Master RAG system design by exploring retriever-generator interactions, timing strategies like iterative retrieval, and architectural variations like RETRO.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

RAG Architecture

The previous chapter established why retrieval-augmented generation matters: it grounds language models in external knowledge, reducing hallucinations and enabling access to information beyond the training cutoff. But understanding the motivation is only half the story. To build effective RAG systems, you need to understand how the components fit together and the design decisions that shape system behavior.

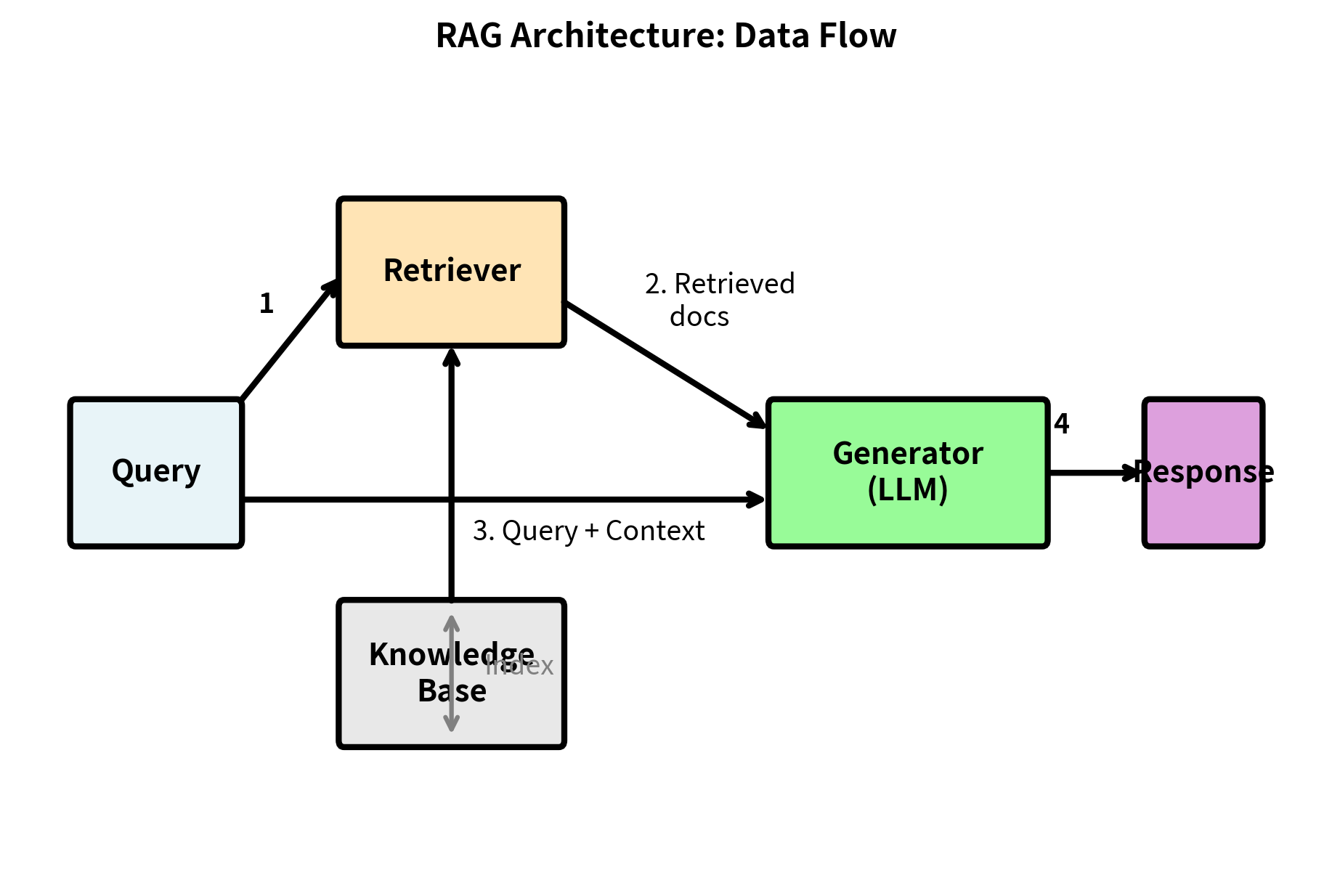

A RAG system consists of two primary components: a retriever that finds relevant documents from a knowledge base, and a generator (typically a large language model) that synthesizes an answer from those documents. These components interact through a carefully designed interface, and the timing and manner of their interaction significantly affects system performance. The retriever acts as a search engine, filtering millions of documents to identify the few most relevant ones. The generator then reads these documents and synthesizes a response that addresses your question.

This chapter examines each component in detail, explores when retrieval occurs relative to generation, and surveys the major architectural variations that have emerged since the original RAG paper. By the end, you'll understand the design space well enough to make informed decisions when building your own systems.

The Retriever Component

The retriever's job is deceptively simple: given a query, return the documents most likely to contain relevant information. However, this process is complex. The retriever must somehow measure the relevance between your question, expressed in natural language with all its ambiguity and variation, and documents that may discuss the same concepts using entirely different vocabulary. In practice, achieving this involves three sub-systems working together: document encoding, indexing, and query-time retrieval.

Document Encoding

Before retrieval can happen, documents must be transformed into a searchable representation. Raw text, while meaningful to humans, cannot be efficiently compared or searched by algorithms. The encoding process bridges this gap, converting human-readable text into mathematical objects that computers can manipulate. This process typically involves two stages that work together to prepare documents for rapid, accurate retrieval.

