Master cross-attention, the mechanism that bridges encoder and decoder in sequence-to-sequence transformers. Learn how queries from the decoder attend to encoder keys and values for translation and summarization.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

Cross-Attention

In the previous chapters, we explored encoder-only and decoder-only transformer architectures, each using self-attention to let tokens within a sequence attend to each other. But what happens when you need to connect two different sequences, such as when translating from English to French or summarizing a document into a shorter form? This is where cross-attention comes in, the mechanism that lets the decoder "look at" the encoder's output while generating new tokens.

Cross-attention is the bridge between encoder and decoder in sequence-to-sequence transformers. While self-attention computes relationships within a single sequence, cross-attention computes relationships between two sequences: the decoder queries the encoder's representations to extract relevant information for generating each output token.

Self-Attention vs. Cross-Attention

Self-attention and cross-attention share the same mathematical formulation: queries, keys, and values combined with scaled dot-product attention. The critical difference lies in where these components come from.

In self-attention, all three projections derive from the same sequence. Given an input matrix containing token representations, we compute queries, keys, and values as:

where:

- : the input sequence matrix, with tokens each represented as a -dimensional vector

- : the learned query projection matrix

- : the learned key projection matrix

- : the learned value projection matrix

- : the resulting query and key matrices

- : the resulting value matrix

Every token attends to every other token (and itself) within the same sequence.

In cross-attention, the queries come from one sequence while keys and values come from a different sequence. This separation is the key distinction: the decoder generates queries to ask "what do I need?" while the encoder provides keys and values to answer "here's what I have."

where:

- : the decoder's current representations (what's been generated so far)

- : the encoder's output representations (the processed source sequence)

- : the learned projection matrices for queries and keys

- : the learned projection matrix for values

- : the number of tokens in the decoder sequence (target length so far)

- : the number of tokens in the encoder sequence (source length)

- : the model dimension (size of each token's representation)

Cross-attention allows tokens in one sequence (the decoder) to attend to tokens in a different sequence (the encoder). Queries come from the decoder, while keys and values come from the encoder, enabling information to flow from the source sequence to the target sequence during generation.

This asymmetry is what makes cross-attention powerful for tasks like translation. The decoder asks questions (queries) based on what it has generated so far, and the encoder's representations provide the answers (keys and values).

The Cross-Attention Formulation

To understand cross-attention deeply, we need to think about what problem it solves. Imagine you're translating "The cat sat on the mat" into French. You've already generated "Le chat" (the cat), and now you need to produce the next word. Which part of the English sentence should you focus on? The answer is "sat," because that's the verb that follows the subject.

This is precisely what cross-attention computes: for each position in the target sequence, it determines which positions in the source sequence are most relevant, then gathers information from those positions. The mechanism needs to answer two questions simultaneously:

- Where should I look? Each decoder position needs to identify which encoder positions contain relevant information.

- What should I extract? Once the relevant positions are identified, the decoder needs to pull out the appropriate information.

The query-key-value framework elegantly separates these concerns. Queries encode what the decoder is looking for, keys encode what each encoder position offers, and values encode the actual information to transmit.

Building the Formula Step by Step

Let's construct the cross-attention formula piece by piece, understanding why each component is necessary.

Step 1: Create queries from the decoder. Each decoder position needs to express what information it's seeking. We project the decoder representations into a "query space":

where contains the decoder's current representations and is a learned projection matrix. The resulting has one row per decoder position, each encoding "what am I looking for?"

Step 2: Create keys from the encoder. Each encoder position needs to advertise what information it contains. We project the encoder output into a "key space" using a different projection:

where is the encoder output and is another learned matrix. The resulting has one row per encoder position, each encoding "here's what I offer."

Step 3: Create values from the encoder. When attention flows to an encoder position, we need to specify what information actually transfers. The value projection captures this:

where projects into a "value space." The resulting contains the content that will be aggregated.

Step 4: Compute similarity scores. Now we need to measure how well each query matches each key. The dot product is ideal for this: when two vectors point in similar directions, their dot product is large. We compute all pairwise scores with a single matrix multiplication:

The resulting score matrix has entry equal to the dot product between decoder query and encoder key . This is where the rectangular shape emerges: we're comparing queries against keys.

Step 5: Scale to prevent saturation. In high dimensions, dot products tend to have large magnitudes, which would push softmax into saturation (producing near-one-hot outputs with vanishing gradients). Dividing by normalizes the scores:

