Master FlashAttention's tiled computation and online softmax algorithms. Learn GPU memory hierarchy, CUDA kernel basics, and practical PyTorch integration.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

FlashAttention Implementation

FlashAttention changes how we think about attention computation. Rather than viewing the attention formula as a mathematical specification to implement directly, FlashAttention treats it as a memory optimization problem. The algorithm produces identical outputs to standard attention but restructures the computation to minimize memory transfers between GPU memory hierarchies. Understanding how FlashAttention achieves this requires diving into GPU architecture, memory access patterns, and the algorithmic techniques that make it all work.

This chapter explores the implementation details of FlashAttention, from the fundamentals of GPU memory to practical usage in PyTorch. We'll examine CUDA kernel basics, understand why memory access patterns matter so much for performance, trace the improvements from FlashAttention to FlashAttention-2, and see how to use these techniques in your own models. By the end, you'll understand both the theoretical foundations and practical applications of what has become the de facto standard for attention computation in modern LLMs.

GPU Memory Hierarchy

Before understanding FlashAttention, you need to understand where bottlenecks actually occur on GPUs. Modern deep learning is often described as "compute-bound," but attention computation is actually "memory-bound." This distinction is crucial.

A computation is compute-bound when the limiting factor is the number of arithmetic operations the processor can perform. A computation is memory-bound when the limiting factor is how quickly data can be transferred to and from memory. Attention is memory-bound because we spend more time moving data than computing with it.

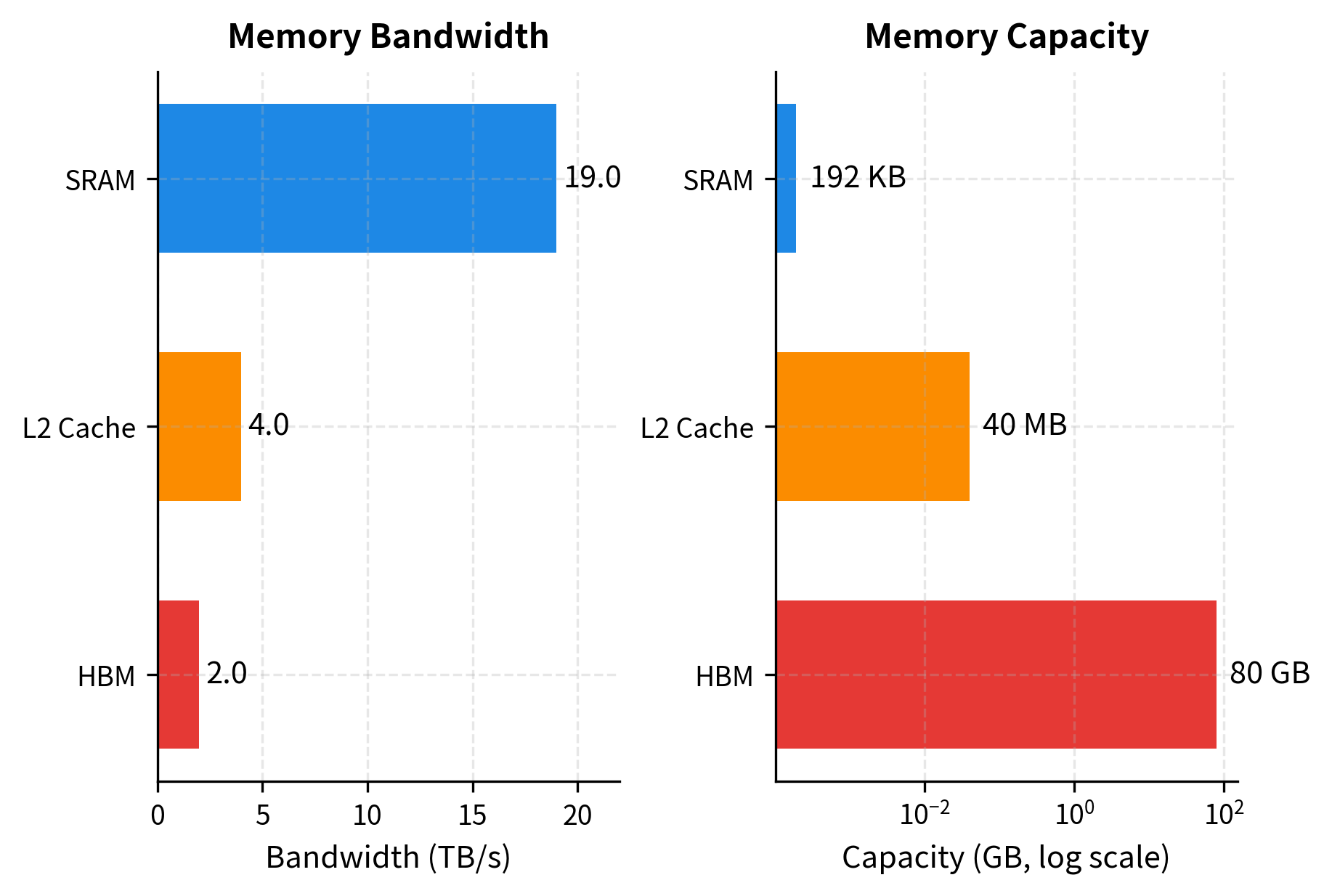

GPUs have a hierarchical memory structure with three main levels, each with different speeds and capacities:

The numbers reveal a fundamental tension. HBM (the main GPU memory where tensors live) has enormous capacity but relatively slow access. SRAM (registers and shared memory) is much faster but tiny. The speed difference is nearly 10x, while the capacity difference is over 400,000x. Standard attention computation repeatedly reads and writes to HBM, suffering the slow access speeds. FlashAttention restructures the computation to keep data in SRAM as long as possible.

Why Standard Attention is Memory-Bound

Consider what happens during standard attention computation:

- Load Q, K, V from HBM to compute

- Write S back to HBM (this is an matrix)

- Load S from HBM to compute softmax

- Write attention weights P back to HBM

- Load P and V from HBM to compute output

- Write output back to HBM

Each step involves transfers to and from the slow HBM. The matrices S and P are particularly problematic: for a sequence of 4096 tokens with 32-bit floats, each matrix is 64 MB. With 32 attention heads, that's 2 GB just for intermediate storage, per layer, per batch element.

The intermediate matrices consume over 128 MB of memory transfers, dwarfing the input and output. This is where FlashAttention intervenes: by never materializing the full matrices, it eliminates most of this memory traffic.

CUDA Kernel Basics

FlashAttention is implemented as a custom CUDA kernel, meaning it runs directly on GPU hardware with fine-grained control over memory access. Understanding a few CUDA concepts helps appreciate what FlashAttention does under the hood.

