Master BERT representation extraction with [CLS] token usage, layer selection strategies, pooling methods, and the frozen vs fine-tuned trade-off. Learn when to use BERT as a feature extractor and how to choose the right approach for your task.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

BERT Representations

You've trained or downloaded a BERT model. Now what? The raw transformer produces 12 or 24 layers of hidden states, each containing one 768-dimensional vector per token. That's a lot of numbers. How do you turn them into something useful for your downstream task?

This chapter tackles the representation extraction problem. We'll explore the [CLS] token, why it works for some tasks and fails for others, and which layers contain the most useful information. We'll compare pooling strategies, examine when to freeze representations versus fine-tune, and build intuition for choosing the right approach. By the end, you'll know how to extract meaningful representations from BERT for classification, similarity, retrieval, and beyond.

The CLS Token: A Sentence in a Vector

BERT prepends a special [CLS] token to every input sequence. After passing through all transformer layers, this token's final hidden state is intended to represent the entire sequence. But why does shoving extra information into position zero work at all?

The key is self-attention. Every layer allows [CLS] to attend to all other tokens. Over 12 layers, information from the entire sequence flows into this position. The model learns during pre-training, through the Next Sentence Prediction task, to aggregate sentence-level meaning at [CLS].

The hidden state of the [CLS] token after the final transformer layer. During BERT pre-training, this representation is used for the Next Sentence Prediction objective, which encourages it to capture sentence-level semantics useful for binary classification.

Let's extract the [CLS] representation from a pre-trained BERT model.

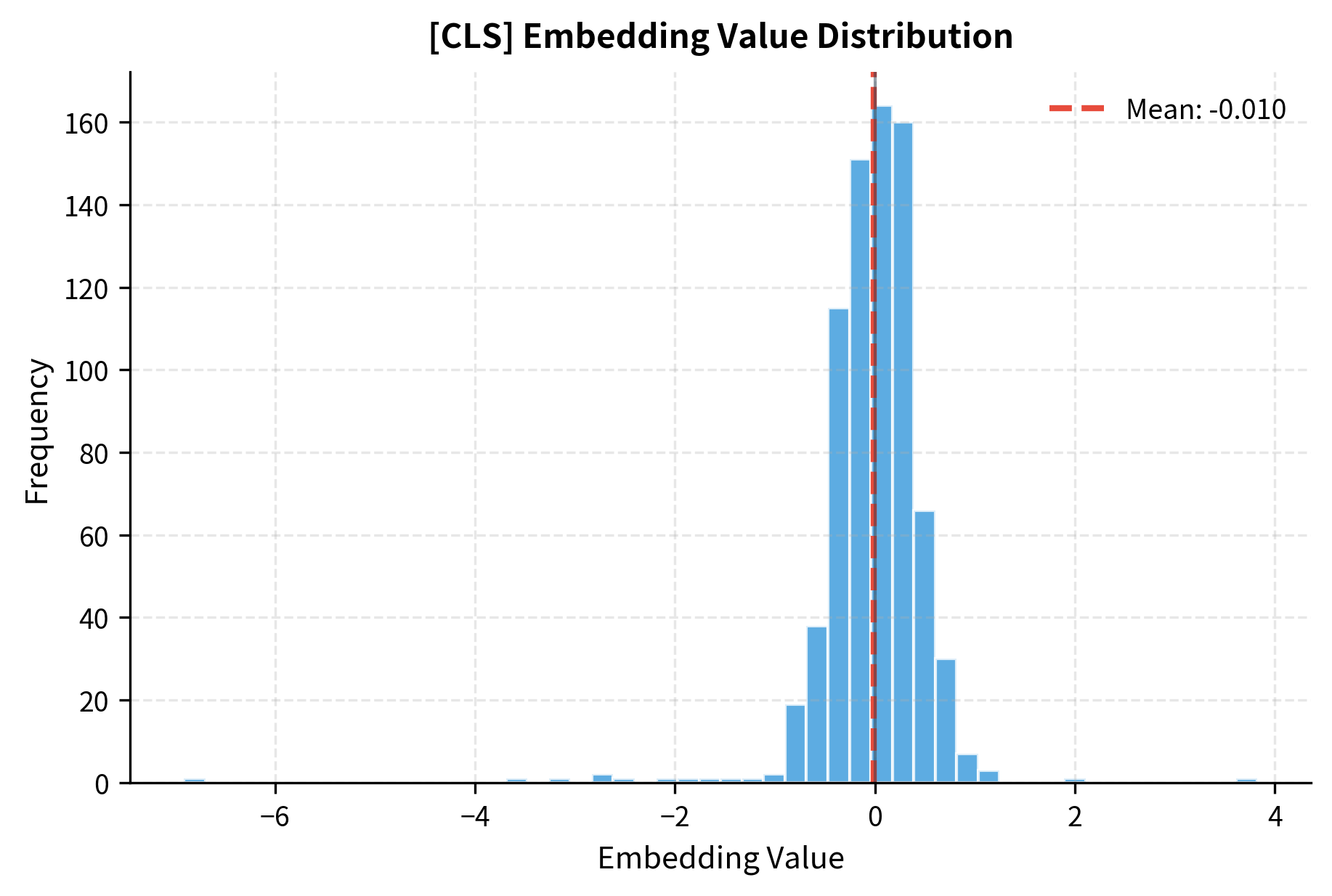

The [CLS] vector is 768-dimensional for BERT-base. The values are roughly centered around zero with moderate variance, typical of layer-normalized transformer outputs. This single vector supposedly captures everything about our sentence.

The histogram reveals that most embedding dimensions have values between -0.5 and 0.5, with a roughly symmetric distribution. This structure emerges from BERT's layer normalization, which ensures stable training by keeping activations in a controlled range.

When CLS Works

The [CLS] representation works well for tasks that mirror BERT's pre-training objectives. Classification tasks, especially binary ones, align naturally with how [CLS] was trained through NSP.

Even without fine-tuning, the [CLS] representations show some clustering by sentiment. Positive texts are more similar to each other than to negative texts. This separation, while modest, demonstrates that [CLS] captures semantic information relevant to classification.

