Learn how BART trains language models using diverse text corruptions including token deletion, shuffling, sentence permutation, and text infilling to build versatile encoder-decoder models.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Denoising Objectives

Language models learn by predicting missing or corrupted text. Masked language modeling replaces tokens with [MASK], and span corruption hides contiguous chunks. But what if we corrupted text in more diverse ways? Token deletion, shuffling, sentence permutation, and document rotation all introduce different types of noise that force models to learn different aspects of language structure.

Denoising objectives generalize the idea of text reconstruction. Instead of a single corruption strategy, they apply multiple transformations that break different properties of natural text. The model learns to recover the original by developing robust understanding of word order, sentence boundaries, document structure, and semantic coherence. BART (Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformers) pioneered this approach, showing that combining diverse noise types produces models that excel at both understanding and generation.

In this chapter, we'll explore the major denoising transformations, understand what each one teaches the model, implement them from scratch, and see how combining them creates versatile language models.

The Denoising Autoencoder Framework

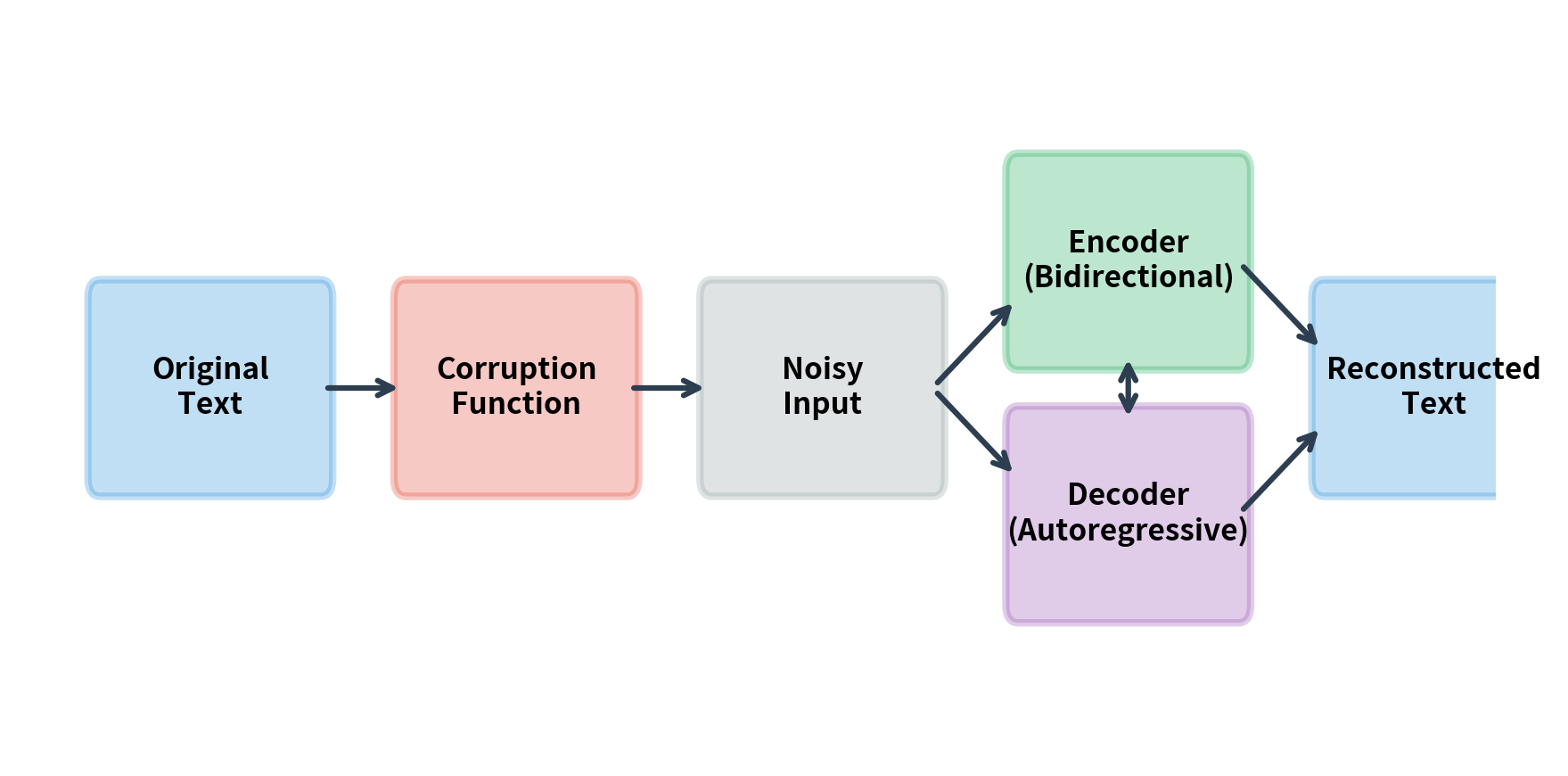

Denoising objectives treat pretraining as an autoencoding problem. The model receives corrupted input and must reconstruct the original. This differs from standard autoencoders, which simply copy input to output. By corrupting the input, we force the model to learn meaningful representations rather than trivial identity mappings.

A model trained to reconstruct clean data from corrupted inputs. By learning to remove noise, the model develops robust representations that capture the underlying structure of the data rather than surface-level patterns.

Formally, given original text , we apply a corruption function to obtain noisy input . The model learns parameters to maximize the probability of recovering from . The training objective minimizes the negative log-likelihood of reconstructing the original:

where:

- : the denoising loss we want to minimize

- : the original, uncorrupted text sequence

- : the corrupted input produced by applying the corruption function to

- : the model parameters (encoder and decoder weights)

- : the probability the model assigns to the original text given the corrupted input

The negative log transforms the probability (a value between 0 and 1) into a loss: when the model assigns high probability to the correct reconstruction, the loss is low. When the model is uncertain or wrong, the loss is high. Minimizing this loss trains the model to reliably reconstruct clean text from corrupted inputs.

The choice of corruption function determines what the model must learn. Simple corruptions like random token replacement teach local dependencies. Complex corruptions like document rotation teach global structure. By combining multiple corruption types, we can train models that understand language at every level.