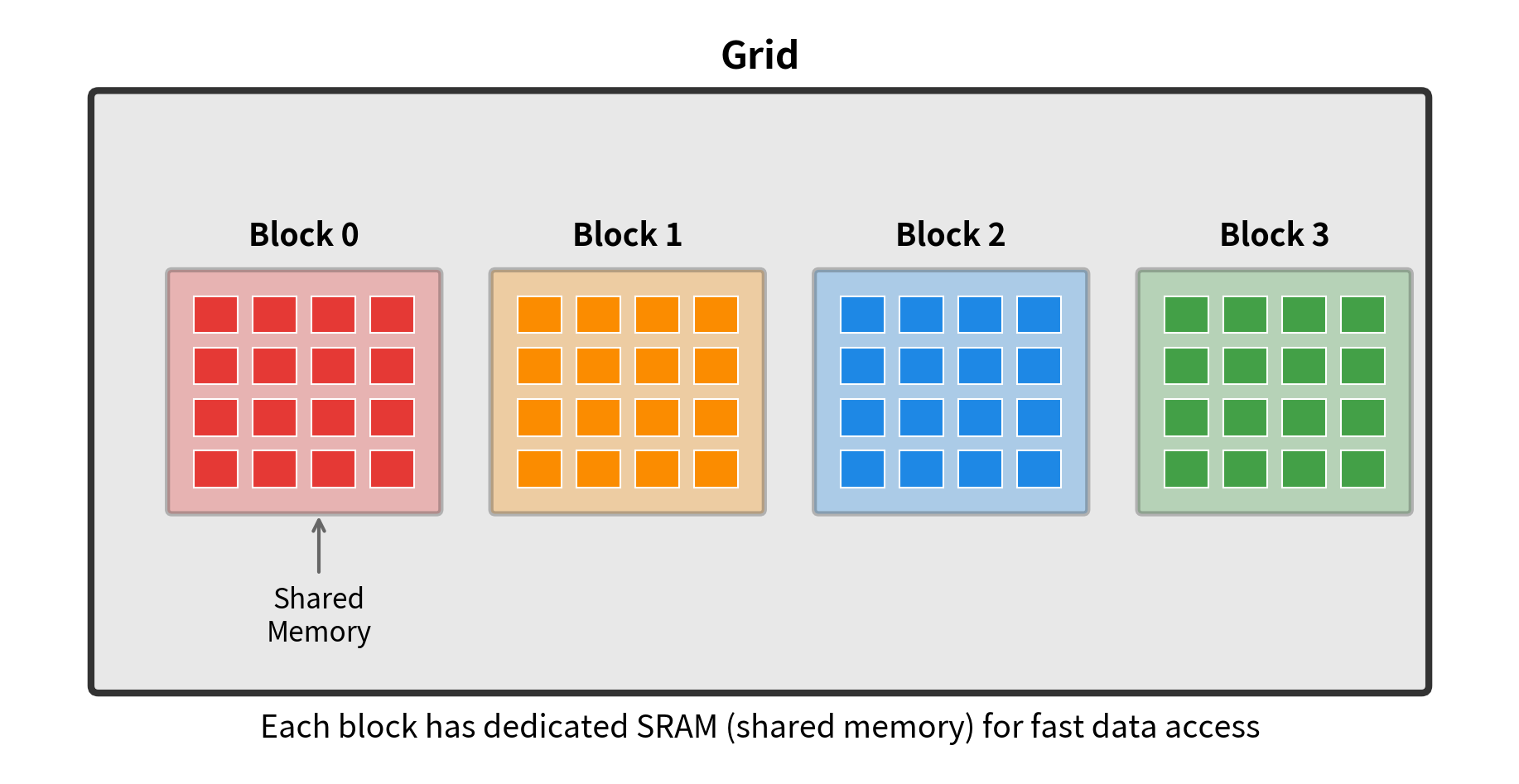

A CUDA kernel is a function that runs on the GPU across many parallel threads. Threads are organized into blocks, and blocks are organized into a grid. Each thread can access different levels of memory: registers (private to the thread), shared memory (shared within a block), and global memory (HBM, accessible by all threads).

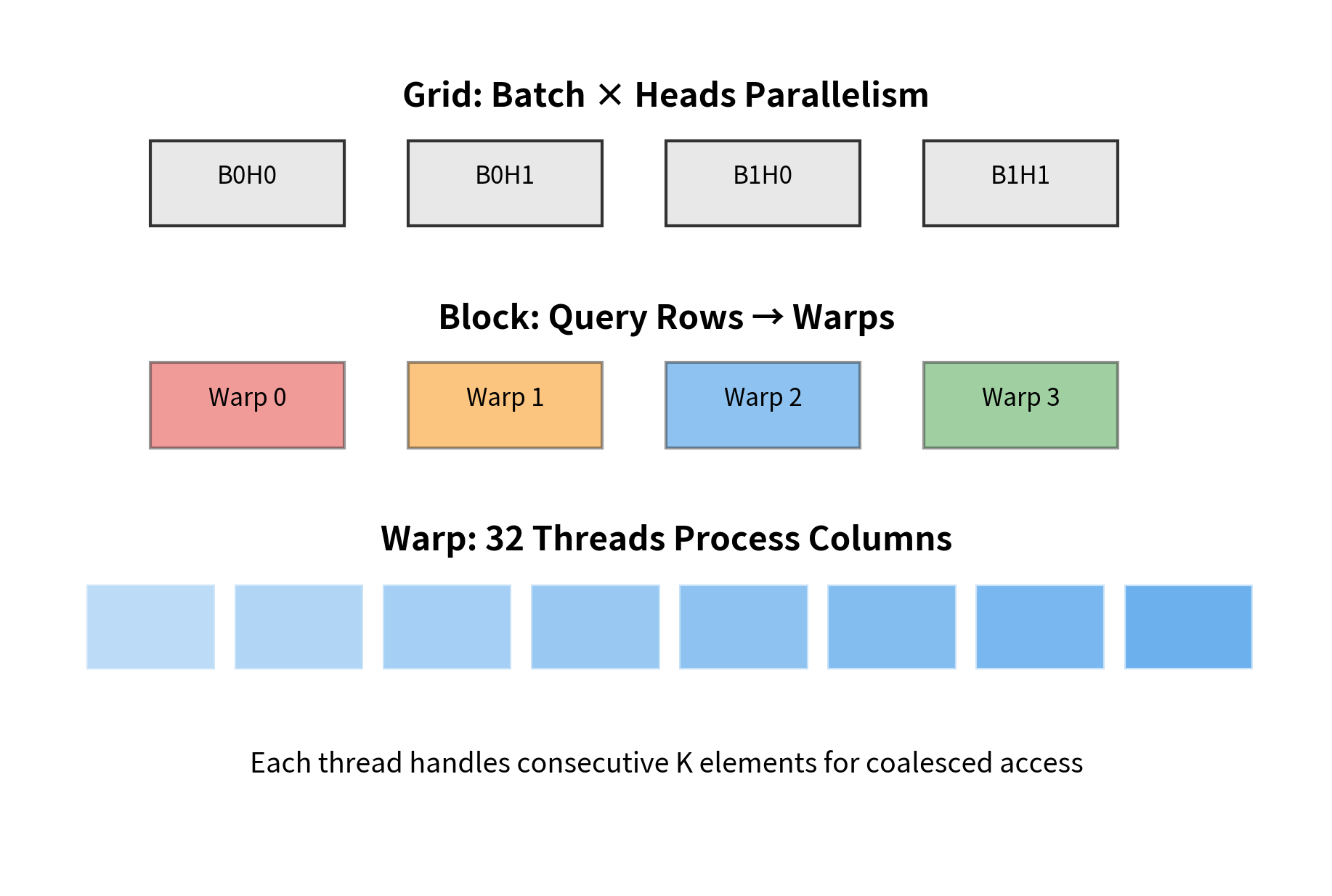

Thread Organization

CUDA organizes computation into a hierarchy. At the lowest level, individual threads execute the same code on different data. Threads are grouped into blocks, typically containing 256-1024 threads. All threads in a block can communicate through shared memory and synchronize their execution. Blocks are grouped into a grid that covers the entire problem.

For attention, a natural mapping assigns one block to compute attention for one query block against all key-value blocks. Within a block, threads collaborate to load data into shared memory, compute dot products, and accumulate results.