When CLS Fails

The [CLS] token has a critical limitation: it was trained for NSP, not for general semantic similarity. For tasks like semantic search or sentence similarity, raw [CLS] embeddings perform surprisingly poorly.

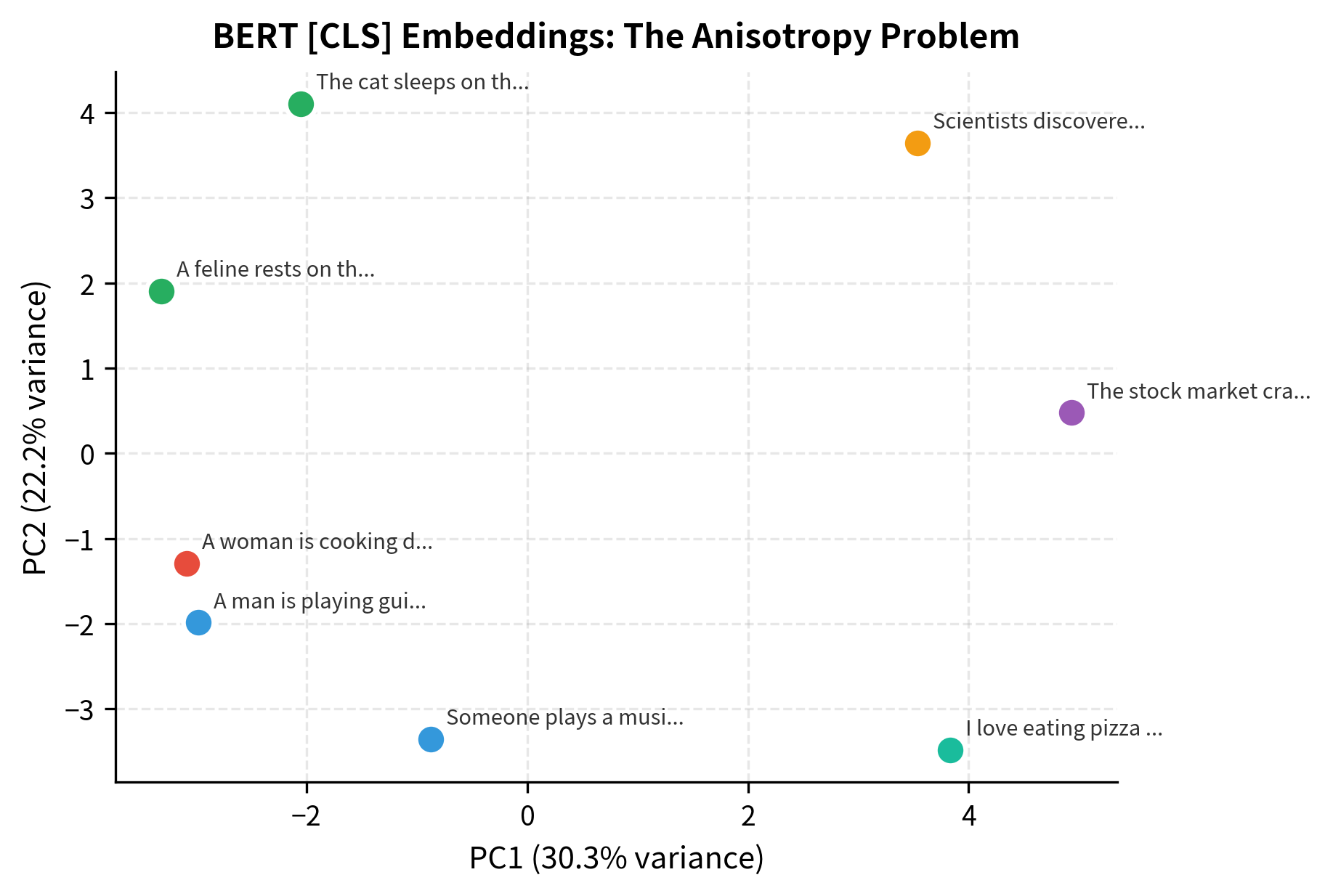

The similarities are surprisingly high across the board, even for semantically unrelated sentences. This phenomenon, sometimes called the "anisotropy problem," occurs because BERT's [CLS] representations cluster in a narrow cone of the embedding space. All sentences end up relatively similar to each other, making it hard to distinguish truly related content from unrelated content.

The PCA projection reveals the problem clearly: sentences about music, cats, finance, and food all occupy a tiny region of the embedding space. The first two principal components capture only a small fraction of the total variance, indicating that most variation happens along directions that don't distinguish semantic content well.

This is why models like Sentence-BERT (SBERT) exist. They fine-tune BERT specifically for sentence similarity, producing representations where cosine similarity actually correlates with semantic relatedness.

Layer Selection: Where's the Information?

BERT doesn't produce just one representation. BERT-base has 12 transformer layers, each outputting a full sequence of hidden states. Which layer should you use?

The answer depends on your task. Different layers capture different types of linguistic information. Research has shown that:

- Lower layers (1-4) capture surface-level features like part-of-speech and simple syntax