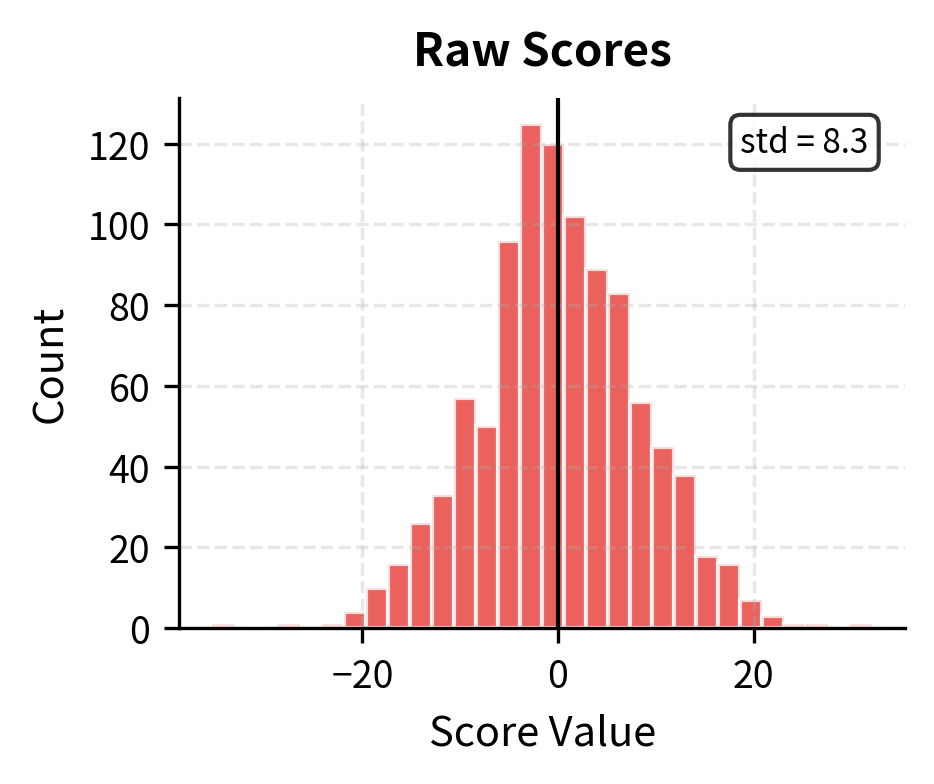

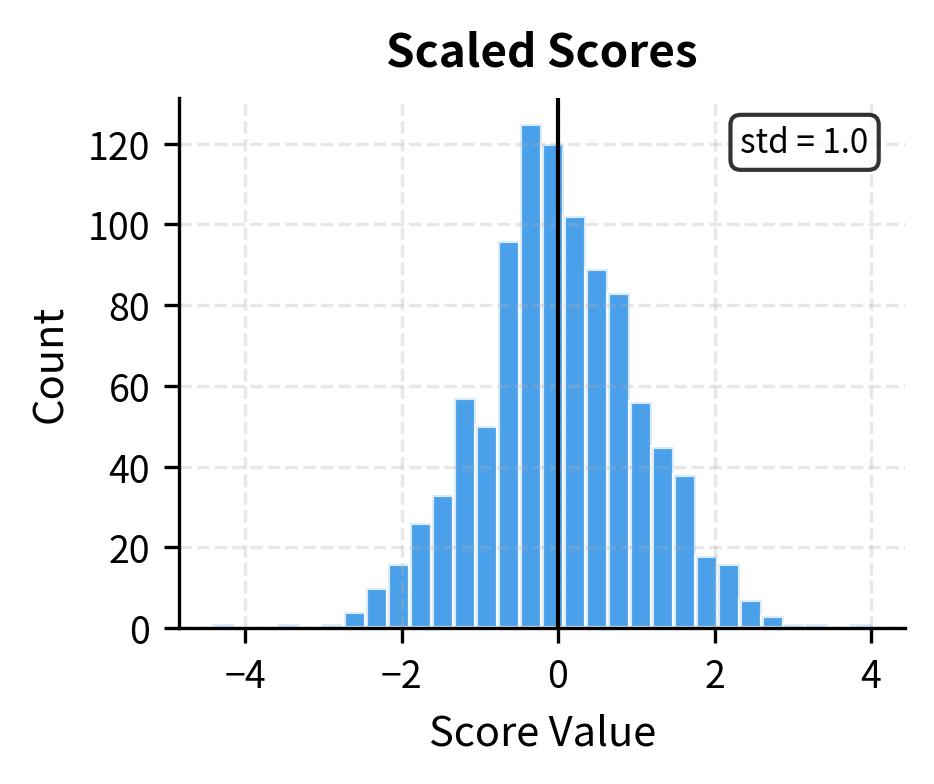

The histograms illustrate why scaling matters. With , raw dot products have a standard deviation around 8, producing scores that can easily reach or more. After scaling by , the standard deviation drops to approximately 1, keeping scores in a range where softmax produces meaningful gradients.

Step 6: Convert scores to attention weights. We apply softmax row-wise to convert each row of scores into a probability distribution over encoder positions:

Each row of sums to 1.0, representing how one decoder position distributes its attention across all encoder positions.

Step 7: Aggregate values. Finally, we use the attention weights to compute a weighted sum of encoder values for each decoder position:

The output has shape : one row per decoder position, each containing information gathered from the encoder.

The Complete Formula

Combining all steps, we arrive at the cross-attention formula:

where:

- : queries from the decoder, encoding "what information am I looking for?"

- : keys from the encoder, encoding "what information do I have to offer?"

- : values from the encoder, encoding "what content should I contribute?"

- : raw similarity scores measuring alignment between decoder queries and encoder keys

- : scaling factor that maintains healthy gradients during training

- : applied row-wise to produce probability distributions

- : query/key dimension (must match for the dot product)

- : value dimension (determines output size)

The attention weight matrix has shape , fundamentally different from self-attention's square matrix. This rectangular shape reflects the asymmetry of sequence-to-sequence tasks: we have positions that need to attend to positions, and these lengths are typically different.

