Discover why LLMs need Retrieval-Augmented Generation. Learn how RAG bridges knowledge gaps, reduces hallucinations, and enables non-parametric memory.

This article is part of the free-to-read Language AI Handbook

Choose your expertise level to adjust how many terms are explained. Beginners see more tooltips, experts see fewer to maintain reading flow. Hover over underlined terms for instant definitions.

RAG Motivation

Throughout this book, you've seen how language models have grown increasingly powerful. From the early n-gram models we explored in Part II to the transformer architectures of Parts X-XIII, and finally to the large-scale models like GPT-3 and LLaMA in Parts XVIII-XIX, each advancement has expanded what these systems can do. Models trained on trillions of tokens can now write essays, explain complex topics, and engage in nuanced conversations.

Yet despite these remarkable capabilities, large language models share a fundamental limitation: they can only know what they learned during training. Ask GPT-3 about events from 2023, and it draws a blank. Query a model about your company's internal documentation, and it can only guess. Push for precise technical specifications from a specialized domain, and you'll often receive confident-sounding but incorrect answers.

This chapter examines why these knowledge limitations exist, introduces the distinction between parametric and non-parametric knowledge systems, and motivates retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) as a powerful solution. Understanding these foundations will prepare you for the technical deep dives in subsequent chapters, where we'll explore RAG architecture, dense retrieval, and vector search mechanisms.

The Knowledge Problem in Language Models

Language models face several interrelated knowledge challenges that stem from how they store and access information. These aren't bugs to be fixed. They're inherent characteristics of the parametric approach to knowledge representation. To understand why RAG is effective, we must understand these limitations. They are not engineering failures but fundamental consequences of how neural networks encode information.