- Middle layers (5-8) capture syntactic structures and dependencies

- Upper layers (9-12) capture task-specific and semantic information

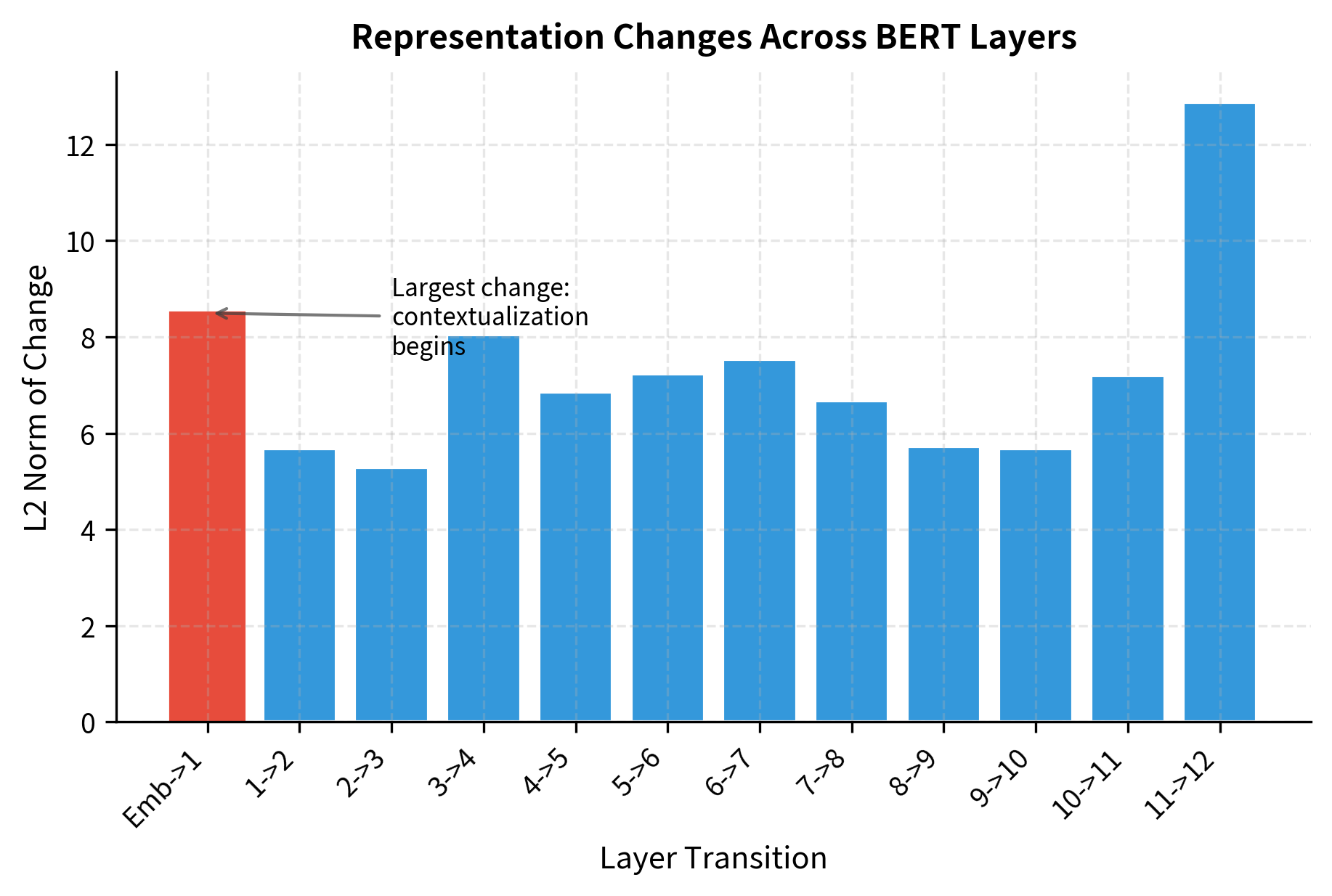

Let's visualize how representations evolve across layers.

The representation changes significantly between early layers, then stabilizes somewhat in middle and upper layers. This reflects BERT's processing: early layers rapidly transform raw token embeddings into contextualized representations, while later layers refine these representations more subtly.