The encoder-decoder architecture fits naturally with denoising. The encoder processes the corrupted input bidirectionally, building rich representations. The decoder generates the original text autoregressively, learning to produce coherent output. This combination gives BART-style models the best of both worlds: bidirectional encoding for understanding and autoregressive decoding for generation.

Token Deletion

Token deletion randomly removes tokens from the input sequence. Unlike masking, which replaces tokens with a placeholder, deletion removes them entirely. The model must determine which tokens are missing and where they belonged.

This corruption is more challenging than masking because position information is lost. With masking, the model knows exactly where each missing token should go. With deletion, it must infer both the missing content and its location from context alone.

The corrupted sequence is shorter than the original. With a 20% deletion probability, we expect roughly 2 tokens to be removed from a 9-token sentence. The actual number varies due to random sampling. Notice that the deleted tokens could be anywhere in the sequence, and the remaining tokens are simply concatenated without any placeholder marking where deletions occurred. The model must learn to expand the sequence during reconstruction, inserting the missing tokens in the correct positions.

Token deletion teaches several important skills. First, the model learns robust representations that don't depend on specific tokens being present. Second, it learns about syntactic obligatoriness, recognizing when articles, prepositions, or other grammatical elements are missing. Third, it develops sensitivity to semantic completeness, detecting when content words have been removed.

Deletion Rate Selection

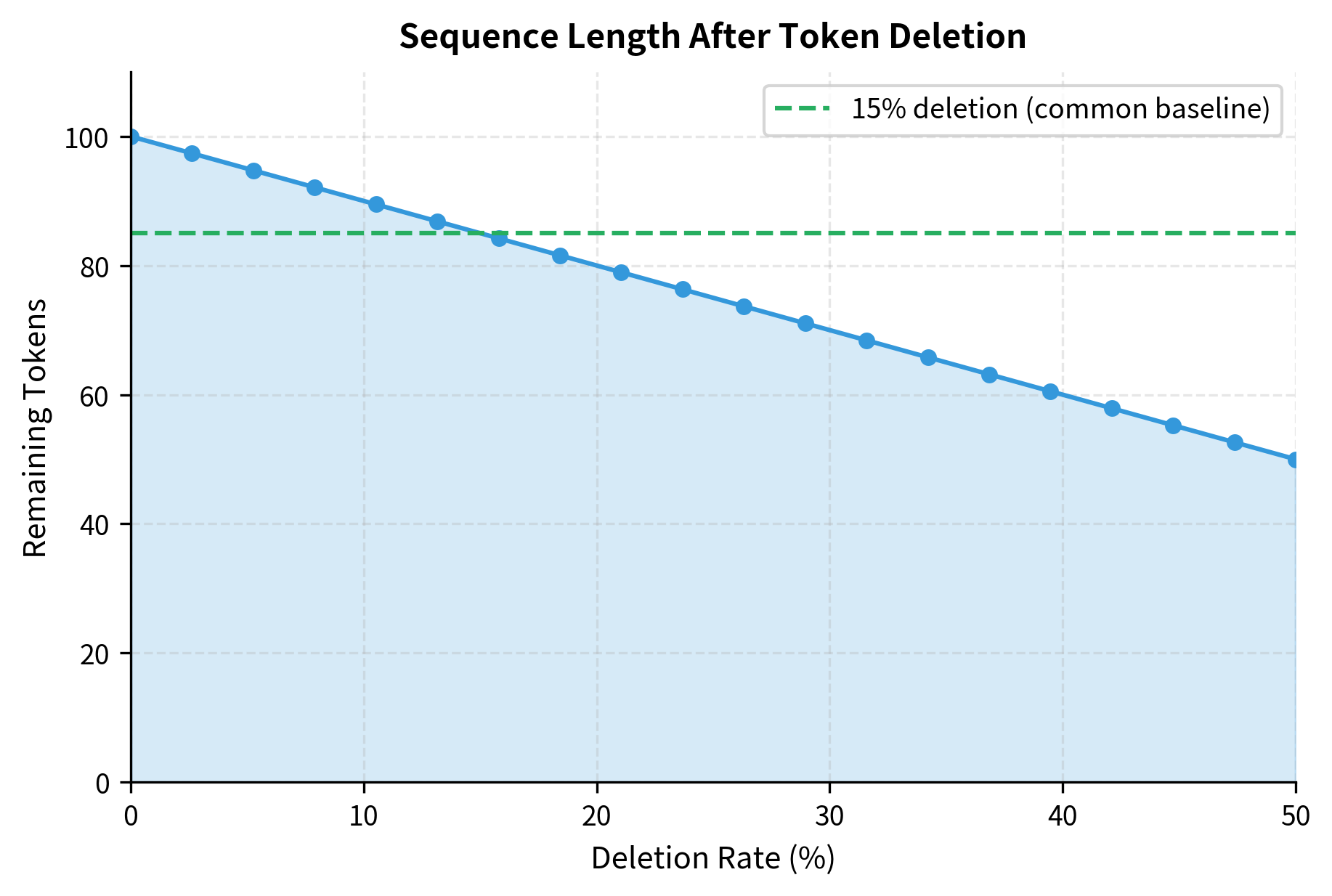

The deletion probability controls the difficulty of reconstruction. Too low (under 5%), and most sequences pass through unchanged, providing little training signal. Too high (over 30%), and too much information is lost for reliable reconstruction.

A 15% deletion rate, matching BERT's masking rate, provides a reasonable balance. This removes enough tokens for meaningful learning while preserving sufficient context for accurate reconstruction. Note that BART's final configuration uses text infilling (30%) rather than pure token deletion, but 15% remains a common baseline when experimenting with deletion-based corruption.

Token Shuffling

Token shuffling permutes tokens within the sequence, breaking the original word order. The model must learn to reorder tokens into grammatically correct sequences. This corruption targets a model's understanding of syntax and word order constraints.