Memory Access Patterns

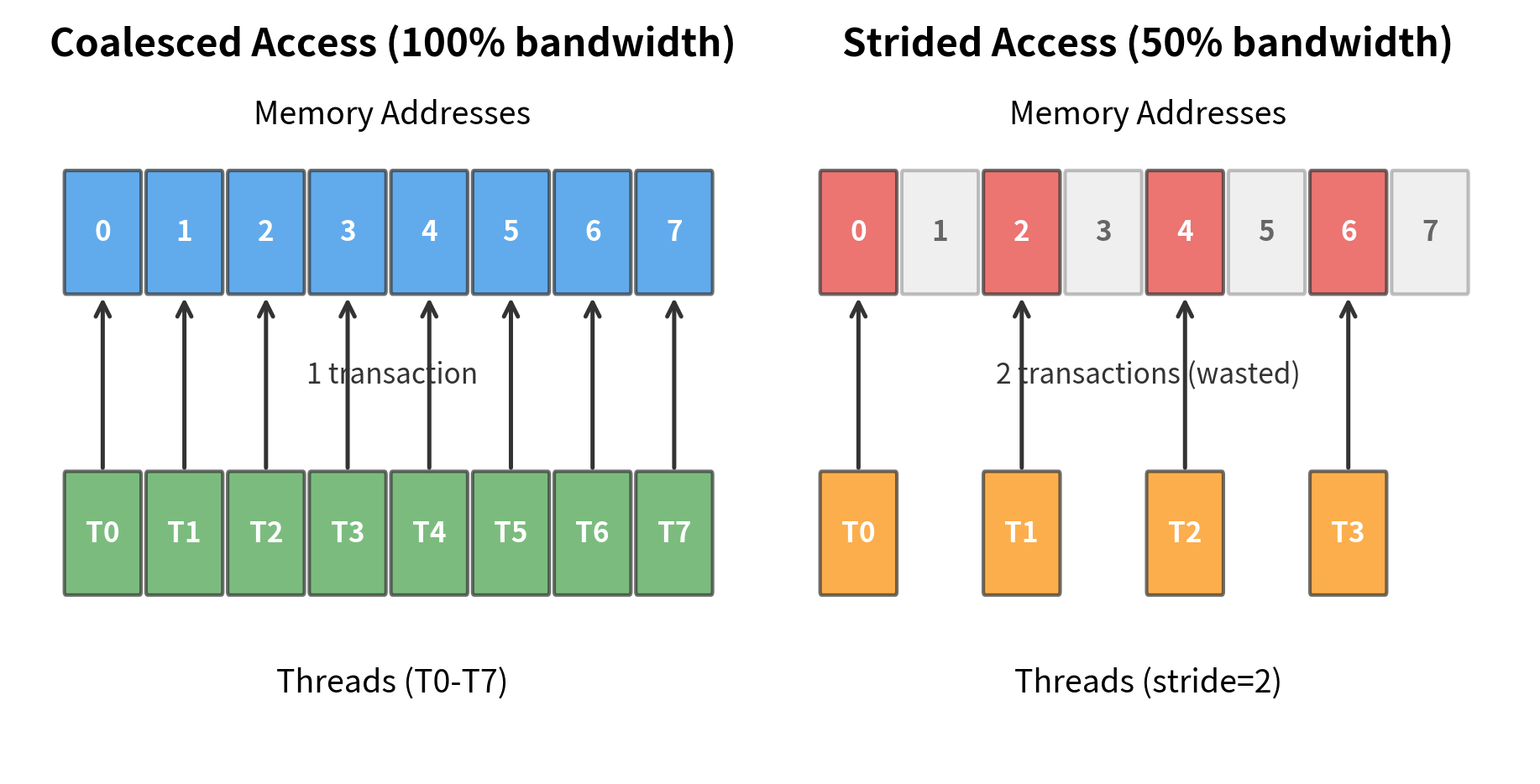

The key to GPU performance is coalesced memory access. When threads in a warp (a group of 32 threads that execute in lockstep) access consecutive memory addresses, the hardware combines these into a single efficient transaction. When threads access scattered addresses, each access becomes a separate transaction, significantly slowing execution.

FlashAttention carefully structures its memory access to achieve coalescing. When loading a block of K from HBM, consecutive threads load consecutive elements. When writing results, the same pattern applies. This attention to memory layout is one reason FlashAttention achieves such high hardware utilization.

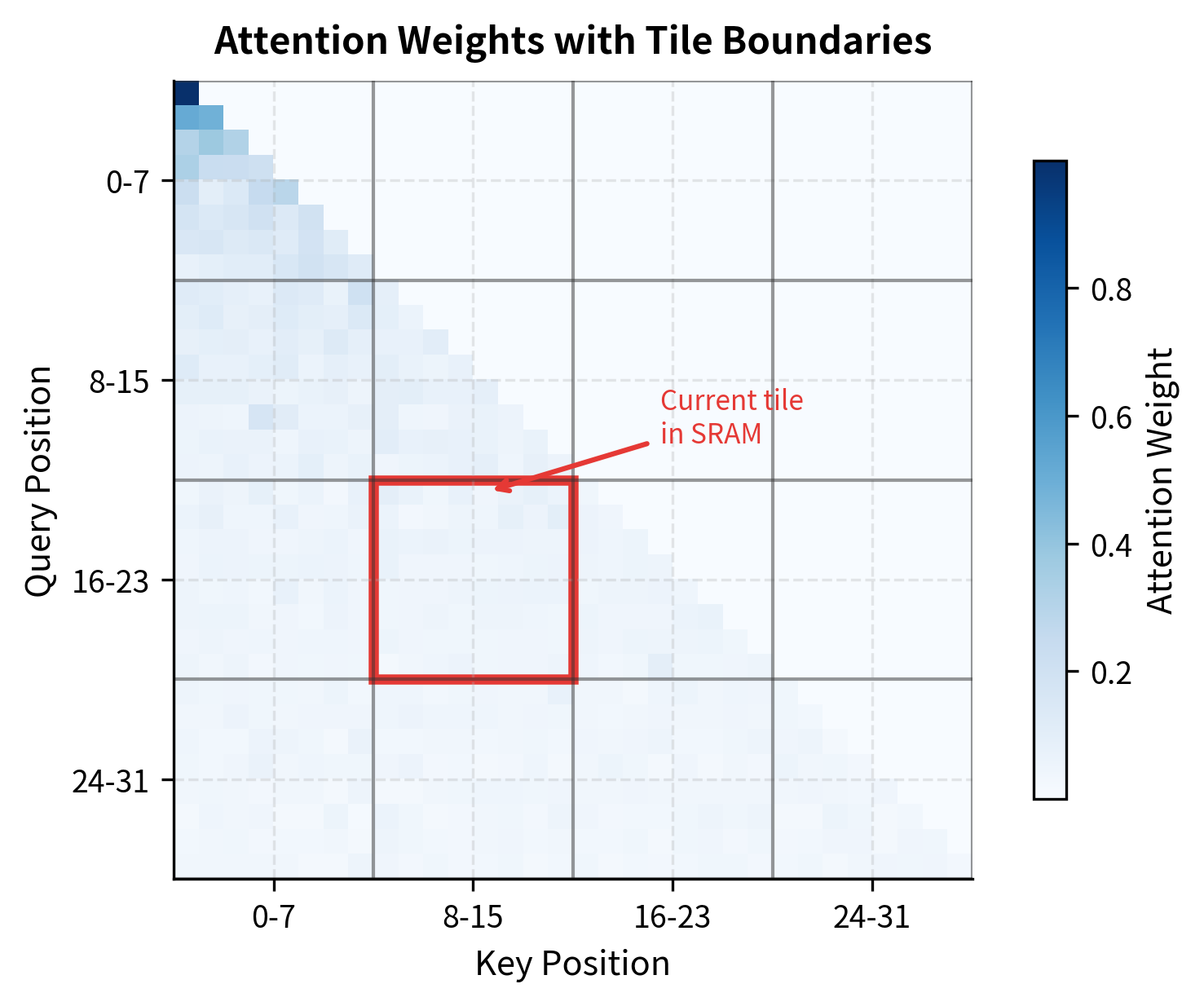

How FlashAttention Uses Tiling

We've established that standard attention is memory-bound: the algorithm spends most of its time moving data between slow HBM and fast SRAM, not actually computing. The attention matrix is the culprit, requiring multiple read-write cycles to HBM. FlashAttention's key insight starts with a simple question: what if we never stored that matrix at all?