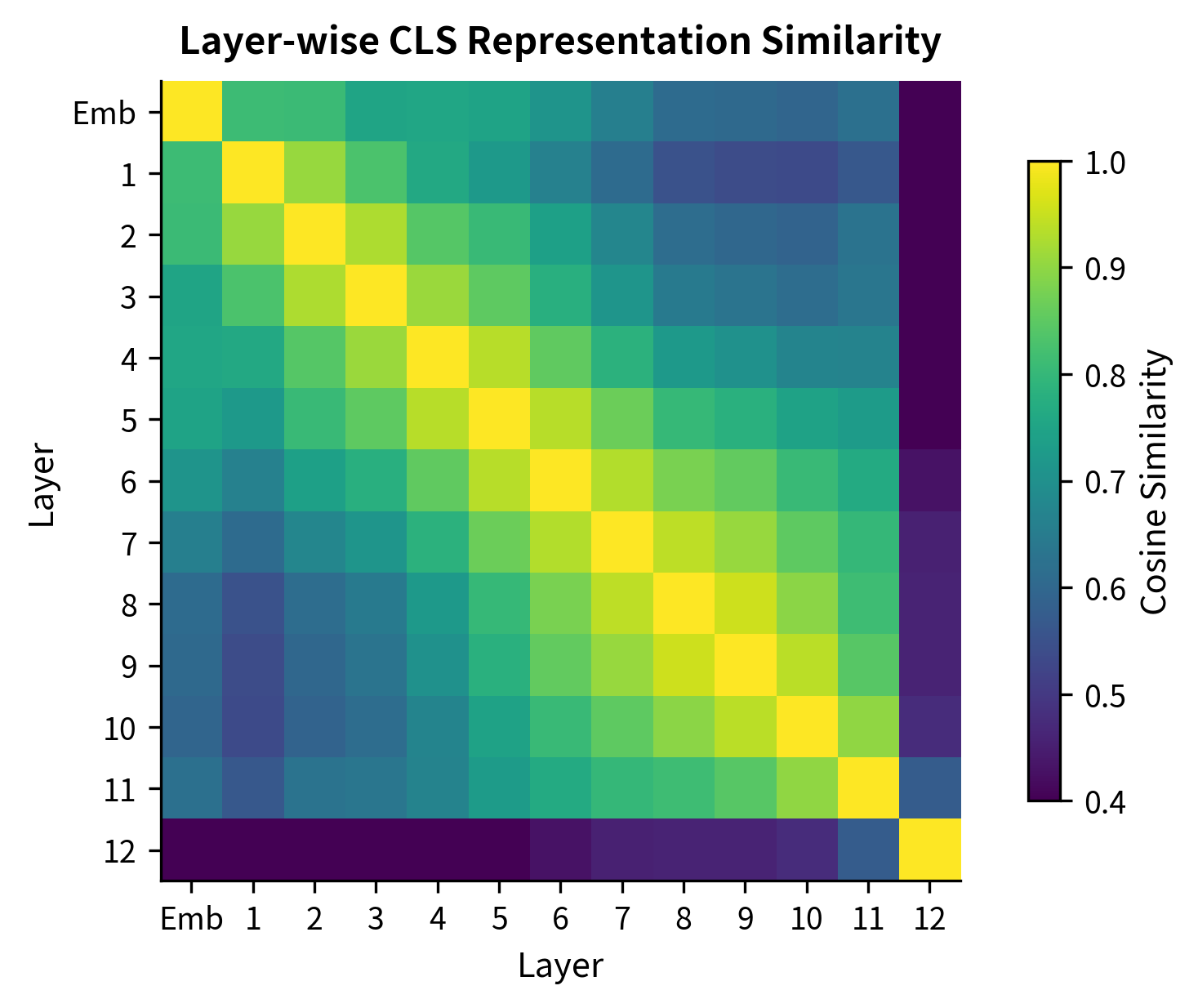

The heatmap reveals a clear pattern. Adjacent layers are highly similar, shown by the bright diagonal band. But layer 1 and layer 12 are quite different, with similarity around 0.5. The information encoded at different depths varies substantially.

Task-Specific Layer Selection

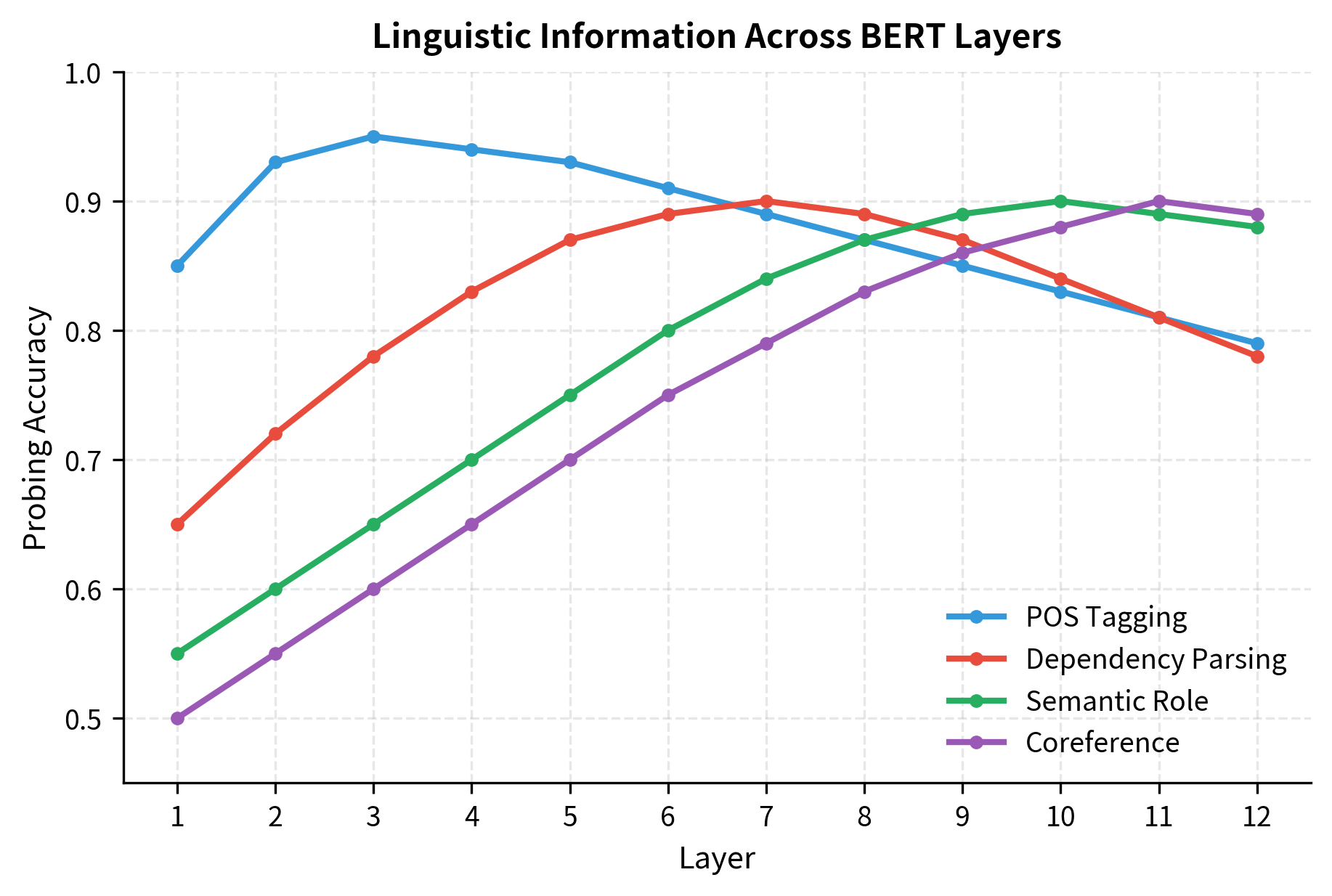

Different NLP tasks benefit from different layers. Probing experiments have systematically tested which layers encode which linguistic properties.

POS tagging peaks at layers 3-4, while coreference resolution benefits from the deepest layers. This has practical implications. If you're building a part-of-speech tagger, using the last layer might actually hurt performance. Using layer 3 or 4 could give you a better starting point.

Layer Combination Strategies

Why limit yourself to one layer? Several strategies combine information across layers.

Concatenation stacks representations from multiple layers:

Concatenation produces a larger vector (3072 dimensions for last-4 concatenation) but preserves distinct information from each layer. This is useful when different layers capture different aspects relevant to your task.

Weighted sum learns to combine layers adaptively:

The weighted sum keeps dimensionality fixed while allowing the model to learn which layers matter most. Models like ELMo pioneered this approach, and it works well when you want to fine-tune the combination weights for a specific task.

Scalar mix (from AllenNLP) is a learnable variant:

ScalarMix adds only 14 parameters (13 mixing weights plus gamma), making it efficient to learn the optimal layer combination during fine-tuning.