Tracing Through the Computation

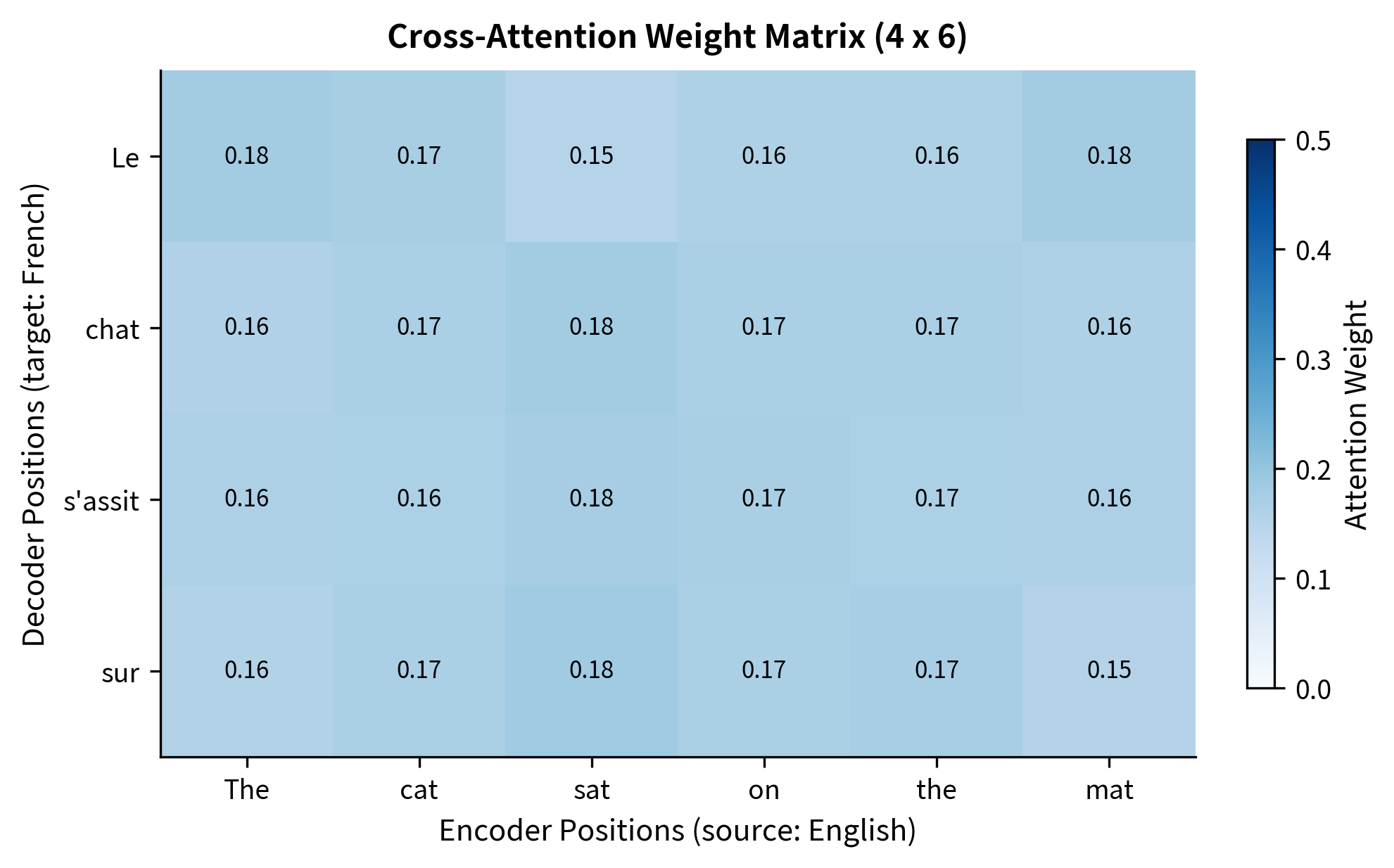

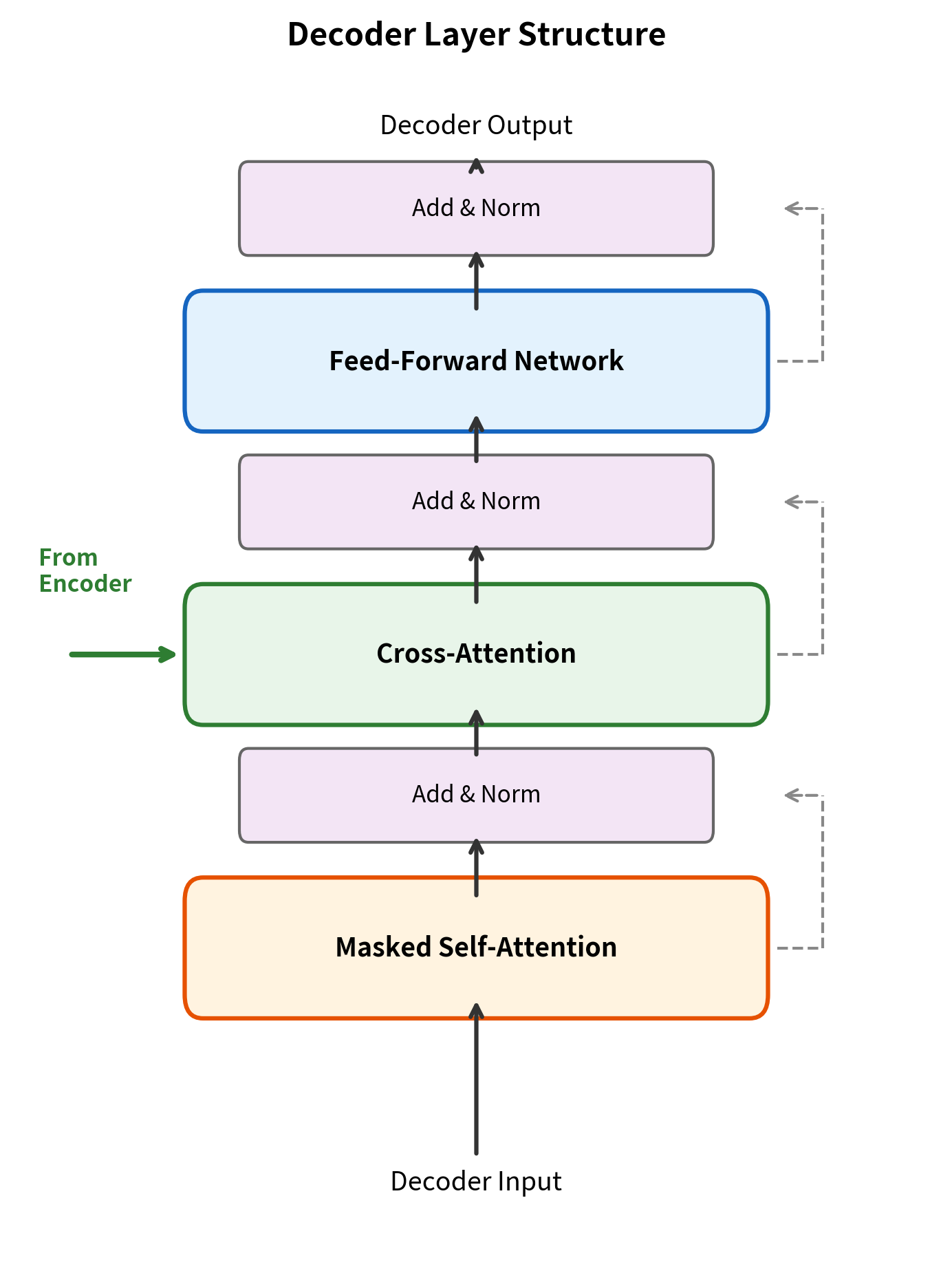

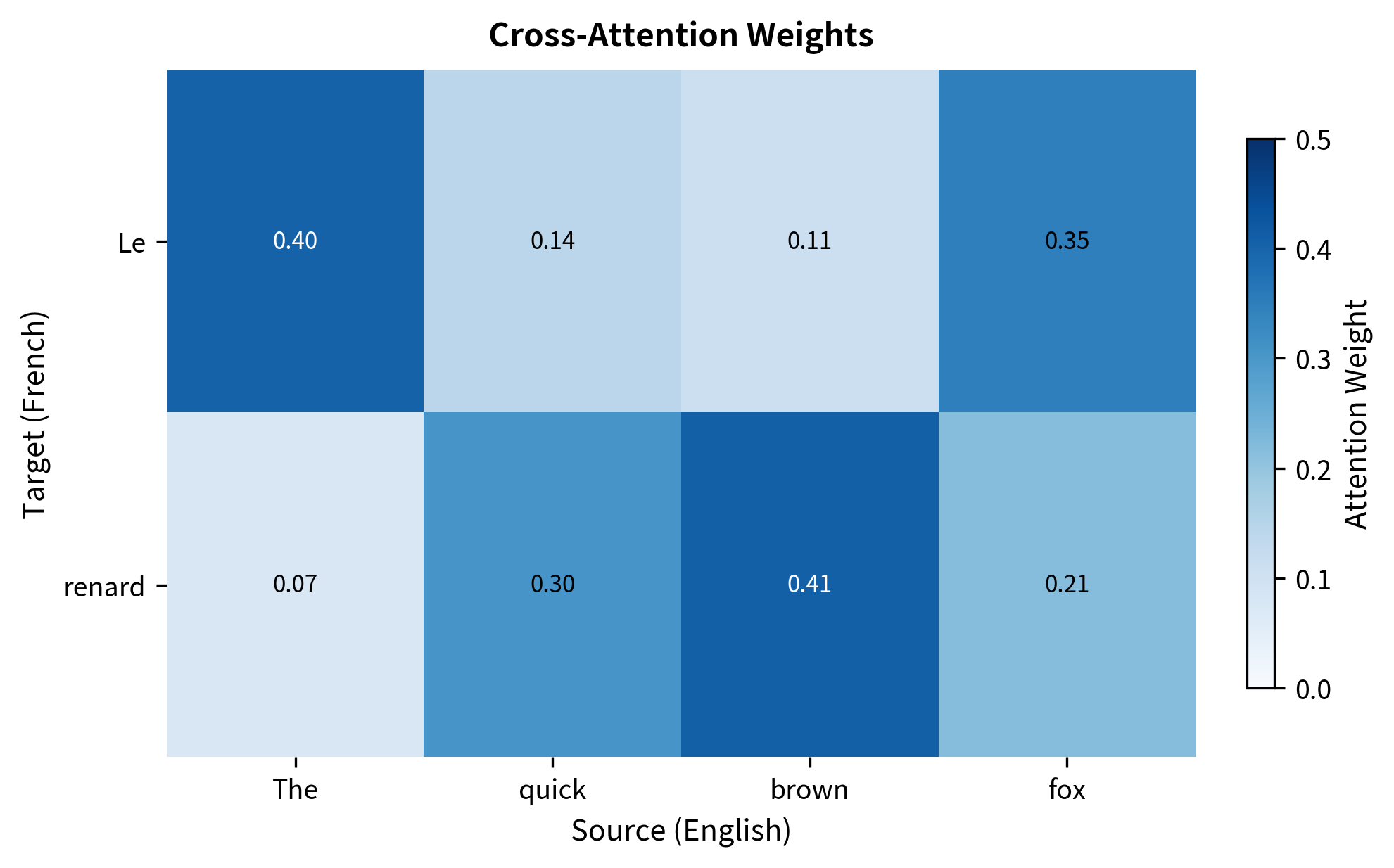

Let's make this concrete by tracing the shapes through a realistic example. We'll simulate translating a 6-word English sentence into French, where we've generated 4 words so far.

The encoder has processed all 6 source tokens, producing a matrix. The decoder has generated 4 tokens so far, giving us a state matrix. These different sequence lengths are the essence of cross-attention.

Now we project into the query, key, and value spaces:

Notice the asymmetry: has 4 rows (one per target token) while and have 6 rows (one per source token). When we compute , we multiply a matrix by a matrix, yielding a score matrix. Each of the 4 decoder positions gets a similarity score against each of the 6 encoder positions.