First, documents are split into smaller chunks. A 50-page technical report cannot be fed to a language model in its entirety, so we divide it into passages of a few hundred tokens each. The chunking strategy significantly affects retrieval quality: too small and you lose context, too large and you dilute relevant information with noise. Consider a chunk that contains only half a sentence: the retriever might match it to a query based on keyword overlap, but the generator would receive incomplete, potentially misleading information. Conversely, a chunk spanning multiple pages might contain one relevant paragraph buried among irrelevant content, making it harder for the generator to identify what matters. We'll explore chunking strategies in depth in a later chapter, examining techniques like overlapping windows, semantic boundary detection, and hierarchical chunking.

Second, each chunk is converted into a numerical representation suitable for similarity search. This transformation is the heart of the retrieval process, determining how the system measures whether one piece of text relates to another. Two broad approaches dominate the field, each with distinct characteristics:

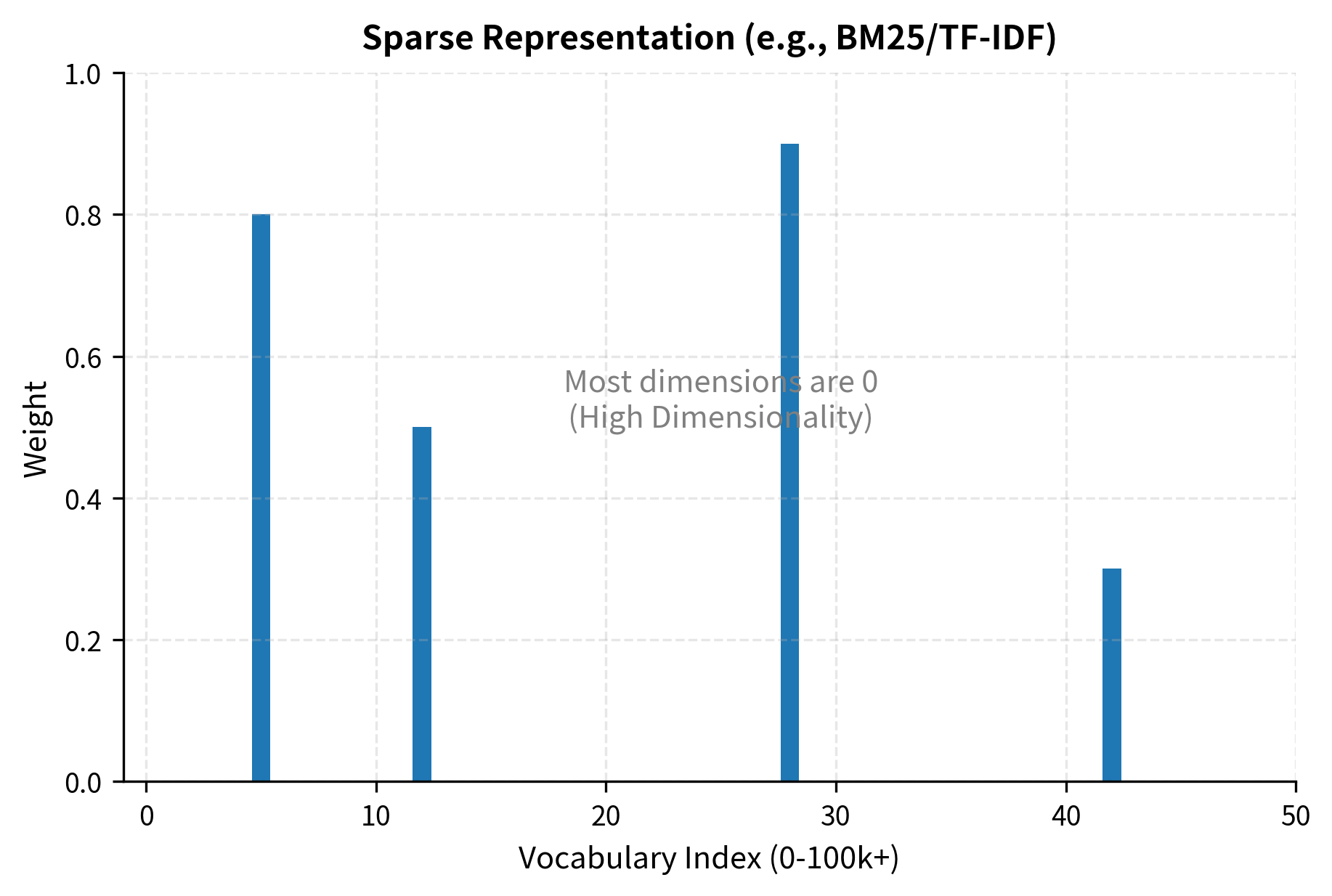

Sparse representations like TF-IDF and BM25 represent documents as high-dimensional vectors where each dimension corresponds to a vocabulary term. As we covered in Part II, BM25 scores documents based on term frequency, document length normalization, and inverse document frequency. The intuition behind sparse representations is straightforward: documents are characterized by the words they contain. A document about neural networks will have non-zero values for terms like "neuron," "layer," and "activation," while a document about cooking will have non-zero values for entirely different terms. These representations are sparse because most terms don't appear in any given document, leaving most dimensions at zero. A vocabulary might contain 100,000 terms, but any single document uses only a few hundred, resulting in vectors that are more than 99% zeros.