Pooling Strategies: Beyond CLS

The [CLS] token is one way to get a sentence representation, but it's not the only way. Pooling strategies aggregate information across all token positions.

Mean Pooling

Mean pooling averages the representations of all tokens (typically excluding special tokens).

Mean pooling gives equal weight to every token. This works well when all parts of the sentence contribute equally to the overall meaning, which is often the case for similarity tasks.

Max Pooling

Max pooling takes the maximum value across the sequence for each dimension.

Max pooling captures the strongest signals in each dimension. It can be useful when specific keywords or phrases are most important, though it tends to be more sensitive to outliers than mean pooling.

Comparing Pooling Strategies

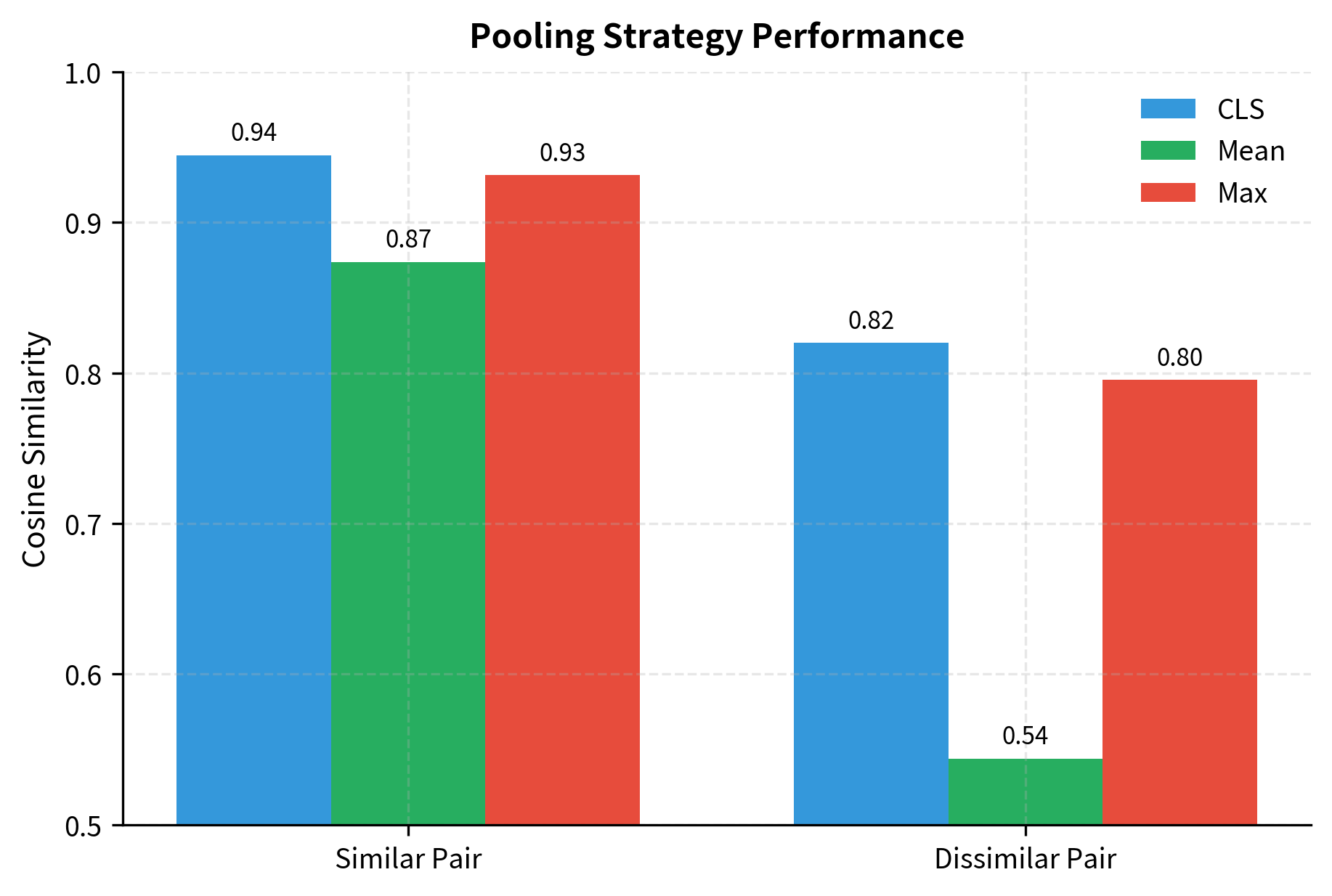

Let's compare how different pooling strategies handle the same sentences.

All strategies show the similar pair as more similar than the dissimilar pair, but the margins differ. Mean pooling often produces better separation for similarity tasks because it incorporates information from all content tokens rather than relying solely on the [CLS] position.