Knowledge Cutoff

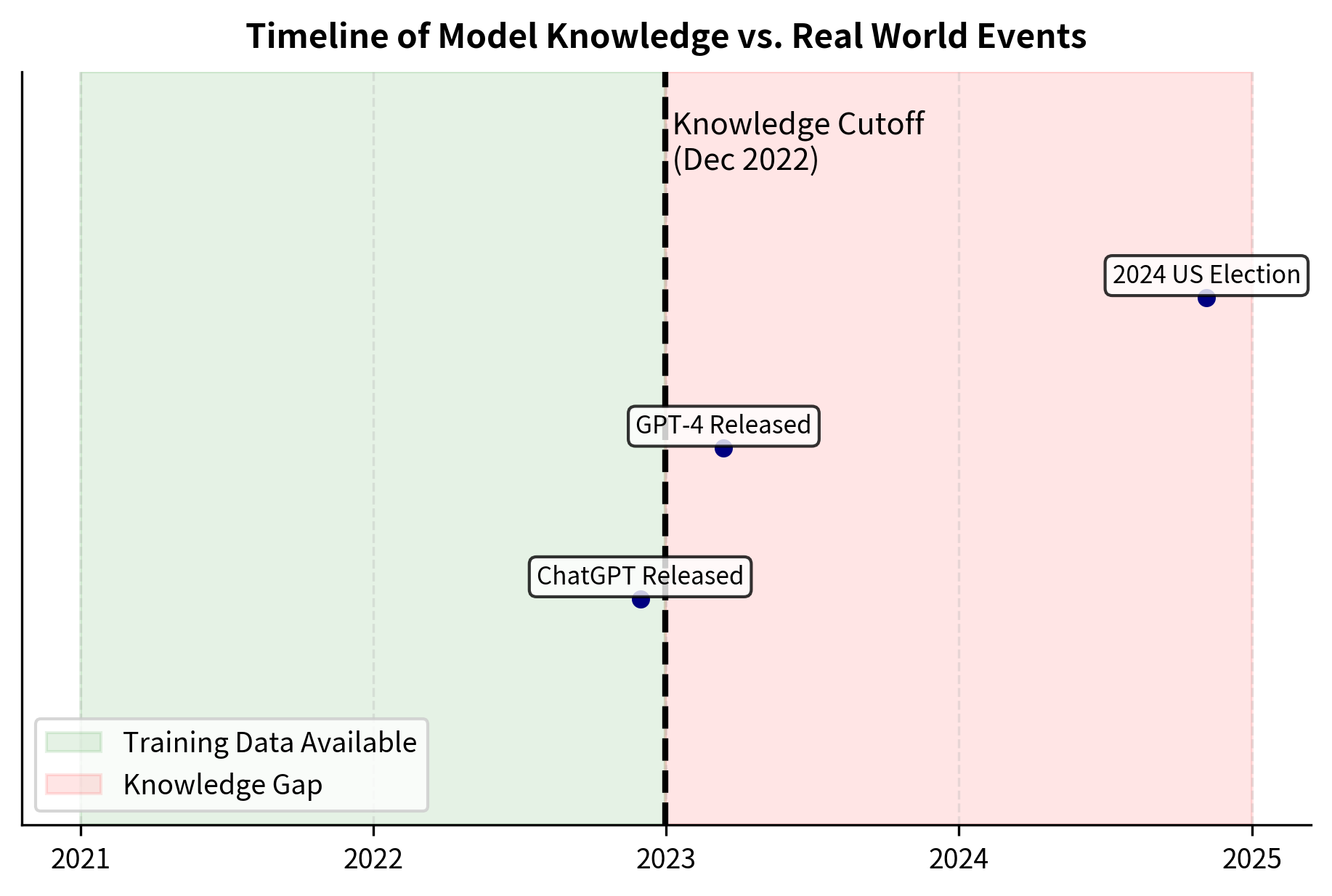

Every language model has a Knowledge cutoff date: the point at which its training data ends. Information about events, discoveries, or changes that occurred after this date simply doesn't exist in the model's parameters. This limitation emerges because neural networks only learn from the data they have seen. No architectural optimization can generate knowledge about events that occurred after the training data was assembled.

Consider a model trained on data through December 2022. It cannot know about:

- Scientific papers published in 2023

- Companies founded or acquired after its cutoff

- Changes to laws, regulations, or policies

- Updated product specifications or pricing

- Deaths, elections, or other current events

This isn't a matter of the model forgetting. The information was never there to begin with. The model's "knowledge" is a snapshot of the world at a particular moment, frozen in its parameters. Think of it like a photograph: no matter how high the resolution, a photograph taken in 2022 cannot show you what a building looked like after renovations completed in 2024. The limitation isn't in the quality of the camera but in the fundamental nature of what a photograph captures.

The output confirms that the model successfully retrieves information about events prior to its cutoff but fails to answer questions about 2023 and 2024. This binary behavior, knowing or not knowing based strictly on date, illustrates the rigid nature of parametric knowledge limits. There is no graceful degradation: the model either has access to information from its training window or it has nothing at all. The severity of this problem depends on the domain. For historical analysis or literary criticism, a knowledge cutoff may matter little. For financial services, medical advice, or news summarization, stale information can range from unhelpful to dangerous. A medical chatbot providing advice based on guidelines that were superseded two years ago could actively harm patients.

Hallucination and Factual Errors

As we discussed in the context of alignment in Part XXVII, language models are trained to generate plausible-sounding text, not necessarily accurate text. The training objective of next-token prediction rewards fluency and coherence; it does not directly penalize factual incorrectness. When a model doesn't know something, it doesn't say "I don't know": it generates text that fits the statistical patterns in its training data.

This leads to hallucination: the generation of factually incorrect but linguistically fluent content. The term "hallucination" is apt because, like a perceptual hallucination, the model perceives something that isn't there. It "sees" patterns and relationships that feel real and consistent with its internal representations but have no grounding in actual facts.

Understanding why hallucination occurs requires appreciating the probabilistic nature of language model generation. At each step, the model produces a probability distribution over possible next tokens. When the model is uncertain, perhaps because it's being asked about rare facts or topics barely represented in its training data, this distribution becomes flatter. Rather than strongly preferring one correct answer, the model assigns similar probabilities to many plausible-sounding options. It then samples from this distribution, potentially selecting tokens that form coherent sentences but express false information.

The examples above demonstrate how the model fabricates specific details, such as non-existent citations or population figures, with the same formatting as valid data. Notice how each hallucinated response follows the expected structure perfectly: the citation has author names, a year, a title, and a venue; the population figure is a specific number in a reasonable range; the theorem explanation begins with a formal statement. This structural correctness makes hallucination deceptive.

Hallucination is particularly problematic because it's often indistinguishable from accurate responses. The model uses the same confident, fluent language whether it's recalling genuine training data or fabricating details. You cannot easily tell which parts of a response to trust. A lawyer using a language model might receive a mix of real case citations and invented ones, with no indication of which is which. A student might learn "facts" that are entirely made up but presented with the same authoritative tone as accurate information.

Domain Knowledge Gaps

Training data for large language models skews heavily toward publicly available web text, books, and Wikipedia. This creates systematic gaps in domain-specific knowledge. The models develop broad but shallow knowledge across many topics, with depth concentrated in areas heavily represented online. Topics that are frequently discussed, well-documented, and publicly accessible receive dense coverage, while specialized, proprietary, or locally relevant information remains sparse or entirely absent.

The nature of these gaps reflects the distribution of internet content:

- Proprietary information: Internal company documentation, unpublished research, confidential processes

- Specialized domains: Niche technical fields with limited online presence

- Recent developments: Cutting-edge research not yet widely cited

- Local knowledge: Regional regulations, local business practices, cultural specifics

A model might excel at explaining general physics concepts while struggling with the specific calibration procedures for a particular laboratory instrument. It might discuss contract law in broad strokes but fail on jurisdiction-specific precedents. This pattern emerges because general physics appears in countless textbooks, educational websites, and discussion forums, while the calibration procedure for a specific instrument model might exist only in a proprietary manual that was never part of any training corpus.

