Learn how copy mechanisms enable seq2seq models to handle out-of-vocabulary words by copying tokens directly from input, with pointer-generator networks and coverage.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Copy Mechanism

Standard sequence-to-sequence models generate output tokens by selecting from a fixed vocabulary. This works well for common words, but what happens when the input contains a rare proper name, a technical term, or a number that the model has never seen? The decoder must either hallucinate a substitute or produce a generic placeholder. Neither outcome is satisfactory.

Copy mechanisms solve this problem by allowing the decoder to directly copy tokens from the input sequence. Instead of being forced to generate every output token from scratch, the model can "point" to input positions and reproduce those tokens verbatim. This matters for tasks like summarization, where preserving names and facts is critical, and for handling out-of-vocabulary words that would otherwise be lost.

This chapter explores how copy mechanisms work, from the foundational pointer networks to the practical pointer-generator architecture. You'll learn how models compute copy probabilities, blend copying with generation, and handle the challenging case of out-of-vocabulary tokens. By the end, you'll understand why copy mechanisms became a standard component in production summarization systems.

The Vocabulary Problem in Generation

Before diving into copy mechanisms, let's understand the problem they solve. Traditional seq2seq models have a fixed output vocabulary, typically the most frequent words in the training data.

Now consider what happens when we encounter input with rare words:

The words "Nakamura," "Stanford," and "conference" are critical for an accurate summary, yet a standard decoder cannot produce them. It would have to replace them with <unk> tokens or substitute similar but incorrect words. Copy mechanisms solve this directly: let the decoder point to these words in the input and copy them.

Pointer Networks: The Foundation

To understand copy mechanisms, we must first grapple with a fundamental question: how can a neural network select items from a variable-length input sequence? Traditional neural networks produce outputs of fixed size, but when copying from input, we need to point to one of positions where changes with each input.