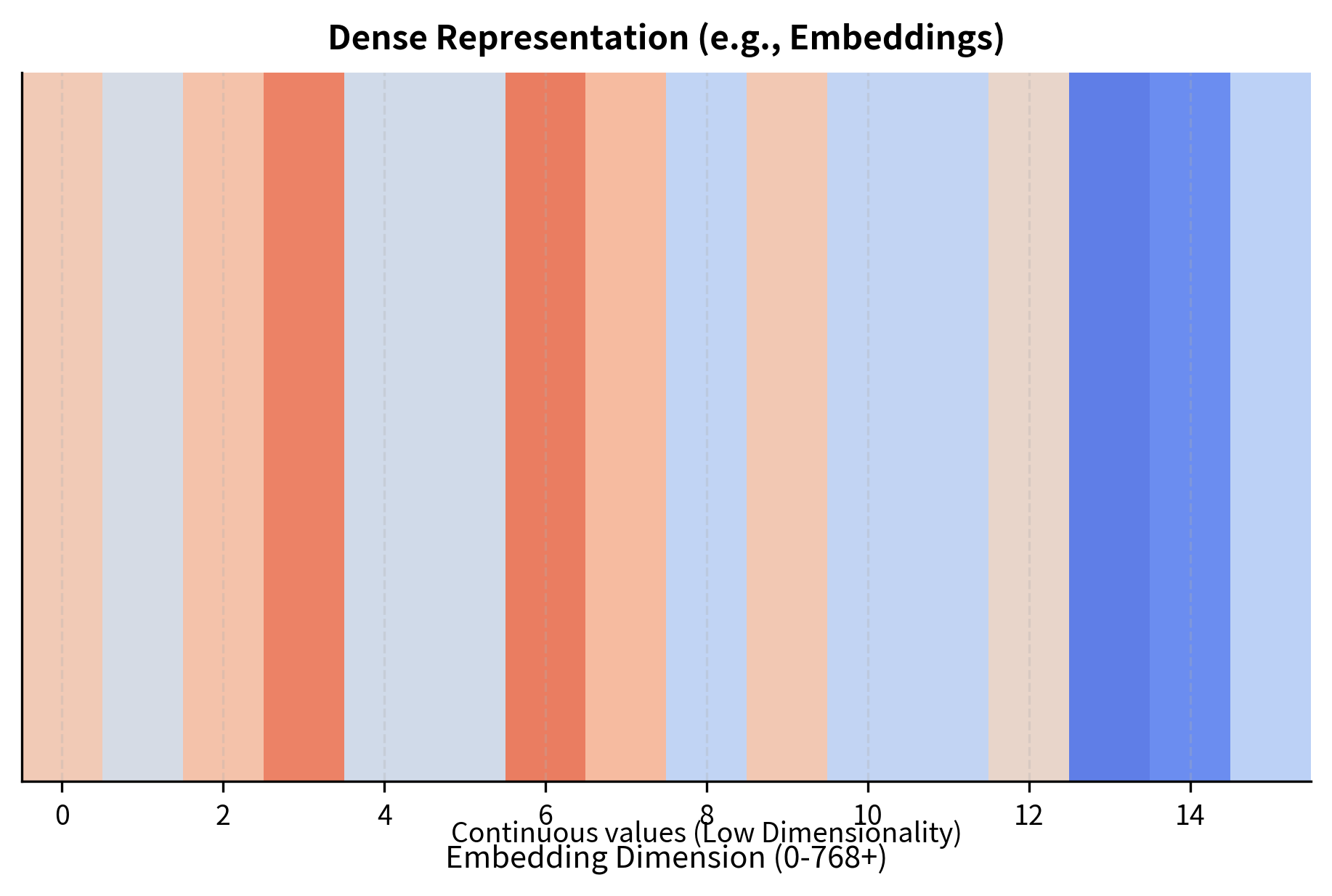

Dense representations use neural networks to encode chunks into continuous vectors, typically with 384 to 4096 dimensions. Unlike sparse vectors where dimensions correspond to specific words, dense embedding dimensions capture abstract semantic features that emerge during training. These features don't have human-interpretable names; instead, they represent learned patterns that help distinguish relevant from irrelevant content. Two documents discussing the same concept with different vocabulary will have similar dense embeddings even if their sparse representations share few non-zero dimensions. For example, a query about "car maintenance" would find documents discussing "vehicle repair" or "automobile servicing" because the neural network has learned that these phrases occupy similar regions of the embedding space.

The choice between sparse and dense retrieval involves trade-offs we'll examine in the next chapter. Sparse methods are fast, interpretable, and require no training data, making them excellent baselines. Dense methods capture semantic similarity that keyword matching misses but require substantial training data and computational resources. For now, recognize that both approaches solve the same fundamental problem: converting text into vectors that can be compared for similarity.

The Index

Encoded documents are stored in an index optimized for fast similarity search. Without an index, finding the most similar documents to a query would require computing similarity with every document in the collection. For a knowledge base with millions of documents, this brute-force approach would take seconds or minutes per query, far too slow for interactive applications. The index structure depends on the retrieval approach, with each type of representation requiring specialized data structures.

For sparse retrieval, inverted indexes map each vocabulary term to the list of documents containing that term. The name "inverted" reflects that instead of mapping documents to their terms (the natural way we think about a document), we map terms to their documents. When a query arrives, the system looks up query terms, retrieves candidate documents containing those terms, and scores them using BM25 or similar formulas. This is the same technology powering web search engines, refined over decades to handle billions of documents with sub-second query times. The inverted index dramatically reduces computation because most queries contain only a handful of terms, and each term appears in only a fraction of documents.