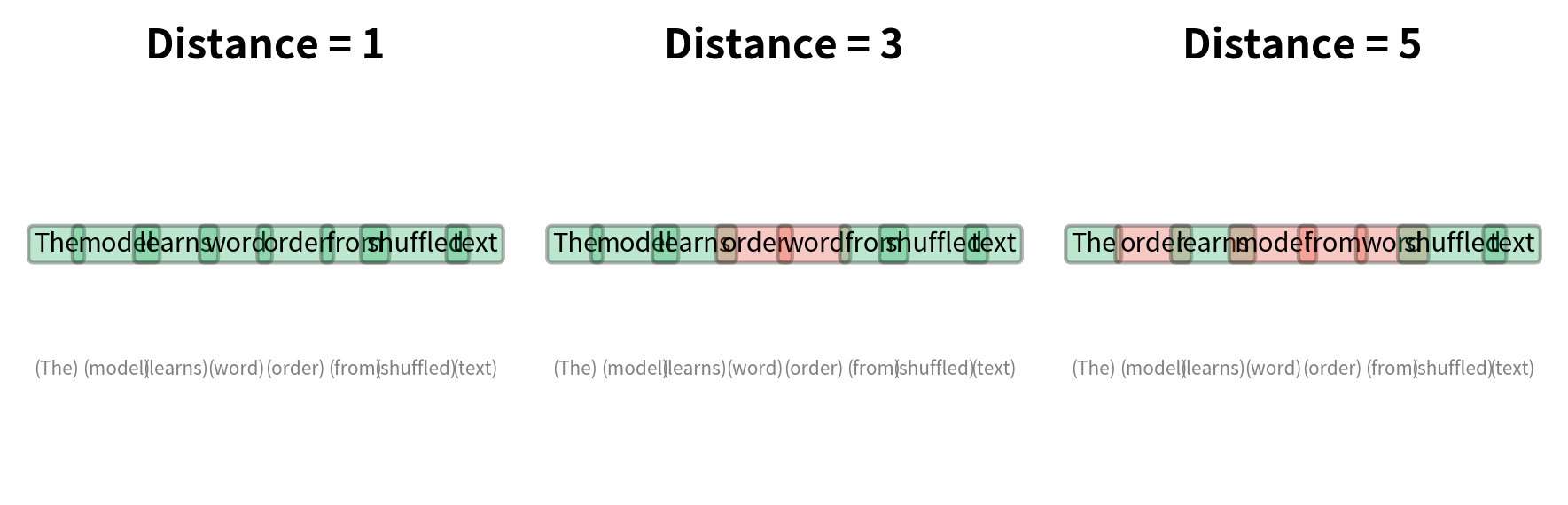

Unlike deletion, shuffling preserves all tokens. The information is present but scrambled. The model must learn that "dog the lazy" should become "the lazy dog" based on its understanding of English syntax.

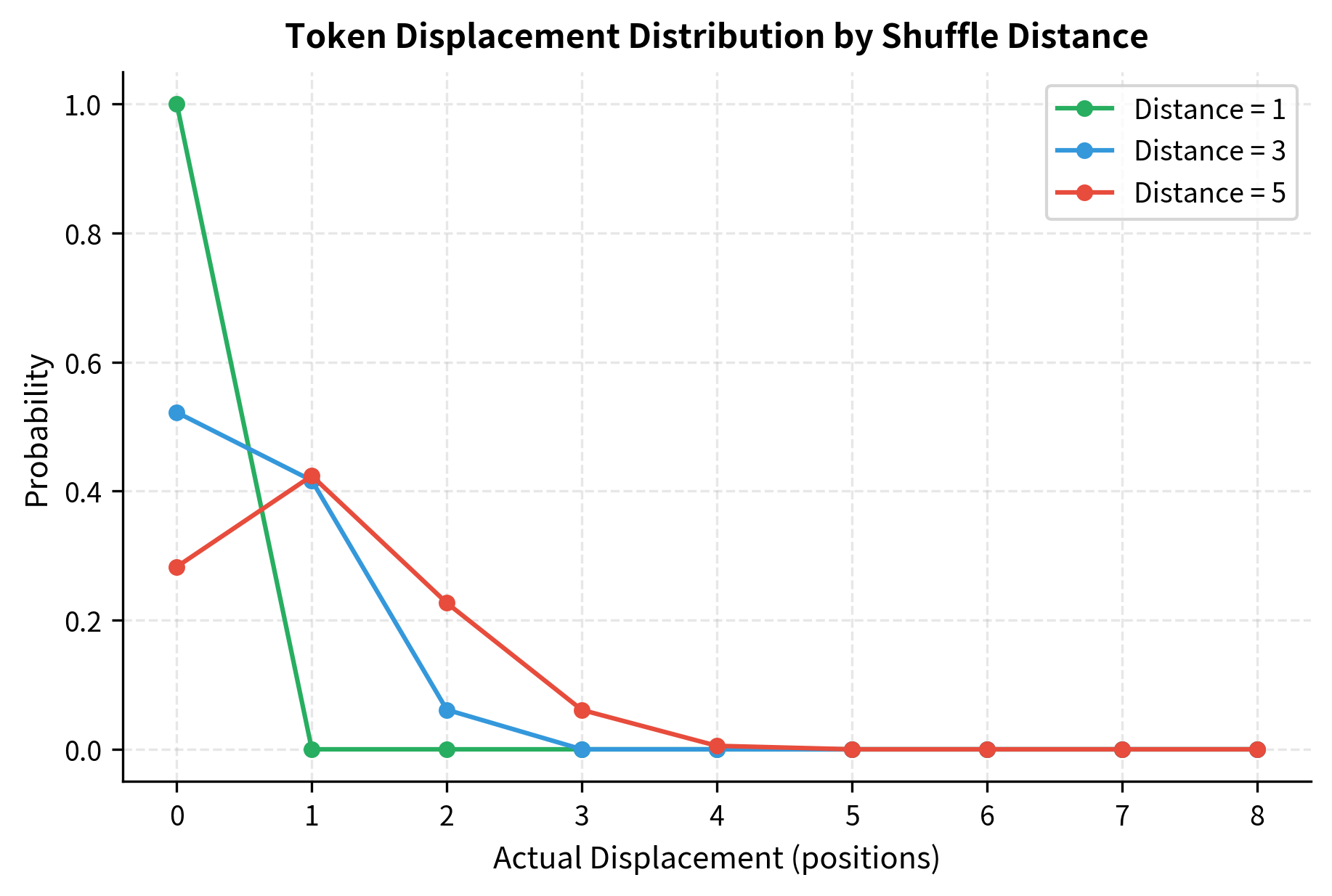

With a shuffle distance of 3, tokens can move up to 3 positions from their original location. The algorithm adds random noise to each position, then sorts by the noisy positions, creating local permutations while preserving rough ordering. This approach ensures that tokens tend to stay near their original positions rather than being scattered randomly across the entire sequence.