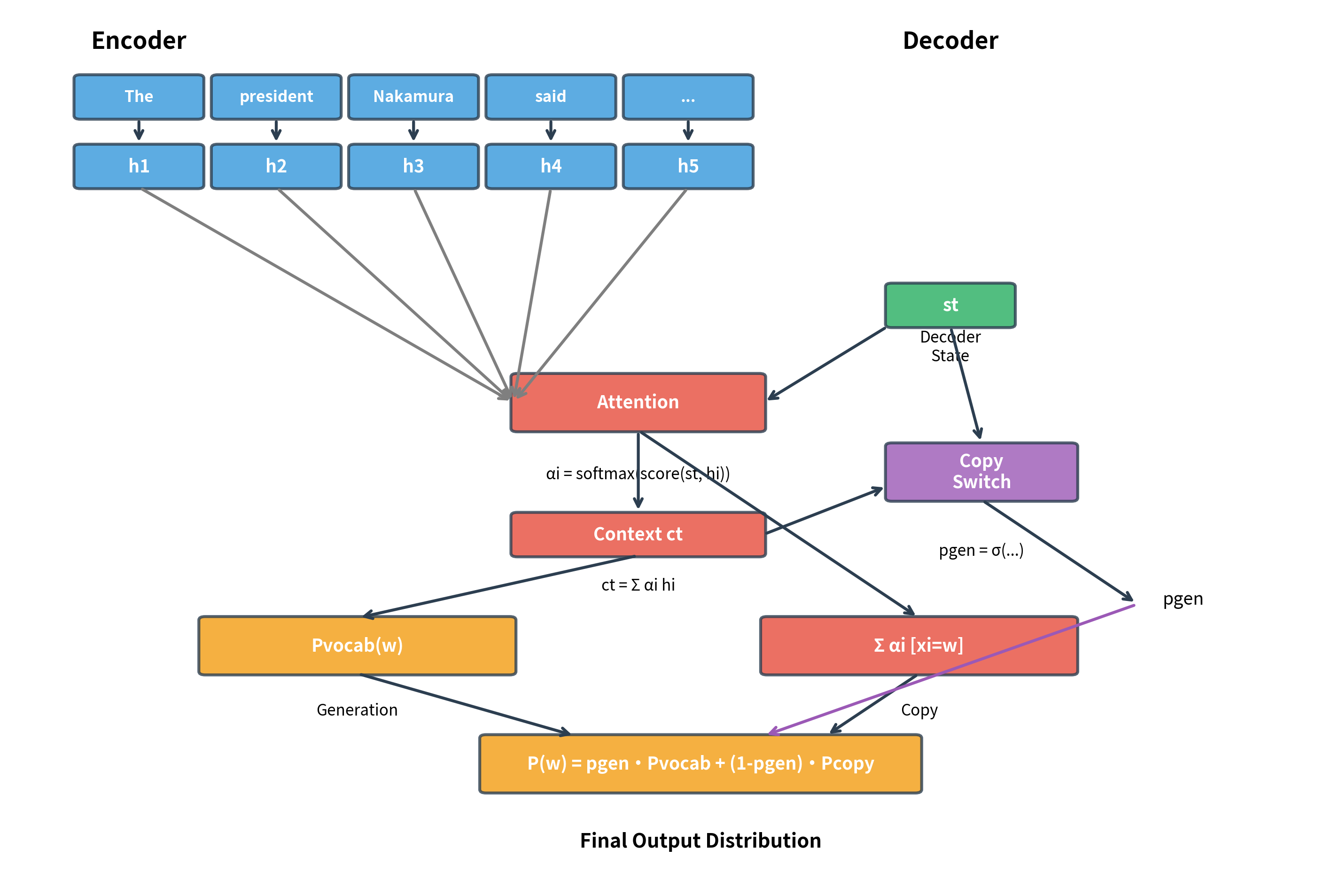

Pointer networks, introduced by Vinyals et al. in 2015, solve this by repurposing attention. Recall that attention computes a weighted combination of encoder states, producing weights that sum to 1 across all input positions. These weights already form a probability distribution over the input. The key insight is simple: instead of using attention weights only to compute context vectors, we can interpret them directly as "pointing" probabilities.

A pointer network is a sequence-to-sequence model where the output at each step is a pointer to an element in the input sequence. Instead of generating tokens from a vocabulary, it uses attention over the input to select which input position to "point to."

Let's trace through the mechanics. At each decoder step, we have a decoder hidden state that encodes what we've generated so far. We also have encoder outputs representing each input position. The pointer mechanism computes a score for each input position, measuring how relevant that position is given the current decoder state:

- Project both representations into a common space using learned weight matrices

- Combine them through addition (Bahdanau-style) and pass through a nonlinearity

- Compute a scalar score for each position using a learned vector

- Normalize with softmax to obtain a valid probability distribution

The resulting probabilities tell us: "Given what I've generated so far, how likely should I point to each input position?"

The pointer probabilities form a valid distribution over input positions. At each decoding step, the model can select which input token to copy by sampling from or taking the argmax of this distribution.

Computing the Copy Probability

A pure pointer network can only copy from the input, but real text generation requires both copying and generating. Consider summarizing "Dr. Chen announced the results." We want to copy "Dr. Chen" (a rare name) but generate common words like "announced" and "the" from our vocabulary. How does the model decide which strategy to use at each step?

The solution introduces a soft switch between two modes: generating from vocabulary versus copying from input. Rather than making a hard binary choice, we compute a generation probability that smoothly interpolates between the two strategies. When is high, the model favors generation; when low, it favors copying.

What information should determine this switch? Intuitively, the decision depends on:

- The context vector : What part of the input is the model attending to? If attention focuses on a rare word, copying makes sense.

- The decoder state : What has the model generated so far? This captures the "momentum" of the generation process.

- The previous token : What did we just output? After generating "Dr.", we likely want to copy the following name.

We combine these three signals through a linear combination, then squash the result to using the sigmoid function:

where:

- : the probability of generating from the vocabulary (vs. copying from input)

- : the sigmoid function, , which maps any real number to the range

- : the context vector from attention at decoder step

- : the decoder hidden state at step

- : the decoder input embedding at step (typically the previous output token)

- : learnable weight vectors that determine how much each input contributes to the decision

- : a learnable bias term that shifts the default behavior toward generating or copying

The model learns the weights during training. It discovers patterns like "when the context vector indicates a rare word and the decoder state suggests we're in the middle of a named entity, favor copying." These patterns emerge from the data without explicit programming.