For dense retrieval, vector indexes organize embeddings to enable efficient nearest-neighbor search. Comparing a query embedding against millions of document embeddings naïvely requires millions of distance calculations, each involving hundreds or thousands of floating-point operations. Specialized data structures like Hierarchical Navigable Small World graphs (HNSW) and Inverted File indexes (IVF) reduce this to thousands or hundreds of comparisons through clever approximations. HNSW builds a multi-layer graph where each node connects to its nearest neighbors, allowing search to quickly navigate toward the most relevant region of the embedding space. IVF partitions the embedding space into clusters and searches only the clusters closest to the query vector. These approximations trade a small amount of accuracy for dramatic speed improvements. We'll cover these algorithms in detail in upcoming chapters on vector similarity search.

Retrieval at Query Time

When your query arrives, the retriever executes a specific sequence of operations. First, it encodes the query using the same method applied to documents. For sparse retrieval, this means computing BM25 term weights for the query terms. For dense retrieval, this means passing the query through the same neural encoder that embedded the documents. This symmetry is essential: queries and documents must inhabit the same representation space for similarity comparisons to be meaningful.

Second, the retriever searches the index for the k most similar documents. For sparse retrieval, this involves looking up query terms in the inverted index and combining the results. For dense retrieval, this involves navigating the vector index to find the nearest neighbors of the query embedding. In both cases, the index structure transforms what would be an exhaustive search into a targeted lookup.

Third, the retriever returns those documents along with their similarity scores. These scores serve multiple purposes: they determine the ranking order, they can filter out low-quality matches, and they can inform the generator about the relative confidence of different sources.

The parameter (typically 3-10 documents) balances coverage against noise. Too few documents risk missing relevant information; too many dilute the generator's context with marginally relevant passages. The optimal value of depends on your use case: simple factual questions might need only one or two relevant passages, while complex analytical queries might benefit from synthesizing information across many sources.

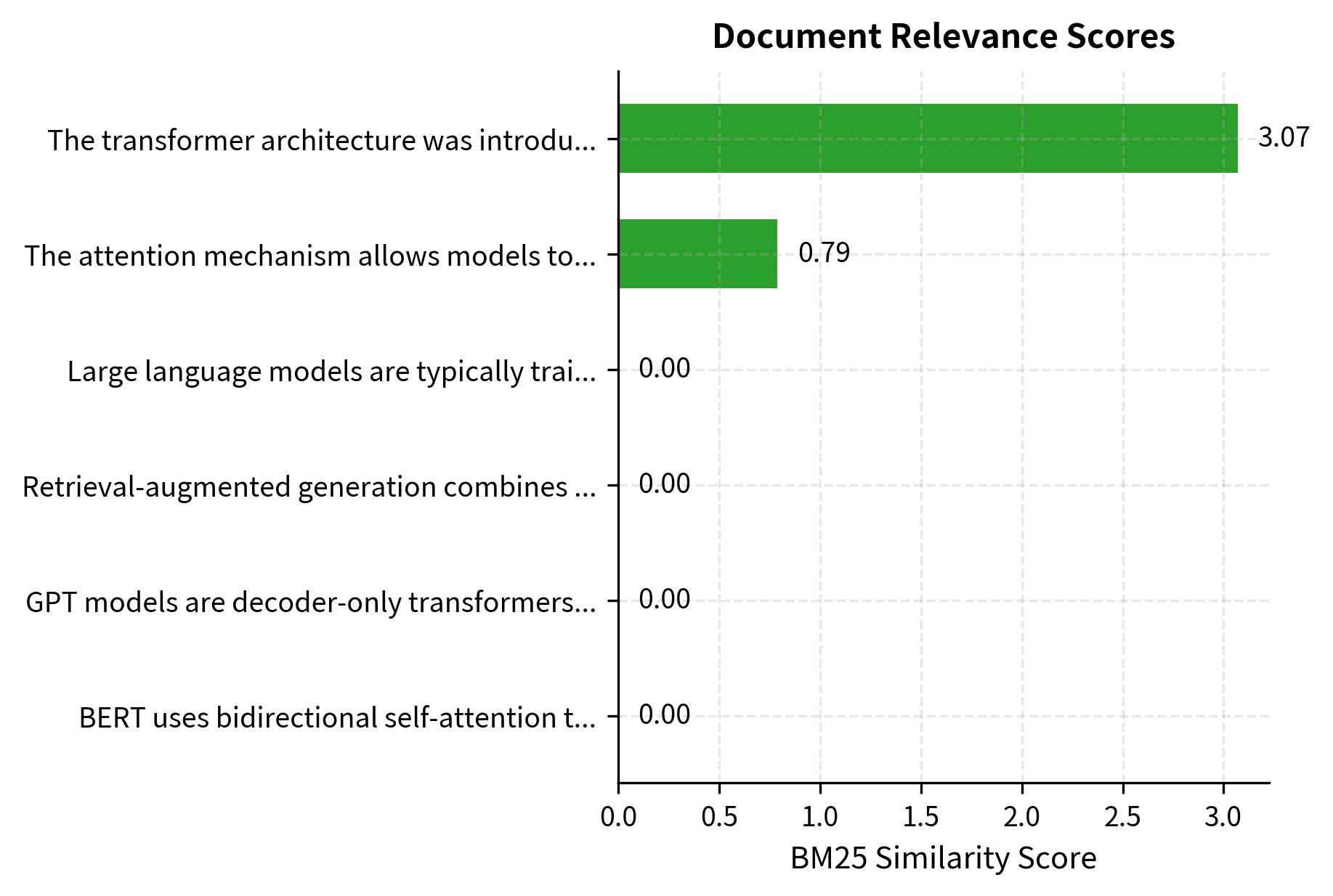

BM25 retrieves documents sharing query terms like "transformer" and "architecture." The scores reflect term overlap, frequency, and document length normalization as defined by the BM25 formula we covered in Part II. Notice that the highest-scoring document explicitly mentions both "transformer" and "architecture," while lower-ranked documents may match only one of these key terms or match through related vocabulary.