Smaller distance values produce local permutations that are easier to correct. Larger values create more severe scrambling that requires understanding longer-range dependencies.

Local vs. Global Shuffling

Local shuffling (small distance) tests whether the model understands adjacent word relationships. Phrases like "the quick" or "brown fox" have strong local coherence that the model should detect.

Global shuffling (large distance) tests whether the model understands sentence-level structure. The subject-verb-object ordering of English, or the tendency for adjectives to precede nouns, becomes important when tokens move far from their original positions.

Sentence Permutation

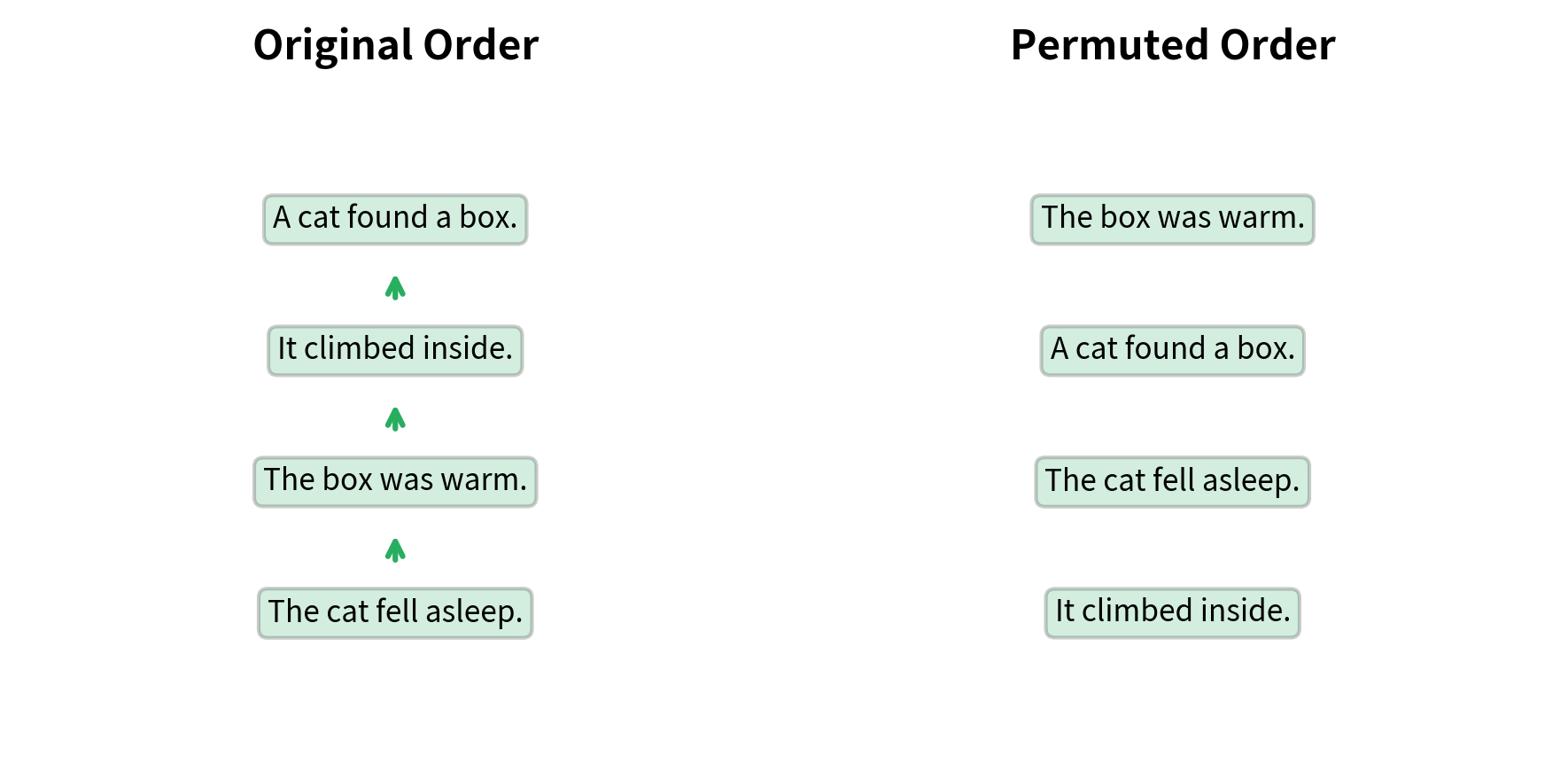

Sentence permutation shuffles the order of sentences within a document. While token shuffling breaks word-level order, sentence permutation breaks discourse-level structure. The model must learn how sentences relate to each other and what ordering makes a coherent document.

This corruption helps with tasks that require understanding document structure, such as summarization, document classification, and multi-document reasoning.

The permuted document contains all the original information but in scrambled order. Notice how "Later it woke up hungry" appears without prior context about the cat falling asleep, making the narrative harder to follow. The model must learn to detect these coherence breaks and recognize that certain sentences require prior context to make sense.

Discourse Coherence

Sentence permutation forces the model to learn discourse markers and rhetorical relationships. Words like "however," "therefore," "first," and "finally" provide strong signals about sentence ordering. Pronoun resolution also provides clues: "it" in "It was a sunny day" must refer to something previously mentioned.

Narrative text is harder because events unfold in a specific order. Scientific writing with clear logical progression is easier because explicit markers guide the ordering. Creative writing with complex temporal structure is hardest because the "correct" order may not be unique.

Document Rotation

Document rotation moves a random portion of the document from the beginning to the end, or vice versa. The text is "rotated" around a randomly chosen pivot point. This corruption breaks the document's beginning and end while preserving internal structure.