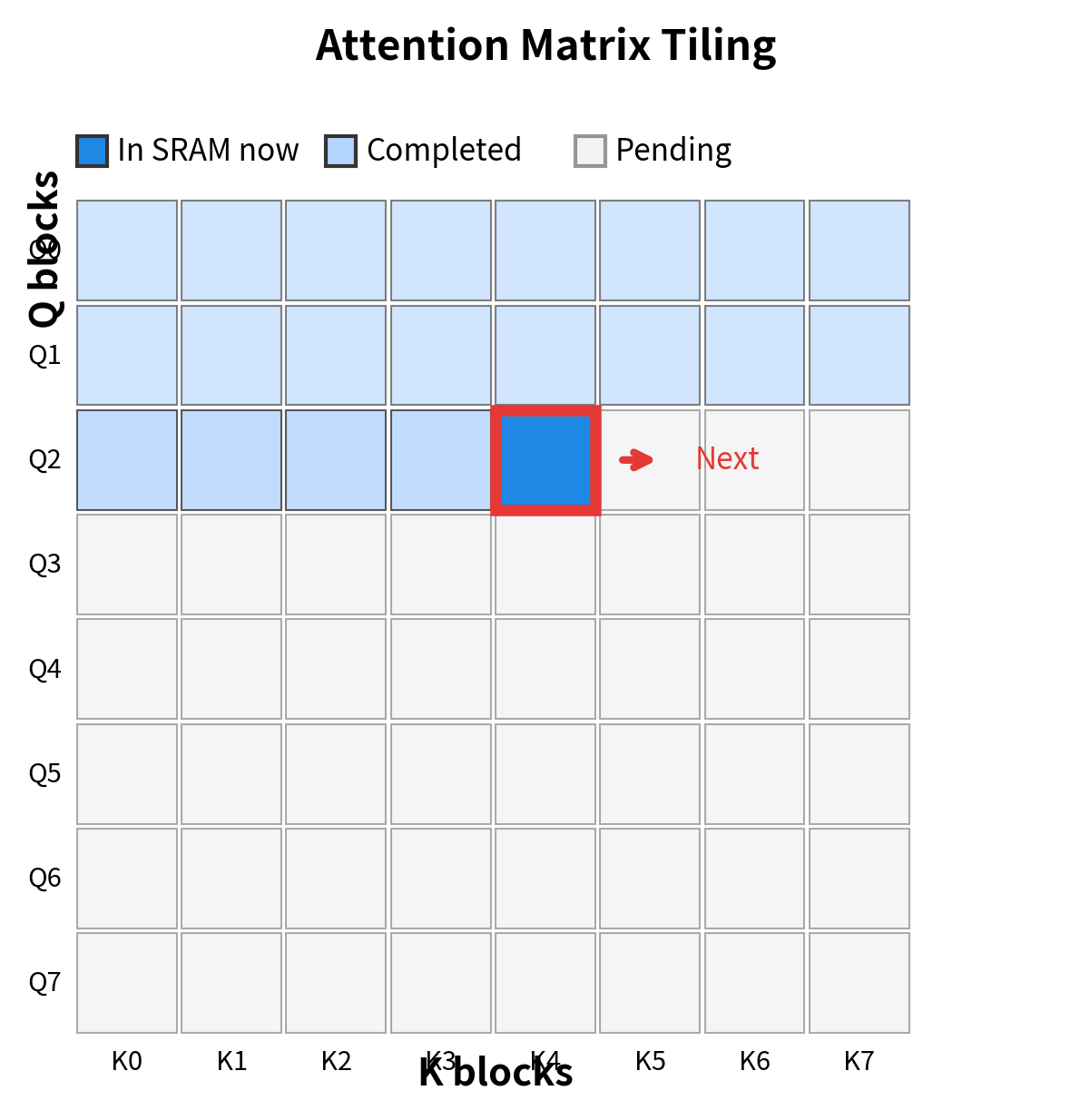

The answer lies in a technique called tiling. Rather than computing all attention scores at once and then applying softmax, FlashAttention processes attention in small chunks that fit entirely in SRAM. Each chunk computes a portion of the final output, and careful bookkeeping ensures the pieces combine to produce exactly the same result as standard attention.

The Tiling Strategy

To understand how tiling works, imagine you're computing attention for a 4096-token sequence. Standard attention would:

- Compute all million attention scores

- Store this entire matrix in memory

- Apply softmax across each row

- Multiply by the value matrix

FlashAttention takes a different approach. Instead of processing all tokens at once, it divides the computation into manageable blocks:

- Query blocks: Groups of consecutive query positions (rows of Q)

- Key-Value blocks: Groups of consecutive key-value positions (rows of K and V)

For each query block, the algorithm iterates through all key-value blocks, computing partial attention scores and accumulating results. The block sizes and are chosen specifically so that all active data fits in SRAM at once.

With 192 KB of SRAM available, we can fit query and key-value blocks of size 128, plus room for intermediate computations. The critical observation is that these block sizes are independent of sequence length: whether processing 1K or 100K tokens, each tile uses the same fixed amount of fast memory.

But there's a catch. Tiling the attention computation creates a fundamental problem that lies at the heart of FlashAttention's innovation.

The Online Softmax Trick

Here's the challenge: softmax requires global information, but we're processing local tiles.

Consider what softmax actually does. It converts a vector of raw scores into a probability distribution where all values sum to 1. Given a vector of attention scores, standard softmax computes each output element as:

where:

- : the -th attention score (the value we want to convert to a probability)

- : the exponential of , ensuring all values become positive

- : the sum of exponentials across all scores, serving as the normalizing constant

- : the total number of scores (equal to sequence length in attention)

The denominator is the problem. To compute the softmax output for any single element, we need , the sum of exponentials across all scores. But when processing tiles, we don't have all scores at once. We see positions 1-64, then 65-128, then 129-192, and so on. How can we compute a global normalization constant from local pieces?

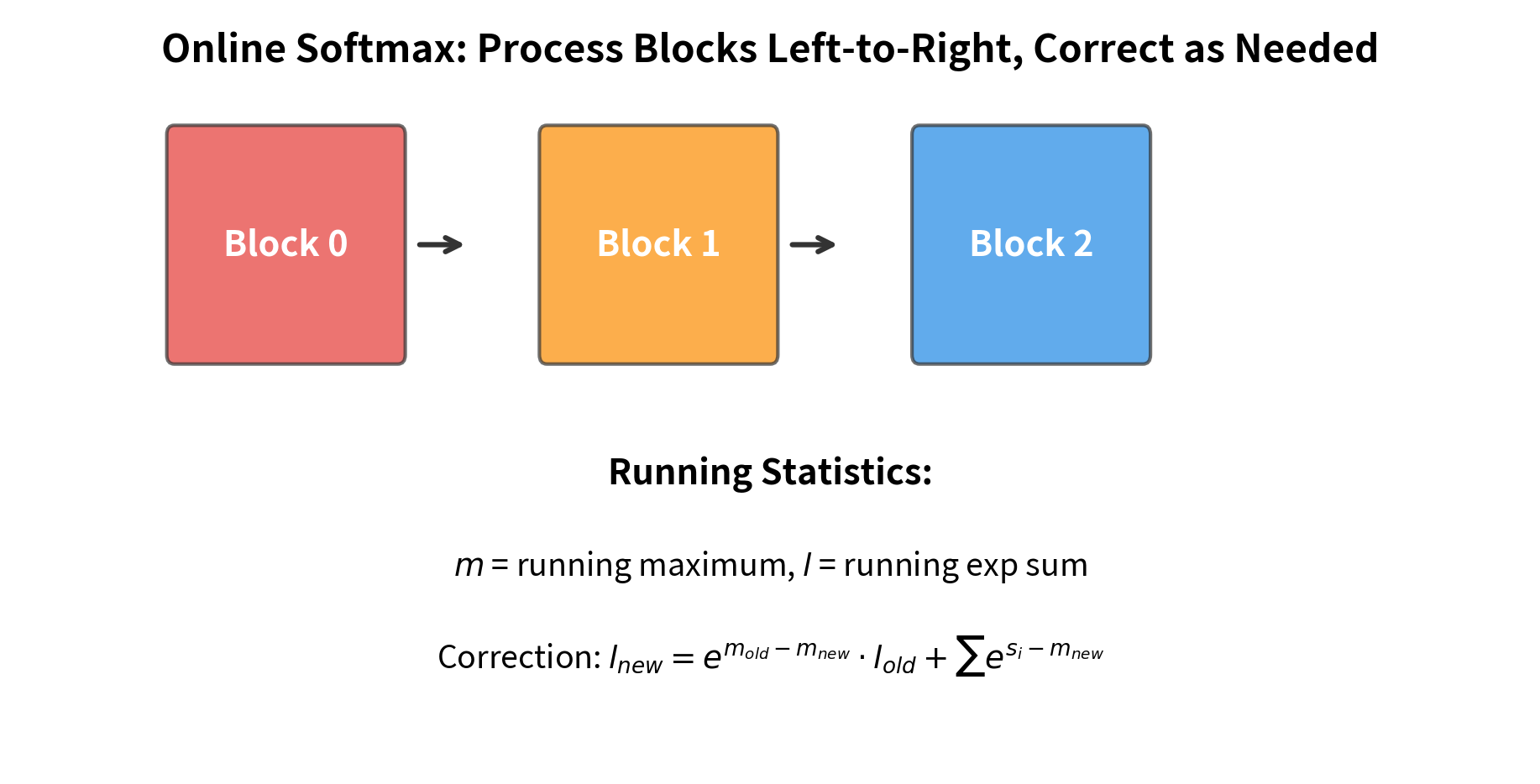

FlashAttention solves this with the online softmax algorithm, a technique that maintains running statistics and retroactively corrects previous computations as new information arrives. The key insight is that softmax can be decomposed and incrementally refined.