The Generator Component

The generator takes the retrieved documents and the original query, then produces a natural language response. In modern RAG systems, this is almost always a large language model, either an API-based model like GPT-4 or an open-weight model like LLaMA. The generator's role extends beyond simple information extraction: it must understand the query's intent, identify relevant portions of the retrieved documents, resolve any conflicts between sources, and synthesize a coherent, well-structured response.

Context Integration

The most straightforward approach to context integration is prompt concatenation: retrieved documents are inserted into the prompt before the query, giving the model access to relevant information through its standard attention mechanism. This approach requires no architectural modifications to the language model; we simply provide additional context that the model can reference during generation.

A typical RAG prompt structure looks like:

Context:

[Document 1]

[Document 2]

[Document 3]

Question: [User query]

Answer based on the context above:

The generator reads this concatenated input and generates a response, attending to both the query and the retrieved documents. This leverages the in-context learning capabilities we discussed in Part XVIII: the model learns to extract and synthesize information from the provided context without any weight updates. The model has been trained on countless examples of reading passages and answering questions, so it naturally applies these learned behaviors to the RAG setting. The key insight is that prompt concatenation transforms the generation task into something the model already knows how to do well.

Attention Over Retrieved Context

From the model's perspective, retrieved documents are simply additional tokens in the input sequence. There is no special mechanism distinguishing context from query; both are processed uniformly by the same transformer layers. The self-attention mechanism, which we covered extensively in Part X, allows every generated token to attend to every token in the context. This means the model can:

- Identify which parts of which documents are relevant to the query by computing high attention weights for informative passages and low weights for irrelevant ones

- Synthesize information across multiple documents, combining facts from different sources into a unified answer

- Resolve contradictions or prioritize more specific information, implicitly judging which source is more authoritative or relevant

The attention patterns often reveal which documents influenced the response. Tokens in the generated answer attend strongly to the specific passages they're drawing from, creating an implicit citation mechanism. Researchers have exploited this property to build attribution systems that highlight which retrieved passages contributed to each part of the generated response. While not a formal guarantee of faithfulness, these attention patterns provide valuable interpretability.

Prompt Engineering for RAG

The exact prompt template significantly affects generation quality. Small changes in wording can substantially alter the model's behavior, determining whether it faithfully uses the context, hallucinations confidently, or appropriately expresses uncertainty. Key considerations include:

- Instruction clarity: Explicitly telling the model to base its answer on the provided context reduces hallucination. Phrases like "Answer based only on the documents above" or "If the information isn't in the context, say you don't know" provide clear behavioral guidance.

- Document ordering: Models sometimes exhibit position bias, attending more to documents at the beginning or end of the context. Important documents might be placed in these privileged positions, or the order might be randomized to reduce systematic bias.

- Attribution requests: Asking the model to cite which documents it used can improve traceability. Requests like "Reference the document numbers in your answer" encourage the model to explicitly connect claims to sources.

- Uncertainty expression: Instructing the model to say "I don't know" when context is insufficient prevents confident hallucinations. Without this instruction, models often generate plausible-sounding answers even when they lack the information to do so correctly.

This prompt template makes the task explicit: use the documents, cite uncertainty when appropriate. The numbered document format enables the model to reference specific sources in its response, improving traceability and helping you verify the generated information.

Retrieval Timing

A crucial architectural decision is when retrieval occurs relative to generation. This timing choice affects latency, complexity, and the types of queries the system can handle effectively. Different timing strategies suit different use cases.

Single-Shot Retrieval

The simplest approach retrieves documents once, before generation begins. The query goes to the retriever, documents come back, and generation proceeds with that fixed context. In this approach, the query flows first to the retriever, which searches the index and returns relevant documents. These documents, along with the original query, are then combined into a prompt and sent to the generator, which produces the final response.

Single-shot retrieval works well when:

- The query clearly specifies what information is needed

- Retrieved documents are likely to contain complete answers

- Low latency is critical (one retrieval round-trip)

Most production RAG systems use single-shot retrieval because it's fast, simple, and effective for straightforward queries. The architecture is easy to reason about, debug, and optimize.

Iterative Retrieval

Complex queries sometimes require multiple retrieval steps. The model might need to first retrieve background information, then use that to formulate more specific sub-queries. In iterative retrieval, the process begins with an initial retrieval based on your query, followed by partial generation that may reveal the need for additional information. The system then performs additional retrieval to fill in gaps, followed by final generation that synthesizes all retrieved content into a complete response.

Consider the query: "Compare the economic impact of the 2008 and 2020 recessions." A single retrieval might not return sufficiently comparable information about both events. The query contains two distinct information needs, and the knowledge base might organize information about each recession separately. Iterative retrieval allows the system to:

- Retrieve documents about the 2008 recession

- Retrieve documents about the 2020 recession

- Synthesize a comparison using both sets of documents

The trade-off is latency and complexity. Each retrieval adds round-trip time and requires logic to determine when additional retrieval is needed. The system must decide how to decompose complex queries and when it has gathered sufficient information to generate a final answer.