The rotated text starts mid-sentence with "was a brave knight..." rather than the natural opening "Once upon a time." The model must recognize this unnatural beginning and identify where the original document started. The classic fairy tale opening provides a strong signal about document structure, teaching the model to recognize common opening patterns like "Once upon a time," "In this paper," or "Chapter 1."

Start Token Identification

BART uses a special approach for document rotation: it always starts the corrupted input at a sentinel token that marks where the original document began. This simplifies the task slightly but still requires the model to learn document structure.

Without the sentinel, the model must learn to identify document beginnings from content alone. Phrases like "In this paper," "Chapter 1," or narrative openings like "It was a dark and stormy night" signal document starts. The model develops sensitivity to these patterns through the rotation objective.

The sentinel token provides an explicit signal about where rotation occurred. The model's job becomes somewhat easier: generate the correct sequence given knowledge of where the original start was.

Text Infilling

Text infilling combines aspects of span corruption and token deletion. Random spans of text are replaced with a single mask token, and the model must generate the missing content. Unlike span corruption where each span gets a unique sentinel, infilling uses a single mask token for all gaps.

This is more challenging because the model must determine both the content and the length of each missing span. A single [MASK] might represent one word or ten words.

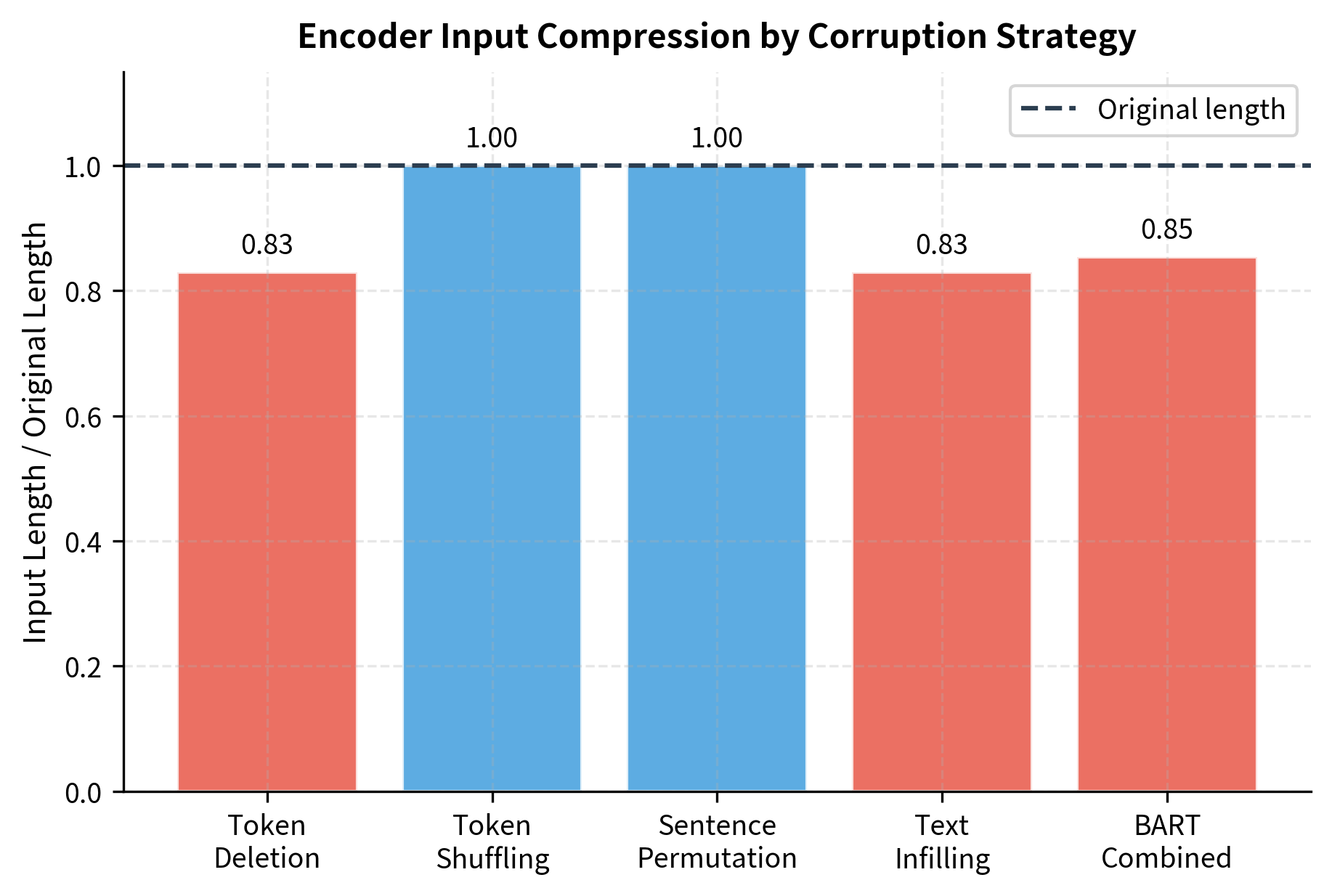

Multiple tokens collapse into single [MASK] placeholders. The 8-token sentence shrinks to fewer tokens because each span, regardless of length, becomes a single mask. The model must learn to generate the correct number of tokens for each mask, a more challenging objective than predicting a fixed number of tokens per placeholder.