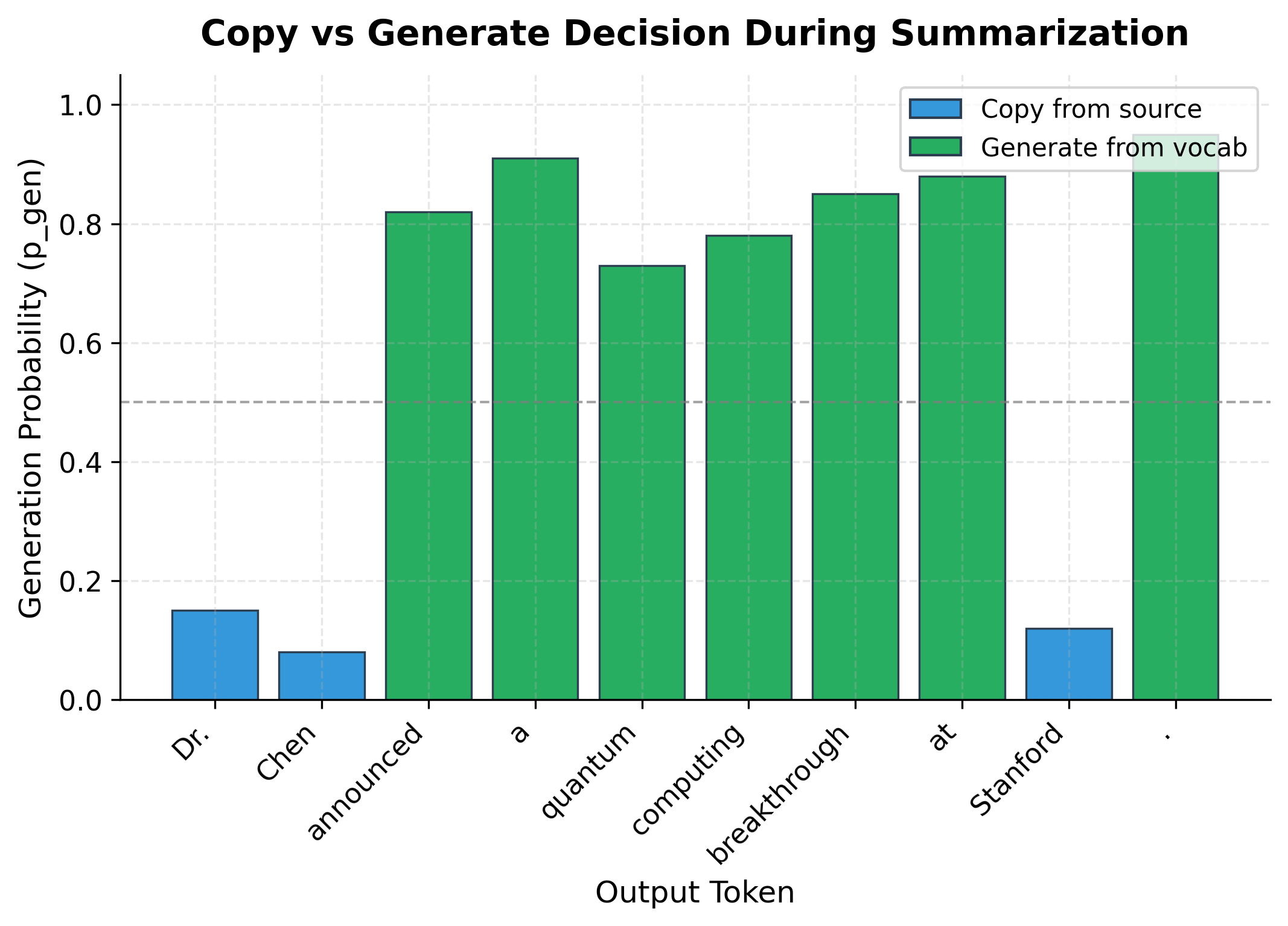

The output reveals how the copy switch behaves: values near 0 indicate the model prefers copying, while values near 1 indicate generation. In practice, the model learns to produce low for rare words and names, and high for common function words.

Mixing Generation and Copying

We now have two probability distributions: one over the vocabulary (from the decoder's softmax) and one over input positions (from pointer attention). We also have a switch that tells us how much to trust each. How do we combine them into a single output distribution?

The naive approach would be to make a hard choice: either generate or copy. But this loses information and creates discontinuities that hurt gradient flow during training. Instead, we use as a mixing coefficient that smoothly blends both distributions.