Attention-Weighted Pooling

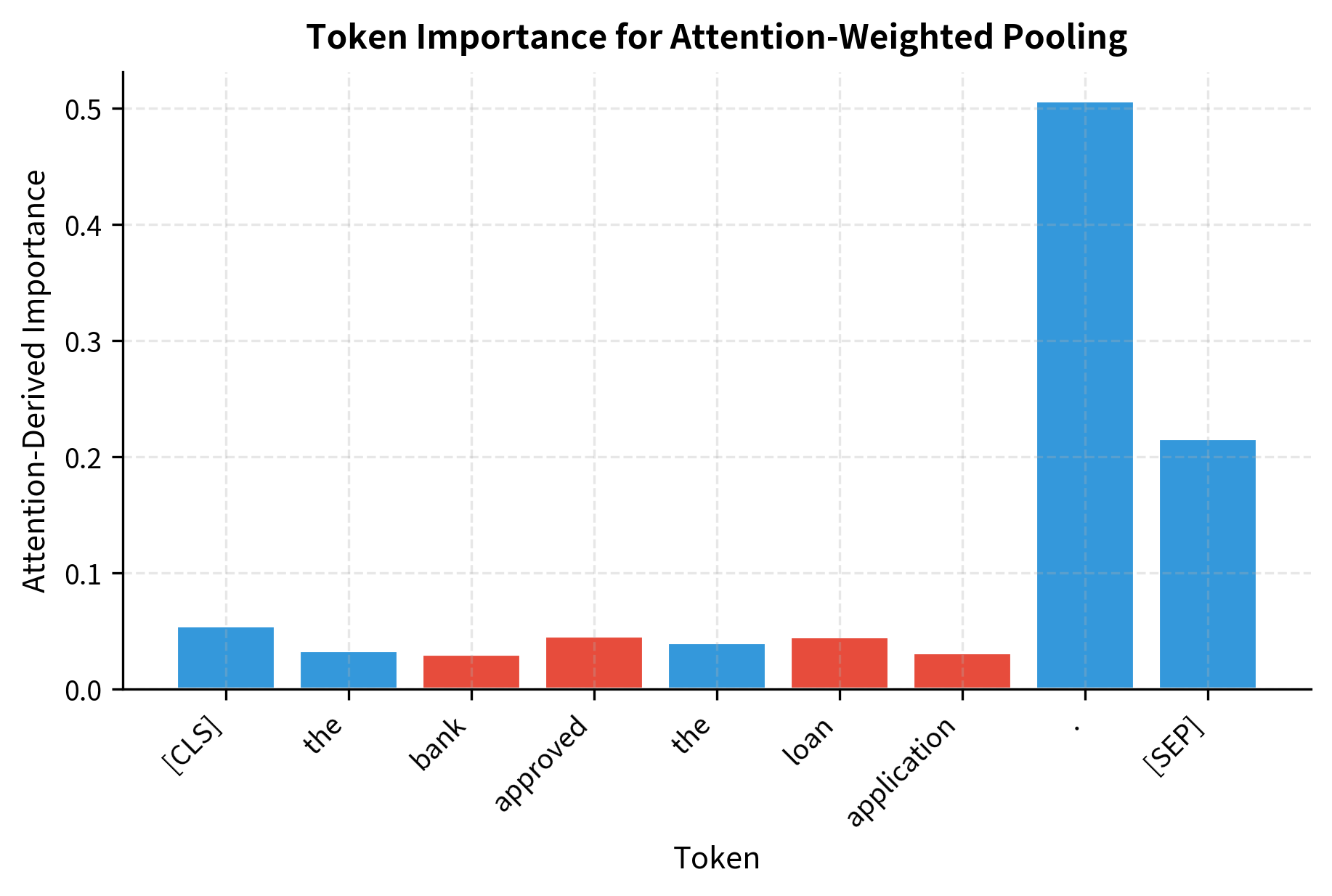

A more sophisticated approach uses the model's own attention weights to determine token importance.

Attention-weighted pooling lets the model decide which tokens matter most. Tokens that receive more attention across the sequence get higher weight in the final representation. In this example, content-bearing words like "bank", "approved", and "loan" naturally receive higher importance scores than function words like "the".

BERT as a Feature Extractor

Using BERT as a feature extractor means taking its representations as fixed inputs to a downstream model. This contrasts with fine-tuning, where BERT's weights are updated during training.

The Feature Extraction Pipeline

Feature extraction treats BERT as a frozen encoder. You pass text through BERT once, save the embeddings, and train a separate classifier on those embeddings.

These 768-dimensional features can now feed into any classifier: logistic regression, SVM, random forest, or a simple neural network.

Training a Classifier on Frozen Features

Let's train a simple classifier using extracted BERT features.

Even with a tiny dataset, the classifier achieves reasonable accuracy because BERT's pre-trained features already encode rich semantic information.

Advantages of Feature Extraction

Using BERT as a frozen feature extractor offers several practical benefits:

- Speed: Extract features once, then train classifiers instantly. You don't need GPU access for every experiment

- Simplicity: Standard ML pipelines work directly. No need for gradient-based optimization of large models

- Low resource: Train on CPU with minimal memory. Fine-tuning BERT requires significant GPU memory

- Interpretability: Downstream models can be simpler and more interpretable (e.g., logistic regression with feature importance)

