (

d_a): For additive attention, this controls the size of the intermediate projection space. Typical values range from 64 to 512. Smaller values reduce parameters but may limit the model's ability to learn complex alignment patterns. -

Number of attention heads: In multi-head attention (covered in transformer chapters), this parameter controls how many parallel attention computations run simultaneously. Common values are 4, 8, or 16 heads, with the hidden dimension divided equally among heads.

-

Dropout rate: Applied to attention weights during training to prevent the model from relying too heavily on specific positions. Values of 0.1-0.3 are typical. Higher dropout encourages more distributed attention patterns.

-

Temperature scaling: An optional parameter that divides attention scores before softmax. Values less than 1.0 sharpen the distribution (more focused attention), while values greater than 1.0 flatten it (more uniform attention). The scaled dot product attention uses as an automatic temperature based on dimension.

Summary

Attention solves the information bottleneck in encoder-decoder models. Rather than compressing an entire input sequence into a single vector, attention allows the decoder to dynamically focus on relevant parts of the input at each generation step.

Key takeaways from this chapter:

- Soft lookup: Attention functions as a differentiable dictionary lookup, computing weighted combinations of values based on query-key similarity

- Three components: Every attention mechanism involves queries (what we're looking for), keys (what we compare against), and values (what we retrieve)

- Interpretability: Attention weights reveal which input positions the model considers relevant, enabling visualization and debugging

- Variable-length handling: Attention scales naturally to any input length, avoiding the fixed-size bottleneck of traditional encoders

- Beyond pooling: Unlike mean or max pooling, attention provides learned, context-dependent weighting that adapts to each prediction step

- Computational trade-off: The flexibility of attention comes at quadratic cost in sequence length, motivating efficient variants

In the following chapters, we'll examine specific attention mechanisms in detail. Bahdanau attention introduced the additive scoring function that made attention practical for machine translation. Luong attention explored simpler alternatives including dot product scoring. Understanding these foundations prepares you for the self-attention mechanism at the heart of transformers, where sequences attend to themselves to build rich contextual representations.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about attention mechanisms.

Comments