Consider a word that we might want to output. There are three cases:

-

is only in the vocabulary: It can only be generated, so its probability comes entirely from , scaled by .

-

is only in the input (OOV): It can only be copied, so its probability comes from the attention weights on positions containing , scaled by .

-

is in both: It receives probability from both sources, which are added together.

This leads to the final probability formula:

where:

- : the final probability of outputting word

- : the generation probability from the copy switch

- : the probability assigned to by the decoder's vocabulary softmax

- : the attention weight (pointer probability) for input position

- : the token at input position

- : sum over all positions where the input token equals

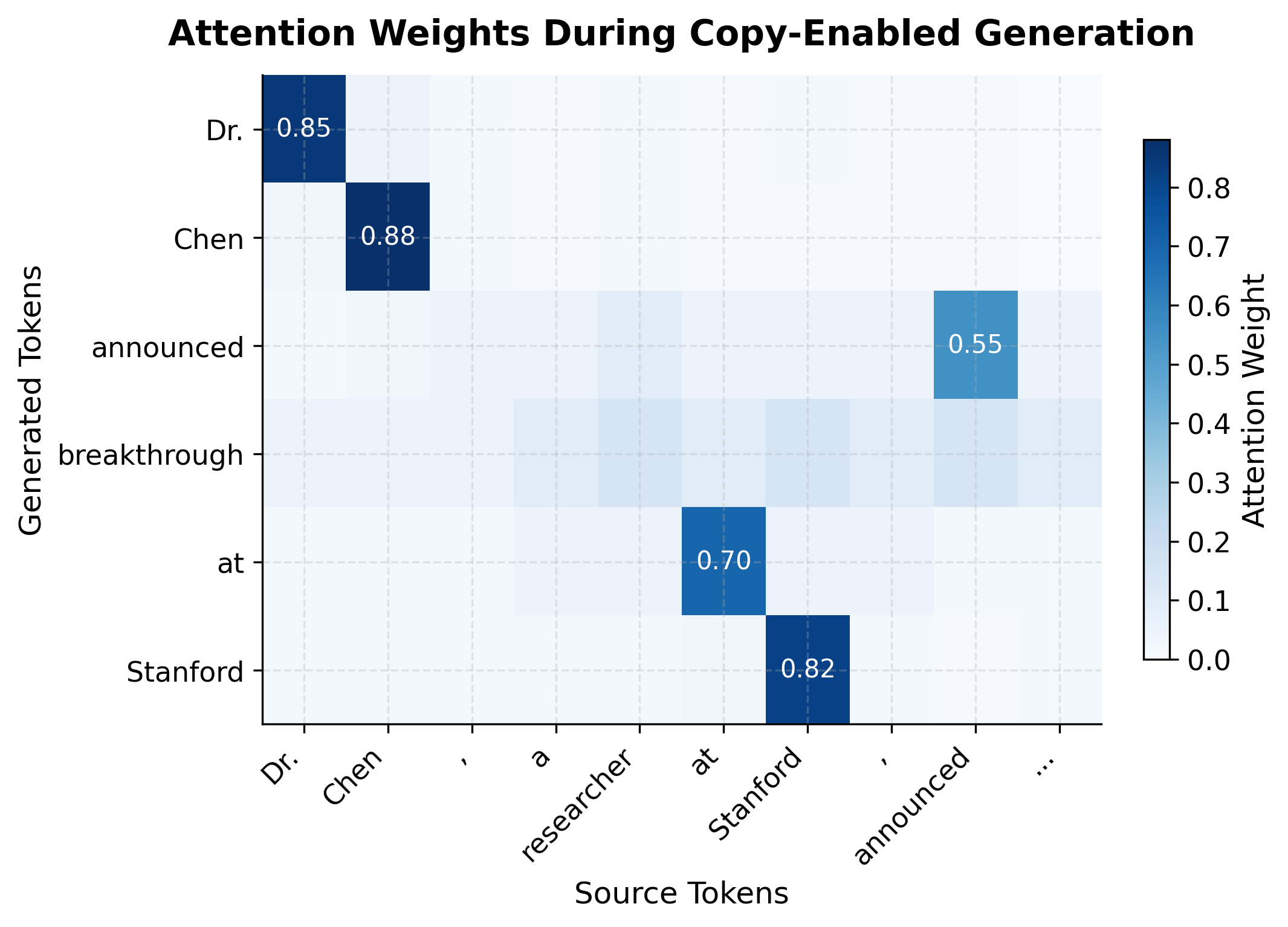

The summation deserves attention. If a word appears multiple times in the input (e.g., "the" might appear at positions 2, 7, and 15), we sum the attention weights from all those positions. This makes intuitive sense: if the model attends to any occurrence of "the" in the input, that attention contributes to the probability of outputting "the."