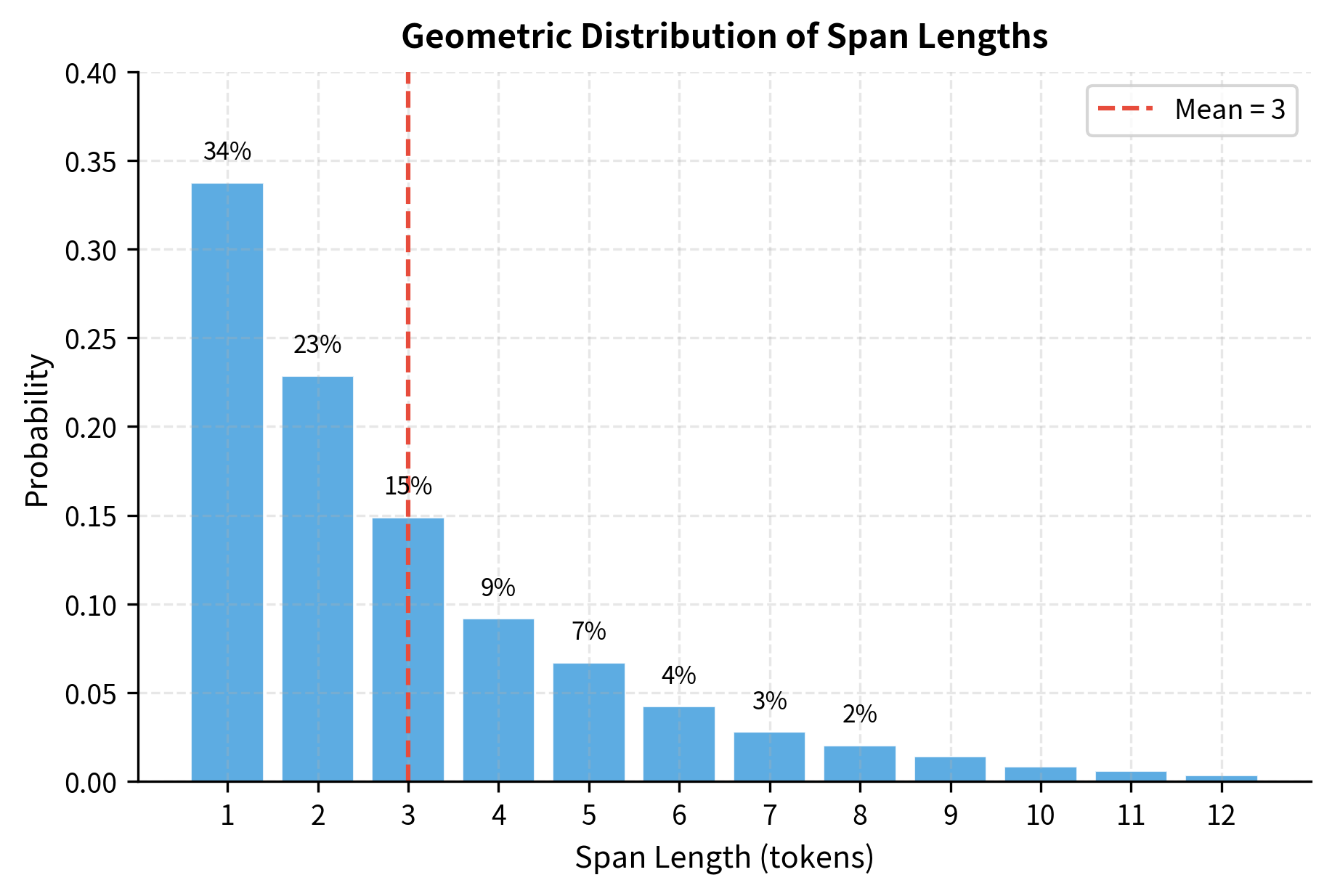

Span Length Distribution

The geometric distribution controls how span lengths are sampled. With a mean of 3, most spans are short (1-2 tokens), but the heavy tail allows occasional longer spans that test phrase-level understanding.

The distribution shows that roughly one-third of spans contain just a single token, similar to standard MLM. However, the remaining two-thirds contain multiple tokens, forcing the model to generate coherent phrases rather than isolated words. This balance between token-level and phrase-level prediction is key to text infilling's effectiveness.

BART-Style Combined Denoising

BART combines multiple corruption types to create a versatile denoising objective. The original BART paper explored five transformations:

- Token masking: Replace tokens with

[MASK](similar to BERT) - Token deletion: Remove tokens entirely

- Text infilling: Replace spans with single

[MASK]tokens - Sentence permutation: Shuffle sentence order

- Document rotation: Rotate document around random point

The best-performing configuration used text infilling as the primary corruption, combined with sentence permutation. This combination forces the model to learn both local (word-level) and global (document-level) structure.

The corrupted version demonstrates both transformations working together. Sentences appear in a different order, and multiple spans have been replaced with [MASK] tokens. The sequence is noticeably shorter because each masked span, regardless of how many tokens it contained, becomes a single placeholder. This compression is a key efficiency advantage of text infilling: the encoder processes fewer tokens while the decoder still generates the full original.

The compression from text infilling provides computational savings during training. The encoder processes shorter sequences, reducing the quadratic attention cost, while the decoder still learns to generate the full original sequence.