These gaps matter enormously for practical applications. Enterprises don't typically need help with information that's already abundant online. They need assistance with their specific products, their particular processes, their unique organizational knowledge. The very information most valuable to organizations is precisely the information least likely to appear in language model training data.

The Retraining Problem

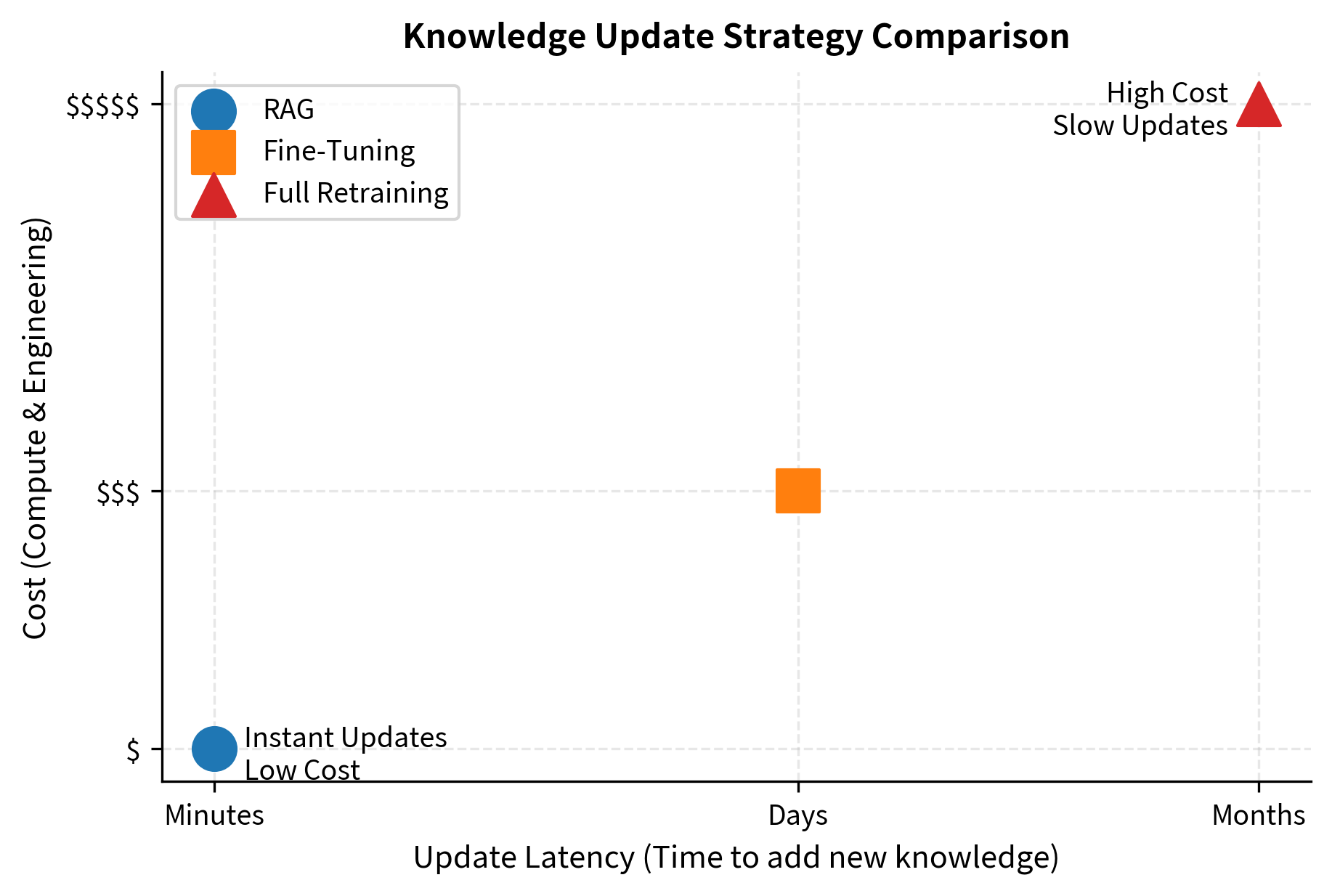

One apparent solution is retraining: update the model with new data to incorporate fresh knowledge. However, this approach faces significant practical barriers that make it unsuitable as a general solution to the knowledge problem.

Computational cost: Training large language models requires substantial compute resources. As we explored in Part XXI on scaling laws, training a model like LLaMA-70B requires thousands of GPU-hours. The compute costs scale with model size, and the largest models require tens of millions of dollars in compute for a single training run. Frequent retraining to stay current is economically impractical for most organizations. Even well-resourced technology companies typically retrain their flagship models at most a few times per year.