Let's trace through a concrete example. Suppose we're generating a summary and the input contains "the president Nakamura said." Our vocabulary includes common words but not "Nakamura." At the current step:

- The vocabulary distribution assigns: ,

- The pointer distribution assigns: (the), (president), (Nakamura), (said)

- The copy switch outputs: (favoring copying)

For "Nakamura" (OOV, only copyable):

For "said" (in both vocab and input):

The OOV word "Nakamura" receives substantial probability through copying alone, while "said" gets a boost from both sources.

: Final probability distribution combining generation and copy contributions. Words in both vocabulary and source (like "the" and "said") receive probability from both channels. OOV words like "Nakamura" can only be copied, receiving their entire probability from the copy mechanism. {#tbl-probability-combination}

The table reveals the mechanics of probability combination. "Nakamura" receives its entire probability from copying, since it's not in the vocabulary. "the" and "said" appear in both the source and vocabulary, so they receive contributions from both channels. With , the copy channel dominates, which is appropriate when the model needs to preserve specific names from the input.

The output confirms our mathematical analysis. "Nakamura," despite being out-of-vocabulary, receives the highest probability through the copy mechanism. The model can produce this word in its output even though it never appeared in training. Meanwhile, words like "said" and "the" receive probability from both generation and copying, with their contributions weighted by .

This combination of generation and copying solves the OOV problem while preserving the model's ability to generate fluent, grammatical text. The soft switch learns to route rare words through copying and common words through generation.

The Pointer-Generator Network

The pointer-generator network, introduced by See et al. (2017) for abstractive summarization, combines the ideas above into a cohesive architecture. It extends the standard attention-based seq2seq model with a copy mechanism, enabling it to both generate words from the vocabulary and copy words from the source document.

Let's implement a complete pointer-generator decoder step:

The output distribution sums to 1.0, confirming it's a valid probability distribution. The decoder produces probabilities over all tokens in the vocabulary, and the top predictions show which tokens are most likely at this step. In practice, these probabilities would be used either for greedy decoding (selecting the argmax) or for beam search (maintaining multiple hypotheses).

Copy Mechanism for Summarization

Abstractive summarization is the canonical application for copy mechanisms. Summaries must preserve key facts, names, and numbers from the source document while also rephrasing and condensing the content. The pointer-generator architecture excels at this balance.

Let's trace through how the model would generate a summary:

Handling Out-of-Vocabulary Words

The copy mechanism's most important contribution is handling out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words. Without copying, rare words would be replaced with <unk> tokens, destroying factual accuracy. With copying, these words can appear in the output even if they never occurred in training.

The implementation requires extending the vocabulary dynamically for each input:

The OOV handler assigns extended vocabulary IDs to words not in the base vocabulary. "Dr.", "Chen", "discovery", and "Stanford" receive IDs starting from the base vocabulary size (8), allowing the copy mechanism to produce these tokens even though they weren't in the original vocabulary. This dynamic vocabulary extension is computed per-input, so different source documents can have different OOV words.

During training, we need to handle the case where target tokens are OOV:

Attention Visualization for Copy

Visualizing attention patterns reveals when and what the model copies. High attention on specific source positions often indicates copying, especially when is low.