Building Intuition: Two Blocks

Let's start with the simplest case. Imagine we have just two blocks of scores, and . The full softmax over both is:

Now suppose we process first, before is available. At that moment, is the only score we know, so its "local softmax" is , a probability of 100%. This is wrong, of course, but we didn't have complete information.

When arrives, we can fix our mistake. The correct probability for should be . We can get this by multiplying our initial answer (1) by the correction factor:

This factor adjusts for the new, larger denominator. The pattern generalizes: as each new block arrives, we correct all previous accumulations by the ratio of old denominator to new denominator.

The Running Statistics

To make this correction efficient, FlashAttention tracks two running statistics for each query position:

- : the running maximum score seen so far

- : the running sum of exponentials (shifted by the maximum for numerical stability)

Why track the maximum? Exponentials grow quickly: is extremely large while is essentially zero. Without care, we'd overflow or underflow. By subtracting the maximum before exponentiating, we ensure all values remain in a reasonable range. This is the same trick used in numerically stable softmax implementations.

As each new tile of scores arrives, FlashAttention updates these statistics:

where:

- : the running maximum from previous blocks

- : the updated maximum after seeing the current block

- : the running sum of exponentials from previous blocks

- : the updated sum after incorporating the current block

- : the vector of attention scores in the current block

- : the correction factor that rescales previous accumulations

Why the Correction Factor Works

The correction factor is the mathematical heart of online softmax. Let's understand why it works.

When the new block contains a score larger than any we've seen before, . The difference is negative, so . This makes sense: we're discovering that the denominator should be larger than we thought, so previous contributions need to be scaled down.

When the new block has no scores exceeding our current maximum, . The correction factor becomes , leaving previous accumulations unchanged. We're simply adding to the sum without revising history.

Importantly, corrections compound correctly. If we process blocks A, then B, then C, the final answer is identical to processing them all at once. The mathematics guarantees exact equivalence, not an approximation.

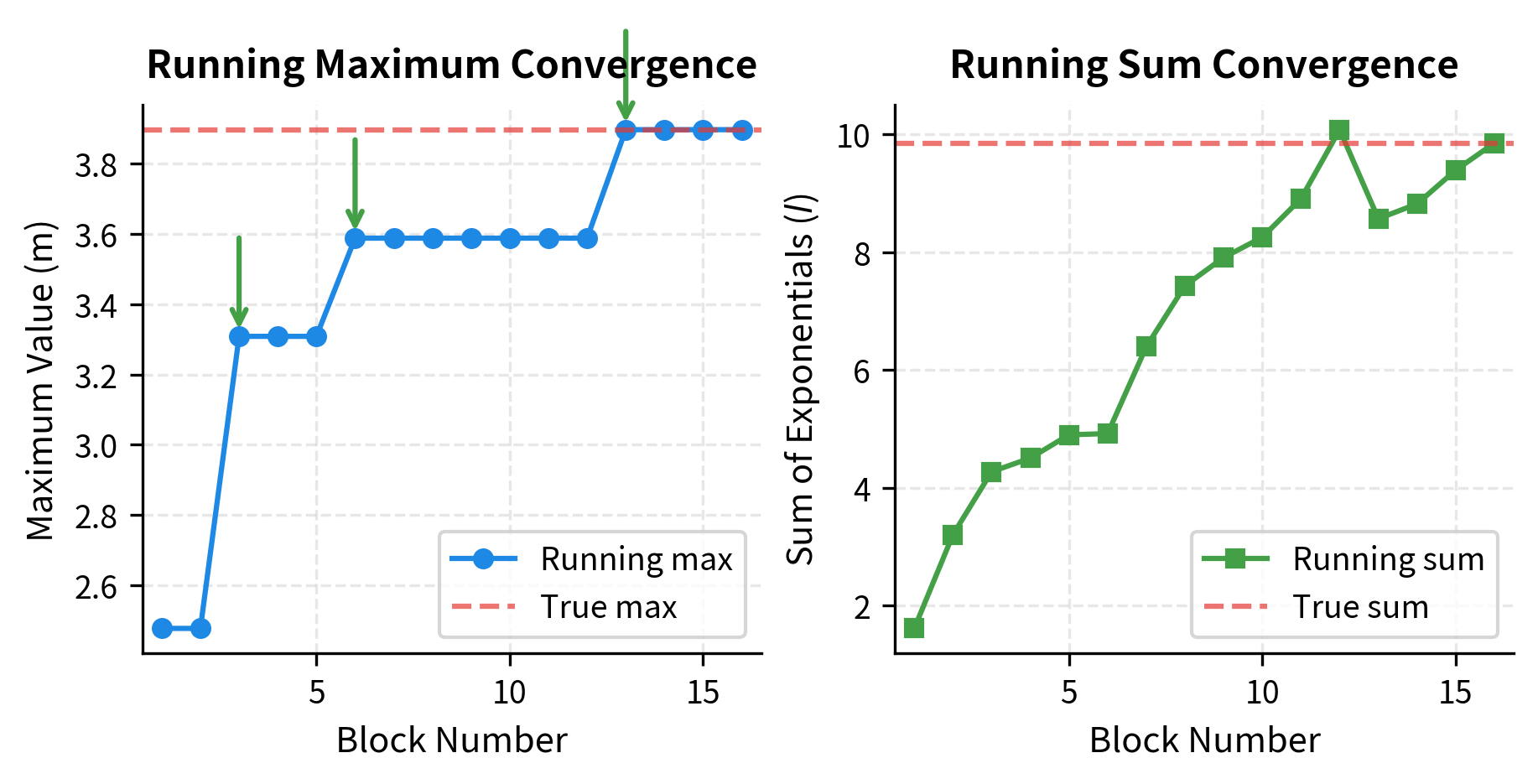

Seeing It in Action

Let's trace through the online softmax algorithm on a concrete example. We'll process three blocks of random scores and watch the running statistics evolve:

The output traces the algorithm's journey through three blocks. Notice how the running maximum updates whenever a block contains a larger value, triggering a correction factor less than 1. The running sum grows as we accumulate more exponentials. At the end, we verify that our online computation produces exactly the same sum as computing softmax over all scores at once.

The match confirms a crucial property: online softmax is not an approximation. It computes the exact same result as standard softmax, just in a different order that avoids storing all scores simultaneously.

Memory Complexity Reduction

We've now seen the two key ingredients of FlashAttention: tiling to process attention in SRAM-sized chunks, and online softmax to correctly combine partial results. Together, they enable exact attention computation without ever storing the matrix.