Token-Level Retrieval

At the opposite extreme from single-shot, some architectures retrieve new documents for each token generated. The RETRO (Retrieval-Enhanced Transformer) architecture interleaves retrieval throughout generation, attending to freshly retrieved passages at regular intervals. This approach ensures that the retrieved context remains relevant even as generation shifts to new topics or sub-questions.

This approach can maintain relevance as generation shifts topics, but the computational overhead is substantial. Each retrieval operation adds latency, and performing thousands of retrievals (one per token) quickly becomes impractical. Token-level retrieval is primarily a research technique rather than a production pattern, though its insights have influenced more practical architectures.

Query-Time vs. Index-Time Retrieval

An orthogonal timing dimension is when document processing occurs. This choice affects the trade-off between preparation time (when documents are added) and response time (when queries arrive).

Index-time processing pre-computes everything possible: chunking, embedding, and indexing happen once when documents are added to the knowledge base. Query-time only computes query encoding and index lookup. This approach minimizes latency for you but requires re-processing documents whenever the chunking strategy or embedding model changes.

Query-time processing delays some computation until a query arrives. For example, the system might store raw documents and compute embeddings using a query-dependent prompt. This enables more sophisticated relevance scoring at the cost of latency. Some hybrid approaches pre-compute base embeddings but compute additional query-specific features at query time.

Most systems favor aggressive index-time processing to minimize query latency, accepting the overhead of re-indexing when configurations change.

Architecture Variations

Since the original RAG paper, researchers and practitioners have developed numerous architectural variations. Understanding these helps you choose or design the right architecture for your use case. Each variation makes different trade-offs between simplicity, performance, and capability.

Retrieve-then-Read (Sequential RAG)

The standard architecture we've been describing is sometimes called "retrieve-then-read": retrieve first, then read (generate). Documents pass through a clean interface: the retriever's output becomes the generator's input. This separation creates a clear contract between components: the retriever promises to return relevant documents, and the generator promises to synthesize them into an answer.

This clean separation enables independent optimization of each component. You can upgrade the retriever without touching generation logic, or swap in a different LLM without modifying retrieval. This modularity also simplifies debugging: if answers are wrong, you can examine retrieved documents to determine whether the problem is in retrieval (wrong documents) or generation (right documents, wrong answer).

Fusion-in-Decoder

The Fusion-in-Decoder (FiD) architecture processes each retrieved document independently through the encoder, then fuses their representations in the decoder. This approach addresses a scalability challenge with the standard concatenation approach.

Instead of concatenating all documents into a single input, which creates one long sequence that grows linearly with the number of documents, FiD keeps encoding costs constant per document by encoding each document-query pair separately. Each encoding produces a fixed-size representation, and these representations are concatenated for the decoder. The decoder then attends over all document representations simultaneously when generating the answer.

This approach scales better with the number of retrieved documents. Standard concatenation creates a sequence of length where is average document length and is the number of documents, and attention cost grows quadratically with sequence length. FiD keeps each encoder pass at length , with only the decoder needing to handle the combined representations. This allows FiD to process many more documents than would be practical with simple concatenation.

Retrieval-Augmented Language Models (REALM/RAG)

The original RAG paper from Facebook AI and the REALM paper from Google both proposed end-to-end trainable retrieval. Rather than using a frozen retriever, these architectures backpropagate gradients through the retrieval step. This means the retriever can learn not just what documents are similar to the query, but what documents are actually useful for generating correct answers.

The key insight is treating retrieval as a latent variable. In this formulation, we don't commit to using a single retrieved document. Instead, we consider multiple retrieved documents and weight their contributions by how relevant the retriever believes them to be. Given query and a set of retrieved documents , the probability of generating answer is computed by marginalizing over the documents:

where:

- : the generated answer

- : the input query

- : the -th retrieved document

- : the number of retrieved documents

- : the probability of the generator producing answer given query and document (the likelihood of the answer based on this specific document)

- : the probability of the retriever selecting document given query (the relevance weight for this document)

This formulation computes a weighted average of the generator's predictions, mixing them according to the retriever's confidence. Each document contributes to the final answer probability in proportion to how relevant the retriever believes it to be. If the retriever assigns high probability to a document that helps generate the correct answer, and low probability to documents that would lead to wrong answers, the system performs well.

The core advantage of this approach is its differentiability. Because both terms in the product are differentiable, gradients flow from the generation loss back to the retriever, teaching it what documents are actually useful for answering questions. If the generator consistently produces wrong answers when using certain documents, the retriever learns to down-weight those documents for similar queries.

Training end-to-end is expensive because updating document embeddings requires re-indexing, which can take hours for large knowledge bases. However, the resulting retrievers are specifically optimized for the generation task, often outperforming generic retrievers by substantial margins.

RETRO: Chunked Cross-Attention

The RETRO (Retrieval-Enhanced Transformer) architecture from DeepMind takes a different approach, building retrieval into the transformer architecture itself. Rather than treating retrieval as a preprocessing step, RETRO makes retrieval an integral part of the model's forward pass.

RETRO divides the input into chunks and retrieves neighbors for each chunk. These neighbors are documents from the knowledge base that are similar to the current chunk being processed. Retrieved neighbors are processed by a separate encoder, and their representations are integrated through chunked cross-attention layers interleaved with standard self-attention. This means the model alternates between attending to its own representations (self-attention) and attending to retrieved content (cross-attention).