The output has shape , matching the decoder's sequence length but with the value dimension. Each of the 4 decoder positions now contains a weighted mixture of information from the encoder, with the weights determined by query-key similarity. This enriched representation flows to the next stage of the decoder, helping predict the next target token.

The heatmap reveals how each decoder token distributes its attention across the source sequence. Row sums equal 1.0 (each row is a probability distribution), but column sums can vary: some source tokens receive more total attention than others.

Why Queries from Decoder, Keys and Values from Encoder?

The choice of where , , and come from is not arbitrary. It reflects the fundamental asymmetry of sequence-to-sequence tasks.

Queries represent what you're looking for. At each decoder position, the model is trying to generate the next token. The query encodes "what information do I need from the source to make this prediction?" The decoder has access to its own context (previous tokens, positional information) and uses this to formulate questions.

Keys represent what's available. The encoder has processed the entire source sequence and built representations that capture its meaning. Keys advertise "here's what I know about this position in the source." The encoder output is fixed once computed, so keys remain constant throughout decoding.

Values represent what gets transmitted. When attention flows from decoder to encoder, the values determine what information actually transfers. If the decoder strongly attends to a particular encoder position, that position's value vector contributes heavily to the decoder's output.

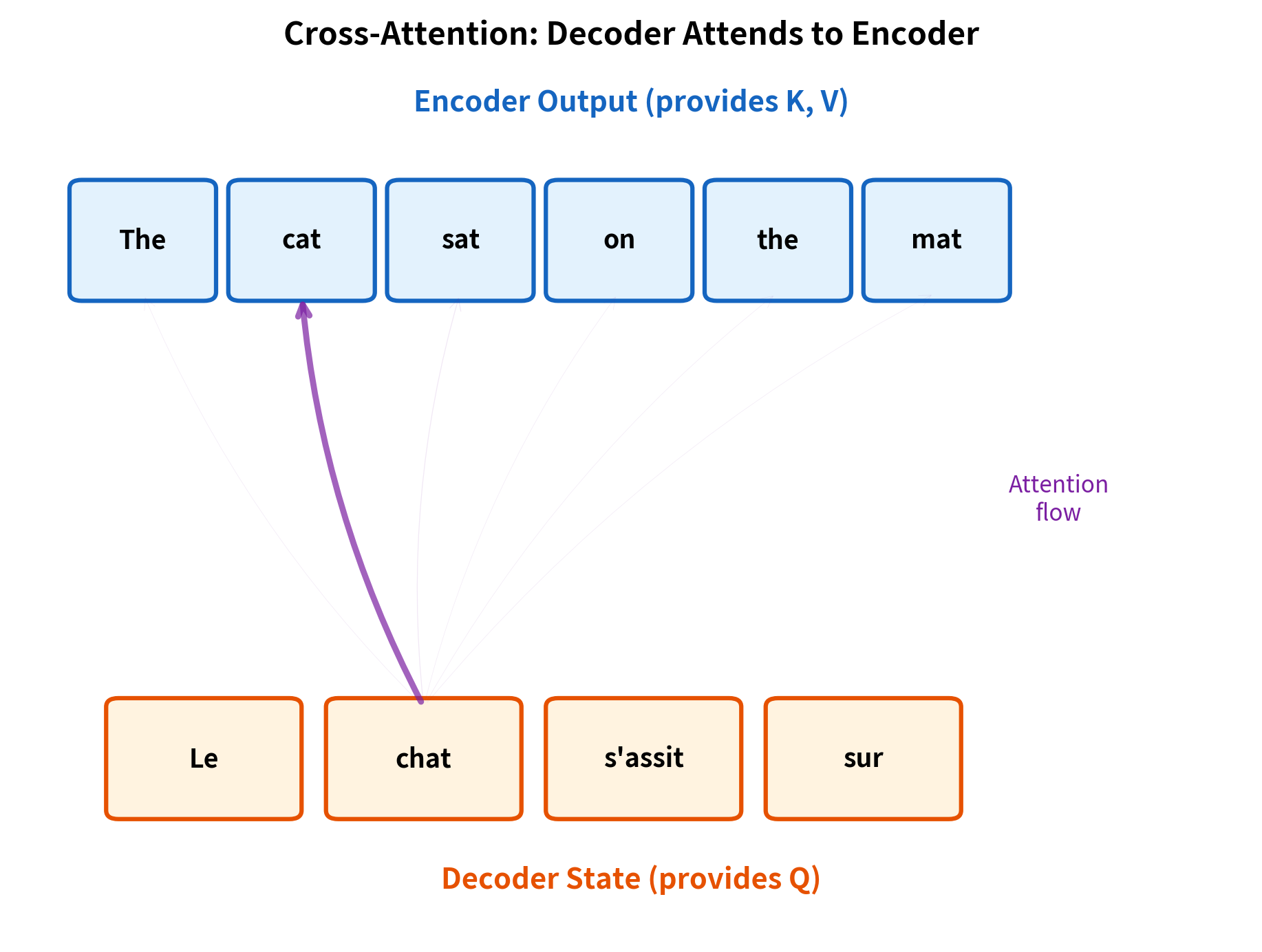

Consider translation from English to French. When generating the French word for "cat," the decoder's query might encode "I need information about an animal noun." The encoder's keys for the position containing "cat" would encode "animal, noun, subject." The high dot product between these creates a strong attention weight, and the encoder's value for "cat" (containing semantic features about cats) flows into the decoder's representation.

The visualization shows "chat" (French for "cat") attending strongly to "cat" in the encoder. This alignment emerges naturally from the learned query and key projections, which encode semantic relationships between source and target tokens.