Catastrophic forgetting: As discussed in Part XXIV, neural networks can lose previously learned information when trained on new data. This phenomenon, known as catastrophic forgetting, means that simply adding new documents doesn't guarantee the model will retain its existing capabilities. Training on a corpus of medical literature might improve medical knowledge while degrading the model's ability to write poetry or solve math problems. Managing this tradeoff requires careful data mixing and training procedures that further increase cost and complexity.

Data quality control: Mixing new data into training requires careful curation. Low-quality or incorrect information can degrade model performance in unpredictable ways. A single batch of training data containing factual errors, biased content, or adversarial examples can propagate those issues throughout the model's responses. The curation effort required scales with the amount of new data, creating an ongoing operational burden.

Latency: Even with unlimited resources, retraining takes time. A model cannot instantly incorporate breaking news or real-time data. The pipeline from data collection through training, evaluation, and deployment typically spans weeks to months. For applications requiring current information, this latency is simply unacceptable.

Parametric vs Non-Parametric Knowledge

The knowledge limitations we've described arise from how language models store information. Understanding this storage mechanism, and its alternative, illuminates why retrieval-augmented generation works. This section develops the theoretical foundation for RAG by contrasting two fundamentally different approaches to representing knowledge in computational systems.

Parametric Knowledge

Parametric knowledge refers to information encoded directly in a model's learned parameters (weights). The model "remembers" facts by adjusting its weights during training such that these facts influence its outputs.