Let's inventory exactly what FlashAttention keeps in memory at any moment during computation:

| Component | Size | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Q block | Current query vectors being processed | |

| K block | Current key vectors for dot products | |

| V block | Current value vectors for weighted sum | |

| Output accumulator | Running weighted sum for current queries | |

| Statistics | Running and for each query | |

| Score tile | Attention scores for current block pair |

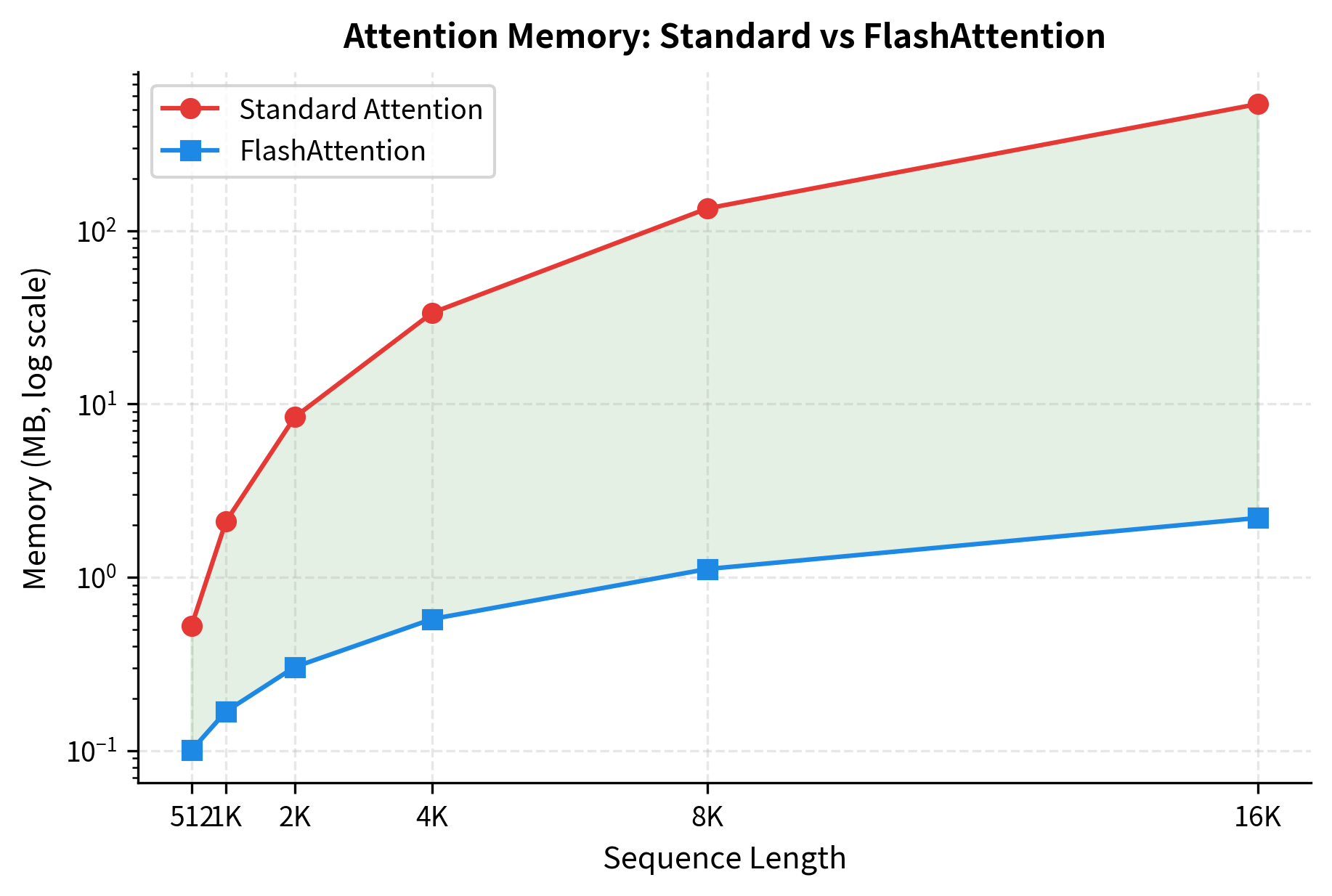

For typical settings with and , this totals about 25 KB, fitting comfortably in SRAM. The memory complexity drops from in standard attention to in FlashAttention. More precisely:

where:

- : the sequence length

- : the head dimension (typically 64-128)

- : the block size for queries (number of query rows processed together)

- : the block size for keys/values (number of key-value rows loaded at once)

- : memory for the output accumulator (one -dimensional vector per query)

- : memory for the current score tile being computed

Since , , and are constants determined by hardware constraints (not sequence length), the dominant term is , giving linear scaling with sequence length.

This is the payoff of the entire approach. Standard attention requires memory for the attention matrix, limiting sequence length to what fits in GPU memory. FlashAttention's memory means you can process arbitrarily long sequences, with memory growing only linearly. A 10x longer sequence needs only 10x more memory, not 100x.

Let's verify this with concrete numbers:

The table reveals the dramatic memory savings FlashAttention provides. At 512 tokens, standard attention requires only 0.5 MB for the attention matrix, making FlashAttention's overhead relatively larger. But as sequence length doubles, standard attention memory quadruples while FlashAttention grows linearly. By 16K tokens, standard attention consumes over 500 MB just for the attention matrix, while FlashAttention uses only about 2 MB, a reduction of over 250x. This difference determines whether a model fits in GPU memory at all.

FlashAttention-2 Improvements

FlashAttention-2, released in 2023, builds on the original algorithm with several key optimizations that improve hardware utilization from ~50-70% to ~70-90% of theoretical peak performance.

Reduced Non-Matrix-Multiply FLOPs

The original FlashAttention spent significant time on non-matrix-multiply operations: rescaling outputs, updating statistics, and coordinating between iterations. FlashAttention-2 restructures the algorithm to minimize these overheads.

The key change is delaying the rescaling of output blocks. Instead of rescaling after each K-V block, FlashAttention-2 accumulates unnormalized outputs and applies a single rescaling at the end. This requires careful bookkeeping but reduces the number of scalar operations significantly.

With 64 K-V blocks to process, FlashAttention-1 performs 4,096 rescale operations (one per query per block), while FlashAttention-2 performs only 64 (one per query at the end). This 64x reduction in rescaling operations translates directly to improved throughput, particularly when matrix multiplies are already saturating the GPU's compute units.

Better Work Partitioning

FlashAttention-2 improves how work is distributed across thread blocks and warps:

- Parallelism over batch and heads: Each thread block handles one (batch, head) pair, maximizing parallelism across the GPU

- Within-block parallelism: Different warps handle different parts of the Q block, with careful synchronization

- Sequence parallelism: For very long sequences, work can be split across multiple blocks even for a single head

Improved Memory Access

FlashAttention-2 optimizes memory access patterns in several ways:

- Swapping loops: The inner and outer loops are reordered so that the outer loop iterates over Q blocks and the inner loop over K-V blocks. This reduces the number of times Q blocks are loaded from HBM.

- Pipelining: Memory loads are overlapped with computation. While computing attention for the current K-V block, the next block is being loaded from HBM.

- Warp-level primitives: Instead of synchronizing entire thread blocks, FlashAttention-2 uses warp-level operations that are faster and more efficient.

By swapping the loop order, FlashAttention-2 reads the Q matrix 64x fewer times from HBM. This is the dominant source of the memory access reduction. Since memory bandwidth is the bottleneck, reducing redundant reads directly improves throughput.