Frozen vs Fine-Tuned Representations

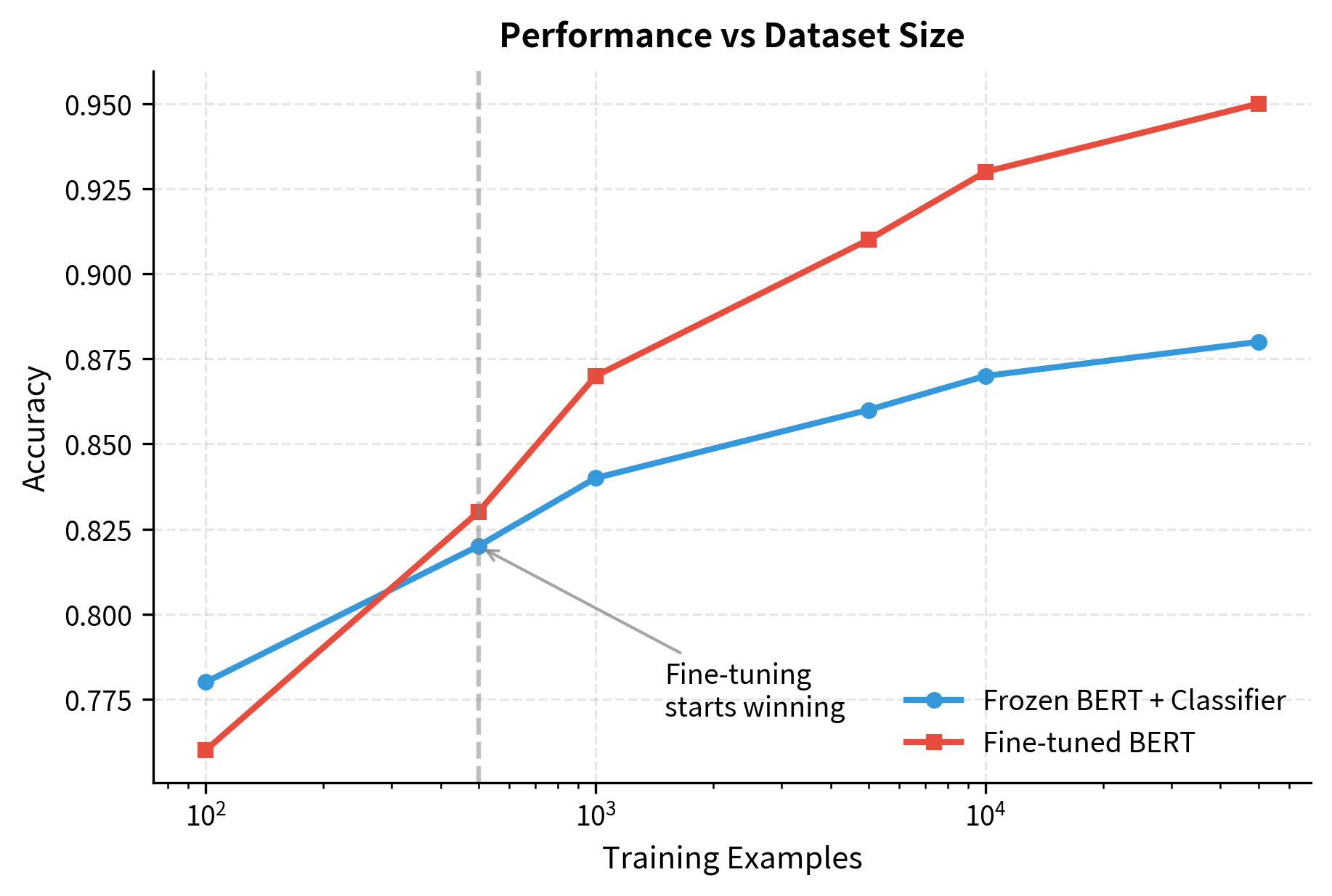

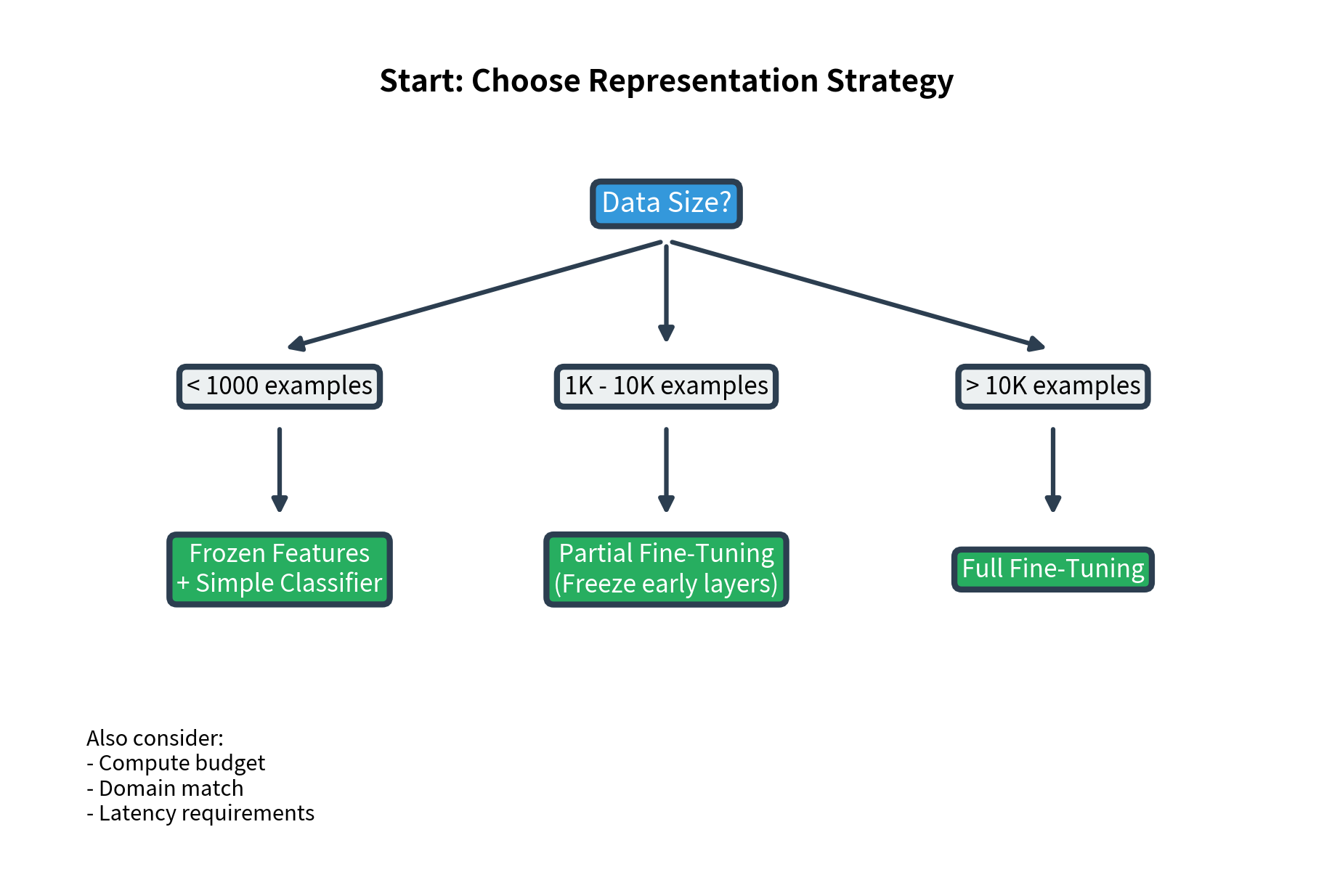

The choice between frozen features and fine-tuning depends on your data, compute budget, and task requirements. Let's examine the trade-offs.

When to Use Frozen Representations

Frozen representations work well when:

- Data is limited: With fewer than 1000 examples, fine-tuning risks overfitting. The pre-trained features are already powerful

- Compute is constrained: No GPU access, or limited training time

- Exploration phase: You're testing many different approaches quickly

- Features are reused: You'll try many classifiers on the same embeddings

With very limited data (100-500 examples), frozen features often match or beat fine-tuning. The pre-trained representations are robust, while fine-tuning on tiny datasets can cause the model to overfit or forget useful pre-trained knowledge.