This tight integration allows RETRO to scale retrieval to trillions of tokens while keeping the main model relatively small. The model can effectively "look up" information during generation rather than storing all knowledge in its parameters. A 7B parameter RETRO model can match the performance of a 25B model without retrieval by leveraging a massive retrieval database. This represents a fundamental shift in how we think about model capacity: some knowledge lives in parameters, while other knowledge lives in an external database accessed through retrieval.

Self-RAG: Retrieval as a Learned Decision

Most RAG systems retrieve for every query, but retrieval isn't always necessary. Simple queries like "What is 2+2?" don't benefit from retrieval, and retrieving irrelevant documents can actually hurt performance by confusing the generator. Self-RAG trains models to decide when to retrieve, what to retrieve, and how to use retrieved content.

The model generates special tokens indicating its reasoning about retrieval:

- [Retrieve]: Whether retrieval is needed for this query

- [IsREL]: Whether a retrieved passage is relevant

- [IsSUP]: Whether a passage supports the generated claim

- [IsUSE]: Whether to use a passage in generation

These reflection tokens enable the model to critique its own retrieval usage, filtering irrelevant documents and identifying when it should rely on parametric knowledge instead. This introspective capability makes Self-RAG more adaptive than systems that blindly retrieve for every query. The model learns when retrieval helps and when it hurts, applying retrieval selectively to maximize answer quality.

Building a Complete RAG Pipeline

Let's assemble the components into a working RAG system. We'll use a sparse retriever for simplicity; the next chapter covers dense retrieval in depth. This implementation demonstrates the core patterns you'll use in production systems, even though real systems would connect to actual language model APIs.

The pipeline retrieves the three most relevant documents (those mentioning "transformers," "attention," and related concepts) and then constructs a prompt instructing the model to answer based on this context. Notice how the BM25 scores reflect the degree of term overlap between the query and each document, with the highest-scoring document containing the exact phrase "key innovation of transformers."

Handling Edge Cases

Production RAG systems need to handle several edge cases gracefully. Not every query will have good matches in the knowledge base, and the system should behave appropriately in these situations rather than hallucinating or returning nonsensical results.

When retrieval scores are low, the system might:

- Fall back to the model's parametric knowledge

- Return "I don't know" rather than hallucinating

- Trigger a different retrieval strategy (expand query, search different index)

The appropriate action depends on your use case. A customer support bot might need to always provide some answer, while a medical information system might need to be conservative and admit uncertainty.

Key Parameters

The key parameters for the RAG pipeline are:

- k: Number of documents to retrieve. Balances context coverage against noise. Typical values range from 3 to 10, with lower values for focused queries and higher values for broad research questions.

- score_threshold: Minimum similarity score required to consider a document relevant. This threshold depends on the retrieval method and should be tuned on representative queries.

- max_tokens: Maximum number of tokens to generate in the response. Longer limits allow more comprehensive answers but increase latency and cost.

Data Flow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates how data flows through a RAG system:

The numbers indicate the sequence: (1) the query goes to the retriever, (2) relevant documents return from the knowledge base, (3) the query and retrieved context combine into a prompt, and (4) the generator produces the final response.