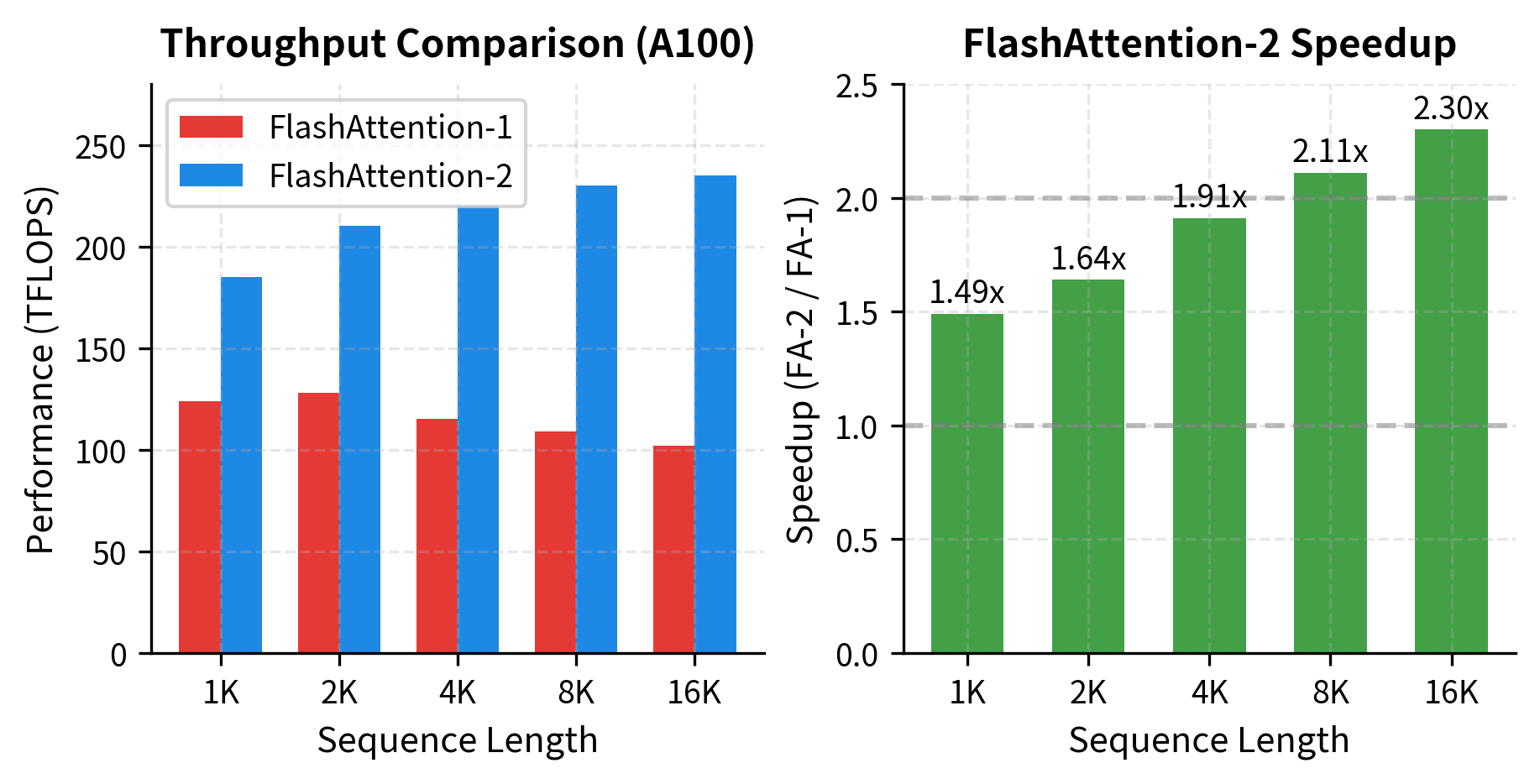

Performance Gains

These optimizations combine to give FlashAttention-2 a 2x speedup over FlashAttention on many workloads:

The benchmarks show a clear trend: FlashAttention-2's advantage grows with sequence length. At 1K tokens, the speedup is a modest 1.49x. At 16K tokens, it reaches 2.30x. This pattern occurs because longer sequences have more K-V blocks, amplifying the benefits of reduced rescaling operations and optimized memory access. FlashAttention-2 also achieves higher absolute TFLOPS, indicating better GPU utilization.

Using FlashAttention in PyTorch

The easiest way to use FlashAttention is through PyTorch's native support, added in PyTorch 2.0. The scaled_dot_product_attention function automatically uses FlashAttention when conditions permit.

Native PyTorch Integration

The output shape matches the input dimensions, confirming that attention produces one output vector per query position. When running on a CUDA-enabled GPU with fp16 tensors, PyTorch automatically selects FlashAttention as the backend, providing the memory and speed benefits without any code changes.

Controlling Attention Backend

PyTorch allows explicit control over which attention implementation to use:

Requirements and Constraints

FlashAttention has specific requirements that must be met for it to be used:

These requirements explain when PyTorch will automatically select FlashAttention. The most common reason for fallback is using float32 instead of float16/bfloat16, or using an older GPU. If you're not getting FlashAttention's benefits, check these requirements first.

Using the flash-attn Library Directly

For more control, you can use the flash-attn library directly:

Integrating with Transformers

Here's how FlashAttention integrates into a typical transformer layer:

The layer uses approximately 1 million parameters, primarily in the four linear projections (Q, K, V, and output). The head dimension of 64 is optimal for FlashAttention's performance. This implementation pattern is directly usable in production transformer models.

FlashAttention Limitations

Despite its advantages, FlashAttention has limitations that you should understand before deployment.

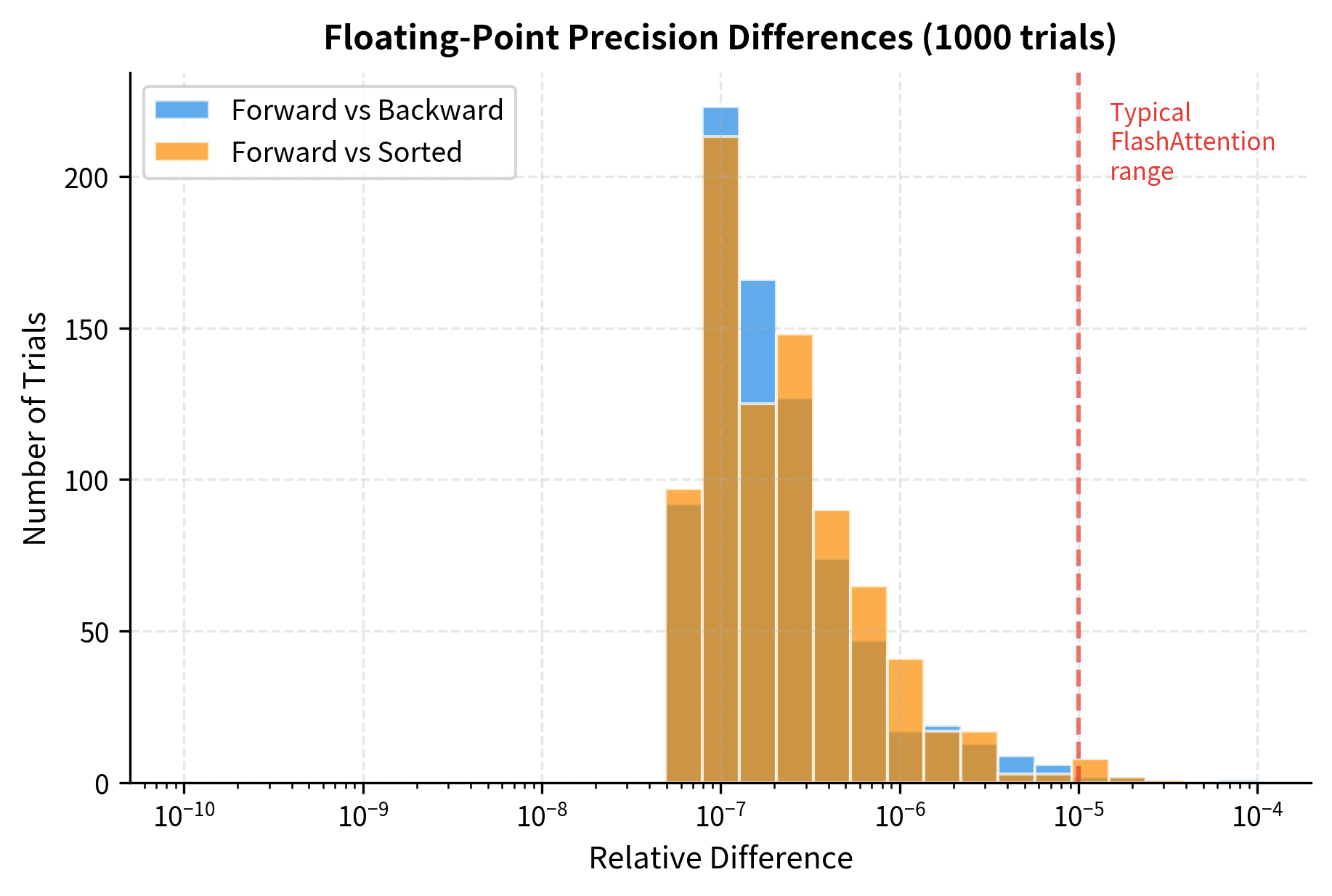

Numerical Precision Differences

FlashAttention computes attention in a different order than standard attention, which can lead to small numerical differences. While mathematically equivalent, floating-point arithmetic is not associative, so results may differ at the level of floating-point precision.