When to Fine-Tune

Fine-tuning becomes advantageous when:

- Data is plentiful: Thousands of labeled examples allow the model to adapt without overfitting

- Task differs from pre-training: BERT was trained on Wikipedia and books. Your domain (legal, medical, code) may require adaptation

- Maximum performance matters: Squeezing out every percentage point of accuracy justifies the compute cost

- Representations need task-specific adjustment: The optimal features for your task may differ from generic language understanding

Partial Fine-Tuning Strategies

You don't have to choose between fully frozen and fully fine-tuned. Intermediate strategies often work well.

Freeze early layers, fine-tune later layers:

Freezing early layers preserves the general linguistic features BERT learned during pre-training. Fine-tuning later layers allows task-specific adaptation where it matters most.

Gradual unfreezing starts fully frozen and progressively unfreezes layers during training:

Gradual unfreezing lets the classifier head stabilize before the BERT layers start changing. This can lead to more stable training, especially with limited data.

Representation Quality Metrics

How do you know if frozen representations are "good enough" for your task? Several metrics can help.

Linear probe accuracy measures how well a linear classifier can use the features:

If linear probe accuracy is high, the frozen features already separate classes well. If it's low, fine-tuning might be necessary to reshape the representation space.

Practical Recommendations

Let's synthesize everything into actionable guidelines.

Choosing Your Approach

Use this decision framework:

Quick reference table:

| Scenario | Recommended Approach | Pooling | Layer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text classification, limited data | Frozen + LogReg | Mean or CLS | Last |

| Semantic similarity | Frozen or fine-tuned | Mean | Last |

| Token-level tasks (NER) | Fine-tuned | None (use all tokens) | Last |

| Syntactic probing | Frozen | Token-level | Middle (5-8) |

| Production with latency constraints | Frozen + cache | Mean | Last |

Common Pitfalls

Avoid these mistakes when working with BERT representations:

- Using raw CLS for similarity: Vanilla BERT's

[CLS]token wasn't trained for similarity. Use mean pooling or fine-tune with contrastive objectives - Always using the last layer: For some tasks, middle layers work better. Experiment with layer selection

- Ignoring the attention mask: When pooling, always mask out padding tokens to avoid noise in your representations

- Fine-tuning with tiny data: With fewer than a few hundred examples, frozen features often outperform fine-tuning

- One-size-fits-all pooling: Match pooling to your task. CLS for classification, mean for similarity, token-level for NER

Limitations and Practical Considerations

BERT representations, whether frozen or fine-tuned, have important limitations to keep in mind.

The anisotropy problem means that BERT's representation space isn't uniformly distributed. Embeddings cluster in a narrow cone, making cosine similarity less discriminative than you might expect. Methods like whitening, centering, or training with contrastive objectives (as in Sentence-BERT) can mitigate this issue.

Context length restrictions cap BERT at 512 tokens. Longer documents require chunking, which breaks cross-chunk attention. For long documents, consider hierarchical approaches: encode chunks separately, then aggregate the chunk representations.

Domain mismatch occurs when BERT's Wikipedia/BookCorpus training differs from your target domain. Legal documents, scientific papers, or social media text may benefit from domain-specific pre-training (LegalBERT, SciBERT, BERTweet) rather than vanilla BERT.

Computational cost scales with sequence length squared due to attention. For production systems processing many requests, consider distilled models (DistilBERT) or cached frozen representations rather than running inference for every query.

Despite these limitations, BERT representations remain a strong foundation for most NLP tasks. The key is matching your extraction strategy to your specific constraints and requirements.

Key Parameters

When working with BERT representations, several parameters significantly impact the quality and utility of extracted features:

- layer: Which transformer layer to extract representations from. Use

-1(last layer) for most tasks, but consider middle layers (5-8) for syntactic tasks like POS tagging or dependency parsing. The last layer contains the most task-adapted representations after fine-tuning - pooling: Strategy for aggregating token representations into sentence vectors. Options include

"cls"(use only the [CLS] token),"mean"(average all tokens), or"max"(element-wise maximum). Mean pooling typically performs better for similarity tasks - output_hidden_states: Set to

Truewhen calling the model to access all layer representations. Required for layer selection or layer combination strategies - output_attentions: Set to

Trueto access attention weights for attention-weighted pooling. Adds computational overhead - max_length: Maximum sequence length for tokenization (default 512 for BERT). Longer sequences are truncated, potentially losing important context

- num_layers_to_freeze: When partially fine-tuning, the number of early layers to keep frozen. Typically freeze 6-10 layers to preserve general linguistic knowledge while allowing task-specific adaptation in upper layers

- batch_size: Number of texts to process simultaneously during feature extraction. Larger batches are faster but require more memory. Adjust based on available GPU memory

Summary

BERT produces rich contextual representations, but extracting the right representation for your task requires careful choices.

The [CLS] token provides a convenient sentence representation, learned through next sentence prediction during pre-training. It works well for classification but poorly for semantic similarity without additional fine-tuning.

Different layers encode different linguistic properties. Lower layers capture syntax and POS information, while upper layers capture semantics and task-relevant features. Layer combination strategies like concatenation, weighted sums, or scalar mixing can capture information across the full stack.

Pooling strategies aggregate token representations into sentence vectors. Mean pooling often outperforms [CLS] for similarity tasks. Max pooling captures salient features. Attention-weighted pooling uses the model's own importance scores.

The frozen vs fine-tuned decision depends on data size, compute budget, and domain match. With limited data, frozen features plus simple classifiers often work as well as fine-tuning. With abundant data, fine-tuning unlocks higher performance but requires more compute.

Partial fine-tuning offers a middle ground: freeze early layers to preserve general linguistic knowledge while adapting upper layers to your task. Gradual unfreezing can stabilize training when adapting the full model.

Understanding these representation choices lets you get more out of BERT without blindly defaulting to fine-tuning. Sometimes the simplest approach, frozen features with mean pooling, is exactly what your task needs.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about BERT representations and how to extract them effectively.

Comments