Comparing Architecture Variants

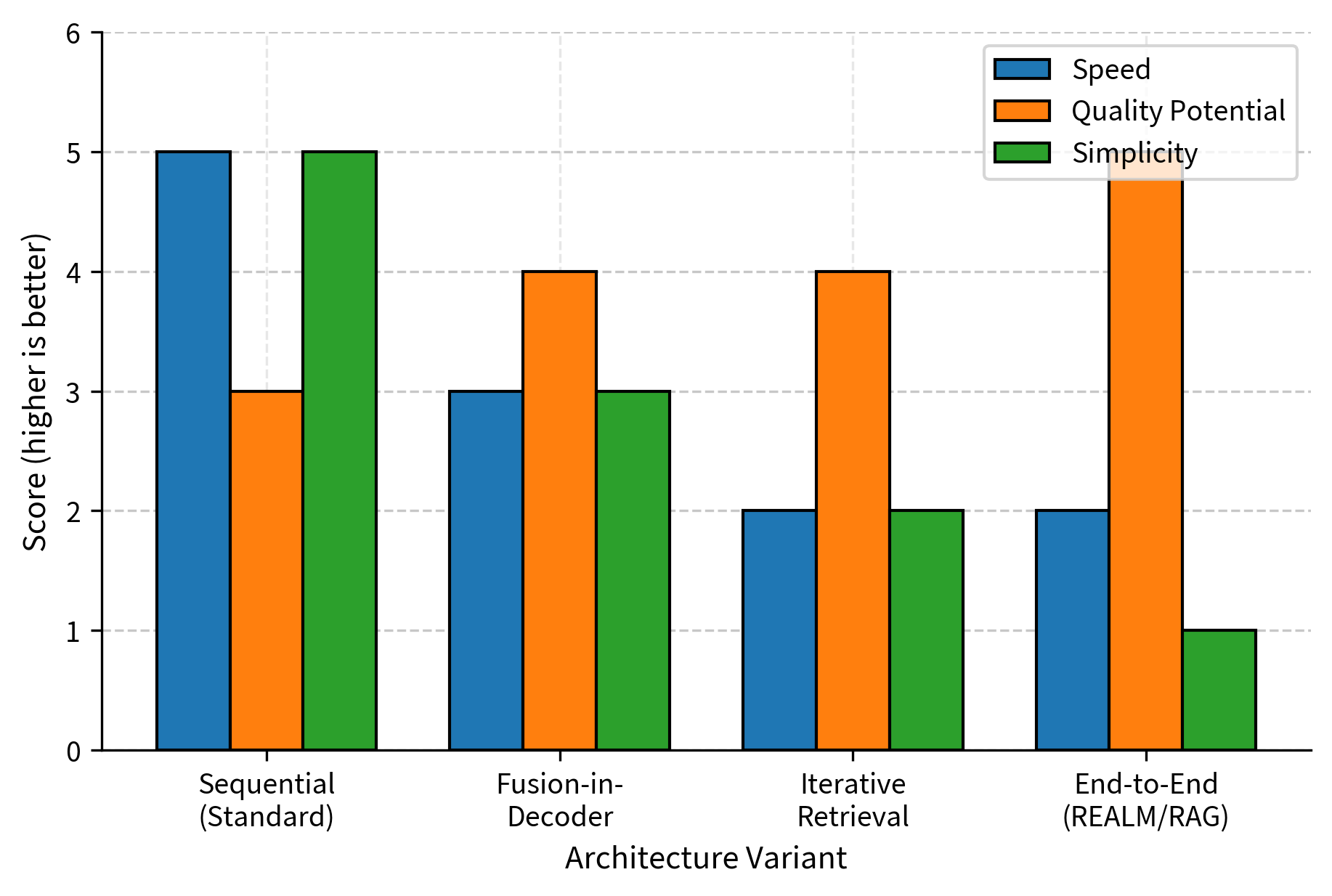

Different RAG architectures trade off latency, quality, and complexity:

Sequential RAG dominates in production because it's fast and simple while delivering good quality. Fusion-in-Decoder trades some speed for better multi-document reasoning. Iterative retrieval handles complex queries but adds latency. End-to-end training maximizes quality but requires significant infrastructure investment.

Limitations and Considerations

RAG architecture decisions involve inherent trade-offs that you should understand before building systems. These limitations don't make RAG ineffective; rather, they define the boundaries within which RAG excels and help you set appropriate expectations.

Context window constraints remain a fundamental limitation. Even with modern models supporting 100K+ token contexts, there's a practical limit to how many documents you can retrieve. As we discussed in Part XIV on efficient attention and Part XV on context extension, attention costs grow with sequence length, and models can struggle to effectively use information buried deep in long contexts. Research has shown that models tend to focus on information at the beginning and end of the context, with middle sections receiving less attention. This "lost in the middle" phenomenon means retrieval quality matters enormously: retrieving the right 3 documents beats retrieving 30 marginally relevant ones.

The retriever-generator mismatch problem arises because these components are typically trained separately. A retriever optimized for traditional information retrieval metrics may not retrieve what's actually most useful for generation. A passage that scores highest on BM25 might lack the specific details the generator needs, while a lower-ranked passage contains exactly the right information. The retriever knows about word overlap and semantic similarity, but it doesn't know what the generator needs to answer the specific question. End-to-end training addresses this but requires substantial infrastructure. The hybrid search and reranking approaches we'll cover in later chapters offer pragmatic middle grounds that improve alignment without the full cost of end-to-end training.

Latency accumulates across the pipeline. Retrieval adds round-trip time to the knowledge base (potentially remote), and longer contexts increase generation time due to the attention mechanism processing more tokens. For real-time applications, this motivates careful optimization: caching frequent queries, using smaller models, or pre-computing responses for common question patterns. Each additional retrieved document adds both retrieval time (searching for more results) and generation time (more tokens for the model to process), creating compound latency effects.

Attribution and faithfulness remain active research areas. When a RAG system generates an answer, how do you verify it actually came from the retrieved documents rather than hallucinated parametric knowledge? The model might confidently state a fact that appears nowhere in the retrieved context, drawing instead from knowledge encoded in its weights during pretraining. Current approaches include asking models to cite sources, comparing responses with and without context, or using specialized fact-verification models. None are fully reliable, making RAG a tool that reduces rather than eliminates hallucination risk. You should understand that retrieved documents provide evidence for the answer, but the system may still make errors in how it interprets or synthesizes that evidence.

Summary

This chapter examined the architecture of retrieval-augmented generation systems, revealing how seemingly simple "retrieve then generate" conceals important design decisions.

The retriever component transforms documents into searchable representations (sparse or dense), stores them in specialized indexes, and returns the most relevant passages at query time. The choice of retrieval method, such as BM25, dense embeddings, or hybrid approaches, significantly affects what information reaches the generator.

The generator component synthesizes answers from retrieved context using in-context learning. Prompt design matters: clear instructions, appropriate document formatting, and explicit uncertainty handling all improve output quality.

Retrieval timing ranges from single-shot (fast, simple) to iterative (handles complex queries) to token-level (maximum relevance, maximum overhead). Most production systems use single-shot retrieval with potential fallback to iteration for hard queries.

Architecture variations like Fusion-in-Decoder, RETRO, and Self-RAG demonstrate that the basic sequential pattern is just one point in a large design space. Each variant trades off latency, quality, and complexity differently.

The next chapter dives deep into dense retrieval: how neural networks learn to embed queries and documents into the same vector space, enabling semantic matching that goes far beyond keyword overlap. This is the technology that makes modern RAG systems substantially more capable than their sparse retrieval predecessors.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about RAG architecture.

Comments