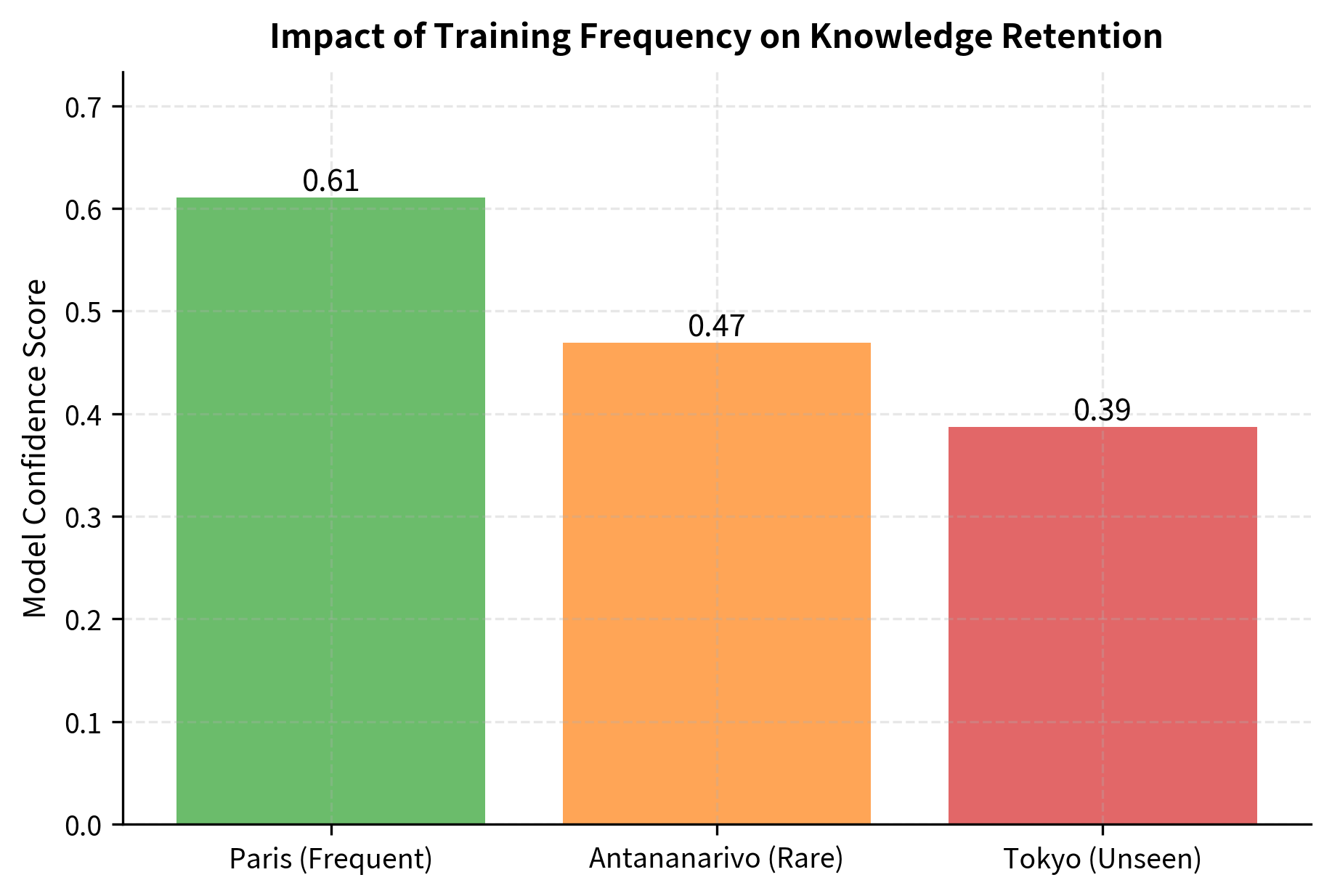

When you train a language model, knowledge gets compressed into the network's parameters. This compression is both the source of the model's power and the root of its limitations. A model with 70 billion parameters might train on 2 trillion tokens, meaning each parameter must somehow encode information from roughly 30 tokens on average. This compression is necessarily lossy. Not every detail survives, and which details are preserved depends on complex interactions between the training data, the learning algorithm, and the model architecture.

The process works roughly as follows: during training, the model sees "Paris is the capital of France" many times in various contexts. Through gradient descent, the weights adjust so that when given "The capital of France is," the model assigns high probability to "Paris." The fact isn't stored explicitly anywhere. It emerges from the collective influence of billions of parameters. In a sense, the model doesn't "know" that Paris is the capital of France in the way you know it. Rather, the model's parameters are configured such that this fact tends to surface when relevant.

This distributed representation has important implications that shape the behavior of parametric systems:

Implicit storage: You cannot point to specific weights and say "this is where the model knows that Paris is France's capital." The knowledge is distributed across the network in a holographic fashion. Each weight participates in encoding many facts, and each fact depends on many weights. This distributed representation is part of what enables generalization, but it also makes knowledge opaque and difficult to inspect or modify.

Compression artifacts: Rare facts, seen few times during training, get weaker encoding. Common facts dominate. This explains why models know Shakespeare's plays better than obscure regional poets. The training process essentially performs a kind of popularity-weighted memorization, where frequently encountered information receives more robust encoding. Facts that appeared only once or twice in training may be partially remembered, incorrectly remembered, or forgotten entirely.

Fixed capacity: The model has a fixed number of parameters. Once training ends, no new knowledge can enter without modifying weights through additional training. The model's knowledge capacity is determined at architecture design time, and no amount of clever prompting can teach the model facts it never learned. This constraint stands in stark contrast to human learning, where we can integrate new facts into our understanding almost instantly.

Interpolation over memorization: Models generalize from patterns rather than memorizing exact strings. When asked about a topic, the model doesn't retrieve a stored answer; it generates new text by interpolating between patterns seen during training. This enables creative responses but also enables hallucination. The model can generate plausible-sounding text about topics it has only glancing familiarity with, blending fragments of related knowledge in ways that may not reflect reality.

Frequently seen facts have stronger encoding than rare ones. Unseen facts produce unreliable, near-random responses because the model interpolates based on patterns rather than retrieving explicit records. This toy example illustrates a real phenomenon: language models exhibit clear frequency effects where common facts are more reliably recalled than rare ones, even when both appeared in training data.

Non-Parametric Knowledge

Non-parametric knowledge refers to information stored externally and retrieved at query time rather than encoded in model parameters. The "knowledge" exists in a separate data store that can be updated, extended, or modified without changing the model.

Non-parametric approaches take a fundamentally different stance on knowledge representation. Rather than compressing information into a fixed set of learned weights, these systems store facts explicitly in some form of external memory. At inference time, the system retrieves relevant information from this memory and uses it to inform its response. The term "non-parametric" reflects that the system's knowledge capacity isn't bounded by a fixed parameter count; it scales with the size of the external store.

Classic examples from earlier in this book include:

- TF-IDF retrieval (Part II): Documents stored as sparse vectors, retrieved by term overlap

- BM25 (Part II): Probabilistic retrieval based on term frequencies

- Dense retrieval: Documents stored as dense embeddings, retrieved by similarity (we'll explore this in upcoming chapters)

The key properties of non-parametric knowledge create a fundamentally different set of tradeoffs than parametric approaches:

Explicit storage: Each fact or document exists as a discrete item in the knowledge store. You can inspect, modify, or delete individual items. If you want to know whether a particular fact is in the system's knowledge, you can simply search for it. This transparency contrasts sharply with the inscrutability of parametric knowledge, where determining what a model "knows" requires empirical probing.

Unlimited capacity: Adding more storage doesn't require model changes. You can scale to billions of documents without retraining anything. The only constraints are storage costs and retrieval latency, both of which scale sub-linearly with modern indexing techniques. A system that starts with a thousand documents can grow to a billion documents without any architectural changes.

Instant updates: New information can be added immediately. A document uploaded at 2pm can be retrieved at 2:01pm. This immediacy enables real-time knowledge management that would be impossible with retraining-based approaches. Breaking news, newly published research, or freshly created internal documents become immediately available for retrieval.