Coverage Mechanism

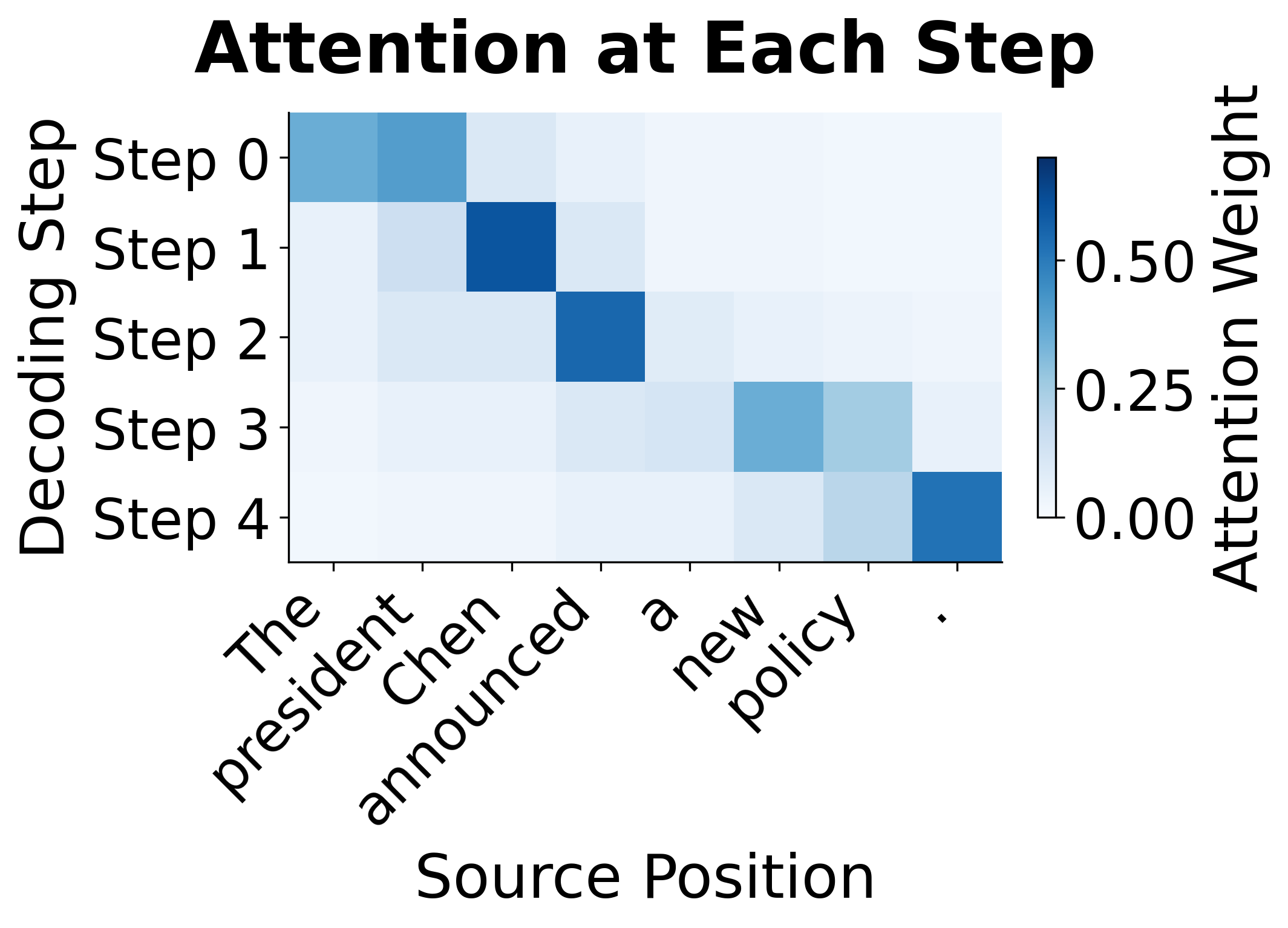

One issue with attention-based models is repetition: the model may attend to the same source positions multiple times, generating repetitive output. The coverage mechanism addresses this by tracking which source positions have already been attended to.