Cross-Attention Masking

Unlike causal self-attention in decoders, cross-attention typically does not require causal masking. The decoder can attend to any position in the encoder output because the encoder sequence is fully processed before decoding begins. There's no "future information" in the encoder to hide.

However, cross-attention does require padding masking when processing batches with variable-length source sequences. If the encoder sequences have different lengths, shorter sequences are padded to match the longest. The decoder should not attend to these padding positions, which carry no meaningful information.

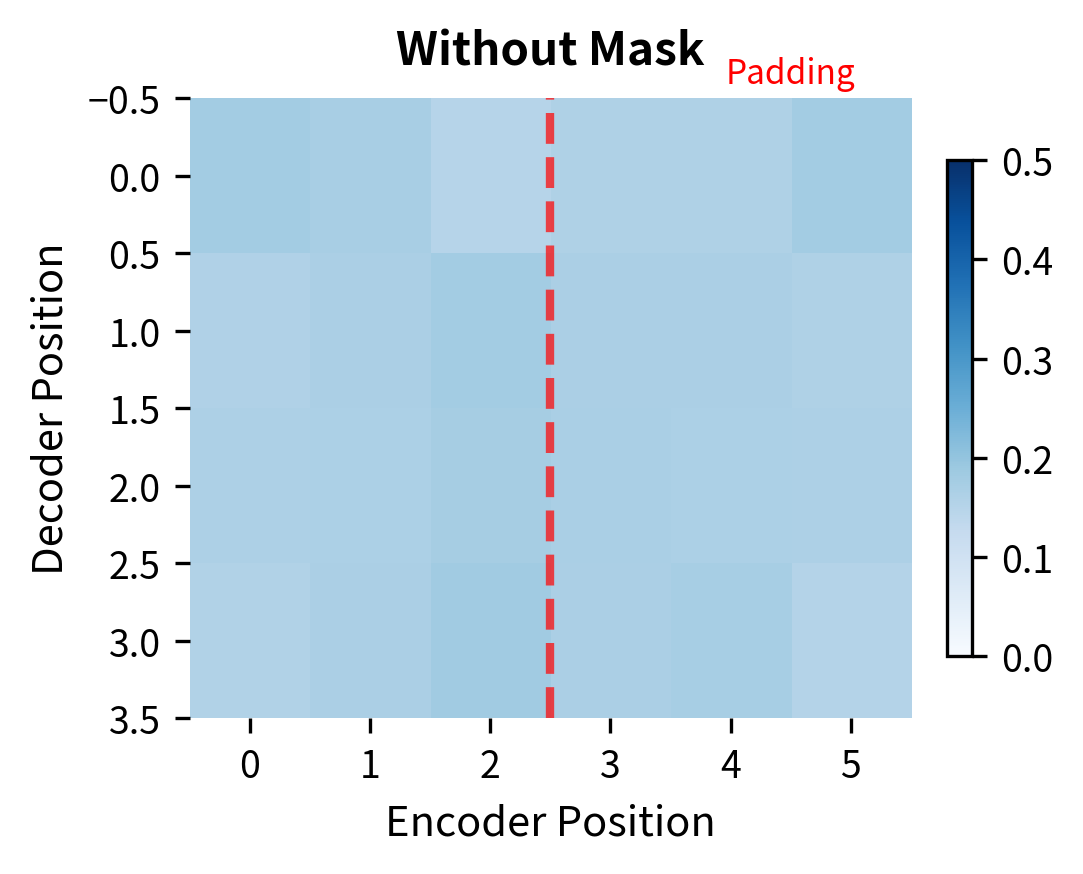

Let's see how masking affects attention:

The masking ensures that padded positions receive zero attention weight. The softmax is applied only over valid encoder positions (columns 0-2), and the probability mass distributes across those positions. This prevents the decoder from incorporating garbage information from padding tokens.

The comparison makes the effect of masking clear. Without masking, attention bleeds into padding positions, corrupting the decoder's representations with meaningless information. With masking, all attention concentrates on the valid tokens, and the model ignores padding entirely.