Provenance: When you retrieve information, you know exactly where it came from. This enables citation and verification. You can trace any claim back to its source document, assess the credibility of that source, and verify the claim independently. This attribution capability is essential for applications where trust and accountability matter.

No compression loss: The original text is preserved exactly. There's no risk of facts being "forgotten" or distorted during encoding. A technical specification retrieved from a non-parametric store will contain exactly the precision and detail present in the original document, whereas the same information encoded parametrically might lose precision or introduce subtle errors.

This demonstrates key properties of non-parametric knowledge: documents are stored explicitly and can be inspected, additions are instant without training, and the source of every fact is known through its document identifier. Notice that the system returns the exact text that was stored, with no possibility of distortion or hallucination at the retrieval level. The retrieved documents provide a factual foundation that can then be processed by downstream systems.

The Complementary Relationship

Parametric and non-parametric approaches have complementary strengths and weaknesses. Neither approach dominates the other across all dimensions; instead, each excels in different aspects of the knowledge representation problem. Understanding these complementary properties reveals why hybrid systems offer such compelling advantages.

| Aspect | Parametric | Non-Parametric |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge update | Requires retraining | Instant addition |

| Storage efficiency | Highly compressed | Stores full documents |

| Generalization | Interpolates patterns | Returns exact matches |

| Capacity | Fixed at training | Scales with storage |

| Provenance | Opaque | Transparent |

| Rare facts | Often lost | Preserved exactly |

| Reasoning | Strong | Retrieval only |

The key insight behind RAG is that these approaches are not mutually exclusive. A system can use non-parametric retrieval to fetch relevant information and parametric generation to reason about and synthesize that information into a coherent response. This combination allows each component to do what it does best: the retrieval system provides precise, verifiable, updatable facts, while the language model contributes reasoning, synthesis, and fluent generation.

The division of labor addresses weaknesses on both sides. The retrieval component compensates for the language model's knowledge limitations, hallucination tendencies, and update difficulties. The language model compensates for the retrieval system's inability to reason, synthesize multiple sources, or generate coherent natural language responses. Together, they form a system more capable than either component alone.

Benefits of Retrieval-Augmented Generation

Retrieval-augmented generation combines the reasoning power of large language models with the precision and updatability of external knowledge stores. This hybrid approach addresses the knowledge limitations we've discussed while preserving the fluent generation capabilities that make LLMs useful. By understanding these benefits in detail, we can appreciate why RAG has become one of the most important techniques for deploying language models in production systems.

Access to Current Information

By retrieving from an external knowledge store, RAG systems can access information that post-dates the model's training cutoff. A model trained in 2022 can answer questions about 2024 events if those events exist in the retrieval corpus. This capability fundamentally changes the value proposition of language model deployments.

This decouples the model's capability from its knowledge. The same model weights can provide current answers indefinitely, as long as the retrieval corpus stays updated. This decoupling has profound practical implications: organizations can invest once in a capable base model and then maintain current information through simple document updates rather than expensive retraining cycles.

The retrieval corpus bridges the knowledge gap, allowing the model to answer questions about events that occurred after its training data cutoff. The model's reasoning capabilities, language understanding, and generation fluency remain exactly as they were at training time; only the factual grounding changes. This separation of concerns, distinguishing between capability and knowledge, is one of the most elegant aspects of the RAG architecture.

Reduced Hallucination Through Grounding

When a language model generates text purely from its parameters, it has no external check on factual accuracy. RAG provides grounding: the model generates responses based on retrieved documents rather than relying solely on compressed parametric memory. This grounding fundamentally changes the generation dynamics.

This reduces hallucination in several ways:

Evidence-based generation: The model can copy or paraphrase exact text from retrieved documents rather than reconstructing facts from imperfect memory. When the retrieval system returns a document stating "The melting point of iron is 1,538°C," the model can simply relay this fact rather than attempting to recall a number it may never have reliably encoded.

Explicit uncertainty: When no relevant documents are retrieved, the system can acknowledge uncertainty rather than fabricating answers. A well-designed RAG system can detect when retrieval returns low-confidence results and respond appropriately, saying something like "I couldn't find relevant information about that topic." This uncertainty signaling is difficult to achieve with pure parametric generation.

Constrained output space: The model focuses on information present in the context rather than freely generating from all possible continuations. The retrieved documents act as a kind of soft constraint, making the model much more likely to generate text consistent with those documents. This constraint reduces the probability of fabricating information that contradicts available evidence.

Grounding doesn't eliminate hallucination entirely. Models can still misinterpret retrieved text or fill gaps with fabricated details. A model might misread a number, draw incorrect inferences from correct facts, or hallucinate details to connect disparate pieces of retrieved information. However, empirical studies consistently show reduced factual errors in RAG systems compared to pure parametric generation. The improvement is particularly pronounced for specific factual claims, statistical figures, and technical details.