Comparing Corruption Strategies

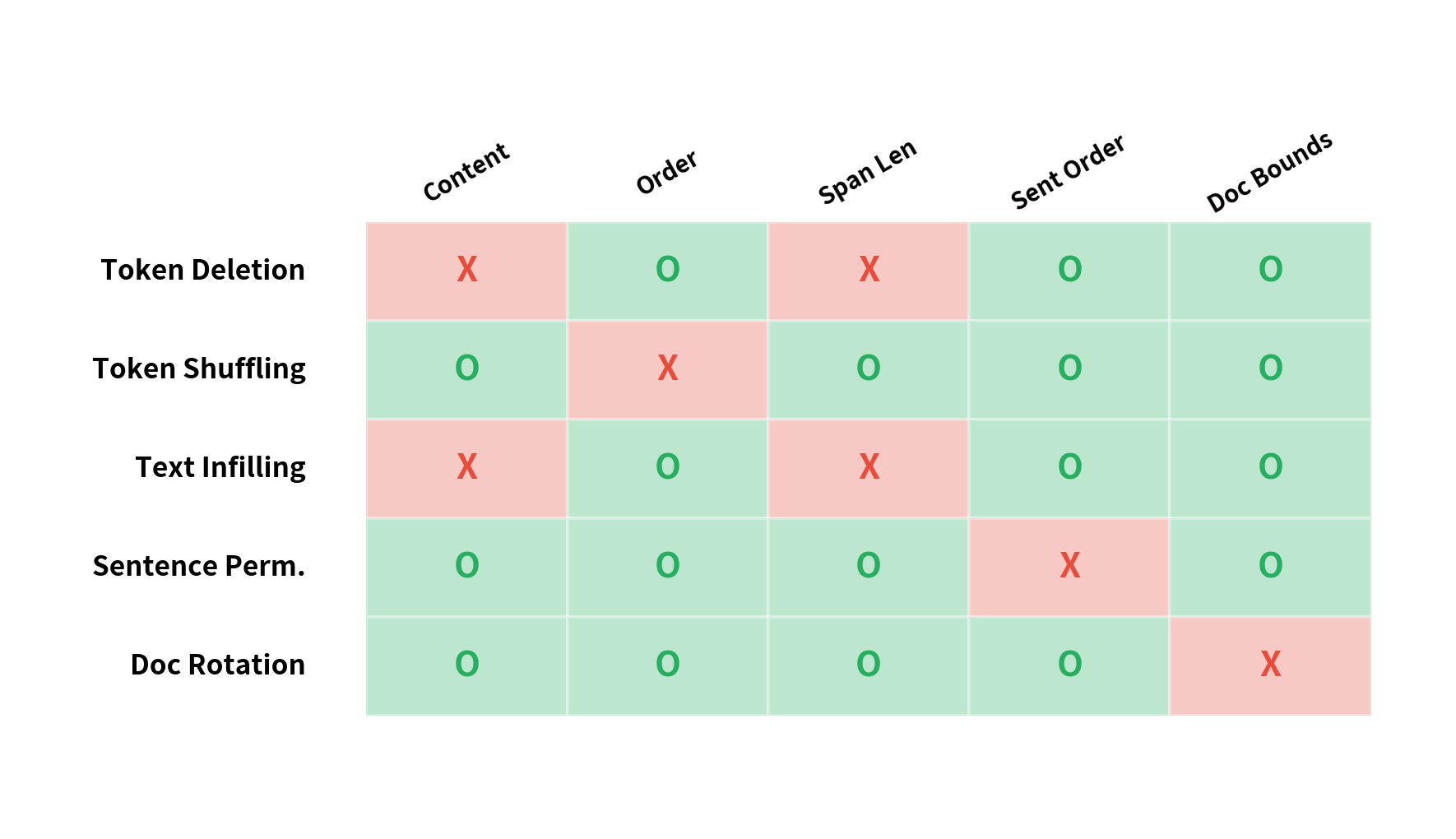

Different corruptions teach different aspects of language understanding. Let's compare how each strategy transforms the same input.

Each corruption breaks different properties:

- Token deletion: Removes specific words, breaking local completeness

- Token shuffling: Scrambles word order, breaking syntax

- Text infilling: Hides contiguous chunks, breaking both content and length

- Sentence permutation: Reorders sentences, breaking discourse flow

The choice of corruption depends on the target application. For generation tasks, text infilling works best because it trains the decoder to produce variable-length outputs. For understanding tasks, combining multiple corruptions produces more robust representations.

Training with Denoising Objectives

Training a denoising model requires carefully balancing the encoder and decoder. The encoder must build useful representations from corrupted input. The decoder must learn to generate coherent text conditioned on those representations.

The training loop follows a straightforward sequence-to-sequence pattern:

- Sample a batch of documents from the training corpus

- Apply corruption (text infilling and sentence permutation)

- Pass corrupted input through the encoder

- Generate the original text with the decoder using teacher forcing

- Compute cross-entropy loss on target tokens

- Backpropagate gradients and update parameters

The training objective is standard sequence-to-sequence cross-entropy. The difference from other seq2seq tasks lies entirely in how the training pairs are constructed: the corrupted input is the source, and the original text is the target.

Hyperparameter Considerations

Key hyperparameters for denoising pretraining include:

-

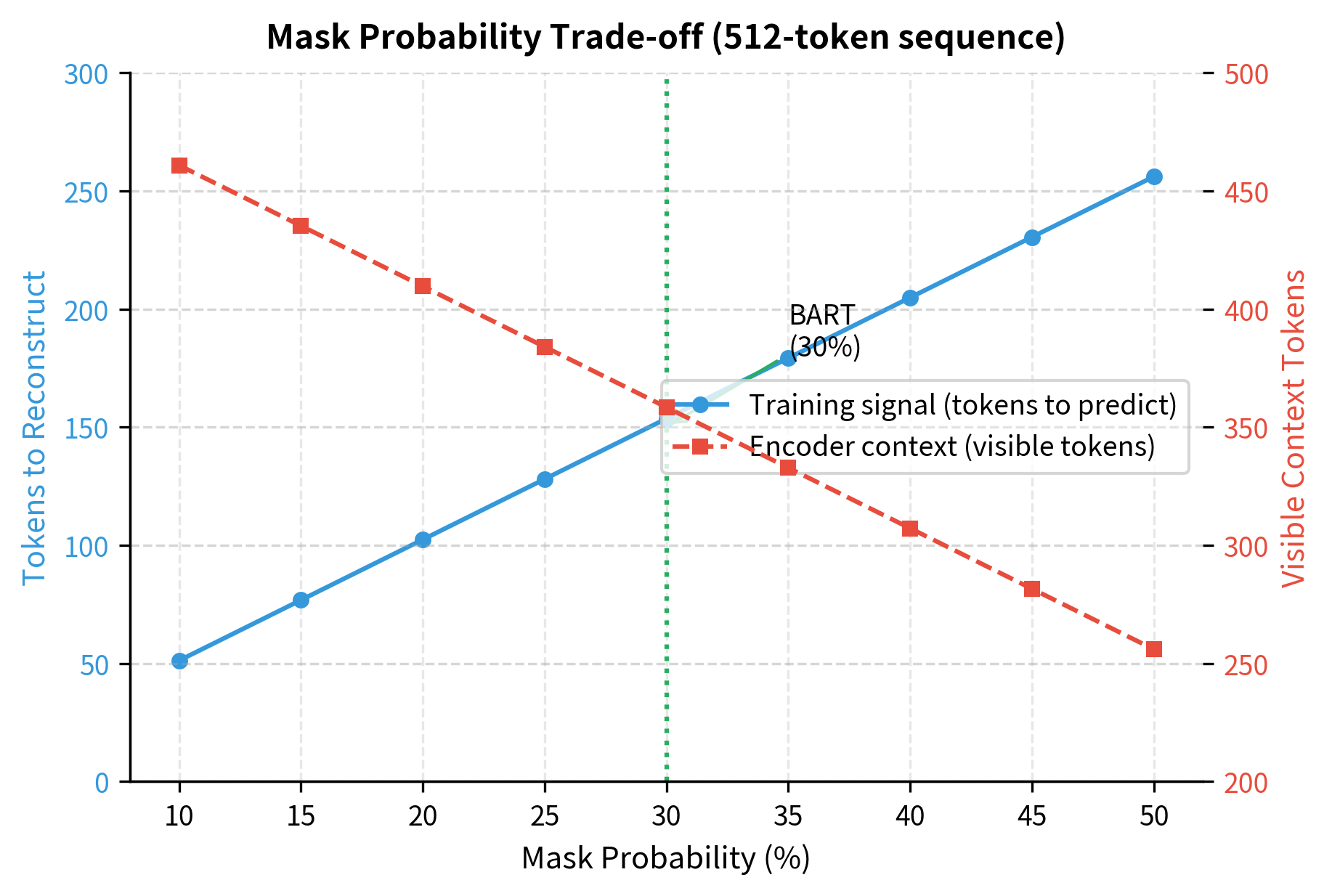

Mask probability (default: 30% for BART): Higher than BERT's 15% because infilling is more efficient. Each mask token can represent multiple original tokens.

-

Mean span length (default: 3): Balances short spans (token-level learning) with longer spans (phrase-level learning). Span lengths follow a geometric distribution with parameter , producing a mean of 3 tokens. Most spans are short (1-2 tokens), with occasional longer spans.

-

Sentence permutation probability: BART applies permutation to all documents. Some variants skip permutation for single-sentence inputs.

-

Learning rate: Standard transformer learning rates (1e-4 to 5e-4) with warmup work well.

-

Batch size: Large batches (2048+ tokens per GPU) help with the noisy gradients from aggressive corruption.

Limitations and Impact

Denoising objectives have transformed language model pretraining, but they come with tradeoffs that shape their practical applications.

The most fundamental limitation is the mismatch between pretraining and downstream tasks. During pretraining, the model always receives corrupted input and must produce the original. During fine-tuning and inference, the model receives clean input and must produce novel output. This gap means that denoising models may not immediately transfer their reconstruction skills to generation tasks without fine-tuning. BART addresses this partially through its autoregressive decoder, which learns generation patterns even during denoising, but the task distribution shift remains a concern for zero-shot applications.

Computational efficiency presents another tradeoff. Aggressive corruption reduces the input sequence length (especially with text infilling), which speeds up encoding. However, the decoder must still generate the full original sequence, and the encoder-decoder architecture is more expensive than encoder-only or decoder-only models of equivalent capacity. For pure understanding tasks, BERT-style encoders may be more efficient. For pure generation tasks, GPT-style decoders may be preferable. Denoising models like BART occupy a middle ground that excels when both capabilities are needed.

Key practical considerations include:

-

Corruption choice matters: Different corruptions suit different downstream tasks. Text infilling helps summarization but may not help classification. Empirical tuning is often necessary.

-

Sentence boundaries required: Sentence permutation requires reliable sentence segmentation. For domains with unusual punctuation or formatting, this corruption may introduce artifacts.

-

Length changes complicate batching: Token deletion and infilling change sequence lengths, requiring dynamic padding or variable-length batching infrastructure.

Despite these limitations, denoising objectives work well in practice. BART achieved state-of-the-art results on summarization, translation, and question answering when released. The insight that diverse corruptions produce versatile models has influenced subsequent work like T5, mBART, and PEGASUS. Models trained with denoising objectives often transfer better to generation tasks than MLM-only models, while maintaining competitive understanding performance.

Key Parameters

The corruption functions implemented in this chapter share several configurable parameters that control the difficulty and nature of the denoising task:

-

deletion_prob (default: 0.15): Probability of deleting each token in token deletion. Higher values remove more content but may destroy too much context for reliable reconstruction. The 15% rate matches BERT's masking rate, though BART's final model uses text infilling rather than pure deletion.

-

shuffle_distance (default: 3): Maximum positions a token can move during shuffling. Smaller values (1-2) test local word order, while larger values (5+) test sentence-level syntax understanding. The noise-based algorithm ensures tokens typically move less than the maximum.

-

mask_prob (default: 0.30 for BART): Fraction of tokens to include in masked spans during text infilling. Higher than BERT's 15% because each mask can represent multiple tokens, making the objective more efficient.

-

mean_span_length (default: 3): Average number of tokens per masked span. Sampled from a geometric distribution, meaning most spans are short (1-2 tokens) with occasional longer spans. Controls the balance between token-level and phrase-level learning.

-

permute_sentences (default: True): Whether to apply sentence permutation before text infilling. Combining both corruptions teaches both local and global structure. Can be disabled for single-sentence inputs.

-

mask_token (default: "[MASK]"): Placeholder token inserted for masked spans. Unlike span corruption which uses unique sentinels for each span, text infilling uses the same token for all spans, requiring the model to infer span boundaries.

Summary

Denoising objectives train models to reconstruct original text from corrupted inputs. This chapter covered the major corruption strategies and their effects:

-

Token deletion removes tokens entirely, forcing the model to identify missing content and insert it at the correct positions

-

Token shuffling permutes word order within a local window, teaching the model syntax and word order constraints

-

Sentence permutation reorders sentences within documents, developing understanding of discourse structure and coherence

-

Document rotation moves content from the beginning to the end, training sensitivity to document boundaries and openings

-

Text infilling replaces spans with single mask tokens, combining content prediction with length prediction for flexible generation

-

BART-style combination uses text infilling plus sentence permutation to train models that excel at both understanding and generation

The choice of corruption strategy depends on the target application. Text infilling suits generation tasks, while combining multiple corruptions produces more robust general-purpose models. The encoder-decoder architecture of denoising models naturally supports both bidirectional encoding for understanding and autoregressive decoding for generation.

The next part of the book explores BERT and its variants, examining how encoder-only architectures apply masked language modeling to build powerful understanding models.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about denoising objectives and BART's corruption strategies.

Comments