Placement in the Decoder

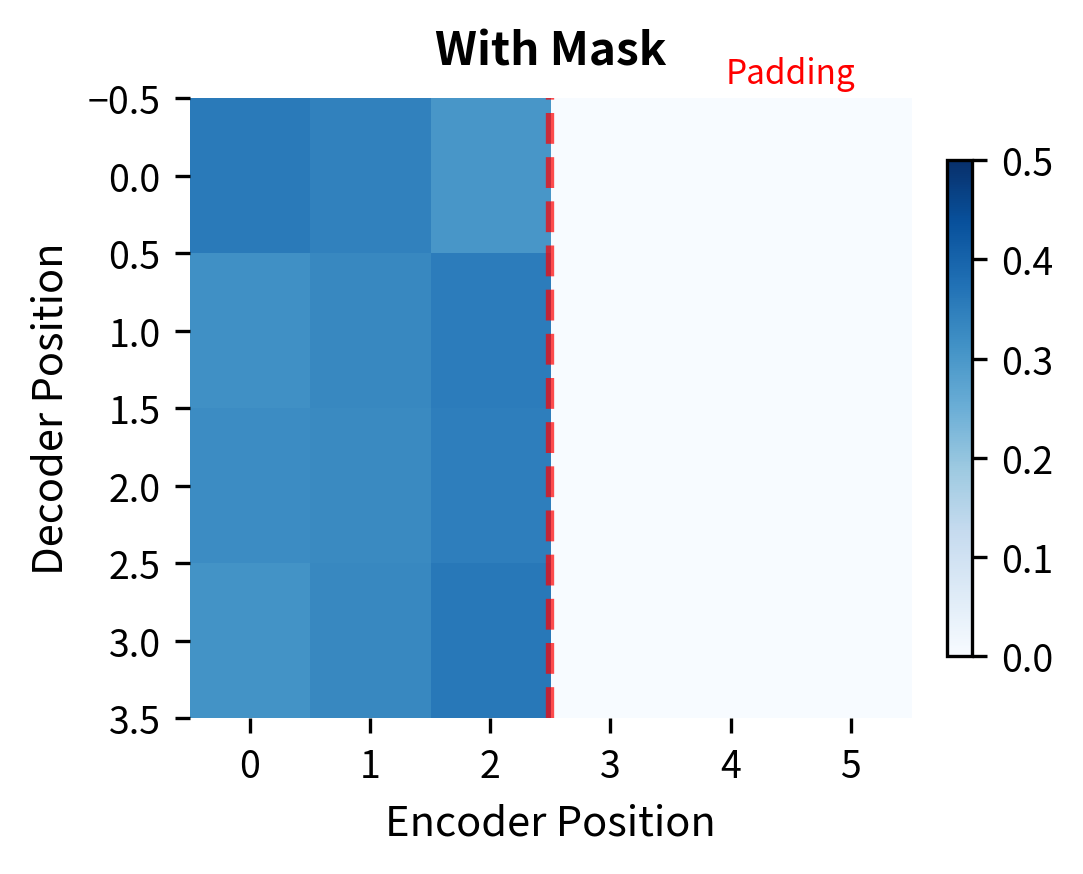

In the original transformer architecture from "Attention Is All You Need," each decoder layer contains three sub-layers:

- Masked self-attention: Decoder tokens attend to previous decoder tokens

- Cross-attention: Decoder tokens attend to encoder output

- Feed-forward network: Position-wise transformation

The order matters. Self-attention comes first, allowing each decoder position to incorporate information from previously generated tokens. Then cross-attention brings in information from the source sequence. Finally, the feed-forward network transforms the combined representation.

The cross-attention layer is the only point where information flows from encoder to decoder. The encoder output is computed once and then used identically in every decoder layer. This means the decoder doesn't need to recompute the encoder at each step, making inference efficient.

Information Flow During Generation

During autoregressive generation, the cross-attention mechanism operates as follows:

- The encoder processes the entire source sequence once, producing encoder outputs

- For each decoder step :

- The decoder's self-attention sees positions (previous outputs plus current)

- Cross-attention queries the encoder using the current decoder state

- The gathered information helps predict the next token

The encoder representations stay fixed, while the decoder's queries evolve as it generates more tokens. Early in generation, the decoder might ask broad questions about the source. Later, it might ask more specific questions as it refines its translation.

Implementation

Let's implement a complete cross-attention module following the patterns used in production transformers:

Let's test the module with a translation-like example:

Each target token distributes its attention across all source tokens. The weights indicate which parts of the source are most relevant for each target position. In a trained model, "renard" (French for "fox") would attend strongly to "fox" in the English source.

Multi-Head Cross-Attention

Just like self-attention, cross-attention benefits from multiple attention heads. Each head can learn to attend to different aspects of the source sequence: one head might focus on syntactic alignment, another on semantic similarity, a third on positional patterns.

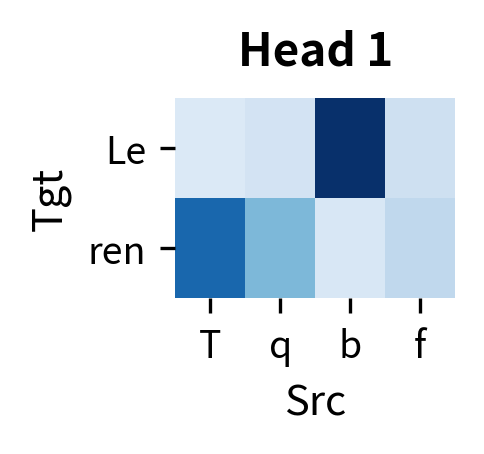

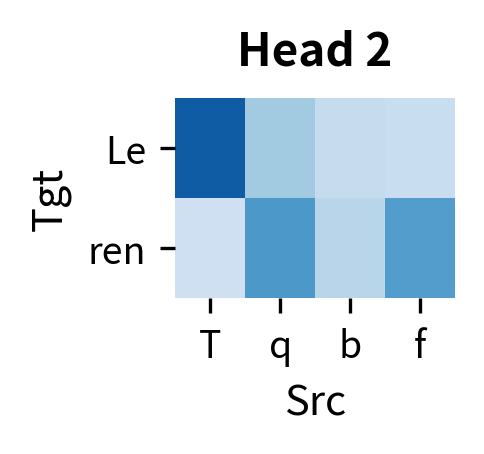

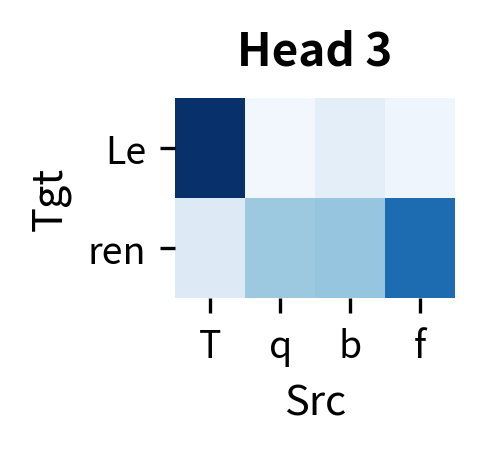

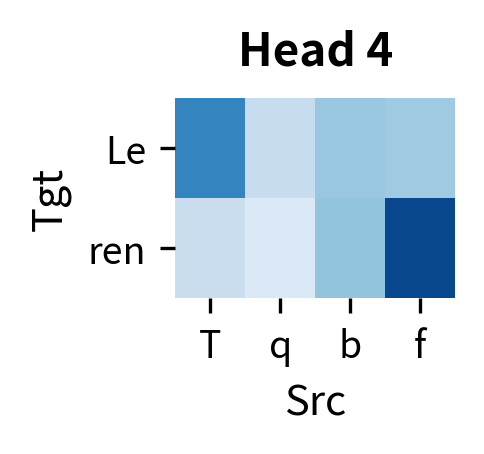

The output maintains the same shape as the decoder input (2 tokens, 32 dimensions), but now each position has gathered information from the encoder through 4 independent attention computations. The attention weights tensor has shape (4, 2, 4), meaning each of the 4 heads produces its own 2×4 attention pattern.