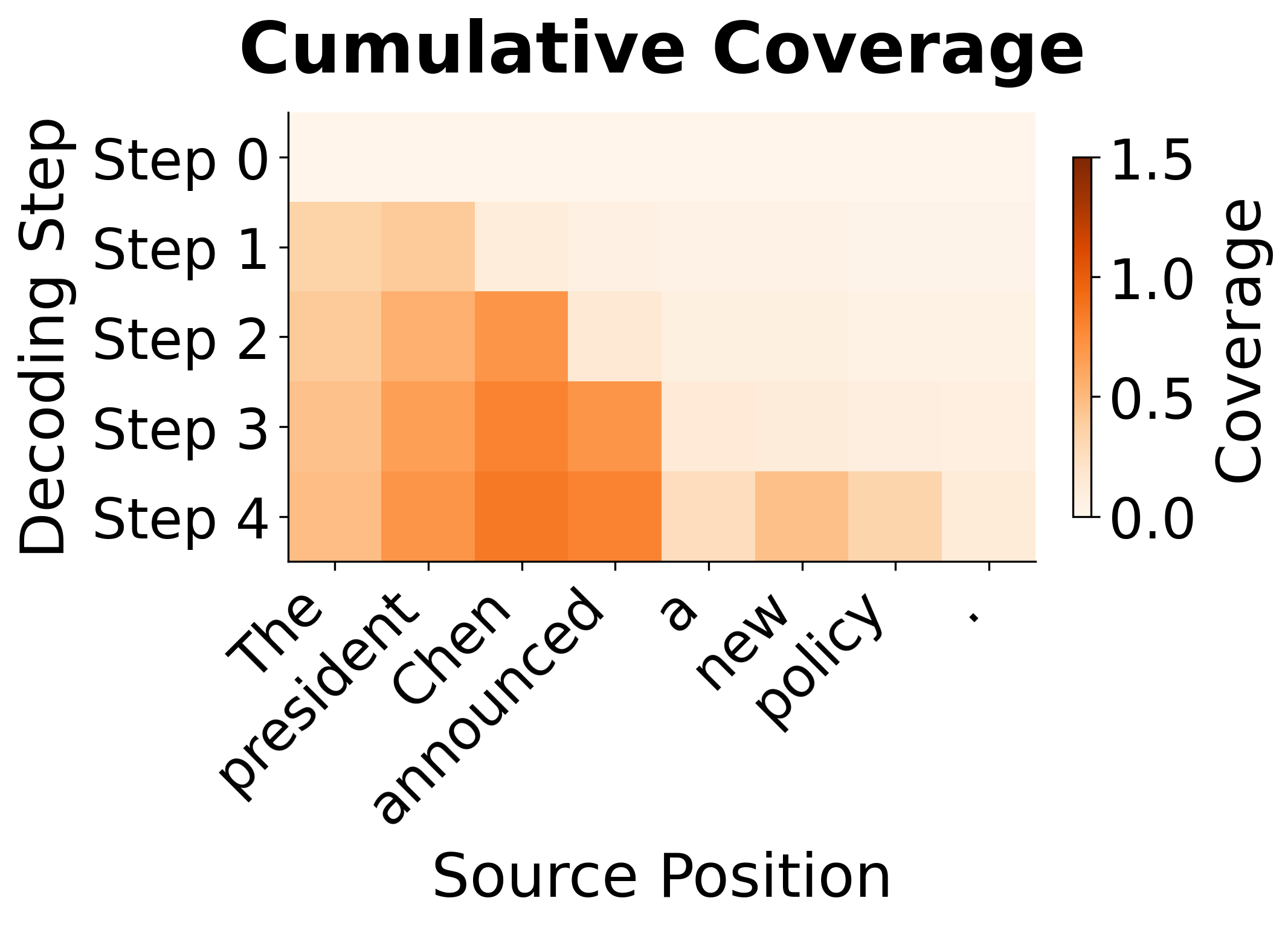

Coverage maintains a running sum of attention distributions from all previous decoder steps. This coverage vector is used to penalize re-attending to already-covered positions, reducing repetition in the output.

The coverage vector at decoder step accumulates all previous attention distributions:

where:

- : the coverage vector at step , with one value per source position

- : the attention distribution at previous step

- The sum runs over all previous decoder steps from to

Each element represents how much total attention has been paid to source position so far. High values indicate positions that have been heavily attended; low values indicate under-attended positions.

This coverage vector is incorporated into the attention computation, encouraging the model to attend to positions with low coverage. Additionally, a coverage loss explicitly penalizes re-attending to already-covered positions:

where:

- : the coverage loss at step

- : the current attention weight on source position

- : the accumulated coverage at position

- : takes the element-wise minimum

The intuition behind the function: the loss is only incurred when both the current attention and the past coverage are high for the same position. If either is low, the contribution to the loss is small. This allows the model to attend to new positions freely while penalizing redundant attention to already-covered content.

The visualization shows how coverage accumulates during generation. In the left panel, each row represents the attention distribution at a single decoding step. The right panel shows the cumulative coverage before each step. Notice how "president" (position 1) quickly accumulates high coverage after step 0, discouraging the model from re-attending to it. By step 4, the coverage mechanism has effectively "used up" the early positions, encouraging the model to attend to later, less-covered positions.