Running the same experiment 1000 times with different random values shows that these differences follow a predictable pattern:

No Arbitrary Attention Masks

FlashAttention's tiled computation assumes specific attention patterns. While causal masks and no masks are well-supported, arbitrary attention masks present challenges:

For most transformer applications, causal or no mask covers the use cases. FlashAttention-2 added sliding window support, which enables models like Mistral. For arbitrary boolean masks or complex attention biases, PyTorch falls back to the slower math kernel, losing FlashAttention's benefits.

Hardware Requirements

FlashAttention requires relatively recent NVIDIA GPUs:

Ampere and newer architectures provide full FlashAttention-2 support. Older GPUs like V100 and T4 have limited support for FlashAttention-1 only. If you're using cloud instances, A100 and H100 are the best choices for FlashAttention workloads. Consumer GPUs from the RTX 30 and 40 series also work well.

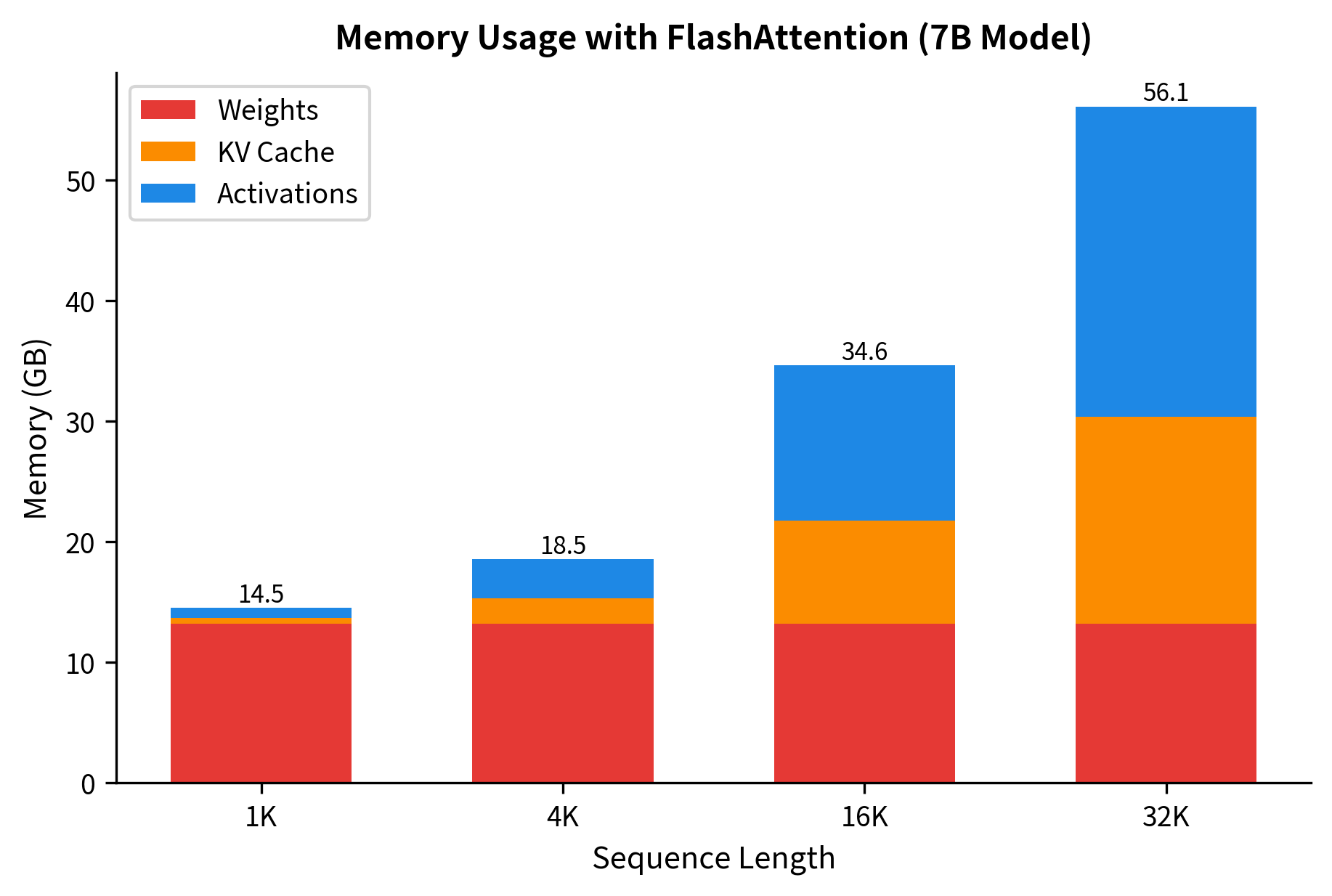

Memory Still Matters for Very Long Sequences

While FlashAttention eliminates the memory for attention matrices, other parts of the transformer still scale with sequence length:

The breakdown shows that at 4K tokens, a 7B model requires about 13 GB total. At 32K tokens, this grows to nearly 50 GB, a 4x increase. Model weights remain constant, but activations and KV cache scale linearly with sequence length. This explains why even with FlashAttention, very long sequences require substantial GPU memory or additional techniques like gradient checkpointing.

Gradient Computation

FlashAttention's recomputation strategy during the backward pass means gradients take longer to compute than they would with stored attention matrices. This is typically worthwhile because:

- The memory savings allow larger batch sizes, which often more than compensate for the recomputation cost

- Training is usually memory-bound anyway, so the extra compute fits within memory transfer time

- For very long sequences, the alternative (storing attention matrices) would be impossible

Summary

FlashAttention transforms attention computation from a memory-bound operation into one that achieves near-peak hardware utilization. The key insights and takeaways from this chapter:

-

GPU memory hierarchy: Understanding the dramatic speed difference between HBM and SRAM (10x) is essential. Standard attention repeatedly transfers data to slow HBM, while FlashAttention keeps data in fast SRAM.

-

Tiled computation: By processing attention in small blocks that fit in SRAM, FlashAttention never materializes the full attention matrix. This reduces memory complexity from to .

-

Online softmax: The online softmax algorithm maintains running statistics (maximum and sum of exponentials) that allow correct normalization without seeing all scores at once. Previous accumulations are corrected as new tiles reveal larger values.

-

FlashAttention-2 improvements: Reduced non-matrix-multiply operations, better work partitioning across threads and warps, and improved memory access patterns combine to give approximately 2x speedup over FlashAttention-1.

-

PyTorch integration: The easiest path to using FlashAttention is through

torch.nn.functional.scaled_dot_product_attention, which automatically selects FlashAttention when conditions permit (CUDA, fp16/bf16, supported head dimensions). -

Limitations: FlashAttention requires recent NVIDIA GPUs (Ampere or newer for full support), has constraints on attention mask patterns, and may produce results that differ from standard attention at floating-point precision. While it eliminates the attention matrix memory cost, activations and KV cache still scale linearly with sequence length.

FlashAttention has become the de facto standard for attention computation in modern LLMs. Models like LLaMA 2, Mistral, and most recent transformers use it by default. Understanding its implementation details helps you appreciate why it works, when it applies, and what to expect when deploying models that rely on it.

Key Parameters

When using FlashAttention, several parameters directly affect behavior and performance:

-

block_size (B_r, B_c): The tile dimensions for processing attention. Typically 64-128, determined automatically based on head dimension and SRAM availability. Larger blocks amortize memory transfer overhead but require more SRAM.

-

head_dim (d): The dimension of each attention head. FlashAttention supports specific values: 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256. Performance is best at 64 or 128.

-

causal: Whether to use causal (autoregressive) attention masking. Causal attention is optimized in FlashAttention to skip computation for masked positions entirely, not just mask them after computation.

-

dropout_p: Dropout probability during training. FlashAttention implements dropout within the kernel, avoiding the need to store dropout masks in HBM.

-

softmax_scale: Scaling factor applied before softmax, typically where is the head dimension. This prevents dot products from growing too large with higher dimensions, which would push softmax outputs toward one-hot distributions. Can be customized for specialized attention variants.

-

dtype: Data type for computation. fp16 and bf16 are fully supported and recommended. fp32 falls back to non-FlashAttention kernels in PyTorch.

-

window_size: For FlashAttention-2's sliding window support, the size of the local attention window. Set to (-1, -1) for full attention or specific values like (256, 256) for symmetric windows.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about FlashAttention and GPU memory optimization.

Comments