Domain Adaptation Without Retraining

Perhaps the most practically valuable benefit of RAG is enabling domain specialization without model modification. A general-purpose language model can become an expert in any domain simply by connecting it to domain-specific documents. This capability transforms the economics of domain-specific AI deployment.

Consider adapting a model for three different enterprise use cases:

Comparing these timelines to alternatives highlights the efficiency of RAG: fine-tuning requires weeks of data preparation, training, and evaluation, while retraining takes months and costs millions of dollars. RAG adaptation can often be completed in a single day, limited primarily by the time required to collect and index documents.

This flexibility is transformative for enterprise adoption. Organizations can deploy RAG systems using their proprietary data without sharing that data with model providers or undertaking expensive training projects. The proprietary documents never leave the organization's control; they're simply indexed locally and used to augment model responses. This addresses both practical cost concerns and data privacy requirements that often block AI adoption.

Transparency and Attributability

RAG systems can cite their sources. When the model generates a response, it can indicate which retrieved documents informed that response. This attribution capability addresses a critical gap in pure parametric systems, where the model cannot explain its knowledge origins.

The ability to cite sources enables several important capabilities:

Verification: You can check the original sources to verify claims. If the model states that a particular chemical has a specific hazard classification, you can examine the source document to confirm this classification, check for additional context, and assess whether the source is authoritative.

Trust calibration: You can assess source quality and adjust your trust accordingly. A response grounded in peer-reviewed medical literature deserves more confidence than one based on informal discussion forums. RAG allows you to make these distinctions.

Audit trails: Organizations can track how decisions were informed. In regulated industries, being able to demonstrate that automated systems base their outputs on approved documentation may be a compliance requirement. RAG systems naturally generate this documentation trail.

Debugging: When responses are wrong, you can diagnose whether the problem is retrieval (wrong documents) or generation (misinterpreting correct documents). This diagnostic capability dramatically simplifies the process of improving system performance over time.

This stands in stark contrast to pure parametric generation, where the model cannot explain why it believes something or where it "learned" a fact. The model's knowledge is distributed across billions of parameters in ways that resist human interpretation, making it impossible to trace specific outputs to specific training examples.

Cost Efficiency

Updating knowledge through RAG is dramatically cheaper than alternatives:

vs. Retraining: Training a large language model costs millions of dollars. Adding documents to a RAG index costs pennies per document. The cost difference is not marginal but rather spans several orders of magnitude. An organization might spend $10 million training a frontier model from scratch, or $10,000 retraining a smaller model, compared to perhaps $100 worth of compute to index a million documents for RAG.

vs. Fine-tuning: Even parameter-efficient fine-tuning requires GPU time, data preparation, and evaluation. RAG requires only document processing and indexing, which can run on standard CPU infrastructure. Additionally, fine-tuning creates model variants that must be maintained, versioned, and deployed, whereas RAG keeps a single model and updates only the document index.

vs. Larger models: One approach to reducing hallucination is using larger models with more parameters. RAG can achieve similar accuracy improvements at a fraction of the compute cost. A smaller model with RAG often outperforms a larger model without RAG on domain-specific tasks, while requiring less compute for both training and inference.

The cost advantage compounds with update frequency. A RAG system can incorporate new information daily or even hourly. Retraining can only happen at most quarterly for most organizations. This means RAG systems can stay orders of magnitude more current while spending orders of magnitude less on knowledge maintenance.

RAG Use Cases

The benefits we've described make RAG particularly valuable for certain application categories. Understanding these use cases helps clarify where RAG adds the most value.

Enterprise Knowledge Management

Large organizations accumulate vast stores of internal documentation: policies, procedures, technical specifications, project reports, meeting notes, and institutional knowledge that exists nowhere else.

RAG enables "chatting with your documents": employees can ask natural language questions and receive answers grounded in company-specific information:

- "What is our vacation policy for employees in Germany?"

- "How did we resolve the authentication issue in the Q3 release?"

- "What safety certifications does our new manufacturing process require?"

These questions have precise answers that exist in company documents, but finding them traditionally requires knowing which document to look in. RAG transforms document retrieval from keyword search to semantic question answering.

Customer Support

Support teams handle questions that often have documented answers but require navigating complex product documentation, FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and past ticket resolutions.

RAG-powered support systems can:

- Provide instant, accurate responses to common questions

- Ground answers in official documentation rather than model improvisation

- Assist human agents by surfacing relevant knowledge base articles

- Scale support capacity without proportional staffing increases

The grounding aspect is crucial here. Hallucinated technical advice could damage customer relationships or even cause harm.

Research and Analysis

You might need to synthesize information from large document collections: scientific literature, patent databases, legal archives, financial filings.

RAG supports your research workflows by:

- Answering questions across document collections too large for any human to read

- Identifying relevant sources that might otherwise be missed

- Summarizing findings with citations to original sources

- Comparing information across multiple documents

The attribution capability is essential for research applications where claims must be traceable to evidence.