Practical Training Considerations

Training pointer-generator networks requires careful attention to several practical details.

Teacher forcing with copy targets: During training, when the target token appears in the source, the model should learn to copy it. This requires computing whether each target token is copyable and adjusting the loss accordingly.

Additional training techniques include:

- Scheduled sampling for : Early in training, the model may not learn when to copy effectively. Some implementations use scheduled sampling to gradually shift from forced copying to learned .

- Gradient clipping: The combined distribution can have very small probabilities, leading to large gradients. Gradient clipping helps stabilize training.

Limitations and Impact

The copy mechanism, while powerful, has important limitations that practitioners should understand.

The mechanism assumes that words worth copying appear verbatim in the source. For tasks requiring paraphrasing or where source words need morphological changes (e.g., "announced" to "announcement"), pure copying falls short. The model must learn to generate these variants, which may still be OOV. Some extensions address this by copying at the subword level, allowing partial matches and morphological flexibility.

Copy mechanisms add computational overhead. Computing the extended vocabulary distribution and tracking OOV words increases memory usage and slows inference. For very long source documents, the attention computation over all source positions becomes expensive. Hierarchical attention and sparse attention variants can mitigate this, but at the cost of additional complexity.

The balance between copying and generating is learned implicitly through . In practice, models sometimes over-copy, producing extractive rather than abstractive summaries, or under-copy, hallucinating facts. Careful tuning of the coverage loss weight and training data curation helps, but achieving the right balance remains challenging.

Despite these limitations, copy mechanisms significantly improved neural text generation. Before their introduction, neural summarization systems struggled with factual accuracy, producing fluent but unfaithful summaries. The pointer-generator architecture showed that neural models could preserve factual content while still generating abstractive summaries. This work paved the way for modern summarization systems and influenced the design of retrieval-augmented generation approaches that similarly blend retrieved content with generated text.

Summary

Copy mechanisms extend sequence-to-sequence models to handle the fundamental vocabulary limitation of neural text generation. The key concepts from this chapter:

-

Pointer networks use attention weights as a probability distribution over input positions, enabling the model to "point to" and copy input tokens rather than generating from a fixed vocabulary.

-

The generation probability acts as a soft switch between generating from vocabulary and copying from input. It's computed from the decoder state, context vector, and input embedding, allowing the model to learn when each strategy is appropriate.

-

The final distribution combines generation and copy probabilities. Words appearing in both vocabulary and input receive probability from both sources, while OOV words can only be produced through copying.

-

Pointer-generator networks integrate these components into a practical architecture for tasks like summarization, where preserving names, numbers, and rare words is essential for factual accuracy.

-

OOV handling requires extending the vocabulary dynamically for each input, tracking which source positions contain which OOV words, and ensuring the loss function properly handles extended vocabulary targets.

-

Coverage mechanisms address repetition by tracking which source positions have been attended to and penalizing re-attention, improving output diversity and coherence.

The copy mechanism was an important step in making neural text generation practical for real-world applications where factual accuracy matters. While modern large language models have largely subsumed these techniques through massive vocabularies and in-context learning, understanding copy mechanisms provides insight into the fundamental challenges of neural text generation and the solutions researchers developed to address them.

Key Parameters

When implementing pointer-generator networks:

Copy Switch Parameters:

hidden_dim: Dimension of encoder/decoder hidden states. Larger values capture more nuanced representations but increase computation. Typical values: 256-512 for small models, 512-1024 for larger ones.embed_dim: Dimension of token embeddings fed to the copy switch. Should match the embedding layer used in the decoder.

Attention Parameters:

hidden_dimin attention: Must match encoder output dimension. The attention mechanism projects both encoder and decoder states to this dimension for score computation.

Coverage Parameters:

coverage_loss_weight: Hyperparameter controlling how strongly to penalize re-attending to covered positions. Values between 0.5 and 2.0 are common. Higher values reduce repetition more aggressively but may hurt fluency.

Training Parameters:

max_oov_per_batch: Maximum number of OOV words to track per batch. Limits memory usage for the extended vocabulary. Typical values: 50-200 depending on document length.gradient_clip: Maximum gradient norm for clipping. Values around 2.0-5.0 help stabilize training when probabilities become very small.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about copy mechanisms in neural text generation.

Comments