Each head develops its own attention pattern. In trained translation models, researchers have observed heads that focus on positional alignment (source position attends to target position ), heads that track syntactic relationships, and heads that capture semantic similarities. The diversity across heads allows the model to capture multiple aspects of source-target alignment simultaneously.

KV Caching in Cross-Attention

During autoregressive generation, cross-attention has a computational advantage over decoder self-attention. The encoder output is fixed, meaning the keys and values from the encoder can be computed once and reused for every decoding step.

This caching is particularly important for long source sequences. Without caching, generating 100 tokens from a 1000-token source would require recomputing the encoder's KV projections 100 times. With caching, we compute them once.

A Worked Example: Translation Step by Step

Let's trace through cross-attention during a translation example to see how all the pieces fit together:

In this example, "aime" (love) should ideally attend strongly to "love" in the source. While our random weights don't show this (since we haven't trained the model), a trained model would learn to align related words across languages.

The cross-attention output for each target position now contains a weighted mixture of encoder information. The next step in the decoder would combine this with the self-attention output and pass through the feed-forward network, ultimately producing logits for predicting the next token ("les").

Limitations and Impact

Cross-attention is the mechanism that makes encoder-decoder transformers work. It provides a direct, differentiable connection between source and target sequences, enabling end-to-end training of translation, summarization, and other sequence-to-sequence models.

Several characteristics of cross-attention deserve consideration when designing or deploying encoder-decoder models:

The computational complexity of cross-attention is , where is the number of decoder tokens and is the number of encoder tokens. This arises because each of the decoder positions must compute attention scores against all encoder positions. While this is typically less problematic than the self-attention in decoders (since source sequences are often shorter than the total generated output), the cost can become significant for very long source documents. Techniques like sparse cross-attention or retrieval-augmented approaches address this by attending to only a subset of encoder positions.

Cross-attention assumes the entire encoder output is available before decoding begins. This makes it unsuitable for streaming applications where source and target are produced simultaneously. For such cases, architectures like streaming transformers or monotonic attention provide alternatives.

The fixed encoder output means the decoder cannot "ask follow-up questions" that change how the source is encoded. Each decoder layer sees the same encoder representations. Some architectures address this by adding encoder layers that receive decoder feedback, though this increases complexity.

Despite these considerations, cross-attention has proven remarkably effective. It underlies the success of models like T5, BART, and mBART in translation, summarization, and question answering. The mechanism's simplicity, matching the same scaled dot-product attention used in self-attention, makes it easy to implement and optimize.

Summary

Cross-attention bridges encoder and decoder in sequence-to-sequence transformers, enabling the decoder to gather information from the encoded source sequence while generating output tokens.

Key takeaways from this chapter:

-

Q from decoder, K and V from encoder: This asymmetry defines cross-attention. Queries represent what the decoder is looking for; keys and values represent what the encoder offers.

-

Rectangular attention matrix: Unlike self-attention's square matrix, cross-attention produces a rectangular weight matrix, where is the target sequence length and is the source sequence length. Each row represents how one decoder position distributes attention across all encoder positions.

-

Padding masks, not causal masks: Cross-attention masks padding tokens in the encoder but doesn't need causal masking since the encoder sequence is fully available.

-

Fixed encoder output: The encoder is computed once, and its keys and values can be cached for efficient inference across all decoder steps.

-

Placement in decoder layers: Cross-attention appears between masked self-attention and the feed-forward network in each decoder layer, gathering source information after the decoder has processed its own context.

-

Multi-head diversity: Like self-attention, cross-attention benefits from multiple heads that can specialize in different alignment patterns.

The next chapter explores weight tying, a technique for sharing parameters between embedding layers and output projections, reducing model size while maintaining performance.

Key Parameters

When implementing cross-attention in encoder-decoder transformers, several parameters control the mechanism's behavior and capacity:

-

d_model: The model dimension, which is the size of input token representations. Both encoder outputs and decoder states should have this dimension. Common values range from 256 to 1024, with larger models using 2048 or more.

-

d_k (query/key dimension): The dimension of the projected queries and keys. This controls the capacity of the attention scoring mechanism. Typically set to

d_model // n_headsin multi-head attention, giving each head a portion of the full dimensionality. -

d_v (value dimension): The dimension of the projected values. Often equal to

d_k, but can differ. This determines the size of information transmitted when attention flows from encoder to decoder. -

n_heads: The number of parallel attention heads in multi-head cross-attention. More heads allow the model to attend to different aspects of the source sequence simultaneously. Typical values are 8, 12, or 16 heads.

-

encoder_mask: A boolean mask indicating which encoder positions are valid (True) versus padding (False). Essential for batched processing of variable-length source sequences to prevent attending to meaningless padding tokens.

-

scale factor: The scaling factor applied before softmax. This is automatically determined by

d_kand prevents attention scores from becoming too large in high dimensions, which would cause softmax to saturate.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding of cross-attention? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about connecting encoder and decoder in sequence-to-sequence transformers.

Comments