Regulatory Compliance

Compliance teams must answer questions about evolving regulations that span thousands of pages of legal text, agency guidance, and internal policies.

RAG helps compliance by:

- Providing instant access to relevant regulatory language

- Tracking how policies apply to specific scenarios

- Identifying potential conflicts between regulations

- Maintaining audit trails of what information informed decisions

The ability to update the knowledge base as regulations change, without retraining, makes RAG particularly suited to this domain.

Code Assistance

Software development involves constant reference to documentation, API specifications, code examples, and internal coding standards.

RAG-powered coding assistants can:

- Answer questions about specific libraries or frameworks

- Retrieve relevant code examples from internal repositories

- Surface documentation for unfamiliar APIs

- Apply organization-specific coding standards

The combination of general coding capability (from the language model) with specific documentation (from retrieval) creates more useful assistance than either component alone.

Limitations and Design Considerations

While RAG addresses many limitations of pure parametric systems, it introduces its own challenges that practitioners must understand.

Retrieval Quality as a Bottleneck

RAG systems are only as good as their retrieval. If the retriever fails to find relevant documents, the generator cannot produce correct answers, no matter how capable the underlying language model. This "garbage in, garbage out" dynamic means that retrieval quality often matters more than generation quality.

Poor retrieval can manifest in several ways. The retriever might return documents that are topically related but don't contain the answer. It might miss relevant documents due to vocabulary mismatch between the query and the document text. For ambiguous queries, it might retrieve documents about the wrong interpretation. These failure modes are fundamentally different from hallucination. The model isn't making things up; it simply never received the relevant information.

This has significant implications for system design. Investment in retrieval quality, including embedding models, indexing strategies, and query processing, often yields higher returns than upgrading the language model. We'll explore dense retrieval, hybrid search, and other techniques for improving retrieval quality in upcoming chapters.

Latency Overhead

RAG introduces additional latency compared to pure generation. The system must encode the query, search the index, retrieve documents, and incorporate them into the prompt before generation can begin. For real-time applications, this overhead can be significant.

The latency breaks down into several components: embedding the query (typically 10-50ms), vector search (10-100ms depending on index size and type), fetching document content (varies with storage), and the increased generation time due to longer context. For interactive applications, the total added latency of 100-500ms may noticeably impact user experience.

Various optimization strategies can mitigate this: caching frequent queries, pre-computing embeddings, using approximate nearest neighbor algorithms, and streaming generation while retrieval completes in parallel.

Context Window Constraints

As we discussed in Part XV on context length challenges, language models have finite context windows. Retrieved documents compete for context space with your query, system prompts, and previous conversation history.

This creates a retrieval budget problem: retrieving more documents provides more information but leaves less room for generation and may introduce noise. Retrieving fewer documents risks missing relevant information. Finding the right balance requires tuning to specific use cases.

Document chunking strategies, which we'll cover in Part XXIX Chapter 5, help manage this constraint. By breaking documents into smaller, focused chunks, systems can pack more relevant information into the available context.

Maintaining the Knowledge Base

Unlike pure parametric systems where knowledge is fixed at training, RAG systems require ongoing knowledge base maintenance. Documents must be added, updated, and removed. Indexes must be rebuilt or updated. Quality control must ensure documents are accurate and relevant.

This operational burden is often underestimated. A RAG system isn't "done" at deployment. It requires continuous investment to remain useful.

Summary

This chapter has examined why large language models, despite their remarkable capabilities, face fundamental knowledge limitations. These limitations stem from the parametric nature of neural networks: knowledge compressed into fixed weights at training time cannot be updated without retraining, cannot scale beyond the model's capacity, and cannot be traced to specific sources.

The key concepts we've explored include:

- Knowledge cutoff: Models only know what existed in their training data, creating an information gap that grows over time

- Hallucination: Without external grounding, models generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect content

- Parametric vs non-parametric knowledge: Parametric knowledge is compressed into model weights; non-parametric knowledge is stored externally and retrieved at query time

- Complementary strengths: Parametric approaches excel at reasoning and generalization; non-parametric approaches excel at precision and updatability

Retrieval-augmented generation combines these approaches, using retrieval to provide relevant information and generation to synthesize coherent responses. The benefits include access to current information, reduced hallucination through grounding, domain adaptation without retraining, transparency through attribution, and dramatically lower costs for knowledge updates.

RAG has found applications across enterprise knowledge management, customer support, research, compliance, and software development. These are domains where accurate, traceable, and updatable knowledge is essential.

The next chapter introduces the RAG architecture in detail, showing how retrieval and generation components connect to create a unified system. Subsequent chapters will dive into the technical components: dense retrieval, embedding models, vector similarity search, and indexing strategies that make efficient retrieval possible at scale.

Quiz

Ready to test your understanding? Take this quick quiz to reinforce what you've learned about the motivation for Retrieval-Augmented Generation.

Comments